This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Germany, The Next Republic?

Author: Carl W. Ackerman

Release Date: May 5, 2005 [eBook #15770]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GERMANY, THE NEXT REPUBLIC?***

| The title "GERMANY, THE NEXT REPUBLIC?" is chosen because the author believes this must be the goal, the battlecry, of the United States and her Allies. As long as the Kaiser, his generals and the present leaders are in control of Germany's destinies the world will encounter the same terrorism that it has had to bear during the war. Permanent peace will follow the establishment of a Republic. But the German people will not overthrow the present government until the leaders are defeated and discredited. Today the Reichstag Constitutional committee, headed by Herr Scheidemann, is preparing reforms in the organic law but so far all proposals are mere makeshifts. The world cannot afford to consider peace with Germany until the people rule. The sooner the United States and her Allies tell this to the German people officially the sooner we shall have peace. |

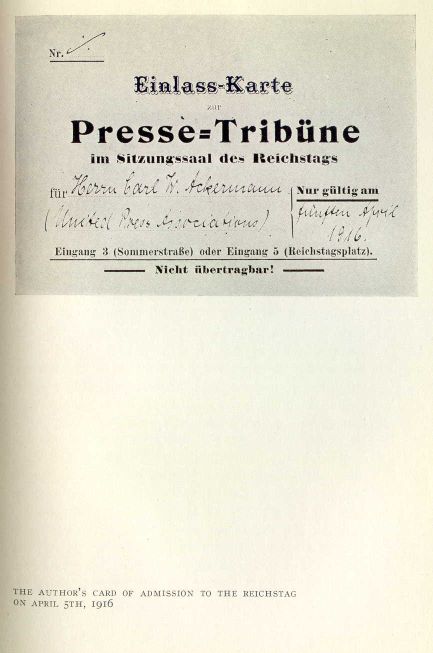

I was at the White House on the 29th of June, 1914, when the newspapers reported the assassination of the Archduke and Archduchess of Austria. In August, when the first declarations of war were received, I was assigned by the United Press Associations to "cover" the belligerent embassies and I met daily the British, French, Belgian, Italian, German, Austro-Hungarian, Turkish and Japanese diplomats. When President Wilson went to New York, to Rome, Georgia, to Philadephia and other cities after the outbreak of the war, I accompanied him as one of the Washington correspondents. On these journeys and in Washington I had an opportunity to observe the President, to study his methods and ideas, and to hear the comment of the European ambassadors.

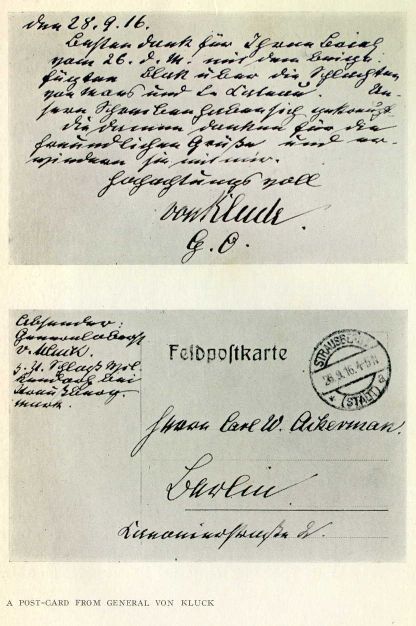

When the von Tirpitz blockade of England was announced in February, 1915, I was asked to go to London where I remained only one month. From March, 1915, until the break in diplomatic relations I was the war correspondent for the United Press within the Central Powers. In Berlin, Vienna and Budapest, I met the highest government officials, leading business men and financiers. I knew Secretaries of State Von Jagow and Zimmermann; General von Kluck, who drove the German first army against Paris in August, 1914; General von Falkenhayn, former Chief of the General Staff; Philip Scheidemann, leader of the Reichstag Socialists; Count Stefan Tisza, Minister President of Hungary and Count Albert Apponyi.

While my headquarters were in Berlin, I made frequent journeys to the front in Belgium, France, Poland, Russia and Roumania. Ten times I was on the battlefields during important military engagements. Verdun, the Somme battlefield, General Brusiloff's offensive against Austria and the invasion of Roumania, I saw almost as well as a soldier.

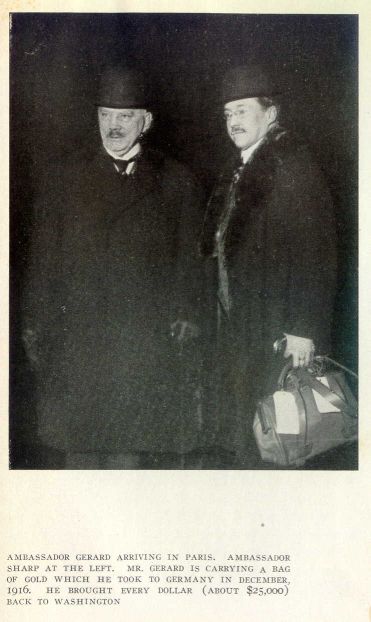

After the sinking of the Lusitania and the beginning of critical relations with the United States I was in constant touch with James W. Gerard, the American Ambassador, and the Foreign Office. I followed closely the effects of American political intervention until February 10th, 1917. Frequent visits to Holland and Denmark gave me the impressions of those countries regarding President Wilson and the United States. En route to Washington with Ambassador Gerard, I met in Berne, Paris and Madrid, officials and people who interpreted the affairs in these countries.

So, from the beginning of the war until today, I have been at the strategic points as our relations with Germany developed and came to a climax. At the beginning of the war I was sympathetic with Germany, but my sympathy changed to disgust as I watched developments in Berlin change the German people from world citizens to narrow-minded, deceitful tools of a ruthless government. I saw Germany outlaw herself. I saw the effects of President Wilson's notes. I saw the anti-American propaganda begin. I saw the Germany of 1915 disappear. I saw the birth of lawless Germany.

In this book I shall try to take the reader from Washington to Berlin and back again, to show the beginning and the end of our diplomatic relations with the German government. I believe that the United States by two years of patience and note-writing, has done more to accomplish the destruction of militarism and to encourage freedom of thought in Germany than the Allies did during nearly three years of fighting. The United States helped the German people think for themselves, but being children in international affairs, the people soon accepted the inspired thinking of the government. Instead of forcing their opinions upon the rulers until results were evident, they chose to follow with blind faith their military gods.

The United States is now at war with Germany because the Imperial Government willed it. The United States is at war to aid the movement for democracy in Germany; to help the German people realize that they must think for themselves. The seeds of democratic thought which Wilson's notes sowed in Germany are growing. If the Imperial Government had not frightened the people into a belief that too much thinking would be dangerous for the Fatherland, the United States would not today be at war with the Kaiser's government. Only one thing now will make the people realize that they must think for themselves if they wish to exist as a nation and as a race. That is a military defeat, a defeat on the battlefields of the Kaiser, von Hindenburg and the Rhine Valley ammunition interests. Only a decisive defeat will shake the public confidence in the nation's leaders. Only a destroyed German army leadership will make the people overthrow the group of men who do Germany's political thinking to-day.

C. W. A.

New York, May, 1917.

|

"Abraham Lincoln said that this Republic could not exist half slave and

half free. Now, with similar clarity, we perceive that the world

cannot exist half German and half free. We have to put an end to the

bloody doctrine of the superior race--to that anarchy which is

expressed in the conviction that German necessity is above all law. We

have to put an end to the German idea of ruthlessness. We have to put

an end to the doctrine that it is right to make every use of power that

is possible, without regard to any restriction of justice, of honour,

of humanity."

New York Tribune, April 7, 1917. |

The Haupttelegraphenamt (the Chief Telegraph Office) in Berlin is the centre of the entire telegraph system of Germany. It is a large, brick building in the Franzoesischestrasse guarded, day and night, by soldiers. The sidewalks outside the building are barricaded. Without a pass no one can enter. Foreign correspondents in Berlin, when they had telegrams to send to their newspapers, frequently took them from the Foreign Office to the Chief Telegraph Office personally in order to speed them on their way to the outside world. The censored despatches were sealed in a Foreign Office envelope. With this credential correspondents were permitted to enter the building and the room where all telegrams are passed by the military authorities.

During my two years' stay in Berlin I went to the telegraph office several times every week. Often I had to wait while the military censor read my despatches. On a large bulletin board in this room, I saw, and often read, documents posted for the information of the telegraph officials. During one of my first waiting periods I read an original document relating to the events at the beginning of the war. This was a typewritten letter signed by the Director of the Post and Telegraph. Because I was always watched by a soldier escort, I could never copy it. But after reading it scores of times I soon memorised everything, including the periods.

