The Project Gutenberg eBook, Adventures in New Guinea, by James Chalmers This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Adventures in New Guinea Author: James Chalmers Release Date: February 6, 2006 [eBook #17694] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ADVENTURES IN NEW GUINEA***

Transcribed from the 1886 Religious Tract Society edition by David Price, email ccx074@coventry.ac.uk

THE R. T. S. LIBRARY—ILLUSTRATED

WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56, Paternoster Row; 65, St. Paul’s Churchyard;

and 164, Piccadilly

1886.

p. 4london:

printed by william clowes and sons, limited,

stamford street and charing cross.

Public attention has been repeatedly and prominently directed to New Guinea during the last few months. The name often appears in our newspapers and missionary reports, and bids fair to take a somewhat prominent place in our blue-books. Yet very few general readers possess accurate information about the island itself, about the work of English missionaries there, or about the part New Guinea seems destined to play in Australian politics. Hence a brief sketch indicating the present state of knowledge on these points will be a fitting introduction to the narratives of exploration, of adventure, and of Christian work contained in this volume.

New Guinea, if we may take Australia as a continent, is the largest island in the world, being, roughly speaking, about 1400 miles long, and 490 broad at its widest point. Its northernmost coast nearly touches the equator, and its southernmost stretches down to 11° south latitude. Little more than the fringe or coastline of the island has been at all carefully explored, but it is known to possess magnificent mountain ranges, vast stretches of beautiful scenery, much land that is fruitful, even under native cultivation, and mighty rivers that take their rise far inland. Its savage p. 8inhabitants have aroused powerfully the interest and sympathy alike of Christian Polynesians and English missionaries, who, taking their lives in their hands, have, in not a few instances, laid them down in the effort to win New Guinea for Christ.

At some remote period of the past, New Guinea, in all probability, formed a part of Australia. Torres Strait itself is only about sixty miles wide; the water is shallow; shoals and reefs abound, giving the sailor who threads the intricate and dangerous navigation the impression that he is sailing over what was once solid earth.

The first European sailor who sighted the island was D’Abreu, in 1511; the honour of being first to land belongs most probably to the Portuguese explorer, Don Jorge De Meneses, in 1526, on his way from Malacca to the Moluccas.

Into the somewhat intricate history of the connection of the Dutch with the north-west coast of New Guinea we cannot here enter. As suzerain nominally under the Sultan of Tidore, they claim possession of the western part of the island as far east as Lat. 141° 47' E. The trade they carry on is said to be worth about 20,000l. a year. Dutch missionaries have for many years been stationed around the coast of Geelvink Bay.

In 1770, Captain Cook visited the south-west coast, and in 1775, an English officer, Forrest by name, spent some months on the north-east coast in search of spices. In 1793, New Guinea was annexed by two of the East p. 9India Company’s commanders, and an island in Geelvink Bay, Manasvari by name, was for a time held by their troops.

Partial surveys of the south coast were made in 1845 by Captain Blackwood, who discovered the Fly River; by Lieutenant Yule, in 1846, who journeyed east as far as the island to which he has given his name; and in 1848 by Captain Owen Stanley, who made a fairly accurate survey of the south-east coast.

The most important survey work along the coast of New Guinea was done in 1873 by H.M. ship Basilisk, under the command of Captain Moresby. He discovered the now-famous harbour, Port Moresby; he laid down the true eastern coastline of the island, discovering the China Straits, and exploring the north-east coast as far west as Huon Gulf.

In many parts of the world Christian missionaries have been the first to get on friendly terms with the natives, and thus to pave the way for developing the resources of a savage country and leading its inhabitants in the paths of progress and civilization. Pre-eminently has this been the case in South-eastern New Guinea. White men had landed before them, it is true; but for the most part only to benefit themselves, and not unfrequently to murder the natives or to entrap them into slavery. Christianity has won great victories in Polynesia, but no part of the globe has witnessed fouler crimes or more atrocious wickedness on the part of white men towards savage races.

p. 10The history of the work done by members of the London Missionary Society is already a long one. As far back as 1871, the Revs. A. W. Murray and S. McFarlane sailed from Maré, one of the Loyalty Islands, with eight native teachers, inhabitants of that group, with whom to begin the campaign against sin, superstition, and savagery in New Guinea. The first station occupied was Darnley Island, and Mr. Murray gives an incident that well illustrates the spirit in which these men, themselves trophies of missionary success, entered upon their work. Speaking about another island, the natives, in the hope of intimidating the teachers, said, “There are alligators there, and snakes, and centipedes.” “Hold,” said the teacher, “are there men there?” “Oh yes,” was the reply, “there are men; but they are such dreadful savages that it is no use your thinking of living among them.” “That will do,” replied the teacher. “Wherever there are men, missionaries are bound to go.” Teachers were stationed at the islands of Tauan and Sabaii. Later on, Yule Island and Redscar Bay were visited, and the missionaries returned to Lifu.

In 1872, Mr. Murray returned in the John Williams with thirteen additional teachers, and for the next two years superintended the mission from Cape York. In 1874, he was joined by the Revs. S. McFarlane and W. G. Lawes—who have both ever since that time laboured hard and successfully on behalf of the natives—and the steamer Ellengowan was placed at the service p. 11of the mission by the liberality of the late Miss Baxter, of Dundee. The native teachers experienced many vicissitudes. Some died from inability to stand the climate, some were massacred by the men they were striving to bless; but the gaps were filled up as speedily as possible, and the map recently issued (Jan. 1885) by the Directors of the Society shows that on the south-eastern coast of New Guinea, from Motumotu to East Cape, no less than thirty-two native teachers, some of them New Guinea converts, are now toiling in the service of the Gospel.

In 1877, the Rev. James Chalmers joined the mission, and it is hardly too much to say that his arrival formed an epoch in its history. He is wonderfully equipped for the work to which he has, under God’s Providence, put his hand, and is the white man best known to all the natives along the south coast. From the first he has gone among them unarmed, and though not unfrequently in imminent peril, has been marvellously preserved. He has combined the qualities of missionary and explorer in a very high degree, and while beloved as “Tamate” (Teacher) by the natives, has added enormously to the stock of our geographical knowledge of New Guinea, and to our accurate acquaintance with the ways of thinking, the habits, superstitions, and mode of life of the various tribes of natives.

Notwithstanding various expensive expeditions for the exploration of New Guinea, he has travelled the farthest yet into the interior. He has been as far as p. 12Lat. S. 9° 2' and Long. E. 147° 42½'. The farthest point reached by Captain Armit was about Lat. S. 9° 35' and Long. E. 147° 38'. Mr. Morrison merely reached a point on the Goldie River, when he was attacked and wounded by the natives. This compelled the party to return to Port Moresby.

Mr. Chalmers is still actively engaged in his work on the great island, and he has placed many of his journals and papers at the disposal of the Religious Tract Society, in the hope that their publication may increase the general store of knowledge about New Guinea, and may also give true ideas about the natives, the kind of Christian work that is being done in their midst, and the progress in it that is being made.

The prominence which New Guinea has assumed in the public mind lately is due much more to political than to religious reasons. England is a Christian nation, and there are numbers who rejoice in New Guinea as a signal proof of the regenerating power of the Gospel of Christ. Yet, to the Christian man, it is somewhat humiliating to find how deeply the press of our country is stirred by the statement that Germany has annexed the north coast of New Guinea, while it has hardly been touched by the thrilling story of the introduction of Christianity all along the south coast. The public mind is much exercised in discussing whether Her Majesty’s Government should annex the whole rather than proclaim a protectorate over a part; it hardly cares to remember the names of those who p. 13have died in trying to make known to the fierce Papuans our common brotherhood in Christ Jesus. One can understand that this is natural; still it will be an augury of good for the future of the English people, when, without losing any of their legitimate interest in public affairs, they care more for the victories won by faith alone, over ignorance, vice, and barbarism, than for the victories won by the rifle and sword, however just the cause may be in which these weapons are used.

