The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Dead Boxer, by William Carleton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Dead Boxer

The Works of William Carleton, Volume Two

Author: William Carleton

Illustrator: M. L. Flanery

Release Date: June 7, 2005 [EBook #16007]

Last Updated: March 1, 2018

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DEAD BOXER ***

Produced by David Widger

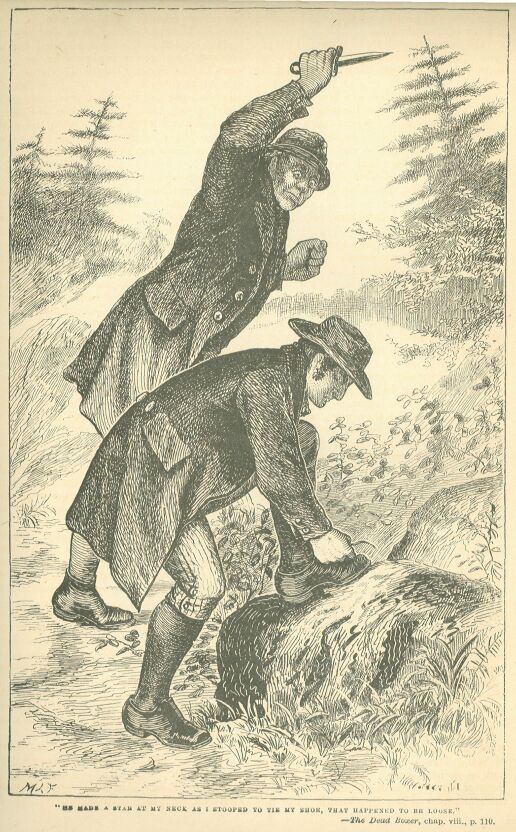

List of Illustrations

One evening in the beginning of the eighteenth century—as nearly as we can conjecture, the year might be that of 1720—some time about the end of April, a young man named Lamh Laudher O'Rorke, or Strong-handed O'Eorke, was proceeding from his father's house, with a stout oaken cudgel in his hand, towards an orchard that stood at the skirt of a country town, in a part of the kingdom which, for the present, shall be nameless. Though known by the epithet of Lamh Laudher, his Christian name was John; but in those time(s) Irish families of the same name were distinguished from each other by some indicative of their natural position, physical power, complexion, or figure. One, for instance, was called Parra Ghastha, or swift Paddy, from his fleetness of foot; another, Shaun Buie, or yellow Jack, from his bilious look; a third, Micaul More, or big Michael, from his uncommon size; and a fourth, Sheemus Ruah, or red James, from the color of his hair. These epithets, to be sure, still occur in Ireland, but far less frequently now than in the times of which we write, when Irish was almost the vernacular language of the country. It was for a reason similar to those just alleged, that John O'Rorke was known as Lamh Laudher O'Rorke; he, as well as his forefathers for two or three generations, having been remarkable for prodigious bodily strength and courage. The evening was far advanced as O'Rorke bent his steps to the orchard. The pale, but cloudless sun hung over the western hills, and sun upon the quiet gray fields that kind of tranquil radiance which, in the opening of summer, causes many a silent impulse of delight to steal into the heart. Lamh Laudher felt this; his step was slow, like that of a man who, without being capable of tracing those sources of enjoyment which the spirit absorbs from the beauties of external nature, has yet enough of uneducated taste and feeling within him, to partake of the varied feast which she presents.

As he sauntered thus leisurely along he was met by a woman rather advanced in years, but still unusually stout and muscular, considering her age. She was habited in a red woollen petticoat that reached but a short distance below the knee, leaving visible two stout legs, from which dangled a pair of red garters that bound up her coarse blue hose. Her gown of blue worsted was pinned up, for it did not meet around her person, though it sat closely about her neck. Her grizzly red hair, turned up in front, was bound by a dowd cap without any border, a circumstance which, in addition to a red kerchief, tied over it, and streaming about nine inches down the back, gave to her tout ensemble a wild and striking expression. A short oaken staff, hooked under the hand, completed the description of her costume. Even on a first glance there appeared to be something repulsive in her features, which had evidently been much exposed to sun and storm. By a closer inspection one might detect upon their hard angular outline, a character of cruelty and intrepidity. Though her large cheek-bones stood widely asunder, yet her gray piercing eyes were very near each other; her nose was short and sadly disfigured by a scar that ran tranversely across it, and her chin, though pointed, was also deficient in length. Altogether, her whole person had something peculiar and marked about it—so much so, indeed, that it was impossible to meet her without feeling she was a female of no ordinary character and habits.

Lamh Laudher had been, as we have said, advancing slowly along the craggy road which led towards the town, when she issued from an adjoining cabin and approached him. The moment he noticed her he stood still, as if to let her pass and uttered one single exclamation of chagrin and anger.

“Ma shaughth milia mollach ort, a calliagh! My seven thousand curses on you for an old hag,” said he, and haying thus given vent to his indignation at her appearance, he began to retrace his steps as if unwilling to meet her.

“The son of your father needn't lay the curse upon us so bitterly all out, Lamh Laudher!” she exclaimed, pacing at the same time with vigorous steps until she overtook him.

The young man looked at her maimed features, and as if struck by some sudden recollection, appeared to feel regret for the hasty malediction he had uttered against her. “Nell M'Collum,” said he, “the word was rash; and the curse did not come from my heart. But, Nell, who is there that doesn't curse you when they meet you? Isn't it well known that to meet you is another name for falling in wid bad luck? For my part I'd go fifty miles about rather than cross you, if I was bent on any business that my heart 'ud be in, or that I cared any thing about.”

“And who brought the bad luck upon me first?” asked the woman. “Wasn't it the husband of the mother that bore you? Wasn't it his hand that disfigured me as you see, when I was widin a week of bein' dacently married? Your father, Lamh Laudher was the man that blasted my name, and made it bitther upon tongue of them that mintions it.”

“And that was because he wouldn't see one wid the blood of Lamh Laudher in his veins married to a woman that he had reason to think—I don't like to my it, Nelly—but you know it is said that there was darkness, and guilt, too, about the disappearin' of your child. You never cleared that up, but swore revenge night and day against my father, for only preventin' you from bein' the ruination of his cousin. Many a time, too, since that, has asked you in my own hearing what became of the boy.”

The old woman stopped like one who had unexpectedly trod with bare foot upon something sharp enough to pierce the flesh to the bone, and even to grate against it. There was a strong, nay, a fearful force of anguish visible in what she felt. Her brows were wildly depressed from their natural position, her face became pale, her eyes glared upon O'Rorke as if he had planted a poisoned arrow in her breast, she seized him by the arm with a hard pinching grip, and looked for two or three minutes in his face, with an appearance of distraction. O'Rorke, who never feared man, shrunk from her touch, and shuddered under the influence of what had been, scarcely without an exception, called the “bad look.” The crone held him tight, however, and there they stood, with their eyes fixed upon each other. From the gaze of intense anguish, the countenance of Nell M'Collum began to change gradually to one of unmingled exultation; her brows were raised to their proper curves, her color returned, the eye corruscated with a rapid and quivering sense of delight, the muscles of the mouth played for a little, as if she strove to suppress a laugh. At length O'Rorke heard a low gurgling sound proceed from her chest; it increased; she pressed his arm more tightly, and in a loud burst of ferocious mirth, which she immediately subdued into a condensed shriek that breathed the very luxury of revenge, she said—

“Lamh Laudher Oge, listen—ax the father of you, when you see him, what has become of his own child—of the first that ever God sent him; an' listen again—when he tells me what has become of mine, I'll tell him what has become of his, Now go to Ellen—but before you go, let me cuggher in your ear that I'll blast you both. I'll make the Lamh Laudhers, Lamh Lhugs. I'll make the strong arm the weak arm afore I've done wid 'em.”

She struck the point of her stick against the pavement, until the iron ferrule with which it was bound dashed the fire from the stones, after which she passed on, muttering threats and imprecations as she left him.