This document was as follows:

Office of the Imperial Post & Telegraph

August 2nd, 1914.

Announcement No. 3.

To the Chief Telegraph Office:

From to-day on, the Post and Telegraph communications between Germany on the one hand and:

1. England,

2. France,

3. Russia,

4. Japan,

5. Belgium,

6. Italy,

7. Montenegro,

8. Servia,

9. Portugal;

on the other hand are interrupted because Germany finds herself in a state of war.

(Signed) Director of the Post and Telegraph.

This notice, which was never published, shows that the man who directed the Post and Telegraph Service of the Imperial Government knew on the 2nd of August, 1914, who Germany's enemies would be. Of the eleven enemies of Germany to-day only Roumania and the United States were not included. If the Director of the Post and Telegraph knew what to expect, it is certain that the Imperial Government knew. This announcement shows that Germany expected war with nine different nations, but at the time it was posted on the bulletin board of the Haupttelegraphenamt, neither Italy, Japan, Belgium nor Portugal had declared war. Italy did not declare war until nearly a year and a half afterwards, Portugal nearly two years afterward and Japan not until December, 1914.

This document throws an interesting light upon the preparations Germany made for a world war.

The White, Yellow, Grey and Blue Books, which all of the belligerents published after the beginning of the war, dealt only with the attempts of these nations to prevent the war. None of the nations has as yet published white books to show how it prepared for war, and still, every nation in Europe had been expecting and preparing for a European conflagration. Winston Churchill, when he was First Lord of the Admiralty, stated at the beginning of the war that England's fleet was mobilised. France had contributed millions of francs to fortify the Russian border in Poland, although Germany had made most of the guns. Belgium had what the Kaiser called, "a contemptible little army" but the soldiers knew how to fight when the invaders came. Germany had new 42 cm. guns and a network of railroads which operated like shuttles between the Russian and French and Belgian frontiers. Ever since 1870 Europe had been talking war. Children were brought up and educated into the belief that some day war would come. Most people considered it inevitable, although not every one wanted it.

During the exciting days of August, 1914, I was calling at the belligerent embassies and legations in Washington. Neither M. Jusserand, the French Ambassador, nor Sir Cecil Spring-Rice, the British Ambassador, nor Count von Bernstorff, the Kaiser's representative, were in Washington then. But it was not many weeks until all three had hastened to this country from Europe. Almost the first act of the belligerents was to send their envoys to Washington.

As I met these men I was in a sense an agent of public opinion who called each day to report the opinions of the belligerents to the readers of American newspapers. One day at the British Embassy I was given copies of the White Book and of many other documents which Great Britain had issued to show how she tried to avoid the war. In conversations later with Ambassador von Bernstorff, I was given the German viewpoint.

The thing which impressed me at the time was the desire of these officials to get their opinions before the American people. But why did these ambassadors want the standpoints of their governments understood over here? Why was the United States singled out of all other neutrals? If all the belligerents really wanted to avoid war, why did they not begin twenty years before, to prevent it, instead of, to prepare for it?

All the powers issued their official documents for one primary purpose--to win public opinion. First, it was necessary for each country to convince its own people that their country was being attacked and that their leaders had done everything possible to avoid war. Even in Europe people would not fight without a reason. The German Government told the people that unless the army was mobilised immediately Russia would invade and seize East Prussia. England, France and Belgium explained to their people that Germany was out to conquer the world by way of Belgium and France. But White Books were not circulated alone in Europe; they were sent by the hundreds of thousands into the United States and translated into every known language so that the people of the whole world could read them.

Then the word battles between the Allies and the Central Powers began in the United States. While the soldiers fought on the battlefields of Belgium, France, East Prussia and Poland, an equally bitter struggle was carried on in the United States. In Europe the object was to stop the invaders. In America the goal was public opinion.

It was not until several months after the beginning of the war that Sir Edward Grey and Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg began to discuss what the two countries had done before the war, to avoid it. The only thing either nation could refer to was the 1912 Conference between Lord Haldane and the Chancellor. This was the only real attempt made by the two leading belligerents to come to an understanding to avoid inevitable bloodshed. Discussions of these conferences were soon hushed up in Europe because of the bitterness of the people against each other. The Hymn of Hate had stirred the German people and the Zeppelin raids were beginning to sow the seeds of determination in the hearts of the British. It was too late to talk about why the war was not prevented. So each set of belligerents had to rely upon the official documents at the beginning of the war to show what was done to avoid it.

These White Books were written to win public opinion. But why were the people suddenly taken into the confidence of their governments? Why had the governments of England, France, Germany and Russia not been so frank before 1914? Why had they all been interested in making the people speculate as to what would come, and how it would come about? Why were all the nations encouraging suspicion? Why did they always question the motives, as well as the acts, of each other? Is it possible that the world progressed faster than the governments and that the governments suddenly realised that public opinion was the biggest factor in the world? Each one knew that a war could not be waged without public support and each one knew that the sympathy of the outside world depended more upon public opinion than upon business or military relations.

How America Was Shocked by the War

Previous to July, 1914, the American people had thought very little about a European war. While the war parties and financiers of Europe had been preparing a long time for the conflict, people over here had been thinking about peace. Americans discussed more of the possibilities of international peace and arbitration than war. Europeans lived through nothing except an expectancy of war. Even the people knew who the enemies might be. The German government, as the announcement of the Post and Telegraph Director shows, knew nine of its possible enemies before war had been declared. So it was but natural, when the first reports reached the United States saying that the greatest powers of Europe were engaged in a death struggle, that people were shocked and horrified. And it was but natural for thousands of them to besiege President Wilson with requests for him to offer his services as a mediator.

The war came, too, during the holiday season in Europe. Over 90,000 Americans were in the war zones. The State Department was flooded with telegrams. Senators and Congressmen were urged to use their influence to get money to stranded Americans to help them home. The 235 U.S. diplomatic and consular representatives were asked to locate Americans and see to their comfort and safety. Not until Americans realised how closely they were related to Europe could they picture themselves as having a direct interest in the war. Then the stock market began to tumble. The New York Stock Exchange was closed. South America asked New York for credit and supplies, and neutral Europe, as well as China in the Far East, looked to the United States to keep the war within bounds. Uncle Sam became the Atlas of the world and nearly every belligerent requested this government to take over its diplomatic and consular interests in enemy countries. Diplomacy, commerce, finance and shipping suddenly became dependent upon this country. Not only the belligerents but the neutrals sought the leadership of a nation which could look after all the interests, except those of purely military and naval operations. The eyes of the world centred upon Washington. President Wilson, as the official head of the government, was signalled out as the one man to help them in their suffering and to listen to their appeals. The belligerent governments addressed their protests and their notes to Wilson. Belgium sent a special commission to gain the President's ear. The peace friends throughout the world, even those in the belligerent countries, looked to Wilson for guidance and help.

In August, 1914, Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, the President's wife, was dangerously ill. I was at the White House every day to report the developments there for the United Press. On the evening of the 5th of August Secretary Tumulty called the correspondents and told them that the President, who was deeply distressed by the war, and who was suffering personally because of his wife's illness, had written at his wife's bedside the following message:

"As official head of one of the powers signatory to The Hague Convention, I feel it to be my privilege and my duty, under Article III of that Convention, to say to you in the spirit of most earnest friendship that I should welcome an opportunity to act in the interests of European peace, either now or at any other time that might be thought more suitable, as an occasion to serve you and all concerned in a way that would afford me lasting cause for gratitude and happiness.

"(Signed) WOODROW WILSON."

The President's Secretary cabled this to the Emperors of Germany and Austria-Hungary; the King of England, the Czar of Russia and the President of France. The President's brief note touched the chord of sympathy of the whole world; but it was too late then to stop the war. European statesmen had been preparing for a conflict. With the public support which each nation had, each government wanted to fight until there was a victory.

One of the first things which seemed to appeal to President Wilson was the fact that not only public opinion of Europe, but of America, sought a spokesman. Unlike Roosevelt, who led public opinion, unlike Taft, who disregarded it, Wilson took the attitude that the greatest force in the world was public opinion. He believed public opinion was greater than the presidency. He felt that he was the man the American people had chosen to interpret and express their opinion. Wilson's policy was to permit public opinion to rule America. Those of us who spent two years in Germany could see this very clearly.

The President announced the plank for his international policy when he spoke at the annual meeting of the American Bar Association, at Washington, shortly after the war began.

