The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 1, Complete, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 1, Complete Author: Various Release Date: December 4, 2005 [EBook #17216] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, VOLUME 1 *** Produced by Syamanta Saikia, Jon Ingram, Barbara Tozier and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net Redesigned by David Widger converting original external links to internal links.[pg i]

This Guffawgraph is intended to form a refuge for destitute wit—an asylum for the thousands of orphan jokes—the superannuated Joe Millers—the millions of perishing puns, which are now wandering about without so much as a shelf to rest upon! It is also devoted to the emancipation of the JEW d’esprits all over the world, and the naturalization of those alien JONATHANS, whose adherence to the truth has forced them to emigrate from their native land.

has the honour of making his

appearance every SATURDAY, and continues, from week to week, to

offer to the world all the fun to be found in his own and the

following heads:

has the honour of making his

appearance every SATURDAY, and continues, from week to week, to

offer to the world all the fun to be found in his own and the

following heads:

“PUNCH” has no party prejudices—he is conservative in his opposition to Fantoccini and political puppets, but a progressive whig in his love of small change.

This department is conducted by Mrs. J. Punch, whose extensive acquaintance with the élite of the areas enables her to furnish the earliest information of the movements of the Fashionable World.

This portion of the work is under the direction of an experienced nobleman—a regular attendant at the various offices—who from a strong attachment to “PUNCH,” is frequently in a position to supply exclusive reports.

[pg iv]To render this branch of the periodical as perfect as possible, arrangements have been made to secure the critical assistance of John Ketch, Esq., who, from the mildness of the law, and the congenial character of modern literature with his early associations, has been induced to undertake its execution.

Anxious to do justice to native talent, the criticisms upon Painting, Sculpture, &c., are confided to one of the most popular artists of the day—“Punch’s” own immortal scene-painter.

These are amongst the most prominent features of the work. The Musical Notices are written by the gentleman who plays the mouth-organ, assisted by the professors of the drum and cymbals. “Punch” himself does the Drama.

A Prophet is engaged! He foretells not only the winners of each race, but also the “VATES” and colours of the riders.

Are contributed by the members of the following learned bodies:—

THE COURT OF COMMON COUNCIL AND THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY:—THE TEMPERANCE ASSOCIATION AND THE WATERPROOFING COMPANY:—THE COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS AND THE HIGHGATE CEMETERY:—THE DRAMATIC AUTHORS’ AND THE MENDICITY SOCIETIES:—THE BEEFSTEAK CLUB AND THE ANTI-DRY-ROT COMPANY.

Together with original, humorous, and satirical articles in verse and prose, from all the

Early in the month of July, 1841, a small handbill was freely distributed by the newsmen of London, and created considerable amusement and inquiry. That handbill now stands as the INTRODUCTION to this, the first Volume of Punch, and was employed to announce the advent of a publication which has sustained for nearly twenty years a popularity unsurpassed in the history of periodical literature. Punch and the Elections were the only matters which occupied the public mind on July 17, 1842. The Whigs had been defeated in many places where hitherto they had been the popular party, and it was quite evident that the Meeting of Parliament would terminate their lease of Office. [Street Politics.] The House met on the 19th of August, and unanimously elected MR. SHAW LEFEVRE to be Speaker. The address on the QUEEN’S Speech was moved by MR. MARK PHILLIPS, and seconded by MR. DUNDAS. MR. J.S. WORTLEY moved an amendment, negativing the confidence of the House in the Ministry, and the debate continued to occupy Parliament for four nights, when the Opposition obtained a majority of 91 against the Ministers. Amongst those who spoke against the Government, and directly in favour of SIR ROBERT PEEL, was MR. DISRAELI. In his speech he accused the Whigs of seeking to retain power in opposition to the wishes of the country, and of profaning the name of the QUEEN at their elections, as if she had been a second candidate at some petty poll, and considered that they should blush for the position in which they had placed their Sovereign. MR. BERNAL, Jun., retorted upon MR. DISRAELI for inveighing against the Whigs, with whom he had formerly been associated. SIR ROBERT PEEL, in a speech of great eloquence, condemned the inactivity and feebleness of the existing Government, and promised that, should he displace it, and take office, it should be by walking in the open light, and in the direct paths of the constitution. He would only accept power upon his conception of public duty, and would resign the moment he was satisfied he was unsupported by the confidence of the people, and not continue to hold place when the voice of the country was against him. [Hercules tearing Theseus from the Rock to which he had grown.] LORD JOHN defended the acts of the Ministry, and denied that they had been guilty of harshness to the poor by the New Poor Law, or enemies of the Church by reducing “the ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY to the miserable pittance of £15,000 a year, cutting down the BISHOP OF LONDON to no more than £10,000 a year, and the BISHOP OF DURHAM to the wretched stipend of £8,000 a year!” He twitted PEEL for his reticence upon the Corn Laws, and denounced the possibility of a sliding scale of duties upon corn. He concluded by saying, “I am convinced that, if this country be governed by enlarged and liberal counsels, its power and might will spread and increase, and its influence become greater and greater; liberal principles will prevail, civilisation will be spread to all parts of the globe, and you will bless millions by your acts and mankind by your union.” Loud and continued cheering followed this speech, but on division the majority was against the Ministers. When the House met to recommend the report on the amended Address, MR. SHARMAN CRAWFORD moved another amendment, to the effect that the distress of the people referred to in the QUEEN’S Speech was mainly attributable to the non-representation of the working classes in Parliament. He did not advocate universal suffrage, but one which would give a fair representation of the people. From the want of this arose unjust wars, unjust legislation, unjust monopoly, of which the existing Corn Laws were the most grievous instance. There was no danger in confiding the suffrage to the working classes, who had a vital interest in the public prosperity, and had evinced the truest zeal for freedom.

The amendment was negatived by 283 to 39.

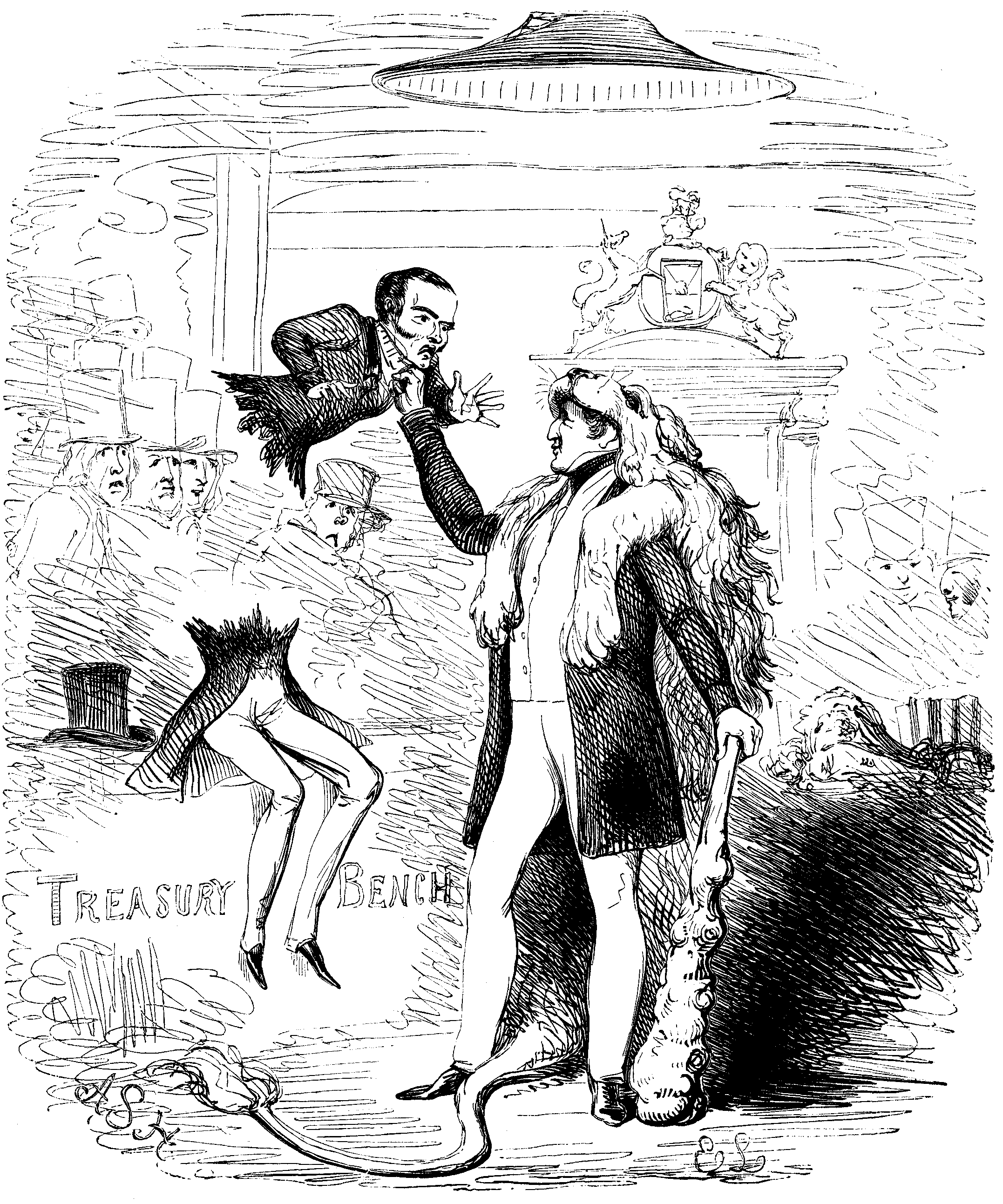

At the next meeting of the House LORD MARCUS HILL read the Answer to the Address, in which the QUEEN declared that “ever anxious to listen to the advice of Parliament, she would take immediate measures for the formation of a new Administration.” [Punch and Peel.] LORD MELBOURNE, in the House of Lords, announced on the 30th of August that he and his colleagues only held office until their successors were appointed. [Last Pinch.] The House received the announcement in perfect silence, and adjourned immediately afterwards. On the same [pg vi]night, in the House of Commons, LORD JOHN RUSSELL made a similar announcement, and briefly defended the course he and his colleagues had taken, and in reply to some complimentary remarks from LORD STANLEY, approving of LORD JOHN’S great zeal, talent, and perseverance, denied that the Crown was answerable for any of the propositions contained in the Speech, which were the result of the advice of HER MAJESTY’S Ministers, and for which her Ministers alone were responsible. This declaration was necessary in consequence of the accusation of the Conservatives, that the Ministry had made an unfair use of the QUEEN’S name in and out of Parliament. [Trimming a Whig.] The new Ministry [The Letter of Introduction] was formed as follows:—

THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON (without office); First Lord of the Treasury, SIR R. PEEL; Lord Chancellor, LORD LYNDHUHST; Chancellor of the Exchequer, RIGHT HON. H. GOULBURN; President of the Council, LORD WHARNCLIFFE; Privy Seal, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM; Home Secretary, SIR JAMES GRAHAM; Foreign Secretary, EARL OF ABERDEEN; Colonial Secretary, LORD STANLEY; First Lord of the Admiralty, EARL OF HADDINGTON; President of the Board of Control, LORD ELLENBOROUGH; President of the Board of Trade, EARL OF RIPON; Secretary at War, SIR H. HARDINGE; Treasurer of the Navy and Paymaster of the Forces, SIR E. KNATCHBULL.

