| Main Index | Previous Part |

CHAPTER VII—TEMPLES AND TOMBS OF THEBES

CHAPTER VIII—THE ASSYRIAN AND NEO-BABYLONIAN EMPIRES IN THE LIGHT OF

CHAPTER IX—THE LAST DAYS OF ANCIENT EGYPT

324.jpg XIth Dynasty Wall: Dêr El-bahari.

325.jpg XVIIIth Dynasty Wall, Dbr El-bahari.

326.jpg Excavation of the North Lower Colonnade Of The XIth Dynasty Temple, Der El-bahari, 1904.

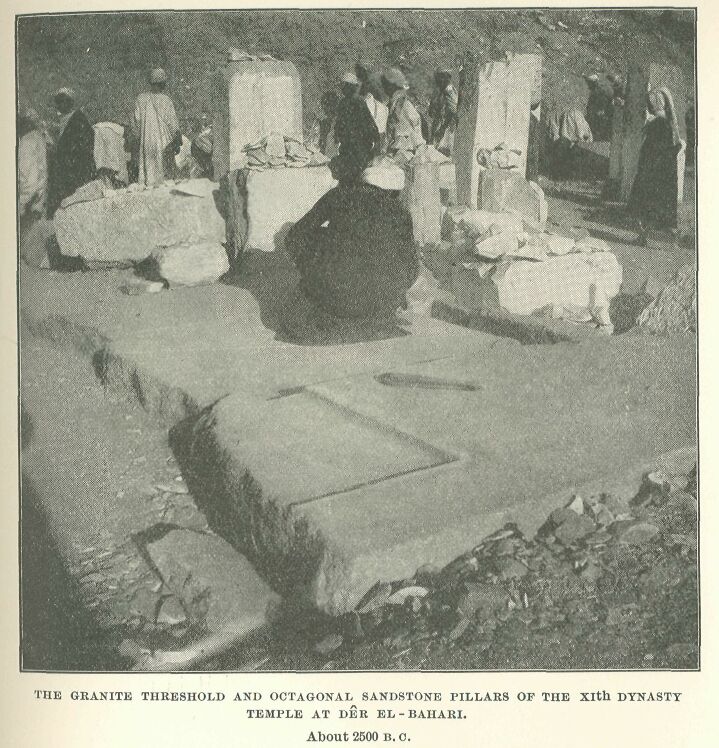

327.jpg Granite Threshold and Octagonal Sandstone Pillars

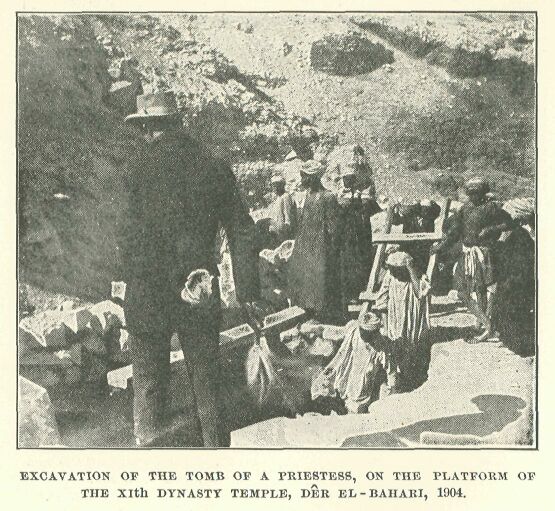

328.jpg Excavation of the Tomb Of a Priestess,

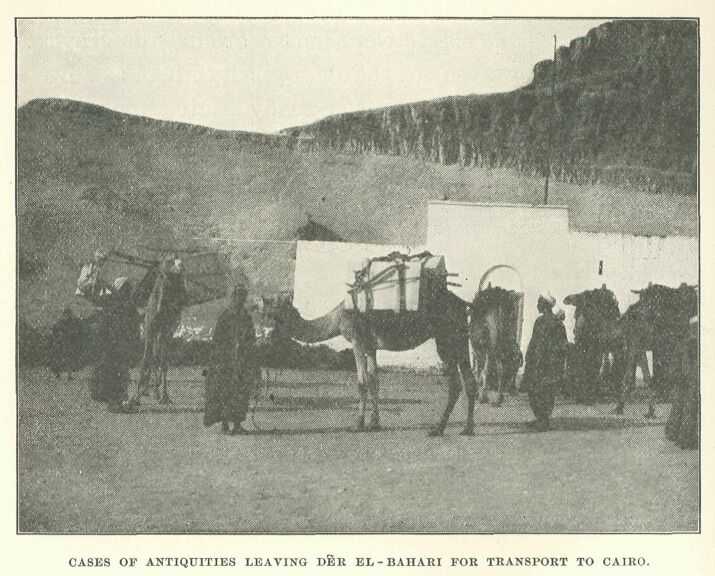

330.jpg Cases of Antiquities Leaving Dêr El-bahari For Transport to Cairo.

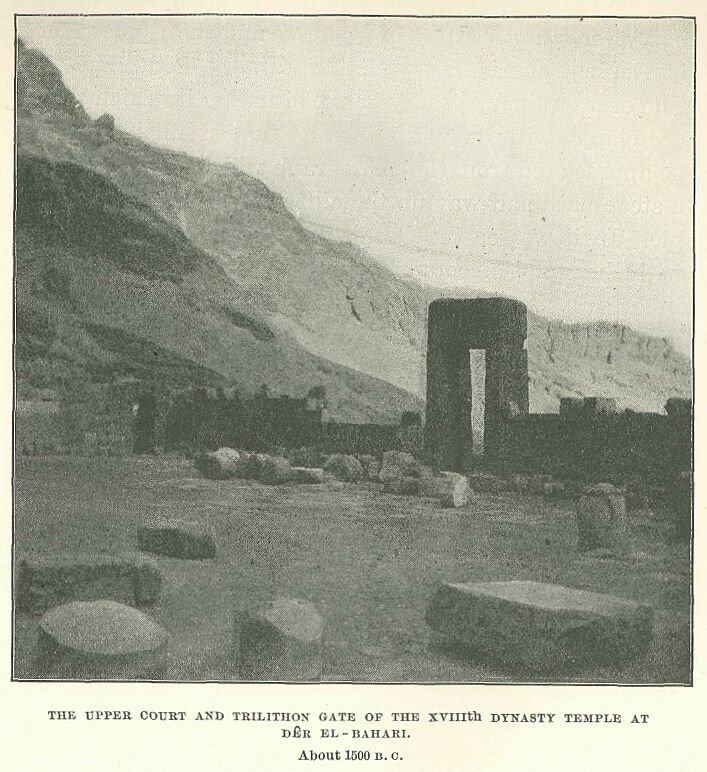

338.jpg Statue of Queen Teta-shera

346.jpg the Upper Court and Trilithon Gate

350.jpg the Tomb-mountain of Amenhetef III, in The Western Valley, Thebes.

356.jpg the Tomb-hill of Shekh 'abd El-kubna, Thebes.

358.jpg Wall-painting from a Tomb

360.jpg Fresco in the Tomb of Senmut at Thebes. About 1500 B.C.

368.jpg Page Image to Display Greek Words

369.jpg Page Image to Display Greek Words

372.jpg the Valley of The Tombs Of The Queens at Thebes.

374.jpg the Nile-bank at Luxor

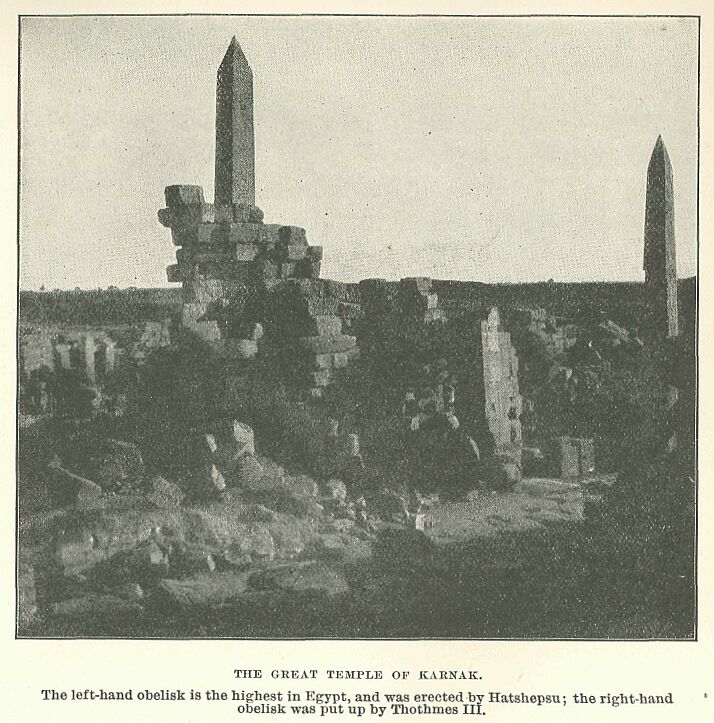

376.jpg the Great Temple Of Kaknak.

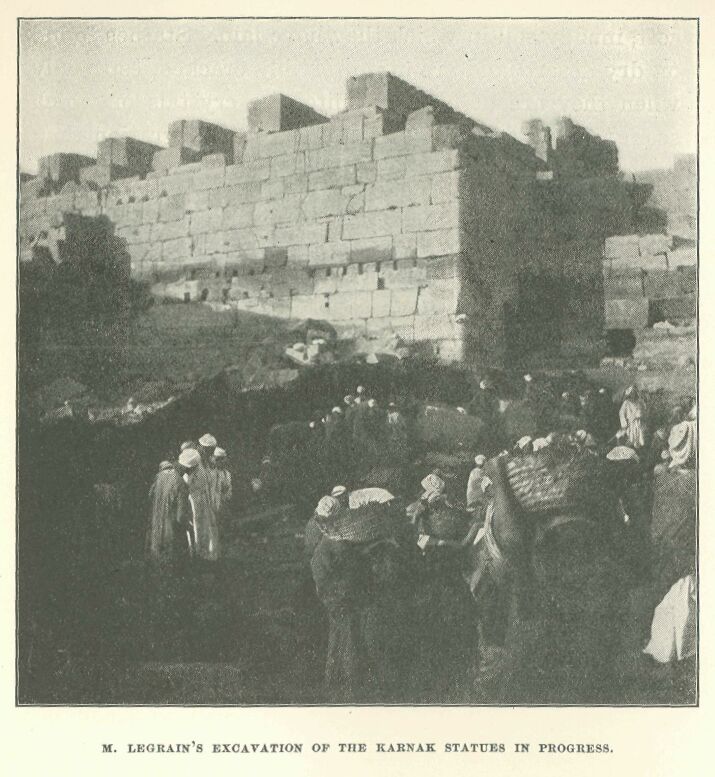

379.jpg the Great Temple Of Kaknak.

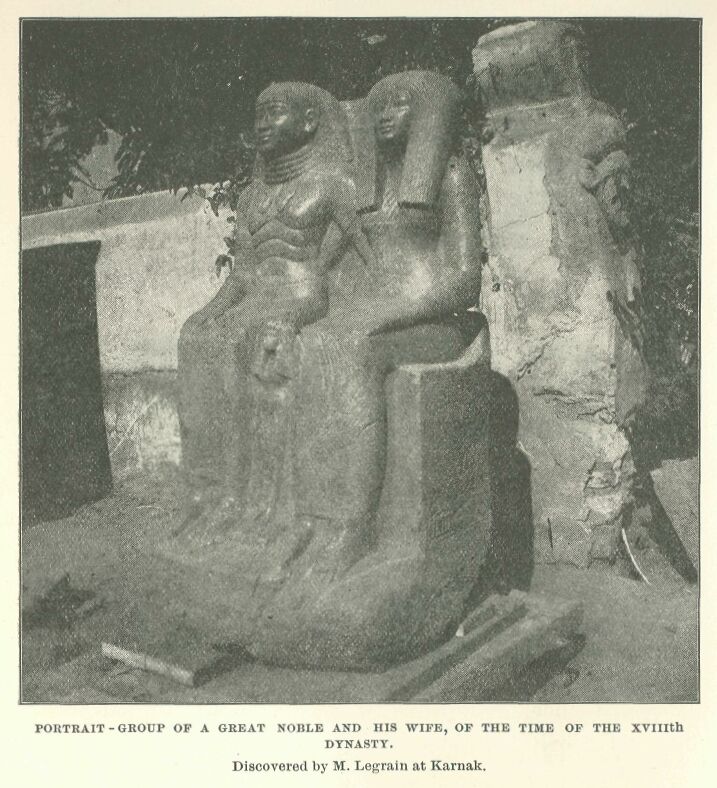

381.jpg Portrait-group of a Great Noble and his Wife

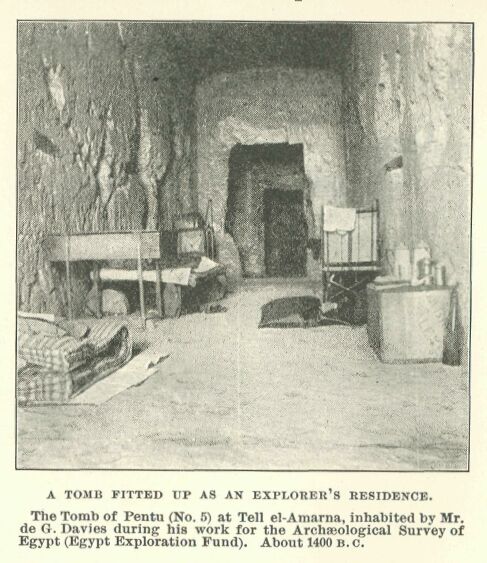

382.jpg a Tomb Fitted up As an Explorer's Residence.