For years past the idea has been gaining force in the public mind, both in the colonies and at home, that ultimately England would annex New Guinea. To any careful student of our history for the last century, it may appear strange that we have not done so long before. Our practice in the past has been to annex first, and to find reasons for it afterwards. To others, the very fact that even now the extremest step is only to proclaim a protectorate over a part, may appear to indicate that we are not quite so sure as we have been that annexation is wholly a blessing either to us or to the land annexed.

As already noted, in 1873, Captain Moresby did good service by accurately laying down the coastline of Eastern New Guinea. In accomplishing this, he discovered that there were several beautiful islands that had hitherto been considered part of the mainland. It is best perhaps to give what followed in his own words:—

“The importance of our discoveries led me to p. 14consider their bearing on Imperial and Australian interests. There lay the vast island of New Guinea, dominating the shores of Northern Australia, separated at one point by only twenty miles of coral reef from British possessions, commanding the Torres Straits route, commanding the increasing pearl-shell fisheries, and also the bêche-de-mer fishery. It was also improved by the richness and beauty, and the number of their fine vegetable products—fine timber, the cocoanut, the sago palm, sugar-cane, maize, jute, and various vegetable fibres, fruits and rich grasses—and my conclusion, after weighing all the considerations involved, was, that it was my duty to take formal possession of our discoveries in the name of Her Majesty. Such a course secured a postponement of occupation by any Power till our Government could consider its own interests, and whilst the acquisition of these islands might commend itself, and my act result in annexation on the one hand, it might be negatived on the other with easy simplicity, by a neglect to confirm it.”

Accordingly, a cocoanut tree was transformed into a flagstaff, the British flag was run up, and duly saluted with cheers and volleys, and a picture of the proceeding adorns the captain’s book as frontispiece.

Ever since that time events have tended in the direction of bringing New Guinea into closer relations with England. On the one hand, there has been the conviction that if we do not annex it some other country will, and thus threaten Australia. Then many p. 15Australians have looked upon New Guinea as a possible paradise for colonists, and have been eager to establish themselves securely upon its soil. The attempts in this direction have produced little but disaster to all concerned.

On the other hand, missionaries feel that there is much to be said on the same side. Perhaps the opinion of no one man deserves more weight than that of Mr. Chalmers. We give his views, as he expressed them before the protectorate was proclaimed.

“This question of the annexation of New Guinea is still creating a good deal of interest, and although at present the Imperial Government, through Lord Derby, has given its decision against annexation, yet the whole matter must, I have no doubt, be reconsidered, and the island be eventually annexed. It is to be hoped the country is not to become part of the Australian colonies—a labour land, and a land where loose money in the hands of a few capitalists is to enter in and make enormous fortunes, sacrificing the natives and everything else. If the Imperial Government is afraid of the expense, I think that can easily be avoided. Annex New Guinea, and save it from another power, who might harass our Australian colonies; administer it for the natives, and the whole machinery of government can be maintained by New Guinea, and allow a large overplus. We have all the experience of the Dutch in Java; I say, accept and improve.

“It will be said that, as a nation, Britain has never p. 16tried to govern commercially, or has not yet made money out of her governing; and why should she now? She does not want New Guinea. Why should she go to the expense of governing? Her colonies may be unsafe with a country of splendid harbours so near in the hands of a foreign power, and the people of that country need a strong, friendly, and just power over them, to save them from themselves and from the white man—whose gods are gold and land, and to whom the black man is a nuisance to be got rid of as soon as possible. Let Britain for these reasons annex, and from the day of annexation New Guinea will pay all her own expenses; the expenses of the first three years to be paid with compound interest at the end of that period.

“Let us begin by recognizing all native rights, and letting it be distinctly understood that we govern for the native races, not the white men, that we are determined to civilize and raise to a higher level of humanity those whom we govern, that our aim will be to do all to defend them and save them from extermination by just humanitarian laws—not the laws of the British nation—but the laws suited for them. It will not take long for the natives to learn that not only are we great and powerful, but we are just and merciful, and we seek their good.

“That established, I would suggest appointing officers in every district, whose duty it would be to govern through the native chief, and see that every p. 17native attended to plantations. A native planting tea, sugar, coffee, maize, cinchona, etc., to be allowed a bounty, and when returns arrived to be allowed so much per pound sterling. All these things to be superintended by the said officer.

“Traders would soon swarm, but no one should be allowed to trade with natives directly, but only through the Government.

“All unoccupied land to belong to the Government, and to be leased to those wishing land. No native should be allowed to part with land, and if desirous to sell, then only to the Government, who would allow him a reasonable price. Every land transaction to be made through Government; no land to be sold, only leased.

“The land revenue will be immense, and after paying all expenses, will leave much for improvements and the education of the people. Stringent laws passed directly annexation takes place to prevent importation of arms and spirits will be a true safeguard for the natives.

“As a nation, let Britain, in the zenith of her power and greatness, think kindly of the native races, and now for once in her history rule this great island for right and righteousness, in justice and mercy, and not for self and pelf in unrighteousness, blood, and falsehood. It is to be hoped that future generations of New Guinea natives will not rise up to condemn her, as the New Zealanders have done, and to claim p. 18their ancient rights with tears now unheeded. I can see along the vista of the future, truth and righteousness in Britain’s hands, and the inhabitants of New Guinea yet unborn blessing her for her rule; if otherwise, God help the British meanness, for they will rise to pronounce a curse on her for ever!”

In 1883, the Queensland Government did formally annex their huge neighbour; but this act was subsequently repudiated by the Home Government. Towards the end of 1884, it was decided to announce a formal protectorate over a large portion of the southern shores of New Guinea.

The official ceremony took place on Nov. 6th, 1884, at Port Moresby. Five ships of war at once gave dignity to the proceeding by their presence, and astonished the natives by their salutes. About fifty chiefs were brought on board the Commodore’s ship, the Nelson, by the Rev. W. G. Lawes. To Boevagi, the chief of the Port Moresby tribe, was entrusted the responsibility of upholding the authority and dignity of England in the island. He was presented with an ebony stick, into the top of which had been let a florin, with the Queen’s head uppermost. Mr. Lawes conveyed to Boevagi the meaning of the Commodore’s words when he gave the stick. “I present you with this stick, which is to be an emblem of your authority; and all the tribes who are represented by the chiefs here are to look to the holder of this stick. Boevagi, this stick represents the Queen of England, p. 21and if at any time any of the people of these tribes have any grievance or anything to say, they are, through the holder of this stick, to make it known to the Queen’s officers, in order that it may be inquired into.”

The formal protectorate was announced in the following terms:—

“To all to whom these presents shall come, greeting:—Whereas it has become essential for the lives and properties of the native inhabitants of New Guinea, and for the purpose of preventing the occupation of portions of that country by persons whose proceedings, unsanctioned by any lawful authority, might tend to injustice, strife, and bloodshed, and who, under the pretence of legitimate trade and intercourse, might endanger the liberties and possess themselves of the lands of such native inhabitants, that a British protectorate should be established over a certain portion of such country and the islands adjacent thereto; and whereas Her Majesty, having taken into her gracious consideration the urgent necessity of her protection to such inhabitants, has directed me to proclaim such protection in a formal manner at this place,—now I, James Elphinstone Erskine, Captain in the Royal Navy and Commodore of the Australian Station, one of Her Majesty’s naval aides-de-camp, do hereby, in the name of Her Most Gracious Majesty, declare and proclaim the establishment of such protectorate over such portions of the coast and the adjacent islands as is more particularly p. 22described in the schedule hereunto annexed; and I hereby proclaim and declare that no acquisition of land, whensoever or howsoever acquired, within the limits of the protectorate hereby established will be recognized by Her Majesty; and I do hereby, on behalf of Her Majesty, command and enjoin all persons whom it may concern to take notice of this proclamation.

“Schedule.