O'Rorke stood and looked after her with sensations of fear and astonishment. The age was superstitious, and encouraged a belief in the influence of powers distinct from human agency. Every part of Ireland was filled at this time with characters, both male and female, precisely similar to old Nell M'Collum.. The darkness in which this woman walked, according to the opinions of a people but slightly advanced in knowledge and civilization, has been but feebly described to the reader. To meet her, was considered an omen of the most unhappy kind; a circumstance which occasioned the imprecation of Lamh Laudher. She was reported to have maintained an intercourse with the fairies, to be capable of communicating the blight of an evil eye, and to have carried on a traffic which is said to have been rather prevalent in Ireland at the time we speak of—namely, that of kidnapping. The speculations with reference to her object in perpetrating the crimes were strongly calculated to exhibit the degraded state of the people at that period. Some said that she disposed of the children to a certain class of persons in the metropolis, who subsequently sent them to the colonies, when grown, at an enormous profit. Others maintained that she never carried them to Dublin at all, but insisted that, having been herself connected with the fairies, she possessed the power of erasing, by some secret charm, the influence of baptismal protection, and that she consequently acted as agent for the “gentry” to whom she transferred them. Even to this day it is the opinion in Ireland, that the “good people” themselves cannot take away a child, except through the instrumentality of some mortal residing with them, who has been baptized; and it is also believed that no baptism can secure children from them, except that in which the priest has been desired to baptize them with an especial view to their protection against fairy power.

Such was the character which this woman bore; whether unjustly or not, matters little. For the present it is sufficient to say, that after having passed on, leaving Lamh Laudher to proceed in the direction he had originally intended, she bent her steps towards the head inn of the town. Her presence here produced some cautious and timid mirth of which they took care she should not be cognizant. The servants greeted her with an outward show of cordiality, which the unhappy creature easily distinguished from the warm kindness evinced to vagrants whose history had not been connected with evil suspicion and mystery. She accordingly tempered her manner and deportment towards them with consummate skill. Her replies to their inquiries for news were given with an appearance of good humor; but beneath the familiarity of her dialogue there lay an ambiguous meaning and a cutting sarcasm, both of which were tinged with a prophetic spirit, capable, from its equivocal drift, of being applied to each individual whom she addressed. Owing to her unsettled life, and her habit of passing from place to place, she was well acquainted with local history. There lived scarcely a family within a very wide circle about her, of whom she did not know every thing that could possibly be known; a fact of which she judiciously availed herself by allusions in general conversations that were understood only by those whom they concerned. These mysterious hints, oracularly thrown out, gained her the reputation of knowing more than mere human agency could acquire, and of course she was openly conciliated and secretly hated.

Her conversation with the menials of the inn was very short and decisive.

“Sheemus,” said she to the person who acted in the capacity of waiter, “where's Meehaul Neil?”

“Troth, Nell, dacent woman,” replied the other, “myself can't exactly say that. I'll be bound he's on the Esker, looking afther the sheep, poor crathurs, durin' Andy Connor's illness in the small-pock. Poor Andy's very ill, Nell, an' if God hasn't sed it, not expected; glory be to his name!”

“Is Andy ill?” inquired Nell; “and how long?”

“Bedad, going on ten days.”

“Well,” said the woman, “I knew nothin' about that; but I want to see Meehaul Neil, and I know he's in the house.”

“Faix he's not, Nelly, an' you know I wouldn't tell you a lie about it.”

“Did you get the linen that was stolen from your masther?” inquired Nell significantly, turning at the same time a piercing glance on the waiter; “an' tell me,” she added, “how is Sally Lavery, and where is she?”

“It wasn't got,” he replied, in a kind of stammer; “an' as to Sally, the nerra one o' me knows any thing about her, since she left this.”

“Sheemus,” replied Nell, “you know that Meehaul Neil is in the house; but I'll give you two choices, either to bring me to the speech of him, or else I'll give your masther the name of the thief that stole his linen; ay! the name of the thief that resaved it. I name nobody at present; an' for that matther, I know nothin'. Can't all the world tell you that Nell M'Cullum knows nothin'!”

“Ghe dhevin, Nelly,” said the waiter, “maybe Meehaul is in the house unknownst to me. I'll try, any how, an' if he's to the fore, it won't be my fault or he'll see you.”

Nell, while the waiter went to inform Meehaul, took two ribbons out of her pocket, one white and the other black, both of which she folded into what would appear to a bystander to be a simple kind of knot. When the innkeeper's son and the waiter returned to the hall, the former asked her what the nature of her business with him might be. To this she made no reply, except by uttering the word husht! and pulling the ends, first of the white ribbon, and afterwards of the black. The knot of the first slipped easily from the complication, but that of the black one, after gliding along from its respective ends, became hard and tight in the middle.

“Tha sha marrho! life passes and death stays,” she exclaimed. “Andy Connor's dead, Meehaul Neil; an' you may tell your father that he must get some one else to look afther his sheep. Ay! he's dead!—But that's past. Meehaul, folly me; it's you I want, an' there's no time to be lost.”

She passed out as she spoke, leaving the waiter in a state of wonder at the extent of her knowledge, and of the awful means by which, in his opinion, she must have acquired it.

Meehaul, without uttering a syllable, immediately walked after her. The pace at which she went was rapid and energetic, betokening a degree of agitation and interest on her part, for which he could not account. As she had no object in bringing him far from the house, she availed herself of the first retired spot that presented itself, in order to disclose the purport of her visit. “Meehaul Neil,” said she, “we're now upon the Common, where no ear can hear what passes between us. I ax have you spirit to keep your sister Ellen from shame and sorrow?” The young man started, and became strongly excited at such a serious prelude to what she was about to utter.

“Millia diououl! woman, why do you talk about shame or disgrace comin' upon any sister of mine?” What villain dare injure her that regards his life? My sisther! Ellen Neil! No, no! the man that 'ud only think of that, I'd give this right hand a dip to the wrist in the best blood of his heart.”

“Ay, ay! it's fine spakin': but you don't know the hand you talk of. It's one that you had better avoid than meet. It's the strong hand, an' the dangerous one when vexed. You know Lamh Laudher Oge?”

Meelmul started again, and the crone could perceive by his manner that the nature of the communication she was about to make had been already known to him, though not, she was confident, in so dark and diabolical a shape as that in which she determined to put it.

“Lamh Laudher Oge!” he exclaimed; “surely you don't mane to say that he has any bad design upon Ellen! It's not long since I gave him a caution to drop her, an' to look out for a girl fittin' for his station. Ellen herself knows what he'll get, if we ever catch him spakin' to her again. The day will never come that his faction and ours can be friends.”

“You did do that, Meehaul,” replied Nell, “an' I know it; but what 'ud you think if he was so cut to the heart by your turnin' round upon his poverty, that he swore an oath to them that I could name, bindin' himself to bring your sister to a state of shame, in order to punish you for your words? That 'ud be great glory over a faction that they hate.”

“Tut, woman, he daren't swear such an oath; or, if he swore it fifty times over on his bare knees, he'd ate the stones off o' the pavement afore he'd dare to act upon it. In the first place, I'd prepare him for his coffin, if he did; an' in the next, do you think so inanely of Ellen, as to believe that she would bring disgrace an' sorrow upon herself and her family? No, no, Nell; the old dioul's in you, or you're beside yourself, to think of such a story. I've warned her against him, and so did we all; an' I'm sartin' this minute, that she'd not go a single foot to change words with him, unknownst to her friends.”

The old woman's face changed from the expression of anxiety and importance that it bore, to one of coarse glee, under which, to those who had penetration sufficient to detect it, lurked a spirit of hardened and reckless ferocity.

“Well, well,” she replied, “sure I'm proud to hear what you tell me. How is poor Nanse M'Collum doin' wid yez? for I hadn't time to see her a while agone. I hope she'll never be ashamed or afraid of her aunt, any how. I may say, I'm all that's left to the good of her name, poor girshah.”

“What 'ud ail her?” replied Meehaul; “as long a' she's honest an' behaves herself, there's no fear of her. Had you nothing elsa to say to me, Nell?”

The same tumultuous expression of glee and malignity again lit up the features of the old woman, as she looked at him, and replied, with something like contemptuous hesitation, “Why, I don't know that. If you had more sharpness or sinse I might say—Meehaul Neil,” she added, elevating her voice, “what do you think I could say, this sacred moment! Your sister! Why she's a good girl!—true enough that: but how long she may be so's another affair. Afeard! Be the ground we stand on, man dear, if you an' all belongin' to you, had eyes in your heads for every day in the year, you couldn't keep her from young Lamh Laudher. Did you hear anything?”