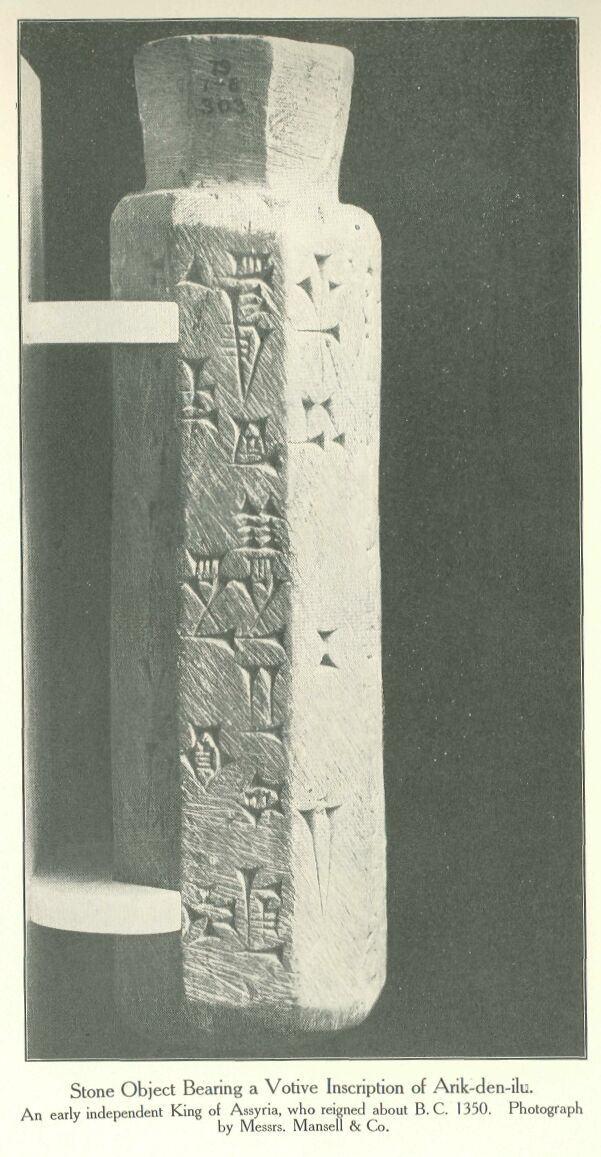

396.jpg Stone Object Bearing a Votive Inscription Of Arik-den-ilu.

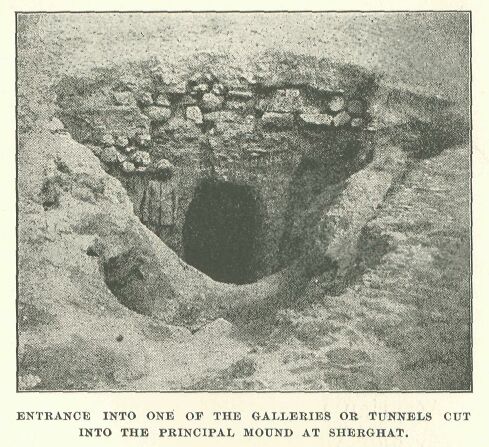

397.jpg Entrance Into One of the Galleries Or Tunnels Cut Into the Principal Mound at Sherghat.

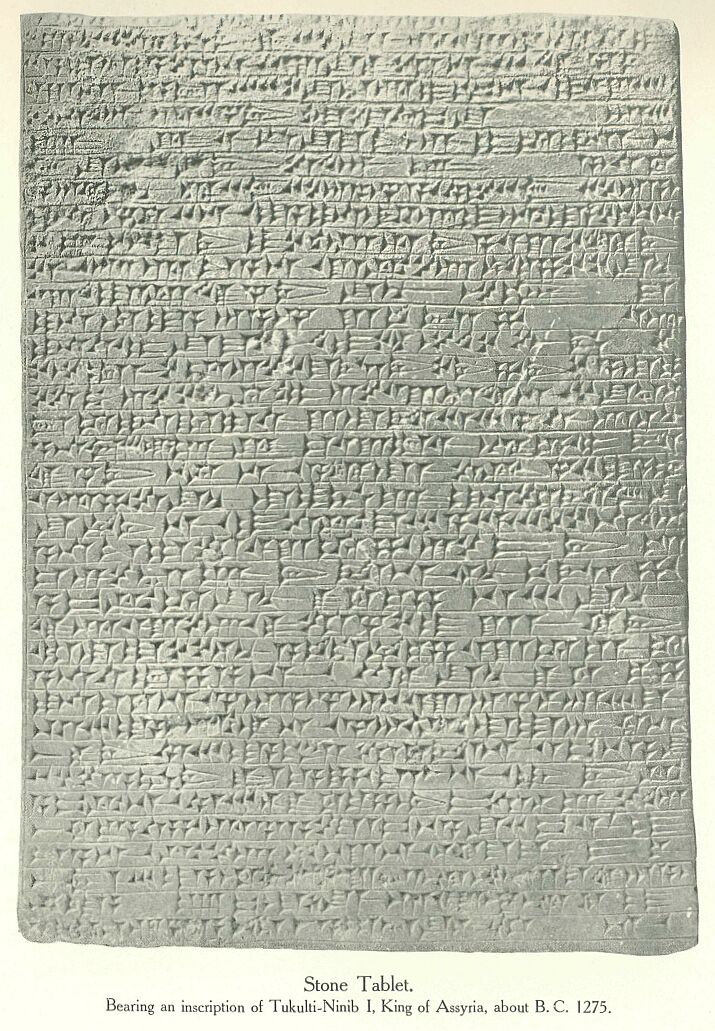

408.jpg Stone Tablet. Bearing an Inscription Of Tukulti-ninib I

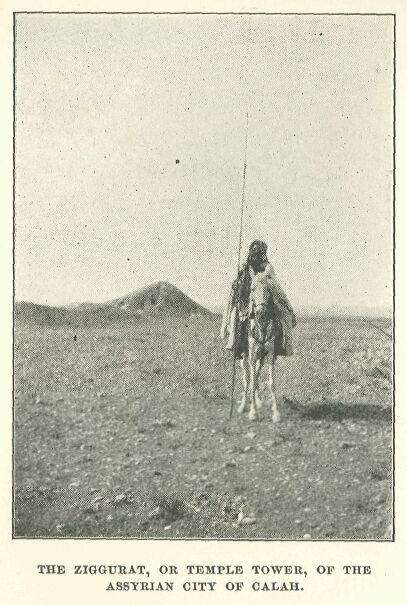

410.jpg the Ziggurat, Or Temple Tower, of The Assyrian City of Calah.

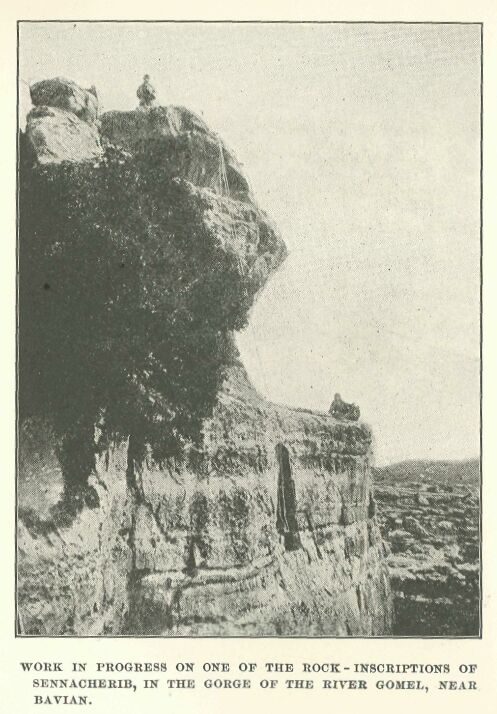

413.jpg Work in Progress on One of the Rock-inscriptions Of Sennacherib

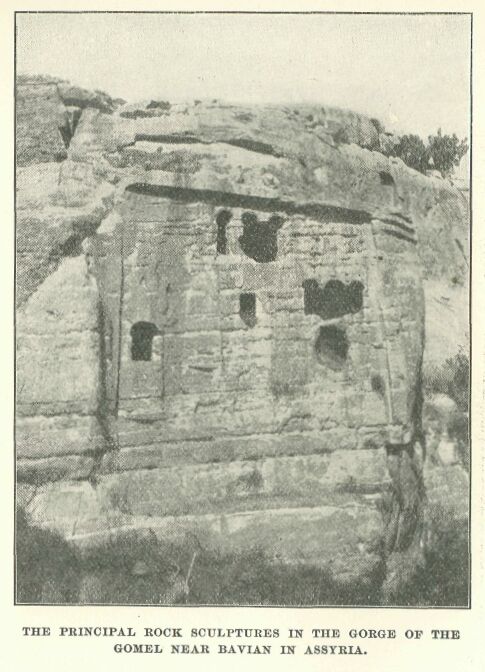

414.jpg the Principal Rock Sculptures in The Gorge of The Gomel

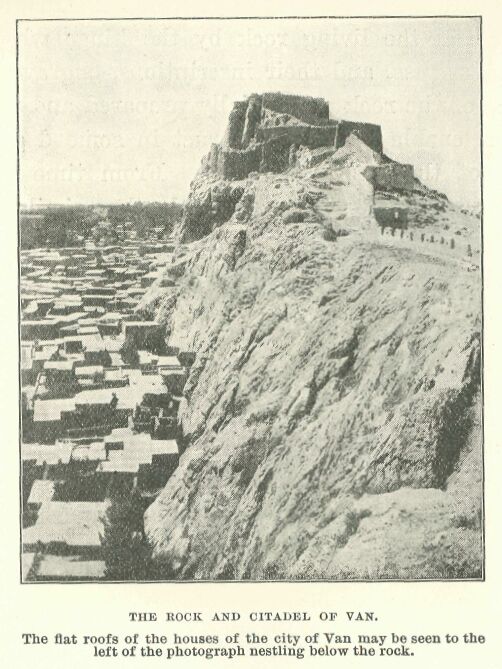

415.jpg the Rock and Citadel of Van.

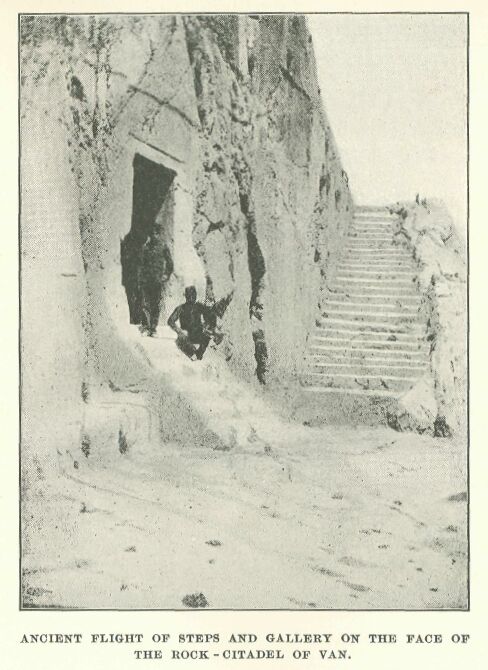

417.jpg Ancient Flight of Steps and Gallery on the Face Of the Rock-citadel of Van.

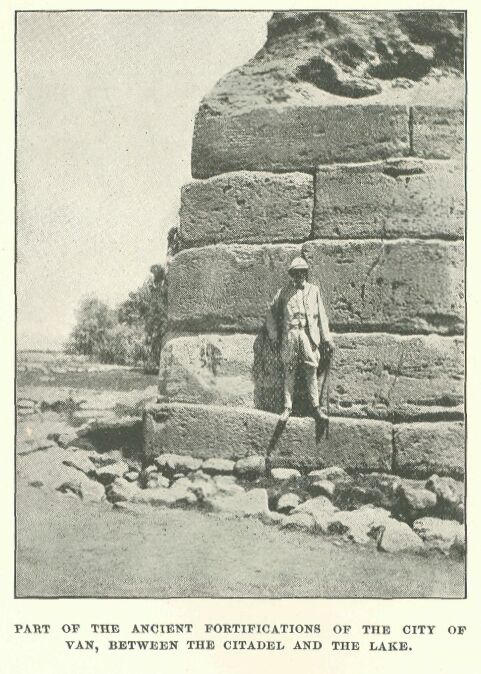

419.jpg Part of the Ancient Fortifications Of The City Of Van, Between the Citadel and The Lake.

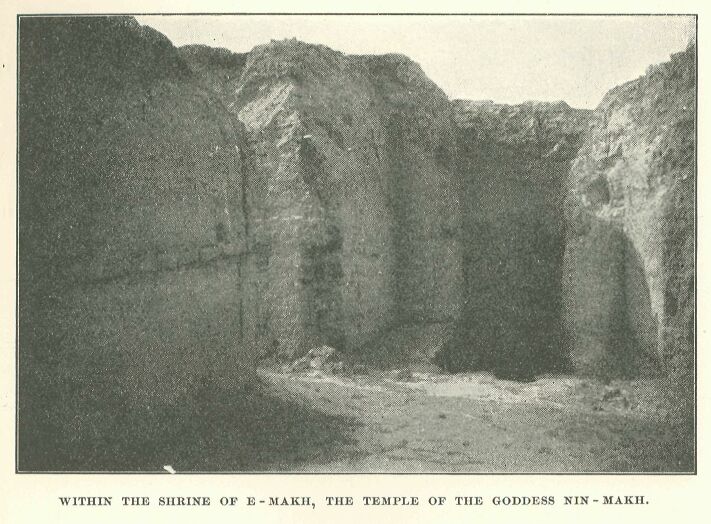

425.jpg Within the Shrine Of E-makh, The Temple Of The Goddess Nin-makh.

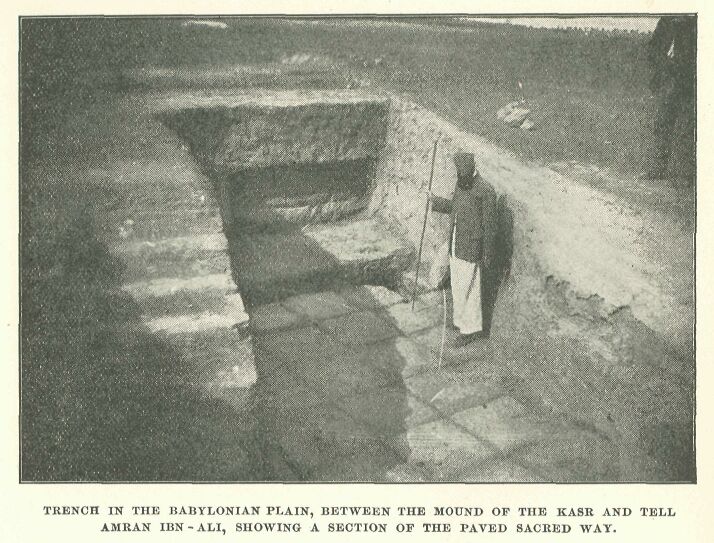

426.jpg Trench in the Babylonian Plain

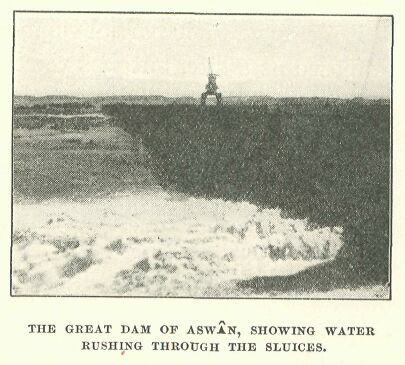

447.jpg the Great Dam of Aswan

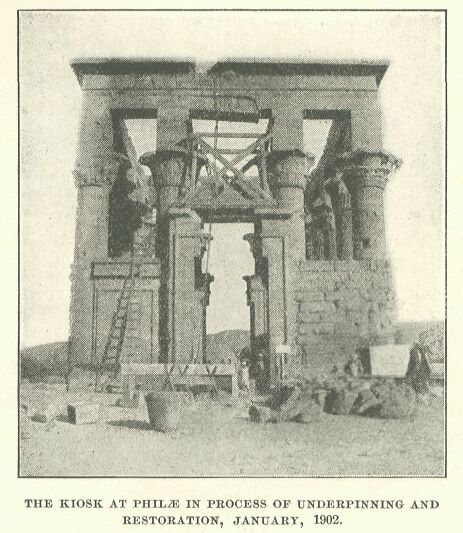

449.jpg the Kiosk at Philae in Process of Underpinning And Restoration, January, 1902.