Postmaster-General, LORD LOWTHER; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, LORD G. SOMERSET; Woods and Forests, EARL OF LINCOLN; Master-General of the Ordnance, SIR G. MURRAY; Vice-President of the Board of Trade and Master of the Mint, W.E. GLADSTONE; Secretary of the Admiralty, HON. SYDNEY HERBERT; Joint Secretaries of the Treasury, SIR G. CLERK and SIR T. FREMANTLE; Secretaries of the Board of Control, HON. W. BARING and J. EMERSON TENNENT; Home Under-Secretary, HON. C.M. SUTTON; Foreign Under-Secretary, LORD CANNING; Colonial Under-Secretary, G.W. HOPE; Lords of the Treasury, ALEXANDER PRINGLE, H. BARING, J. YOUNG, and J. MILNES GASKELL; Lords of the Admiralty, SIR G. COCKBURN, ADMIRAL SIR W. GAGE, SIR G. SEYMOUR, HON. CAPTAIN GORDON, HON. H.L. COREY; Store-keeper of the Ordnance, J.R. BONHAM; Clerk of the Ordnance, CAPTAIN BOLDERO; Surveyor-General of the Ordnance, COLONEL JONATHAN PEEL; Attorney-General, SIR F. POLLOCK; Solicitor-General, SIR W. FOLLETT; Judge-Advocate, DR. NICHOLL; Governor-General of Canada, SIR C. BAGOT; Lord Advocate of Scotland, SIR W. RAE.

Lord Lieutenant, EARL DE GREY; Lord Chancellor, SIR E. SUGDEN; Chief Secretary, LORD ELIOT; Attorney-General, MR. BLACKBURNE, Q.C.; Solicitor-General, SERJEANT JACKSON.

Lord Chamberlain, EARL DELAWARR; Lord Steward, EARL OF LIVERPOOL; Master of the Horse, EARL OF JERSEY; Master of the Buckhounds, EARL OF ROSSLYN; Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard, MARQUIS OF LOTHIAN; Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners, LORD FORESTER; Vice-Chamberlain, LORD ERNEST BRUCE; Treasurer of the Household, EARL JERMYN; Controller of the Household, HON. D. DAMER; Lords in Waiting, LORD ABOYNE, LORD RIVERS, LORD HARDWICKE, LORD BYRON, EARL OF WARWICK, VISCOUNT SYDNEY, EARL OF MORTON, and MARQUIS OF ORMONDE; Groom in Waiting, CAPTAIN MEYNELL; Mistress of the Robes, DUCHESS OF BUCCLEUCH; Ladies of the Bedchamber, MARCHIONESS CAMDEN, LADY LYTTELTON, LADY PORTMAN, LADY BARHAM, and COUNTESS OF CHARLEMONT.

Groom of the Stole, MARQUIS OF EXETER; Sergeant-at-Arms, COLONEL PERCEVAL; Clerk Marshal, LORD C. WELLESLEY.

The members of the new Government were re-elected without an exception, and the House of Commons met again on September 16. SIR ROBERT PEEL made a statement to the House, in which he merely intimated that he should adopt the Estimates [Playing the Knave] of his predecessors, and continue the existing Poor-Law and its Establishment to the 31st of July following. He declined to announce his own financial measures until the next Session, and continued in this determination unmoved by the speeches of LORD JOHN RUSSELL, LORD PALMERSTON, and other Members of the Opposition. MR. FIELDEN moved that no supplies be granted until after an inquiry into the distress of the country; but the motion was negatived by a large majority. Continual reference was made by MR. COBDEN, MR. VILLIERS, and others to the strong desire of the people for a Repeal of the Corn Laws, and which had been loudly expressed out of the House for more than four years. MR. BUSFIELD FERRAND denied the necessity for any alteration, and accused the manufacturers of fomenting the agitation for their own selfish ends, and to increase their power of reducing the wages of the already starving workmen. MR. MARK PHILLIPS, in a capital speech, disproved all MR. FERRAND’S statements. SIR ROBERT PEEL brought in a Bill to continue the Poor Law Commission for six months, and MR. FIELDER’S Amendment [The Well Dressed and the Well to Do] to reject it was negatived by 183 to 18. LORD MELBOURNE attacked, in the House of Lords, the Ministerial plan of finance, and their silence as to the future [Mr. Sancho Bull and his State Physician], and invited the DUKE OF WELLINGTON to bring forward a measure for an alteration of the Corn Laws, promising him a full House if he would do so. The Duke declined the invitation, as he never announced an intention which he did not entertain, and he had not considered the operation of the Corn Laws sufficiently to bring forward a scheme for the alteration of them. This statement led on a subsequent evening to an intimation from the DUKE OF WELLINGTON, in reply to the EARL OF RADNOR, that a consideration of the Corn Laws was only declined “at the present time.” On the 7th of October Parliament was prorogued until November 11th, the Lords Commissioners being the LORD CHANCELLOR, the DUKE OF WELLINGTON, the DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM, the EARL OF SHAFTESBURY, and LORD WHARNCLIFFE.

Hume’s Terminology.—Defeat at Leeds.

| W. BECKETT | 2076 |

| W. ALDAM | 2043 |

| T. HUME | 2033 |

| VISCOUNT JOCELYN | 1926 |

Lessons in Punmanship.—THOMAS HOOD, the distinguished Poet and Wit, died May 3, 1845.

Court Circular.—MASTER JONES, better known as the “Boy JONES,” was a sweep who obtained admission on more than one occasion to Buckingham Palace in a very mysterious manner. He gave great trouble to the authorities, and was at length sent into the Royal Navy.

Mrs. Lilly was the nurse of the PRINCESS ROYAL.

Mr. Moreton Dyer, a stipendiary Magistrate, removed from the Commons on a charge of bribing electors.

A Public Conveyance.—THE MARQUIS OF WATERFORD was then a man about town, and frequently before the public in connection with some extravagance.

“The Black-Balled Of The United Service” refers to proceedings connected with the EARL OF CARDIGAN. Exception had been taken to the introduction of black bottles at the mess-table at Brighton, and a duel was subsequently fought by LORD CARDIGAN and MR. HARVEY TUCKETT.

An Ode.—Kilpack’s Divan, now the American Bowling Alley, in King Street, Covent Garden, continues to be the resort of minor celebrities. As the club was a private one, we do not feel justified in more plainly indicating the members referred to as the “jocal nine.”

Mrs. H.—MRS. HONEY, a very charming actress.

Court Circular.—DEAF BURKE was a pugilist who occasionally exhibited himself as “the Grecian Statues,” and upon one occasion attempted a reading from SHAKSPEARE. As he was very ignorant, and could neither read nor write, the effect was extremely ridiculous, and helped to give the man a notoriety.

The Harp, a tavern near Drury Lane, was a favourite resort of the Elder KEAN, and in 1841 had a club-room divided into four wards: Gin Ward, Poverty Ward, Insanity Ward, and Suicide Ward, the walls of which were appropriately illustrated, and by no mean hand. The others named (with the exception of PADDY GREEN) were pugilists.

An an-tea Anacreontic.—RUNDEL was the head of a large Jeweller’s firm on Ludgate Hill.

Monsieur Jullien was the first successful promoter of cheap concerts in England. He was a clever conductor, and affected the mountebank. He was a very honourable man, and hastened his death by over-exertion to meet his liabilities. He died 1860.

Punch and Peel.—SIR ROBERT PEEL stipulated, on taking office, for an entire change of the Ladies of the Bedchamber.

William Farren, the celebrated actor of Old Men.

Colonel Sibthorp was M.P. for Lincoln, and more distinguished by his benevolence to his constituency than his merits as a senator. He was very amusing.

Fashionable Movements.—COUNT D’ORSAY, an elegant, accomplished, and kind-hearted Frenchman, was a leader of Fashion, long resident in England. He was the friend and adviser of Louis NAPOLEON during his exile in this country. COUNT D’ORSAY died in Paris.

Jobbing Patriots.—MR. GEORGE ROBINS was an auctioneer in Covent Garden, and celebrated for the extravagant imagery of his advertisements. His successors have offices in Bond Street.

Shocking Want of Sympathy.—SIR P. LAURIE, a very active City magnate, continually engaged in “putting down” suicide, poverty, &c.

Sir F. Burdett, long the Radical member for Westminster. His political perversion took every one by surprise.

New Stuffing for the Speaker’s Chair.—MR. PETER BORTHWICK had been an actor in the Provinces.

Inquest.—The Eagle Tavern, City Road, was built by MR. ROUSE—“Bravo, ROUSE!” as he was called.

Lady Morgan, the Authoress of The Wild Irish Girl, and many other popular works, died 1860.

