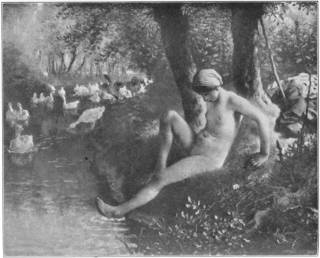

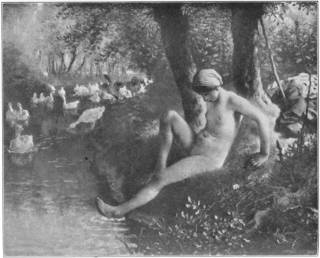

From a photograph by Braun, Clement & Co. Plate 1.—Millet. "The Goose Girl." In the collection of Mme. Saulnier, Bordeaux.

From a photograph by Braun, Clement & Co. Plate 1.—Millet. "The Goose Girl." In the collection of Mme. Saulnier, Bordeaux.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Artist and Public, by Kenyon Cox

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Artist and Public

And Other Essays On Art Subjects

Author: Kenyon Cox

Release Date: September 5, 2005 [EBook #16655]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ARTIST AND PUBLIC ***

Produced by Ted Garvin, Melissa Er-Raqabi and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

From a photograph by Braun, Clement & Co. Plate 1.—Millet. "The Goose Girl." In the collection of Mme. Saulnier, Bordeaux.

From a photograph by Braun, Clement & Co. Plate 1.—Millet. "The Goose Girl." In the collection of Mme. Saulnier, Bordeaux.

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

NEW YORK MCMXIV

Copyright, 1914, by Charles Scribner's Sons

Published September, 1914

TO

J.D.C.

IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF UNFAILING KINDNESS

THIS BOOK IS INSCRIBED

In "The Classic Point of View," published three years ago, I endeavored to give a clear and definitive statement of the principles on which all my criticism of art is based. The papers here gathered together, whether earlier or later than that volume, may be considered as the more detailed application of those principles to particular artists, to whole schools and epochs, even, in one case, to the entire history of the arts. The essay on Raphael, for instance, is little else than an illustration of the chapter on "Design"; that on Millet illustrates the three chapters on "The Subject in Art," on "Design," and on "Drawing"; while "Two Ways of Painting" contrasts, in specific instances, the classic with the modern point of view.

But there is another thread connecting these essays, for all of them will be found to have some bearing, more or less direct, upon the subject of the title essay. "The Illusion of Progress" elaborates a point more slightly touched upon in "Artist and Public"; the careers of Raphael and Millet are capital instances of the happy productiveness of an artist in sympathy with his public or of the difficulties, nobly conquered in this case, of an artist without public appreciation; the greatest merit attributed to "The American School" is an abstention from the extravagances of those who would make incomprehensibility a test of greatness. Finally, the work of Saint-Gaudens is a noble example of art fulfilling its social function in expressing and in elevating the ideals of its time and country.

This last essay stands, in some respects, upon a different footing from the others. It deals with the work and the character of a man I knew and loved, it was originally written almost immediately after his death, and it is therefore colored, to some extent, by personal emotion. I have revised it, rearranged it, and added to it, and I trust that this coloring may be found to warm, without falsifying, the picture.

The essay on "The Illusion of Progress" was first printed in "The Century," that on Saint-Gaudens in "The Atlantic Monthly." The others originally appeared in "Scribner's Magazine."

KENYON COX.

Calder House,

Croton-on-Hudson,

June 6, 1914.

| essay | page | |

| I. | Artist and Public | 1 |

| II. | Jean François Millet | 44 |

| III. | The Illusion of Progress | 77 |

| IV. | Raphael | 99 |

| V. | Two Ways of Painting | 134 |

| VI. | The American School | 149 |

| VII. | Augustus Saint-Gaudens | 169 |

| Millet: | ||

| 1. | "The Goose Girl," Saulnier Collection, Bordeaux | Frontispiece |

| facing page | ||

| 2. | "The Sower," Vanderbilt Collection, Metropolitan Museum, New York | 46 |

| 3. | "The Gleaners," The Louvre | 50 |

| 4. | "The Spaders" | 54 |

| 5. | "The Potato Planter," Shaw Collection | 58 |

| 6. | "The Grafter," William Rockefeller Collection | 62 |

| 7. | "The New-Born Calf," Art Institute, Chicago | 66 |

| 8. | "The First Steps," | 70 |

| 9. | "The Shepherdess," Chauchard Collection, Louvre | 72 |

| 10. | "Spring," The Louvre | 74 |

| Raphael: | ||

| 11. | "Poetry," The Vatican | 112 |

| 12. | "The Judgment of Solomon," The Vatican | 114 |

| 13. | The "Disputa," The Vatican | 116 |

| 14. | "The School of Athens," The Vatican | 118 |

| 15. | "Parnassus," The Vatican | 120 |

| 16. | "Jurisprudence," The Vatican | 122 |

| 17. | "The Mass of Bolsena," The Vatican | 124 |

| 18. | "The Deliverance of Peter," The Vatican | 126 |

| 19. | "The Sibyls," Santa Maria della Pace, Rome | 128 |

| 20. | "Portrait of Tommaso Inghirami," Gardner Collection | 130 |

| John S. Sargent: | ||

| 21. | "The Hermit," Metropolitan Museum, New York | 136 |

| Titian: | ||

| 22. | "Saint Jerome in the Desert," Brera Gallery, Milan | 142 |

| Saint-Gaudens: | ||

| 23. | "Plaquette Commemorating Cornish Masque" | 182 |

| 24. | "Amor Caritas" | 196 |

| 25. | "The Butler Children" | 206 |

| 26. | "Sarah Redwood Lee" | 208 |

| 27. | "Farragut," Madison Square, New York | 212 |

| 28. | "Lincoln," Chicago, Ill. | 214 |

| 29. | "Deacon Chapin," Springfield, Mass. | 216 |

| 30. | "Adams Memorial," Washington, D.C. | 218 |

| 31. | "Shaw Memorial," Boston, Mass. | 220 |

| 32. | "Sherman," The Plaza, Central Park, New York | 224 |

In the history of art, as in the history of politics and in the history of economics, our modern epoch is marked off from all preceding epochs by one great event, the French Revolution. Fragonard, who survived that Revolution to lose himself in a new and strange world, is the last at the old masters; David, some sixteen years his junior, is the first of the moderns. Now if we look for the most fundamental distinction between our modern art and the art of past times, I believe we shall find it to be this: the art of the past was produced for a public that wanted it and understood it, by artists who understood and sympathized with their public; the art of our time has been, for the most part, produced for a public that did not want it and misunderstood it, by artists who disliked and despised the public for which they worked. When artist and public were united, art was homogeneous and continuous. Since the divorce of artist and public art has been chaotic and convulsive.

That this divorce between the artist and his public—this dislocation of the right and natural relations between them—has taken place is certain. The causes of it are many and deep-lying in our modern civilization, and I can point out only a few of the more obvious ones.

The first of these is the emergence of a new public. The art of past ages had been distinctively an aristocratic art, created for kings and princes, for the free citizens of slave-holding republics, for the spiritual and intellectual aristocracy of the church, or for a luxurious and frivolous nobility. As the aim of the Revolution was the destruction of aristocratic privilege, it is not surprising that a revolutionary like David should have felt it necessary to destroy the traditions of an art created for the aristocracy. In his own art of painting he succeeded so thoroughly that the painters of the next generation found themselves with no traditions at all. They had not only to work for a public of enriched bourgeois or proletarians who had never cared for art, but they had to create over again the art with which they endeavored to interest this public. How could they succeed? The rift between artist and public had begun, and it has been widening ever since.