"The opinion of the world is the mistress of the world," he said, "and the processes of international law are the slow processes by which opinion works its will. What impresses me is the constant thought that that is the tribunal at the bar of which we all sit. I would call your attention, incidentally, to the circumstance that it does not observe the ordinary rules of evidence; which has sometimes suggested to me that the ordinary rules of evidence had shown some signs of growing antique. Everything, rumour included, is heard in this court, and the standard of judgment is not so much the character of the testimony as the character of the witness. The motives are disclosed, the purposes are conjectured and that opinion is finally accepted which seems to be, not the best founded in law, perhaps, but the best founded in integrity of character and of morals. That is the process which is slowly working its will upon the world; and what we should be watchful of is not so much jealous interests as sound principles of action. The disinterested course is not alone the biggest course to pursue; but it is in the long run the most profitable course to pursue. If you can establish your character you can establish your credit.

"Understand me, gentlemen, I am not venturing in this presence to impeach the law. For the present, by the force of circumstances, I am in part the embodiment of the law and it would be very awkward to disavow myself. But I do wish to make this intimation, that in this time of world change, in this time when we are going to find out just how, in what particulars, and to what extent the real facts of human life and the real moral judgments of mankind prevail, it is worth while looking inside our municipal law and seeing whether the judgments of the law are made square with the moral judgments of mankind. For I believe that we are custodians of the spirit of righteousness, of the spirit of equal handed justice, of the spirit of hope which believes in the perfectibility of the law with the perfectibility of human life itself.

"Public life, like private life, would be very dull and dry if it were not for this belief in the essential beauty of the human spirit and the belief that the human spirit should be translated into action and into ordinance. Not entire. You cannot go any faster than you can advance the average moral judgment of the mass, but you can go at least as fast as that, and you can see to it that you do not lag behind the average moral judgments of the mass. I have in my life dealt with all sorts and conditions of men, and I have found that the flame of moral judgment burns just as bright in the man of humble life and limited experience as in the scholar and man of affairs. And I would like his voice always to be heard, not as a witness, not as speaking in his own case, but as if he were the voice of men in general, in our courts of justice, as well as the voice of the lawyers, remembering what the law has been. My hope is that, being stirred to the depths by the extraordinary circumstances of the time in which we live, we may recover from those steps something of a renewal of that vision of the law with which men may be supposed to have started out in the old days of the oracles, who commune with the intimations of divinity."

Before this war, very few nations paid any attention to public opinion. France was probably the beginner. Some twenty years before 1914, France began to extend her civilisation to Russia, Italy, the Balkans and Syria. In Roumania, today, one hears almost as much French as Roumanian spoken. Ninety per cent of the lawyers in Bucharest were educated in Paris. Most of the doctors in Roumania studied in France. France spread her influence by education.

The very fact that the belligerents tried to mobilise public opinion in the United States in their favour shows that 1914 was a milestone in international affairs. This was the first time any foreign power ever attempted to fight for the good will--the public opinion--of this nation. The governments themselves realised the value of public opinion in their own boundaries, but when the war began they realised that it was a power inside the realms of their neighbours, too.

When differences of opinion developed between the United States and the belligerents the first thing President Wilson did was to publish all the documents and papers in the possession of the American government relating to the controversy. The publicity which the President gave the diplomatic correspondence between this government and Great Britain over the search and seizure of vessels emphasised in Washington this tendency in our foreign relations. At the beginning of England's seizure of American merchantmen carrying cargoes to neutral European countries, the State Department lodged individual protests, but no heed was paid to them by the London officials. Then the United States made public the negotiations seeking to accomplish by publicity what a previous exchange of diplomatic notes failed to do.

Discussing this action of the President in an editorial on "Diplomacy in the Dark," the New York World said:

"President Wilson's protest to the British Government is a clear, temperate, courteous assertion of the trade rights of neutral countries in time of war. It represents not only the established policy of the United States but the established policy of Great Britain. It voices the opinion of practically all the American people, and there are few Englishmen, even in time of war, who will take issue with the principles upheld by the President. Yet a serious misunderstanding was risked because it is the habit of diplomacy to operate in the dark.

"Fortunately, President Wilson by making the note public prevented the original misunderstanding from spreading. But the lesson ought not to stop there. Our State Department, as Mr. Wickersham recently pointed out in a letter to the World, has never had a settled policy of publicity in regard to our diplomatic affairs. No Blue Books or White Books are ever issued. What information the country obtains must be pried out of the Department. This has been our diplomatic policy for more than a century, and it is a policy that if continued will some day end disastrously."

Speaking in Atlanta in 1912, President Wilson stated that this government would never gain another foot of territory by conquest. This dispelled whatever apprehension there was that the United States might seek to annex Mexico. Later, in asking Congress to repeal the Panama Tolls Act of 1912, the President said the good will of Europe was a more valuable asset than commercial advantages gained by discriminatory legislation.

Thus at the outset of President Wilson's first administration, foreign powers were given to understand that Mr. Wilson believed in the power of public opinion; that he favoured publicity as a means of accomplishing what could not be done by confidential negotiations; that he did not believe in annexation and that he was ready at any time to help end the war.

Before the Blockade

President Wilson's policy during the first six months of the war was one of impartiality and neutrality. The first diplomatic representative in Washington to question the sincerity of the executive was Dr. Constantine Dumba, the exiled Austro-Hungarian Ambassador, who was sent to the United States because he was not a noble, and, therefore, better able to understand and interpret American ways! He asked me one day whether I thought Wilson was neutral. He said he had been told the President was pro-English. He believed, he said, that everything the President had done so far showed he sympathised with the Entente. While we were talking I recalled what the President's stenographer, Charles L. Swem, said one day when we were going to New York with the President.

"I am present at every conference the President holds," he stated. "I take all his dictation. I think he is the most neutral man in America. I have never heard him express an opinion one way or the other, and if he had I would surely know of it."

I told Dr. Dumba this story, which interested him, and he made no comments.

As I was at the White House nearly every day I had an opportunity to learn what the President would say to callers and friends, although I was seldom privileged to use the information. Even now I do not recall a single statement which ever gave me the impression that the President sided with one group of belligerents.

The President's sincerity and firm desire for neutrality was emphasised in his appeal to "My Countrymen."

"The people of the United States," he said, "are drawn from many nations, and chiefly from the nations now at war. It is natural and inevitable that there should be the utmost variety of sympathy and desire among them with regard to the issues and circumstances of the conflict. Some will wish one nation, others another, to succeed in the momentous struggle. It will be easy to excite passion and difficult to allay it. Those responsible for exciting it will assume a heavy responsibility, responsibility for no less a thing than that the people of the United States, whose love of their country and whose loyalty to the government should unite them as Americans all, bound in honour and affection to think first of her and her interests, may be divided in camps of hostile opinion, hot against each other, involved in the war itself in impulse and opinion, if not in action.

"My thought is of America. I am speaking, I feel sure, the earnest wish and purpose of every thoughtful American that this great country of ours, which is of course the first in our thoughts and in our hearts, should show herself in this time of peculiar trial a nation fit beyond others to exhibit the fine poise of undisturbed judgment, the dignity of self-control, the efficiency of dispassionate action; a nation that neither sits in judgment upon others nor is disturbed in her own counsels and which keeps herself fit and free to do what is honest and disinterested and truly serviceable for the peace of the world."

Many Americans believed even early in the war that the United States should have protested against the invasion of Belgium. Others thought the government should prohibit the shipments of war supplies to the belligerents. America was divided by the great issues in Europe, but the great majority of Americans believed with the President, that the best service Uncle Sam could render would be to help bring about peace.

Until February, 1915, when the von Tirpitz submarine blockade of England was proclaimed, only American interests, not American lives, had been drawn into the war. But when the German Admiralty announced that neutral as well as belligerent ships in British waters would be sunk without warning, there was a new and unexpected obstacle to neutrality. The high seas were as much American as British. The oceans were no nation's property and they could not justly be used as battlegrounds for ruthless warfare by either belligerent.

Germany, therefore, was the first to challenge American neutrality. Germany was the first to threaten American lives. Germany, which was the first to show contempt for Wilson, forced the President, as well as the people, to alter policies and adapt American neutrality to a new and grave danger.

On February 4th, 1915, the Reichsanzeiger, the official newspaper of Germany, published an announcement declaring that from the 18th of February "all the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland as well as the entire English channel are hereby declared to be a war area. All ships of the enemy mercantile marine found in these waters will be destroyed and it will not always be possible to avoid danger to the crews and passengers thereon.

"Neutral shipping is also in danger in the war area, as owing to the secret order issued by the British Admiralty January 31st, 1915, regarding the misuse of neutral flags, and the chances of naval warfare, it can happen that attacks directed against enemy ships may damage neutral vessels.