“I'd not believe a word of it,” said Meehaul calmly, and he turned to depart.

“I tell you it's as true as the sun to the dial,” replied Nell; “and I tell you more, he's wid her this minnit behind your father's orchard! Ay! an' if you wish you may see them together wid your own eyes, an' sure if you don't b'lieve me, you'll b'lieve them. But, Meehaul, take care of him; for he has his fire-arms; if you meet him don't go empty-handed, and I'd advise you to have the first shot.”

“Behind the orchard,” said Meehaul, astonished; “where there?”

“Ay, behind the orchard, where they often war afore. Where there? Why, if you want to know that, sittin' on one of the ledges in the Grassy Quarry. That's their sate whenever they meet; an' a snug one it is for them that don't like their neighbors' eyes to be upon them. Go now an' satisfy yourself, but watch them at a distance, an', as you expect to save your sister, don't breathe the name of Nell M'Collum to a livin' mortal.”

Meehaul Neil's cheek flushed with deep resentment on hearing this disagreeable intelligence. For upwards of a century before there had subsisted a deadly feud between the Neils and Lamh Laudhers, without either party being able exactly to discover the original fact from which their enmity proceeded. This, however, in Ireland, makes little difference. It is quite sufficient to know that they meet and fight upon every possible opportunity, as hostile factions ought to do, without troubling themselves about the idle nonsense of inquiring why they hate and maltreat each other. For this reason alone, Meehaul Neil was bitterly opposed to the most distant notion of a marriage between his sister and young Lamh Laudher. There were other motives also which weighed, with nearly equal force, in the consideration of this subject. His sister Ellen was by far the most beautiful girl of her station in the whole country,—and many offers, highly advantageous, and far above what she otherwise could have expected, had been made to her. On the other hand, Lamh Laudher Oge was poor, and by no means qualified in point of worldly circumstances to propose for her, even were hereditary enmity out of the question. All things considered, the brother and friends of Ellen would rather have seen her laid in her grave, than allied to a comparatively poor young man, and their bitterest enemy.

Meehaul had but little doubt as to the truth of what Nell M'Collum told him. There was a saucy and malignant confidence in her manner, which, although it impressed him with a sense of her earnestness, left, nevertheless, an indefinite feeling of dislike against her on his mind. He knew that her motive for disclosure was not one of kindness or regard for him or for his family. Nell M'Collum had often declared that “the wide earth did not carry a bein' she liked or loved, but one—not even excepting herself, that she hated most of all.” This however was not necessary to prove that she acted rather from the gratification of some secret malice, than from the principle of benevolence. The venomous leer of her eye, therefore, and an accurate knowledge of her character, induced him to connect some apprehension of approaching evil with the unpleasant information she had just given him.

“Well,” said Meehaul, “if what you say is true, I'll make it a black business to Lamh Laudher. I'll go directly and keep my eye on them; an' I'll have my fire-arms, Nell; an' by the life that's in me, he'll taste them if he provokes me; an Ellen knows that.” Having thus spoken he left her.

The old woman stood and looked after him with a fiendish complacency.

“A black business, will you?” she exclaimed, repeating his words in a soliloquy;—“do so—an' may all that's black assist you in it! Dher Chiernah, I'll do it or lose a fall—I'll make the Lamh Laudhers the Lamh Lhugs afore I've done wid 'em. I've put a thorn in their side this many a year, that'll never come out; I'll now put one in their marrow, an' let them see how they'll bear that. I've left one empty chair at their hearth, an' it 'll go hard wid me but I'll lave another.”

Having thus expressed her hatred against a family to whom she attributed the calamities that had separated her from society, and marked her as a being to be avoided and detested, she also departed from the Common, striking her stick with peculiar bitterness into the ground as she went along.

In the mean time young Lamh Laudher felt little suspicion that the stolen interview between him and Ellen Neil was known. The incident, however, which occurred to him on his way to keep the assignation, produced in his mind a vague apprehension which he could not shake off. To meet a red-haired woman, when going on any business of importance, was considered at all times a bad omen, as it is in the country parts of Ireland unto this day; but to meet a female familiar with forbidden powers, as Nell M'Collum was supposed to be, never failed to produce fear and misgiving in those who met her. Mere physical courage was no bar against the influence of such superstitions; many a man was a slave to them who never knew fear of a human or tangible enemy. They constituted an important part of the popular belief! for the history of ghosts and fairies, and omens, was, in general, the only kind of lore in which the people were educated; thanks to the sapient traditions of their forefathers.

When Nell passed away from Lamh Laudher, who would fain have flattered himself that by turning back on the way, until she passed him, he had avoided meeting her, he once more sought the place of appointment, at the same slow pace as before. On arriving behind the orchard, he found, as the progress of the evening told him, that he had anticipated the hour at which it had been agreed to meet. He accordingly descended the Grassy Quarry, and sat on a mossy ledge of rock, over which the brow of a little precipice jutted in such a manner as to render those who sat beneath, visible only from a particular point. Here he had scarcely seated himself when the tread of a foot was heard, and in a few minutes Nanse M'Collum stood beside him.

“Why, thin, bad cess to you, Lamh Laudher,” she exclaimed, “but it's a purty chase I had afther you.”

“Afther me, Nanse? and what's the commission, cush gastha (lightfoot)?”

“The sorra any thing, at all, at all, only to see if you war here. Miss Ellen sent me to tell you that she's afeard she can't come this evenin', unknownst to them.”

“An' am I not to wait, Nanse?”

“Why, she says she—will come, for all that, if she can; but she bid me take your stick from you, for a rason she has, that she'll tell yourself when she sees you.”

“Take my stick! Why Nanse, ma colleen baun, what can she want with my stick? Is the darlin' girl goin' to bate any body?”

“Bad cess to the know I know, Lamh Laudher, barrin' it be to lay on yourself for stalin' her heart from her. Why thin, the month's mether o' honey to you, soon an' sudden, how did you come round her at all?”

“No matter about that, Nanse; but the family's bitther against me?—eh?”

“Oh, thin, in trogs, it's ill their common to hate you as they do; but thin, you see, this faction-work will keep yees asundher for ever. Now gi' me your stick, an' wait, any way, till you see whether she comes or not.”

“Is it by Ellen's ordhers you take it, Nanse?”

“To be sure—who else's? but the divil a one o' me knows what she means by it, any how—only that I daren't go back widout it.”

“Take it, Nanse; she knows I wouldn't refuse her my heart's blood, let alone a bit of a kippeen.”

“A bit of a kippeen! Faix, this is a quare kippeen! Why, it would fell a bullock.”

“When you see her, Nanse, tell her to make haste, an' for God's sake not to disappoint me. I can't rest well the day I don't meet her.”

“Maybe other people's as bad, for that matter; so good night, an' the mether o' honey to you, soon an' sudden! Faix, if any body stand in my way now, they'll feel the weight of this, any how.”

After uttering the last words, she brandished the cudgel and disappeared.

Lamh Laudher felt considerably puzzled to know what object Ellen could have had in sending the servant maid for his staff. Of one thing, however, he was certain, that her motive must have had regard to his own safety; but how, or in what manner, he could not conjecture. It is certainly true some misgivings shot lightly across his imagination, on reflecting that he had parted with the very weapon which he usually brought with him to repel the violence of Ellen's friends, should he be detected in an interview with her. He remembered, too, that he had met unlucky Nell M'Collum, and that the person who deprived him of his principal means of defence was her niece. He had little time, however, to think upon the subject, for in a few minutes after Nanse's departure, he recognized the light quick step of her whom he expected.

The figure of Ellen Neil was tall, and her motions full of untaught elegance and natural grace. Her countenance was a fine oval; her features, though not strictly symmetrical, were replete with animation, and her eyes sparkled with a brilliancy indicative of a warm heart and a quick apprehension. Flaxen hair, long and luxuriant, decided, even at a distant glance, the loveliness of her skin, than which the unsunned snow could not be whiter. If you add to this a delightful temper, buoyant spirits, and extreme candor, her character, in its strongest points, is before you.

On reaching the bottom of the Grassy Quarry, as it was called, she peered under the little beetling cliff that overhung the well-known ledge on which Lamh Laudher sat.

“I declare, John,” said she, on seeing him, “I thought at first you weren't here.”

“Did you ever know me to be late!—” said John, taking her by the hand, and placing her beside him; “and what would you a' done, Ellen, if I hadn't been here?”