If the people had had little to do with the major arts of painting and sculpture, there had yet been, all through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a truly popular art—an art of furniture making, of wood-carving, of forging, of pottery. Every craftsman was an artist in his degree, and every artist was but a craftsman of a superior sort. Our machine-making, industrial civilization, intent upon material progress and the satisfaction of material wants, has destroyed this popular art; and at the same time that the artist lost his patronage from above he lost his support from below. He has become a superior person, a sort of demi-gentleman, but he has no longer a splendid nobility to employ him or a world of artist artisans to surround him and understand him.

And to the modern artist, so isolated, with no tradition behind him, no direction from above and no support from below, the art of all times and all countries has become familiar through modern means of communication and modern processes of reproduction. Having no compelling reason for doing one thing rather than another, or for choosing one or another way of doing things, he is shown a thousand things that he may do and a thousand ways of doing them. Not clearly knowing his own mind he hears the clash and reverberation of a thousand other minds, and having no certainties he must listen to countless theories.

Mr. Vedder has spoken of a certain "home-made" character which he considers the greatest defect of his art, the character of an art belonging to no distinctive school and having no definite relation to the time and country in which it is produced. But it is not Mr. Vedder's art alone that is home-made. It is precisely the characteristic note of our modern art that all of it that is good for anything is home-made or self-made. Each artist has had to create his art as best he could out of his own temperament and his own experience—has sat in his corner like a spider, spinning his web from his own bowels. If the art so created was essentially fine and noble the public has at last found it out, but only after years of neglect have embittered the existence and partially crippled the powers of its creator. And so, to our modern imagination, the neglected and misunderstood genius has become the very type of the great artist, and we have allowed our belief in him to color and distort our vision of the history of art. We have come to look upon the great artists of all times as an unhappy race struggling against the inappreciation of a stupid public, starving in garrets and waiting long for tardy recognition.

The very reverse of this is true. With the exception of Rembrandt, who himself lived in a time of political revolution and of the emergence to power of a burgher class, you will scarce find an unappreciated genius in the whole history of art until the beginning of the nineteenth century. The great masters of the Renaissance, from Giotto to Veronese, were men of their time, sharing and interpreting the ideals of those around them, and were recognized and patronized as such. Rembrandt's greatest contemporary, Rubens, was painter in ordinary to half the courts of Europe, and Velazquez was the friend and companion of his king. Watteau and Boucher and Fragonard painted for the frivolous nobility of the eighteenth century just what that nobility wanted, and even the precursors of the Revolution, sober and honest Chardin, Greuze the sentimental, had no difficulty in making themselves understood, until the revolutionist David became dictator to the art of Europe and swept them into the rubbish heap with the rest.

It is not until the beginning of what is known as the Romantic movement, under the Restoration, that the misunderstood painter of genius definitely appears. Millet, Corot, Rousseau were trying, with magnificent powers and perfect single-mindedness, to restore the art of painting which the Revolution had destroyed. They were men of the utmost nobility and simplicity of character, as far as possible from the gloomy, fantastic, vain, and egotistical person that we have come to accept as the type of unappreciated genius; they were classically minded and conservative, worshippers of the great art of the past; but they were without a public and they suffered bitter discouragement and long neglect. Upon their experience is founded that legend of the unpopularity of all great artists which has grown to astonishing proportions. Accepting this legend, and believing that all great artists are misunderstood, the artist has come to cherish a scorn of the public for which he works and to pretend a greater scorn than he feels. He cannot believe himself great unless he is misunderstood, and he hugs his unpopularity to himself as a sign of genius and arrives at that sublime affectation which answers praise of his work with an exclamation of dismay: "Is it as bad as that?" He invents new excesses and eccentricities to insure misunderstanding, and proclaims the doctrine that, as anything great must be incomprehensible, so anything incomprehensible must be great. And the public has taken him, at least partly, at his word. He may or may not be great, but he is certainly incomprehensible and probably a little mad. Until he succeeds the public looks upon the artist as a more or less harmless lunatic. When he succeeds it is willing to exalt him into a kind of god and to worship his eccentricities as a part of his divinity. So we arrive at a belief in the insanity of genius. What would Raphael have thought of such a notion, or that consummate man of the world, Titian? What would the serene and mighty Veronese have thought of it, or the cool, clear-seeing Velazquez? How his Excellency the Ambassador of his Most Catholic Majesty, glorious Peter Paul Rubens, would have laughed!

It is this lack of sympathy and understanding between the artist and his public—this fatal isolation of the artist—that is the cause of nearly all the shortcomings of modern art; of the weakness of what is known as official or academic art no less than of the extravagance of the art of opposition. The artist, being no longer a craftsman, working to order, but a kind of poet, expressing in loneliness his personal emotions, has lost his natural means of support. Governments, feeling a responsibility for the cultivation of art which was quite unnecessary in the days when art was spontaneously produced in answer to a natural demand, have tried to put an artificial support in its place. That the artist may show his wares and make himself known, they have created exhibitions; that he may be encouraged they have instituted medals and prizes; that he may not starve they have made government purchases. And these well-meant efforts have resulted in the creation of pictures which have no other purpose than to hang in exhibitions, to win medals, and to be purchased by the government and hung in those more permanent exhibitions which we call museums. For this purpose it is not necessary that a picture should have great beauty or great sincerity. It is necessary that it should be large in order to attract attention and sufficiently well drawn and executed to seem to deserve recognition. And so was evolved the salon picture, a thing created for no man's pleasure, not even the artist's; a thing which is neither the decoration of a public building nor the possible ornament of a private house; a thing which, after it has served its temporary purpose, is rolled up and stored in a loft or placed in a gallery where its essential emptiness becomes more and more evident as time goes on. Such government-encouraged art had at least the merit of a well-sustained and fairly high level of accomplishment in the more obvious elements of painting. But as exhibitions became larger and larger and the competition engendered by them grew fiercer, it became increasingly difficult to attract attention by mere academic merit. So the painters began to search for sensationalism of subject, and the typical salon picture, no longer decorously pompous, began to deal in blood and horror and sensuality. It was Regnault who began this sensation hunt, but it has been carried much further since his day than he can have dreamed of, and the modern salon picture is not only tiresome but detestable.

The salon picture, in its merits and its faults, is peculiarly French, but the modern exhibition has sins to answer for in other countries than France. In England it has been responsible for a great deal of sentimentality and anecdotage which has served to attract the attention of a public that could not be roused to interest in mere painting. Everywhere, even in this country, where exhibitions are relatively small and ill-attended, it has caused a certain stridency and blatancy, a keying up to exhibition pitch, a neglect of finer qualities for the sake of immediate effectiveness.

Under our modern conditions the exhibition has become a necessity, and it would be impossible for our artists to live or to attain a reputation without it. The giving of medals and prizes and the purchase of works of art by the state may be of more doubtful utility, though such efforts at the encouragement of art probably do more good than harm. But there is one form of government patronage that is almost wholly beneficial, and that the only form of it which we have in this country—the awarding of commissions for the decoration of public buildings. The painter of mural decorations is in the old historical position, in sound and natural relations to the public. He is doing something which is wanted and, if he continues to receive commissions, he may fairly assume that he is doing it in a way that is satisfactory. With the decorative or monumental sculptor he is almost alone among modern artists in being relieved of the necessity of producing something in the isolation of his studio and waiting to see if any one will care for it; of trying, against the grain, to produce something that he thinks may appeal to the public because it does not appeal to himself; or of attempting to bamboozle the public into buying what neither he nor the public really cares for. If he does his best he may feel that he is as fairly earning his livelihood as his fellow workmen, the blacksmith and the stonecutter, and is as little dependent as they upon either charity or humbug. The best that government has done for art in France is the commissioning of the great decorative paintings of Baudry and Puvis. In this country, also, governments, national, State, or municipal, are patronizing art in the best possible way, and in making buildings splendid for the people are affording opportunity for the creation of a truly popular art.