"The shipping route around the north of The Shetlands in the east of the North Sea and over a distance of thirty miles along the coast of The Netherlands will not be dangerous."

Although the announcement was signed by Admiral von Pohl, Chief of the Admiralty Staff, the real author of the blockade was Grand Admiral von Tirpitz. In explanation of the announcement the Teutonic-Allied, neutral and hostile powers were sent a memorandum which contained the following paragraph:

"The German Government announces its intention in good time so that hostile as well as neutral ships can take necessary precautions accordingly. Germany expects that the neutral powers will show the same consideration for Germany's vital interests as for those of England, and will aid in keeping their citizens and property from this area. This is the more to be expected, as it must be to the interests of the neutral powers to see this destructive war end as soon as possible."

On February 12th the American Ambassador, James W. Gerard, handed Secretary of State von Jagow a note in which the United States said:

"This Government views these possibilities with such grave concern that it feels it to be its privilege, and indeed its duty in the circumstances, to request the Imperial German Government to consider before action is taken the critical situation in respect of the relations between this country and Germany which might arise were the German naval officers, in carrying out the policy foreshadowed in the Admiralty's proclamation, to destroy any merchant vessel of the United States or cause the death of American citizens.

"It is of course unnecessary to remind the German Government that the sole right of a belligerent in dealing with neutral vessels on the high seas is limited to visit and search, unless a blockade is proclaimed and effectively maintained, which the Government of the United States does not understand to be proposed in this case. To declare and exercise the right to attack and destroy any vessel entering a prescribed area of the high seas without first accurately determining its belligerent nationality and the contraband character of its cargo, would be an act so unprecedented in naval warfare that this Government is reluctant to believe that the Imperial German Government in this case contemplates it as possible."

I sailed from New York February 13th, 1915, on the first American passenger liner to run the von Tirpitz blockade. On February 20th we passed Queenstown and entered the Irish Sea at night. Although it was moonlight and we could see for miles about us, every light on the ship, except the green and red port and starboard lanterns, was extinguished. As we sailed across the Irish Sea, silently and cautiously as a muskrat swims on a moonlight night, we received a wireless message that a submarine, operating off the mouth of the Mersey River, had sunk an English freighter. The captain was asked by the British Admiralty to stop the engines and await orders. Within an hour a patrol boat approached and escorted us until the pilot came aboard early the next morning. No one aboard ship slept. Few expected to reach Liverpool alive, but the next afternoon we were safe in one of the numerous snug wharves of that great port.

A few days later I arrived in London. As I walked through Fleet street newsboys were hurrying from the press rooms carrying orange-coloured placards with the words in big black type: "Pirates Sink Another Neutral Ship."

Until the middle of March I remained in London, where the wildest rumours were afloat about the dangers off the coast of England, and where every one was excited and expectant over the reports that Germany was starving. I was urged by friends and physicians not to go to Germany because it was universally believed in Great Britain that the war would be over in a very short time. On the 15th of March I crossed from Tilbury to Rotterdam. At Tilbury I saw pontoon bridges across the Thames, patrol boats and submarine chasers rushing back and forth watching for U-boats, which might attempt to come up the river. I boarded the Batavia IV late at night and left Gravesend at daylight the next morning for Holland. Every one was on deck looking for submarines and mines. The channel that day was as smooth as a small lake, but the terrible expectation that submarines might sight the Dutch ship made every passenger feel that the submarine war was as real as it was horrible.

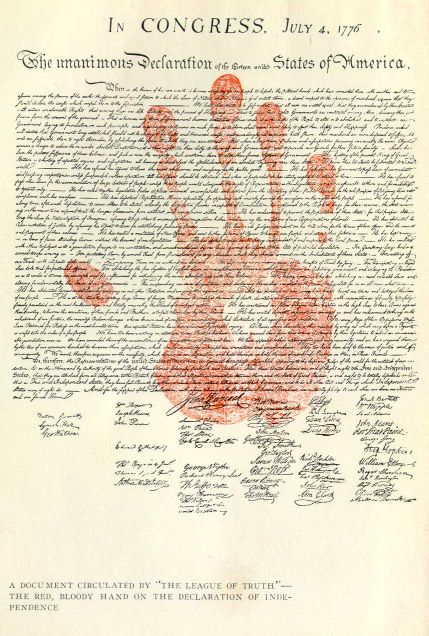

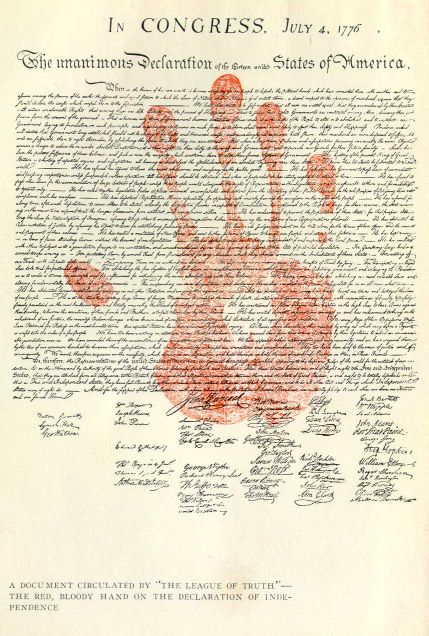

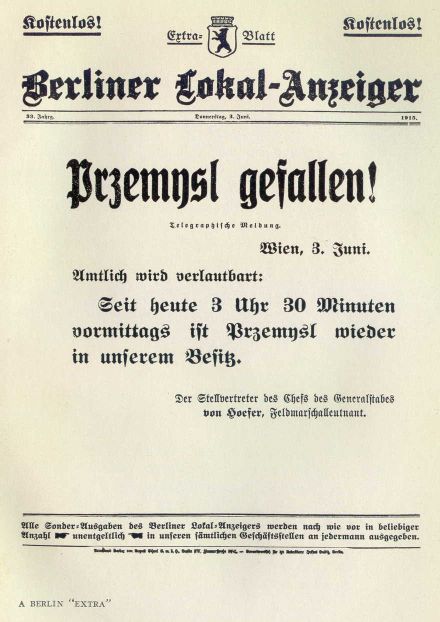

On the 17th of March, arriving at the little German border town of Bentheim, I met for the first time the people who were already branded as "Huns and Barbarians" by the British and French. Officers and people, however, were not what they had been pictured to be. Neither was Germany starving. The officials and inspectors were courteous and patient and permitted me to take into Germany not only British newspapers, but placards which pictured the Germans as pirates. Two days later, while walking down Unter den Linden, poor old women, who were already taking the places of newsboys, sold German extras with streaming headlines: "British Ships Sunk. Submarine War Successful." In front of the Lokal Anzeiger building stood a large crowd reading the bulletins about the progress of the von Tirpitz blockade.

For luncheon that day I had the choice of as many foods as I had had in London. The only thing missing was white bread, for Germany, at the beginning of the war, permitted only Kriegsbrot (war bread) to be baked.

All Berlin streets were crowded and busy. Military automobiles, auto-trucks, big moving vans, private automobiles, taxi-cabs and carriages hurried hither and thither. Soldiers and officers, seemingly by the thousands, were parading up and down. Stores were busy. Berlin appeared to be as normal as any other capital. Even the confidence of Germany in victory impressed me so that in one of my first despatches I said:

"Germany to-day is more confident than ever that all efforts of her enemies to crush her must prove in vain. With a threefold offensive, in Flanders, in Galicia and in northwest Russia, being successfully prosecuted, there was a spirit of enthusiasm displayed here in both military and civilian circles that exceeded even the stirring days immediately following the outbreak of the war.

"Flags are flying everywhere to-day; the Imperial standards of Germany and Austria predominate, although there is a goodly showing of the Turkish Crescent. Bands are playing as regiment after regiment passes through the city to entrain for the front. Through Wilhelmstrasse the soldiers moved, their hats and guns decorated with fragrant flowers and with mothers, sisters and sweethearts clinging to and encouraging them."

A few weeks before I arrived the Germans were excited over the shipment of arms and ammunitions from the United States to the Allies, but by the time I was in Berlin the situation seemed to have changed. On April 4th I telegraphed the following despatch which appeared in the Evening Sun, New York:

"The spirit of animosity towards Americans which swept Germany a few weeks ago seems to have disappeared. The 1,400 Americans in Berlin and those in the smaller cities of Germany have little cause to complain of discourteous treatment. Americans just arriving in Berlin in particular comment upon the friendliness of their reception. The Germans have been especially courteous, they declare, on learning of their nationality. Feeling against the United States for permitting arms to be shipped to the Allies still exists, but I have not found this feeling extensive among the Germans. Two American doctors studying in German clinics declare that the wounded soldiers always talk about 'Amerikanische keugel' (American bullets), but it is my observation that the persons most outspoken against the sale of ammunition to the Allies by American manufacturers are the American residents of Berlin."