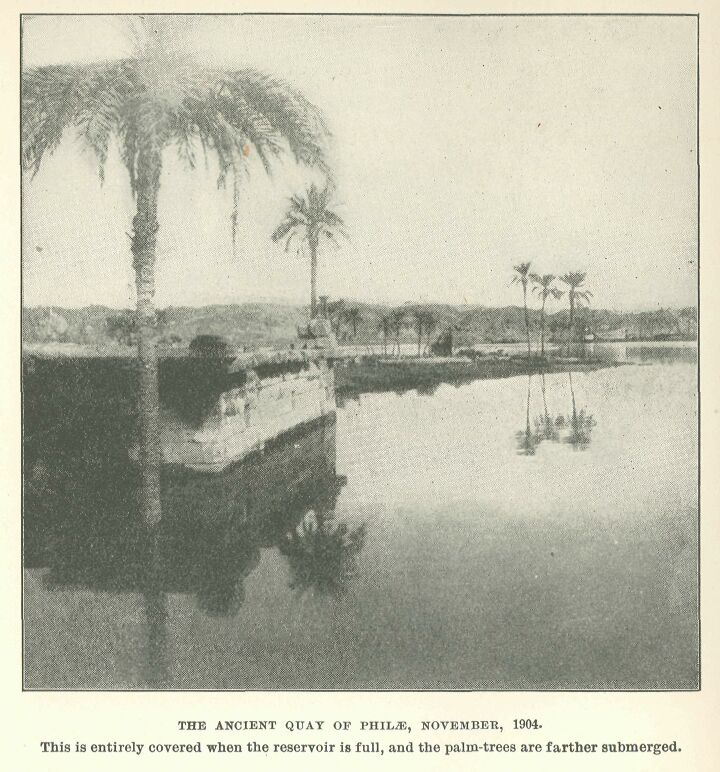

450.jpg the Ancient Quay Of PhilÆ, November, 1904.

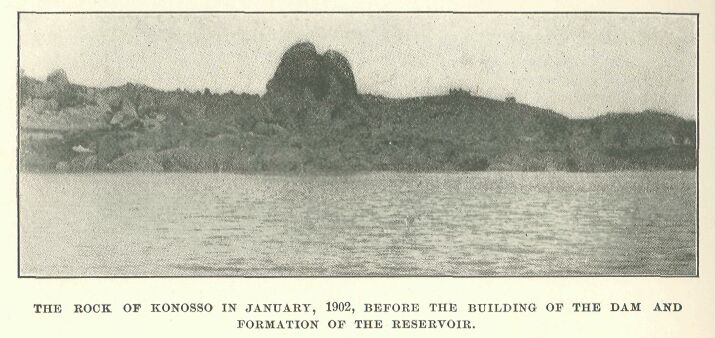

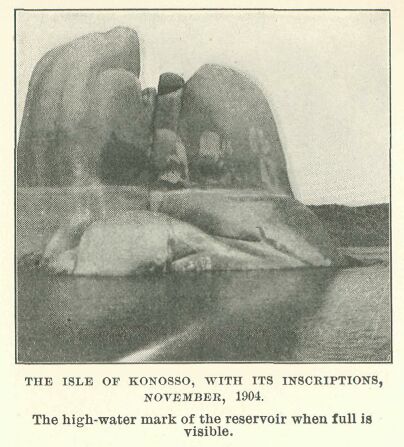

454.jpg the Isle of Konosso, With Its Inscriptions

We have seen that it was in the Theban period that Egypt emerged from her isolation, and for the first time came into contact with Western Asia. This grand turning-point in Egyptian history seemed to be the appropriate place at which to pause in the description of our latest knowledge of Egyptian history, in order to make known the results of archaeological discovery in Mesopotamia and Western Asia generally. The description has been carried down past the point of convergence of the two originally isolated paths of Egyptian and Babylonian civilization, and what new information the latest discoveries have communicated to us on this subject has been told in the preceding chapters. We now have to retrace our steps to the point where we left Egyptian history and resume the thread of our Egyptian narrative.

The Hyksos conquest and the rise of Thebes are practically contemporaneous. The conquest took place perhaps three or four hundred years after the first advancement of Thebes to the position of capital of Egypt, but it must be remembered that this position was not retained during the time of the XIIth Dynasty. The kings of that dynasty, though they were Thebans, did not reign at Thebes. Their royal city was in the North, in the neighbourhood of Lisht and Mêdûm, where their pyramids were erected, and their chief care was for the lake province of the Fayyûm, which was largely the creation of Amenemhat III, the Moeris of the Greeks. It was not till Thebes became the focus of the national resistance to the Hyksos that its period of greatness began. Henceforward it was the undisputed capital of Egypt, enlarged and embellished by the care and munificence of a hundred kings, enriched by the tribute of a hundred conquered nations.

But were we to confine ourselves to the consideration only of the latest discoveries of Theban greatness after the expulsion of the Hyksos, we should be omitting much that is of interest and importance. For the Egyptians the first grand climacteric in their history (after the foundation of the monarchy) was the transference of the royal power from Memphis and Herakleopolis to a Theban house. The second, which followed soon after, was the Hyksos invasion. The two are closely connected in Theban history; it is Thebes that defeated Herakleopolis and conquered Memphis; it is Theban power that was overthrown by the Hyksos; it is Thebes that expelled them and initiated the second great period of Egyptian history. We therefore resume our narrative at a point before the great increase of Theban power at the time of the expulsion of the Hyksos, and will trace this power from its rise, which followed the defeat of Herakleopolis and Memphis. It is upon this epoch—the beginning of Theban power—that the latest discoveries at Thebes have thrown some new light.

More than anywhere else in Egypt excavations have been carried on at Thebes, on the site of the ancient capital of the country. And here, if anywhere, it might have been supposed that there was nothing more to be found, no new thing to be exhumed from the soil, no new fact to be added to our knowledge of Egyptian history. Yet here, no less than at Abydos, has the archaeological exploration of the last few years been especially successful, and we have seen that the ancient city of Thebes has a great deal more to tell us than we had expected.

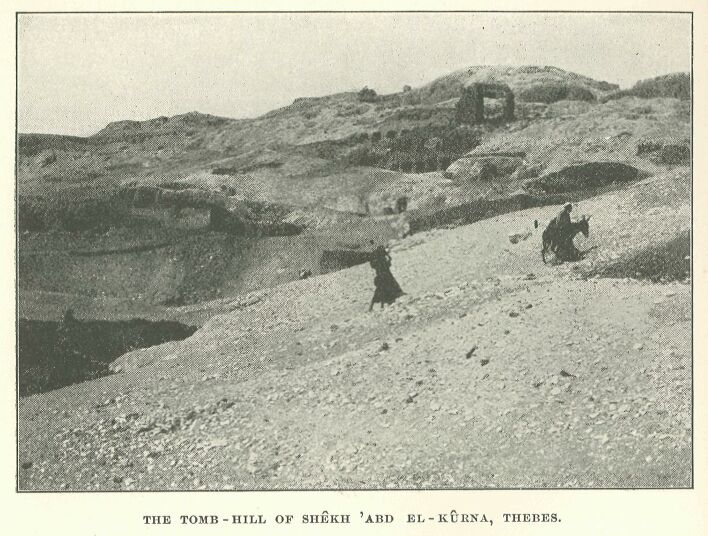

The most ancient remains at Thebes were discovered by Mr. Newberry in the shape of two tombs of the VIth Dynasty, cut upon the face of the well-known hill of Shêkh Abd el-Kûrna, on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor. Every winter traveller to Egypt knows, well the ride from the sandy shore opposite the Luxor temple, along the narrow pathway between the gardens and the canal, across the bridges and over the cultivated land to the Ramesseum, behind which rises Shêkh Abd el-Kûrna, with its countless tombs, ranged in serried rows along the scarred and scarped face of the hill. This hill, which is geologically a fragment of the plateau behind which some gigantic landslip was sent sliding in the direction of the river, leaving the picturesque gorge and cliffs of Dêr el-Bahari to mark the place from which it was riven, was evidently the seat of the oldest Theban necropolis. Here were the tombs of the Theban chiefs in the period of the Old Kingdom, two of which have been found by Mr. Newberry. In later times, it would seem, these tombs were largely occupied and remodelled by the great nobles of the XVIIIth Dynasty, so that now nearly all the tombs extant on Shêkh Abd el-Kûrna belong to that dynasty.

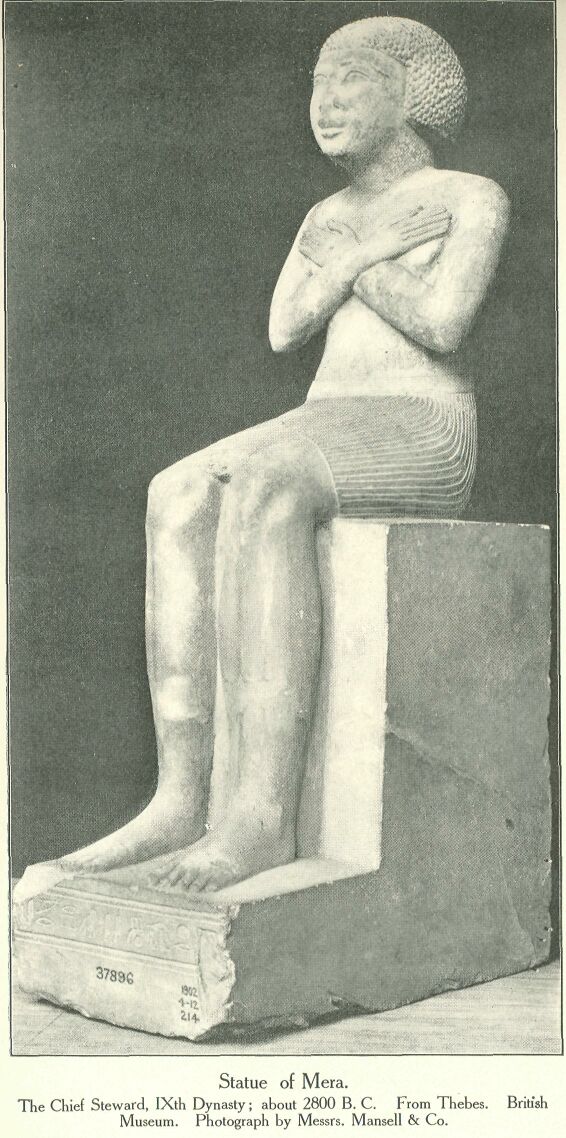

Of the Thebes of the IXth and Xth Dynasties, when the Herakleopolites ruled, we have in the British Museum two very remarkable statues—one of which is here illustrated—of the steward of the palace, Mera. The tomb from which they came is not known. Both are very beautiful examples of the Egyptian sculptor's art, and are executed in a style eminently characteristic of the transition period between the work of the Old and Middle Kingdoms. As specimens of the art of the Hierakonpolite period, of which we have hardly any examples, they are of the greatest interest. Mera is represented wearing a different head-dress in each figure; in one he has a short wig, in the other a skullcap.

When the Herakleopolite dominion was finally overthrown, in spite of the valiant resistance of the princes of Asyût, and the Thebans assumed the Pharaonic dignity, thus founding the XIth Dynasty, the Theban necropolis was situated in the great bay in the cliffs, immediately north of Shêkh Abd el-Kûrna, which is known as Dêr el-Bahari. In this picturesque part of Western Thebes, in many respects perhaps the most picturesque place in Egypt, the greatest king of the XIth Dynasty, Neb-hapet-Râ Mentuhetep, excavated his tomb and built for the worship of his ghost a funerary temple, which he called Akh-aset, "Glorious-is-its- Situation," a name fully justified by its surroundings. This temple is an entirely new discovery, made by Prof. Naville and Mr. Hall in 1903. The results obtained up to date have been of very great importance, especially with regard to the history of Egyptian art and architecture, for our sources of information were few and we were previously not very well informed as to the condition of art in the time of the XIth Dynasty.

The new temple lies immediately to the south of the great XVIIIth Dynasty temple at Dêr el-Bahari, which has always been known, and which was excavated first by Mariette and later by Prof. Naville, for the Egypt Exploration Fund. To the results of the later excavations we shall return. When they were finally completed, in the year 1898, the great XVIIIth Dynasty temple, which was built by Queen Hatshepsu, had been entirely cleared of débris, and the colonnades had been partially restored (under the care of Mr. Somers Clarke) in order to make a roof under which to protect the sculptures on the walls. The whole mass of débris, consisting largely of fallen talus from the cliffs above, which had almost hidden the temple, was removed; but a large tract lying to the south of the temple, which was also covered with similar mounds of débris, was not touched, but remained to await further investigation. It was here, beneath these heaps of débris, that the new temple was found when work was resumed by the Egypt Exploration Fund in 1903. The actual tomb of the king has not yet been revealed, although that of Neb-hetep Mentuhetep, who may have been his immediate predecessor, was discovered by Mr. Carter in 1899. It was known, however, and still uninjured in the reign of Ramses IX of the XXth Dynasty. Then, as we learn from the report of the inspectors sent to examine the royal tombs, which is preserved in the Abbott Papyrus, they found the pyramid-tomb of King Xeb-hapet-Râ which is in Tjesret (the ancient Egyptian name for Dêr el-Bahari); it was intact. We know, therefore, that it was intact about 1000 B.C. The description of it as a pyramid-tomb is interesting, for in the inscription of Tetu, the priest of Akh-aset, who was buried at Abydos, Akh-aset is said to have been a pyramid. That the newly discovered temple was called Akh-aset we know from several inscriptions found in it. And the most remarkable thing about this temple is that in its centre there was a pyramid. This must be the pyramid-tomb which was found intact by the inspectors, so that the tomb itself must be close by. But it does not seem to have been beneath the pyramid, below which is only solid rock. It is perhaps a gallery cut in the cliffs at the back of the temple.

