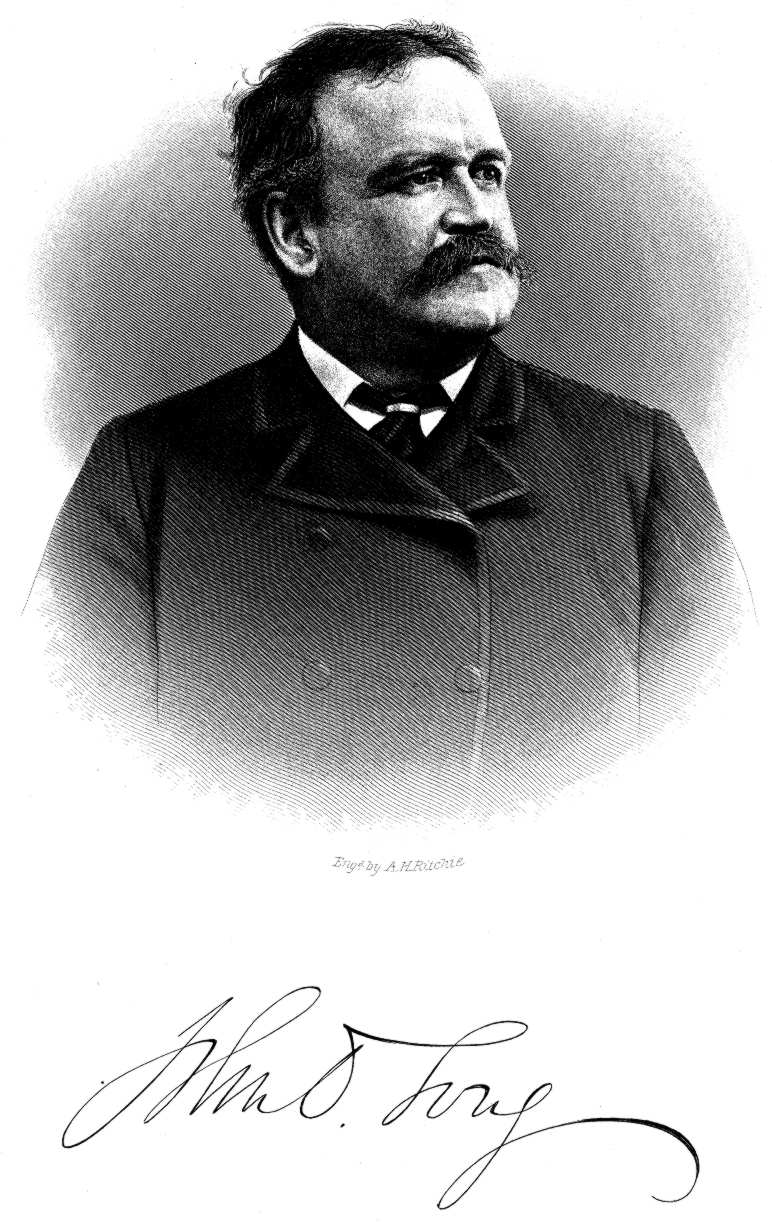

John D. Long

Project Gutenberg's The Bay State Monthly, Volume 3, No. 4, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Bay State Monthly, Volume 3, No. 4 Author: Various Release Date: February 9, 2006 [EBook #17724] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BAY STATE MONTHLY *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, David Garcia and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections)

Hon. John D. Long, the thirty-second governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, under the Constitution, and whose wise, prudent administration reflected great credit upon himself, was born in Buckfield, Maine, October 27, 1838.

His father was a man of some prominence in the Pine Tree State, and in the year in which his more distinguished son first saw the light, he ran for Congress on the Whig ticket, and although receiving a plurality of the votes cast, he was defeated.

The son was a studious lad, more fond of his books than of play, and thought more of obtaining a solid education than of developing his muscles as an athlete. At the proper age he entered the academy at Hebron, the principal of which was at that time Mark H. Dunnell, subsequently a member of Congress from Minnesota.

At the age of fourteen, young Long entered the Freshman class at Harvard College. He at once took high rank, stood fourth in his class for the course, and second at the end of the Senior year. He was the author of the class ode, sung on Commencement day.

After leaving College, Mr. Long was engaged as principal of the Westford Academy, an old institution incorporated in 1793. He remained at Westford two years, highly esteemed by his pupils and beloved of the whole people. As a teacher, he won marked success, and many of his contemporaries regret that he did not always remain in the profession. But he cherished another, if not a higher ambition. From Westford he passed to the Harvard Law School, and to the offices of Sidney Bartlett and Peleg W. Chandler, in Boston. In 1861, he was admitted to the bar, and then he opened an office in his native town, to practise his new profession.

He soon found, however, that Buckfield was not the place for him. People there were far too honest and peace-loving, and minded their own business too well to assist in building up a lawyer's reputation. After a two years' stay, therefore, he removed to Boston, and entered the office of Stillman B. Allen, where he rapidly gained an extensive practice. The firm, which consisted of Mr. Allen, Mr. Long, Thomas Savage and Alfred Hemenway, had their offices on Court Street, in an old building now on the site of the new Young's Hotel. Mr. Long remained in the firm until his election, in November, 1879, to the governorship of Massachusetts.

In 1870, he was married to Miss Mary W. Glover of Hingham, Massachusetts, to which town he had previously removed his residence. During his executive administration, he had the great misfortune to undergo bereavement by the loss of this most estimable lady, whose wise counsel often lent him encouragement in the perplexed days of his official life.

In 1875, Mr. Long was chosen to represent the Republicans of the second Plymouth District in the legislature. He at once took a prominent position, and gained great popularity with his fellow members. In 1876, he was re-elected to the House, and soon after he was chosen speaker. This position he filled with dignity, grace, and with an ease surpassed by no speaker before him or since. He showed himself thoroughly versed in parliamentary practice, and his tact was indeed something remarkable. So great was his popularity that, in 1877, he had every vote which was cast for speaker, and in the following year every vote but six.

In the fall of 1877, the Republican State Convention assembled at Worcester, and it at once became apparent that many of the delegates were desirous to vote for Mr. Speaker Long for the highest office in the Commonwealth. At the convention he received, however, only 217 votes for candidate; and his name was then withdrawn. At the convention of 1878, he again found numerous supporters, and received 266 votes for Governor. He was then nominated for Lieutenant Governor by a very large majority, and was elected. In the convention of 1879, Governor Thomas Talbot declining a re-nomination, Lieutenant Governor Long received 669 votes to 505 votes for the Hon. Henry L. Pierce, and was nominated and elected, having 122,751 votes to 109,149 for General Benjamin F. Butler, 9,989 for John Quincy Adams, and 1,635 for the Rev D.C. Eddy, D.D.

On the fifteenth of September, 1880, Governor Long was re-nominated by acclamation, and in November he was re-elected by a plurality of about 52,000 votes,—the largest plurality given for any candidate for the governorship of Massachusetts since the presidential year of 1872. He continued to hold the office, by re-election until January, 1883.

Several important acts were passed during the administration of Governor Long, and notably among these was an act fixing the penalties for drunkeness,—an act providing that no person who has been served in the United State army or navy, and has been honorably discharged from the service, if otherwise qualified to vote, shall be debarred from voting on account of his being a pauper, or, if a pauper, because of the non-payment of a poll tax,—an act which obviated many [223] of the evils of double taxation by providing that, when any person has an interest in taxable real estate as holders of a mortgage, given to secure the payment of a loan, the amount of which is fixed and stated, the amount of said person's interest as mortgagee shall be assessed as real estate in the city or town where the land lies, and the mortgagor shall be assessed only for the value of said real estate, less the mortgagee's interest in it.

The creditable manner in which Mr. Long conducted the affairs of the State induced his constituents to send him as their representative in Washington. He was elected a member of the Forty-eighth Congress, and is now a member also of the Forty-ninth. His record thus far has been altogether honorable and characterized by a sturdy watchfulness of the interests entrusted to his care.