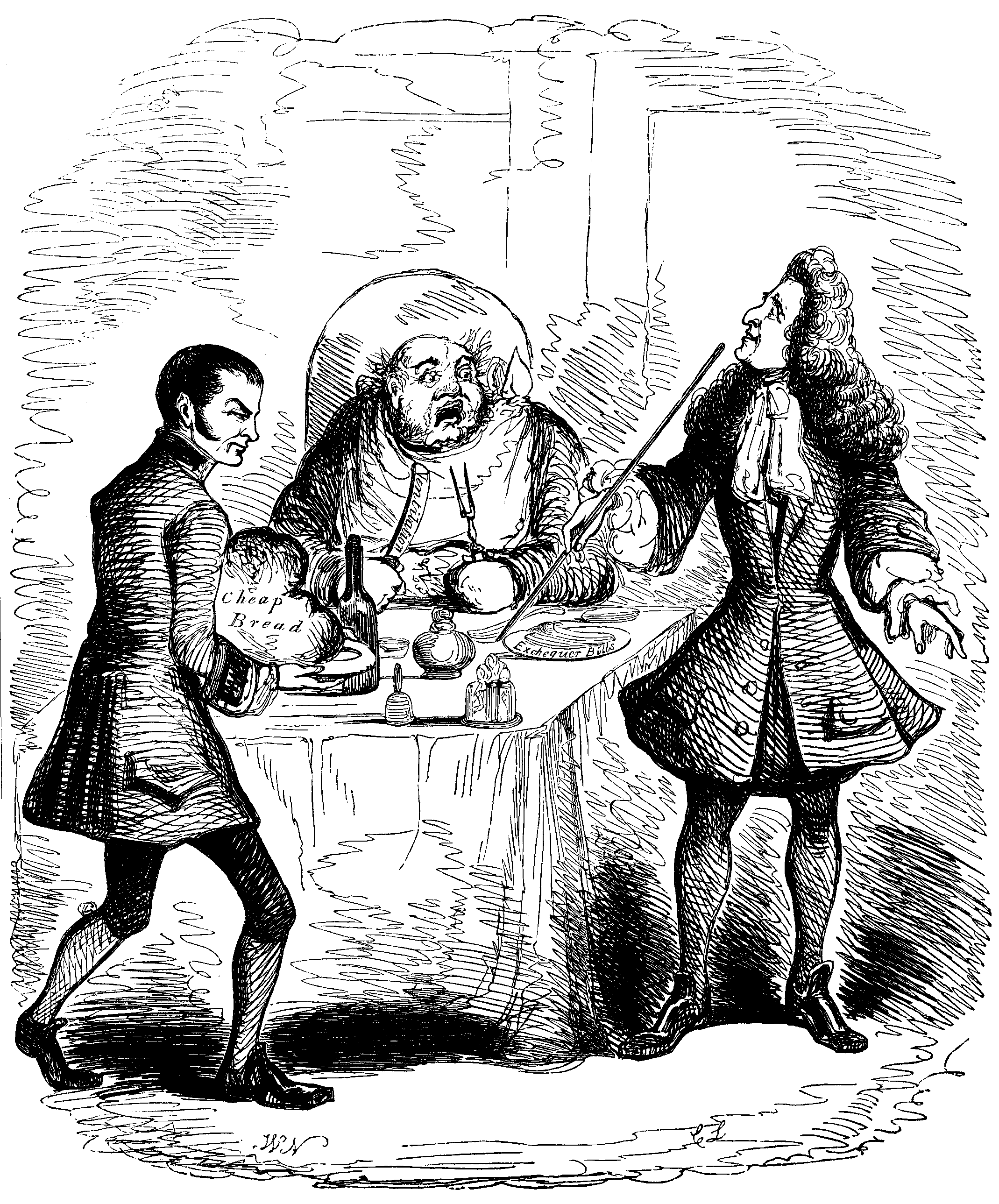

The Tory Table d’Hote.—“BILLY” HOLMES was whipper-in to the Conservatives in the House of Commons.

The Legal Eccalobeion.—BARON CAMPBELL had been appointed Chancellor of Ireland a few days before the Dissolution (1841). He is now Lord Chancellor of England (1861). The Eccalobeion was an apparatus for hatching birds by steam, but was too costly to be successful commercially.

The State Doctor.—SIR R. PEEL, in his speech at Tamworth, had called himself “the State Doctor,” who would not attempt to prescribe until regularly called in.

Curious Coincidence.—Certain gentlemen, feeling themselves aggrieved and unfairly treated by the managers of the London Theatres, had for some time been abusing the more fortunate dramatists, whose pieces had found acceptance with the public, until at last they resolved upon the course here set forth, and commented upon.

Animal Magnetism.—LORDS MELBOURNE, RUSSELL, and MORPETH, and MR. LABOUCHERE at the window, SIR R. PEEL and the DUKE OF WELLINGTON mesmerising the Lion.

Mr. Muntz, M.P. for Birmingham, wore a very large beard, and in 1841 such hirsute adornments were very uncommon.

General Satisfaction.—The Morning Herald had acquired the sobriquet of “My Grandmother.”

Done Again.—MR. DUNN, a barrister, subjected Miss BURDETT COUTTS to a series of annoyances which ultimately led to legal proceedings, and to MR. DUNN’S imprisonment.

Bernard Cavanagh was an impostor who pretended he could live for many weeks without food. He attracted much attention at the time, and was ultimately detected concealing [pg viii]a cold sausage, when he confessed his imposture, and was imprisoned by the MAYOR OF READING.

Taking The Hodds.—“Holy Land,” the cant name for a part of St. Giles’s, now destroyed. BANKS owned a public-house frequented by thieves of both sexes, and whom he managed to keep under perfect control. A visit to “Stunning JOE BANKS” was thought a fast thing in 1841.

Feargus O’Connor, M.P. for Nottingham, was the leader of the Chartists and projector of the Land Scheme for securing votes to the masses. The project failed. MR. O’CONNOR was a political enthusiast, ultimately became insane, and died in an Asylum.

Die Hexen am Rhein.—MR. FREDERICK YATES was an admirable actor, and the proprietor and manager of the favourite “little Adelphi” Theatre, in the Strand.

Prospectus.—We believe this article suggested the existing Accident Assurance Company.

Mr. Silk Buckingham was a voluminous writer and founder of the British and Foreign Institute, in George Street, Hanover Square.

Parliamentary Masons.—The masons employed in building the New Houses of Parliament struck for higher wages.

The Improvident.—LORD MELBOURNE and MR. LABOUCHERE, MR. D. O’CONNELL, LORDS RUSSELL and MORPETH.

Promenade Concerts.—M. MUSARD was the originator in Paris of this class of amusement. Their popularity induced an imitation in England by M. JULLIEN.

To Benevolent and Humane Jokers.—TOM COOKE was the leader and composer at the Theatres Royal, and a remarkable performer on a penny trumpet. He occasionally made use of this toy in his pantomime introductions. He was also a very “funny” fellow.

Coming Events Cast their Shadows before.—SIR JAMES CLARKE, Accoucheur to the QUEEN.

Savory Con. by Cox.—COX AND SAVORY, advertising silversmiths and watchmakers.

New Parliamentary Masons.—In the foreground COL. SIBTHORP, SIR R. PEEL, and MR. O’CONNELL. At the back SIR JAMES GRAHAM, DUKE OF WELLINGTON, and LORD STANLEY.

“Rob Me the Exchequer, Hal.”—A person of the name of SMITH forged a great amount of Exchequer Bills at this time.

The Fire at the Tower on October 31, 1841. Immense damage was done to the building, and a great quantity of arms were destroyed. (See Annual Register.)

Sir Robert Macaire.—Robert Macaire was a French felonious drama made famous by the admirable acting of LEMAITRE, and, from some supposed allusion to LOUIS PHILIPPE, MACAIRE’S friend and scapegoat always appears with a large umbrella.

The O’Connell Papers.—D. O’CONNELL was elected Lord Mayor of Dublin, 1841.

Harmer Virumque Cano.—ALDERMAN HARMER, Proprietor of the Weekly Dispatch, and for that and other reasons, was not elected Lord Mayor.

Cutting at the Root of the Evil.—MR. HOBLER was for many years Principal Clerk to the Magistrates at the Mansion House.

Olivia’s (Lord Brougham’s) Return to her Friends.—LORDS RUSSELL, MELBOURNE, MORPETH, D. O’CONNELL, CORDEN, and LABOUCHERE.

A Barrow Knight.—SIR VINCENT COTTON was a well-known four-in-hand whip, and for some little time drove a coach to Brighton. SIR WYNDHAM ANSTRUTHER (WHEEL OF FORTUNE) was another four-in-hand celebrity.

Seeing Nothing.—DANIEL WHITTLE HARVEY.

Barber-ous Announcement.—MR. TANNER’S shop was part of one of the side arches of Temple Bar, and so reached from that obstruction to Shire Lane, which adjoins it on the City side.

Fashionable Intelligence.—The PADDY GREEN so frequently referred to was a popular singer and an excellent tempered man. He was unfairly treated by Punch at this time, because really unknown to the writer. MR. JOHN GREEN is now the well known and much respected host and proprietor of Evans’s Hotel, Covent Garden.

Kings and Carpenters.—DON LEON, shot for insurrection in favour of the Ex-Regent CHRISTINA.

Cupid out of Place.—LORD PALMERSTON, from his very engaging manner, was long known as “Cupid.”

Jack Cutting his Name on the Beam.—LORD JOHN RUSSELL, after GEORGE CRUIKSHANK’S etching of Jack Sheppard.

Sibthorp’s Con. Corner.—BRYANT was publisher of Punch, 1841.

As we hope, gentle public, to pass many happy hours in your society, we think it right that you should know something of our character and intentions. Our title, at a first glance, may have misled you into a belief that we have no other intention than the amusement of a thoughtless crowd, and the collection of pence. We have a higher object. Few of the admirers of our prototype, merry Master PUNCH, have looked upon his vagaries but as the practical outpourings of a rude and boisterous mirth. We have considered him as a teacher of no mean pretensions, and have, therefore, adopted him as the sponsor for our weekly sheet of pleasant instruction. When we have seen him parading in the glories of his motley, flourishing his baton (like our friend Jullien at Drury-lane) in time with his own unrivalled discord, by which he seeks to win the attention and admiration of the crowd, what visions of graver puppetry have passed before our eyes! Golden circlets, with their adornments of coloured and lustrous gems, have bound the brow of infamy as well as that of honour—a mockery to both; as though virtue required a reward beyond the fulfilment of its own high purposes, or that infamy could be cheated into the forgetfulness of its vileness by the weight around its temples! Gilded coaches have glided before us, in which sat men who thought the buzz and shouts of crowds a guerdon for the toils, the anxieties, and, too often, the peculations of a life. Our ears have rung with the noisy frothiness of those who have bought their fellow-men as beasts in the market-place, and found their reward in the sycophancy of a degraded constituency, or the patronage of a venal ministry—no matter of what creed, for party must destroy patriotism.