“All that portion of the southern shores of New Guinea commencing from the boundary of that portion of the country claimed by the Government of the Netherlands on the 141st meridian of east longitude to East Cape, with all the islands adjacent thereto south of East Cape to Kosmann Island inclusive, together with the islands in the Goschen Straits.

“Given on board Her Majesty’s ship Nelson, at the harbour of Port Moresby, on the 6th day of November, 1884.”

The die has thus been cast. Already rumours that seem to have some foundation are in the air that the protectorate is soon to become annexation. It should be the aim of all to see that, by the force of public opinion, the last portion of the heathen world that has come under English protection shall have, as the years pass, many and solid reasons for thanking God that He has so guided its destinies as to unite them to our great Empire.

Somerset—Murray Island—Darnley Island—Boera—Moresby—Trip inland—Sunday at Port Moresby—Native funeral ceremonies—Tupuselei—Round Head—Native salutations—Kerepunu—Teste Island—Hoop-iron as an article of commerce—Two teachers landed—A tabooed place—Moresby and Basilisk Islands—South Cape—House building—Difficulties with the natives—An anxious moment—Thefts—Dancing and cooking—Visit to a native village—Native shot on the Mayri—Mr. and Mrs. Chalmers in danger—Arrival of the Ellengowan.

Towards the close of 1877, Mr. Chalmers and Mr. McFarlane visited New Guinea for the purpose of exploring the coast, landing native teachers at suitable spots, and thus opening the way for future missionary effort. What follows is given in Mr. Chalmers’s words:—

We left Sydney by the Dutch steamer William M’Kinnon, on September 20th, 1877, for Somerset. The sail inside the Barrier Reef is most enjoyable. The numerous islands passed, and the varied coast scenery make the voyage a very pleasant one—especially p. 24with such men as our captain and mates. On Sunday, the 30th, we reached Somerset, where we were met by the Bertha, with Mr. McFarlane on board of her. Mr. McFarlane was soon on board of the steamer to welcome us, and remained with us till the evening. There was very little of the Sabbath observed that day—all was bustle and confusion. Quite a number of the pearl-shelling boats were at Somerset awaiting the arrival of the steamer, and the masters of these boats were soon on and around the steamer receiving their goods.

On Tuesday, October 2nd, we left Somerset in the Bertha, for Murray Island, anchoring that night off Albany. On Wednesday night, we anchored off a sandbank, and on Thursday, off a miserable-looking island, called Village Island. On Friday, we came to York Island, where we went ashore and saw only four natives—one man and three boys. At eleven p.m. on Saturday, we anchored at Darnley Island. This is a fine island, and more suitable for vessels and landing goods than Murray, but supposed to be not so healthy. The island is about five hundred feet in height, in some parts thickly wooded, in others bare. It was here the natives cut off a boat’s crew about thirty years ago, for which they suffered—the captain landing with part of his crew, well-armed, killing many and chasing them right round the island. They never again attempted anything of the kind. As a native of the island expressed himself on the subject:—p. 25“White fellow, he too much make fright, man he all run away, no want see white fellow gun no more.” In 1871, the first teachers were landed here.

The Sunday morning was fine, and we resolved to spend a quiet forenoon on shore. We landed after breakfast, and walked through what must be in wet weather a deep swamp, to the mission house on the hill. Gucheng, the Loyalty islander, who is teacher here, looks a good determined fellow. The people seem to live not far from the mission house, so did not take long to assemble. There were about eighty at the service, including a few Australians employed by one of the white men on the island to fish for trepang. The Darnley islanders appear a much more interesting people than the Australians. Many of those present at the service were clothed. They sang very well indeed such hymns as “Come to Jesus,” “Canaan, bright Canaan,” which, with some others, have been translated into their language. Mr. McFarlane addressed them, through the teacher, and the people seemed to attend to what was said.

Because of a strong head wind, we could not leave the next day, so Mr. McFarlane and I returned to the shore. We found the children collected in Gucheng’s house, learning to write the letters on slates. There were very few girls present—indeed, there are not many girls on the island, so many have been destroyed by their fathers at birth. We strolled about and visited the large cocoanut plantation belonging p. 26to the society. On our return we found the teacher and a number of natives collected near the beach. They had just buried a man who had died the night before—so Christian burial has begun. Formerly, the body would have been hung up and tapped, to allow the juices to run out, which would have been drunk by the friends. We returned to the mission house for dinner. I was glad to find so many boys living with Gucheng. They were bright, happy little fellows, romping about, enjoying themselves.

We did not get away from Darnley Island till the morning of Wednesday, the 10th. The navigation between Darnley and Murray Islands is difficult, arising from various reefs and currents. Although only twenty-seven miles separate the two, it was Friday night before we anchored at Murray Island. We went ashore the same night.

On Saturday, we climbed to the highest point of the island, seven hundred feet high. There seems to be no lack of food, chiefly grown inland. From the long drought, the island presented in many places a parched look, and lacked that luxuriance of vegetation to which we had been so long accustomed on Rarotonga.

At the forenoon meeting on Sunday there were nearly two hundred present. Mr. McFarlane preached. A few had a little clothing on them; some seemed attentive, but the most seemed to consider the occasion a fit time for relating the week’s news, or of p. 27commenting on the strangers present. The Sabbath is observed by church attendance and a cessation from work. There is not much thieving on the island; they are an indolent people. The school is well attended by old and young, and Josiah, the teacher, has quite a number of children living with him. They sing very well.

Several of the old men here wear wigs. It seems when grey hairs appear they are carefully pulled out; as time moves on they increase so fast that they would require to shave the head often, so, to cover their shame, they take to wigs, which represent them as having long, flowing, curly hair, as in youth. Wigs would not astonish the Murray islanders, as Mr. Nott’s did the Tahitians after his return from England. They soon spread the news round the island that their missionary had had his head newly thatched, and looked a young man again.

On Monday, the teachers’ goods and mission supplies were put on board the Bertha. On Tuesday afternoon, after everything was on board, a farewell service was held with the teachers, and early on Wednesday morning we left Murray Island for New Guinea. On Friday, we made New Guinea, off Yule Island, and about sunset on October 21st we anchored about five miles off Boera. Near to the place where we anchored was a low swampy ground covered with mangrove. We could see Lealea, where there has been so much sickness. It presented the same low, p. 28swampy, unhealthy appearance. Soon after we anchored a canoe came alongside with Mr. Lawes and Piri on board. Mr. Lawes did not seem so strong as I remembered him eleven years ago, yet he looked better than I had expected to see him. He has suffered greatly from the climate. Piri is a strong, hearty fellow; the climate seems to have had little effect on him. They remained some time on board, when they went ashore in the vessel’s boat—Piri taking the teachers and their wives ashore with him. The wind was ahead, and too strong for the canoe, so the men who came off in her with Mr. Lawes and Piri remained on board the Bertha till midnight, when the wind abated. When the boat was leaving, they shouted to Mr. Lawes to tell us not to be afraid, as they would not steal anything. They remained quietly on board till two a.m.

Mr. McFarlane and I went ashore in the morning. The country looked bare and not at all inviting. This is now the most western mission station on New Guinea proper. Piri has a very comfortable house, with a plantation near to it. The chapel, built principally by himself and wife, is small, but comfortable, and well suited for the climate. The children meet in it for school. The village has a very dirty, tumbledown appearance.

The widows of two teachers who died last year shortly after their arrival in the mission were living with Piri. We took them on board, with their things, p. 29to accompany us to the new mission. I returned ashore with the boat to fetch away the remainder of the things and teachers who were ashore, and when ready to return found the vessel too far off to fetch her, so, after pulling for some time, we up sail and away for Port Moresby. Piri and his wife came with us in their large canoe. We saw several dugongs on the way, which some esteem extra good food. Tom, one of the Loyalty Island teachers, who was in the boat with us, expressed their edible qualities thus: “You know, sir, pig, he good.” “Yes, Tom, it is very good.” “Ah, he no good; dugong, he much good.” It must be good when a native pronounces it to be better than pork.