As a man of letters. Governor Long has achieved a reputation. Some years ago, he produced a scholarly translation, in blank verse, of Virgil's Æneid, which was published in 1879 in Boston. It has found many admirers among students of classical literature. Governor Long, amid busy professional and official duties, has also written several poems and essays which reflect credit upon his heart and brain. His inaugural addresses were masterpieces of literary art, and the same can be said of his speeches on the floor of Congress, all of them, polished, forceful and to the point.

Mr. Long is a very fluent speaker, and, without oratorical display, he always succeeds in winning the attention of his auditors. It is what he says, more than how he says it, that has won for him his great popularity on the platform. When, in February last, the Washington monument was dedicated, he it was that was chosen to read the magnificent oration of Robert C. Winthrop.

As a specimen of Mr. Long's happy way of expressing timely thoughts, the following passage, selected from an address which he delivered at Tremont Temple, Boston, on Memorial Day, 1881, deserves to be read:—

"Scarce a town is there—from Boston, with its magnificent column crowned with the statue of America at the dedication of which even the conquered Southron came to pay honor, to the humblest stone in rural villages—in which these monuments do not rise summer and winter, in snow and sun, day and night, to tell how universal was the response of Massachusetts to the call of the patriots' duty, whether it rang above the city's din or broke the quiet of the farm. On city square and village green stand the graceful figures of student, clerk, mechanic, farmer, in that endeared and never-to-be-forgotten war-uniform of the soldier or the sailor, their stern young faces to the front, still on guard, watching the work they wrought in the flesh, and teaching in eloquent silence the lesson of the citizen's duty to the state, How our children will study these! How they will search and read their names! How quaint and antique to them will seem their arms and costume! How they will gather and store up in their minds the fine, insensibly filtering percolation of the sentiment of valor, of loyalty, of fight for right, of resistance against wrong, just as we inherited all this from the Revolutionary era, so that, when some crisis shall in the future come to them, as it came to us, they will spring to the rescue, as sprang our youth, in the beauty and chivalry of the consciousness of a noble descent."

On a pleasant June morning after a long drive through shady country lanes, the little pile of rocks was reached, which for two hundred and fifty years has marked the western corner of the lot, six miles square, granted to form the plantation at Musketaquid on the second of September 1635. Resting here in the shadow of the pines, listening to the busy gossip of the squirrels, many scenes and people which have made the town of Concord, Massachusetts, so noted, seemed to pass in review, some of which will here be recounted.

Perhaps on this spot Simon Willard and his associates may have stood, and these rough rocks been laid in place by their hands. Peter Bulkeley, the wise and reverend, may have consecrated this solemn occasion with prayer in accordance with the good old custom of the time. To the two gentlemen above-mentioned the chief credit of the settlement of Concord is mainly due. Attention was early called to the broad meadows of the Musketaquid or 'grass grown river' and a company marched from the ancient Newtown to form a settlement there early in the fall of 1635. Few of the thousand pilgrims who arrive every year over the Fitchburg and Lowell railroads can imagine the discomforts of the toilsome journey of these early settlers as they penetrated through the unbroken wilderness and wet and dreary swamps, devoting nearly two weeks to the journey now easily accomplished in forty minutes. Many of their cattle died from exposure and change of climate, and great heroism and courage were required to make them persevere. They were kindly received by the Indians who were in possession of the lands along the rivers, and who finally consented to part with them so peacefully, that the name of the town was called Concord.

Near the present site of the hotel stood an oak tree under which tradition locates the scene of these amicable bargains. On a hill at the junction of the Sudbury and Assabet rivers, rumor also locates the lodge of the squaw who reigned as queen over one of the Indian tribes, and thus introduced into the village female supremacy which has steadily gained in power ever since. Later the Apostle Eliot preached here often, and converted many dusky followers into "Praying Indians." Remnants of their lodge-stones, arrow-heads and other relics were abundant half a century ago in the great fields and other well known resorts, and a large kitchen-miden or pile of shells, now fast becoming sand, marks the place of one of their solemn feasts. The early explorers seem to have built at first under the shelter of the low sand-hills which extend through the centre of the town, and perhaps some of them were content to winter in caves dug in the western slopes. Their first care was for their church which was organized under the Rev. Peter Bulkeley and John Jones as pastor and teacher, but after a few years Mr. Jones left for Connecticut with one-third of his flock. Many other [225] things occurred to discourage this little band, but their indomitable leader was not one to abandon any enterprise. Rev. Peter Bulkeley was a gentleman of learning, wealth and culture, as was also Simon Willard who managed the temporal affairs of the plantation. It is a curious commentary on the present temperance question to learn from early records that to the chief men alone was given the right to sell intoxicating liquors. In many of the early plantations the land seems to have been divided into parcels, which were in some cases distributed by lot, and this fact may perhaps have originated the word lot as applied to land. A large tract near the centre of the town was long held in common by forty associates, the entrance to which was behind the site of the former Courthouse, now occupied by the Insurance Office. Before many years had passed this little town lost in some degree its peaceful reputation, and became a centre of operations during King Philip's war, many bodies of armed men being sent out against the savages, and one to the relief of Brookfield, under Mr. Willard. Block houses were built at several exposed points, the sites of which, with other noted places will soon be marked with memorial tablets.

Trained by this Indian warfare, the inhabitants of Concord were prepared for the events which were to follow, and when, in 1775, their town furnished the first battle-field of the American Revolution, they were able to offer "the first effectual resistance to British aggression." In the old church built in 1712 was held the famous Continental Congress where the fiery speeches of Adams and Hancock did so much to hasten the opening of the inevitable conflict between England and her provinces. The same frame which was used for the present building echoed with the stirring words of the patriots as well as with the fearless utterances of the Rev. William Emerson, who, on the Sunday before Concord fight, preached his famous sermon on the text "Resistance to tyrants is obedience to God." The events which preceded the Revolution need not be recorded here, nor any facts not intimately connected with the history of the town, which had been quietly making preparations for the grand event. Under Colonel James Barrett and Major Buttrick, the militia and other soldiers were drilled and organized, some of whom under the name of Minute-men were ordered to be ready to parade at a moment's notice. Cannon and other munitions of war were procured, which with flour and provisions were secreted in various places.

Tidings of these preparations was carried to the British in Boston by the spies and tories who abounded in the town, and on the evening of the eighteenth of April, an expedition consisting of about eight hundred men was sent out to counteract them. Paul Revere having been stopped at Lexington, was able to spread the news of the attack by means of Dr. Prescott who had been sitting up late with the lady whom he afterwards married. Love overleaps all obstacles, and with cut bridle-rein the Doctor leaped his gallant steed over walls and fences and reached Concord very early in the morning. At the ringing of the bell the Minute-men flocked to their standard on the crest of Burying Hill where they were joined by Rev. William Emerson, whose marble tomb stands near the very spot, and also marks the place where Pitcairn and Smith controlled the operations of the British during the forenoon.

The Liberty-pole occupied the next eminence, a few rods farther east. Here the little band of patriots awaited the coming of the well-disciplined foe, ignorant that their country-men had fallen on Lexington Common before the very muskets that now glittered in the morning sun. Some proposed to go and meet the British, and some to die holding their ground; but their wiser commanders led them to Ponkawtassett Hill a mile away, where the worn and weary troops were cheered by food and rest, and were reinforced by new arrivals from Acton and other towns, until they numbered nearly three hundred men. After destroying many stores in the village, and sending three companies to Colonel Barrett's in vain search for the cannon, which were buried in the furrows of a ploughed field, a detachment of British soldiers took possession of the South Bridge, and three companies were left to guard the old North Bridge under command of Captain Lawrie.

Seeing this manoeuvre the Americans slowly advanced and took up their position on the hill at the west of the bridge which the British now began to destroy. Colonel Isaac Davis of Acton now offered to lead the attack, saying, "I have not a man who is afraid to go," and he was given the place in front of the advancing column, and fell at the first volley from the British, who were posted on the other bank of the river. Major Buttrick then ordered his troops to fire, and dashed on to the bridge, driving the enemy back to the main road, down which they soon retreated to the Common, to join the Grenadiers and Marines who there awaited them. The Minute-men crossed over the hills and fields to Merriam's corner when they again attacked the British, who were marching back to Boston, and killed and wounded several of the enemy without injury to themselves. Meanwhile the three companies had returned from Colonel Barrett's and marched safely over the bridge which had been abandoned by both sides, and joined the main force of the British who had waited for them on the Common.