Without any artificial aid from the government the illustrator has a wide popular support and works for the public in a normal way; and, therefore, illustration has been one of the healthiest and most vigorous forms of modern art. The portrait-painter, too, is producing something he knows to be wanted, and, though his art has had to fight against the competition of the photograph and has been partially vulgarized by the struggle of the exhibitions, it has yet remained, upon the whole, comprehensible and human; so that much of the soundest art of the past century has gone into portraiture. It is the painters of pictures, landscape or genre, who have most suffered from the misunderstanding between artist and public. Without guidance some of them have hewed a path to deserved success. Others have wandered into strange byways and no-thoroughfares.

The nineteenth century is strewn with the wrecks of such misunderstood and misunderstanding artists, but it was about the sixties when their searching for a way began to lead them in certain clearly marked directions. There are three paths, in especial, which have been followed since then by adventurous spirits: the paths of æstheticism, of scientific naturalism, and of pure self-expression; the paths of Whistler, of Monet, and of Cézanne.

Whistler was an artist of refined and delicate talent with great weaknesses both in temperament and training; being also a very clever man and a brilliant controversialist, he proceeded to erect a theory which should prove his weaknesses to be so many virtues, and he nearly succeeded in convincing the world of its validity. Finding the representation of nature very difficult, he decided that art should not concern itself with representation but only with the creation of "arrangements" and "symphonies." Having no interest in the subject of pictures, he proclaimed that pictures should have no subjects and that any interest in the subject is vulgar. As he was a cosmopolitan with no local ties, he maintained that art had never been national; and as he was out of sympathy with his time, he taught that "art happens" and that "there never was an artistic period." According to the Whistlerian gospel, the artist not only has now no point of contact with the public, but he should not have and never has had any. He has never been a man among other men, but has been a dreamer "who sat at home with the women" and made pretty patterns of line and color because they pleased him. And the only business of the public is to accept "in silence" what he chooses to give them.

This kind of rootless art he practised. Some of the patterns he produced are delightful, but they are without imagination, without passion, without joy in the material and visible world—the dainty diversions of a dilettante. One is glad that so gracefully slender an art should exist, but if it has seemed great art to us it is because our age is so poor in anything better. To rank its creator with the abounding masters of the past is an absurdity.

In their efforts to escape from the dead-alive art of the salon picture, Monet and the Impressionists took an entirely different course. The gallery painter's perfunctory treatment of subject bored them, and they abandoned subject almost as entirely as Whistler had done. The sound if tame drawing and the mediocre painting of what they called official art revolted them as it revolted Whistler; but while he nearly suppressed representation they could see in art nothing but representation. They wanted to make that representation truer, and they tried to work a revolution in art by the scientific analysis of light and the invention of a new method of laying on paint. Instead of joining in Whistler's search for pure pattern they fixed their attention on facts alone, or rather on one aspect of the facts, and in their occupation with light and the manner of representing it they abandoned form almost as completely as they had abandoned significance and beauty.

So it happened that Monet could devote some twenty canvases to the study of the effects of light, at different hours of the day, upon two straw stacks in his farmyard. It was admirable practice, no doubt, and neither scientific analysis nor the study of technical methods is to be despised; but the interest of the public, after all, is in what an artist does, not in how he learns to do it. The twenty canvases together formed a sort of demonstration of the possibilities of different kinds of lighting. Any one of them, taken singly, is but a portrait of two straw stacks, and the world will not permanently or deeply care about those straw stacks. The study of light is, in itself, no more an exercise of the artistic faculties than the study of anatomy or the study of perspective; and while Impressionism has put a keener edge upon some of the tools of the artist, it has inevitably failed to produce a school of art.

After Impressionism, what? We have no name for it but Post-Impressionism. Such men as Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh recognized the sterility of Impressionism and of a narrow æstheticism, while they shared the hatred of the æsthetes and the Impressionists for the current art of the salons. No more than the æsthetes or the Impressionists were they conscious of any social or universal ideals that demanded expression. The æsthetes had a doctrine; the Impressionists had a method and a technic. The Post-Impressionists had nothing, and were driven to the attempt at pure self-expression—to the exaltation of the great god Whim. They had no training, they recognized no traditions, they spoke to no public. Each was to express, as he thought best, whatever he happened to feel or to think, and to invent, as he went along, the language in which he should express it. I think some of these men had the elements of genius in them and might have done good work; but their task was a heart-breaking and a hopeless one. An art cannot be improvised, and an artist must have some other guide than unregulated emotion. The path they entered upon had been immemorially marked "no passing"; for many of them the end of it was suicide or the madhouse.

But whatever the aberrations of these, the true Post-Impressionists—whatever the ugliness, the eccentricity, or the moral dinginess into which they were betrayed—I believe them to have been, in the main, honest if unbalanced and ill-regulated minds. Whatever their errors, they paid the price of them in poverty, in neglect, in death. With those who pretend to be their descendants to-day the case is different; they are not paying for their eccentricity or their madness, they are making it pay.

The enormous engine of modern publicity has been discovered by these men. They have learned to advertise, and they have found that morbidity, eccentricity, indecency, extremes of every kind and of any degree are capital advertisement. If one cannot create a sound and living art, one can at least make something odd enough to be talked about; if one cannot achieve enduring fame, one may make sure of a flaming notoriety. And, as a money-maker, present notoriety is worth more than future fame, for the speculative dealer is at hand. His interest is in "quick returns" and he has no wish to wait until you are famous—or dead—before he can sell anything you do. His process is to buy anything he thinks he can "boom," to "boom" it as furiously as possible, and to sell it before the "boom" collapses. Then he will exploit something else, and there's the rub. Once you have entered this mad race for notoriety, there is no drawing out of it. The same sensation will not attract attention a second time; you must be novel at any cost. You must exaggerate your exaggerations and out-Herod Herod, for others have learned how easy the game is to play, and are at your heels. It is no longer a matter of misunderstanding and being misunderstood by the public; it is a matter of deliberately flouting and outraging the public—of assuming incomprehensibility and antagonism to popular feeling as signs of greatness. And so is founded what Frederic Harrison has called the "shock-your-grandmother school."

It is with profound regret that one must name as one of the founders of this school an artist of real power, who has produced much admirable work—Auguste Rodin. At the age of thirty-seven he attained a sudden and resounding notoriety, and from that time he has been the most talked-of artist in Europe. He was a consummate modeller, a magnificent workman, but he had always grave faults and striking mannerisms. These faults and mannerisms he has latterly pushed to greater and greater extremes while neglecting his great gift, each work being more chaotic and fragmentary in composition, more hideous in type, more affected and emptier in execution, until he has produced marvels of mushiness and incoherence hitherto undreamed of and has set up as public monuments fantastically mutilated figures with broken legs or heads knocked off. Now, in his old age, he is producing shoals of drawings the most extraordinary of which few are permitted to see. Some selected specimens of them hang in a long row in the Metropolitan Museum, and I assure you, upon my word as a lifelong student of drawing, they are quite as ugly and as silly as they look. There is not a touch in them that has any truth to nature, not a line that has real beauty or expressiveness. They represent the human figure with the structure of a jellyfish and the movement of a Dutch doll; the human face with an expression I prefer not to characterize. If they be not the symptoms of mental decay, they can be nothing but the means of a gigantic mystification.