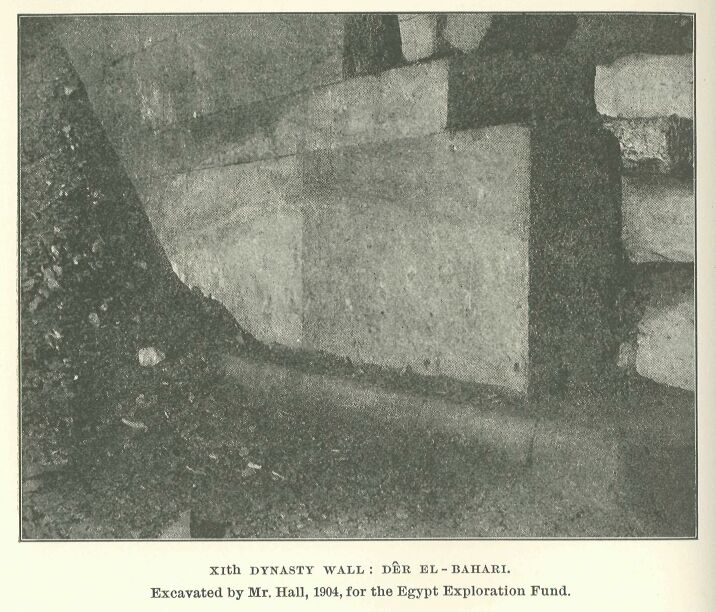

The pyramid was then a dummy, made of rubble within a revetment of heavy flint nodules, which was faced with fine limestone. It was erected on a pyloni-form base with heavy cornice of the usual Egyptian pattern. This central pyramid was surrounded by a roofed hall or ambulatory of small octagonal pillars, the outside wall of which was decorated with coloured reliefs, depicting various scenes connected with the sed-heb or jubilee-festival of the king, processions of the warriors and magnates of the realm, scenes of husbandry, boat-building, and so forth, all of which were considered appropriate to the chapel of a royal tomb at that period. Outside this wall was an open colonnade of square pillars. The whole of this was built upon an artificially squared rectangular platform of natural rock, about fifteen feet high. To north and south of this were open courts. The southern is bounded by the hill; the northern is now bounded by the Great Temple of Hat-shepsu, but, before this was built, there was evidently a very large open court here. The face of the rock platform is masked by a wall of large rectangular blocks of fine white limestone, some of which measure six feet by three feet six inches. They are beautifully squared and laid in bonded courses of alternate sizes, and the walls generally may be said to be among the finest yet found in Egypt. We have already remarked that the architects of the Middle Kingdom appear to have been specially fond of fine masonry in white stone. The contrast between these splendid XIth Dynasty walls, with their great base-stones of sandstone, and the bad rough masonry of the XVIIIth Dynasty temple close by, is striking. The XVIIIth Dynasty architects and masons had degenerated considerably from the standard of the Middle Kingdom.

This rock platform was approached from the east in the centre by an inclined plane or ramp, of which part of the original pavement of wooden beams remains in situ.

Excavated by Mr. Hall, 1904, for the Egypt Exploration Fund.

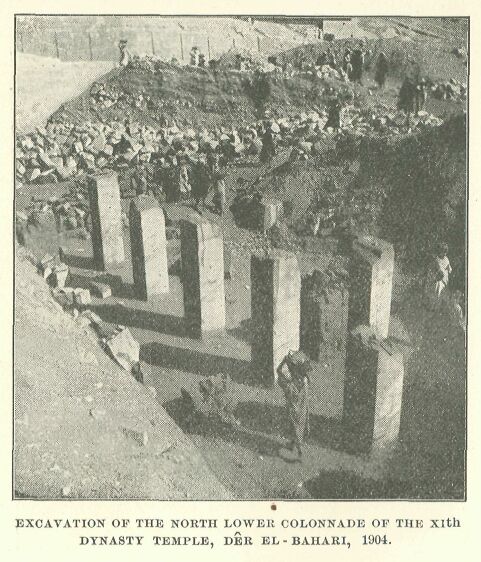

To right and left of this ramp are colonnades, each of twenty-two square pillars, all inscribed with the name and titles of Mentuhetep. The walls masking the platform in these colonnades were sculptured with various scenes, chiefly representing boat processions and campaigns against the Aamu or nomads of the Sinaitic peninsula. The design of the colonnades is the same as that of the Great Temple, and the whole plan of this part, with its platform approached by a ramp flanked by colonnades, is so like that of the Great Temple that we cannot but assume that the peculiar design of the latter, with its tiers of platforms approached by ramps flanked by colonnades, is not an original idea, but was directly copied by the XVIIIth Dynasty architects from the older XIth Dynasty temple which they found at Dêr el-Bahari when they began their work.

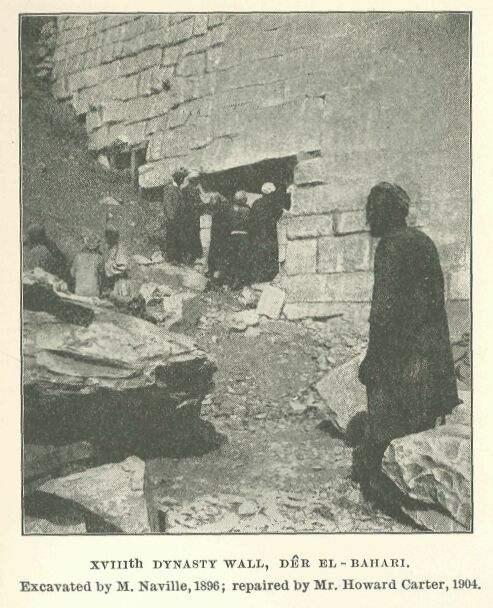

Excavated by M. Naville, 1896; repaired by Mr. Howard

Carter, 1904.

The supposed originality of Hatshepsu's temple is then non-existent; it was a copy of the older design, in fact, a magnificent piece of archaism. But Hatshepsu's architects copied this feature only; the actual arrangements on the platforms in the two temples are as different as they can possibly be. In the older we have a central pyramid with a colonnade round it, in the newer may be found an open court in front of rock-cave shrines.

Before the XIth Dynasty temple was set up a series of statues of King Mentuhetep and of a later king, Amenhetep I, in the form of Osiris, like those of Usertsen (Senusret) I at Lisht already mentioned. One of these statues is in the British Museum. In the south court were discovered six statues of King Usertsen (Senusret) III, depicting him at different periods of his life. Pour of the heads are preserved, and, as the expression of each differs from that of the other, it is quite evident that some show him as a young, others as an old, man.

Of The XIth Dynasty Temple At Dee El-Bahari. About 2500 B.C.

The face is of the well-known hard and lined type which is seen also in the portraits of Amenemhat III, and was formerly considered to be that of the Hyksos. Messrs. Newberry and Garstang, as we have seen, consider it to be so, indirectly, as they regard the type as having been introduced into the XIIth Dynasty by Queen Nefret, the mother of Usertsen (Sen-usret) III. This queen, they think, was a Hittite princess, and the Hittites were practically the same thing as the Hyksos. We have seen, however, that there is very little foundation for this view, and it is more than probable that this peculiar physiognomy is of a type purely Egyptian in character.

On The Platform Of The XIth Dynasty Temple, Der El-Bahari,

1904.

On the platform, around the central pyramid, were buried in small chamber-tombs a number of priestesses of the goddess Hathor, the mistress of the desert and special deity of Dêr el-Bahari. They were all members of the king's harîm, and they bore the title of "King's Favourite." As told in a previous chapter, all were buried at one time, before the final completion of the temple, and it is by no means impossible that they were strangled at the king's death and buried round him in order that their ghosts might accompany him in the next world, just as the slaves were buried around the graves (or secondary graves) of the 1st Dynasty kings at Aby-dos. They themselves, as also already related, took with them to the next world little waxen figures which when called upon could by magic be turned into ghostly slaves. These images were ushabtiu, "answerers," the predecessors of the little figures of wood, stone, and pottery which are found buried with the dead in later times. The priestesses themselves were, so to speak, human ushabtiu, for royal use only, and accompanied the kings to their final resting-place.

With the priestesses was buried the usual funerary furniture characteristic of the period. This consisted of little models of granaries with the peasants bringing in the corn, models of bakers and brewers at work, boats with their crews, etc., just as we find them in the XIth and XIIth Dynasty tombs at el-Bersha and Beni Hasan. These models, too, were supposed to be transformed by magic into actual workmen who would work for the deceased, heap up grain for her, brew beer for her, ferry her over the ghostly Nile into the tomb-world, or perform any other services required.

Some of the stone sarcophagi of the priestesses are very elaborately decorated with carved and painted reliefs depicting each deceased receiving offerings from priests, one of whom milks the holy cows of Hathor to give her milk. The sarcophagi were let down into the tomb in pieces and there joined together, and they have been removed in the same way. The finest is a unique example of XIth Dynasty art, and it is now preserved in the Museum of Cairo.

In memory of the priestesses there were erected on the platform behind the pyramid a number of small shrines, which were decorated with the most delicately coloured carvings in high relief, representing chiefly the same subjects as those on the sarcophagi. The peculiar style of these reliefs was previously unknown. In connection with them a most interesting possibility presents itself.

We know the name of the chief artist of Mentuhetep's reign. He was called Mertisen, and he thus describes himself on his tombstone from Abydos, now in the Louvre: "I was an artist skilled in my art. I knew my art, how to represent the forms of going forth and returning, so that each limb may be in its proper place. I knew how the figure of a man should walk and the carriage of a woman, the poising of the arm to bring the hippopotamus low, the going of the runner. I knew how to make amulets, which enable us to go without fire burning us and without the flood washing us away. No man could do this but I, and the eldest son of my body. Him has the god decreed to excel in art, and I have seen the perfections of the work of his hands in every kind of rare stone, in gold and silver, in ivory and ebony." Now since Mertisen and his son were the chief artists of their day, it is more than probable that they were employed to decorate their king's funerary chapel. So that in all probability the XIth Dynasty reliefs from Dêr el-Bahari are the work of Mertisen and his son, and in them we see the actual "forms of going forth and returning, the poising of the arm to bring the hippopotamus low, the going of the runner," to which he refers on his tombstone. This adds a note of personal interest to the reliefs, an interest which is often sadly wanting in Egypt, where we rarely know the names of the great artists whose works we admire so much. We have recovered the names of the sculptor and painter of Seti I's temple at Abydos and that of the sculptor of some of the tombs at Tell el-Amarna, but otherwise very few names of the artists are directly associated with the temples and tombs which they decorated, and of the architects we know little more. The great temple of Dêr el-Bahari was, however, we know, designed by Senmut, the chief architect to Queen Hatshepsu.

It is noticeable that Mertisen's art, if it is Mertisen's, is of a peculiar character. It is not quite so fully developed as that of the succeeding XIIth Dynasty. The drawing of the figures is often peculiar, strange lanky forms taking the place of the perfect proportions of the IVth-VIth and the XIIth Dynasty styles. Great elaboration is bestowed upon decoration, which is again of a type rather archaic in character when compared with that of the XIIth Dynasty. We are often reminded of the rude sculptures which used to be regarded as typical of the art of the XIth Dynasty, while at the same time we find work which could not be surpassed by the best XIIth Dynasty masters. In fact, the art of Neb-hapet-Râ's reign was the art of a transitional period. Under the decadent Memphites of the VIIth and VIIIth Dynasties, Egyptian art rapidly fell from the high estate which it had attained under the Vth Dynasty, and, though good work was done under the Hierakonpolites, the chief characteristic of Egyptian art at the time of the Xth and early XIth Dynasties is its curious roughness and almost barbaric appearance. When, however, the kings of the XIth Dynasty reunited the whole land under one sceptre, and the long reign of Neb-hapet-Râ Mentuhetep enabled the reconsolidation of the realm to be carried out by one hand, art began to revive, and, just as to Neb-hapet-Râ must be attributed the renascence of the Egyptian state under the hegemony of Thebes, so must the revival of art in his reign be attributed to his great artists, Mertisen and his son. They carried out in the realm of art what their king had carried out in the political realm, and to them must be attributed the origin of the art of the Middle Kingdom which under the XIIth Dynasty attained so high a pitch of excellence. The sculptures of the king's temple at Dêr el-Bahari, then, are monuments of the renascence of Egyptian art, after the state of decadence into which it had fallen during the long civil wars between South and North; it is a reviving art, struggling out of barbarism to regain perfection, and therefore has much about it that seems archaic, stiff, and curious when compared with later work. To the XVIIIth Dynasty Egyptian it would no doubt have seemed hopelessly old-fashioned and even semi-barbarous, and he had no qualms about sweeping it aside whenever it appeared in the way of the work of his own time; but to us this very strangeness gives additional charm and interest, and we can only be thankful that Mertisen's work has lasted (in fragments only, it is true) to our own day, to tell us the story of a little known chapter in the history of ancient Egyptian art.

From this description it will have been seen that the temple is an important monument of the Egyptian art and architecture of the Middle Kingdom. It is the only temple of that period of which considerable traces have been found, and on that account the study of it will be of the greatest interest. It is the best preserved of the older temples of Egypt, and at Thebes it is by far the most ancient building recovered. Historically it has given us a new king of the XIth Dynasty, Sekhâhe-tep-Râ Mentuhetep, and the name of the queen of Neb-hapet-Râ Mentuhetep, Aasheit, who seems to have been an Ethiopian, to judge from her portrait, which has been discovered. It is interesting to note that one of the priestesses was a negress.

The name Neb-hapet-Râ may be unfamiliar to those readers who are acquainted with the lists of the Egyptian kings. It is a correction of the former reading, "Neb-kheru-Râ," which is now known from these excavations to be erroneous. Neb-hapet-Râ (or, as he used to be called, Neb-kheru-Râ) is Mentuhetep III of Prof. Petrie's arrangement. Before him there seem to have come the kings Mentuhetep Neb-hetep (who is also commemorated in this temple) and Neb-taui-Râ; after him, Sekhâhetep-Râ Mentuhetep IV and Seânkhkarâ Mentuhetep V, who were followed by an Antef, bearing the banner or hawk-name Uah-ânkh. This king was followed by Amenemhat I, the first king of the XIIth Dynasty. Antef Uah-ânkh may be numbered Antef I, as the prince Antefa, who founded the XIth Dynasty, did not assume the title of king.

Other kings of the name of Antef also ruled over Egypt, and they used to be regarded as belonging to the XIth Dynasty; but Prof. Steindorff has now proved that they really reigned after the XIIIth Dynasty, and immediately before the Sekenenrâs, who were the fighters of the Hyksos and predecessors of the XVIIIth Dynasty. The second names of Antef III (Seshes-Râ-up-maat) and Antef IV (Seshes-Râ-her-her-maat) are exactly similar to those of the XIIIth Dynasty kings and quite unlike those of the Mentuheteps; also at Koptos a decree of Antef II (Nub-kheper-Râ) has been found inscribed on a doorway of Usertsen (Senusret) I; so that he cannot have preceded him. Prof. Petrie does not yet accept these conclusions, and classes all the Antefs together with the Mentuheteps in the XIth Dynasty. He considers that he has evidence from Herakleopolis that Antef Xub-kheper-Râ (whom he numbers Antef V) preceded the XIIth Dynasty, and he supposes that the decree of Nub-kheper-Râ at Koptos is a later copy of the original and was inscribed during the XIIth Dynasty. But this is a difficult saying. The probabilities are that Prof. Steindorff is right. Antef Uah-ânkh must, however, have preceded the XIIth Dynasty, since an official of that period refers to his father's father as having lived in Uah-ânkh 's time.