After the skirmish at Merriam's corner, the fighting was continued in true Indian fashion from behind walls and buildings with such effect that the British [227] would have been captured had they not been re-enforced at Lexington by a large force with field pieces.

In 1836, the spot on which the British stood was marked by a plain monument, and in 1875 the place near which Captain Isaac Davis and his companions fell was made forever memorable by the noble bronze statue of the Minute-man by Daniel Chester French in which the artist has carefully copied every detail of dress and implement, from the ancient firelock, to the old plough on which he leans.

In order to prove her claim to the peaceful name of Concord, this village seems to have taken an active part in every warlike enterprise which followed. Several of her men fought at Bunker Hill and one was killed there. In Shay's Rebellion Job Shattuck of Groton attempted to prevent the court, which assembled in Concord, from transacting its business, by an armed force. In the war of 1812, Concord men served well, and in the old anti-slavery days many a fierce battle of tongue and pen was waged by the early supporters of the then unpopular cause. John Brown spent his fifty-eighth birthday in the town the week before he left for Harper's Ferry, and the gallows from which his "soul went marching on." The United States officials who came to arrest Mr. Sanborn for his knowledge of Brown's movements were advised by the women and men of Concord to retreat down the old Boston road a la British; and when the call came for troops to put down the late Rebellion, Concord was among the first to [228] send her militia to the field under the gallant young farmer-soldier, Colonel Prescott, who at Petersburg,

"Showed how a soldier ought to fight,

And a Christian ought to die."

In memory of the brave who found in Concord "a birthplace, home or grave" the plain shaft in the public square was erected on the spot where the Minute-men were probably first drawn up on the morning of the nineteenth of April. 1775 to listen to the inspiring words of their young preacher, Rev. William Emerson, and ninety years after in the same place his grandson R.W. Emerson recounted the noble deeds of the men who had gallantly proved themselves worthy to bear the names made famous by their ancestors at Concord fight. The Rev. William Emerson in 1775 occupied and owned The Old Manse, which was built for him about ten years before, on the occasion of his marriage to Miss. Phoebe Bliss, the daughter of one of the early ministers of Concord. Mr. Emerson was so patriotic and eager to attack the invaders at once, that he was compelled by his people to remain in his house, from which he is said to have watched the battle at the bridge from a window commanding the field. He soon after joined the army as chaplain and died the next year at Rutland, and his widow married some years after the Rev. Dr. Ripley who succeeded him in his church and home, and lived until his death in the Manse which has always remained in the possession of his descendants. Dr. Ripley ruled the church and town with the iron sway of an old-fashioned New England minister, and the old Manse has for years been a literary centre. In the old dining room, the solemn conclave of clergymen have cracked many a hard doctrine and many a merry jest, seated in the high-backed leather chairs which have stood for one hundred and twenty years around the old table. Here Mrs. Sarah Ripley fitted many a noted scholar for college in the intervals of her housekeeping labors [229] before the open kitchen fireplace. In an attic room, called the Saint's chamber, from the penciled names of honored occupants, Emerson is said to have written Nature, and perhaps other works, as much of his time was spent in the Manse at various periods of his life. Here Hawthorne came on his wedding tour and lived for two happy years and wrote the Mosses from an Old Manse and other works. In his study over the dining-room, his name is written with a diamond on one of the little window panes, and with the same instrument his wife has recorded on the dining-room window annals of her daughter who was born in the house.

On the hill opposite, the solitary poplar, the last of a group set out by some school-girls eighty years ago, still stands. Each of its companions died about the time of the decease of its lady planter, and as the one who set out the present tree has lately died, the poplar suffered last year from a stroke of lightning which may cause it to follow soon.

Nearly opposite the Manse on the road toward the village is the well preserved house, formerly the home of Elisha Jones, which bears in the L the mark of a bullet fired into it on the day of Concord fight. On the same side of the way a little farther down is a house, a portion of which was built by Humphrey Barrett as early as 1640. As the route of the retreating British from the bridge is followed for half a mile down this road the common is reached, which is bounded on the Northern end by the stores, from which the British took flour and other Continental supplies, and at the opposite end stands Wright tavern which the gallant Pitcairn immortalized by stirring his brandy with a bloody finger, unconscious that the rebel blood he promised to stir would cause his own to flow at Bunker Hill.

Opposite Wright tavern is one of the oldest burying hills in the country, on which may be seen the stone of Joseph Merriam, who died in 1677 and those of Colonel Barrett who commanded the troops, and of Major Buttrick who led them at the bridge, and of his son the fifer who furnished the music to which they marched. Here also is the inscription to John Jack famous for its alliteration, and the tablets of the old ministers and founders of church and State. Some of these headstones bear coats of arms and rough portraits in stone, while others more symbolic, are content with the winged cherubim or solemn weeping willow, and others older still preserve the antique coffin shape. About one [230] quarter of a mile in the rear of this historic Burying Hill is Sleepy Hollow, the cemetery now so famous, which will be for centuries as now, the Mecca of pious pilgrims, for here Emerson sleeps beneath the giant pine of which he loved to write and which in grateful recognition ever whispers its solemn dirge over the dead poet, who will live forever in his writings. His grave is now marked by a rough rock of beautiful pink crystal-quartz, and his son Waldo lies close beside him, with no monument but the imperishable one of Threnody. Mrs. Ruth Emerson, the mother of the poet and his brothers, nephews and grandchildren rest near him, and close by is the grave of Miss Mary Moody Emerson, the eccentric genius whom he well appreciated.

Ridge Path leads up the steep hill past the grave of Emerson and also to most of the noted burial places. On ascending this path at the western end, Hawthorne's lot is first reached, surrounded by a low hedge of Arbor Vitae and the grave of the great writer is marked only by two low white stones one of which bears his name. At his head lies his little grandson, Francis Lathrop, and by his side Julian's little daughter Gladys. Behind is the grave of Thoreau, a plain brown stone, and very near are the graves of two of the little women, Amy and Beth, by the side of their noble mother, Mrs. Alcott. Colonel Prescott and many noted citizens are buried on this path which has for a chief ornament the handsome monument of the Honorable William Whiting, nearly opposite which is the Manse lot, with its memorials to Mrs. Ripley and her sons. On the side of this hill is the Monument to Honorable Samuel Hoar which bears upon its upper [231] portion an appropriate motto from Pilgrim's Progress, and an oft-quoted inscription which with the one in the same lot to his daughter, is recommended to all lovers of pure English as they are true records of the pure souls they commemorate.

Returning from the cemetery to the square, we still follow the British down the Boston road and pass at the corner near the church another building from which stores were taken and on the left houses of historical fame, the house and shop of Captain Brown who led the second company in the fight, the home of the patriot Lee and John Beatton who left funds for church purposes. Below this house which is two hundred years old, a guard was posted on the day of the fight and before it stand two elms so old that they are filled with bricks inside, and mended outside with plaster in order to preserve them. The next house on the right is the home of Emerson, a plain wooden building with trees near the western side, and a fine old-fashioned garden in the rear. His study was in the front of the house at the right of the entrance. One side is filled to the ceiling with books, and a picture of the Fates hangs above the grate, a table occupies the centre, at the right of which is the rocking chair in which he often sat, and his writing implements lie near on the table. From the study two doors lead to the long parlor with its large fire-place around which so many noted people have gathered.