“Why, run home as if the life was lavin' me, for fear of seein' something.”

“You needn't be afeard, Ellen, dear; nothing could harm you, at all events. However, puttin' that aside, have you any betther tidin's than you had when we met last?”

“I wish to heaven I had, John! but indeed I have far worse; ay, a thousand times worse. They have all joined against me, an' I'm not to see or speak to you at all.”

“That's hard,” replied Lamh Laudher, drawing his breath tightly; “but I know where it comes from. I think your father might be softened a little, ay, a great deal, if it wasn't for your brother Meehaul.”

“Indeed, Lamh Laudher, you're wrong in that; my father's as bitther against you as he is. It was only on Tuesday evenin' last that they told me, one an' all they would rather see me a corpse than your wife. Indeed an' deed, John, I doubt it never can be.”

“There,” replied John, “I see plain enough that they'll gain you over at last. That will be the end of it: but if you choose to break the vows and promises that passed between us, you may do so.”

“Oh! Lamh Laudher,” said Ellen, affected at the imputation contained in his last observation; “don't you treat me with such suspicion. I suffer enough for your sake, as it is. For nearly two years, a day has hardly passed that my family hasn't wrung the burnin' tears from my eyes on your account. Haven't I refused matches that any young woman in my station of life ought to be I proud to accept?”

“You did, Ellen, you did; but still I know how hard it is for you to hould out against the persecution you suffer at home. No, no, Ellen dear, I never doubted you for one minute. All I wondher at is, that such a girl as you ever could think of one so humble as I am, compared to what you'd have a right to expect an' could get.”

“Well, but if I'm willin' to prefer you, John?” said Ellen, with a smile.

“One thing I know, Ellen,” he replied, “an' that is, that I'm far from bein' worthy of you; an' I ought, if I had a high enough spirit, to try to turn you against me, if it was only that you might marry a man that 'ud have it in his power to make you happier than ever I'll be able to do; any way, than ever it's likely I'll be able to do.”

“I don't think, John, that ever money or the wealth of the world made a man an' wife love one another yet, if they didn't do it before; but it has often put their hearts against one another.”

“I agree wid you in that, Ellen; but you don't know how my heart sinks when I think of your an' my own poverty. My poor father, since the strange disappearance of little Alice, never was able to raise his head; and indeed my mother was worse. If the child had died, an' that we knew she slept with ourselves, it would be a comfort. But not to know what became of her—whether she was drowned or kidnapped—that was what crushed their hearts. I must say that since I grew up, we're improvin'; an' I hope, God willin', now that my father laves the management of the farm to myself, we'll still improve more an' more. I hope it for their sakes, but—more, if possible, for yours. I don't know what I wouldn't do to make you happy, Ellen. If my life could do it, I think I could lay it down to show the love I bear you. I could take to the highway and rob for your sake, if I thought it would bring me means to make you happy.”

Ellen was touched by his sincerity, as well as by the tone of manly sorrow with which he spoke. His last words, however, startled her, when she considered the vehement manner in which he uttered them.

“John,” said she, alarmed, “never, while you have life, let me hear a word of that kind out of your lips. No—never, for the sake of heaven above us, breathe it, or think of it. But, I'll tell you something, an' you must hear it, an' bear it too, with patience.”

“What is it, Ellen! If it's fair an' manly, I'll be guided by your advice.”

“Meehaul has threatened to—to—I mane to say, that you musn't have any quarrel with him, if he meets you or provokes you. Will you promise this?”

“Meenaul has threatened to strike me, has he? An' I, a Lamh Laudher, am to take a blow from a Neil, an' to thank him, I suppose, for givin' it.”

Ellen rose up and stood before him.

“Lamh Laudher,” said she, “I must now try your love for me in earnest. A lie I cannot tell no more than I can cover the truth. My brother has threatened to strike you, an' as I said afore, you must bear it for his sister's sake.”

“No, dher Chiernah, never. That, Ellen, is goin' beyant what I'm able to bear. Ask me to cut off my right hand for your sake, an' I'll do it; ask my life, an' I'll give it: but to ask a Lamh Laudher to bear a blow from a Neil—never. What! how could I rise my face afther such a disgrace? How could I keep the country wid a Neil's blow, like the stamp of a thief upon my forehead, an' me the first of my own faction, as your brother is of his. No—never!”

“An' you say you love me, John?”

“Betther than ever man loved woman.”

“No, man—you don't,” she replied; “if you did, you'd give up something for me. You'd bear that for my sake, an' not think it much. I'm beginin' to believe, Lamh Laudher, that if I was a poor portionless girl, it wouldn't be hard to put me out of your thoughts. If it was only for my own sake you loved me, you'd not refuse me the first request I ever made to you; when you know, too, that if I didn't think more of you than I ought, I'd never make it.”

“Ellen, would you disgrace me? Would you wish me to bear the name of a coward? Would you want my father to turn me out of the house? Would you want my own faction to put their feet upon me, an' drive me from among them?”

“John,” she replied, bursting into tears, “I do know that it's a sore obligation to lay upon you, when everything's taken into account; but if you wouldn't do this for me, who would you do it for? Before heaven, John, I dread a meetin' between you an' my brother, afther what he tould me; an' the only way of preventin' danger is for you not to strike him. Oh, little you know what I have suffered these two days for both your sakes! Lamh Laudher Oge, I doubt it would be well for me if I had never seen your face.”

“Anything undher heaven but what you want me to do, Ellen.”

“Oh! don't refuse me this, John. I ask it, as I said, for both your sake, an' for my own sake. Meehaul wouldn't strike an unresistin' man. I won't lave you till you promise; an' if that won't do, I'll go down on my. knees an' ask you for the sake of heaven above, to be guided by me in this.”

“Ellen, I'll lave the country to avoid him, if that'll plase you.”

“No—no—no, John: that doesn't plase me. Is it to lave your father an' family, an' you the staff of their support? Oh, John, give me your promise. Here on my two knees I ask it from you, for my own, for your own, and for the sake of God above us! I know Meehaul. If he got a blow from you on my account, he'd never forgive it to either you or me.”

She joined her hands in supplication to him as she knelt, and the tears chased each other like rain down her cheeks. The solemnity with which she insisted on gaining her point staggered Lamh Laudher not a little.

“There must be something undher this,” he replied, “that makes you set your heart on it so much. Ellen, tell me the truth; what is it?”

“If I loved you less, John, an' my brother too, I wouldn't care so much about it. Remember that I'm a woman, an' on my knees before you. A blow from you would make him take your life or mine, sooner than that I should become your wife. You ought to know his temper.”

“You know, Ellen, I can't at heart refuse you any thing. I will not strike your brother.”

“You promise, before God, that no provocation will make you strike him.”

“That's hard, Ellen; but—well, I do; before God, I won't—an' it's for your sake I say it. Now, get up, dear, get up. You have got me to do what no mortal livin' could bring me to but yourself. I suppose that's what made you send Nanse M'Collum for my staff?”

“Nancy M'Collum! When?”

“Why, a while ago. She tould me a quare enough story, or rather no story at all, only that you couldn't come, an' you could come, an' I was to give up my staff to her by your ordhers.”

“She tould you false, John. I know nothing about what you say.”

“Well, Ellen,” replied Lamh Laudher, with a firm seriousness of manner, “you have brought me into danger. I doubt, without knowin' it. For my own part, I don't care so much. Her unlucky aunt met me comin' here this evenin', and threatened both our family and yours. I know she would sink us into the earth if she could. Either she or your brother is at the bottom of this business, whatever it is. Your brother I don't fear; but she is to be dreaded, if, all's true that's said about her.”

“No, John—she surely couldn't have the heart to harm, you an' me. Oh, but I'm light now, since you did what I wanted you. No harm can come between you and Meehaul; for I often heard him say, when speakin' about his faction fights, that no one but a coward would, strike an unresistin' man. Now come and see me pass the Pedlar's Cairn, an' remember that you'll thank me for what I made you do this night. Come quickly—I'll be missed.”

They then passed on by a circuitous and retired path that led round the orchard, until he had conducted her in safety beyond the Pedlar's Cairn, which was so called from a heap of stones that had been loosely piled together, to mark the spot as the scene of a murder, whose history, thus perpetuated by the custom of every passenger casting a stone upon the place, constituted one of the local traditions of the neighborhood.