The noble in his robes and coronet—the beadle in his gaudy livery of scarlet, and purple, and gold—the dignitary in the fulness of his pomp—the demagogue in the triumph of his hollowness—these and other visual and oral cheats by which mankind are cajoled, have passed in review before us, conjured up by the magic wand of PUNCH.

How we envy his philosophy, when SHALLA-BA-LA, that demon with the bell, besets him at every turn, almost teasing the sap out of him! The moment that his tormentor quits the scene, PUNCH seems to forget the existence of his annoyance, and, carolling the mellifluous numbers of Jim Crow, or some other strain of equal beauty, makes the most of the present, regardless of the past or future; and when SHALLA-BA-LA renews his persecutions, PUNCH boldly faces his enemy, and ultimately becomes the victor. All have a SHALLA-BA-LA in some shape or other; but few, how few, the philosophy of PUNCH!

We are afraid our prototype is no favourite with the ladies. PUNCH is (and we reluctantly admit the fact) a Malthusian in principle, and somewhat of a domestic tyrant; for his conduct is at times harsh and ungentlemanly to Mrs. P.

“Eve of a land that still is Paradise,

Italian beauty!”

But as we never look for perfection in human nature, it is too much to expect it in wood. We wish it to be understood that we repudiate such principles and conduct. We have a Judy of our own, and a little Punchininny that commits innumerable improprieties; but we fearlessly aver that we never threw him out of window, nor belaboured the lady with a stick—even of the size allowed by law.

There is one portion of the drama we wish was omitted, for it always saddens us—we allude to the prison scene. PUNCH, it is true, sings in durance, but we hear the ring of the bars mingling with the song. We are advocates for the correction of offenders; but how many generous and kindly beings are there pining within the walls of a prison, whose only crimes are poverty and misfortune! They, too, sing and laugh, and appear jocund, but the heart can ever hear the ring of the bars.

We never looked upon a lark in a cage, and heard him trilling out his music as he sprang upwards to the roof of his prison, but we felt sickened with the sight and sound, as contrasting, in our thought, the free minstrel of the morning, bounding as it were into the blue caverns of the heavens, with the bird to whom the world was circumscribed. May the time soon arrive, when every prison shall be a palace of the mind—when we shall seek to instruct and cease to punish. PUNCH has already advocated education by example. Look at his dog Toby! The instinct of the brute has almost germinated into reason. Man has reason, why not give him intelligence?

We now come to the last great lesson of our motley teacher—the gallows! that accursed tree which has its root in injuries. How clearly PUNCH exposes the fallacy of that dreadful law which authorises the destruction of life! PUNCH sometimes destroys the hangman: and why not? Where is the divine injunction against the shedder of man’s blood to rest? None can answer! To us there is but ONE disposer of life. At other times PUNCH hangs the devil: this is as it should be. Destroy the principle of evil by increasing the means of cultivating the good, and the gallows will then become as much a wonder as it is now a jest.

We shall always play PUNCH, for we consider it best to be merry and wise—

“And laugh at all things, for we wish to know,

What, after all, are all things but a show!”—Byron.

As on the stage of PUNCH’S theatre, many characters appear to fill up the interstices of the more important story, so our pages will be interspersed with trifles that have no other object than the moment’s approbation—an end which will never be sought for at the expense of others, beyond the evanescent smile of a harmless satire.

There is a report of the stoppage of one of the most respectable hard-bake houses in the metropolis. The firm had been speculating considerably in “Prince Albert’s Rock,” and this is said to have been the rock they have ultimately split upon. The boys will be the greatest sufferers. One of them had stripped hia jacket of all its buttons as a deposit on some tom-trot, which the house had promised to supply on the following day; and we regret to say, there are whispers of other transactions of a similar character.

Money has been abundant all day, and we saw a half-crown piece and some halfpence lying absolutely idle in the hands of an individual, who, if he had only chosen to walk with it into the market, might have produced a very alarming effect on some minor description of securities. Cherries were taken very freely at twopence a pound, and Spanish (liquorice) at a shade lower than yesterday. There has been a most disgusting glut of tallow all the week, which has had an alarming effect on dips, and thrown a still further gloom upon rushlights.

The late discussions on the timber duties have brought the match market into a very unsettled state, and Congreve lights seem destined to undergo a still further depression. This state of things was rendered worse towards the close of the day, by a large holder of the last-named article unexpectedly throwing an immense quantity into the market, which went off rapidly.

Many of our readers must be aware, that in pantomimic pieces, the usual mode of making the audience acquainted with anything that cannot be clearly explained by dumb-show, is to exhibit a linen scroll, on which is painted, in large letters, the sentence necessary to be known. It so happened that a number of these scrolls had Been thrown aside after one of the grand spectacles at Astley’s Amphitheatre, and remained amongst other lumber in the property-room, until the late destructive fire which occurred there. On that night, the wife of one of the stage-assistants—a woman of portly dimensions—was aroused from her bed by the alarm of fire, and in her confusion, being unable to find her proper habiliments, laid hold of one of these scrolls, and wrapping it around her, hastily rushed into the street, and presented to the astonished spectators an extensive back view, with the words, “BOMBARD THE CITADEL,” inscribed in legible characters upon her singular drapery.

Hume is so annoyed at his late defeat at Leeds, that he vows he will never make use of the word Tory again as long as he lives. Indeed, he proposes to expunge the term from the English language, and to substitute that which is applied to, his own party. In writing to a friend, that “after the inflammatory character of the oratory of the Carlton Club, it is quite supererogatory for me to state (it being notorious) that all conciliatory measures will be rendered nugatory,” he thus expressed himself:—“After the inflammawhig character of the orawhig of the nominees of the Carlton Club, it is quite supererogawhig for me to state (it being nowhigous) that all conciliawhig measures will be rendered nugawhig.”

A correspondent to one of the daily papers has remarked, that there is an almost total absence of swallows this summer in England. Had the writer been present at some of the election dinners lately, he must have confessed that a greater number of active swallows has rarely been observed congregated in any one year.

My dear PUNCH,—Seeing in the “Court Circular” of the Morning Herald an account of a General Goblet as one of the guests of her Majesty, I beg to state, that till I saw that announcement, I was not aware of any other general gobble it than myself at the Palace.

Yours, truly,

MELBOURN

DEAR PUNCH,—I was much amused the other day, on taking my seat in the Birmingham Railway train, to observe a sentimental-looking young gentleman, who was sitting opposite to me, deliberately draw from his travelling-bag three volumes of what appeared to me a new novel of the full regulation size, and with intense interest commence the first volume at the title-page. At the same instant the last bell rang, and away started our train, whizz, bang, like a flash of lightning through a butter-firkin. I endeavoured to catch a glimpse of some familiar places as we passed, but the attempt was altogether useless. Harrow-on-the-Hill, as we shot by it, seemed to be driving pell-mell up to town, followed by Boxmoor, Tring, and Aylesbury—I missed Wolverton and Weedon while taking a pinch of snuff—lost Rugby and Coventry before I had done sneezing, and I had scarcely time to say, “God bless us,” till I found we had reached Birmingham. Whereupon I began to calculate the trifling progress my reading companion could have made in his book during our rapid journey, and to devise plans for the gratification of persons similarly situated as my fellow-traveller. “Why,” thought I, “should literature alone lag in the age of steam? Is there no way by which a man could be made to swallow Scott or bolt Bulwer, in as short a time as it now takes him to read an auction bill?” Suddenly a happy thought struck me: it was to write a novel, in which only the actual spirit of the narration should be retained, rejecting all expletives, flourishes, and ornamental figures of speech; to be terse and abrupt in style—use monosyllables always in preference to polysyllables—and to eschew all heroes and heroines whose names contain more than four letters. Full of this idea, on my returning home in the evening, I sat to my desk, and before I retired to rest, had written a novel of three neat, portable volumes; which, I assert, any lady or gentlemen, who has had the advantage of a liberal education, may get through with tolerable ease, in the time occupied by the railroad train running from London to Birmingham.

I will not dilate on the many advantages which this description of writing possesses over all others. Lamplighters, commercial bagmen, omnibus-cads, tavern-waiters, and general postmen, may “read as they run.” Fiddlers at the theatres, during the rests in a piece of music, may also benefit by my invention; for which, if the following specimen meet your approbation, I shall instantly apply for a patent.

Clare Grey—Sweet girl—Bloom and blushes, roses, lilies, dew-drops, &c.—Tom Lee—Young, gay, but poor—Loved Clare madly—Clare loved Tom ditto—Clare’s pa’ rich, old, cross, cruel, &c.—Smelt a rat—D—d Tom, and swore at Clare—Tears, sighs, locks, bolts, and bars—Love’s schemes—Billet-doux from Tom, conveyed to Clare in a dish of peas, crammed with vows, love, despair, hope—Answer (pencil and curl-paper), slipped through key-hole—Full of hope, despair, love, vows—Tom serenades—Bad cold—Rather hoarse—White kerchief from garret-window—“’Tis Clare! ’tis Clare!”—Garden-wall, six feet high—Love is rash—Scale the wall—Great house-dog at home—Pins Tom by the calf—Old Hunk’s roused—Fire! thieves! guns, swords, and rushlights—Tom caught—Murder, burglary—Station-house, gaol, justice—Fudge!—Pretty mess—Heigho!—‘Oh! ’tis love,’ &c.—Sweet Clare Grey!—Seven pages of sentiment—Lame leg, light purse, heavy heart—Pshaw!—Never mind—

“Adieu, my native land,” &c.—D.I.O.—“We part to meet again”—Death or glory—Red coat—Laurels and rupees in view—Vows of constancy, eternal truth, &c—Tom swells the brine with tears—Clare wipes her eyes in cambric—Alas! alack! oh! ah!—Fond hearts, doomed to part—Cruel fate!—Ten pages, poetry, romance, &c. &c.—Tom in battle—Cut, slash, dash—Sabres, rifles—Round and grape in showers—Hot work—Charge!—Whizz—Bang!—Flat as a Flounder—Never say die—Peace—Sweet sound—Scars, wounds, wooden leg, one arm, and one eye—Half-pay—Home—Huzza!—Swift gales—Post-horses—Love, hope, and Clare Grey—