After passing the home of Emerson the road turns toward the left and leads past the farm and greenhouses of John B. Morse, the agricultural author, to the School of Philosophy which has just completed its seventh session with success, the attendance having steadily improved certainly as far as culture is considered. It stands in the grounds of the Orchard House now the home of Dr. Harris who has carried out the idea of Mr. Alcott of whom he bought the place, by laying out beautiful walks over the crest of the wooded hill. He has surrounded a tall pine on the hill top with a strong staircase by which it can easily be climbed to a height of 54 feet from the base and 110 feet from the road in front of the school building or chapel. Orchard House was for years the home of the Alcott family [232] where Louisa wrote and May painted and their father studied philosophy. A broken rustic fence one of the last traces of Mr. Alcott's mechanical skill forms the slight barrier between the grounds at the Orchard House and Wayside, which Mr. Alcott bought in 1845 and a few years later sold to Nathaniel Hawthorne who owned it at the time of his death. The house is a strange mixture of the old and new, as the rear part bears evident traces of antiquity, at the right were the Hawthorne parlors and reception rooms, at the left of the entry his library, sometimes called the den, and in front a small room with a low window separates the dining room from the reception room and the whole is crowned with a tower built by Mr. Hawthorne for a study where he found the quiet and seclusion which he loved. Much of Mr. Hawthorne's composition seems to have been done as he wandered up and down the shady paths which wind in every direction along the terraced hillside, and a small crooked path is still shown as the one worn by the restless step of genius. Mr. G.P. Lathrop who married Rose Hawthorne sold the place to Daniel Lothrop, the Boston publisher, who has thoroughly repaired it and greatly added to its beauty by reverently preserving every landmark in his improvements, and now in summer his accomplished wife, known to the public by her nom de plume of Margaret Sidney, entertains many noted people at Wayside. On the Boston road and a little farther on is the garden of Ephraim Bull, the originator of the Concord grape and below is Merriam's Corner to which the Minute-men crossed and attacked the British as above mentioned. Half a mile across country lies Sandy Pond from which the town has its water supply which can furnish daily half a million gallons of pure water, each containing only one and three-fourths grains of solid matter. From Sandy Pond several narrow wood-roads lead to Walden, a mile distant where Thoreau lived for eight months at an expense of one dollar and nine cents a month. His house cost thirty dollars and was built by his own hands with a little help in raising and in it he wrote Walden, considered by many his best book. Mr. Thoreau died in May 1862, in the house occupied by the Alcott family on Main street where many of the principal inhabitants live. At the junction of this street with Sudbury street stands the Concord Free Public Library, the generous gift of William Munroe, Esq. which was dedicated October 1, 1873, and now owns nearly twenty thousand volumes and numerous works of art, coins and relics, the germs of a gallery which will be added in future. Behind the many fine estates which front on Main street, Sudbury river forms another highway and many boats lie along the green lawns ready to convey their owners up river to Fairhaven bay, Martha's Point, the Cliffs and Baker Farm, the haunts of the botanists, fishermen and authors of Concord, or down to Egg Rock where the South Branch unites with the lovely Assabet to form the Concord River which leads to the Merrimac by way of Bedford, Billerica and Lowell. But most of the boats go up the Assabet to the beautiful bend where the gaunt hemlocks lean over to see their reflection in the amber stream, past the willows by which kindly hands have hidden the railroad, to the shaded aisles of the vine-entangled maples where the rowers moor their boats and climb Lee Hill which Mr. C.H. Hood has so beautifully laid out.

After the October elections, in the autumn of 1860, had been carried by the Republicans, the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, in November, became a foregone conclusion. On the 5th day of October,—the initial day of the American Rebellion,—Governor Gist, of South Carolina, wrote a confidential circular-letter, which he despatched by special messenger to the governors of the so-called Cotton States. In this letter he requested an "interchange of opinions which he might be at liberty to submit to a consultation of the leading men" of his State. He added that South Carolina would unquestionably call a convention as soon as it was ascertained that a majority of Lincoln electors were chosen in the then pending presidential election. "If a single State secedes," he wrote, "she will follow her. If no other State takes the lead, South Carolina will secede; in my opinion, alone, if she has any assurance that she will be soon followed by another or other States; otherwise, it is doubtful." He asked information, and advised concerted action.

The governors of North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Georgia sent replies; but the discouraging tone of their responses establishes, beyond controversy, that, with the exception of South Carolina, "the Rebellion was not in any sense a popular revolution, but was a conspiracy among the prominent local office-holders and politicians, which the people neither expected nor desired, and which they were made eventually to justify and uphold by the usual arts and expedients of conspiracy."

From the dawn of its existence the South had practically controlled the government; she very naturally wished to perpetuate her control. The extension of slavery and the creation of additional slave States was a necessary step in the scheme, and became the well-defined single issue in the presidential election, though not necessarily the primal cause of the impending civil war. For the first time in the history of the republic the ambition of the South met overwhelming defeat. In legal form and by constitutional majorities Abraham Lincoln was chosen to the presidency, and this choice meant, finally, that slavery should not be extended.

An election was held in South Carolina in the month of October, 1860, under the manipulation of the conspirators. To a Legislature chosen from the proper material, Governor Gist, on November 5th, sent a message declaring "our institutions" in danger from the "fixed majorities" of the North, and recommending the calling of a State Convention, and the purchase of arms and the material of war. This was the first official notice and proclamation of insurrection.

The morning of November 7th decided the result of the national election. From this time onward everything was adroitly managed to swell the revolutionary furor. The people of South Carolina, and especially of Charleston, indulged in a continuous holiday, amid unflagging excitement, and, while singing the Marseillaise, prepared for war! Everybody appeared to be satisfied,—the conspirators, because their schemes were progressing, and the people, because, innocently duped, they hoped for success.

The first half of the month of December had worn away. A new governor, Francis W. Pickens, ruled the destinies of South Carolina. A Convention, authorized by the Legislature, met at Columbia, the capital of the State, and, on the 20th of December, passed unanimously what it called an ordinance of secession, in the following words:—

We, the people of the State of South Carolina, in convention assembled, do declare and ordain, and it is hereby declared and ordained, that the ordinance adopted by us in convention on the 23d day of May, in the year of our Lord 1788, whereby the Constitution of the United States of America was ratified, and also all Acts and parts of Acts of the General Assembly of this State ratifying amendments of the said Constitution, are hereby repealed; and that the Union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved.

The ordinance was immediately made known by huge placards, issued from the Charleston printing-offices, and by the firing of guns, the ringing of bells, and other jubilations. The same evening South Carolina was proclaimed an "independent commonwealth." Said one of the chief actors: "The secession of South Carolina is not an event of a day. It is not anything produced by Mr. Lincoln's election, or by the non-execution of the Fugitive-Slave Law. It is a matter which has been gathering head for thirty years." This was a distinct affirmation, which is corroborated by other and abundant testimony, that the revolt was not only against right, but that it was utterly without cause.

The events which took place in South Carolina were, in substance, duplicated in her sister States of the South. Mississippi seceded on January 9, 1861; Florida, on January 10; Alabama, on January 11; Georgia, on January 18; Louisiana, on January 26; and Texas, on February 1; but not a single State, except Texas, dared to submit its ordinance of secession to a direct vote of the people.

One of the most striking features in the early history of the secession is the apparent delusion in the minds of the leaders that secession could not result in war. Even after the firing upon Sumter, the delusion continued to exist. Misled, perhaps, by the opinion of ex-President Pierce,1 the South believed that the North would be divided; that it would not fight. It is but fair to say that the tone of a portion of the Northern press, and the speeches [235] of some of the Northern Democrats, and the ambiguous way of speaking on the part of some of the Northern Republicans rather warranted than discouraged such an opinion.

There was, however, one prominent man from Massachusetts, who had united with the Southern leaders in the support of Breckenridge, who had wisdom as well as wit, and who now sought to dispel this false idea. In the month of December he was in Washington, and he asked his old associates what it meant.

"It means," said they, "separation, and a Southern Confederacy. We will have our independence, and establish a Southern government, with no discordant elements."

"Are you prepared for war?" inquired Butler.

"Oh! there will be no war; the North will not fight."

"The North will fight. The North will send the last man and expend the last dollar to maintain the government."

"But," said his Southern friends, "the North can't fight; we have too many allies there."

"You have friends," said Butler, "in the North, who will stand by you so long as you fight your battles in the Union; but the moment you fire on the flag the Northern people will be a unit against you. And you may be assured, if war comes, slavery ends."

Butler was far too sagacious a man not to perceive that war was inevitable, and too sturdy and patriotic not to resist it. With a boldness and frankness which have shown themselves through his whole political career, he went to Buchanan; he advised and begged him to arrest the commissioners, with whom he was then parleying, and to have them tried for treason! Such advice it was as characteristic of Benjamin F. Butler to give as it was of President Buchanan to disregard.