The necropolis of Dêr el-Bahari was no doubt used all through the period of the XIth and XIIth Dynasties, and many tombs of that period have been found there. A large number of these were obliterated by the building of the great temple of Queen Hatshepsu, in the northern part of the cliff-bay. We know of one queen's tomb of that period which runs right underneath this temple from the north, and there is another that is entered at the south side which also runs down underneath it. Several tombs were likewise found in the court between it and the XIth Dynasty temple. We know that the XVIIIth Dynasty temple was largely built over this court, and we can see now the XIth Dynasty mask-wall on the west of the court running northwards underneath the mass of the XVIIIth Dynasty temple. In all probability, then, when the temple of Hatshepsu was built, the larger portion of the Middle Kingdom necropolis (of chamber-tombs reached by pits), which had filled up the bay to the north of the Mentuhetep temple, was covered up and obliterated, just as the older VIth Dynasty gallery tombs of Shêkh Abd el-Kûrna had been appropriated and altered at the same period.

The kings of the XIIth and XIIIth Dynasties were not buried at Thebes, as we have seen, but in the North, at Dashûr, Lisht, and near the Fayymn, with which their royal city at Itht-taui had brought them into contact. But at the end of the XIIIth Dynasty the great invasion of the Hyksos probably occurred, and all Northern Egypt fell under the Arab sway. The native kings were driven south from the Fayymn to Abydos, Koptos, and Thebes, and at Thebes they were buried, in a new necropolis to the north of Dêr el-Bahari (probably then full), on the flank of a long spur of hill which is now called Dra' Abu-'l-Negga, "Abu-'l-Negga's Arm." Here the Theban kings of the period between the XIIIth and XVIIth Dynasties, Upuantemsaf, Antef Nub-kheper-Râ, and his descendants, Antefs III and IV, were buried. In their time the pressure of foreign invasion seems to have been felt, for, to judge from their coffins, which show progressive degeneration of style and workmanship, poverty now afflicted Upper Egypt and art had fallen sadly from the high standard which it had reached in the days of the XIth and XIIth Dynasties. Probably the later Antefs and Sebekemsafs were vassals of the Hyksos. Their descendants of the XVIIth Dynasty were buried in the same necropolis of Dra' Abu-'l-Negga, and so were the first two kings of the XVIIIth Dynasty, Aahmes and Amenhetep I. The tombs of the last two have not yet been found, but we know from the Abbott Papyrus that Amenhetep's was here, for, like that of Menttihetep III, it was found intact by the inspectors. It was a gallery-tomb of very great length, and will be a most interesting find when it is discovered, as it no doubt eventually will be. Aahmes had a tomb at Abydos, which was discovered by Mr. Currelly, working for the Egypt Exploration Fund. This, however, like the Abydene tomb of Usert-sen (Senusret) III, was in all likelihood a sham or secondary tomb, the king having most probably been buried at Thebes, in the Dra' Abu-'l-Negga. The Abydos tomb is of interesting construction. The entrance is by a simple pit, from which a gallery runs round in a curving direction to a great hall supported by eighteen square pillars, beyond which is a further gallery which was never finished. Nothing was found in the tomb. On the slope of the mountain, due west of and in a line with the tomb, Mr. Currelly found a terrace-temple analogous to those of Dêr el-Bahari, approached not by means of a ramp but by stairways at the side. It was evidently the funerary temple of the tomb.

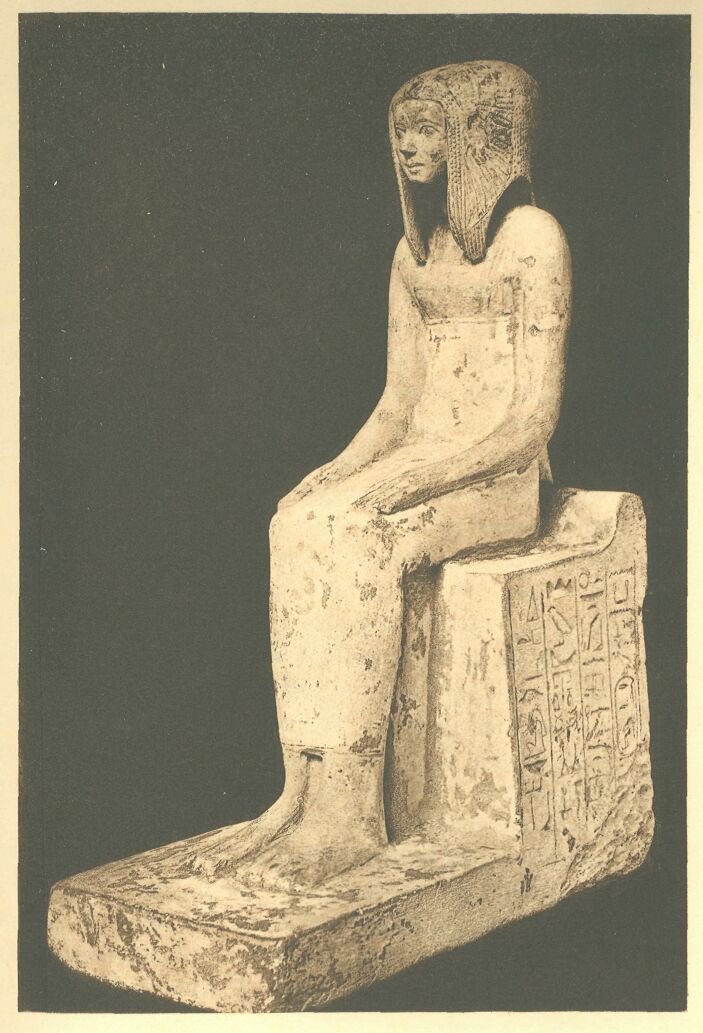

Grandmother of Aahmes, the conqueror of the Hyksos and

founder of the XVIIIth Dynasty. About 1700 B. C. British

Museum. From the photograph by Messrs. Mansell & Co.

The secondary tomb of Usertsen (Senusret) III at Abydos, which has already been mentioned, was discovered in the preceding year by Mr. A. E. P. Weigall, and excavated by Mr. Currelly in 1903. It lies north of the Aahmes temple, between it and the main cemetery of Abydos. It is a great bâb or gallery-tomb, like those of the later kings at Thebes, with the usual apparatus of granite plugs, barriers, pits, etc., to defy plunderers. The tomb had been plundered, nevertheless, though it is probable that the robbers were vastly disappointed with what they found in it. Mr. Currelly ascribes the absence of all remains to the plunderers, but the fact is that there probably never was anything in it but an empty sarcophagus. Near the tomb Mr. Weigall discovered some dummy mastabas, a find of great interest. Just as the king had a secondary tomb, so secondary mastabas, mere dummies of rubble like the XIth Dynasty pyramid at Dêr el-Bahari, were erected beside it to look like the tombs of his courtiers. Some curious sinuous brick walls which appear to act as dividing lines form a remarkable feature of this sham cemetery. In a line with the tomb, on the edge of the cultivation, is the funerary temple belonging to it, which was found by Mr. Randall-Maclver in 1900. Nothing remains but the bases of the fluted limestone columns and some brick walls. A headless statue of Usertsen was found.

We have an interesting example of the custom of building a secondary tomb for royalties in these two nécropoles of Dra' Abu-'l-Negga and Abydos. Queen Teta-shera, the grandmother of Aahmes, a beautiful statuette of whom may be seen in the British Museum, had a small pyramid at Abydos, eastward of and in a line with the temple and secondary tomb of Aahmes. In 1901 Mr. Mace attempted to find the chamber, but could not. In the next year Mr. Currelly found between it and the Aahmes tomb a small chapel, containing a splendid stele, on which Aahmes commemorates his grandmother, who, he says, was buried at Thebes and had a mer-âhât at Abydos, and he records his determination to build her also a pyramid at Abydos, out of his love and veneration for her memory. It thus appeared that the pyramid to the east was simply a dummy, like Usertsen's mastabas, or the Mentuhetep pyramid at Dêr el-Bahari. Teta-shera was actually buried at Dra' Abu-'l-Negga. Her secondary pyramid, like that of Aahmes himself, was in the "holy ground" at Abydos, though it was not an imitation bâb, but a dummy pyramid of rubble. This well illustrates the whole custom of the royal primary and secondary tombs, which, as we have seen, had obtained in the case of royal personages from the time of the 1st Dynasty, when Aha had two tombs, one at Nakâda and the other at Abydos. It is probable that all the 1st Dynasty tombs at Abydos are secondary, the kings being really buried elsewhere. After their time we know for certain that Tjeser and Snefru had duplicate tombs, possibly also Unas, and certainly Usertsen (Senusret) III, Amenemhat III, and Aahmes; while Mentuhetep III and Queen Teta-shera had dummy pyramids as well as their tombs. Ramses III also had two tombs, both at Thebes. The reasons for this custom were two: first, the desire to elude plunderers, and second, the wish to give the ghost a pied-à-terre on the sacred soil of Abydos or Sakkâra.

As the inscription of Aahmes which records the building of the dummy pyramid of Teta-shera is of considerable interest, it may here be translated. The text reads: "It came to pass that when his Majesty the king, even the king of South and North, Neb-pehti-Râ, Son of the Sun, Aahmes, Giver of Life, was taking his pleasure in the tjadu-hall, the hereditary princess greatly favoured and greatly prized, the king's daughter, the king's sister, the god's wife and great wife of the king, Nefret-ari-Aahmes, the living, was in the presence of his Majesty. And the one spake unto the other, seeking to do honour to These There,* which consisteth in the pouring of water, the offering upon the altar, the painting of the stele at the beginning of each season, at the Festival of the New Moon, at the feast of the month, the feast of the going-forth of the Sem-priest, the Ceremonies of the Night, the Feasts of the Fifth Day of the Month and of the Sixth, the Hak-festival, the Uag-festival, the feast of Thoth, the beginning of every season of heaven and earth. And his sister spake, answering him: 'Why hath one remembered these matters, and wherefore hath this word been said? Prithee, what hath come into thy heart?' The king spake, saying: 'As for me, I have remembered the mother of my mother, the mother of my father, the king's great wife and king's mother Teta-shera, deceased, whose tomb-chamber and mer-ahât are at this moment upon the soil of Thebes and Abydos. I have spoken thus unto thee because my Majesty desireth to cause a pyramid and chapel to be made for her in the Sacred Land, as a gift of a monument from my Majesty, and that its lake should be dug, its trees planted, and its offerings prescribed; that it should be provided with slaves, furnished with lands, and endowed with cattle, with hen-ka priests and kher-heb priests performing their duties, each man knowing what he hath to do.' Behold! when his Majesty had thus spoken, these things were immediately carried out. His Majesty did these things on account of the greatness of the love which he bore her, which was greater than anything. Never had ancestral kings done the like for their mothers. Behold! his Majesty extended his arm and bent his hand, and made for her the king's offering to Geb, to the Ennead of Gods, to the lesser Ennead of Gods... [to Anubis] in the God's Shrine, thousands of offerings of bread, beer, oxen, geese, cattle... to [the Queen Teta-shera]." This is one of the most interesting inscriptions discovered in Egypt in recent years, for the picturesqueness of its diction is unusual.

* A polite periphrasis for the dead.

As has already been said, the king Amenhetep I was also buried in the Dra' Abu-'l-Negga, but the tomb has not yet been found. Amenhetep I and his mother, Queen Nefret-ari-Aahmes, who is mentioned in the inscription translated above, were both venerated as tutelary demons of the Western Necropolis of Thebes after their deaths, as also was Mentuhetep III. At Dêr el-Bahari both kings seem to have been worshipped with Hathor, the Mistress of the Waste. The worship of Amen-Râ in the XVIIIth Dynasty temple of Dêr el-Bahari was a novelty introduced by the priests of Amen at that time. But the worship of Hathor went on side by side with that of Amen in a chapel with a rock-cut shrine at the side of the Great Temple. Very possibly this was the original cave-shrine of Hathor, long before Mentuhetep's time, and was incorporated with the Great Temple and beautified with the addition of a pillared hall before it, built over part of the XIth Dynasty north court and wall, by Hatshepsu's architects.

The Great Temple, the excavation of which for the Egypt Exploration Fund was successfully brought to an end by Prof. Naville in 1898, was erected by Queen Hatshepsu in honour of Amen-Râ, her father Thothmes I, and her brother-husband Thothmes II, and received a few additions from Thothmes III, her successor. He, however, did not complete it, and it fell into disrepair, besides suffering from the iconoclastic zeal of the heretic Akhunaten, who hammered out some of the beautifully painted scenes upon its walls. These were badly restored by Ramses II, whose painting is easily distinguished from the original work by the dulness and badness of its colour.

The peculiar plan and other remarkable characteristics of this temple are well known. Its great terraces, with the ramps leading up to them, flanked by colonnades, which, as we have seen, were imitated from the design of the old XIth Dynasty temple at its side, are familiar from a hundred illustrations, and the marvellously preserved colouring of its delicate reliefs is known to every winter visitor to Egypt, and can be realized by those who have never been there through the medium of Mr. Howard Carter's wonderful coloured reproductions, published in Prof. Naville's edition of the temple by the Egypt Exploration Fund. The Great Temple stands to-day clear of all the débris which used to cover it, a lasting monument to the work of the greatest of the societies which busy themselves with the unearthing of the relics of the ancient world.

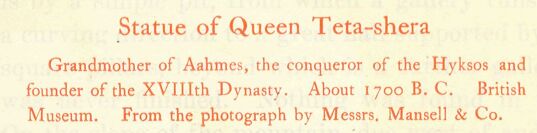

The two temples of Dêr el-Bahari will soon stand side by side, as they originally stood, and will always be associated with the name of the society which rescued them from oblivion, and gave us the treasures of the royal tombs at Abydos. The names of the two men whom the Egypt Exploration Fund commissioned to excavate Dêr el-Bahari and Abydos, and for whose work it exclusively supplied the funds, Profs. Naville and Petrie, will live chiefly in connection with their work at Dêr el-Bahari and Abydos.