“Here we are!”—At home once more—Old friends and old faces—Must be changed—Nobody knows him—Church bells ringing—Inquire cause—(?)—Wedding—Clare Grey to Job Snooks, the old pawnbroker—Brain whirls—Eyes start from sockets—Devils and hell—Clare Grey, the fond, constant, Clare, a jilt?—Can’t be—No go—Stump up to church—Too true—Clare just made Mrs. Snooks—Madness!! rage!!! death!!!!—Tom’s crutch at work—Snooks floored—Bridesman settled—Parson bolts—Clerk mizzles—Salts and shrieks—Clare in a swoon—Pa’ in a funk—Tragedy speech—Love! vengeance! and damnation!—Half an ounce of laudanum—Quick speech—Tom unshackles his wooden pin—Dies like a hero—Clare pines in secret—Hops the twig, and goes to glory in white muslin—Poor Tom and Clare! they now lie side by side, beneath

We have been favoured with the following announcement from Mr. Hood, which we recommend to the earnest attention of our subscribers:—

MR. T. HOOD, PROFESSOR OF PUNMANSHIP,

Begs to acquaint the dull and witless, that he has established a class for the acquirement of an elegant and ready style of punning, on the pure Joe-millerian principle. The very worst hands are improved in six short and mirthful lessons. As a specimen of his capability, he begs to subjoin two conundrums by Colonel Sibthorpe.

COPY.

“The following is a specimen of my punning before taking six lessons of Mr. T. Hood:—

“Q. Why is a fresh-plucked carnation like a certain cold with which children are affected?

“A. Because it’s a new pink off (an hooping-cough).

“This is a specimen of my punning after taking six lessons of Mr. T. Hood:—

“Q. Why is the difference between pardoning and thinking no more of an injury the same as that between a selfish and a generous man?

“A. Because the one is for-getting and the other for-giving.”

N.B. Gentlemen who live by their wits, and diners-out in particular, will find Mr. T. Hood’s system of incalculable service.

Mr. H. has just completed a large assortment of jokes, which will be suitable for all occurrences of the table, whether dinner or tea. He has also a few second-hand bon mots which he can offer a bargain.

∴ A GOOD LAUGHER WANTED.

There hath been long wanting a full and perfect Synopsis of Voting, it being a science which hath become exceedingly complicated. It is necessary, therefore, to the full development of the art, that it be brought into such an exposition, as that it may be seen in a glance what are the modes of bribing and influencing in Elections. The briber, by this means, will be able to arrange his polling-books according to the different categories, and the bribed to see in what class he shall most advantageously place himself.

It is true that there be able and eloquent writers greatly experienced in this noble science, but none have yet been able so to express it as to bring it (as we hope to have done) within the range of the certain sciences. Henceforward, we trust it will form a part of the public education, and not be subject tot he barbarous modes pursued by illogical though earnest and zealous disciples; and that the great and glorious Constitution that has done so much to bring it to perfection, will, in its turn, be sustained and matured by the exercise of what is really in itself so ancient and beautiful a practice.

Have any of PUNCH’S readers ever met one of the above genus—or rather, have they not? They must; for the race is imbued with the most persevering hic et ubique powers. Like the old mole, these Truepennies “work i’ th’ dark:” at the Theatres, the Opera, the Coal Hole, the Cider Cellars, and the whole of the Grecian, Roman, British, Cambrian, Eagle, Lion, Apollo, Domestic, Foreign, Zoological, and Mythological Saloons, they “most do congregate.” Once set your eyes upon them, once become acquainted with their habits and manners, and then mistake them if you can. They are themselves, alone: like the London dustmen, the Nemarket jockeys, the peripatetic venders, or buyers of “old clo’,” or the Albert continuations at one pound one, they appear to be made to measure for the same. We must now describe them (to speak theatrically) with decorations, scenes, and properties! The entirely new dresses of a theatre are like the habiliments of the professional singer, i.e. neither one nor the other ever were entirely new, and never will be allowed to grow entirely old. The double-milled Saxony of these worthies is generally very blue or very brown; the cut whereof sets a man of a contemplative turn of mind wondering at what precise date those tails were worn, and vainly speculating on the probabilities of their being fearfully indigestible, as that alone could to long have kept them from Time’s remorseless maw. The collars are always velvet, and always greasy. There is a slight ostentation manifested in the seams, the stitches whereof are so apparent as to induce the beholders to believe they must have been the handiwork of some cherished friend, whose labours ought not to be entombed beneath the superstructure. The buttons!—oh, for a pen of steam to write upon those buttons! They, indeed, are the aristocracy—the yellow turbans, the sun, moon, and stars of the woollen system! They have nothing in common with the coat—they are on it, and that’s all—they have no further communion—they decline the button-holes, and eschew all right to labour for their living—they announce themselves as “the last new fashion”—they sparkle for a week, retire to their silver paper, make way for the new comers, and, years after, like the Sleeping Beauty, rush to life in all their pristine splendour, and find (save in the treble-gilt aodication and their own accession) the coat, the immortal coat, unchanged! The waistcoat is of a material known only to themselves—a sort of nightmare illusion of velvet, covered with a slight tracery of refined mortar, curiously picked out and guarded with a nondescript collection of the very greenest green pellets of hyson-bloom gunpowder tea. The buttons (things of use in this garment) describe the figure and proportions of a large turbot. They consist of two rows (leaving imagination to fill up a lapse of the absent), commencing, to all appearance, at the small of the back, and reaching down even to the hem of the garment, which is invariably a double-breasted one, made upon the good old dining-out principle of leaving plenty of room in the victualling department. To complete the catalogue of raiment, the untalkaboutables have so little right to the name of drab, that it would cause a controversy on the point. Perhaps nothing in life can more exquisitely illustrate the Desdemona feeling of divided duty, than the portion of manufactured calf-skin appropriated to the peripatetic purposes of these gentry; they are, in point of fact, invariably that description of mud-markers known in the purlieus of Liecester-square, and at all denominations of “boots”—great, little, red, and yellow—as eight-and-sixpenny Bluchers. But the afore-mentioned drabs are strapped down with such pertinacity as to leave the observer in extreme doubt whether the Prussian hero of that name is their legitimate sponsor, or the glorious Wellington of our own sea-girt isle. Indeed, it has been rumoured that (as there never was a pair of either of the illustrious heroes) these gentlemen, for the sake of consistency, invariably perambulate in one of each. We scarcely know whether it be so or not—we merely relate what we have heard; but we incline to the two Bluchers, because of the eight-and-six. The only additional expense likely to add any emolument to the tanner’s interest (we mean no pun) is the immense extent of sixpenny straps generally worn. These are described by a friend of ours as belonging to the great class of coaxers; and their exertions in bringing (as a nautical man would say) the trowsers to bear at all, is worthy of notice. There is a legend extant (a veritable legend, which emanated from one of the fraternity who had been engaged three weeks at her Majesty’s theatre, as one of twenty in an unknown chorus, the chief peculiarity of the affair being the close approximation of some of his principal foreign words to “Tol de rol,” and “Fal the ral ra”), in which it was asserted, that from a violent quarrel with a person in the grass-bleached line, the body corporate determined to avoid any unnecessary use of that commodity. In the way of wristbands, the malice of the above void is beautifully nullified, inasmuch as the most prosperous linen-draper could never wish to have less linen on hand. As we are describing the genus in black and white, we may as well state at once, those are the colours generally casing the throats from whence their sweet sounds issue; these ties are garnished with union pins, whose strong mosaic tendency would, in the Catholic days of Spain (had they been residents), have consigned them to the lowest dungeons of the Inquisition, and favoured them with an exit from this breathing world, amid all the uncomfortable pomp of an auto-da-fe.

It is a fact on record, that no one of the body ever had a cold in his head; and this peculiarity, we presume, exempts them from carrying pocket-handkerchiefs, a superfluity we never witnessed in their hands, though they indulge in snuff-boxes which assume the miniture form of French plum-cases, richly embossed, with something round the edges about as much in proportion to the box as eighteen insides are to a small tax-cart. This testimonial is generally (as the engraved inscription purports) given by “several gentlemen” (who are, unfortunately, in these instances, always anonymous—which circumstance, as they are invariably described as “admirers of talent,” is much to be regretted, and, we trust, will soon be rectified). We believe, like the immortal Jack Falstaff, they were each born at four o’clock of the morning, with a bald head, and something of a round belly; certain it is, they are universally thin in the hair, and exhibit strong manifestation of obesity.

The further marks of identity consist in a ring very variously chased, and the infallible insignia of a tuning-fork: without this no professional singer does or can exist. The thing has been tried, and found a failure. Its uses are remarkable and various: like the “death’s-head and cross-bones” of the pirates, or the wand, globe, and beard of the conjuror, it is their sure and unvarying sign. We have in our mind’s eye one of the species even now—we see him coquetting with the fork, compressing it with gentle fondness, and then (that all senses may be called into requisition) resting it against his eye-tooth to catch the proper tone. Should this be the prelude to his own professional performance, we see it returned, with a look of profound wisdom, to the right-hand depository of the nondescript and imaginary velvet double-breaster—we follow his eyes, till, with peculiar fascination, they fix upon the far-off cornice of the most distant corner of the smoke-embued apartment—we perceive the extension of the dexter hand employed in innocent dalliance with the well-sucked peel of a quarter of an orange, whilst the left is employed with the links of what would be a watch-guard, if the professional singer had a watch. We hear the three distinct hems—oblivion for a moment seizes us—the glasses jingle—two auctioneers’ hammers astonish the mahogany—several dirty hands are brought in violent and noisy contact—we are near a friend of the vocalist—our glass of gin-and-water (literally warm without) empties itself over our lower extremities, instigated thereto by the gymnastic performances of the said zealous friend—and with an exclamation that, were Mawworn present, would cost us a shilling, we find the professional singer has concluded, and is half stooping to the applause, and half lifting his diligently-stirred grog, gulping down the “creature comfort” with infinite satisfaction.