But the adoption of secession ordinances and the assumption of independent authority was not enough for the Cotton Republic. Though they hoped to evade civil war, still they never forgot for a moment that a conflict was not only possible, but even probable. Their prudence told them that they ought to prepare for such an emergency by at once taking possession of all the arms and military forts within their borders.

At this time there was a large navy-yard at Pensacola, Florida; from twelve to fifteen harbor forts along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts; half-a-dozen arsenals, stocked with an aggregate of one hundred and fifty thousand arms (transferred there about a year before from Northern arsenals, by Secretary Floyd); three mints; four important custom-houses; three revenue cutters, on duty at leading Southern seaports, and a vast amount of valuable miscellaneous property,—all of which had been purchased with the money of the Federal Government.

The land on which the navy-yards, arsenals, forts, and, indeed, all the [236] buildings so purchased and controlled, stood, was vested in the United States, not alone by the right of eminent domain, but also by formal legislative deeds of cession from the States themselves, wherein they were located. The self-constituted governments of these State now assumed either that the right of eminent domain reverted to them, or that it had always belonged to them; and that they were perfectly justified in taking absolute possession, "holding themselves responsible in money damages to be settled by negotiation." The Federal Government and the sentiment of the North regarded this hypothesis false and absurd.

In due season the governors of the Cotton States, by official orders to their extemporized militia companies, took forcible possession of all the property belonging to the Federal Government lying within the borders of these States. This proceeding was no other than levying actual war against the United States. There was as yet no bloodshed, however, and for this reason: the regular army of the United States amounted then to but little over seventeen thousand men, and, most of these being on the Western frontier, there was only a small garrison at each of the Southern forts; all that was necessary, therefore, was for a superior armed force—as a rule, State militia—to demand the surrender of these forts in the name of the State, and it would at once, though under protest, be complied with. There were three notable exceptions to this peaceable evacuation,—first, no attempt was made against Fort Taylor, at Key West; Fort Jefferson, on Tortugas Island; and Fort Pickens, at Pensacola, on account of the distance and danger; second, part of the troops in Texas were eventually refused the promised transit, and were captured; third, the forts in Charleston harbor underwent peculiar vicissitudes, which will be recounted later on.

The conspiracy which, for a while at least, seemed destined to overcome all obstacles, was not confined to South Carolina or the Cotton States. Unfortunately it had established itself in the highest official circles of the National Government. Three members of President Buchanan's cabinet—Cobb, of Georgia, Secretary of the Treasury; Floyd, of Virginia, Secretary of War; and Thompson, of Mississippi, Secretary of the Interior—were rank and ardent disunionists. To the artful machinations of these three arch-traitors, who cared more for self than they did for the South, the success of the conspiracy was largely due. Grouped about them was a number of lesser functionaries, willing to lend their help. Even the President did not escape the suspicion of the taint of disloyal purpose.

The first and chief solicitude of the disunionists of South Carolina was to gain possession of the forts. A secret caucus was held. "We must have the forts," was its watchword; and, ere long, from every street corner in Charleston came the impatient echo: "The forts must be ours."

To revert to the beginning. On the 1st of October, 1860, the Chief of Ordnance wrote to Secretary Floyd, urging the importance of protecting the ordnance and ammunition stored in Fort Sumter, Charleston harbor, providing it met the approval of the commanding officer of Fort Moultrie. The Secretary had no objections; but the commanding officer of Fort Moultrie, [237] while giving a very hesitating approval of the application, expressed "grave doubts of the loyalty and reliability of the workmen engaged on the fort," and closed his letter (dated November 8th) by recommending that the garrison of Fort Moultrie should be reinforced, and that both Fort Sumter and Castle Pinckney should be garrisoned by companies sent at once from Fortress Monroe, at old Point Comfort. A few days later he ordered the ordnance officer at the Charleston office to turn over to him, for removal to Fort Moultrie, all the small arms and ammunition which he had in store. The attempt to make this transfer was successfully resisted by the Charleston mob.

This evidence of loyalty on the part of the commanding officer of the troops in Charleston harbor was not appreciated at Washington. His removal was promptly ordered by the Secretary of War. The officer thus summarily dealt with was Lieutenant-Colonel J.C. Gardner, First Artillery, U.S.A., a native of Massachusetts, and an old veteran of the war of 1812. Thus, so far as history reveals, was a son of the old Bay State the first to resist the encroachments of the Southern conspiracy. It is worthy of note, also, that the removal of Col. Gardner was in a measure due to the recommendation of Major (afterwards General) Fitz John Porter.

Major Robert Anderson was ordered, on November 15th, to take command of Fort Moultrie. He was chosen probably in the belief that, being a Southern man, he would eventually throw his fortunes with the South. On the 21st of November Major Anderson arrived at the fort, and on the 23d of the same month he wrote to Secretary Floyd as follows:—

Fort Sumter and Castle Pinckney must be garrisoned immediately if the government determines to keep command of the harbor.2

In the same letter he also expressed the opinion that the people of South Carolina intended to seize all the forts in Charleston harbor by force of arms as soon as their ordinance of secession was published.

The faith of Secretary Floyd must, indeed, have been shaken while reading such words! He might have ordered the removal of the writer of them had not a rather unexpected incident now occurred to divert his attention.

The Secretary of State, the venerable Lewis Cass of Michigan, at once denounced submission to the conspiracy as treasonable, and insisted that Major Anderson's demand for reinforcements should be granted. This episode was a political bomb-shell in the camp of the enemy. The President became a trifle alarmed, and sent for Floyd. A conference between the President and the Secretary was held, when the latter "pooh-poohed" the actual danger. "The South Carolinians," said he, "are honorable gentlemen. They would scorn to take the forts. They must not be Irritated." But the President evinced restlessness; he may have suspected the motive of his cabinet officer. Floyd, too, grew restless; the obstinacy of the executive [238] alarmed him. He was only too glad to consent to the suggestion that General Scott should be consulted.

General Scott rose from his sick-bed in New York, and hastened to Washington, on the 12th of December. On the 13th he had an interview with the President, in which he urged that three hundred men be sent to reinforce Major Anderson at Fort Moultrie. The President declined, on the ground, first, that Major Anderson was fully instructed what to do in case he should at any time see good reason to believe that there was any purpose to dispossess him of any of the forts; and, secondly, that at this time (December 13th) he—the President—believed that Anderson was in no danger of attack.

The President acted his own will in the matter. On the 15th General Cass tendered his resignation, and retired from official life, for the avowed reason that the President had refused to reinforce Anderson, and was negotiating with open and avowed traitors. Secretary Cobb had resigned a few days before. Black, the Attorney-General, was now made Secretary of State; Thomas, of Maryland, Secretary of the Treasury; and Edwin M. Stanton was appointed Attorney-General. The President believed, and undoubtedly honestly, that, by his concession to Floyd and the other conspirators, he had stayed the tide of disunion in the South. It now appears how quickly and unexpectedly he was undeceived. While these events were transpiring, a paper addressed "To our Constituents," and urging "the organization of a Southern Confederacy," was being circulated for signature through the two houses of Congress. It was signed by about one-half of the Senators and Representatives of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas, and bore the date, "Washington, December 15, 1860." It is to be remembered as the official beginning of the subsequent Confederate States, just as Governor Gist's October circular was the official beginning of South Carolina secession and rebellion.

On the 20th of December, South Carolina, as has been previously stated, passed its ordinance. The desire, several times already expressed, to hold possession of the forts in Charleston harbor now took the form of a demand. The State Convention appointed three Commissioners to proceed to Washington to "treat for the delivery of the forts, magazines, light-houses, and other real estate, for an apportionment of the public debt, for a division of all other property, and generally to negotiate about other measures and arrangements." The Commissioners arrived in Washington on the 26th of December, and, by special appointment, were to meet the President at one o'clock on the following day. Before that hour arrived an unlooked-for event occurred.

We must now turn back again. Major Anderson, it will be remembered, had been sent to Charleston by order of Lieutenant-General Scott, acting, of course, under orders of the Secretary of War. Major Anderson's [239] first letter, dated November 23d, was sent through the regular channels. It appears from the records3 that, on the 28th of November, he was ordered by Secretary Floyd to address all future communications only to the Adjutant-General or direct to the Secretary of War. From this time forth, then, Major Anderson could communicate only with the conspirators against his government.