Two weeks later the situation had changed considerably. On the 24th I telegraphed: "Despite the bitter criticism of the United States by German newspapers for refusing to end the traffic in munitions, it is semi-officially explained that this does not represent the real views of the German Government. The censor has been instructed to permit the newspapers to express themselves frankly on this subject and on Secretary Bryan's reply to the von Bernstorff note, but it has been emphasised that their views reflect popular opinion and the editorial side of the matter and not the Government.

"The Lokal Anzeiger, following up its attack of yesterday, to-day says:

"'The answer of the United States is no surprise to Germany and naturally it fails to convince Germany that a flourishing trade in munitions of war is in accord with strict neutrality. The German argument was based upon the practice of international law, but the American reply was based upon the commercial advantages enjoyed by the ammunition shippers.'"

April 24th was von Tirpitz day. It was the anniversary of the entrance of the Grand Admiral in the German Navy fifty years before, and the eighteenth anniversary of his debut in the cabinet, a record for a German Minister of Marine. There was tremendous rejoicing throughout the country, and the Admiral, who spent his Prussian birthday at the Navy Department, was overwhelmed with congratulations. Headed by the Kaiser, telegrams came from every official in Germany. The press paid high tribute to his blockade, declaring that it was due to him alone that England was so terror-stricken by submarines.

I was not in Germany very long until I was impressed by the remarkable control the Government had on public opinion by censorship of the press. People believe, without exception, everything they read in the newspapers. And I soon discovered that the censor was so accustomed to dealing with German editors that he applied the same standards to the foreign correspondents. A reporter could telegraph not what he observed and heard, but what the censors desired American readers to hear and know about Germany.

I was in St. Quentin, France (which the Germans on their 1917 withdrawal set on fire) at the headquarters of General von Below, when news came May 8th that the Lusitania was torpedoed. I read the bulletins as they arrived. I heard the comments of the Germans who were waging war in an enemy country. I listened as they spoke of the loss of American and other women and children. I was amazed when I heard them say that a woman had no more right on the Lusitania than she would have on an ammunition wagon on the Somme. The day before I was in the first line trenches on the German front which crossed the road running from Peronne to Albert. At that time this battlefield, which a year and a half later was destined to be the scene of the greatest slaughter in history, was as quiet and beautiful as this picturesque country of northern France was in peace times. Only a few trenches and barbed wire entanglements marred the scene.

On May 9th I left St. Quentin for Brussels. Here I was permitted by the General Government to send a despatch reflecting the views of the German army in France about the sinking of the Lusitania. I wrote what I thought was a fair article. I told how the bulletin was posted in front of the Hotel de Ville; how the officers and soldiers marching to and away from the front stopped, read, smiled and congratulated each other because the Navy was at last helping the Army "win the war." There were no expressions of regret over the loss of life. These officers and soldiers had seen so many dead, soldiers and civilians, men and women, in Belgium and France that neither death nor murder shocked them.

The telegram was approved by the military censor and forwarded to Berlin. I stayed in Belgium two days longer, went to Louvain and Liége and reached Berlin May 12th. The next day I learned at the Foreign Office that my despatch was stopped because it conflicted with the opinions which the German Government was sending officially by wireless to Washington and to the American newspapers. I felt that this was unfair, but I was subject to the censorship and had no appeal.

I did not forget this incident because it showed a striking difference of opinion between the army, which was fighting for Germany, and the Foreign Office, which was explaining and excusing what the Army and Navy did. The Army always justified the events in Belgium, but the Foreign Office did not. And this was the first incident which made me feel that even in Germany, which was supposed to be united, there were differences of opinion.

In September, 1915, while the German army was moving against Russia like a surging sea, I was invited to go to the front near Vilna. During the intervening months I had observed and recorded as much as possible the growing indignation in Germany because the United States permitted the shipment of arms and ammunition to the Allies. In June I had had an interview with Secretary of State von Jagow, in which he protested against the attitude of the United States Government and said that America was not acting as neutral as Germany did during the Spanish-American war. He cited page 168 of Andrew D. White's book in which Ambassador White said he persuaded Germany not to permit a German ship laden with ammunition and consigned for Spain to sail. I thought that if Germany had adopted such an attitude toward America, that in justice to Germany Washington should adopt the same position. After von Jagow gave me the facts in possession of the Foreign Office and after he had loaned me Mr. White's book, I looked up the data. I found to my astonishment that Mr. White reported to the State Department that a ship of ammunition sailed from Hamburg, and that he had not protested, although the Naval Attaché had requested him to do so. The statements of von Jagow and Mr. White's in his autobiography did not agree with the facts. Germany did send ammunition to Spain, but Wilhelmstrasse was using Mr. White's book as proof that the Krupp interests did not supply our enemy in 1898. The latter part of September I entered Kovno, the important Russian fortress, eight days after the army captured it. I was escorted, together with other foreign correspondents, from one fort to another and shown what the 42 cm. guns had destroyed. I saw 400 machine guns which were captured and 1,300 pieces of heavy artillery. The night before, at a dinner party, the officers had argued against the United States because of the shipment of supplies to Russia. They said that if the United States had not aided Russia, that country would not have been able to resist the invaders. I did not know the facts, but I accepted their statements. When I was shown the machine guns, I examined them and discovered that every one of the 400 was made at Essen or Magdeburg, Germany. Of the 1,300 pieces of artillery every cannon was made in Germany except a few English ship guns. Kovno was fortified by German artillery, not American.

A few days later I entered Vilna; this time I was moving with the advance column. At dinner that night with General von Weber, the commander of the city, the subject of American arms and ammunition was again brought up. The General said they had captured from the Russians an American machine gun. He added that they were bringing it in from Smorgon to show the Americans. When it reached us the stamp, written in English, showed that it was manufactured by Vickers Limited, England. Being unable to read English, the officer who reported the capture thought the gun was made in the United States.

In Roumania last December I followed General von Falkenhayn's armies to the forts of Bucharest. On Thanksgiving Day I crossed by automobile the Schurduck Pass. The Roumanians had defended, or attempted to defend, this road by mounting armoured guns on the crest of one of the mountain ranges in the Transylvanian Alps. I examined a whole position here and found all turrets were made in Germany.

I did not doubt that the shipment of arms and ammunition to the Allies had been a great aid to them. (I was told in Paris, later, on my way to the United States that if it had not been for the American ammunition factories France would have been defeated long ago.) But when Germany argued that the United States was not neutral in permitting these shipments to leave American ports, Germany was forgetting what her own arms and munition factories had done for Germany's enemies. When the Krupp works sold Russia the defences for Kovno, the German Government knew these weapons would be used against Germany some day, because no nation except Germany could attack Russia by way of that city. When Krupps sold war supplies to Roumania, the German Government knew that if Roumania joined the Allies these supplies would be used against German soldiers. But the Government was careful not to report these facts in German newspapers. And, although Secretary of State von Jagow acknowledged to Ambassador Gerard that there was nothing in international law to justify a change in Washington's position, von Jagow's statements were not permitted to be published in Germany.

To understand Germany's resentment over Mr. Wilson's interference with the submarine warfare, three things must be taken into consideration.

1. The Allies' charge that all Germans are "Huns and Barbarians."

2. The battle of the Marne and the shipment of arms and ammunition from the United States.

3. The intrigue and widening breach between the Army and Navy and the Foreign Office.

One weapon the Allies used against Germany, which was more effective than all others, was the press. When the English and French indicted the Germans as "Barbarians and Huns," as "pirates," and "uncivilised" Europeans, it cut the Germans to the quick; it affected men and women so terribly that Germans feared these attacks more than they did the combined military might of their enemies. This is readily understood when one realises that before the war the thing the Germans prided themselves on was their commerce and their civilisation,--their Kultur. Before the war, the world was told by every German what the nation had done for the poor; what strides the scientists had made in research work and what progress the business men had made in extending their commerce at the expense of competitors.

While some government officials foresaw the disaster which would come to Germany if this national vanity was paraded before the whole world, their advice and counsel were ignored. Consul General Kiliani, the Chief German official in Australia before the war, told me he had reported repeatedly to the Foreign Office that German business men were injuring their own opportunities by bragging so much of what they had done, and what they would do. He said if it continued the whole world would be leagued against Germany; that public opinion would be so strong against German goods that they would lose their markets. Germany made the whole world fear her commercial might by this foolish bragging.