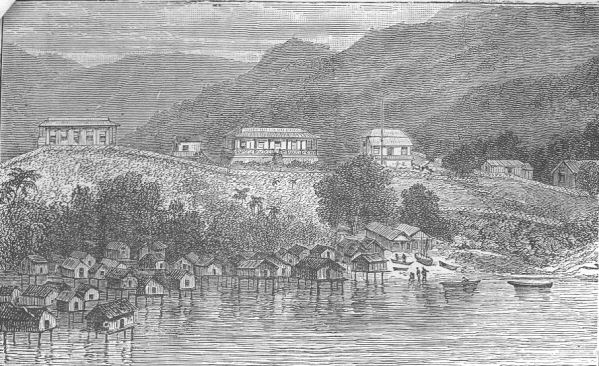

We arrived at Port Moresby about six o’clock. I cannot say I was much charmed with the place, it had such a burnt-up, barren appearance. Close to the village is a mangrove swamp, and the whole bay is enclosed with high hills. At the back of the mission premises, and close to them, is a large swampy place, which in wet weather is full of water. There can be no doubt about Port Moresby being a very unhealthy place. We went ashore for breakfast next day, and in the afternoon visited the school; about forty children were present—an unusually large number. Many of the children know the alphabet, and a few can spell words of two or three letters. In walking through the village in the afternoon we saw the women making their crockery pots, preparing for the men’s return p. 30from the Gulf, the next north-west season, with large quantities of sago. We visited the graves of the teachers, which are kept in good order. They are all enclosed by a good fence. Within the same enclosure is one little grave that will bind New Guinea close to the hearts of Mr. and Mrs. Lawes. Over them all may be written—“For Christ’s sake.”

In returning from the graves, we met a man in mourning, whose wife had been killed in a canoe by natives about Round Head. He and his friends had resolved to retaliate, but through the influence of the teachers they did not do so. The teachers from the villages to the east of Port Moresby came in this afternoon, looking well and hearty. Some of them have suffered a good deal from fever and ague, but are now becoming acclimatized. The natives of the various villages are not now afraid of one another, but accompany their teachers from place to place. Men, women, and children smoke, and will do anything for tobacco. The best present you can give them is tobacco; it is the one thing for which they beg.

As it was decided that the vessel should not leave before Tuesday of the next week, Mr. McFarlane and I took a trip inland. I was anxious to see for myself if anything could be done for the natives living in the mountains. Mr. Goldie, a naturalist, with his party, was about ten miles inland. He himself had been at Port Moresby for some days, and, on hearing of our plans, he joined us, and we proceeded first to his camp. p. 31We left Port Moresby about half-past five on Thursday morning, and crossed the low ground at the back of the mission house. We ascended the hill which runs all along the coast in this district at a part about three hundred feet high, and then descended into a great plain. At present the plain is dry and hard, from the long drought, and very little of anything green is to be seen. There are a few small gum-trees, and great herds of wallabies were jumping about. The greater part of this plain is under water in the wet seasons. We walked about ten miles in an east-north-east direction, keeping the Astrolabe Range to our right, when we came to the camp, close by a large river—the Laroki. Being afraid of alligators, we preferred having water poured over us to bathing in the river.

Our party was a tolerably large one—Ruatoka (the Port Moresby teacher), some Port Moresby natives, and four Loyalty Island teachers, on their way to East Cape. We did not see a strange native all the way. We had our hammocks made fast in the bush by the river side, and rested until three p.m., when we started for another part of the river about seven miles off, in a south-east direction. Mr. Goldie also shifted his camp. After sunset we reached the point where the river was to be crossed, and there we meant to remain for the night.

We had a bath, then supper, and evening prayers; after which we slung our hammocks to the trees, in which we rested well. It was a strangely weird-looking p. 32sight, and the noises were of a strange kind—wallabies leaping past, and strange birds overhead. Mr. Goldie’s Maré men joined with their countrymen, the teachers, in singing some of Sankey’s hymns in English. Soon sleep came, and all seemed quiet.

At three a.m. of the 26th we struck camp, and after morning prayers we began to cross the river, which was not over four feet in the deepest part. It was here Mr. Lawes crossed when he first visited the inland tribes; so now, led by Ruatoka, we were on his track. The moon was often hidden by dark clouds, so we had some difficulty in keeping to the path. We pressed on, as we were anxious to get to a deserted village which Mr. Goldie knew to breakfast. We reached the village about six, and after we had partaken of breakfast we set off for the mountains. When we had gone about four miles the road became more uneven. Wallabies were not to be seen, and soon we were in a valley close by the river, which we followed for a long way, and then began to ascend. We climbed it under a burning sun, Ruatoka calling out, Tepiake, tepiake, tepiake (Friends, friends, friends). Armed natives soon appeared on the ridge, shouting, Misi Lao, Misi Lao. Ruatoka called back, Misi Lao (Mr. Lawes), and all was right—spears were put away and they came to meet us, escorting us to a sort of reception-room, where we all squatted, glad to get in the shade from the sun. We were now about 1100 feet above the sea level. p. 33We were surprised to see their houses built on the highest tree-tops they could find on the top of the ridge. One of the teachers remarked, “Queer fellows these; not only do they live on the mountain tops, but they must select the highest trees they can find for their houses.” We were very soon friends; they seemed at ease, some smoking tobacco, others chewing betel-nuts. I changed my shirt, and when those near me saw my white skin they raised a shout that soon brought the others round. Bartering soon began—taro, sugar-cane, sweet yams, and water were got in exchange for tobacco, beads, and cloth.

After resting about two hours, we proceeded to the next village, five miles further along the ridge. Some of our party were too tired to accompany us; they remained where we expected to camp for the night. After walking some miles, we came unexpectedly on some natives. As soon as they saw us they rushed for their spears, and seemed determined to dispute our way. By a number of signs—touching our chins with our right hands, etc.—they understood we were not foes, so they soon became friendly. They had their faces blackened with soot, plumbago, and gum, and then sprinkled over with white; their mouths and teeth were in a terrible mess from chewing the betel-nut. On our leaving them, they shouted on to the next village. An old man lay outside on the platform of the next house we came to; he looked terribly frightened as we approached him, but as, instead of p. 34injuring him, we gave him a present, he soon rallied, and got us water to drink. By-and-by a few gathered round. We understood them to say the most of the people were away on the plains hunting for wallabies. One young woman had a net over her shoulders and covering her breasts, as a token of mourning—an improvement on their ordinary attire, which is simply a short grass petticoat—the men nil.

After a short stay, we returned to where we thought of camping for the night, but for want of water we went on to the village we had visited in the forenoon. We slung our hammocks in the reception room, had supper, and turned in for the night. It felt bleak and cold, and the narrowness of the ridge made us careful, even in our sleep, lest we should fall out and over. On coming across the highest peak in the afternoon, we had a magnificent view of Mount Owen Stanley, with his two peaks rising far away above the other mountains by which he is surrounded. It must have been about thirty miles off, and, I should think, impossible to reach from where we were. We were entirely surrounded by mountains: mountains north, east, south, and west—above us and below us. I question if it will ever be a country worth settling in.

We were anxious to spend the Sabbath at Port Moresby, so, leaving the most of our party, who were too tired to come with us, to rest till Monday, Mr. McFarlane, Ruatoka, and I set off on our return very p. 35early on Saturday morning, and had strangely difficult work in getting down the mountain side and along the river. Fireflies danced all round in hundreds, and we awakened many strange birds before their time, which gave forth a note or two, only to sleep again. Before daylight, we were at Mr. Goldie’s camp, where we had breakfast, and hurried on for the river. We rested a short time there, and then away over plains to Port Moresby, which we reached about midday, tired indeed and very footsore. Oh, that shoemakers had only to wear the boots they send to missionaries!