At last General Scott began to wonder why he had received no further tidings from Major Anderson, and on the 27th of December he delivered the following message to the President:—

Since the formal order, unaccompanied by special instructions, assigning Major Anderson to the command of Fort Moultrie, no order, intimation, suggestion, or communication for his government and guidance, has gone to that officer, or any of his subordinates, from the head-quarters of the army; nor have any reports or communications been addressed to the General-in-chief from Fort Moultrie later than a letter written by Major Anderson, almost immediately after his arrival in Charleston harbor, reporting the then state of the work.

This letter reached the President on the 27th. On the day before Major Anderson had transferred his entire garrison from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter. It was a bold move, done without orders, and solely because there was no longer hope that the President would send reinforcements. It was a judicious move, because Sumter was the real key to Charleston harbor. It was an act of patriotism which will forever enshrine the name of Anderson in American history.

The tidings reached Washington. Disappointed and chagrined, Secretary Floyd sent the following telegram:—

WAR DEPARTMENT.

ADJUTANT-GENERAL'S OFFICE, December 27, 1880.

MAJOR ANDERSON, Fort Moultrie:—

Intelligence has reached here this morning that you have abandoned Fort Moultrie, spiked your guns, burned the carriages, and gone to Fort Sumter. It is not believed, because there is no order for any such movement. Explain the meaning of this report.

J.B. FLOYD,

Secretary of War.

The answer was as follows:—

CHARLESTON, December 27, 1860.

HON. J.B. FLOYD, Secretary of War:—

The telegram is correct. I abandoned Fort Moultrie because I was certain that, if attacked, my men must have been sacrificed, and the command of the harbor lost. I spiked the guns, and destroyed the carriages, to keep the guns from being used against us.

If attacked, the garrison would never have surrendered without a fight.

ROBERT ANDERSON,

Major First Artillery.

The event reached the President's ears; he was perplexed, and postponed the promised interview with the Commissioners one day. He met them on the 28th. He states, in his Defence, published in 1866, that he informed them at once that he "could recognize them only as private gentlemen, and not as commissioners from a sovereign State; that it was to Congress, and to Congress alone, they must appeal." Nevertheless, he expressed his willingness to communicate to that body, as the only competent tribunal, any proposition they might have to offer; as if he did not realize that this proposal was a quasi-recognition of South Carolina's claim to independence, and a misdemeanor meriting impeachment.

The Commissioners, strange to say, were either too stupid or too timid to perceive the advantage of this concession. Fortunately for the country, their indifference lost to Rebellion its only possible chance of peaceful success.

The Commissioners evidently believed that the President was within the control of the cabinet cabal, for they made an angry complaint against Anderson, and imperiously demanded "explanations." For two days the President wavered. An outside complication tended to open his eyes. On the 31st of December Floyd resigned the portfolio of war; and, on the same day, the President sent to the Commissioners a definite answer that, "whatever might have been his first inclination, the Governor of South Carolina had, since Anderson's movement, forcibly seized Fort Moultrie, Castle Pinckney, and the Charleston arsenal, custom-house, and post-office, and covered them with the palmetto flag; that under such circumstances he could not, and would not, withdraw the Federal troops from Sumter." The angry Commissioners returned home, leaving behind them an insolent rejoinder, charging the President "with tacit consent to the scheme of peaceable secession!"

The crisis of December 31st changed the attitude of the Government toward Rebellion. Joseph Holt, of Kentucky, was appointed Secretary of War. General Scott was placed in military control.

An effort was at once made to reinforce Sumter. On the 5th of January notice was sent by Assistant Adjutant-General Thomas, from New York, to Major Anderson that a swift steamship, "Star of the West," loaded with two hundred and fifty recruits and all needed supplies, had sailed, that same day, for his relief. Major Anderson failed to receive the notice. On the morning of the 9th the steamer steamed up the channel in the direction of Sumter, when presently she was fired upon vigorously by the secessionists. Her captain ran up the stars and stripes, but quickly lost heart as he caught sight of the ready guns of Fort Moultrie, then put about, and back to sea.

The commander at Sumter was enraged. He sat down and wrote a brief note to the Governor of South Carolina, demanding to know "if the firing on the vessel and the flag had been by his orders, and declaring, unless the act were disclaimed, he would close the harbor with the guns of Sumter." [241] The Governor's reply was both an avowal and a justification of the act. Anderson, in a second note, stated that he would ask his government for instructions, and requested "safe conduct for a bearer of despatches." The Governor, in reply, sent a formal demand for the surrender of the fort. Anderson responded to this, that he could not comply; but that, if the government saw fit "to refer this matter to Washington," he would depute an officer to accompany the messenger.

This meant a truce, which the conspirators heartily welcomed. On the 12th of January, therefore, Attorney-General I.W. Hayne, of South Carolina, proceeded to Washington as an envoy to carry to President Buchanan the Governor's demand for the surrender of Fort Sumter. The matter was prolonged; but, on the 6th of February, Mr. Hayne found that his mission was a failure.

On the 4th of February, while the Peace Conference, so called, met in Washington to consider propositions of compromise and concession, the delegates of the seceding States assembled in Montgomery, Alabama, to organize their conspiracy into an avowed and opened rebellion. On the 9th Jefferson Davis, of Mississippi, was elected President, and Alexander H. Stephens, of Georgia, Vice-President of the new Confederacy. On the 18th Davis was inaugurated.

On the 1st of March General Beauregard was, by the rebel government, placed in command of the defence of Charleston harbor, with orders to complete preparations for the capture of Fort Sumter. The Governor had been exceedingly anxious that the capture should be attempted before the 4th of March. "Mr. Buchanan cannot resist," he wrote to Davis, "because he has not the power. Mr. Lincoln may not attack, because the cause of quarrel will have been, or may be considered by him, as past."

President Lincoln was inaugurated on the 4th of March, 1861. With an unanswerable argument against disunion, and an earnest appeal to reason and lawful remedy, he closed his inaugural address with the following impressive declaration of peace and good-will:—

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war.

The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors; you can have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one,—to preserve, protect, and defend it.

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break, our bond of affection.

The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone all over this broad land, will yet swell the Chorus of the Union when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

On the 15th of March President Lincoln, having been advised by General Scott that it was now "practically impossible to relieve or reinforce Sumter," propounded the following question to his cabinet: "Assuming it to be possible [242] to provision Sumter, is it wise, under all the circumstances of the case, to attempt to do so?" Five of the seven members of the cabinet argued against the policy of relief. On the 29th the matter came up again, and four of the seven then favored an attempt to relieve Major Anderson. The President at once ordered the preparation of an expedition. Three ships of war, with a transport and three swift steam tugs, a supply of open boats, provisions far six months, and two hundred recruits, were fitted out at New York, and, with all possible secrecy, sailed on the 9th and 10th of April, "under sealed orders to rendezvous before Charleston harbor at daylight on the morning of the 11th."

Meanwhile preparations for the capture of Sumter had been steadily going on under the direction of General Beauregard, one of the most skilful of engineers. On the 1st of April he telegraphed to Montgomery, the capital of the new confederacy:—

Batteries ready to open Wednesday or Thursday. What instructions?

On the same day orders were issued to stop all courtesies to the garrison, to prohibit all supplies from the city, and to allow no one to depart from the fort. On the 7th Anderson received a confidential letter, under date of April 4th, from President Lincoln, notifying him that a relief expedition would be sent, and requesting him to hold out, if possible, until its arrival.

On the morning of the 8th the following communication from the President was, by special messenger, placed in the hands of Governor Pickens:—

I am directed by the President of the United States to notify you to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in provisions, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, or in case of an attack upon the fort.

This message was at once communicated to Jefferson Davis, at Montgomery, who entertained the opinion that the war should be begun without further delay. On the 10th Beauregard was instructed to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter, and to reduce it in case of refusal.

On the following day, at two o'clock in the afternoon, General Beauregard sent two of his aids to make the demand; but it was refused. Still another message was sent, with the same result. On the morning of the 12th, at twenty minutes past three o'clock, General Beauregard sent notice to Anderson that he would open fire upon Sumter in one hour from that time.