After a tender good-night, given in a truly poetical manner under the breaking light of a May moon, he found it necessary to retrace his steps by a path which wound round the orchard, and terminated in the public entrance to the town. Along this suburban street he had advanced but a short way, when he found himself overtaken and arrested by his bitter and determined foe, Meehaul Neil. The connection betwixt the promise that Ellen had extorted from him and this rencounter with her brother flashed upon him forcibly: he resolved, however, to be guided by her wishes, and with this purpose on his part, the following dialogue took place between the heads of the rival factions. When we say, however, that Lamh Laudher was the head of his party, we beg to be understood as alluding only to his personal courage and prowess; for there were in it men of far greater wealth and of higher respectability, so far as mere wealth could confer the latter.

“Lamh Laudher,” said Meehaul, “whenever a Neil spakes to you, you may know it's hot in friendship.”

“I know that, Meehaul Neil, without hearin' it from you. Spake, what have you to say?”

“There was a time,” observed the other, “when you and I were enemies only because our cleaveens were enemies but now there is, an' you know it, a blacker hatred between us.”

“I would rather there was not, Meehaul; for my own part, I have no ill-will against either you or yours, all you know that; so when you talk of hatred, spake only for yourself.”

“Don't be mane, man,” said Neil; “don't make them that hates you despise you into the bargain.”

Lamh Laudher turned towards him fiercely, and his eye gleamed with passion; but he immediately recollected himself, and simply said—

“What is your business with me this night, Meehaul Neil?”

“You'll know that soon enough—sooner, maybe, than you wish. I now ask you to tell me, if you are an honest man, where you have been?”

“I am as honest, Meehaul, as any man that ever carried the name of Neil upon him, an' yet I won't tell you that, till you show me what right you have to ask me.”

“I b'lieve you forget that I'm Ellen Neil's brother: now, Lamh Laudher, as her brother, I choose to insist on your answering me.”

“Is it by her wish?”

“Suppose I say it is.”

“Ay! but I won't suppose that, till you lay your right hand on your heart, and declare as an honest man, that—tut, man—this is nonsense. Meehaul, go home—I would rather there was friendship between us.”

“You were with Ellen, this night in the! Grassy Quarry.”

“Are you sure of that?”

“I saw you both—I watched you both; you left her beyond the Pedlar's Cairn, an' you're now on your way home.”

“An' the more mane you, Meehaul, to become a spy upon a girl that you know is as pure as the light from heaven. You ought to blush for doubtin' sich a sister, or thinkin' it your duty to watch her as you do.”

“Lamh Laudher, you say that you'd rather there was no ill-will between us.”

“I say that, God knows, from my heart out.”

“Then there's one way that it may be so. Give up Ellen; you'll find it for your own interest to do so.”

“Show me that, Meehaul.”

“Give her up, I say, an' then I may tell you.”

“Meehaul, good-night. Go home.”

They had now entered the principal street of the town, and as they proceeded in what appeared to be an earnest, perhaps a friendly conversation, many of their respective acquaintances, who lounged in the moonlight about their doors, were not a little surprised at seeing them in close conference. When Lamh Laudher wished him good night, he had reached an off street which led towards his father's house, a circumstance at which he rejoiced, as it would have been the means, he hoped, of terminating a dialogue that was irksome to both parties. He found himself, however, rather unexpectedly and rudely arrested by his companion.

“We can't part, Lamh Laudher,” said Meehaul seizing him by the collar, “'till this business is settled—I mane till you promise to give my sister up.”

“Then we must stand here, Meehaul, as long as we live—an' I surely won't do that.”

“You must give her up, man.”

“Must! Is it must from a Neil to a Lamh Laudher? You forgot yourself, Meehaul: you are rich now, an' I'm poor now; but any old friend can tell you the differ between your grandfather an' mine. Must, indeed!”

“Ay; must is the word, I say; an' I tell you that from this spot you won't go till you swear it, or this stick—an' it's a good one—will bring you to submission.”

“I have no stick, an' I suppose I may thank you for that.”

“What do you mane?” said Neil; “but no matter—I don't want it. There—to the divil with it;” and as he spoke he threw it over the roof of the adjoining house.

“Now give up my sister or take the consequence.”

“Meehaul, go home, I say. You know I don't fear any single man that ever breathed; but, above all men on this earth, I wish to avoid a quarrel with you. Do you think, in the mean time, that even if I didn't care a straw for your sister, I could be mane enough to let myself be bullied out of her by you, or any of your faction? Never, Meehaul; so spare your breath, an' go home.”

Several common acquaintances had collected about them, who certainly listened to this angry dialogue between the two faction leaders with great interest. Both were powerful men, young, strong, and muscular. Meehaul, of the two, was taller, his height being above six feet, his strength, courage, and activity, unquestionably very great. Lamh Laudher, however, was as fine a model of physical strength, just proportion, and manly beauty as ever was created; his arms, in particular, were of terrific strength, a physical advantage so peculiar to his family as to occasion the epithet by which it was known. He had scarcely uttered the reply we have I written, when Meehaul, with his whole! strength, aimed a blow at his stomach, which the other so far turned aside, as to bring it I higher up on his chest. He staggered back, after receiving it, about seven or eight yards, but did not fall. His eye literally blazed, and for a moment he seemed disposed to act! under the strong impulse of self-defence. The solemnity of his promise to Ellen, however, recurred to him in time to restrain his uplifted arm. By a strong and sudden effort he endeavored to compose himself, and succeeded. He approached Meehaul, and with as much calmness as he could assume, said—

“Meehaul, I stand before you an' you may strike, but I won't return your blows: I have reasons for it, but I tell you the truth.”

“You won't fight?” said Meehaul, with mingled rage and scorn.

“No,” replied the other, “I won't fight you.”

A murmur of “shame” and “coward” was heard from those who had been drawn together by their quarrel.

“Dher ma chorp,” they exclaimed with astonishment, “but Lamh Laudher's afeard of him!—the garran bane's in him, now that he finds he has met his match.”

“Why, hard fortune to you, Lamh Laudher, will you take a blow from a Neil? Are you goin' to disgrace your name?”

“I won't fight him,” replied he to whom they spoke, and the uncertainty of his manner was taken for want of courage.

“Then,” said Meehaul, “here, before witnesses, I give you the coward, that you may carry the name to the last hour of your life.”

He inflicted, when uttering the words, a blow with his open hand on Lamh Laudher's cheek, after which he desired the spectators to bear witness to what he had done. The whole crowd was mute with astonishment, not a murmur more was heard; but they looked upon the two rival champions, and then upon each other with amazement. The high-minded young man had but one course to pursue. Let the consequence be what it might, he could not think for a moment of compromising the character of Ellen, nor of violating his promise, so solemnly given; with a flushed cheek, therefore, and a brow redder even with shame than indignation, he left the crowd without speaking' a word, for he feared that by indulging in any further recrimination on the subject, his resolution might give way under the impetuous resentment which he curbed in with such difficulty.

Meehaul Neil paused and looked after him, equally struck with surprise and contempt at his apparent want of spirit.

“Well,” he exclaimed to those who stood about him, “by the life within me, if all the parish had sworn that Lamh Laudher Oge was a coward, I'd not a b'lieved them!”

“Faix, Misther Neil, who would, no more, than yourself?” they replied; “devil the likes of it ever we seen! The young fellow that no man could stand afore five minutes!”

“That is,” replied others, “bekase he never met a man that would fight him. You see when he did, how he has turned out. One thing any how is clear enough—after this he can never rise his head while he lives.”

Meehaul now directed his steps homewards, literally stunned by the unexpected cowardice of his enemy. On approaching his father's door, he found Nell M'Collum seated on a stone bench, waiting his arrival. The moment she espied him she sprang to her feet, and with her usual eagerness of manner, caught the breast of his coat, and turning him round towards the moonlight, looked eagerly into his face.

“Well,” she inquired, “did he show his fire-arms? Well? What was done?”

“Somebody has been making a fool of you, Nell,” replied Meehaul; “he had neither fire-arms, nor staff, nor any thing else; an' for my part, I might as well have left mine at home.”

“Well, but, douol, man, what was done? Did you smash him? Did you break his bones?”

“None of that, Nell, but worse; he's disgraced for ever. I struck him, an' he refused to fight me; he hadn't a hand to raise.