So when the war broke out and Germans were attacked for being uncivilised in Belgium, for breaking treaties and for disregarding the opinion of the world, it was but natural that German vanity should resent it. Germans feared nothing but God and public opinion. They had such exalted faith in their army they believed they could gain by Might what they had lost in prestige throughout the world. This is one of the reasons the German people arose like one man when war was declared. They wished and were ready to show the world that they were the greatest people ever created.

The German explanation of why they lost the battle of the Marne is interesting, not alone because of the explanation of the defeat, but because it shows why the shipment of arms and ammunition from the United States was such a poisonous pill to the army. Shortly after my arrival in Berlin Dr. Alfred Zimmermann, then Under Secretary of State, said the greatest scandal in Germany after the war would be the investigation of the reasons for the shortage of ammunition in September, 1914. He did not deny that Germany was prepared for a great war. He must have known at the time what the Director of the Post and Telegraph knew on the 2nd of August, 1914, when he wrote Announcement No. 3. The German Army must have known the same thing and if it had prepared for war, as every German admits it had, then preparations were made to fight nine nations. But there was one thing which Germany failed to take into consideration, Zimmermann said, and that was the shipment of supplies from the United States. Then, he added, there were two reasons why the battle of the Marne was lost: one, because there was not sufficient ammunition; and, two, because the reserves were needed to stop the Russian invasion of East Prussia. I asked him whether Germany did not have enormous stores of ammunition on hand when the war began. He said there was sufficient ammunition for a short campaign, but that the Ministry of War had not mobilised sufficient ammunition factories to keep up the supplies. He said this was the reason for the downfall of General von Herringen, who was Minister of War at the beginning of hostilities.

After General von Kluck was wounded and returned to his villa in Wilmersdorf, a suburb of Berlin, I took a walk with him in his garden and discussed the Marne. He confirmed what Zimmermann stated about the shortage of ammunition and added that he had to give up his reserves to General von Hindenburg, who had been ordered by the Kaiser to drive the Russians from East Prussia.

At the very beginning of the war, although no intimations were permitted to reach the outside world, there was a bitter controversy between the Foreign Office, as headed by the Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg; the Navy Department, headed by Grand Admiral von Tirpitz, and General von Moltke, Chief of the General Staff. The Chancellor delayed mobilisation of the German Army three days. For this he never has and never will be forgiven by the military authorities. During those stirring days of July and August, when General von Moltke, von Tirpitz, von Falkenhayn, Krupps and the Rhine Valley Industrial leaders were clamouring for war and for an invasion of Belgium, the Kaiser was being urged by the Chancellor and the Foreign Office to heed the proposals of Sir Edward Grey for a Peace Conference. But the Kaiser, who was more of a soldier than a statesman, sided with his military friends. The war was on, not only between Germany and the Entente, but between the Foreign Office and the Army and Navy. This internal fight which began in July, 1914, became Germany's bitterest struggle and from time to time the odds went from one side to another. The Army accused the diplomats of blundering in starting the war. The Foreign Office replied that it was the lust for power and victory which poisoned the military leaders which caused the war. Belgium was invaded against the counsel of the Foreign Office. But when the Chancellor was confronted with the actual invasion and the violation of the treaty, he was compelled by force of circumstance, by his position and responsibility to the Kaiser to make his famous speech in the Reichstag in which he declared: "Emergency knows no law."

But when the allied fleet swept German ships from the high seas and isolated a nation which had considered its international commerce one of its greatest assets, considerable animosity developed between the Army and Navy. The Army accused the Navy of stagnation. Von Tirpitz, who had based his whole naval policy upon a great navy, especially upon battleship and cruiser units, was confronted by his military friends with the charge that he was not prepared. As early as 1908 von Tirpitz had opposed the construction of submarines. Speaking in the Reichstag when naval appropriations were debated, he said Germany should rely upon a battleship fleet and not upon submarines. But when he saw his great inactive Navy in German waters, he switched to the submarine idea of a blockade of England. In February, 1915, he announced his submarine blockade of England with the consent of the Kaiser, but without the approval of the Foreign Office.

By this time the cry, "Gott strafe England," had become the most popular battle shout in Germany. The von Tirpitz blockade announcement made this battlecry real. It made him the national hero. The German press, which at that time was under three different censors, turned its entire support over night to the von Tirpitz plan. The Navy Department, which even then was not only anti-British but anti-American, wanted to sink every ship on the high seas. When the United States lodged its protests on February 12th the German Navy wanted to ignore it. The Foreign Office was inclined to listen to President Wilson's arguments. Even the people, while they were enthusiastic for a submarine war, did not want to estrange America if they could prevent it. The von Tirpitz press bureau, which knew that public opposition to its plan could be overcome by raising the cry that America was not neutral in aiding the Allies with supplies, launched an anti-American campaign. It came to a climax one night when Ambassador Gerard was attending a theatre party. As he entered the box he was recognised by a group of Germans who shouted insulting remarks because he spoke English. Then some one else remarked that America was not neutral by shipping arms and ammunition.

The Foreign Office apologised the next day but the Navy did not. And, instead of listening to the advice of Secretary of State von Jagow, the Navy sent columns of inspired articles to the newspapers attacking President Wilson and telling the German people that the United States had joined the Entente in spirit if not in action.

At the beginning of the war, even the Socialist Party in the Reichstag voted the Government credits. The press and the people unanimously supported the Government because there was a very terrorising fear that Russia was about to invade Germany and that England and France were leagued together to crush the Fatherland. Until the question of the submarine warfare came up, the division of opinion which had already developed between the Army and Navy clique and the Foreign Office was not general among the people. Although the army had not taken Paris, a great part of Belgium and eight provinces of Northern France were occupied and the Russians had been driven from East Prussia. The German people believed they were successful. The army was satisfied with what it had done and had great plans for the future. Food and economic conditions had changed very little as compared to the changes which were to take place before 1917. Supplies were flowing into Germany from all neutral European countries. Even England and Russia were selling goods to Germany indirectly through neutral countries. Considerable English merchandise, as well as American products, came in by way of Holland because English business men were making money by the transaction and because the English Government had not yet discovered leaks in the blockade. Two-thirds of the butter supply in Berlin was coming from Russia. Denmark was sending copper. Norway was sending fish and valuable oils. Sweden was sending horses and cattle. Italy was sending fruit. Spanish sardines and olives were reaching German merchants. There was no reason to be dissatisfied with the way the war was going. And, besides, the German people hated their enemies so that the leaders could count upon continued support for almost an indefinite period. The cry of "Hun and Barbarian" was answered with the battle cry "Gott strafe England."

The latter part of April on my first trip to the front I dined at Great Headquarters (Grosse Haupt Quartier) in Charleville, France, with Major Nicolai, Chief of the Intelligence Department of the General Staff. The next day, in company with other correspondents, we were guests of General von Moehl and his staff at Peronne. From Peronne we went to the Somme front to St. Quentin, to Namur and Brussels. The soldiers were enthusiastic and happy. There was plenty of food and considerable optimism. But the confidence in victory was never so great as it was immediately after the sinking of the Lusitania. That marked the crisis in the future trend of the war.

Up to this time the people had heard very little about the fight between the Navy and the Foreign Office. But gradually rumours spread. While there was previously no outlet for public opinion, the Lusitania issue was debated more extensively and with more vigour than the White Books which were published to explain the causes of the war.

With the universal feeling of self confidence, it was but natural that the people should side with the Navy in demanding an unrestricted submarine warfare. When Admiral von Bachmann gave the order to First Naval Lieutenant Otto Steinbrink to sink the Lusitania, he knew the Navy was ready to defy the United States or any other country which might object. He knew, too, that von Tirpitz was very close to the Kaiser and could count upon the Kaiser's support in whatever he did. The Navy believed the torpedoing of the Lusitania would so frighten and terrorise the world that neutral shipping would become timid and enemy peoples would be impressed by Germany's might on the seas. Ambassador von Bernstorff had been ordered by the Foreign Office to put notices in the American papers warning Americans off these ships. The Chancellor and Secretary von Jagow knew there was no way to stop the Admiralty, and they wanted to avoid, if possible, the loss of American lives.

The storm of indignation which encircled the globe when reports were printed that over a thousand people lost their lives on the Lusitania, found a sympathetic echo in the Berlin Foreign Office. "Another navy blunder," the officials said--confidentially. Foreign Office officials tried to conceal their distress because the officials knew the only thing they could do now was to make preparation for an apology and try to excuse in the best possible way what the navy had done. On the 17th of May like a thunderbolt from a clear sky came President Wilson's first Lusitania note.