At half-past four appeared "the first flash from the mortar battery near old Fort Jackson, on the south side of the harbor, and an instant after a bombshell rose in a slow, high curve through the air, and fell upon the fort."

It was the first gun in the Rebellion. Gun after gun responded to the signal, and through thirty-six hours, without the loss of a single life in the besieged garrison. At noon, on Sunday, the 14th of April, Major Anderson hauled down the flag of the United States, and evacuated Fort Sumter. Before sunset the flag of the Confederate States floated over the ramparts.

The following telegrams were transmitted:—

STEAMSHIP "BALTIC," OFF SANDY HOOK,

April 18 (1861), 10.30 A.M., via New York.

Having defended Fort Sumter for thirty-four hours, until the quarters were entirely burned, the main gates destroyed by fire, the gorge walls seriously injured, the magazine surrounded by flames, and its door closed from the effect of heat, four barrels and three cartridges of powder only being available, and no provisions remaining but pork, I accepted terms of evacuation offered by General Beauregard, being the same offered by him on the 11th inst., prior to the commencement of hostilities, and marched out of the fort Sunday afternoon, the 14th inst., with colors flying and drums beating, bringing away company and private property, and saluting my flag with fifty guns.

ROBERT ANDERSON,

Major First Artillery, Commanding.

HON. S. CAMERON, Secretary of War, Washington.

WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, April 20, 1861.

MAJOR ROBERT ANDERSON, Late Commander at Fort Sumter:—

MY DEAR SIR,—I am directed by the President of the United States to communicate to you, and through you to the officers and men of your command at Forts Moultrie and Sumter, the approbation of the government of your and their judicious and gallant conduct there, and to tender you and them the thanks of the government for the same.

SIMON CAMERON,

Secretary of War.

The conspiracy had now ceased to be such. Revolution and war had begun, and by the firing upon Fort Sumter the political atmosphere was cleared up as if by magic. If there were now any doubters on either side they had betaken themselves out of sight; for them, and for all the world, the roar of Beauregard's guns had changed incredulity into fact. Behind those guns stood seven seceded States, with the machinery of a perfectly organized local government and with a zeal worthy of a nobler cause.

The news of the assault reached the Capitol on Saturday, April 13th, On Sunday, the 14th, the President and his cabinet held their first council of war. On the following morning the first "call for troops" was proclaimed to the whole country, in a grand "appeal to all loyal citizens to favor, facilitate, and aid this effort to maintain the honor, the integrity, and existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular government."

The North was now aroused. Within forty-eight hours from the publication of the proclamation armed companies of volunteers were moving towards the expected scene of conflict. For the first time in the history of this nation parties vanished from politics, and "universal opinion recognized but two rallying points,—the camps of the South which gathered to assail the Union, and the armies of the North that rose to defend it."

The watchword of the impending conflict was sounded by Stephen A. Douglas, one of the most powerful and energetic of public leaders, a recent [244] candidate for the presidency, and the life-long political antagonist of Abraham Lincoln. On Sunday, the 14th of April, while the ink was scarcely yet dry upon the written parchment of the proclamation, Mr. Douglas called at the White House, and, in a long interview, assured his old antagonist of his readiness to join him in unrelenting warfare against Rebellion. Shortly afterwards he departed for his home in Illinois, where, until his death, which occurred a few weeks later, he declared, with masterly eloquence, that,—

"Every man must be for the United States or against it; there can be no neutrals in this war—only patriots and traitors."

"Hurrah! the drums are beating; the fife is calling shrill;

Ten thousand starry banners flame on town, and bay, and hill;

The thunders of the rising wave drown Labor's peaceful hum;

Thank God that we have lived to see the saffron morning come!

The morning of the battle-call, to every soldier dear,—

O joy! the cry is "Forward!" O joy! the foe is near!

For all the crafty men of peace have failed to purge the land;

Hurrah! the ranks of battle close; God takes his cause in hand!"

1 (return)

"If, through the madness of Northern abolitionists, that

dire calamity (disruption of the Union) must come, the fighting will not

be along Mason and Dixon's line merely. It will be within our own

borders, in our own streets, between the two classes of citizens to

whom I have referred. Those who defy law, and scout constitutional

obligation, will, if we ever reach the arbitrament of arms, find

occupation enough at home."—Letter to Jefferson Davis, dated

January 6, 1860.

2 (return)

The word "must" is italicized in the original letter. See

Official Records of the Rebellion, Vol. I., p. 76.

3 (return)

See Official Records of the Rebellion, I., p. 77.

Tommy Taft, or T.T. as he was wont to call himself, had always regretted two misfortunes,—first, the indisputable fact of his birth, and second, the imprisonment of his father, not long afterwards.

The earlier misfortune, Tommy Taft, not being at the time aware of it, was of course quite unable to prevent. The later misfortune it was alike beyond his power to forestall. It came to pass that young Tommy Taft grew up to be as crude a specimen of body and soul as had ever flourished in Boston-town.

I have not set myself the task of following the drift of his life from the dawn of babyhood to the twentieth anniversary of the same. But one event ought to be here recalled, which was, that on a certain day Tommy Taft was at work in a garden and in just that part of the garden, it ought to be said, where the wall was so low that a person could easily look over it into the long, narrow road.

Tommy Taft was not particularly fond of work; in other words, he was not a great worker. On this occasion, however, the promise of an extra shilling being uppermost in his mind, he plied his energies with more than wonted skill. He [245] was disposed to be meditative as well, and so deeply that he chanced not to perceive an aged personage who, for perhaps five and twenty minutes, had been cautiously scrutinizing him from across the wall.

It was a most extraordinary fit of sneezing—nothing more nor less—that first attracted the attention of Tommy Taft, and prompted him to look up. And what did he see? Only a weather-beaten face, shaded by a ragged straw hat out of which peeped locks of grizzled gray hair. The owner leaned somewhat heavily against the wall.

Tommy Taft was not amazed; but if he had not already become accustomed to affronts and ill-shapen visages, he might have been awed into silence. He merely paused, with his right foot on the shoulder of the spade share, and peered at the stranger. To the best of his knowledge, he had never seen him before. On a former time, however, he had chanced to see his own face in a mirror and, odd as it may seem, he now remarked to himself a striking resemblance between the two faces,—his own and that of the new comer. But his thoughts were quickly turned.

"I say, young man!"

"What say?" replied Tommy Taft.

"You don't happen to know a young man by the name o' Tom Taft, do you?"

"I reckon I do." The youth plunged the spade share into the earth, and folded his arms.

"Have a shake, then," continued the stranger.

"But that ain't a tellin' me who you be," said Tommy Taft, approaching and holding out his hand.

"I'm Jim Taft; and if so be your father was a shoemaker in this town and got locked up—I say, I'm he!"

There was pathos in the utterance of these words, and, somehow or other, Tommy Taft's heart fluttered just a little and before he was aware of it a tear was trickling down his cheek.

"Are you happy, young man," queried the elder. He drew himself up on the wall.

"Well, I s'pose I am, though I ain't got nuthin'. But folks as haint got nuthin' and enjoy it is a plagued sight richer than sich as has got everything and don't enjoy it. Yes—I s'pose I'm happy."

"And where's the old woman?"

"Dead, I s'pose."

"Dead!"

"Or in the work-house where she might'nt have been, if you'd a stayed round."

Jim Taft, for it was he, began to think, and the longer he thought, the more troubled he looked.

"You won't say as you saw me loafin' around here, will you?" he asked at length; "that is, if you won't give me a lift, me—your father?"

"How a lift?" inquired his interlocutor.

"A few shillings perhaps; or, perhaps you ain't got a pair o' boots as has in 'em more leather 'n holes, or a pair of breeches as is good for suthin'."

"Wait a bit!" said Tommy Taft. He disappeared; but he soon came back, with an old pair of boots in one hand and a pair of pantaloons in the other.

"There's suthin' in the nigh pocket," he remarked, as he handed the pantaloons to his parent. "I've often s'posed you'd come back, and would need the money what I saved for you."

The parent, however, had not the courtesy to return thanks. He was more anxious to know something about Tom's employer and his whereabouts.