Early on Sunday morning, a great many natives went out with their spears, nets, and dogs, to hunt wallabies. A goodly number attended the forenoon service, when Mr. Lawes preached. A good many strangers were present from an inland village on the Astrolabe side. There is not yet much observance of the Sabbath. Poi, one of the chief men of the place, is very friendly: he kept quite a party of his inland friends from hunting, and brought them to the services. Mr. Lawes preached again in the afternoon. As we went to church in the afternoon the hunters were returning: they had evidently had a successful day’s hunting. During the day a canoe came in from Hula, laden with old cocoanuts, which were traded for pottery.

In the evening, an old sorceress died, and great was the wailing over her body. She was buried on the p. 36Monday morning, just opposite the house in which she had lived. A grave was dug two feet deep, and spread over with mats, on which the corpse was laid. Her husband lay on the body, in the grave, for some time, and, after some talking to the departed spirit, got up, and lay down by the side of the grave, covered with a mat. About midday, the grave was covered over with the earth, and friends sat on it weeping. The relatives of the dead put on mourning by blackening their bodies all over, and besmearing them with ashes.

On the 31st, the Bertha left for Kerepunu. As I was anxious to see all the mission stations along the coast between Port Moresby and Kerepunu, I remained, to accompany Mr. Lawes in the small schooner Mayri. We left on the following day, and sailed down the coast inside the reef. We arrived at Tupuselei about midday. There were two teachers here, and Mr. Lawes having decided to remove one, we got him on board, and sailed for Kaili. The villages of Tupuselei and Kaili are quite in the sea. I fear they are very unhealthy—mangroves and low swampy ground abound. The Astrolabe Range is not far from the shore we were sailing along all day. There is a fine bold coast line, with many bays.

In the early morning, our small vessel of only seven tons was crowded with natives. We left the vessel about nine a.m. for a walk inland, accompanied by a number of natives, who all went to their houses for p. 37their arms before they would leave their village. They have no faith whatever in one another. We passed through a large swamp covered with mangroves—then into a dense tropical bush, passing through an extensive grove of sago palms and good-sized mango trees. The mangoes were small—about the size of a plum—and very sweet. At some distance inland I took up a peculiar-looking seed; one of the natives, thinking I was going to eat it, very earnestly urged me to throw it away, and with signs gave me to understand that if I ate it I should swell out to an enormous size, and die.

We walked about seven miles through bush, and then began the ascent of one of the spurs of the Astrolabe. On nearing the inland village for which we were bound, the natives became somewhat afraid, and the leader stopped, and, turning to Mr. Lawes, asked him if he would indeed not kill any of the people. He was assured all was right, and then he moved on a few paces, to stop again, and re-inquire if all was right. When reassured, we all went on, not a word spoken by any one, and so in silence we entered the village. When we were observed, spears began rattling in the houses; but our party shouted, Maino, maino (Peace, peace), Misi Lao, Misi Lao. The women escaped through the trap-doors in the floors of their houses, and away down the side of the hill into the bush. We reached the chief’s house, and there remained.

p. 38The people soon regained confidence, and came round us, wondering greatly at the first white men they had ever seen in their village. The women returned from their flight, and began to cook food, which, when ready, they brought to us, and of which we all heartily partook. We gave them presents, and they would not suffer us to depart till they had brought us a return present of uncooked food. They are a fine, healthy-looking people, lighter than those on the coast. Many were in deep mourning, and frightfully besmeared. There are a number of villages close by, on the various ridges. We returned by a different way, following the bed of what must be in the rainy season a large river. The banks were in many places from eight to nine feet high.

On the following morning, November 3rd, we weighed anchor and set sail, passing Kapakapa, a double village in the sea. The houses are large and well built. There are numerous villages on the hills at the back of it, and not too far away to be visited. We anchored off Round Head, which does not, as represented on the charts, rise boldly from the sea. There is a plain between two and three miles broad between the sea and the hill called Round Head. There are many villages on the hills along this part of the coast. We anchored close to the shore. A number of natives were on the beach, but could not be induced to visit us on board. We went ashore to them after dinner. They knew Mr. Lawes by name p. 39only, and became more easy when he assured them that he was really and truly Misi Lao. They professed friendship by calling out, Maino, maino, catching hold of their noses, and pointing to their stomachs. After a little time, two ventured to accompany Mr. Lawes on board, and received presents. I remained ashore astonishing others by striking matches, and showing off my arms and chest. The women were so frightened that they all kept at a respectful distance. These are the natives from an inland village that killed a Port Moresby native about the beginning of the year. When those who accompanied Mr. Lawes on board the Mayri returned to the shore, they were instantly surrounded by their friends, who seized the presents and made off. They had received fish, biscuit, and taro. The taro and fish were smelt all over, and carefully examined before eaten. The biscuit was wrapped up again in the paper.

On Sunday, the 4th, we were beating down through innumerable reefs, and at eight p.m. we anchored about three miles from Hula. The following morning we went up to the village, the Mayri anchoring close by the houses. The country about here looks fine and green, a very striking contrast to that around Port Moresby. The further east we get from Port Moresby, the finer the country looks. The people are also superior—finer-made men and women, and really pretty boys and girls—more, altogether, like our eastern South Sea Islanders. The married women p. 40spoil their looks by keeping their heads shaved. They seem fond of their children: men and women nurse them. They were busy preparing their large canoes to visit Port Moresby, on the return of the Port Moresby canoes from the west with sago.

About three in the afternoon, an old woman made her appearance at the door of the mission house, bawling out, “Well, what liars these Hula people are; some of them were inland this morning, and the chief asked them if Misi Lao had come, and they said no.” The chief, who saw the vessel from the hill top where his village is, thought it strange the vessel should be there without Misi Lao, so sent this woman to learn the truth. She received a present for herself and the chief, and went away quite happy.

Next morning, November 6th, we left Hula with a fair wind, and were anchored close to Kerepunu by nine o’clock. The Bertha was anchored fully two miles off. Kerepunu is a magnificent place, and its people are very fine-looking. It is one large town of seven districts, with fine houses, all arranged in streets, crotons and other plants growing about, and cockatoos perching in front of nearly every house. One part of the population plant, another fish, and the planters buy the fish with their produce. Men, women, and children are all workers; they go to their plantations in the morning and return to their homes in the evening, only sick ones remaining at home; thus accounting for the number of scrofulous people we saw going p. 41about when we first landed. They have a rule, to which they strictly adhere all the year round, of working for two days and resting the third.

The Bertha arrived here on Friday evening. Mrs. Chalmers was at the forenoon service on the Sunday, and found there a large congregation. The service was held on the platform of one of the largest houses. Anedered preached, a number sitting on the platform, others in the house, others on the ground all round, and many at the doors of their own houses, where they could hear all that was said.

Mr. Lawes decided to remain at Kerepunu to revise for the press a small book Anedered has been preparing, and to follow us to Teste Island in the Ellengowan. We left Kerepunu on the morning of November 8th, the Mayri leaving at the same time, to sail down inside the surf. We went right out to sea, so as to beat down, had fine weather, and were off Teste Island by the 16th. After dinner we took the boat, and with the captain went in on the east side of the island through the reef, to sound and find anchorage.

When we reached the lagoon, a catamaran with three natives on it came off to us. We asked for Koitan, the chief, which at once gave them confidence in us, so that they came alongside, one getting into the boat. He expressed his friendship to us in the usual way, viz. by touching his nose and stomach, and, being very much excited, seized hold of Mr. p. 42McFarlane and rubbed noses with him, doing the same to me. He received a present of a piece of hoop-iron and some red braid, which greatly pleased him. We found the water was deep enough over the reef for the vessel, and good anchorage inside. We went on to the village, to see about the supply of water.

The people were very friendly, and crowded round us. We were led up to a platform in front of one of their large houses, and there seated and regaled with cocoanuts. The natives here are much darker than are those at Kerepunu; most of them suffer from a very offensive-looking skin disease, which causes the skin to peel off in scales. In their conversation with one another I recognized several Polynesian words. The water is obtained by digging in the sand, and is very brackish.