The Egyptians called the two temples Tjeserti, "the two holy places," the new building receiving the name of Tjeser-tjesru, "Holy of Holies," and the whole tract of Dêr el-Bahari the appellation Tjesret, "the Holy." The extraordinary beauty of the situation in which they are placed, with its huge cliffs and rugged hillsides, may be appreciated from the photograph which is taken from a steep path half-way up the cliff above the Great Temple. In it we see the Great Temple in the foreground with the modern roofs of two of its colonnades, devised in order to protect the sculptures beneath them, the great trilithon gate leading to the upper court, and the entrance to the cave-shrine of Amen-Râ, with the niches of the kings on either side, immediately at the foot of the cliff. In the middle distance is the duller form of the XIth Dynasty temple, with its rectangular platform, the ramp leading up to it, and the pyramid in the centre of it, surrounded by pillars, half-emerging from the great heaps of sand and débris all around. The background of cliffs and hills, as seen in the photograph, will serve to give some idea of the beauty of the surroundings,—an arid beauty, it is true, for all is desert. There is not a blade of vegetation near; all is salmon-red in colour beneath a sky of ineffable blue, and against the red cliffs the white temple stands out in vivid contrast.

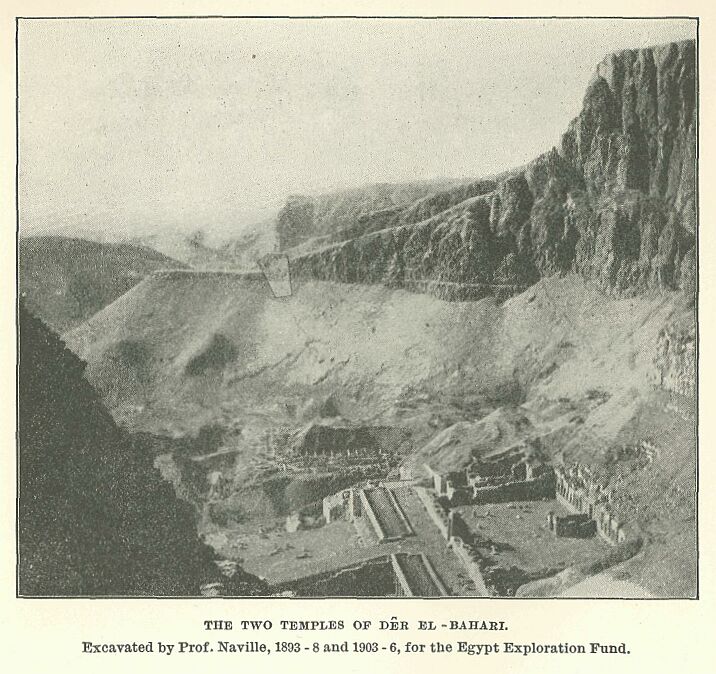

The second illustration gives a nearer view of the great trilithon gate in the upper court, at the head of the ramp. The long hill of Dra' Abu-'l-Negga is seen bending away northward behind the gate.

Of The Xviiith Dynasty Temple At Dêk El-Bahari. About 1500

B.C.

This is the famous gate on which the jealous Thothmes III chiselled out Hatshepsu's name in the royal cartouches and inserted his own in its place; but he forgot to alter the gender of the pronouns in the accompanying inscription, which therefore reads "King Thothmes III, she made this monument to her father Amen."

Among Prof. Naville's discoveries here one of the most important is that of the altar in a small court to the north, which, as the inscription says, was made in honour of the god Râ-Harmachis "of beautiful white stone of Anu." It is of the finest white limestone known. Here also were found the carved ebony doors of a shrine, now in the Cairo Museum. One of the most beautiful parts of the temple is the Shrine of Anubis, with its splendidly preserved paintings and perfect columns and roof of white limestone. The effect of the pure white stone and simplicity of architecture is almost Hellenic.

The Shrine of Hathor has been known since the time of Mariette, but in connection with it some interesting discoveries have been made during the excavation of the XIth Dynasty temple. In the court between the two temples were found a large number of small votive offerings, consisting of scarabs, beads, little figures of cows and women, etc., of blue glazed faïence and rough pottery, bronze and wood, and blue glazed ware ears, eyes, and plaques with figures of the sacred cow, and other small objects of the same nature. These are evidently the ex-votos of the XVIIIth Dynasty fellahîn to the goddess Hathor in the rock-shrine above the court. When the shrine was full or the little ex-votos broken, the sacristans threw them over the wall into the court below, which thus became a kind of dust-heap. Over this heap the sand and débris gradually collected, and thus they were preserved. The objects found are of considerable interest to anthropological science.

The Great Temple was built, as we have said, in honour of Thothmes I and II, and the deities Amen-Râ and Hathor. More especially it was the funerary chapel of Thothmes I. His tomb was excavated, not in the Dra' Abu-l-Negga, which was doubtless now too near the capital city and not in a sufficiently dignified position of aloofness from the common herd, but at the end of the long valley of the Wadiyên, behind the cliff-hill above Dêr el-Bahari. Hence the new temple was oriented in the direction of his tomb. Immediately behind the temple, on the other side of the hill, is the tomb which was discovered by Lepsius and cleared in 1904 for Mr. Theodore N. Davis by Mr. Howard Carter, then chief inspector of antiquities at Thebes. Its gallery is of very small dimensions, and it winds about in the hill in corkscrew fashion like the tomb of Aahmes at Aby-dos. Owing to its extraordinary length, the heat and foul air in the depths of the tomb were almost insupportable and caused great difficulty to the excavators. When the sarcophagus-chamber was at length reached, it was found to contain the empty sarcophagi of Thothmes I and of Hatshepsu. The bodies had been removed for safe-keeping in the time of the XXIst Dynasty, that of Thothmes I having been found with those of Set! I and Ramses II in the famous pit at Dêr el-Bahari, which was discovered by M. Maspero in 1881. Thothmes I seems to have had another and more elaborate tomb (No. 38) in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings, which was discovered by M. Loret in 1898. Its frescoes had been destroyed by the infiltration of water.

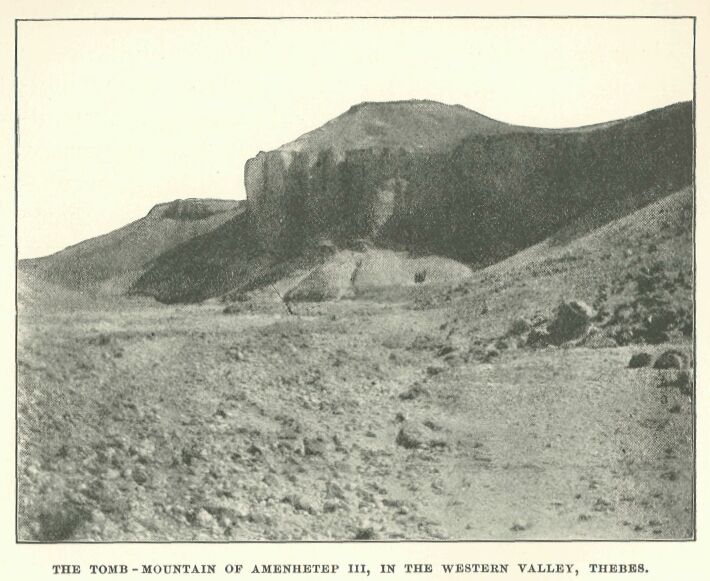

The fashion of royal burial in the great valley behind Dêr el-Bahari was followed during the XVIIIth, XIXth, and XXth Dynasties. Here in the eastern branch of the Wadiyên, now called the Bibân el-Mulûk, "the Tombs of the Kings," the greater number of the mightiest Theban Pharaohs were buried. In the western valley rested two of the kings of the XVIIIth Dynasty, who desired even more remote burial-places, Amenhetep III and Ai. The former chose for his last home a most kingly site. Ancient kings had raised great pyramids of artificial stone over their graves. Amenhetep, perhaps the greatest and most powerful Pharaoh of them all, chose to have a natural pyramid for his grave, a mountain for his tumulus. The illustration shows us the tomb of this monarch, opening out of the side of one of the most imposing hills in the Western Valley. No other king but Amenhetep rested beneath this hill, which thus marks his grave and his only.

It is in the Eastern Valley, the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings properly speaking, that the tombs of Thothmes I and Hatshepsu lie, and here the most recent discoveries have been made. It is a desolate spot. As we come over the hill from Dêr el-Bahari we see below us in the glaring sunshine a rocky canon, with sides sometimes sheer cliff, sometimes sloped by great falls of rock in past ages. At the bottom of these slopes the square openings of the many royal tombs can be descried. [See illustration.] Far below we see the forms of tourists and the tomb-guards accompanying them, moving in and out of the openings like ants going in and out of an ants' nest. Nothing is heard but the occasional cry of a kite and the ceaseless rhythmical throbbing of the exhaust-pipe of the electric light engine in the unfinished tomb of Ramses XI. Above and around are the red desert hills. The Egyptians called it "The Place of Eternity."

In this valley some remarkable discoveries have been made during the last few years. In 1898 M. Grébaut discovered the tomb of Amenhetep II, in which was found the mummy of the king, intact, lying in its sarcophagus in the depths of the tomb. The royal body now lies there for all to see. The tomb is lighted with electricity, as are all the principal tombs of the kings. At the head of the sarcophagus is a single lamp, and, when the party of visitors is collected in silence around the place of death, all the lights are turned out, and then the single light is switched on, showing the royal head illuminated against the surrounding blackness. The effect is indescribably weird and impressive. The body has only twice been removed from the tomb since its burial, the second time when it was for a brief space taken up into the sunlight to be photographed by Mr.. Carter, in January, 1902. The temporary removal was carefully carried out, the body of his Majesty being borne up through the passages of the tomb on the shoulders of the Italian electric light workmen, preceded and followed by impassive Arab candle-bearers. The workmen were most reverent in their handling of the body of " il gran ré," as they called him.

In the tomb were found some very interesting objects, including a model boat (afterwards stolen), across which lay the body of a woman. This body now lies, with others found close by, in a side chamber of the tomb. One may be that of Hatshepsu. The walls of the tomb-chamber are painted to resemble papyrus, and on them are written chapters of the "Book of What Is in the Underworld," for the guidance of the royal ghost.

In 1902-3 Mr. Theodore Davis excavated the tomb of Thothmes IV. It yielded a rich harvest of antiquities belonging to the funeral state of the king, including a chariot with sides of embossed and gilded leather, decorated with representations of the king's warlike deeds, and much fine blue pottery, all of which are now in the Cairo Museum. The tomb-gallery returns upon itself, describing a curve. An interesting point with regard to it is that it had evidently been violated even in the short time between the reigns of its owner and Horem-heb, probably in the period of anarchy which prevailed at Thebes during the reign of the heretic Akhunaten; for in one of the chambers is a hieratic inscription recording the repair of the tomb in the eighth year of Horemheb by Maya, superintendent of works in the Tombs of the Kings. It reads as follows: "In the eighth year, the third month of summer, under the Majesty of King Tjeser-khepru-Râ Sotp-n-Râ, Son of the Sun, Horemheb Meriamen, his Majesty (Life, health, and wealth unto him!) commanded that orders should be sent unto the Fanbearer on the King's Left Hand, the King's Scribe and Overseer of the Treasury, the Overseer of the Works in the Place of Eternity, the Leader of the Festivals of Amen in Karnak, Maya, son of the judge Aui, born of the Lady Ueret, that he should renew the burial of King Men-khepru-Râ, deceased, in the August Habitation in Western Thebes." Men-khepru-Râ was the prenomen or throne-name of Thothmes IV. Tied round a pillar in the tomb is still a length of the actual rope used by the thieves for crossing the chasm, which, as in many of the tombs here, was left open in the gallery to bar the way to plunderers. The mummy of the king was found in the tomb of Amenhetep II, and is now at Cairo.

The discovery of the tomb of Thothmes I and Hat-shepsu has already been described. In 1905 Mr. Davis made his latest find, the tomb of Iuaa and Tuaa, the father and mother of Queen Tii, the famous consort of Amenhetep III and mother of Akhunaten the heretic. Readers of Prof. Maspero's history will remember that Iuaa and Tuaa are mentioned on one of the large memorial scarabs of Amenhetep III, which commemorates his marriage. The tomb has yielded an almost incredible treasure of funerary furniture, besides the actual mummies of Tii's parents, including a chariot overlaid with gold. Gold overlay of great thickness is found on everything, boxes, chairs, etc. It was no wonder that Egypt seemed the land of gold to the Asiatics, and that even the King of Babylon begs this very Pharaoh Amenhetep to send him gold, in one of the letters found at Tell el-Amarna, "for gold is as water in thy land." It is probable that Egypt really attained the height of her material wealth and prosperity in the reign of Amenhetep III. Certainly her dominion reached its farthest limits in his time, and his influence was felt from the Tigris to the Sudan. He hunted lions for his pleasure in Northern Mesopotamia, and he built temples at Jebel Barkal beyond Dongola. We see the evidence of lavish wealth in the furniture of the tomb of Iuaa and Tuaa. Yet, fine as are many of these gold-overlaid and overladen objects of the XVIIIth Dynasty, they have neither the good taste nor the charm of the beautiful jewels from the XIIth Dynasty tombs at Dashûr. It is mere vulgar wealth. There is too much gold thrown about. "For gold is as water in thy land." In three hundred years' time Egypt was to know what poverty meant, when the poor priest-kings of the XXIst Dynasty could hardly keep body and soul together and make a comparatively decent show as Pharaohs of Egypt. Then no doubt the latter-day Thebans sighed for the good old times of the XVIIIth Dynasty, when their city ruled a considerable part of Africa and Western Asia and garnered their riches into her coffers. But the days of the XIIth Dynasty had really been better still. Then there was not so much wealth, but what there was (and there was as much gold then, too) was used sparingly, tastefully, and simply. The XIIth Dynasty, not the XVIIIth, was the real Golden Age of Egypt.

From the funeral panoply of a tomb like that of Iuaa and Tuaa we can obtain some idea of the pomp and state of Amenhetep III. But the remains of his Theban palace, which have been discovered and excavated by Mr. C. Tytus and Mr. P. E. Newberry, do not bear out this idea of magnificence. It is quite possible that the palace was merely a pleasure house, erected very hastily and destined to fall to pieces when its owner tired of it or died, like the many palaces of the late Khedive Ismail. It stood on the border of an artificial lake, whereon the Pharaoh and his consort Tii sailed to take their pleasure in golden barks. This is now the cultivated rectangular space of land known as the Birket Habû, which is still surrounded by the remains of the embankment built to retain its waters, and becomes a lake during the inundation. On the western shore of this lake Amenhetep erected the "stately pleasure dome," the remains of which still cover the sandy tract known as el-Malkata, "the Salt-pans," south of the great temple of Medînet Habû. These remains consist merely of the foundations and lowest wall-courses of a complicated and rambling building of many chambers, constructed of common unburnt brick and plastered with white stucco on walls and floors, on which were painted beautiful frescoes of fighting bulls, birds of the air, water-fowl, fish-ponds, etc., in much the same style as the frescoes of Tell el-Amarna executed in the next reign. There were small pillared halls, the columns of which were of wood, mounted on bases of white limestone. The majority still remain in position. In several chambers there are small daïses, and in one the remains of a throne, built of brick and mud covered with plaster and stucco, upon which the Pharaoh Amenhetep sat. This is the palace of him whom the Greeks called Memnon, who ruled Egypt when Israel was in bondage and when the dynasty of Minos reigned in Crete. Here by the side of his pleasure-lake the most powerful of Egyptian Pharaohs whiled away his time during the summer heats. Evidently the building was intended to be of the lightest construction, and never meant to last; but to our ideas it seems odd that an Egyptian Pharaoh should live in a mud palace. Such a building is, however, quite suited to the climate of Egypt, as are the modern crude brick dwellings of the fellahîn. In the ruins of the palace were found several small objects of interest, and close by was an ancient glass manufactory of Amenhetep III's time, where much of the characteristic beautifully coloured and variegated opaque glass of the period was made.