"Recalling the humane and enlightened attitude hitherto assumed by the Imperial German Government in matters of international life, particularly with regard to the freedom of the seas; having learned to recognise German views and German influence in the field of international obligations as always engaged upon the side of justice and humanity;" the note read, "and having understood the instructions of the Imperial German Government to its naval commanders to be upon the same plane of human action as those prescribed by the naval codes of other nations, the government of the United States is loath to believe--it cannot now bring itself to believe--that these acts so absolutely contrary to the rules and practices and spirit of modern warfare could have the countenance or sanction of that great government. . . . Manifestly submarines cannot be used against merchantmen as the last few weeks have shown without an inevitable violation of many sacred principles of justice and humanity. American citizens act within their indisputable rights in taking their ships and in travelling wherever their legitimate business calls them upon the high seas, and exercise those rights in what should be a well justified confidence that their lives will not be endangered by acts done in clear violation of universally acknowledged international obligations and certainly in the confidence that their own government will sustain them in the exercise of their rights."

And then the note which Mr. Gerard handed von Jagow concluded with these words:

"It (The United States) confidently expects therefore that the Imperial German Government will disavow the acts of which the United States complains, that they will make reparation as far as reparation is possible for injuries which are without measure, and that they will take immediate steps to prevent the recurrence of anything so obviously subversive of the principles of warfare, for which the Imperial German Government in the past so wisely and so firmly contended. The Government and people of the United States look to the Imperial German Government for just, prompt and enlightened action in this vital matter. . . . Expressions of regret and offers of reparation in the case of neutral ships sunk by mistake, while they may satisfy international obligations if no loss of life results, cannot justify or excuse a practice, the natural necessary effect of which is to subject neutral nations or neutral persons to new and immeasurable risks. The Imperial German Government will not expect the Government of the United States to omit any word, or any act, necessary to the performance of its sacred duty of maintaining the rights of the United States and its citizens, and of safeguarding their free exercise and enjoyment."

Never in history had a neutral nation indicted another as the United States did Germany in its first Lusitania note without immediately going to war. Because the Foreign Office feared the reaction it might have upon the people, the newspapers were not permitted to publish the text until the press bureaus of the Navy and the Foreign Office had mobilised the editorial writers and planned a publicity campaign to follow the note's publication. But the Navy and Foreign Office could not agree on what should be done. The Navy wanted to ignore Wilson. Naval officers laughed at President Wilson's impertinence and, when the Foreign Office sent to the Admiralty for all data in possession of the Navy Department regarding the sinking of the Lusitania the Navy refused to acknowledge the request.

During this time I was in constant touch with the Foreign Office and the American Embassy. Frequently I went to the Navy Department but was always told they had nothing to say. When it appeared, however, that there might he a break in diplomatic relations over the Lusitania the Kaiser called the Chancellor to Great Headquarters for a conference. Meanwhile Germany delayed her reply to the American note because the Navy and Foreign Office were still at loggerheads. On the 31st of May von Jagow permitted me to quote him in an interview saying:

"America can hardly expect us to give up any means at our disposal to fight our enemy. It is a principle with us to defend ourselves in every possible way. I am sure that Americans will be reasonable enough to believe that our two countries cannot discuss the Lusitania matter until both have the same basis of facts."

The American people were demanding an answer from Germany and because the two branches of the Government could not agree on what should be said von Jagow had to do something to gain time. Germany, therefore, submitted in her reply of the 28th of May certain facts about the Lusitania for the consideration of the American Government saying that Germany reserved final statements of its position with regard "to the demands made in connection with the sinking of the Lusitania until a reply was received from the American Government." After the note was despatched the chasm between the Navy and Foreign Office was wider than ever. Ambassador Gerard, who went to the Foreign Office daily, to try to convince the officials that they were antagonising the whole world by their attitude on the Lusitania question, returned to the Embassy one day after a conference with Zimmermann and began to prepare a scrap book of cartoons and clippings from American newspapers. Two secretaries were put to work pasting the comments, interviews, editorials and cartoons reflecting American opinion in the scrap book. Although the German Foreign Office had a big press department its efforts were devoted more to furnishing the outside world with German views than with collecting outside opinions for the information of the German Government. Believing that this information would be of immeasurable benefit to the German diplomats in sounding the depths of public sentiment in America, Gerard delivered the book to von Jagow personally.

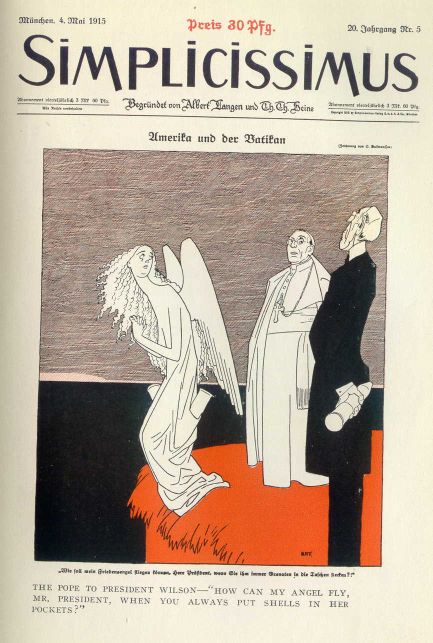

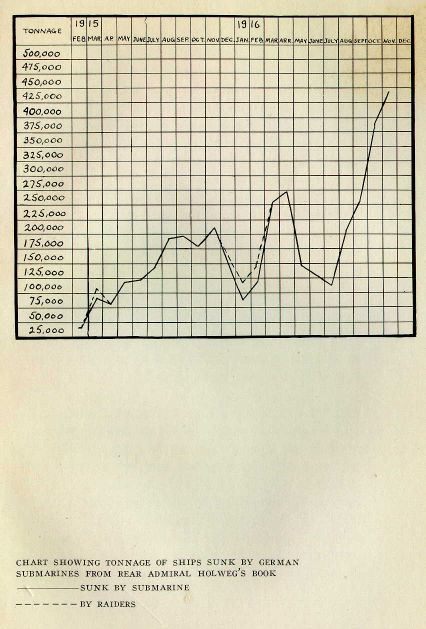

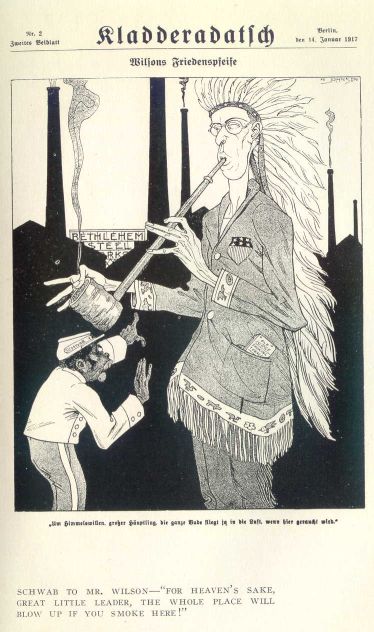

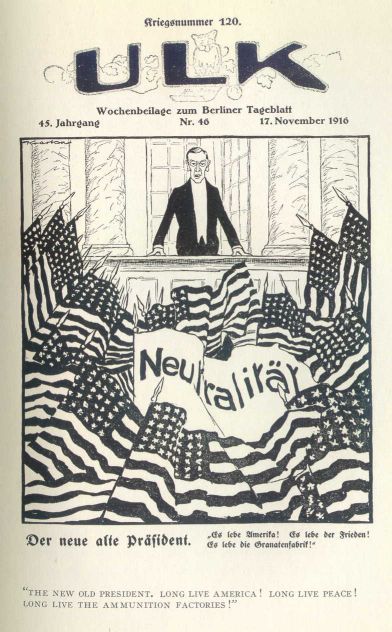

In the meantime numerous conferences were held at Great Headquarters. Financiers, business men and diplomats who wanted to keep peace with America sided with the Foreign Office. Every anti-American influence in the Central Powers joined forces with the Navy. The Lusitania note was printed and the public discussion which resulted was greater than that which followed the first declarations of war in August, 1914. The people, who before had accepted everything their Government said, began to think for themselves. One heard almost as much criticism as praise of the Lusitania incident. For the first time the quarrel, which had been nourished between the Foreign Office and the Admiralty, became nation-wide and forces throughout Germany lined up with one side or the other. But the Navy Department was the cleverer of the two. The press bureau sent out inspired stories that the submarines were causing England a loss of a million dollars a week. They said that every week the Admiralty was launching two U-boats. It was stated that reliable reports to Admiral von Tirpitz proved the high toll taken by the submarines in two weeks had struck terror to the hearts of English ship-owners. The newspapers printed under great headlines: "Toll of Our Tireless U-Boats," the names and tonnage of ships lost. The press bureau pointed to the rise in food prices in Great Britain and France. The public was made to feel a personal pride in submarine exploits. And at the same time the Navy editorial writers brought up the old issue of American arms and ammunition to further embitter the people.