"He's a good one, he is," said Tommy Taft; "and no, he ain't to home. He's in ——; and I've got to meet him to-night in the tavern there—."

"In Hog's Lane?"

"Yes."

"Hylton has a heap o' money, Tommy."

"If he have or no, I don't reckon its none o' your business, or mine nuther."

The parent noticed the surly tone in which his son had just spoken, and concluded to say "good day," and to be off.

Tommy Taft wondered what could be the cause of so sudden a departure; and then he wondered whether, it really was his father that had so unexpectedly accosted him. He went back to his spade, and next wondered whether the man might not be an escaped convict. If so, how came he to know John Hylton?

In obedience to orders, Tommy Taft set off to meet his employer at the tavern in Hog's Lane. He supped that evening with the keeper. Afterwards, he lighted his pipe, drew a chair up to the open fireplace, and smoked in silence. Still later, he betook himself through a long, narrow entry, up a narrow flight of stairs, and into a small, square room. After he had closed the door behind him, he observed another door, which, he concluded, opened into the next apartment. It was locked. Tommy Taft was to pass the night in this self-same room, and he had good reasons for believing that his employer occupied the room adjoining and was already sound asleep.

The hours sped by. The tavern-keeper looked up to the clock,—it was after midnight. He locked the big door, and had just diminished the number of burning lamps from six to two, when he heard the sound of voices as in dispute, and seemingly issuing from the room just above. He hurried to the foot of the stairs, and listened. He distinctly caught the voice of Mr. Hylton, and the words of another voice,—"You'll be sorry for that!" The tavern-keeper heard nothing more. Presently, he too went to bed.

Morning came, and the servants were busy in the kitchen. At half-past six, Tommy Taft ought, as on former occasions, to have carried a pitcher of hot water up to his employer's bedroom. But he failed to do so, this morning. At seven, Mr. Hylton ought to have been seated at the breakfast table; but he did not appear.

The tavern-keeper, when the clock had struck eight, went upstairs. He rapped on the door of the small square room. No response. He forced open the door.

"Ah!" he exclaimed. "Tommy Taft gone! and the bed not slept in, neither!"

The window was open. It had rained during the night, and on the soft, gravel mould beneath the window he discovered foot prints. He turned, and went to the door which communicated between the two apartments. It was unlocked. He turned the knob,—opened the door gently, and beheld John Hylton lying in a pool of blood, with his throat gashed, and with a large clasp-knife clenched in his right hand!

It was indeed a mystery. The discovery of the tragedy was followed by intense excitement. The coroner's jury suspected Tommy Taft as the murderer, because the knife which was found in the hand of the victim bore on its hilt the initials "T.T.", and because the tavern-keeper testified that he had heard angry words in the night.

Tommy Taft was brought to trial. It was proved that the murdered man's money-bag was rifled of all coin, but of only one bank note,—and that, the one which the tavern-keeper had had in his possession the afternoon before the tragedy and which Tommy Taft got changed on the day after the murder. These facts, together with the footprints on the gravel soil, enabled the prosecuting attorney to make out what seemed to both judge and jury a very strong case. Indeed, there was but one person in the court room that believed the prisoner innocent,—that was Tommy Taft himself.

He admitted that he had had a dispute with his employer, but gave no cause and that the latter had peremptorily dismissed him from further service; that the bank-note was given to him that very same night, as the full amount due him; that after the dispute, he could not go to bed; that he bethought him, without disturbing anybody, to steal quietly down stairs and to depart, unobserved, by way of the front door. He sturdily denied that the footprints on the gravel soil were his. He firmly declared his innocence, and that, while he felt that he could tell the name of the murderer, he did not wish to do so, for the reason that he had no proof to support his suspicion.

Tommy Taft died on the gallows. After the execution, people gathered to discuss the event. They began to think, too, as people sometimes will when they have condemned without thinking.

"That boy's pluckier than I'd a bin," murmured an old man, as he dragged his weather-beaten body slowly through the crowd. "He wasn't a guilty, Tommy Taft wasn't."

Nobody knew the speaker, and nobody cared for what he said.

Clio with her flickering light

And book of valued lore,

Comes down the ages dark and bright,

Our interest to implore.

She walks with glad, majestic mien,

Proud of her knowledge gained,

E'en while she mourns from having seen

Man's life so dulled and pained.

Her face with lines of care is wrought,

From searching mystery's cause,

And dealing with the hidden thought

Of nature's subtle laws.

Yet still she blushes with new life

In sight of actions fine,

And pales with anguish at the strife

Of evil's dread design.

She stops to sing her grandest lays

When, in creation's heat,

She sees evolved a higher phase

Of life's fruitions sweet.

'Twas thus in days of Genesis

When man came forth supreme;

'Twas thus in days of Nemesis

When Love did dare redeem.

And thus 'twill be in future days

When out from spirit-laws,

Shall be brought forth for lasting praise

The ever-great First cause.

Then gladly know this wondrous muse

Who walks the aisles of Time;

And dare not thoughtlessly refuse

Her book of lore sublime.

For in it is the precious force

Of spirit-life divine,

Which even through a winding course

Leads on to Wisdom's shrine.

The progenitor of the Phillips family in America was the Rev. George Phillips, son of Christopher Phillips of Rainham, St. Martin, Norfolk County, England, mediocris fortunæ. He entered Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, April, 20, 1610, then aged seventeen years, and received his bachelor's degree in 1613.

After his graduation he was settled in the ministry at Boxted, Essex County, England; but his strong attachment to the principles of the Nonconformists brought him into difficulties with some of his parishioners, and as the storm of persecution grew more dark and threatening, he resolved to cast his lot with the [250] Puritans, who were about to depart for the New World. On the 12th of April, 1630, he with his wife and two children embarked for America in the "Arbella," as fellow-passenger, with Gov. Winthrop, Sir Richard Saltonstall, and other assistants of the Massachusetts Company, and arrived at Salem on the 12th of June, where, shortly afterwards, his wife died and was buried by the side of Lady Arabella Johnson.

Mr. Phillips was admitted "freeman," May 18, 1631; this being the earliest date of any such admission. For fourteen years he was the pastor of the church at Watertown, a most godly man, and an influential member of the small council that regulated the affairs of the colony. His share in giving form and character to the institutions of New England is believed to have been a very large one. He died on the 1st of July, 1644, aged about fifty-one years.

The son of the foregoing, born in Boxted, England, in 1625, and graduated from Harvard College in 1650, became in 1651 the Rev. Samuel Phillips of Rowley, Mass. He continued as pastor over this parish for a period of forty-five years. He was highly esteemed for his piety and talents, which were of no common order; and he was eminently useful, both at home and abroad.

In September, 1687, an information was filed by one Philip Nelson against the Rev. Samuel Phillips, for calling Randolph "a wicked man;" and for this "crime" (redounding to his honor) he was committed to prison.

He was married in October, 1651, to Sarah Appleton, the daughter of Samuel and Mary (Everhard) Appleton of Ipswich. He died April 22, 1696, greatly beloved and lamented. His inventory amounted to nine hundred and eighty-nine pounds sterling. In November, 1839, a chaste and handsome marble monument was placed over the remains of Mr. Phillips and his wife, in the burial-ground at Rowley, by the Hon. Jonathan Phillips of Boston, their great-great-great-grandson.

He left two sons, the younger of whom, George (1664-1739, Harvard 1686), became an eminent clergyman, the Rev. George Phillips, first of Jamaica, L.I., and afterwards of Brookhaven. The elder son, Samuel, chose the occupation of a goldsmith, and settled in Salem. It is from this Samuel of Salem that the two Boston branches of the Phillips family have descended.

A younger son of Samuel, the Hon. John Phillips, was born June 22, 1701. He became a successful merchant of Boston, was a deacon of Brattle-street Church, a colonel of the Boston Regiment, a justice of the peace and of the quorum, and a representative of Boston for several years in the General Court. He married, in 1723, Mary Buttolph, a daughter of Nicholas Buttolph of Boston. She died in 1742; and he next married, Abigail Webb, a daughter of Rev. Mr. Webb of Fairfield, Conn. He died April 19, 1768, and was buried with military honors. According to the records, he was "a man much devoted to works of benevolence."