With Henri Matisse we have not to deplore the deliquescence of a great talent, for we have no reason to suppose he ever had any. It is true that his admirers will assure you he could once draw and paint as everybody does; what he could not do was to paint enough better than everybody does to make his mark in the world; and he was a quite undistinguished person until he found a way to produce some effect upon his grandmother the public by shocking her into attention. His method is to choose the ugliest models to be found; to put them into the most grotesque and indecent postures imaginable; to draw them in the manner of a savage, or a depraved child, or a worse manner if that be possible; to surround his figures with blue outlines half an inch wide; and to paint them in crude and staring colors, brutally laid on in flat masses. Then, when his grandmother begins to "sit up," she is told with a grave face that this is a reaction from naturalism, a revival of abstract line and color, a subjective art which is not the representation of nature but the expression of the artist's soul. No wonder she gasps and stares!

It seemed, two or three years ago, that the limit of mystification had been reached—that this comedy of errors could not be carried further; but human ingenuity is inexhaustible, and we now have whole schools, Cubists, Futurists, and the like, who joyously vie with each other in the creation of incredible pictures and of irreconcilable and incomprehensible theories. The public is inclined to lump them all together and, so far as their work is concerned, the public is not far wrong; yet in theory Cubism and Futurism are diametrically opposed to each other. It is not easy to get any clear conception of the doctrines of these schools, but, so far as I am able to understand them—and I have taken some pains to do so—they are something like this:

Cubism is static; Futurism is kinetic. Cubism deals with bulk; Futurism deals with motion. The Cubist, by a kind of extension of Mr. Berenson's doctrine of "tactile values," assumes that the only character of objects which is of importance to the artist is their bulk and solidity—what he calls their "volumes." Now the form in which volume is most easily apprehended is the cube; do we not measure by it and speak of the cubic contents of anything? The inference is easy: reduce all objects to forms which can be bounded by planes and defined by straight lines and angles; make their cubic contents measurable to the eye; transform drawing into a burlesque of solid geometry; and you have, at once, attained to the highest art. The Futurist, on the other hand, maintains that we know nothing but that things are in flux. Form, solidity, weight are illusions. Nothing exists but motion. Everything is changing every moment, and if anything were still we ourselves are changing. It is, therefore, absurd to give fixed boundaries to anything or to admit of any fixed relations in space. If you are trying to record your impression of a face it is certain that by the time you have done one eye the other eye will no longer be where it was—it may be at the other side of the room. You must cut nature into small bits and shuffle them about wildly if you are to reproduce what we really see.

Whatever its extravagance, Cubism remains a form of graphic art. However pedantic and ridiculous its transformation of drawing, it yet recognizes the existence of drawing. Therefore, to the Futurist, Cubism is reactionary. What difference does it make, he asks, whether you draw a head round or square? Why draw a head at all? The Futurist denies the fundamental postulates of the art of painting. Painting has always, and by definition, represented upon a surface objects supposed to lie beyond it and to be seen through it. Futurism pretends to place the spectator inside the picture and to represent things around him or behind him as well as those in front of him. Painting has always assumed the single moment of vision, and, though it has sometimes placed more than one picture on the same canvas, it has treated each picture as seen at a specific instant of time. Futurism attempts systematically to combine the past and the future with the present, as if all the pictures in a cinematograph film were to be printed one over the other; to paint no instant but to represent the movement of time. It aims at nothing less than the abrogation of all recognized laws, the total destruction of all that has hitherto passed for art.

Do you recall the story of the man who tried to count a litter of pigs, but gave it up because one little pig ran about so fast that he could not be counted? One finds oneself in somewhat the same predicament when one tries to describe these "new movements" in art. The movement is so rapid and the men shift their ground so quickly that there is no telling where to find them. You have no sooner arrived at some notion of the difference between Cubism and Futurism than you find your Cubist doing things that are both Cubist and Futurist, or neither Cubist nor Futurist, according as you look at them. You find things made up of geometrical figures to give volume, yet with all the parts many times repeated to give motion. You find things that have neither bulk nor motion but look like nothing so much as a box of Chinese tangrams scattered on a table. Finally, you have assemblages of lines that do not draw anything, even cubes or triangles; and we are assured that there is now a newest school of all, called Orphism, which, finding still some vestiges of intelligibility in any assemblage of lines, reduces everything to shapeless blotches. Probably the first of Orphic pictures was that produced by the quite authentic donkey who was induced to smear a canvas by lashing a tail duly dipped in paint. It was given a title as Orphic as the painting, was accepted by a jury anxious to find new forms of talent, and was hung in the Salon d'Automne.

In all this welter of preposterous theories there is but one thing constant—one thing on which all these theorists are agreed. It is that all this strange stuff is symbolic and shadows forth the impressions and emotions of the artist: represents not nature but his feeling about nature; is the expression of his mind or, as they prefer to call it, his soul. It may be so. All art is symbolic; images are symbols; words are symbols; all communication is by symbols. But if a symbol is to serve any purpose of communication between one mind and another it must be a symbol accepted and understood by both minds. If an artist is to choose his symbols to suit himself, and to make them mean anything he chooses, who is to say what he means or whether he means anything? If a man were to rise and recite, with a solemn voice, words like "Ajakan maradak tecor sosthendi," would you know what he meant? If he wished you to believe that these symbols express the feeling of awe caused by the contemplation of the starry heavens, he would have to tell you so in your own language; and even then you would have only his word for it. He may have meant them to express that, but do they? The apologists of the new schools are continually telling us that we must give the necessary time and thought to learn the language of these men before we condemn them. Why should we? Why should not they learn the universal language of art? It is they who are trying to say something. When they have learned to speak that language and have convinced us that they have something to say in it which is worth listening to, then, and not till then, we may consent to such slight modification of it as may fit it more closely to their thought.

If these gentlemen really believe that their capriciously chosen symbols are fit vehicles for communication with others, why do they fall back on that old, old symbol, the written word? Why do they introduce, in the very midst of a design in which everything else is dislocated, a name or a word in clear Roman letters? Or why do they give their pictures titles and, lest you should neglect to look in the catalogue, print the title quite carefully and legibly in the corner of the picture itself? They know that they must set you to hunting for their announced subject or you would not look twice at their puzzles.

Now, there is only one word for this denial of all law, this insurrection against all custom and tradition, this assertion of individual license without discipline and without restraint; and that word is "anarchy." And, as we know, theoretic anarchy, though it may not always lead to actual violence, is a doctrine of destruction. It is so in art, and these artistic anarchists are found proclaiming that the public will never understand or accept their art while anything remains of the art of the past, and demanding that therefore the art of the past shall be destroyed. It is actual, physical destruction of pictures and statues that they call for, and in Italy, that great treasury of the world's art, has been raised the sinister cry: "Burn the museums!" They have not yet taken to the torch, but if they were sincere they would do it; for their doctrine calls for nothing less than the reduction of mankind to a state of primitive savagery that it may begin again at the beginning.

Fortunately, they are not sincere. There may be among them those who honestly believe in that exaltation of the individual and that revolt against all law which is the danger of our age. But, for the most part, if they have broken from the fold and "like sheep have gone astray," they have shown a very sheep-like disposition to follow the bell-wether. They are fond of quoting a saying of Gauguin's that "one must be either a revolutionist or a plagiary"; but can any one tell these revolutionists apart? Can any one distinguish among them such definite and logically developed personalities as mark even schoolmen and "plagiarists" like Meissonier and Gérôme? If any one of these men stood alone, one might believe his eccentricities to be the mark of an extreme individuality; one cannot believe it when one finds the same eccentricities in twenty of them.