We came to anchor next morning, and soon were surrounded with canoes, and our deck swarmed with natives trading their curios, yams, cocoanuts, and fish for beads and hoop-iron. Many were swearing friendship, and exchanging names with us, in hopes of getting hoop-iron. There is as great a demand for hoop-iron here as for tobacco at Port Moresby. They told us they disliked fighting, but delighted in the dance, betel-nut, and sleep. The majority have jet black teeth, which they consider very beautiful, and all have their noses and ears pierced, with various sorts of nose and ear rings, chiefly made from shell, p. 43inserted. A crown piece could easily be put through the lobe of their ears.

We went ashore in the afternoon. There are three villages, all close to one another. Their houses are built on poles, and are shaped like a canoe turned bottom upwards, others like one in the water. They ornament their houses on the outside with cocoanuts and shells. The nabobs of the place had skulls on the posts of their houses, which they said belonged to the enemies they had killed and eaten. One skull was very much fractured; they told us it was done with a stone axe, and showed us how they used these weapons.

We tried to explain to them that no one was to come to the vessel the next day, as it was a sacred day. In the early morning, some canoes came off to trade, but we sent them ashore; a few more followed about breakfast-time, which were also sent ashore. In the afternoon, our old friend of the preceding day came off, with his wife and two sons. He called out that he did not wish to come on board, but that he had brought some cooked food. We accepted his present, and he remained with his family in his canoe alongside the vessel for some time, and then went quietly ashore. We had three services on board, one in the forenoon in Lifuan, in the afternoon in Rarotongan, and in the evening in English.

As Teste Island is about twenty miles from the mainland, with a dead beat to it, I decided to seek p. 44for a position more accessible to New Guinea, and as I had not a teacher to spare for this little island, Mr. McFarlane decided to leave two of the Loyalty Island teachers here. It is fertile, and appears healthy, is two and a half miles long, and half a mile broad. A ridge of hills runs right through its centre from east-north-east to west-south-west. The natives have some fine plantations on the north side, and on the south and east sides they have yam plantations to the very tops of the hills. There are plantations and fruit-trees all round the island.

On Monday, I accompanied Mr. McFarlane when he went ashore to make arrangements to land his teachers and secure a house for them. The people seemed pleased that some of our party would remain with them. Mr. McFarlane at once chose a house on a point of land a good way from our landing-place, and at the end of the most distant village. The owner was willing to give up the house until the teachers could build one for themselves, so it was at once taken and paid for. We came along to our old friend’s place near the landing, when we were told that the house taken was a very bad one. In the first place, the position was unhealthy; in the second, that was the point where their enemies from Basilaki (Moresby Island) always landed when they came to fight, and the people could not protect the teachers if so far off when their foes came. All agreed in this, and a fine new house which had never been occupied p. 45was offered and taken, the same price being paid for it as for the other one. This house is close to the landing-place, and in the midst of the people. The owner of the first house offered to return the things, but we thought it would not be ruinous to let him keep them, their English value being about ten shillings.

We passed a tabooed place, or rather would have done so had we not been forced to take a circuitous path to the bush. None of the natives spoke as we passed the place, nor till we were clear of it; they made signs also to us to be silent. A woman had died there lately, and the friends were still mourning. There had been no dancing in the settlement since the death, nor would there be any for some days to come.

I think women are more respected here than they are in some other heathen lands. They seem to keep fast hold of their own possessions. A man stole an ornament belonging to his wife, and sold it for hoop-iron on board the Bertha. When he went ashore he was met on the beach by his spouse, who had in the meantime missed her trinket; she assailed him with tongue, stick, and stone, and demanded the hoop-iron.

The teachers were landed in the afternoon, and were well received. The natives all promised to care for them, and treat them kindly. There are about two hundred and fifty natives on the island. No Ellengowan appearing, we determined to leave this on p. 46Wednesday, the 21st, and to proceed to Moresby Island. Next morning we left, but, owing to light winds, we did not anchor in Hoop-Iron Bay, off Moresby Island, till the morning of the 22nd. The anchorage here is in an open roadstead. It is a very fine island—the vegetation from the water’s edge right up to the mountain tops. Plantations are to be seen all round. The people live in small detached companies, and are not so pleasant and friendly-looking a people as are the Teste islanders. This is the great Basilaki, and the natives are apparently the deadly foes of all the islanders round. Before we anchored, we were surrounded by catamarans (three small logs lashed together) and canoes—spears in them all.

Mr. McFarlane decided, as soon as we came to the island, that he would not land his teachers here; and I did not consider it a suitable place as a head station for New Guinea. We left Moresby Island at six a.m. on the 23rd inst., and beat through Fortescue Straits, between Moresby and Basilisk Islands. The scenery was grand—everything looked so fresh and green, very different from the deathlike appearance of Port Moresby and vicinity. The four teachers were close behind us, in their large whale-boat, with part of their things. On getting out of the Straits, we saw East Cape; but, as there was no anchorage there, we made for Killerton Island, about ten miles from the Cape. The wind being very light, it was eight p.m. before we anchored: the boat got up an hour after p. 47us. There was apparently great excitement ashore; lights were moving about in all directions, but none came to us. In the morning, a catamaran with two boys ventured alongside of us; they got a present, and went away shouting. Soon we were surrounded with catamarans and canoes, with three or four natives in each. They had no spears with them, nor did they kill a dog on our quarter-deck, as they did on that of the Basilisk. They appeared quite friendly, and free from shyness. They brought their curios to barter for beads, red cloth, and the much-valued hoop-iron. The whole country looked productive and beautiful. After breakfast, we went ashore, and were led through swampy ground to see the water. On our return to the shore, we went in search of a position for the mission settlement, but could not get one far enough away from the swamp, so we took the boat and sailed a mile or two nearer the Cape, where we found an excellent position near a river. Mr. McFarlane obtained a fine new house for the teachers, in which they are to remain till they get a house built. We took all the teachers’ goods ashore, which the natives helped to carry to the house. One man, who considered himself well dressed, kept near us all day. He had a pair of trousers, minus a leg: he fastened the body of the trousers round his head, and let the leg fall gracefully down his back.

On the following morning, two large canoes—twenty p. 48paddles in each—came in from somewhere about Milne Bay. They remained for some time near the shore, getting all the news they could about us from the shore-folk; then the leader amongst them stood up and caught his nose, and pointed to his stomach—we doing the same. The large canoes went ashore, and the chief came off to us in a small one. We gave him a present, which greatly pleased him. After breakfast, we went ashore to hold a service with the teachers. We met under a large tree, near their house. About six hundred natives were about us, and all round outside of the crowd were men armed with spears and clubs. Mr. McFarlane preached. When the first hymn was being sung, a number of women and children got up and ran into the bush. The service was short; at its close we sat down and sang hymns, which seemed to amuse them greatly. The painted and armed men were not at all pleasant-looking fellows.

At two in the morning (Monday), we weighed anchor and returned to Moresby Island. The wind was very light, and we had to anchor at the entrance to Fortescue Straits. Next morning, we sailed through the Straits, and, on coming out on the opposite side, we were glad to see the Bertha beating about there. By noon we were on board the Bertha, and off for South Cape, the Mayri going to Teste Island with a letter, telling the captain of the Ellengowan to follow us, and also to see if the teachers were all right.

p. 49By evening we were well up to South Cape. The captain did not care to get too near that night, and stood away till morning. About ten next morning I accompanied the captain in the boat, to sound and look for anchorage, which we found in twenty-two fathoms, near South-West Point. By half-past fire that evening we anchored. The excitement ashore was great, and before the anchor was really down we were surrounded by canoes. As a people, they are small and puny, and much darker than the Eastern Polynesians. They were greatly excited over Pi’s baby, a fine plump little fellow, seven months old, who, beside them, seemed a white child. Indeed, all they saw greatly astonished them. Canoes came off to us very early in the morning. About half-past seven, when we were ready to go ashore, there arose great consternation amongst the natives. Three large war canoes, with conch-shells blowing, appeared off the mainland and paddled across the Mayri Straits. Soon a large war canoe appeared near the vessel. A great many small canoes from various parts of the mainland were ordered off by those on whose side we were anchored. They had to leave. On their departure a great shout was raised by the victorious party, and in a short time all returned quietly to their bartering. It seemed that the Stacy Islanders wished to keep all the bartering to themselves. They did not wish the rest to obtain hoop-iron or any other foreign wealth. They are at feud with one p. 50party on the mainland, and I suppose in their late contests have been victorious, for they told us with great exultation that they had lately killed and eaten ten of their enemies from the mainland.