—There goes the hammer again! (Rubins has a sinecure compared to that fat man). “A glee, gents!—a glee!”—Ah! there they are—three coats—three collars—Heaven knows how many buttons!—three bald heads, three stout stomachs, three mouths, stuffed with three tuning-forks, nodding and conferring with a degree of mystery worthy of three Guy Faux.”—What is the subject?

“Hail smilig born.”

That’s a good guess! By the way, the vulgar notion of singing ensemble is totally exploded by these gentry—each professional singer, as a professional singer, sings his very loudest, in justice to himself; if his brethren want physical power, that’s no fault of his, he don’t. Professional singers indulge in small portions of classic lore: among the necessary acquirements is, “Non nobis,” &c. &c.; that is, they consider they ought to know the airs. The words are generally delivered as follows:—Don—dobis—do—by—de. A clear enunciation is not much cultivated among the clever in this line.

In addition to the few particulars above, it may be as well to mention, they treat all tavern-waiters with great respect, which is more Christian-like, as the said waiters never return the same—sit anywhere, just to accommodate—eat everything, to prove they have no squeamish partialities—know to a toothful what a bottom of brandy should be—the exact quantity they may drink, free gratis, and the most likely victim to drop upon for any further nourishment they may require. Their acquirements in the musical world are rendered clear, by the important information that “Harry Phillips knows what he’s about”—“Weber was up to a thing or two.” A baritone ain’t the sort of thing for tenor music: and when they sung with some man (nobody ever heard of), they showed him the difference, and wouldn’t mind—“A cigar?” “Thank you, sir!—seldom smoke—put it in my pocket—(aside) that makes a dozen! Your good health, sir!—don’t dislike cold, though I generally take it warm—didn’t mean that as a hint, but, since you have ordered it, I’ll give you a toast—Here’s—THE PROFESSIONAL SINGER!”

FUSBOS.

Bards of old have sung the vine

Such a theme shall ne’er be mine;

Weaker strains to me belong,

Pæans sung to thee, Souchong!

What though I may never sip

Rubies from my tea-cup’s lip;

Do not milky pearls combine

In this steaming cup of mine?

What though round my youthful brow

I ne’er twine the myrtle’s bough?

For such wreaths my soul ne’er grieves.

Whilst I own my Twankay’s leaves.

Though for me no altar burns,

Kettles boil and bubble—urns

In each fane, where I adore—

What should mortal ask for more!

I for Pidding, Bacchus fly,

Howqua shall my cup supply;

I’ll ne’er ask for amphoræ,

Whilst my tea-pot yields me tea.

Then, perchance, above my grave,

Blooming Hyson sprigs may wave;

And some stately sugar-cane,

There may spring to life again:

Bright-eyed maidens then may meet,

To quaff the herb and suck the sweet.

DEAR SIR,—I was a-sitting the other evening at the door of my kennel, thinking of the dog-days and smoking my pipe (blessings on you, master, for teaching me that art!), when one of your prospectuses was put into my paw by a spaniel that lives as pet-dog in a nobleman’s family. Lawk, sir! what misfortunes can have befallen you, that you are obleeged to turn author?

I remember the poor devil as used to supply us with dialect—what a face he had! It was like a mouth-organ turned edgeways; and he looked as hollow as the big drum, but warn’t half so round and noisy. You can’t have dwindled down to that, surely! I couldn’t bear to see your hump and pars pendula (that’s dog Latin) shrunk up like dried almonds, and titivated out in msty-fusty toggery—I’m sure I couldn’t! The very thought of it is like a pound weight at the end of my tail.

I whined like any thing, calling to my missus—for you must know that I’ve married as handsome a Scotch terrier as you ever see. “Vixen,” says I, “here’s the poor old governor up at last—I knew that Police Act would drive him to something desperate.”

“Why he hasn’t hung himself in earnest, and summoned you on his inquest!” exclaimed Mrs. T.

“Worse nor that,” says I; “he’s turned author, and in course is stewed up in some wery elevated apartment during this blessed season of the year, when all nature is wagging with delight, and the fairs is on, and the police don’t want nothing to do to warm ‘em, and consequentially sees no harm in a muster of infantry in bye-streets. It’s very hawful.”

Vixen sighed and scratched her ear with her right leg, so I know’d she’d something in her head, for she always does that when anything tickles her. “Toby,” says she, “go and see the old gentleman; perhaps it might comfort him to larrup you a little.”

“Very well,” says I, “I’ll be off at once; so put me by a bone or two for supper, should any come out while I’m gone; and if you can get the puppies to sleep before I return, I shall be so much obleeged to you.” Saying which, I toddled off for Wellington-street. I had just got to the coach-stand at Hyde Park Corner, when who should I see labelled as a waterman but the one-eyed chap we once had as a orchestra—he as could only play “Jim Crow” and the “Soldier Tired.” Thinks I, I may as well pass the compliment of the day with him; so I creeps under the hackney-coach he was standing alongside on, intending to surprise him; but just as I was about to pop out he ran off the stand to un-nosebag a cab-horse. Whilst I was waiting for him to come back, I hears the off-side horse in the wehicle make the following remark:—

OFF-SIDE HORSE—(twisting his tail about like anything)—Curse the flies!

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—You may say that. I’ve had one fellow tickling me this half-hour.

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—Ours is a horrid profession! Phew! the sun actually penetrates my vertebra.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Werterbee! What’s that?

OFF-SIDE HORSE—(impatiently).—The spine, my friend (whish! whish!)

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Ah! it is a shameful thing to dock us as they does. If the marrow in one’s backbone should melt, it would be sartin to run out at the tip of one’s tail. I say, how’s your feed?

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—Very indifferent—the chaff predominates—(munch) not bene by any means.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Beany! Lord bless your ignorance! I should be satisfied if they’d only make it oaty now and then. How long have you been in the hackney line?

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—I have occupied my present degraded position about two years. Little thought my poor mama, when I was foaled, that I should ever come to this.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Ah! it ain’t very respectable, is it?—especially since the cabs and busses have druv over our heads. What was you put to?—you look as if you had been well brought up.

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—My mama was own sister to Lottery, but unfortunately married a horse much below her in pedigree. I was the produce of that union. At five years old I entered the army under Ensign Dashard.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE—Bless me, how odd! I was bought at Horncastle, to serve in the dragoons; but the wetternary man found out I’d a splint, and wouldn’t have me! I say, ain’t that stout woman with a fat family looking at us?

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—I’m afraid she is. People of her grade in society are always partial to a dilatory shillingworth.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE—Ay, and always lives up Snow-hill, or Ludgate-hill, or Mutton-hill, or a hill somewhere.

WOMAN.—Coach!

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—She’s ahailing us! I wonder whether she’s narvous? I’ll let out with my hind leg a bit—(kick)—O Lord! the rheumatiz!

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—Pray don’t. I abjure subterfuges; they are unworthy of a thoroughbred.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Thoroughbred? I like that! Haven’t you just acknowledged that you were a cocktail? Thank God! she’s moving on. Hallo! there’s old Readypenny!—a willanous Tory.

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—I beg to remark that my principles are Conservative.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—And I beg to remark that mine isn’t. I sarved Readypenny out at Westminster ‘lection the other day. He got into our coach to go to the poll, and I wouldn’t draw an inch. I warn’t agoing to take up a plumper for Rous.

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—I declare the obese female returns.

WOMAN.—Coach! Hallo! Coach!

WATERMAN.—Here you is, ma’am. Kuck! kuck! kuck!—Come along!—(Pulling the coach and horses).

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—O heavens! I am too stiff to move, and this brute will pull my head off.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Keep it on one side, and you spiles his purchase.

WATERMAN—Come up, you old brute!

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—Old brute! What evidence of a low mind!—[The stout woman and fat family ascend the steps of the coach].

COACH.—O law! oh, law! Week! week! O law!—O law! Week! week!

NEAR-SIDE HORSE—Do you hear how the poor old thing’s a sufferin’?—She must feel it a good deal to have her squabs sat on by everybody as can pay for her. She was built by Pearce, of Long-acre, for the Duchess of Dorsetshire. I wonder her perch don’t break—she has been crazy a long time.

WATERMAN.—Snow-hill—opposite the Saracen’s Head.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—I know’d it!

COACHMAN.—Kuck! kuck!

WHIP.—Whack! whack!

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—Pull away, my dear fellow; a little extra exertion may save us from flagellation.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Well, I’m pulling, ain’t I?

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—I don’t like to dispute your word; but—(whack)—Oh! that was an abrasion on my shoulder.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—A raw you mean. Who’s not pulling now, I should like to know!

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—I couldn’t help hopping then; you know what a grease I have in my hind leg.

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Well, haven’t I a splint and a corn, and ain’t one of my fore fetlocks got a formoses, and my hind legs the stringhalt?

WOMAN.—Stop! stop!

COACHMAN.—Whoo up!—d—n you!

OFF-SIDE HORSE.—There goes my last masticator!

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—And I’m blow’d if he hasn’t jerked my head so that he’s given me a crick in the neck; but never mind; if she does get out here, we shall save the hill.

WOMAN.—Three doors higher up.

COACHMAN.—Chuck! chuck!

WHIP.—Whack! whack!

COACHMAN.—Come up, you varmint!

OFF-SIDE HORSE—Varmint! and to me! the nephew of the great Lottery! O Pegasus! what shall I come to next!

NEAR-SIDE HORSE.—Alamode beef, may be, or perhaps pork sassages!

The old woman was so long in that house where she stopped, that I was obleeged to toddle home, for my wife has a rather unpleasant way of taking me by the scruff of my neck if I ain’t pretty regular in my hours.

Yours, werry obediently, TOBY.

Communicated exclusively to this Journal by MASTER JONES, whose services we have succeeded in retaining, though opposed by the enlightened manager of a metropolitan theatre, whose anxiety to advance the interest of the drama is only equalled by his ignorance of the means.

Since the dissolution of Parliament, Lord Melbourne has confined himself entirely to stews.

Stalls have been fitted up in the Royal nursery for the reception of two Alderney cows, preparatory to the weaning of the infant Princess; which delicate duty Mrs. Lilly commences on Monday next.

Sir Robert Peel has been seen several times this week in close consultation with the chief cook. Has he been offered the premiership?