No, it is not for the sake of unhampered personal development that young artists are joining these new schools; it is because they are offered a short cut to a kind of success. As there are no more laws and no more standards, there is nothing to learn. The merest student is at once set upon a level with the most experienced of his instructors, and boys and girls in their teens are hailed as masters. Art is at last made easy, and there are no longer any pupils, for all have become teachers. To borrow Doctor Johnson's phrase, "many men, many women, and many children" could produce art after this fashion; and they do.

So right are the practitioners of this puerile art in their proclaimed belief that the public will never accept it while anything else exists, that one might be willing to treat it with the silent contempt it deserves were it not for the efforts of certain critics and writers for the press to convince us that it ought to be accepted. Some of these men seem to be intimidated by the blunders of the past. Knowing that contemporary criticism has damned almost every true artist of the nineteenth century, they are determined not to be caught napping; and they join in shouts of applause as each new harlequin steps upon the stage. They forget that it is as dangerous to praise ignorantly as to blame unjustly, and that the railer at genius, though he may seem more malevolent, will scarce appear so ridiculous to posterity as the dupe of the mountebank. Others of them are, no doubt, honest victims of that illusion of progress to which we are all more or less subject—to that ingrained belief that all evolution is upward and that the latest thing must necessarily be the best. They forget that the same process which has relieved man of his tail has deprived the snake of his legs and the kiwi of his wings. They forget that art has never been and cannot be continuously progressive; that it is only the sciences connected with art that are capable of progress; and that the "Henriade" is not a greater poem than the "Divine Comedy" because Voltaire has learned the falsity of the Ptolemaic astronomy. Finally, these writers, like other people, desire to seem knowing and clever; and if you appear to admire vastly what no one else understands you pass for a clever man.

I have looked through a good deal of the writings of these "up-to-date" critics in the effort to find something like an intelligible argument or a definite statement of belief. I have found nothing but the continually repeated assumption that these new movements, in all their varieties, are "living" and "vital." I can find no grounds stated for this assumption and can suppose only that what is changing with great rapidity is conceived to be alive; yet I know nothing more productive of rapid changes than putrefaction.

Do not be deceived. This is not vital art, it is decadent and corrupt. True art has always been the expression by the artist of the ideals of his time and of the world in which he lived—ideals which were his own because he was a part of that world. A living and healthy art never has existed and never can exist except through the mutual understanding and co-operation of the artist and his public. Art is made for man and has a social function to perform. We have a right to demand that it shall be both human and humane; that it shall show some sympathy in the artist with our thoughts and our feelings; that it shall interpret our ideals to us in that universal language which has grown up in the course of ages. We have a right to reject with pity or with scorn the stammerings of incompetence, the babble of lunacy, or the vaporing of imposture. But mutual understanding implies a duty on the part of the public as well as on the part of the artist, and we must give as well as take. We must be at the pains to learn something of the language of art in which we bid the artist speak. If we would have beauty from him we must sympathize with his aspiration for beauty. Above all, if we would have him interpret for us our ideals we must have ideals worthy of such interpretation. Without this co-operation on our part we may have a better art than we deserve, for noble artists will be born, and they will give us an art noble in its essence however mutilated and shorn of its effectiveness by our neglect. It is only by being worthy of it that we can hope to have an art we may be proud of—an art lofty in its inspiration, consummate in its achievement, disciplined in its strength.

Jean François Millet, who lived hard and died poor, is now perhaps the most famous artist of the nineteenth century. His slightest work is fought for by dealers and collectors, and his more important pictures, if they chance to change hands, bring colossal and almost incredible prices. And of all modern reputations his, so far as we can see, seems most likely to be enduring. If any painter of the immediate past is definitively numbered with the great masters, it is he. Yet the popular admiration for his art is based on a I misapprehension almost as profound as that of those contemporaries who decried and opposed him. They thought him violent, rude, ill-educated, a "man of the woods," a revolutionist, almost a communist. We are apt to think of him as a gentle sentimentalist, a soul full of compassion for the hard lot of the poor, a man whose art achieves greatness by sheer feeling rather than by knowledge and intellect. In spite of his own letters, in spite of the testimony of many who knew him well, in spite of more than one piece of illuminating criticism, these two misconceptions endure; and, for the many, Millet is still either the painter of "The Man with the Hoe," a powerful but somewhat exceptional work, or the painter of "L'Angelus," precisely the least characteristic picture he ever produced. There is a legendary Millet, in many ways a very different man from the real one, and, while the facts of his life are well known and undisputed, the interpretation of them is colored by preconceptions and strained to make them fit the legend.

Altogether too much, for instance, has been made of the fact that Millet was born a peasant. He was so, but so were half the artists and poets who come up to Paris and fill the schools and the cafés of the student quarters. To any one who has known these young rapins, and wondered at the grave and distinguished members of the Institute into which many of them have afterward developed, it is evident that this studious youth—who read Virgil in the original and Homer and Shakespeare and Goethe in translations—probably had a much more cultivated mind and a much sounder education than most of his fellow students under Delaroche. Seven years after this Norman farmer's son came to Paris, with a pension of 600 francs voted by the town council of Cherbourg, the son of a Breton sabot-maker followed him there with a precisely similar pension voted by the town council of Roche-sur-Yon; and the pupil of Langlois had had at least equal opportunities with the pupil of Sartoris. Both cases were entirely typical of French methods of encouraging the fine arts, and the peasant origin of Millet is precisely as significant as the peasant origin of Baudry.

Baudry persevered in the course marked out for him and, after failing three times, received the Prix de Rome and became the pensioner of the state. Millet took umbrage at Delaroche's explanation that his support was already pledged to another candidate for the prize, and left the atelier of that master after little more than a year's work. But that he had already acquired most of what was to be learned there is shown, if by nothing else, by the master's promise to push him for the prize the year following. This was in 1838, and for a year or two longer Millet worked in the life classes of Suisse and Boudin without a master. His pension was first cut down and then withdrawn altogether, and he was thrown upon his own resources. His struggles and his poverty during the next few years were those of many a young artist, aggravated, in his case, by two imprudent marriages. But during all the time that he was painting portraits in Cherbourg or little nudes in Paris he was steadily gaining reputation and making friends. If we had not the pictures themselves to show us how able and how well-trained a workman he was, the story told us by Wyatt Eaton, in "Modern French Masters," would convince us. It was in the last year of Millet's life that he told the young American how, in his early days, a dealer would come to him for a picture and, "having nothing painted, he would offer the dealer a book and ask him to wait for a little while that he might add a few touches to the picture." He would then go into his studio and take a fresh canvas, or a panel, and in two hours bring out a little nude figure, which he had painted during that time, and for which he would receive twenty or twenty-five francs. It was the work of this time that Diaz admired for its color and its "immortal flesh painting"; that caused Guichard, a pupil of Ingres, to tell his master that Millet was the finest draughtsman of the new school; that earned for its author the title of "master of the nude."