About nine, we went ashore near the anchorage. I crossed the island to the village, but did not feel satisfied as to the position. One of our guides to the village wore, as an armlet, the jawbone of a man from the mainland he had killed and eaten; others strutted about with human bones dangling from their hair, and about their necks. It is only the village Tepauri on the mainland with which they are unfriendly. We returned to the boat, and sailed along the coast. On turning a cape, we came to a pretty village, on a well-wooded point. The people were friendly, and led us to see the water, of which there is a good supply. This is the spot for which we have been in search as a station for beginning work. We can go anywhere from here, and are surrounded by villages. The mainland is not more than a gunshot across. God has led us. We made arrangements for a house for the teachers; then returned to the vessel.

In the afternoon, I landed the teachers, their wives, and part of their goods—the people helping to carry the stuff to the house. The house in which the teachers are to reside till our own is finished is the largest in the place, but they can only get the use of one end of it—the owner, who considers himself the chief man of the place, requiring the other end for p. 51himself and family. The partition between the two ends is only two feet high. Skulls, shells, and cocoanuts are hung all about the house; the skulls are those of the enemies he and his people have eaten. Inside the house, hung up on the wall, is a very large collection of human bones, bones of animals and of fish.

I selected a spot for our house on the point of land nearest the mainland. It is a large sand hill, and well wooded at the back. We have a good piece of land, with bread-fruit and other fruit trees on it, which I hope soon to have cleared and planted with food, for the benefit of the teachers who may be here awaiting their stations, as well as for the teacher for the place. The frontage is the Straits, with the mainland right opposite. There is a fine anchorage close to the house for vessels of any size.

Early next morning there was great excitement ashore. The large war canoe came off, with drums beating and men dancing. They came alongside the Bertha, and presented us with a small pig and food. Then the men came on board and danced. The captain gave them a return present. Mr. McFarlane and I went ashore immediately after breakfast, and found that the teachers had been kindly treated. We gave some natives a few axes, who at once set off to cut wood for the house, and before we returned to the vessel in the evening two posts were up. As the Bertha’s time was up, and the season for the trade winds closing, everything was done to get on with p. 52the house. Mr. McFarlane worked well. Two men from the Bertha, and two from the Mayri joined with the four teachers in the work, and by Tuesday the framework was nearly up. We landed our things that day, and immediately after breakfast on Wednesday, December 5th, we went ashore to reside; and about ten a.m. the Bertha left. On the Tuesday, Mr. McFarlane and I visited several villages on the mainland: three in a deep bay, which must be very unhealthy, from the many swamps and high mountains around. The people appeared friendly, and got very excited over the presents we gave them.

We got an old foretopsail from the captain, which we rigged up as a tent, in which the teachers slept, we occupying their quarters. We enjoyed a good night’s rest. In early morning the house was surrounded with natives, many of whom were armed. They must wonder at our staying here: they consider our goods to consist entirely of hoop-iron, axes, knives, and arrowroot. About eleven a.m. the war canoes were launched on the opposite side of the water. The excitement here was then great. I met a lad running with painted skulls to the war canoe of the village. Soon it was decorated with skulls, shells, cocoanuts, and streamers, and launched. Those on the opposite side came out into the deep bay; ours remained stationary till the afternoon, when about thirty men got into her, and away towards Farm Bay to trade their hoop-iron for sago.

p. 53On Sunday, we met for our usual public services under a large tree, and a number of natives attended, who of course could not make out what was said, as they were conducted in Rarotongan. At our morning and evening prayers numbers are always about who seem to enjoy the singing. We see quite a number of strangers every day—some from Brumer Island, Tissot, Teste, China Straits, Catamaran Bay, Farm Bay, and other places. Those from Vakavaka—a place over by China Straits—are lighter and better-looking than those here. The women there do not seem to tattoo themselves. Here they tattoo themselves all over their faces and bodies, and make themselves look very ugly. I have not seen one large man or woman amongst them all.

We had much difficulty in getting a sufficient supply of plaited cocoanut leaves for the walls and roof of our house. By the 14th, we had the walls and roof finished, when all our party moved into it. We had a curtain of unbleached calico put up between the teachers’ end and ours, and curtains for doors and windows, but were glad to get into it in that unfinished state: the weather was breaking, and we felt anxious about the teachers sleeping in the tent when it rained, and we had no privacy at all where we were, and were tired of squatting on the ground, for we could not get a chair in our part of the house; indeed, the flooring was of such a construction that the legs of a chair or table would have p. 54soon gone through it. On the 13th, we were busy getting the wood we had cut for the flooring of our house into the sea to be rafted along; got ten large pieces into the water by breakfast-time.

After breakfast, Mrs. Chalmers and I were at the new house, with the captain of the Mayri, when we heard a noise like quarrelling. On looking out, I saw the natives very excited, and many of them running with spears and clubs towards the house where Mrs. Chalmers, about five minutes before, had left the teachers rising from breakfast. I hastened over, and pushed my way amongst the natives till I got to the front, when, to my horror, I was right in front of a gun aimed by one of the Mayri’s crew (who had been helping us with the house) at a young man brandishing a spear. The aim was perfect: had the gun been fired—as it would have been had I not arrived in time—the native would have been shot dead. I pushed the native aside, and ordered the gun to be put down, and turned to the natives, shouting, Besi, besi! (Enough, enough!). Some of them returned their spears and clubs, but others remained threatening. I spoke to our party against using firearms, and then I caught the youth who was flourishing his spear, and with difficulty got it from him. Poor fellow, he cried with rage, yet he did me no harm. I clapped him, and got him to go away. All day he sat under a tree, which we had frequently to pass, but he would have nothing to say to us. It seems a knife p. 55had been stolen, and he being the only one about the house when it was missed, was accused of taking it. One of the teachers was winding line, and he caught the young fellow by the arm to inquire about the knife. The lad thought he was going to be tied up with the line; he struggled, got free, and raised the alarm.

Only the night before I had to warn the teachers against using firearms to alarm or threaten the natives. An axe was stolen; every place about was searched for it, and for some time without its being found. At last, a native found it buried in the sand near where it was last used. It had evidently been hidden there till a favourable opportunity should occur of taking it away. During the search, the owner of the axe (one of the teachers) ran off for his gun, and came rushing over with it. I ordered him to take it back, and in the evening told them it was only in New Guinea that guns were used by missionaries. It was not so in any other mission I knew of, and if we could not live amongst the natives without arms, we had better remain at home; and if I saw arms used again by them for anything, except birds, or the like, I should have the whole of them thrown into the sea.