Mr. Moreton Dyer, “the amateur turner,” has been a frequent visitor at the palace of late. Palmerston, it is whispered, has been receiving lessons in the art. We are surprised to hear this, for we always considered his lordship a Talleyrand in turning.

By winter’s chill the fragrant flower is nipp’d,

To be new-clothed with brighter tints in spring;

The blasted tree of verdant leaves is stripp’d,

A fresher foliage on each branch to bring;

The aërial songster moults his plumerie,

To vie in sleekness with each feather’d brother:

A twelvemonth’s wear hath ta’en thy nap from thee,

My seedy coat!—When shall I get another?

NOTE.—Confiding tailors are entreated to send their addresses, pre-paid, to PUNCH’S office.

P.S.—None need apply who refuse three years’ acceptances. If the bills be made renewable, by agreement, “continuations” will be taken in any quantity.—FITZROY FIPS.

(Enter PUNCH.)

PUNCH.—R-r-r-roo-to-tooit-tooit?

(Sings.)

“Wheel about and turn about,

And do jes so;

Ebery time I turn about,

I jump Jim Crow.”

MANAGER.—Hollo, Mr. Punch! your voice is rather husky to-day.

PUNCH.—Yes, yes; I’ve been making myself as hoarse as a hog, bawling to the free and independent electors of Grogswill all the morning. They have done me the honour to elect me as their representative in Parliament. I’m an M.P. now.

MANAGER.—An M.P.! Gammon, Mr. Punch.

THE DOG TOBY.—Bow, wow, wow, wough, wough!

PUNCH.—Fact, upon my honour. I’m at this moment an unit in the collective stupidity of the nation.

DOG TOBY.—R-r-r-r-r-r—wough—wough!

PUNCH.—Kick that dog, somebody. Hang the cur, did he never see a legislator before, that he barks at me so?

MANAGER.—A legislator, Mr. Punch? with that wooden head of yours! Ho! ho! ho! ho!

PUNCH.—My dear sir, I can assure you that wood is the material generally used in the manufacture of political puppets. There will be more blockheads than mine in St. Stephen’s, I can tell you. And as for oratory, why I flatter my whiskers I’ll astonish them in that line.

MANAGER.—But on what principles did you get into Parliament, Mr. Punch?

PUNCH.—I’d have you know, sir, I’m above having any principles but those that put money in my pocket.

MANAGER.—I mean on what interest did you start?

PUNCH.—On self-interest, sir. The only great, patriotic, and noble feeling that a public man can entertain.

MANAGER.—Pardon me, Mr. Punch; I wish to know whether you have come in as a Whig or a Tory?

PUNCH.—As a Tory, decidedly, sir. I despise the base, rascally, paltry, beggarly, contemptible Whigs. I detest their policy, and—

THE DOG TOBY.—Bow, wow, wough, wough!

MANAGER.—Hollo! Mr. Punch, what are you saying? I understood you were always a staunch Whig, and a supporter of the present Government.

PUNCH.—So I was, sir. I supported the Whigs as long as they supported themselves; but now that the old house is coming down about their ears, I turn my back on them in virtuous indignation, and take my seat in the opposition ‘bus.

MANAGER.—-But where is your patriotism, Mr. Punch?

PUNCH.—Where every politician’s is, sir—in my breeches’ pocket.

MANAGER.—And your consistency, Mr. Punch?

PUNCH.—What a green chap you are, after all. A public man’s consistency! It’s only a popular delusion, sir. I’ll tell you what’s consistency, sir. When one gentleman’s in and won’t come out, and when another gentleman’s out and can’t get in, and when both gentlemen persevere in their determination—that’s consistency.

MANAGER.—I understand; but still I think it is the duty of every public man to——

PUNCH.—(sings)—

“Wheel about and turn about, And do jes so; Ebery time he turn about, He jumps Jim Crow.”

MANAGER.—Then it is your opinion that the prospects of the Whigs are not very flattering?

PUNCH.—’Tis all up with them, as the young lady remarked when Mr. Green and his friends left Wauxhall in the balloon; they haven’t a chance. The election returns are against them everywhere. England deserts them—Ireland fails them—Scotland alone sticks with national attachment to their backs, like a—

THE DOG TOBY.—Bow, wow, wow, wough!

MANAGER.—Of course, then, the Tories will take office—?

PUNCH.—I rayther suspect they will. Have they not been licking their chops for ten years outside the Treasury door, while the sneaking Whigs were helping themselves to all the fat tit-bits within? Have they not growled and snarled all the while, and proved by their barking that they were the fittest guardians of the country? Have they not wept over the decay of our ancient and venerable constitution—? And have they not promised and vowed, the moment they got into office, that they would—Send round the hat.

MANAGER.—Very good, Mr. Punch; but I should like to know what the Tories mean to do about the corn-laws? Will they give the people cheap food?

PUNCH.—No, but they’ll give them cheap drink. They’ll throw open the Thames for the use of the temperance societies.

MANAGER.—But if we don’t have cheap corn, our trade must be destroyed, our factories will be closed, and our mills left idle.

PUNCH.—There you’re wrong. Our tread-mills will be in constant work; and, though our factories should be empty, our prisons will be quite full.

MANAGER.—That’s all very well, Mr. Punch; but the people will grumble a leetle if you starve them.

PUNCH.—Ay, hang them, so they will; the populace have no idea of being grateful for benefits. Talk of starvation! Pooh!—I’ve studied political economy in a workhouse, and I know what it means. They’ve got a fine plan in those workhouses for feeding the poor devils. They do it on the homoeopathic system, by administering to them oatmeal porridge in infinitessimal doses; but some of the paupers have such proud stomachs that they object to the diet, and actually die through spite and villany. Oh! ’tis a dreadful world for ingratitude! But never mind—Send round the hat.

MANAGER.—What is the meaning of the sliding scale, Mr. Punch?

PUNCH.—It means—when a man has got nothing for breakfast, he may slide his breakfast into his lunch; then, if he has got nothing for lunch, he may slide that into his dinner; and if he labours under the same difficulties with respect to the dinner, he may slide all three meals into his supper.

MANAGER.—But if the man has got no supper?

PUNCH.—Then let him wish he may get it.

MANAGER.—Oh! that’s your sliding scale?

PUNCH.—Yes; and a very ingenious invention it is for the suppression of victuals. R-r-r-roo-to-tooit-tooit! Send round the hat.

MANAGER.—At this rate, Mr. Punch, I suppose you would not be favourable to free trade?

PUNCH.—Certainly not, sir. Free trade is one of your new-fangled notions that mean nothing but free plunder. I’ll illustrate my position. I’m a boy in a school, with a bag of apples, which, being the only apples on my form, I naturally sell at a penny a-piece, and so look forward to pulling in a considerable quantity of browns, when a boy from another form, with a bigger bag of apples, comes and sells his at three for a penny, which, of course, knocks up my trade.

MANAGER.—But it benefits the community, Mr. Punch.

PUNCH.—D—n the community! I know of no community but PUNCH and Co. I’m for centralization—and individualization—every man for himself, and PUNCH for us all! Only let me catch any rascal bringing his apples to my form, and see how I’ll cobb him. So now—send round the hat—and three cheers for

O Reveal, thou fay-like stranger,

Why this lonely path you seek;

Every step is fraught with danger

Unto one so fair and meek.

Where are they that should protect thee

In this darkling hour of doubt?

Love could never thus neglect thee!—

Does your mother know you’re out?

Why so pensive, Peri-maiden?

Pearly tears bedim thine eyes!

Sure thine heart is overladen,

When each breath is fraught with sighs.

Say, hath care life’s heaven clouded,

Which hope’s stars were wont to spangle?

What hath all thy gladness shrouded?—

Has your mother sold her mangle?

We are requested to state, by the Marquis of W——, that, for the convenience of the public, he has put down one of his carriages, and given orders to Pearce, of Long-acre, for the construction of an easy and elegant stretcher.

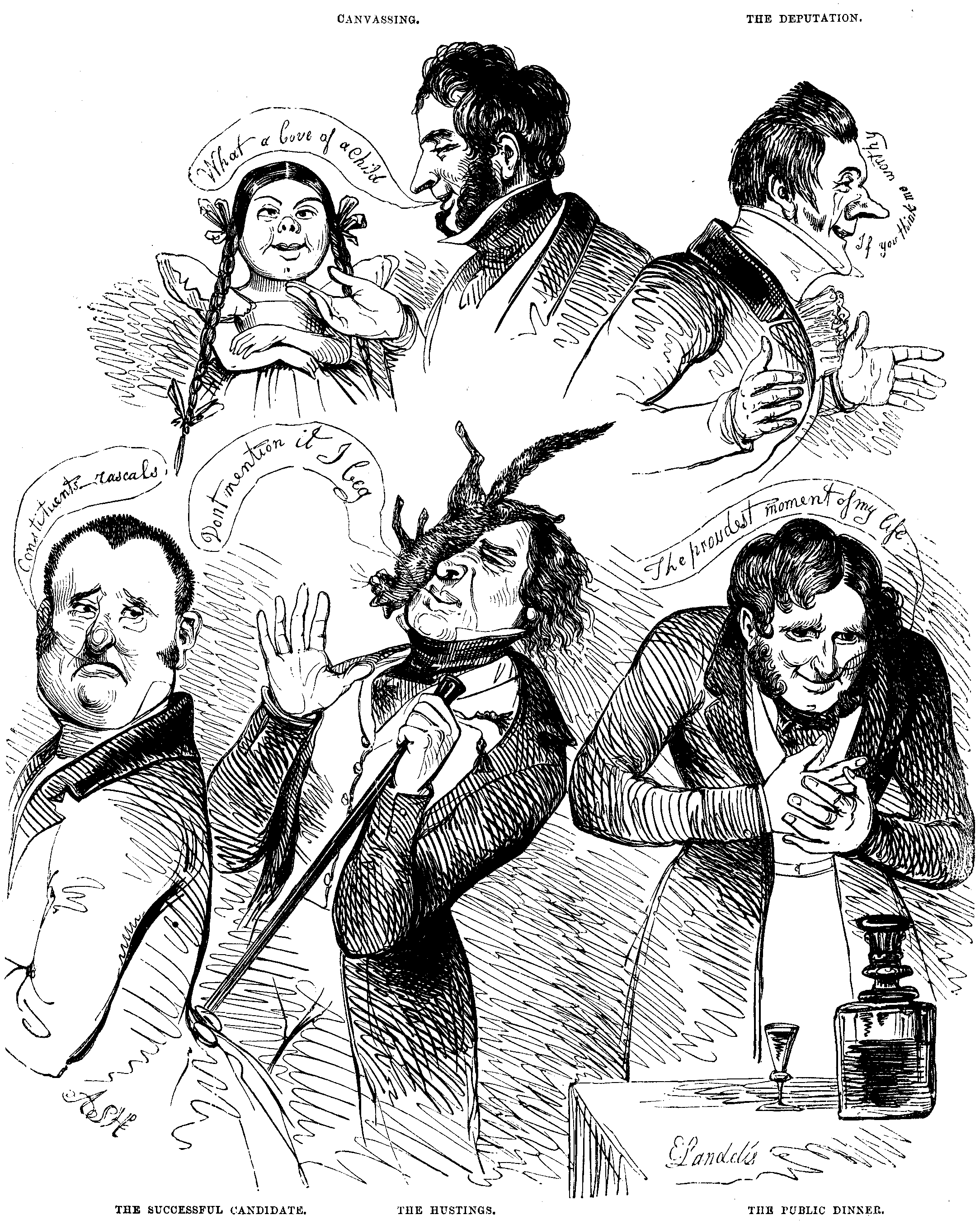

CANVASSING. What a love of a child

THE DEPUTATION. If you think me worthy

THE SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE. Constituents--rascals