He did all kinds of work in these days, even painting signs and illustrating sheet music, and it was all capital practice for a young man, but it was not what he wanted to do. A great deal has been made of the story of his overhearing some one speak of him as "a fellow who never paints anything but naked women," and he is represented as undergoing something like a sudden conversion and as resolving to "do no more of the devil's work." As a matter of fact, he had, from the first, wanted to paint "men at work in the fields," with their "fine attitudes," and he only tried his hand at other things because he had his living to earn. Sensier saw what seems to have been the first sketch for "The Sower" as early as 1847, and it existed long before that, while "The Winnower" was exhibited in 1848; and the overheard conversation is said to have taken place in 1849. There was nothing indecent or immoral in Millet's early work, and the best proof that he felt no moral reprobation for the painting of the nude—as what true painter, especially in France, ever did?—is that he returned to it in the height of his power and, in the picture of the little "Goose Girl" (Pl. 1) by the brook side, her slim, young body bared for the bath, produced the loveliest of his works. No, what happened to Millet in 1849 was simply that he resolved to do no more pot-boiling, to consult no one's taste but his own, to paint what he pleased and as he pleased, if he starved for it. He went to Barbizon for a summer's holiday and to escape the cholera. He stayed there because living was cheap and the place was healthful, and because he could find there the models and the subjects on which he built his highly abstract and ideal art.

At Barbizon he neither resumed the costume nor led the life of a peasant. He wore sabots, as hundreds of other artists have done, before and since, when living in the country in France. Sabots are very cheap and very dry and not uncomfortable when you have acquired the knack of wearing them. In other respects he dressed and lived like a small bourgeois, and was monsieur to the people about him. Barbizon was already a summer resort for artists before he came there, and the inn was full of painters; while others, of whom Rousseau was one, were settled there more or less permanently. It is but a short distance from Paris, and the exhibitions and museums were readily accessible. The life that Millet lived there was that of many poor, self-respecting, hard-working artists, and if he had been a landscape painter that life would never have seemed in any way exceptional. It is only because he was a painter of the figure that it seems odd he should have lived in the country; only because he painted peasants that he has been thought of as a peasant himself. If he accepted the name, with a kind of pride, it was in protest against the frivolity and artificiality of the fashionable art of the day. But if too much has been made of Millet's peasant origin, perhaps hardly enough has been made of his race. It is at least interesting that the two Frenchmen whose art has most in common with his, Nicolas Poussin and Pierre Corneille, should have been Normans like himself. In the severely restrained, grandly simple, profoundly classical work of these three men, that hard-headed, strong-handed, austere, and manly race has found its artistic expression.

For Millet is neither a revolutionary nor a sentimentalist, nor even a romanticist; he is essentially a classicist of the classicists, a conservative of the conservatives, the one modern exemplar of the grand style. It is because his art is so old that it was "too new" for even Corot to understand it; because he harked back beyond the pseudoclassicism of his time to the great art of the past, and was classic as Phidias and Giotto and Michelangelo were classic, that he seemed strange to his contemporaries. In everything he was conservative. He hated change; he wanted things to remain as they had always been. He did not especially pity the hard lot of the peasant; he considered it the natural and inevitable lot of man who "eats bread in the sweat of his brow." He wanted the people he painted "to look as if they belonged to their place—as if it would be impossible for them ever to think of being anything else but what they are." In the herdsman and the shepherd, the sower and the reaper, he saw the immemorial types of humanity whose labors have endured since the world began and were essentially what they now are when Virgil wrote his "Georgics" and when Jacob kept the flocks of Laban. This is the note of all his work. It is the permanent, the essential, the eternally significant that he paints. The apparent localization of his subjects in time and place is an illusion. He is not concerned with the nineteenth century or with Barbizon but with mankind. At the very moment when the English Pre-raphaelites were trying to found a great art on the exhaustive imitation of natural detail, he eliminated detail as much as possible. At the very beginning of our modern preoccupation with the direct representation of facts, he abandoned study from the model almost entirely and could say that he "had never painted from nature." His subjects would have struck the amiable Sir Joshua as trivial, yet no one has ever more completely followed that writer's precepts. His confession of faith is in the words, "One must be able to make use of the trivial for the expression of the sublime"; and this painter of "rustic genre" is the world's greatest master of the sublime after Michelangelo.

The comparison with Michelangelo is inevitable and has been made again and again by those who have felt the elemental grandeur of Millet's work. As a recent writer has remarked: "An art highly intellectualized, so as to convey a great idea with the lucidity of language, must needs be controlled by genius akin to that which inspired the ceiling paintings of the Sistine Chapel."[A] This was written of the Trajanic sculptors, whose works both Michelangelo and Millet studied and admired, and indeed it is to this old Roman art, or to the still older art of Greece, that one must go for the truest parallel of Millet's temper and his manner of working. He was less impatient, less romantic and emotional than Michelangelo; he was graver, quieter, more serene; and if he had little of the Greek sensuousness and the Greek love of physical beauty, he had much of the antique clarity and simplicity. To express his idea clearly, logically, and forcibly; to make a work of art that should be "all of a piece" and in which "things should be where they are for a purpose"; to admit nothing for display, for ornament, even for beauty, that did not necessarily and inevitably grow out of his central theme, and to suppress with an iron rigidity everything useless or superfluous—this was his constant and conscious effort. It is an ideal eminently austere and intellectual—an ideal, above all, especially and eternally classic.

[A] Eugénie Strong, "Roman Sculpture," p. 224.

Take, for an instance, the earliest of his masterpieces, the first great picture by which he marked his emancipation and his determination henceforth to produce art as he understood it without regard to the preferences of others. Many of his preliminary drawings and studies exist and we can trace, more or less clearly, the process by which the final result was arrived at. At first we have merely a peasant sowing grain; an everyday incident, truly enough observed but nothing more. Gradually the background is cut down, the space restricted, the figure enlarged until it fills its frame as a metope of the Parthenon is filled. The gesture is ever enlarged and given more sweep and majesty, the silhouette is simplified and divested of all accidental or insignificant detail. A thousand previous observations are compared and resumed in one general and comprehensive formula, and the typical has been evolved from the actual. What generations of Greek sculptors did in their slow perfectioning of certain fixed types he has done almost at once. We have no longer a man sowing, but "The Sower" (Pl. 2), justifying the title he instinctively gave it by its air of permanence, of inevitability, of universality. All the significance which there is or ever has been for mankind in that primæval action of sowing the seed is crystallized into its necessary expression. The thing is done once for all, and need never—can never be done again. Has any one else had this power since Michelangelo created his "Adam"?

If even Millet never again attained quite the august impressiveness of this picture it is because no other action of rustic man has so wide or so deep a meaning for us as this of sowing. All the meaning there is in an action he could make us feel with entire certainty, and always he proceeds by this method of elimination, concentration, simplification, insistence on the essential and the essential only. One of the most perfect of all his pictures—more perfect than "The Sower" on account of qualities of mere painting, of color, and of the rendering of landscape, of which I shall speak later—is "The Gleaners" (Pl. 3). Here one figure is not enough to express the continuousness of the movement; the utmost simplification will not make you feel, as powerfully as he wishes you to feel it, the crawling progress, the bending together of back and thighs, the groping of worn fingers in the stubble. The line must be reinforced and reduplicated, and a second figure, almost a facsimile of the first, is added. Even this is not enough. He adds a third figure, not gathering the ear, but about to do so, standing, but stooped forward and bounded by one great, almost uninterrupted curve from the peak of the cap over her eyes to the heel which half slips out of the sabot, and the thing is done. The whole day's work is resumed in that one moment. The task has endured for hours and will endure till sunset, with only an occasional break while the back is half-straightened—there is not time to straighten it wholly. It is the triumph of significant composition, as "The Sower" is the triumph of significant draughtsmanship.

Or, when an action is more complicated and difficult of suggestion, as is that, for instance, of digging, he takes it at the beginning and at the end, as in "The Spaders" (Pl. 4), and makes you understand everything between. One man is doubled over his spade, his whole weight brought to bear on the pressing foot which drives the blade into the ground. The other, with arms outstretched, gives the twisting motion which lets the loosened earth fall where it is to lie. Each of these positions is so thoroughly understood and so definitely expressed that all the other positions of the action are implied in them. You feel the recurrent rhythm of the movement and could almost count the falling of the clods.