“No! Dher Chiernah, he had not; an' he may thank Nell M'Collum for that. I put the weakness over him. But I've not done wid him yet. I'll make that family curse the day they crossed Nell M'Collum, if I should go down for it. Not that I have any ill will to the boy himself, but the father's heart's in him, an' that's the way, Meehaul, I'll punish the man that was the means of lavin' me as I am.”

“Nell, the devil's in your heart,” replied Meehaul, “if ever he was in mortal's. Lave me, woman: I can't bear your revengeful spirit, an' what is more, I don't want you to interfere in this business, good, bad, or indifferent. You bring about harm, Nell; but who has ever known you to do good?”

“Ay! ay!” said the hag, “that's the cuckoo song to Nell; she does harm, but never does good! Well, may my blackest curse wither the man that left Nell to hear that, as the kindest word that's spoke either to her or of her! I don't blame you. Meehaul—I blame nobody but him for it all. Now a word of advice before you go in; don't let on to Ellen that you know of her meetin' him this night;—an' reason good,—if she thinks you're watchin' her, she'll be on her guard—'ay, an' outdo you in spite of your teeth. She's a woman—she's a woman. Good night, an' mark him the next time betther.”

Meehaul himself—had come to the same determination and from the same motive.

The consciousness of Lamh Laudher's public disgrace, and of his incapability to repel it, sank deep into his heart. The blood in his veins became hot and feverish when he reflected upon the scornful and degrading insult he had just borne. Soon after his return home, his father and mother both noticed the singularly deep bursts of indignant feeling with which he appeared to be agitated. For some time they declined making any inquiry as to its cause, but when they saw at length the big scalding tears of shame and rage start from his flashing eyes, they could no longer restrain their concern and curiosity.

“In the name of heaven, John,” said they, “what has happened to put you in such a state as you're in?”

“I can't tell you,” he replied; “if you knew it, you'd blush with burnin' shame—you'd curse me in your heart. For my part, I'd rather be dead fifty times over than livin', after what has happened this night.”

“An' why not tell us, Lamh Laudher?”

“I can't father; I couldn't stand upright afore you and spake it. I'd sink like a guilty man in your presence; an' except you want to drive me distracted, or perjured, don't ask me another question about it. You'll hear it too soon.”

“Well, we must wait,” said the father; “but I'm sure, John, you'd not do anything unbecomin' a man. For my part, I'm not unasy on your account, for except to take an affront from a Neil, there's nothing you would do could shame me.”

This was a' fresh stab to the son's wounded pride, for which he was not prepared. With a stifled groan he leaped to his feet, and rushing from the kitchen, bolted himself up in his bed-room.

His parents, after he had withdrawn, exchanged glances.

“That went home to him,” said the father; “an' as sure as death, the Neils are in it, whatever it is. But by the crass that saved us, if he tuck an affront from any of them, without payin' them home double, he is no son of mine, an' this roof won't cover him another night. Howsomever we'll see in the morn-in', plase God!”

The mother, who was proud of his courage and prowess, scouted with great indignation the idea of her son's tamely putting up with an insult from any of the opposite faction.

“Is it he bear an affront from a Neil! arrah, don't make a fool of yourself, old man! He'd die sooner. I'd stake my life on him.”

The night advanced, and the family had retired to bed; but their son attempted in vain to sleep. A sense of shame overpowered him keenly. He tossed and turned, and groaned, at the contemplation of the disgrace which he knew would be heaped on him the following day. What was to be done? How was he to wipe it off? There was but one method, he believed, of getting his hands once more free; that was to seek Ellen, and gain her permission to retract his oath on that very night. With this purpose he instantly dressed, himself, and quietly unbolting his own door, and that of the kitchen, got another staff, and passed out to seek her father's inn.

The night had now become dark, but mild and agreeable; the repose of man and nature was deep, and save his own tumultuous thoughts every thing breathed an air of peace and rest. At a quick but cautious pace he soon reached the inn, and without much difficulty passed into the garden, from which he hoped to be able to make himself known to Ellen. In this, to his great mortification, he was disappointed; the room in which she slept, being on the third story, presented a window, it is true, to the garden; but how was he to reach it, or hold a dialogue with her, even should she recognize him, without being overheard by some of the family? All this might have occurred to him at home, had he been sufficiently cool for reflection. As it was, the only method of awakening her that he could think of was to throw up several handsful of small pebbles against the window. This he tried without any effect. Pebbles sufficiently large to reach the window would have broken the glass, so that he felt himself compelled to abandon every hope of speaking to her that night. With lingering and reluctant steps he left the garden, and stood for some time before the front of the house, leaning against an upright stone, called the market cross. Here he had not been more than two minutes, when he heard footsteps approaching, and on looking closely through the darkness, he recognized the figure of Nell M'Collum, as it passed directly to the kitchen window. Here the crone stopped, peered in, and with caution gave one of the panes a gentle tap. This was responded to by one much louder from within, and almost immediately the door was softly opened. From thence issued another female figure, evidently that of Nanse M'Collum, her niece. Both passed down the street in a northern direction, and Lamh Laudher, apprehensive that they were on no good errand, took off his shoes, lest his footsteps might be heard, and dogged them as they went along. They spoke little, and that in whispers, until they had got clear of the town, when, feeling less restraint, the following dialogue occurred to them:—

“Isn't it a quare thing, aunt, that she should come back to this place at all?”

“Quare enough, but the husband's comin' too—he's to folly her.”

“He ought to know that he needn't come here, I think.”

“Why, you fool, how do you know that? Sure the town must pay him fifty guineas, if he doesn't get a customer, and that's worth comin' for. She must be near us by this time. Husht! do you hear a car?”

They both paused to listen, but no car was audible.

“I do not,” replied the niece; “but isn't it odd that he lets her carry the money, an' him trates her so badly'?”

“Why would it be odd? Sure, she takes betther care of it, an' puts it farther than he does. His heart's in a farden, the nager.”

“Rody an' the other will soon spare her that trouble, any way,” replied the niece. “Is there no one with her but the carman?”

“Not one—hould you tongue—here's the gate where the same pair was to meet us. Who is this stranger that Rody has picked up? I hope he's the thing.”

“Some red-headed fellow. Rody says he is honest. I'm wondherin', aunt, what 'ud happen if she'd know the place.”

“She can't, girshah—an' what if she does? She may know the place, but will the place know her? Rody's friend says the best way is to do for her; an' I'm afeard of her, to tell you the truth—but we'll settle that when they come. There now is the gate where we'll sit down. Give a cough till we try if they're———whist! here they are!”

The voices of two men now joined the conversation, but in so low a tone, that Lamh Laudher could not distinctly hear its purport.

The road along which they traveled was craggy, and full of ruts, so that a car could be heard in the silence of night at a considerable distance. On each side the ditches were dry and shallow; and a small elder hedge, which extended its branches towards the road, afforded Lamh Laudher the obscurity which he wanted. With stealthy pace he crept over and sat beneath it, determined to witness whatever incident might occur, and to take a part in it, if necessary. He had scarcely seated himself when the car which they expected was heard jolting about half a mile off along the way, and the next moment a consultation took place in tones so low and guarded, that every attempt on his part to catch its purport was unsuccessful. This continued with much earnestness, if not warmth, until the car came within twenty perches of the gate, when Nell exclaimed—

“If you do, you may—but remimber I didn't egg you on, or put it into your hearts, at all evints. Maybe I have a child myself livin'—far from me—an' when I think of him, I feel one touch of nature at my heart in favor of her still. I'm black enough there, as it is.”

“Make your mind asy,” said one of them, “you won't have to answer for her.”

The reply which was given to this could not be heard.

“Well,” rejoined,Nell, “I know that. Her comin' here may not be for my good; but—well, take this shawl, an' let the work be quick. The carman must be sent back with sore bones to keep him quiet.”

The car immediately reached the spot where they sat, and as it passed, the two men rushed from the gate, stopped the horse, and struck the carman to the earth. One of them seized him while down, and pressed his throat, so as to prevent him from shouting. A single faint shriek escaped the female, who was instantly dragged off the car and gagged by the other fellow and Nanse M'Collum.