THE HUSTINGS. Don't mention it I beg

THE PUBLIC DINNER. The proudest moment of my life

PUNCH begs most solemnly to assure his friends and the artists in general, that should the violent cold with which he has been from time immemorial afflicted, and which, although it has caused his voice to appear like an infant Lablache screaming through horse-hair and thistles, yet has not very materially affected him otherwise—should it not deprive him of existence—please Gog and Magog, he will, next season, visit every exhibition of modern art as soon as the pictures are hung; and further, that he will most unequivocally be down with his coup de baton upon every unfortunate nob requiring his peculiar attention.

That he independently rejects the principles upon which these matters are generally conducted, he trusts this will be taken as an assurance: should the handsomest likeness-taker gratuitously offer to paint PUNCH’S portrait in any of the most favourite and fashionable styles, from the purest production of the general mourning school—and all performed by scissars—to the exquisitely gay works of the President of the Royal Academy, even though his Presidentship offer to do the nose with real carmine, and throw Judy and the little one into the back-ground, PUNCH would not give him a single eulogistic syllable unmerited. A word to the landscape and other perpetrators: none of your little bits for PUNCH—none of your insinuating cabinet gems—no Art-ful Union system of doing things—Hopkins to praise for one reason, Popkins to censure for another—and as PUNCH has been poking his nose into numberless unseen corners, and, notwithstanding its indisputable dimensions, has managed to screen it from observation, he has thereby smelt out several pretty little affairs, which shall in due time be exhibited and explained in front of his proscenium, for special amusement. In the mean time, to prove that PUNCH is tolerably well up in this line of pseudo-criticism, he has prepared the following description of the private view of either the Royal Academy or the Suffolk-street Gallery, or the British Institution, for 1842, for the lovers of this very light style of reading; and to make it as truly applicable to the various specimens of art forming the collection or collections alluded to, he has done it after the peculiar manner practised by the talented conductor of a journal purporting to be exclusively set apart to that effort. To illustrate with what strict attention to the nature of the subject chosen, and what an intimate knowledge of technicalities the writer above alluded to displays, and with what consummate skill he blends those peculiarities, the reader will have the kindness to attach the criticism to either of the works (hereunder catalogued) most agreeably to his fancy. It will be, moreover, shown that this is a thoroughly impartial way of performing the operation of soft anointment.

THE UNERRING FOR PORTRAITS ONLY: |

|

| Portrait of the miscreant who attempted to assassinate Mr. Macreath. | The head is extremely well painted, and the light and shade distributed with the artist's usual judgement. |

| VALENTINE VERMILION. | |

| Portrait of His Majesty the King of Hanover. | |

| BY THE SAME. | |

| Portrait of the boy who got into Buckingham Palace. | |

| GEOFFERY GLAZEM. | OR THUS: |

| Portrait of Lord John Russell. | An admirable likeness of the original, and executed with that breadth and clearness so apparent in this clever painter's works. |

| BY THE SAME. | |

| Portrait of W. Grumbletone, Esq., in the character of Joseph Surface. | |

| PETER PALETTE. | |

| Portrait of Sir Robert Peel | |

| BY THE SAME. | OR THUS: |

| Portrait of the Empress of Russia. | A well-drawn and brilliantly painted portrait, calculated to sustain the fame already gained by this our favourite painter. |

| VANDYKE BROWN. | |

| Portrait of the infant Princess. | |

| BY THE SAME. | |

| Portrait of Mary Mumblegums, aged 170 years. | |

| BY THE SAME. | |

THE UNERRING FOR EVERY SUBJECT: |

|

| The Death of Abel. | This picture is well arranged and coloured with much truth to nature; the chiaro-scuro is admirably managed. |

| MICHAEL McGUELP. | |

| Dead Game. | |

| THOMAS TICKLEPENCIL. | |

| Vesuvius in Eruption. | |

| CHARLES CARMINE, R.A. | |

| Portraits of Mrs. Punch and Child. | |

| R.W. BUSS. | |

| Cattle returning from the Watering Place. | |

| R. BOLLOCK. | OR THUS: |

| "We won't go home till Morning." | |

| M. WATERFORD, R.H.S. | This is one of the cleverest productions in the Exhibition; there is a transparency in the shadows equal to Rembrandt. |

| The infant Cupid sleeping. | |

| R. DADD. | |

| Portrait of Lord Palmerston. | |

| A.L.L. UPTON. | |

| Coast Scene: Smugglers on the look out. | |

| H. PARKER. | |

| Portrait of Captain Rous, M.P. | |

| J. WOOD. | |

Should the friends of any of the artists deem the praise a little too oily, they can easily add such a tag as the following:—“In our humble judgment, a little more delicacy of handling would not be altogether out of place;” or, “Beautiful as the work under notice decidedly is, we recollect to have received perhaps as much gratification in viewing previous productions by the same.”

This artist is, we much fear, on the decline; we no longer see the vigour of handling and smartness of conception formerly apparent in his works: or, “A little stricter attention to drawing, as well as composition, would render this artist’s works more recommendatory.”

Either of the following, taken conjointly or separately: “A perfect daub, possessing not one single quality necessary to create even the slightest interest—a disgrace to the Exhibition—who allowed such a wretched production to disgrace these walls?—woefully out of drawing, and as badly coloured,” and such like.

Well, lawks-a-day! things seem going on uncommon queer,

For they say that the Tories are bowling out the Whigs almost everywhere;

And the blazing red of my beadle’s coat is turning to pink through fear,

Lest I should find myself and staff out of Office some time about the end of the year.

I’ve done nothing so long but stand under the magnificent portico

Of Somerset House, that I don’t know what I should do if I was for to go!

What the electors are at, I can’t make out, upon my soul,

For it’s a law of natur’ that the whig should be atop of the poll.

I’ve had a snug berth of it here for some time, and don’t want to cut the connexion;

But they do say the Whigs must go out, because they’ve NO OTHER ELECTION;

What they mean by that, I don’t know, for ain’t they been electioneering—

That is, they’ve been canvassing, and spouting, and pledging, and ginning, and beering.

Hasn’t Crawford and Pattison, Lyall, Masterman, Wood, and Lord John Russell,

For ever so long been keeping the Great Metropolis in one alarming bussel?

Ain’t the two first retired into private life—(that’s the genteel for being rejected)?

And what’s more, the last four, strange to say, have all been elected.

Then Finsbury Tom and Mr. Wakley, as wears his hair all over his coat collar,

Hav’n’t they frightened Mr. Tooke, who once said he could beat them Hollar?

Then at Lambeth, ain’t Mr. Baldwin and Mr. Cabbell been both on ‘em bottled

By Mr. D’Eyncourt and Mr. Hawes, who makes soap yellow and mottled!

And hasn’t Sir Benjamin Hall, and the gallant Commodore Napier,

Made such a cabal with Cabbell and Hamilton as would make any chap queer?

Whilst Sankey, who was backed by a Cleave-r for Marrowbone looks cranky,

Acos the electors, like lisping babbies, cried out “No Sankee?”

Then South’ark has sent Alderman Humphrey and Mr. B. Wood,

Who has promised, that if ever a member of parliament did his duty—he would!

Then for the Tower Hamlets, Robinson, Hutchinson, and Thompson, find that they’re in the wrong box,

For the electors, though turned to Clay, still gallantly followed the Fox;

Whilst Westminster’s chosen Rous—not Rouse of the Eagle—tho’ I once seed a

Picture where there was a great big bird, very like a goose, along with a Leda.

And hasn’t Sir Robert Peel and Mr. A’Court been down to Tamworth to be reseated?

They ought to get an act of parliament to save them such fatigue, for its always—ditto repeated.

Whilst at Leeds, Beckett and Aldam have put Lord Jocelyn into a considerable fume,

Who finds it no go, though he’s added up the poll-books several times with the calculating boy, Joe Hume.

So if there’s been no other election, I should like to find out

What all the late squibbing and fibbing, placarding, and blackguarding, losing and winning, beering and ginning, and every other et cetera, has been about!

Black bottles at Brighton,

To darken your fame;

Black Sundays at Hounslow,

To add to your shame.

Black balls at the club,

Show Lord Hill’s growing duller:

He should change your command

To the guards of that colour.

English—it has been remarked a thousand and odd times—is one of the few languages which is unaccompanied with gesticulation. Your veritable Englishman, in his discourse, is as chary as your genuine Frenchman is prodigal, of action. The one speaks like an oracle, the other like a telegraph.

Mr. Brown narrates the death of a poor widower from starvation, with his hands fast locked in his breeches’ pocket, and his features as calm as a horse-pond. M. le Brun tells of the debut of the new danseuse, with several kisses on the tips of his fingers, a variety of taps on the left side of his satin waistcoat, and his head engulfed between his two shoulders, like a cock-boat in a trough of the sea.