So far did Millet push the elimination of non-essentials that his heads have often scarcely any features, his hands, one might say, are without fingers, and his draperies are so simplified as to suggest the witty remark that his peasants are too poor to afford any folds in their garments. The setting of the great, bony planes of jaw and cheek and temple, the bulk and solidity of the skull, and the direction of the face—these were, often enough, all he wanted of a head. Look at the hand of the woman in "The Potato Planters" (Pl. 5), or at those of the man in the same picture, and see how little detail there is in them, yet how surely the master's sovereign draughtsmanship has made you feel their actual structure and function! And how inevitably the garments, with their few and simple folds, mould and accent the figures beneath them, "becoming, as it were, a part of the body and expressing, even more than the nude, the larger and simpler forms of nature"! How explicitly the action of the bodies is registered, how perfectly the amount of effort apparent is proportioned to the end to be attained! One can feel, to an ounce, it seems, the strain upon the muscles implied by that hoe-full of earth. Or look at the easier attitude of "The Grafter" (Pl. 6), engaged upon his gentler task, and at the monumental silhouette of the wife, standing there, babe in arms, a type of eternal motherhood and of the fruitfulness to come.

Oftener than anything, perhaps, it was the sense of weight that interested Millet. It is the adjustment of her body to the weight of the child she carries that gives her statuesque pose to the wife of the grafter. It is the drag of the buckets upon the arms that gives her whole character to the magnificent "Woman Carrying Water," in the Vanderbilt collection. It is the erect carriage, the cautious, rhythmic walk, keeping step together, forced upon them by the sense of weight, which gives that gravity and solemnity to the bearers of "The New-Born Calf" (Pl. 7), which was ridiculed by Millet's critics as more befitting the bearers of the bull Apis or the Holy Sacrament. The artist himself was explicit in this instance as in that of the "Woman Carrying Water." "The expression of two men carrying a load on a litter," he says, "naturally depends on the weight which rests upon their arms. Thus, if the weight is equal, their expression will be the same, whether they bear the Ark of the Covenant or a calf, an ingot of gold or a stone." Find that expression, whether in face or figure, render it clearly, "with largeness and simplicity," and you have a great, a grave, a classic work of art. "We are never so truly Greek," he said, "as when we are simply painting our own impressions." Certainly his own way of painting his impressions was more Greek than anything else in the whole range of modern art.

In the epic grandeur of such pictures as these there is something akin to sadness, though assuredly Millet did not mean them to be sad. Did he not say of the "Woman Carrying Water": "I have avoided, as I always do, with a sort of horror, everything that might verge on the sentimental"? He wished her to seem "to do her work simply and cheerfully ... as a part of her daily task and the habit of her life." And he was not always in the austere and epical mood. He could be idyllic as well, and if he could not see "the joyous side" of life or nature he could feel and make us feel the charm of tranquillity. Indeed, this remark of his about the joyous side of things was made in the dark, early days when life was hardest for him. He broadened in his view as he grew older and conditions became more tolerable, and he has painted a whole series of little pictures of family life and of childhood that, in their smiling seriousness, are endlessly delightful. The same science, the same thoughtfulness, the same concentration and intellectual grasp that defined for us the superb gesture of "The Sower" have gone to the depiction of the adorable uncertainty, between walking and falling, of those "First Steps" (Pl. 8) from the mother's lap to the outstretched arms of the father; and the result, in this case as in the other, is a thing perfectly and permanently expressed. Whatever Millet has done is done. He has "characterized the type," as it was his dream to do, and written "hands off" across his subject for all future adventurers.

Finally, he rises to an almost lyric fervor in that picture of the little "Goose Girl" bathing, which is one of the most purely and exquisitely beautiful things in art. In this smooth, young body quivering with anticipation of the coolness of the water; in these rounded, slender limbs with their long, firm, supple lines; in the unconscious, half-awkward grace of attitude and in the glory of sunlight splashing through the shadow of the willows, there is a whole song of joy and youth and the goodness of the world. The picture exists in a drawing or pastel, which has been photographed by Braun, as well as in the oil-painting, and Millet's habit of returning again and again to a favorite subject renders it difficult to be certain which is the earlier of the two; but I imagine this drawing to be a study for the picture. At first sight the figure in it is more obviously beautiful than in the other version, and it is only after a time that one begins to understand the changes that the artist was impelled to make. It is almost too graceful, too much like an antique nymph. No one could find any fault with it, but by an almost imperceptible stiffening of the line here and there, a little greater turn of the foot upon the ankle and of the hand upon the wrist, the figure in the painting has been given an accent of rusticity that makes it more human, more natural, and more appealing. She is no longer a possible Galatea or Arethusa, she is only a goose girl, and we feel but the more strongly on that account the eternal poem of the healthy human form.

The especial study of the nineteenth century was landscape, and Millet was so far a man of his time that he was a great landscape painter; but his treatment of landscape was unlike any other, and, like his own treatment of the figure, in its insistence on essentials, its elimination of the accidental, its austere and grand simplicity. I have heard, somewhere, a story of his saying, in answer to praise of his work or inquiry as to his meaning: "I was trying to express the difference between the things that lie flat and the things that stand upright." That is the real motive of one of his masterpieces—one that in some moods seems the greatest of them all—"The Shepherdess" (Pl. 9), that is, or used to be, in the Chauchard collection. In this nobly tranquil work, in which there is no hint of sadness or revolt, are to be found all his usual inevitableness of composition and perfection of draughtsmanship—note the effect of repetition in the sheep, "forty feeding like one"—but the glory of the picture is in the infinite recession of the plain that lies flat, the exact notation of the successive positions upon it of the things that stand upright, from the trees and the hay wain in the extreme distance, almost lost in sky, through the sheep and the sheep-dog and the shepherdess herself, knitting so quietly, to the dandelions in the foreground, each with its "aureole" of light. Of these simple, geometrical relations, and of the enveloping light and air by which they are expressed, he has made a hymn of praise.

The background of "The Gleaners," with its baking stubble-field under the midday sun, its grain stacks and laborers and distant farmstead, all tremulous in the reflected waves of heat, indistinct and almost indecipherable yet unmistakable, is nearly as wonderful; and no one has ever so rendered the solemnity and the mystery of night as has he in the marvellous "Sheepfold" of the Walters collection. But the greatest of all his landscapes—one of the greatest landscapes ever painted—is his "Spring" (Pl. 10), of the Louvre, a pure landscape this time, containing no figure. In the intense green of the sunlit woods against the black rain-clouds that are passing away, in the jewel-like brilliancy of the blossoming apple-trees, and the wet grass in that clear air after the shower; in the glorious rainbow drawn in dancing light across the sky, we may see, if anywhere in art, some reflection of the "infinite splendors" which Millet tells us he saw in nature.