Lamh Laudher saw there was not a moment to be lost. With the speed of lightning he sprung forward, and with a single blow laid him who struggled with the carman prostrate. To pass then to the aid of the female was only the work of an instant. With equal success he struck down the villain with whom she was struggling. Such was the rapidity of his motions, that he had not yet had time even to speak; nor indeed did he wish at all to be recognized in the transaction. The carman, finding himself freed from his opponent, bounced to his legs, and came to the assistance of his charge, whilst Lamh Laudher, who had just flung Nanse M'Collum into the ditch, returned in time to defend both from a second attack. The contest, however, was a short one. The two ruffians, finding that there was no chance of succeeding, fled across the fields; and our humble hero, on looking for Nanse and her aunt, discovered that they also had disappeared. It is unnecessary to detail the strong terms in which the strangers expressed their gratitude to Lamh Laudher.

“God's grace be upon you, whoever you are, young man!” exclaimed the carman; “for wid His help an' your own good arm, it's my downright opinion that you saved us from bein' both robbed an' murthered.”

“I'm of that opinion myself,” replied Lamh Laudher.

“There is goodness, young man, in the tones of your voice,” observed the female; “we may at least ask the name of the person who has saved our lives?”

“I would rather not have my name mentioned in the business,” he replied; “a woman, or a devil, I think, that I don't wish to cross or provoke, has had a hand in it. I hope you haven't been robbed?” he added.

She assured him, with expressions of deep gratitude, that she had not.

“Well,” said he, “as you have neither of you come to much harm, I would take it as the greatest favor you could do me, if you'd never mention a word about it to any one.”

To this request they agreed with some hesitation. Lamh Laudher accompanied them into the town, and saw them safely in a decent second-rate inn, kept by a man named Luke Connor, after which he returned to his father's house, and without undressing, fell into a disturbed slumber until morning.

It is not to be supposed that the circumstances attending the quarrel between him and Meehaul Neil, on the preceding night, would pass off without a more than ordinary share of public notice. Their relative positions were too well known not to excite an interest corresponding with the characters they had borne, as the leaders of two bitter and powerful factions: but when it became certain that Meehaul Neil had struck Lamh Laudher Oge, and that the latter refused to fight him, it is impossible to describe the sensation which immediately spread through the town and parish. The intelligence was first received by O'Rorke's party with incredulity and scorn. It was impossible that he of the Strong Hand, who had been proverbial for courage, could all at once turn coward, and bear the blow from a Neil! But when it was proved beyond the possibility of doubt or misconception, that he received a blow tamely before many witnesses, under circumstances of the most degrading insult, the rage of his party became incredible. Before ten o'clock the next morning his father's house was crowded with friends and relations, anxious to hear the truth from his own lips, and all, after having heard it, eager to point out to him the only method that remained of wiping away his disgrace, namely, to challenge Meehaul Neil. His father's indignation knew no bounds; but his mother, on discovering the truth, was not without that pride and love which, are ever ready to form an apology for the feelings and errors of an only child.

“You may all talk,” she said; “but if Lamh Laudher Oge didn't strike him, he had good reasons for it. How do you know, an' bad cess to your tongues, all through other, how Ellen Neil would like him after weltin' her brother? Don't ye think she has the spirit of her faction in her as well as another?”

This, however, was not listened to. The father would hear of no apology for his son's cowardice but an instant challenge. Either that or to be driven from his father's roof the only alternatives left him.

“Come out here,” said the old man, for the son had not left his humble bed-room, “an' in presence of them that you have brought to shame and disgrace, take the only plan that s left to you, an' send him a challenge.”

“Father,” said the young man, “I have too much of your own blood in me to be afraid of any man—but for all that, I neither will nor can fight Meehaul Neil.”

“Very well,” said the father, bitterly, “that's enough. Dher Manim, Oonagh, you're a guilty woman; that boy's no son of mine. If he had my blood in him, he couldn't act as he did. Here, you intherloper, the door's open for you; go out of it, an' let me never see the branded face of you while you live.” The groans of the son were audible from his bed-room.

“I will go, father,” he replied, “an' I hope the day will come when you'll all change your opinion of me. I can't, however, stir out till I send a message a mile or so out of town.”

The old man in the mean time, wept as if his son had been dead; his tears, however, were not those of sorrow, but of shame and indignation.

“How can I help it,” he exclaimed, “when I think of the way that the Neils will clap their wings and crow over us! If it was from any other family he tuck it so inanely, I wouldn't care so much; but from them! Oh, Chiernah! it's too bad! Turn out, you villain!”

A charge of deeper disgrace, however, awaited the unhappy young man. The last harsh words of the father had scarcely been uttered, when three constables came in, and inquired if his son were at home.

“He is at home,” said the father, with tears in his eyes, “and I never thought he would bring the blush to my face as he did by his conduct last night.”

“I am sorry,” said the principal of them, “for what has happened, both on your account and his. Do you know this hat?”

“I do know it,” replied the old man; “it belongs to John. Come out here,” said he, “here's Tom Breen wid your hat.”

The son left his room, and it was evident from his appearance that he had not undressed at all during the night. The constables immediately observed these circumstances, which they did not fail to interpret to his disadvantage.

“Here is your hat,” said the man who bore it; “one would think you were travelin' all night, by your looks.”

The son thanked him for his civility, got clean stockings, and after arranging his dress, said to his father—

“I'm now ready to go, father, an' as I can't do what you want me to do, there's nothing for me but to leave the country for a while.”

“He acknowledged it himself,” said the father, turning to Breen; “an' in that case, how could I let the son that shamed me live undher my roof?”

“He's the last young man in the country I stand in,” said Breen, “that any one who knew him would suspect to be guilty of robbery. Upon my soul, Lamh Laudher More, I'm both grieved an' distressed at it. We're come to arrest him,” he added, “for the robbery he committed last night.”

“Robbery!” they exclaimed with one voice.

“Ay,” said the man, “robbery, no less—an' what is more, I'm afraid there's little doubt of his guilt. Why did he lave his hat at the place where the attempt was first made? He must come with us.”

The mother shrieked aloud, and clapped her hands like a distressed woman; the father's brow changed from the flushed hue of indignation, and became pale with apprehension.

“Oh! no, no,” he exclaimed, “John never did that. Some qualm might come over him in the other business, but—no, no—your father knows you're innocent of robbery. Yes, John, my blood is in you, and there you're wronged, my son. I know you too well, in spite of all I've said to you, to believe that, my true-hearted boy.”

He grasped his son's hand as he spoke.

And his mother at the same moment caught him in her arms, whilst both sobbed aloud. A strong sense of innate dignity expanded the brow of young Lamh Laudher. He smiled while his parents wept, although his sympathy in their sorrow brought a tear at the same time to his eye-lids. He declined, however, entering into any explanation, and the father proceeded—

“Yes! I know you are innocent, John; I can swear that you didn't leave this house from nine o'clock last night up to the present minute.”

“Father,” said Lamh Laudher, “don't swear that, for it would not be true, although you think it would. I was out the greater part of last night.”

His father's countenance fell again, as did those of his friends who were present, on hearing what appeared to be almost an admission of his guilt.

“Go,” said the old man, “go; naburs, take him with you. If he's guilty of this, I'll never more look upon his face. John, my heart was crushed before, but you're likely to break it out an' out.”

Lamh Laudher Oge's deportment, on hearing himself charged with robbery, became dogged and sullen. The conversation, together with the sympathy and the doubt it excited among his friends, he treated with silent indignation and scorn. He remembered that on the night before, the strange woman assured him she had not been robbed, and he felt that the charge was exceedingly strange and unaccountable.

“Come,” said he, “the sooner this business is cleared up the better. For my part, I don't know what to make of it, nor do I care much how it goes. I knew since yesterday evening, that bad luck was before me, at all events, an' I suppose it must take its course, an' that I must bear it.”

The father had sat down, and now declined uttering a single word in vindication of his' son. The latter looked towards him, when about to pass out, but the old man waved his hand with sorrowful impatience, and pointed to the door, as intimating a wish that he should forthwith depart from under his roof. Loaded with twofold disgrace, he left his family and his friends, accompanied by the constables, to the profound grief and astonishment of all who knew him.

They then conducted him before a Mr. Brooldeigh, an active magistrate of that day, and a gentleman of mild and humane character.