The tombs of the magnates of Amenhetep III's reign and of the reigns of his immediate predecessors were excavated, as has been said, on the eastern slope of the hill of Shêkh 'Abd el-Kûrna, where was the earliest Theban necropolis. No doubt many of the early tombs of the time of the VIth Dynasty were appropriated and remodelled by the XVIIIth Dynasty magnates. We have an instance of time's revenge in this matter, in the case of the tomb of Imadua, a great priestly official of the time of the XXth Dynasty. This tomb previously belonged to an XVIIIth Dynasty worthy, but Imadua appropriated it three hundred years later and covered up all its frescoes with the much begilt decoration fashionable in his period. Perhaps the XVIIIth Dynasty owner had stolen it from an original owner of the time of the VIth Dynasty. The tomb has lately been cleared out by Mr. Newberry.

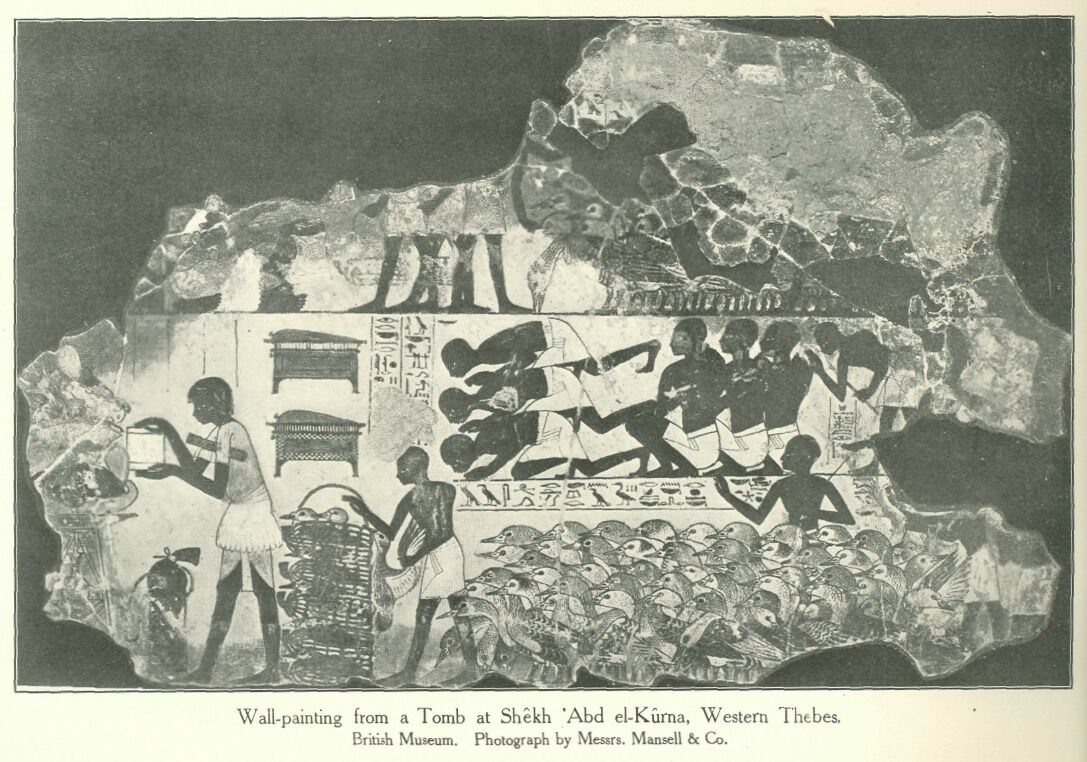

Much work of the same kind has been done here of late years by Messrs. Newberry and R. L. Mond, in succession. To both we are indebted for the excavation of many known tombs, as well as for the discovery of many others previously unknown. Among the former was that of Sebekhetep, cleared by Mr. Newberry. Se-bekhetep was an official of the time of Thothmes III. From his tomb, and from others in the same hill, came many years ago the fine frescoes shown in the illustration, which are among the most valued treasures of the Egyptian department of the British Museum. They are typical specimens of the wall-decoration of an XVIIIth Dynasty tomb. On one may be seen a bald-headed peasant, with staff in hand, pulling an ear of corn from the standing crop in order to see if it is ripe. He is the "Chief Reaper," and above him is a prayer that the "great god in heaven" may increase the crop. To the right of him is a charioteer standing beside a car and reining back a pair of horses, one black, the other bay. Below is another charioteer with two white horses. He sits on the floor of the car with his back to them, eating or resting, while they nibble the branches of a tree close by. Another scene is that of a scribe keeping tally of offerings brought to the tomb, while fellahm are bringing flocks of geese and other fowl, some in crates. The inscription above is apparently addressed by the goose-herd to the man with the crates. It reads: "Hasten thy feet because of the geese! Hearken! thou knowest not the next minute what has been said to thee!" Above, a reïs with a stick bids other peasants squat on the ground before addressing the scribe, and he is saying to them: "Sit ye down to talk." The third scene is in another style; on it may be seen Semites bringing offerings of vases of gold, silver, and copper to the royal presence, bowing themselves to the ground and kissing the dust before the throne. The fidelity and accuracy with which the racial type of the tribute-bearers is given is most extraordinary; every face seems a portrait, and each one might be seen any day now in the Jewish quarters of Whitechapel.

The first two paintings are representative of a very common style of fresco-pictures in these tombs. The care with which the animals are depicted is remarkable. Possibly one of the finest Egyptian representations of an animal is the fresco of a goat in the tomb of Gen-Amen, discovered by Mr. Mond. There is even an attempt here at chiaroscuro, which is unknown to Egyptian art generally, except at Tell el-Amarna. Evidently the Egyptian painters reached the apogee of their art towards the end of the XVIIIth Dynasty. The third, the representation of tribute-bearers, is of a type also well known at this period. In all the chief tombs we have processions of Egyptians, Westerners, Northerners, Easterners, and Southerners, bringing tribute to the Pharaoh. The North is represented by the Semites, the East by the Punites (when they occur), the South by negroes, the West by the Keftiu or people of Crete and Cyprus. The representations of the last-named people have become of the very highest interest during the last few years, on account of the discoveries in Crete, which have revealed to us the state and civilization of these very Keftiu. Messrs. Evans and Halbherr have discovered at Knossos and Phaistos the cities and palace-temples of the king who sent forth their ambassadors to far-away Egypt with gifts for the mighty Pharaoh; these ambassadors were painted in the tombs of their hosts as representative of the quarter of the world from which they came.

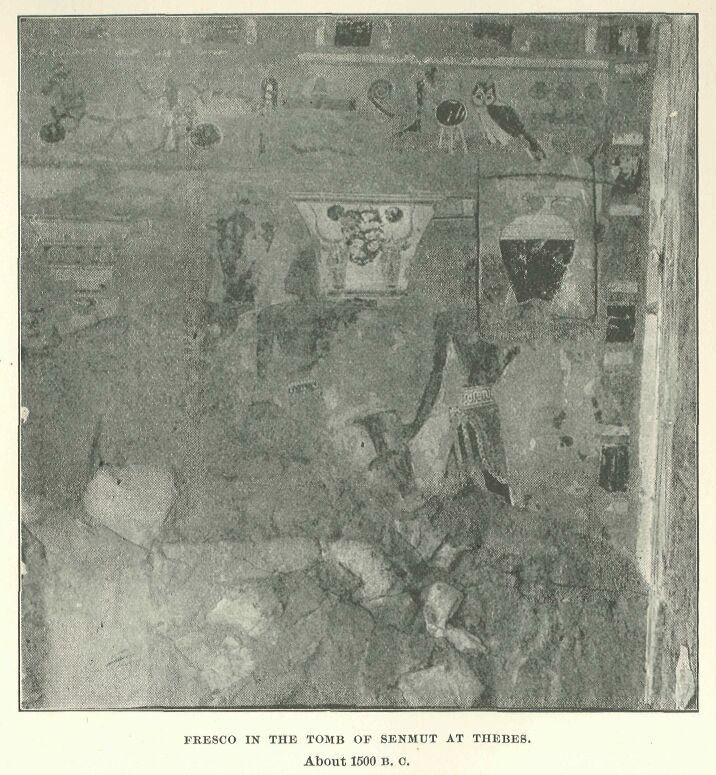

The two chief Egyptian representations of these people, who since they lived in Greece may be called Greeks, though their more proper title would be "Pe-lasgians," are to be found in the tombs of Rekhmarâ and Senmut, the former a vizier under Thothmes III, the latter the architect of Hatshepsu's temple at Dêr el-Bahari. Senmut's tomb is a new rediscovery. It was known, as Rekhmarâ's was, in the early days of Egyptological science, and Prisse d'Avennes copied its paintings. It was afterwards lost sight of until rediscovered by Mr. Newberry and Prof. Steindorff.

The tomb of Rekhmarâ (No. 35) is well known to every visitor to Thebes, but it is difficult to get at that of Senmut (No. 110); it lies at the top of the hill round to the left and overlooking Dêr el-Bahari, an appropriate place for it, by the way. In some ways Senmut's representations are more interesting than Rekhmarâ's. They are more easily seen, since they are now in the open air, the fore hall of the tomb having been ruined; and they are better preserved, since they have not been subjected to a century of inspection with naked candles and pawing with greasy hands, as have Rekhmarâ's frescoes. Further, there is no possibility of mistaking what they represent. From right to left, walking in procession, we see the Minoan gift-bearers from Crete, carrying in their hands and on their shoulders great cups of gold and silver, in shape like the famous gold cups found at Vaphio in Lakonia, but much larger, also a ewer of gold and silver exactly like one of bronze discovered by Mr. Evans two years ago at Knossos, and a huge copper jug with four ring-handles round the sides. All these vases are specifically and definitely Mycenaean, or rather, following the new terminology, Minoan. They are of Greek manufacture and are carried on the shoulders of Pelasgian Greeks. The bearers wear the usual Mycenaean costume, high boots and a gaily ornamented kilt, and little else, just as we see it depicted in the fresco of the Cupbearer at Knossos and in other Greek representations. The coiffure, possibly the most characteristic thing about the Mycenaean Greeks, is faithfully represented by the Egyptians both here and in Rekhmarâ's tomb. The Mycenaean men allowed their hair to grow to its full natural length, like women, and wore it partly hanging down the back, partly tied up in a knot or plait (the kepas of the dandy Paris in the Iliad) on the crown of the head. This was the universal fashion, and the Keftiu are consistently depicted by the XVIIIth Dynasty Egyptians as following it. The faces in the Senmut fresco are not so well portrayed as those in the Rekhmarâ fresco. There it is evident that the first three ambassadors are faithfully depicted, as the portraits are marked. The procession advances from left to right. The first man, "the Great Chief of the Kefti and the Isles of the Green Sea," is young, and has a remarkably small mouth with an amiable expression. His complexion is fair rather than dark, but his hair is dark brown. His lieutenant, the next in order, is of a different type,—elderly, with a most forbidding visage, Roman nose, and nutcracker jaws. Most of the others are very much alike,—young, dark in complexion, and with long black hair hanging below their waists and twisted up into fantastic knots and curls on the tops of their heads. One, carrying on his shoulder a great silver vase with curving handles and in one hand a dagger of early European Bronze Age type, is looking back to hear some remark of his next companion. Any one of these gift-bearers might have sat for the portrait of the Knossian Cupbearer, the fresco discovered by Mr. Evans in the palace-temple of Minos; he has the same ruddy brown complexion, the same long black hair dressed in the same fashion, the same parti-coloured kilt, and he bears his vase in much the same way. We have only to allow for the difference of Egyptian and Mycenaean ways of drawing. There is no doubt whatever that these Keftiu of the Egyptians were Cretans of the Minoan Age. They used to be considered Phoenicians, but this view was long ago exploded. They are not Semites, and that is quite enough. Neither are they Asiatics of any kind. They are purely and simply Mycenaean, or rather Minoan, Greeks of the pre-Hellenic period—Pelasgi, that is to say.

Probably no discovery of more far-reaching importance to our knowledge of the history of the world generally and of our own culture especially has ever been made than the finding of Mycenæ by Schliemann, and the further finds that have resulted therefrom, culminating in the discoveries of Mr. Arthur Evans at Knossos. Naturally, these discoveries are of extraordinary interest to us, for they have revealed the beginnings and first bloom of the European civilization of to-day. For our culture-ancestors are neither the Egyptians, nor the Assyrians, nor the Hebrews, but the Hellenes, and they, the Aryan-Greeks, derived most of their civilization from the pre-Hellenic people whom they found in the land before them, the Pelasgi or "Mycenæan" Greeks, "Minoans," as we now call them, the Keftiu of the Egyptians. These are the ancient Greeks of the Heroic Age, to which the legends of the Hellenes refer; in their day were fought the wars of Troy and of the Seven against Thebes, in their day the tragedy of the Atridse was played out to its end, in their day the wise Minos ruled Knossos and the Ægean. And of all the events which are at the back of these legends we know nothing. The hiéroglyphed tablets of the pre-Hellenic Greeks lie before us, but we cannot read them; we can only see that the Minoan writing in many ways resembled the Egyptian, thus again confirming our impression of the original early connection of the two cultures.

In view of this connection, and the known close relations between Crete and Egypt, from the end of the XIIth Dynasty to the end of the XVIIIth, we might have hoped to recover at Knossos a bilingual inscription in Cretan and Egyptian hieroglyphs which would give us the key to the Minoan script and tell us what we so dearly wish to know. But this hope has not yet been realized. Two Egyptian inscriptions have been found at Knossos, but no bilingual one. A list of Keftian names is preserved in the British Museum upon an Egyptian writing-board from Thebes with what is perhaps a copy of a single Cretan hieroglyph, a vase; but again, nothing bilingual. A list of "Keftian words" occurs at the head of a papyrus, also in the British Museum, but they appear to be nonsense, a mere imitation of the sounds of a strange tongue. Still we need not despair of finding the much desired Cretan-Egyptian bilingual inscription yet. Perhaps the double text of a treaty between Crete and Egypt, like that of Ramses II with the Hittites, may come to light. Meanwhile we can only do our best with the means at our hand to trace out the history of the relations of the oldest European culture with the ancient civilization of Egypt. The tomb-paintings at Thebes are very important material. Eor it is due to them that the voice of the doubter has finally ceased to be heard, and that now no archaeologist questions that the Egyptians were in direct communication with the Cretan Mycenæans in the time of the XVIIIth Dynasty, some fifteen hundred years before Christ, for no one doubts that the pictures of the Keftiu are pictures of Mycenaeans.

