The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Doctor's Dilemma, by Hesba Stretton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Doctor's Dilemma Author: Hesba Stretton Release Date: December 24, 2004 [EBook #14454] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DOCTOR'S DILEMMA *** Produced by Steven Gibbs and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team

AN OPEN DOOR.

I think I was as nearly mad as I could be; nearer madness, I believe, than I shall ever be again, thank God! Three weeks of it had driven me to the very verge of desperation. I cannot say here what had brought me to this pass, for I do not know into whose hands these pages may fall; but I had made up my mind to persist in a certain line of conduct which I firmly believed to be right, while those who had authority over me, and were stronger than I was, were resolutely bent upon making me submit to their will. The conflict had been going on, more or less violently, for months; now I had come very near the end of it. I felt that I must either yield or go mad. There was no chance of my dying; I was too strong for that. There was no other alternative than subjection or insanity.

It had been raining all the day long, in a ceaseless, driving torrent, which had kept the streets clear of passengers. I could see nothing but wet flag-stones, with little pools of water lodging in every hollow, in which the rain-drops splashed heavily whenever the storm grew more in earnest. Now and then a tradesman's cart, or a cab, with their drivers wrapped in mackintoshes, dashed past; and I watched them till they were out of my sight. It had been the dreariest of days. My eyes had followed the course of solitary drops rolling down the window-panes, until my head ached. Toward nightfall I could distinguish a low, wailing tone, moaning through the air; a quiet prelude to a coming change in the weather, which was foretold also by little rents in the thick mantle of cloud, which had shrouded the sky all day. The storm of rain was about to be succeeded by a storm of wind. Any change would be acceptable to me.

There was nothing within my room less dreary than without. I was in London, but in what part of London I did not know. The house was one of those desirable family residences, advertised in the Times as to be let furnished, and promising all the comforts and refinements of a home. It was situated in a highly-respectable, though not altogether fashionable quarter; as I judged by the gloomy, monotonous rows of buildings which I could see from my windows: none of which were shops, but all private dwellings. The people who passed up and down the streets on line days were all of one stamp, well-to-do persons, who could afford to wear good and handsome clothes; but who were infinitely less interesting than the dear, picturesque beggars of Italian towns, or the sprightly, well-dressed peasantry of French cities. The rooms on the third floor—my rooms, which I had not been allowed to leave since we entered the house, three weeks before—were very badly furnished, indeed, with comfortless, high horse-hair-seated chairs, and a sofa of the same uncomfortable material, cold and slippery, on which it was impossible to rest. The carpet was nearly threadbare, and the curtains of dark-red moreen were very dingy; the mirror over the chimney-piece seemed to have been made purposely to distort my features, and produce in me a feeling of depression. My bedroom, which communicated with this agreeable sitting-room by folding-doors, was still smaller and gloomier; and opened upon a dismal back-yard, where a dog in a kennel howled dejectedly from time to time, and rattled his chain, as if to remind me that I was a prisoner like himself. I had no books, no work, no music. It was a dreary place to pass a dreary time in; and my only resource was to pace to and fro—to and fro from one end to another of those wretched rooms.

I watched the day grow dusk, and then dark. The rifts in the driving clouds were growing larger, and the edges were torn. I left off roaming up and down my room, like some entrapped creature, and sank down on the floor by the window, looking out for the pale, sad blue of the sky which gleamed now and then through the clouds, till the night had quite set in. I did not cry, for I am not given to overmuch weeping, and my heart was too sore to be healed by tears; neither did I tremble, for I held out my hand and arm to make sure they were steady; but still I felt as if I were sinking down—down into an awful, profound despondency, from which I should never rally; it was all over with me. I had nothing before me but to give up, and own myself overmatched and conquered. I have a half-remembrance that as I crouched there in the darkness I sobbed once, and cried under my breath, "God help me!"

A very slight sound grated on my ear, and a fresh thrill of strong, resentful feeling quivered all through me; it was the hateful click of the key turning in the lock. It gave me force enough to carry out my defiance a little longer. Before the door could be opened I sprang to my feet, and stood erect, and outwardly very calm, gazing through the window, with my face turned away from the persons who were coming in; I was so placed that I could see them reflected in the mirror over the fireplace. A servant came first, carrying in a tray, upon which were a lamp and my tea—such a meal as might be prepared for a school-girl in disgrace.

She came up to me, as if to draw down the blinds and close the shutters.

"Leave them," I said; "I will do it myself by-and-by."

"He's not coming home to-night," said a woman's voice behind me, in a scoffing tone.

I could see her too without turning round. A handsome woman, with bold black eyes, and a rouged face, which showed coarsely in the ugly looking-glass. She was extravagantly dressed, and wore a profusion of ornaments—tawdry ones, mostly, but one or two I recognized as my own. She was not many years older than myself. I took no notice whatever of her, or her words, or her presence; but continued to gaze out steadily at the lamp-lit streets and stormy sky. Her voice grew hoarse with passion, and I knew well how her face would burn and flush under the rouge.