On reaching Brookleigh Hall, Lamh Laudher found the strange woman, Nell M'Collum, Connor's servant maid, and the carman awaiting his arrival. The magistrate looked keenly at the prisoner, and immediately glanced with an expression of strong disgust at Nell M'Collum. The other female surveyed Lamh Laudher with an interest evidently deep; after which she whispered something to Nell, who frowned and shook her head, as if dissenting from what she had heard. Lamh Laudher, on his part surveyed the features of the female with an earnestness that seemed to absorb all sense of his own disgrace and danger.

“O'Rorke,” said the magistrate, “this is a serious charge against you. I trust you may be able effectually to meet it.”

“I must wait, your worship, till I hear fully what it is first,” replied Lamh Laudher, “afther that I'm not afraid of clearin' myself from it.”

The woman then detailed the circumstances of the robbery, which it appeared took place at the moment her luggage was in the act of being removed to her room, after which she added, rather unexpectedly—“And now your worship, I have plainly stated the facts; but I must, in conscience, add, that although this woman,” turning to Nell M'Collum, “is of opinion that the young man before you has robbed me, yet I cannot think he did.”

“I'll swear, your worship,” said Nell, “that on passin' homewards last night, seein' a car wid people about it, at Luke Connor's door, I stood behind the porch, merely to thry if I knew who they wor. I seen this Lamh Laudher wid a small oak box in his hands, an' I'll give my oath that it was open, an' that he put his hands into it, and tuck something out.”

“Pray, Nell, how did it happen that you yourself were abroad at so unseasonable an hour?” said the magistrate.

“Every one knows that I'm out at quare hours,” replied Nell; “I'm not like others. I know where I ought to be, at all times; but last night, if your worship wishes to hear the truth, I was on my way to Andy Murray's wake, the poor lad that was shepherd to the Neils.”

“And pray, Nell,” said his worship, “how did you form so sudden an acquaintance with this respectable looking woman?”

“I knew her for years,” said Nell; “I've seen her in other parts of the country often.”

“You were more than an hour with her last night—were you not?” said his worship.

“She made me stay wid her,” said Nell, “bekase she was a stranger, an' of coorse was glad to see a face she know, afther the fright she got.”

“All very natural, Nell; but in the mean time, she might easily have chosen a more respectable associate. Have you actually lost the sum of six hundred pounds, my good madam?”

“I have positively lost so much,” replied the woman, “together with the certificate of my marriage.”

“And how did you become acquainted with Nell M'Collum?” he inquired.

The stranger was silent, and blushed deeply at this question; but Nell, with more presence of mind, went over to the magistrate, and whispered something which caused him to start, look keenly at her, and then at the plaintiff.

“I must have this confirmed by herself” he said in reply to Nell's disclosure, “otherwise I shall be much more inclined to consider you the thief than O'Rorke, whose character has been hitherto unimpeachable and above suspicion.”

He then beckoned the woman over to his desk, and after having first inquired if she could write, and being replied to in the affirmative, he placed a slip of paper before her, on which was written—“Is that unhappy woman called Nell M'Collum, your mother?”

“Alas! she is, sir,” replied the female, with a deep expression of sorrow. The magistrate then appeared satisfied. “Now,” said he, addressing O'Rorke, “state, fairly and honestly what you have to say in reply to the charge brought against you.”

“Please your worship,” said the young man, “you hear the woman say that she brings no charge against me; but I can prove on oath, that Nell M'Collum and her niece, Nanse M'Collum, along with two men that I don't know, except that one was called Rody, met at Franklin's gate, with an intention of robing, an' it's my firm belief, of murdering this woman.”

He then detailed with great earnestness the incidents and conversation of the preceding night.

“Sir,” replied Nell, with astonishing promptness, “I can prove by two witnesses, that, no longer ago than last night, he said he would take to the high-road, in ordher to get money to enable him to marry Ellen Neil. Yes, you villain, Nanse M'Collum heard every word that passed between you and her in the grassy quarry; an' Ellen, your worship, can prove it too, if she's sent for.”

This had little effect on the magistrate, who at no time placed any reliance on Nell's assertions; he immediately, however, dispatched a summons for Nanse M'Collum.

The carman then related all that he knew, every word of which strongly corroborated what Lamh Laudher had said. He concluded by declaring it to be his opinion, that the prisoner was innocent, and added, that, according to the best of his belief, the box was not open when he left it in the plaintiff's sleeping-room above stairs.

The magistrate again looked keenly and suspiciously towards Nell. At this stage of the proceedings, O'Rorke's father and mother, accompanied by some of their friends, made their appearance. The old man, however, declined to take any part in the vindication of his son. He stood sullenly silent, with his arms folded and his brows knit, as much in indignation as in sorrow. The grief of the mother was louder, for she wept audibly.

Ere the lapse of many minutes, the constable returned, and stated that Nanse was not be found.

“She has not been at her master's house since morning,” he observed, “and they don't know where she is, or what has become of her.”

The magistrate immediately despatched two of the constables, with strict injunctions! to secure her, if possible.

“In the mean time,” he added, “I will order you, Nell M'Collum, to be strictly confined, until I ascertain whether she can be produced or not. Your haunts may be searched with some hope of success, while you are in durance; but I rather think we might seek for her in vain, if you were at liberty to regulate her motions. I cannot expect,” he added, turning to the stranger, “that you should prosecute one so nearly related to you, even if you had proof, which you have not; but I am almost certain, that she has been someway or other concerned in the robbery. You are a modest, interesting woman, and I regret the loss you have sustained. At present there are no grounds for committing any of the parties charged with the robbery. This unhappy woman I commit only as a vagrant, until her niece is found, after that we shall probably be able to see somewhat farther into this strange affair.”

“Something tells' me, sir,” replied the stranger, “that this young man is as innocent of the robbery as the child unborn. It's not my intention ever to think of prosecuting him. What I have done in the matter was against my own wishes.”

“God in heaven bless you for the words!” exclaimed the parents of O'Rorke, each pressing her hand with delight and gratitude. The woman warmly returned their greetings, but instantly felt her bosom heave with a hysterical oppression under which she sank into a state of insensibility. Lamh Laudher More and his wife were proceeding to bring her towards the door for air, when Nell M'Collum insisted on a prior right to render her that service. “Begone, you servant of the devil,” exclaimed the old man, “your wicked breath is bad about any one else; you won!t lay a hand upon her.”

“Don't let her, for heaven's sake!” said his wife; “her eye will kill the woman!”

“You are not aware,” said the magistrate, “that this woman is her daughter?”

“Whose daughter, please your honor,” said the old man indignantly.

“Nell M'Collum's,” he returned.

“It's as false as hell!” rejoined O'Rorke, “beggin' your honor's pardon for sayin' so. I mean it's false for Nell, if she says it. Nell, sir, never had a daughter, an' she knows that; but she had a son, an' she knows best what became of him.”

Nell, however, resolved not to be deterred from getting-the stranger into her own hands. With astonishing strength and fury she attempted to drag the insensible creature from O'Rorke's grasp; but the magistrate, disgusted at her violence, ordered two of the persons present to hold her down.

At length the woman began to recover.

She sobbed aloud, and a copious flow of tears drenched her cheeks. Nell ordered her to tear herself from O'Rorke and his wife:— “Their hands are bad about you,” she exclaimed, “and their son has robbed you, Mary. Lave them, I say, or it will be worse for you.”

The woman paid her no attention; on the contrary, she laid her head on the bosom of O'Rorke's wife, and wept as if her heart would break.

“God help me!” she exclaimed with a bitter sense of her situation, “I am an unhappy, an' a heart-broken woman! For many a year I have not known what it is to have a friendly breast to weep on.”

She then caught O'Rorke's hand and kissed it affectionately, after which she wept afresh;

“Merciful heaven!” said she'—“oh, how will I ever be able to meet my husband! and such a husband! oh, heavens pity me!”

Both O'Rorke and his wife stood over her in tears. The latter bent her head, kissed the stranger, and pressed her to her bosom. “May God bless you!” said O'Rorke himself solemnly; “trust in Him, for he can see justice done to you when man fails.”

The eyes of Nell glared at the group like those of an enraged tigress: she stamped her feet upon the floor, and struck it repeatedly with her stick, as she was in the habit of doing, when moved by strong and deadly passions.

“You'll suffer for that, Mary,” she exclaimed; “and as for you, Lamh Laudher More, my debt's not paid to you yet. Your son's a robber, an I'll prove it before long; every one knows he's a coward too.”