As we have seen, we know that this connection was far older than the time of the XVIIIth Dynasty, but it is during that time and the Hyksos period that we have the clearest documentary proof of its existence, from the statuette of Abnub and the alabastron lid of King Khian, found at Knossos, down to the Mycenaean pottery fragments found at Tell el-Amarna, a site which has been utterly abandoned since the time of the heretic Akhunaten (B.C. 1430), so that there is no possibility of anything found there being later than his time. That the connection existed as late as the time of the XXth Dynasty we know from the representations of golden Bügelkannen or false-necked vases of Mycenaean form in the tomb of Ramses III in the Bibân el-Mulûk, and of golden cups of Vaphio type in the tomb of Imadua, already mentioned. This brings the connection down to about 1050 B.C.

After that date we cannot hope to find any certain evidence of connection, for by that time the Mycenaean civilization had probably come to an end. In the days of the XIIth and XVIIIth Dynasties a great and splendid power evidently existed in Crete, and sent its peaceful ambassadors, the Keftiu who are represented in the Theban tombs, to Egypt. But with the XIXth Dynasty the name of the Keftiu disappears from Egyptian records, and their place is taken by a congeries of warring seafaring tribes, whose names as given by the Egyptians seem to be forms of tribal and place names well known to us in the Greece of later days. We find the Akaivasha (Axaifol, Achaians), Shakalsha (Sagalassians of Pisidia), Tursha (Tylissians of Crete?), and Shardana (Sardians) allied with the Libyans and Mashauash (Maxyes) in a land attack upon Egypt in the days of Meneptah, the successor of Ramses II—just as in the later days of the XXVIth Dynasty the Northern pirates visited the African shore of the Mediterranean, and in alliance with the predatory Libyans attacked Egypt.

Prof. Petrie has lately [History of Egypt, iii, pp. Ill, I12.] proffered an alternative view, which would make all these tribes Tunisians and Algerians, thus disposing of the identification of the Akaivasha with the Achaians, and making them the ancient representatives of the town of el-Aghwat (Roman Agbia) in Tunis. But several difficulties might be pointed out which are in the way of an acceptance of this view, and it is probable that the older identifications with Greek tribes must still be retained, so that Meneptah's Akaivasha are evidently the ancient representatives of the Achai(v)ans, the Achivi of the Roman poets. The terminations sha and na, which appear in these names, are merely ethnic and locative affixes belonging to the Asianic language system spoken by these tribes at that time, to which the language of the Minoan Cretans (which is written in the Knossian hieroglyphs) belonged. They existed in ancient Lycian in the forms azzi and nna, and we find them enshrined in the Asia Minor place-names terminating in assos and nda, as Halikarnassos, Sagalassos (Shakalasha in Meneptah's inscription), Oroanda, and Labraunda (which, as we have seen, is the same as the [Greek word], a word of pre-Hellenic origin, both meaning "Place of the Double Axe") The identification of these sha and nal terminations in the Egyptian transliterations of the foreign names, with the Lycian affixes referred to, was made some five years ago,* and is now generally accepted. We have, then, to find the equivalents of these names, to strike off the final termination, as in the case of Akaiva-sha, where Akaiva only is the real name, and this seems to be the Egyptian equivalent of Axaifol, Achivi. It is strange to meet with this great name on an Egyptian monument of the thirteenth century B.C. But yet not so strange, when we recollect that it is precisely to that period that Greek legend refers the war of Troy, which was an attack by Greek tribes from all parts of the Ægean upon the Asianic city at Hissarlik in the Troad, exactly parallel to the attacks of the Northerners on Egypt. And Homer preserves many a reminiscence of early Greek visits, peaceful and the reverse, to the coast of Egypt at this period. The reader will have noticed that one no longer treats the siege of Troy as a myth. To do so would be to exhibit a most uncritical mind; even the legends of King Arthur have a historic foundation, and those of the Nibelungen are still more probable.

* See Hall, Oldest Civilization of Greece, p. 178/.

In the eighth year of Ramses III the second Northern attack was made, by the Pulesta (Pelishtim, Philistines), Tjakaray, Shakalasha (Sagalassians), Vashasha, and Danauna or Daanau, in alliance with North Syrian tribes. The Danauna are evidently the ancient representatives of the Aavaoî, the Danaans who formed the bulk of the Greek army against Troy under the leadership of the long-haired Achaians, [Greek words] (like the Keftiu). The Vashasha have been identified by the writer with the Axians, the [Greek word] of Crete. Prof. Petrie compares the name of the Tjakaray with that of the (modern) place Zakro in Crete. Identifications with modern place-names are of doubtful value; for instance, we cannot but hold that Prof. Petrie errs greatly in identifying the name of the Pidasa (another tribe mentioned in Ramses II's time) with that of the river Pidias in Cyprus. "Pidias" is a purely modern corruption of the ancient Pediseus, which means the "plain-river" (because it flows through the central plain of the island), from the Greek [Greek word]. If, then, we make the Pidasa Cypriotes we assume that pure Greek was spoken in Cyprus as early as 1100 b. c, which is highly improbable. The Pidasa were probably Le-leges (Pedasians); the name of Pisidia may be the same, by metathesis. Pedasos is a name always connected with the much wandering tribe of the Leleges, where-ever they are found in Lakonia or in Asia Minor. We believe them to have been known to the Egyptians as Pidasa. The identification of the Tjakaray with Zakro is very tempting. The name was formerly identified with that of the Teukrians, but the v in the word Tewpot lias always been a stumbling-block in the way. Perhaps Zakro is neither more nor less than the Tetkpoc-name, since the legendary Teucer, the archer, was connected with the eastern or Eteokretan end of Crete, where Zakro lies. In Mycenæan times Zakro was an important place, so that the Tjakaray may be the Teukroi, after all, and Zakro may preserve the name. At any rate, this identification is most alluring and, taken in conjunction with the other cumulative identifications, is very probable; but the identification of the Pidæa with the river Pediæus in Cyprus is neither alluring nor probable.

In the time of Ramses II some of these Asia Minor tribes had marched against Egypt as allies of the Hittites. We find among them the Luka or Lycians, the Dardenui (Dardanians, who may possibly have been at that time in the Troad, or elsewhere, for all these tribes were certainly migratory), and the Masa (perhaps the Mysians). With the Cretans of Ramses Ill's time must be reckoned the Pulesta, who are certainly the Philistines, then most probably in course of their traditional migration from Crete to Palestine. In Philistia recent excavations by Mr. Welch have disclosed the unmistakable presence of a late Mycenæan culture, and we can only ascribe this to the Philistines, who were of Cretan origin.

Thus we see that all these Northern tribal names hold together with remarkable persistence, and in fact refuse to be identified with any tribes but those of Asia Minor and the Ægean. In them we see the broken remnants of the old Minoan (Keftian) power, driven hither and thither across the seas by intestinal feuds, and "winding the skein of grievous wars till every man of them perished," as Homer says of the heroes after the siege of Troy. These were in fact the wanderings of the heroes, the period of Sturm und Drang which succeeded the great civilized epoch of Minos and his thalassocracy, of Knossos, Phaistos, and the Keftius. On the walls of the temple of Medînet Habû, Ramses III depicted the portraits of the conquered heroes who had fallen before the Egyptian onslaught, and he called them heroes, tuher in Egyptian, fully recognizing their Berserker gallantry. Above all in interest are the portraits of the Philistines, those Greeks who at this very time seized part of Palestine (which takes its name from them), and continued to exist there as a separate people (like the Normans in France) for at least two centuries. Goliath the giant was, then, a Greek; certainly he was of Cretan descent, and so a Pelasgian.

Such are the conclusions to which modern discovery in Crete has impelled us with regard to the pictures of the Keftiu at Shêkh 'Abd el-Kûrna. It is indeed a new chapter in the history of the relations of ancient Egypt with the outside world that Dr. Arthur Evans has opened for us. And in this connection some American work must not be overlooked. An expedition sent out by the University of Pennsylvania, under Miss Harriet Boyd, has discovered much of importance to Mycenæan study in the ruins of an ancient town at Gournia in Crete, east of Knossos. Here, however, little has been found that will bear directly on the question of relations between Mycenaean Greece and Egypt.

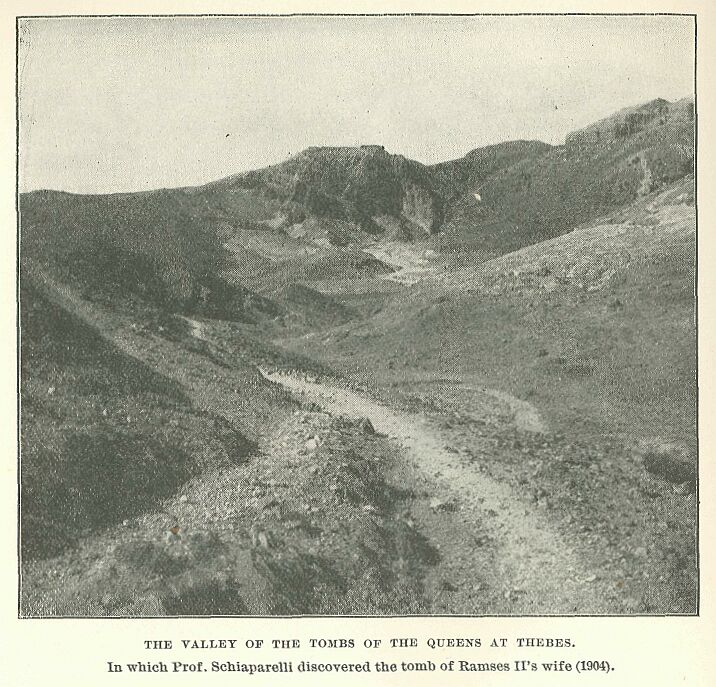

The Theban nécropoles of the New Empire are by no means exhausted by a description of the Tombs of the Kings and Shêkh 'Abd el-Kûrna; but few new discoveries have been made anywhere except in the picturesque valley of the Tombs of the Queens, south of Shêkh 'Abd el-Kûrna. Here the Italian Egyptologist, Prof. Schiaparelli, has lately discovered and excavated some very fine tombs of the XIXth and XXth Dynasties. The best is that of Queen Nefertari, one of the wives of Ramses II. The colouring of the reliefs upon these walls is extraordinarily bright, and the portraits of the queen, who has a very beautiful face, with aquiline nose, are wonderfully preserved. She was of the dark type, while another queen, Titi by name, who was buried close by, was fair, and had a retroussé nose. Prof. Schiaparelli also discovered here the tombs of some princes of the XXth Dynasty, who died young. All the tombs are much alike, with a single short gallery, on the walls of which are mythological scenes, figures of the prince and of his father, the king, etc., painted in a crude style, which shows a great degeneration from that of the XVIIIth Dynasty tombs.

We now leave the great necropolis and turn to the later temples of the Western Bank at Thebes. These were of a funerary character, like those of Dêr el-Bahari, already described. The most imposing of all in some respects is the Ramesseum, where lies the huge granite colossus of Ramses II, prostrate and broken, which Diodorus knew as the statue of Osymandyas. This name is a late corruption of Ramses II's throne-name, User-maat-Rà, pronounced Ûsimare. The temple has been cleared by Mr. Howard Carter for the Egyptian government, and the small town of priests' houses, magazines, and cellars, to the west of it, has been excavated by him. This is quite a little Pompeii, with its small streets, its houses with the stucco still clinging to the walls, its public altar, its market colonnade, and its gallery of statues. The statues are only of brick like the walls, and roughly shaped and plastered, but they were portraits, undoubtedly, of celebrities of the time, though we do not know of whom. On either side are the long magazines in which were kept the possessions of the priests of the Ramesseum, the grain from the lands with which they were endowed, and everything meet to be offered to the ghost of the king whom they served. The plan of the place had evidently been altered after the time of Ramses II, as remains of overbuilding were found here and there. The magazines were first investigated in 1896 by Prof. Petrie, who also found in the neighbourhood the remains of a number of small royal funerary temples of the XVIIIth Dynasty, all looking in the direction of the hill, beyond which lay the tombs of the kings.

In which Prof. Schiaparelli discovered the tomb of Ramses

II's wife (1904).

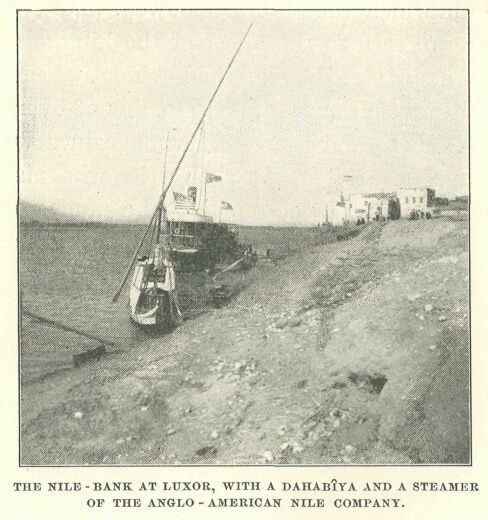

We may now turn to Luxor, where immediately above the landing-place of the steamers and dahabiyas rise the stately coloured colonnades of the Temple of Luxor. Unfortunately, modern excavations have not been allowed to pursue their course to completion here, as in the first great colonnaded court, which was added by Ramses II to the original building of Amenhetep III, Tutankhamen, and Horemheb, there still remains the Mohammedan Mosque of Abu-'l-Haggâg, which may not be removed. Abu-'l-Haggâg, "the Father of Pilgrims" (so called on account of the number of pilgrims to his shrine), was a very holy shêkh, and his memory is held in the greatest reverence by the Luksuris. It is unlucky that this mosque was built within the court of the Great Temple, and it cannot be removed till Moslem religious prejudices become at least partially ameliorated, and then the work of completely excavating the Temple of Luxor may be carried out.

Between Luxor and Karnak lay the temple of the goddess Mut, consort of Amen and protectress of Thebes. It stood in the part of the city known as Asheru. This building was cleared in 1895 at the expense and under the supervision of two English ladies, Miss Benson and Miss Gourlay.

With A Dahabîya And A Steamer Of The Anglo-American Nile

Company.