Thus the first note which President Wilson wrote in the Lusitania case not only brought the quarrel between the Navy and Foreign Office to a climax but it gave the German people the first opportunity they had had seriously to discuss questions of policy and right.

In the Rhine Valley, where the ammunition interests dominated every phase of life, the Navy found its staunchest supporters. In educational circles, in shipping centres, such as Hamburg and Bremen, in the financial districts of Frankfort and Berlin, the Foreign Office received its support. Press and Reichstag were divided. Supporting the Foreign Office were the Lokal Anzeiger, the Berliner Tageblatt, the Cologne Gazette, the Frankforter Zeitung, the Hamburger Fremdemblatt, and the Vorwärts.

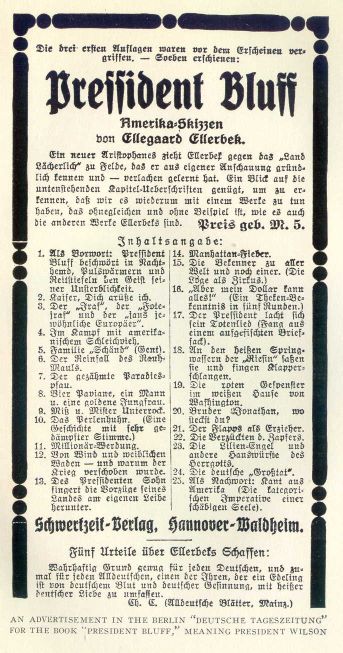

The Navy had the support of Count Reventlow, Naval Critic of the Deutsche Tageszeitung, the Täglische Rundscha, the Vossische Zeitung, the Morgen Post, the B. Z. Am Mittag, the Münchener Neueste Nachrichten, the Rheinische Westfälische Zeitung, and the leading Catholic organ, the Koelnische Volks-Zeitung.

Government officials were also divided. Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg led the party which demanded an agreement with the United States. He was supported by von Jagow, Zimmermann, Dr. Karl Helfferich, Secretary of the Treasury; Dr. Solf, the Colonial Minister; Dr. Siegfried Heckscher, Vice Chairman of the Reichstag Committee on Foreign Relations; and Philip Scheidemann, leader of the majority of the Socialists in the Reichstag.

The opposition was led by Grand Admiral von Tirpitz. He was supported by General von Falkenhayn, Field Marshal von Mackensen and all army generals; Admirals von Pohl and von Bachmann; Major Bassermann, leader of the National Liberal Party in the Reichstag; Dr. Gustav Stressemann, member of the Reichstag and Director of the North German Lloyd Steamship Company; and von Heydebrand, the so-called "Uncrowned King of Prussia," because of his control of the Prussian Diet.

With these forces against each other the internal fight continued more bitter than ever. President Wilson kept insisting upon definite promises from Germany but the Admiralty still had the upper hand. There was nothing for the Foreign Office to do except to make the best possible excuses and depend upon Wilson's patience to give them time to get into the saddle. The Navy Department, however, was so confident that it had the Kaiser's support in everything it did, that one of the submarines was instructed to sink the Arabic.

President Wilson's note in the Arabic case again brought the submarine dispute within Germany to a head. Conferences were again held at Great Headquarters. The Chancellor, von Jagow, Helfferich, von Tirpitz and other leaders were summoned by the Kaiser. On the 28th of August I succeeded in sending by courier to The Hague the following despatch:

"With the support of the Kaiser, the German Chancellor, Dr. von Bethmann-Hollweg, is expected to win the fight he is now making for a modification of Germany's submarine warfare that will forever settle the difficulties with America over the sinking of the Lusitania and the Arabic. Both the Chancellor and von Jagow are most anxious to end at once and for all time the controversies with Washington desiring America's friendship." (Published in the Chicago Tribune, August 29th, 1915.)

"The Marine Department, headed by von Tirpitz, creator of the submarine policy, will oppose any disavowal of the action of German's submarines. But the Kaiser is expected to approve the steps the Chancellor and Foreign Secretary contemplate taking, swinging the balance in favour of von Bethmann-Hollweg's contention that ships in the future must be warned before they are torpedoed."

One day I went to the Foreign Office and told one of the officials I believed that if the American people knew what a difficult time the Foreign Office was having in trying to win out over the Admiralty that public opinion in the United States might be mobilised to help the Foreign Office against the Admiralty. I took with me a brief despatch which I asked him to pass. He censored it with the understanding that I would never disclose his name in case the despatch was read in Germany.

A few days later the Manchester, England, Guardian arrived containing my article, headed as follows:

HOLLWEG'S CHANGE OF TUNE

Respect for Scraps of Paper

LAW AT SEA

Insists on Warning by Submarines

TIRPITZ PARTY BEATEN

Kaiser Expected to Approve New Policy

"New York, Sunday.

"Cables from Mr. Carl W. Ackerman, Berlin correspondent of the United Press published here, indicate that the real crisis following the Arabic is in Germany, not America. He writes:

"The Berlin Foreign Office is unalterably opposed to submarine activity, such as evidenced by the Arabic affair, and it was on the initiative of this Government department that immediate steps were taken with Mr. Gerard the American Ambassador. The nature of these negotiations is still unknown to the German public.

"It is stated on the highest authority that Herr von Jagow, Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg are unanimous in their anxiety to settle American difficulties once and for all, retaining the friendship of the United States in any event.

"The Kaiser is expected to approve the course suggested by the Imperial Chancellor, despite open opposition to any disavowal of submarine activities which constantly emanates from the German Admiralty.

"The Chancellor is extremely desirous of placing Germany on record as an observer of international law as regards sea warfare, and in this case will win his demand that submarines in the future shall thoroughly warn enemy ships before firing their torpedoes or shells.

"There is considerable discussion in official circles as to whether the Chancellor's steps create a precedent, but it is agreed that it will probably close all complications with America, including the Lusitania case, which remained unsettled following President Wilson's last note to Germany.

"Thus if the United States approves the present attitude of the Chancellor this step will aid in clearing the entire situation and will materially strengthen the policy of von Bethmann-Hollweg and von Jagow, which is a deep desire for peace with America."

After this despatch was printed I was called to the home of Fran von Schroeder, the American-born wife of one of the Intelligence Office of the General Staff. Captain Vanselow, Chief of the Admiralty Intelligence Department, was there and had brought with him the Manchester Guardian. He asked me where I got the information and who had passed the despatch. He said the Navy was up in arms and had issued orders to the General Telegraph Office that, inasmuch as Germany was under martial law, no telegrams were to be passed containing the words submarines, navy, admiralty or marine or any officers of the Navy without having them referred to the Admiralty for a second censoring. This order practically nullified the censorship powers of the Foreign Office. I saw that the Navy Department was again in the saddle and that the efforts of the Chancellor to maintain peace might not be successful after all. But the conferences at Great Headquarters lasted longer than any one expected. The first news we received of what had taken place was that Secretary von Jagow had informed the Kaiser he would resign before he would do anything which might cause trouble with the United States.

Germany was split wide open by the submarine issue. For a while it looked as if the only possible adjustment would be either for von Tirpitz to go and his policies with him, or for von Jagow and the Chancellor to go with the corresponding danger of a rupture with America. But von Tirpitz would not resign. He left Great Headquarters for Berlin and intimated to his friends that he was going to run the Navy to suit himself. But the Chancellor who had the support of the big shipping interests and the financiers, saw a possible means of checkmating von Tirpitz by forcing Admiral von Pohl to resign as Chief of the Admiralty Staff. They finally persuaded the Kaiser to accept his resignation and appoint Admiral von Holtzendorff as his successor. Von Holtzendorff's brother was a director of the Hamburg-American Line and an intimate friend of A. Ballin, the General Director of the company. The Chancellor believed that by having a friend of his as Chief of the Admiralty Staff, no orders would be issued to submarine commanders contrary to the wishes of the Chancellor, because according to the rules of the German Navy Department the Chief of the Admiralty Staff must approve all naval plans and sign all orders to fleet commanders.