In the afternoon of the 14th, I went over to the house in which we had been staying, to stir up the teachers to get the things over more quickly; Mrs. Chalmers remaining at the new house to look after the things there, as, without doors or flooring, everything p. 56was exposed. I went to the seaside to call to the captain of the Mayri to send us the boat ashore, when, on looking towards my left, I saw twenty armed natives hurrying along. Though painted, I recognized some of them as those who were very friendly on board the Bertha, and spoke to them; but they hurried past, frowning and saying something I did not understand. They went straight on to the chief’s house, and surrounded our party. I passed through, and stood in front of them. One very ugly-looking customer was brandishing his spear close by me. It was an anxious moment, and one in which I am sure many would have used firearms. I called out to the teachers, “Remain quiet.” Our chief sprung out on to the platform in front of the house and harangued. He was very excited. Shortly he called to the teachers, in signs and words, to bring out their guns and fire. They refused. He then rushed into the house and seized a gun, and was making off with it, when one of the teachers caught hold of him. I, seeing the teacher with the chief, thought something was wrong, and went to them. We quieted him, and did our best to explain to him that we were no fighters, but men of peace. The babel all round us was terrible. By-and-by a request was made to me to give the chief from the other side a present, and get him away. I said, “No; had he come in peace, and as a chief, I would have given him a present, but I will not do so now.” They retired to deliberate, and sent p. 57another request for a present. “No; no presents to men in arms. If the chief returns to-morrow unarmed, he will get a present.” It seems they are vexed with our living here instead of with them, because they find those here are getting what they consider very rich by our living with them. When quiet was restored, we returned to the carrying of our things. When we came to the last few things, our chief objected to their removal until he got a farewell present. He had been paid for the use of the house before any of us entered it; but we gave him another present, and so finished the business.

Our large cross-cut saw was stolen during the hubbub. It belonged to the teachers of East Cape. It had only been lent to us, so we had to get it back. The next morning the chief from the other side came to see me. He received a present, and looked particularly sheepish when I tried to explain to him that we did not like fighting. All day I took care to show that I was very displeased at the loss of the saw, and by the evening I was told that it had been taken by those on the other side; and offers of returning it were made, but I saw I was expected to buy it from them. I said, “No; I will not buy what was stolen from me; the saw must be returned, and I will give an axe to the one who goes for it, and fetches it to me.”

The following day, Sunday, the 15th, we held the usual services under a large tree near the mission house; a great many strangers present; the latter were p. 58very troublesome. On Monday afternoon the saw was returned. The Mayri left us that day, to visit the teachers at East Cape. The people are getting quieter. At present they are chiefly interested in the sawing of the wood for the flooring of the house. They work willingly for a piece of hoop-iron and a few beads, but cannot do much continuously. They seem to have no kind of worship, and their sports are few. The children swing, bathe, and sail small canoes. The grown-up people have their dance—a very poor sort of thing. A band of youths, with drums, stand close together, and in a most monotonous tone sing whilst they beat the drums. The dancers dance round the men once or twice, and all stop to rest a bit. I have been twice present when only the women danced. They bury their dead, and place houses over the graves, which they fence round, planting crotons, bananas, etc., inside. They do their cooking inside their houses. It was very hot and uncomfortable when we were in the native house. The master being a sort of chief, and having a large household, a great deal of cooking was required. Three large fires were generally burning in their end of the house for the greater part of the day. The heat and smoke from these fires were not nice. Indeed, they generally had one or two burning all night, to serve for blankets, I suppose.

We went on with our work about the place, getting on well with the natives and with those from other parts. We became so friendly with the natives that I p. 61had hoped to go about with them in their canoes. Several natives from one of the settlements invited me to visit their place, and said if I went with them in their canoe they would return me. I went with them, and was well received by all the people at the settlement, where I spent some hours. On the 21st of December, the Mayri returned from East Cape, and reported that all were sick, but that the people were very friendly and kind to teachers. Anxious to keep the vessel employed, and to prepare the way for landing teachers, I resolved to visit a settlement on the mainland at deadly feud with this people. The people here tried hard to dissuade me from going, telling me that, as I stayed with them, my head would be cut off. Seeing me determined to go, they brought skulls, saying, mine would be like that, to adorn their enemies’ war canoe, or hang outside the chief’s house. Feeling sure that they did not wish me to go because they were afraid the hoop-iron, the knives, axes, beads, and cloth might also be distributed on the other side, I told them I must go; so they left me to my fate.

I took the teacher with me that I hoped to leave there. We were received very kindly by the people. They led us inland, to show us there was water, and when we got back to the seaside they regaled us with sugar-cane and cocoanuts. They then told us that they did not live at the village, but at the next, and merely came here for food. We then got into a canoe, and were paddled up to the other village, where a great p. 62crowd assembled, and where we publicly gave the chiefs our presents. They danced with delight, and told the teacher not to be long until he came to reside with them.

On our return we thought our friends seemed disappointed. We had suffered no harm; however, as I had been unwell for some days, and felt worse on the day following my trip, they felt comforted, and assured me it was because of our visiting Tepauri. We had several things stolen, and amongst other things a camp oven, which we miss much. Yet these are things which must be borne, and we can hope that some day their stealing propensities will change. From a very unexpected source, and in a very unexpected manner, the whole prospects of this eastern mission seemed all at once to be upset. I do not think I can do better than extract my journal for the next few days.

December 29th.—About twelve o’clock three lads from the Mayri came ashore to cut firewood. One of them came to me, saying, “I ’fraid, sir, our captain he too fast with natives. One big fellow he come on board, and he sit down below. Captain he tell him get up; he no get up. Captain he get sword, and he tell him, s’pose he no get up he cut head off; he get up, go ashore. I fear he no all right.” They left me and went towards the sawpit. Some men were clearing at the back of my house, some were putting up a cook-house, and the teachers were sawing wood. On the cook-house being finished, I was paying the men, when, on p. 63hearing a great noise, I rose up and saw those who were at the sawpit running away and leaping the fence, and heard firing as if from the vessel. I rushed into the house with my bag, and then out to see what it was. I saw natives on board the Mayri, and some in canoes; they were getting the hawser ashore, and pulling up the anchor, no doubt to take the vessel. Everywhere natives were appearing, some armed, and others unarmed. Two of the lads from the vessel, wishing to get on board, went to their boat, but found the natives would not let it go. I shouted to the natives detaining it to let it go, which they did. Had I not been near, they would certainly have been fired upon by the two lads, who were armed with muskets. Before the boat got to the vessel I saw natives jump overboard, and soon the firing became brisker. I rushed along the beach, calling upon the natives to get into the bush, and to those on board to cease firing. Firing ceased, and soon I heard great wailing at the chief’s house, where I was pressed to go. A man was shot through the leg and arm. On running through the village to the house, to get something for the wounded man, I was stopped to see a young man bleeding profusely, shot through the left arm, the bullet entering the chest. I got some medicine and applied it to both.

When I reached the house, I found Mrs. Chalmers the only calm person there. Natives were all around armed. When at the chief’s house with medicine I was told there was still another, and he was on board. p. 64They kept shouting “Bocasi, Bocasi,” the name of the man who was on board in the morning. I found a small canoe all over blood, and two natives paddled me off. On getting alongside, I saw the captain sitting on deck, looking very white, and blood all about him. I asked, “Is there still a man on board?” Answer: “Yes.” “Is he shot?” “Yes.” “Dead?” “Yes.” He was dead, and lying below. I was afraid to remain long on board, and would not risk landing with the body; nor would it do for the body to be landed before me, as then I might be prevented from landing at all; so I got into the canoe, in which one native was sitting. The other was getting the body to place in the canoe; but I said, “Not in this one, but a larger one.” So ashore I went, and hastened to the house. I understood the captain to say that they attempted to take his life, and this big man, armed with a large sugar-cane knife, was coming close up, and he shot him dead. The captain’s foot was frightfully cut. He had a spear-head in his side, and several other wounds.

The principal people seemed friendly, and kept assuring us that all was right, we should not be harmed. Great was the wailing when the body was landed, and arms were up and down pretty frequently. Canoes began to crowd in from the regions around. A man who has all along been very friendly and kept close by us advised us strongly to leave during the night, as, assuredly, when the war canoes from the p. 65different parts came in, we should be murdered. Mrs. Chalmers decidedly opposed our leaving. God would protect us. The vessel was too small, and not provisioned, and to leave would be losing our position as well as endangering Teste and East Cape. We came here for Christ’s work, and He would protect us.