In the face of such results as these it seems absurd to discuss the question whether or not Millet was technically a master of his trade, as if the methods that produced them could possibly be anything but good methods for the purpose; but it is still too much the fashion to say and think that the great artist was a poor painter—to speak slightingly of his accomplishment in oil-painting and to seem to prefer his drawings and pastels to his pictures. We have seen that he was a supremely able technician in his pot-boiling days and that the color and handling of his early pictures were greatly admired by so brilliant a virtuoso as Diaz. But this "flowery manner" would not lend itself to the expression of his new aims and he had to invent another. He did so stumblingly at first, and the earliest pictures of his grand style have a certain harshness and ruggedness of surface and heaviness of color which his critics could not forgive any more than the Impressionists, who have outdone that ruggedness, can forgive him his frequent use of a warm general tone inclining to brownness. His ideal of form and of composition he possessed complete from the beginning; his mastery of light and color and the handling of materials was slower of acquirement; but he did acquire it, and in the end he is as absolute a master of painting as of drawing. He did not see nature in blue and violet, as Monet has taught us to see it, and little felicities and facilities of rendering, and anything approaching cleverness or the parade of virtuosity he hated; but he knew just what could be done with thick or thin painting, with opaque or transparent pigment, and he could make his few and simple colors say anything he chose. In his mature work there is a profound knowledge of the means to be employed and a great economy in their use, and there is no approach to indiscriminate or meaningless loading. "Things are where they are for a purpose," and if the surface of a picture is rough in any place it is because just that degree of roughness was necessary to attain the desired effect. He could make mere paint express light as few artists have been able to do—"The Shepherdess" is flooded with it—and he could do this without any sacrifice of the sense of substance in the things on which the light falls. If some of his canvases are brown it is because brown seemed to him the appropriate note to express what he had to say; "The Gleaners" glows with almost the richness of a Giorgione, and other pictures are honey-toned or cool and silvery or splendidly brilliant. And in whatever key he painted, the harmony of his tones and colors is as large, as simple, and as perfect as the harmony of his lines and masses.

But if we cannot admit that Millet's drawings are better than his paintings, we may be very glad he did them. His great epic of the soil must have lacked many episodes, perhaps whole books and cantos, if it had been written only in the slower and more elaborate method. The comparative slightness and rapidity of execution of his drawings and pastels enabled him to register many inventions and observations that we must otherwise have missed, and many of these are of the highest value. His long training in seizing the essential in anything he saw enabled him, often, to put more meaning into a single rapid line than another could put into a day's painful labor, and some of his slightest sketches are astonishingly and commandingly expressive. Other of his drawings were worked out and pondered over almost as lovingly as his completest pictures. But so instinctively and inevitably was he a composer that everything he touched is a complete whole—his merest sketch or his most elaborated design is a unit. He has left no fragments. His paintings, his countless drawings, his few etchings and woodcuts are all of a piece. About everything there is that air of finality which marks the work destined to become permanently a classic.

Here and there, by one or another writer, most or all of what I have been trying to say has been said already. It is the more likely to be true. And if these true things have been said, many other things have been said also which seem to me not so true, or little to the purpose, so that the image I have been trying to create must differ, for better or for worse, from that which another might have made. At least I may have looked at the truth from a slightly different angle and so have shown it in a new perspective. And, at any rate, it is well that true things should be said again from time to time. It can do no harm that one more person should endeavor to give a reason for his admiration of a great and true artist and should express his conviction that among the world's great masters the final place of Jean François Millet is not destined to be the lowest.

[B] Read before the joint meeting of The American Academy of Arts and Letters and The National Institute of Arts and Letters, December 13, 1912.

In these days all of us, even Academicians, are to some extent believers in progress. Our golden age is no longer in the past, but in the future. We know that our early ancestors were a race of wretched cave-dwellers, and we believe that our still earlier ancestors were possessed of tails and pointed ears. Having come so far, we are sometimes inclined to forget that not every step has been an advance and to entertain an illogical confidence that each future step must carry us still further forward; having indubitably progressed in many things, we think of ourselves as progressing in all. And as the pace of progress in science and in material things has become more and more rapid, we have come to expect a similar pace in art and letters, to imagine that the art of the future must be far finer than the art of the present or than that of the past, and that the art of one decade, or even of one year, must supersede that of the preceding decade or the preceding year, as the 1913 model in automobiles supersedes the model of 1912. More than ever before "To have done is to hang quite out of fashion," and the only title to consideration is to do something quite obviously new or to proclaim one's intention of doing something newer. The race grows madder and madder. It was scarce two years since we first heard of "Cubism" when the "Futurists" were calling the "Cubists" reactionary. Even the gasping critics, pounding manfully in the rear, have thrown away all impedimenta of traditional standards in the desperate effort to keep up with what seems less a march than a stampede.

But while we talk so loudly of progress in the arts we have an uneasy feeling that we are not really progressing. If our belief in our own art were as full-blooded as was that of the great creative epochs, we should scarce be so reverent of the art of the past. It is, perhaps, a sign of anæmia that we have become founders of museums and conservers of old buildings. If we are so careful of our heritage, it is surely from some doubt of our ability to replace it. When art has been vigorously alive it has been ruthless in its treatment of what has gone before. No cathedral builder thought of reconciling his own work to that of the builder who preceded him; he built in his own way, confident of its superiority. And when the Renaissance builder came, in his turn, he contemptuously dismissed all mediæval art as "Gothic" and barbarous, and was as ready to tear down an old façade as to build a new one. Even the most cock-sure of our moderns might hesitate to emulate Michelangelo in his calm destruction of three frescoes by Perugino to make room for his own "Last Judgment." He, at least, had the full courage of his convictions, and his opinion of Perugino is of record.

Not all of us would consider even Michelangelo's arrogance entirely justified, but it is not only the Michelangelos who have had this belief in themselves. Apparently the confidence of progress has been as great in times that now seem to us decadent as in times that we think of as truly progressive. The past, or at least the immediate past, has always seemed "out of date," and each generation, as it made its entrance on the stage, has plumed itself upon its superiority to that which was leaving it. The architect of the most debased baroque grafted his "improvements" upon the buildings of the high Renaissance with an assurance not less than that with which David and his contemporaries banished the whole charming art of the eighteenth century. Van Orley and Frans Floris were as sure of their advance upon the ancient Flemish painting of the Van Eycks and of Memling as Rubens himself must have been of his advance upon them.

We can see plainly enough that in at least some of these cases the sense of progress was an illusion. There was movement, but it was not always forward movement. And if progress was illusory in some instances, may it not, possibly, have been so in all? It is at least worth inquiry how far the fine arts have ever been in a state of true progress, going forward regularly from good to better, each generation building on the work of its predecessors and surpassing that work, in the way in which science has normally progressed when material conditions were favorable.

If, with a view to answering this question, we examine, however cursorily, the history of the five great arts, we shall find a somewhat different state of affairs in the case of each. In the end it may be possible to formulate something like a general rule that shall accord with all the facts. Let us begin with the greatest and simplest of the arts, the art of poetry.

In the history of poetry we shall find less evidence of progress than anywhere else, for it will be seen that its acknowledged masterpieces are almost invariably near the beginning of a series rather than near the end. Almost as soon as a clear and flexible language has been formed by any people, a great poem has been composed in that language, which has remained not only unsurpassed, but unequalled, by any subsequent work. Homer is for us, as he was for the Greeks, the greatest of their poets; and if the opinion could be taken of all cultivated readers in those nations that have inherited the Greek tradition, it is doubtful whether he would not be acclaimed the greatest poet of the ages. Dante has remained the first of Italian poets, as he was one of the earliest. Chaucer, who wrote when our language was transforming itself from Anglo-Saxon into English, has still lovers who are willing for his sake to master what is to them almost a foreign tongue, and yet other lovers who ask for new translations of his works into our modern idiom; while Shakespeare, who wrote almost as soon as that transformation had been accomplished, is universally reckoned one of the greatest of world poets. There have, indeed, been true poets at almost all stages of the world's history, but the pre-eminence of such masters as these can hardly be questioned, and if we looked to poetry alone for a type of the arts, we should almost be forced to conclude that art is the reverse of progressive. We should think of it as gushing forth in full splendor when the world is ready for it, and as unable ever again to rise to the level of its fount.