"It will be no better for you when he is at home," she said, fiercely. "He hates you; he swears so a hundred times a day, and he is determined to break your proud spirit for you. We shall force you to knock under sooner or later; and I warn you it will be best for you to be sooner rather than later. What friends have you got anywhere to take your side? If you'd made friends with me, my fine lady, you'd have found it good for yourself; but you've chosen to make me your enemy, and I'll make him your enemy. You know, as well as I do, he can't hear the sight of your long, puling face."

Still I did not answer by word or sign. I set my teeth together, and gave no indication that I had heard one of her taunting speeches. My silence only served to fan her fury.

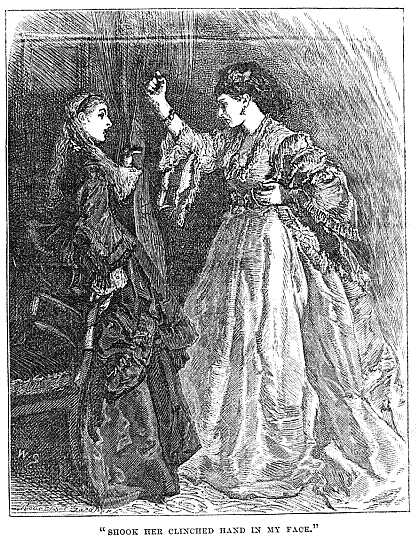

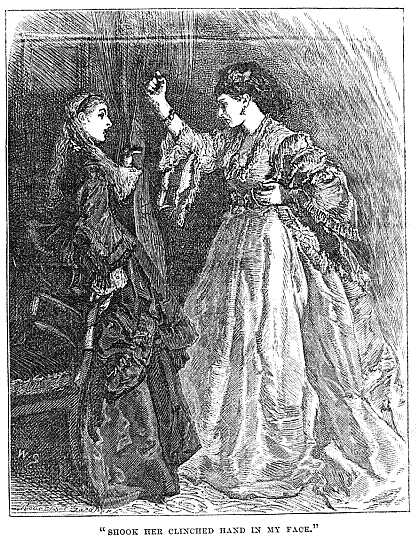

"Upon my soul, madam," she almost shrieked, "you are enough to drive me to murder! I could beat you, standing there so dumb, as if I was not worthy to speak a word to. Ay! and I would, but for him. So, then, three weeks of this hasn't broken you down yet! but you are only making it the worse for yourself; we shall try other means to-morrow."

She had no idea how nearly my spirit was broken, for I gave her no reply. She came up to where I stood, and shook her clinched hand in my face—a large, well-shaped hand, with bejewelled fingers, that could have given me a heavy blow. Her face was dark with passion; yet she was maintaining some control over herself, though with great difficulty. She had never struck me yet, but I trembled and shrank from her, and was thankful when she flung herself out of the room, pulling the door violently after her, and locking it noisily, as if the harsh, jarring sounds would be more terrifying than the tones of her own voice.

Left to myself I turned round to the light, catching a fresh glimpse of my face in the mirror—a pale and sadder and more forlorn face than before. I almost hated myself in that glass. But I was hungry, for I was young, and my health and appetite were very good; and I sat down to my plain fare, and ate it heartily. I felt stronger and in better spirits by the time I had finished the meal; I resolved to brave it out a little longer. The house was very quiet; for at present there was no one in it except the woman and the servant who had been up to my room. The servant was a poor London drudge, who was left in charge by the owners of the house, and who had been forbidden to speak to me. After a while I heard her heavy, shambling footsteps coming slowly up the staircase, and passing my door on her way to the attics above; they sounded louder than usual, and I turned my head round involuntarily. A thin, fine streak of light, no thicker than a thread, shone for an instant in the dark corner of the wall close by the door-post, but it died away almost before I saw it. My heart stood still for a moment, and then beat like a hammer. I stole very softly to the door, and discovered that the bolt had slipped beyond the hoop of the lock; probably in the sharp bang with which it had been closed. The door was open for me!

TO SOUTHAMPTON.

There was not a moment to be lost. When the servant came downstairs again from her room in the attics, she would be sure to call for the tea-tray, in order to save herself another journey; how long she would be up-stairs was quite uncertain. If she was gone to "clean" herself, as she called it, the process might be a very long one, and a good hour might be at my disposal; but I could not count upon that. In the drawing-room below sat my jailer and enemy, who might take a whim into her head, and come up to see her prisoner at any instant. It was necessary to be very quick, very decisive, and very silent.

I had been on the alert for such a chance ever since my imprisonment began. My seal-skin hat and jacket lay ready to my hand in a drawer; but I could find no gloves; I could not wait for gloves. Already there were ominous sounds overhead, as if the servant had dispatched her brief business there, and was about to come down. I had not time to put on thicker boots; and it was perhaps essential to the success of my flight to steal down the stairs in the soft, velvet slippers I was wearing. I stepped as lightly as I could—lightly but very swiftly, for the servant was at the top of the upper flight, while I had two to descend. I crept past the drawing-room door. The heavy house-door opened with a grating of the hinges; but I stood outside it, in the shelter of the portico; free, but with the rain and wind of a stormy night in October beating against me, and with no light save the glimmer of the feeble street-lamps flickering across the wet pavement.

I knew very well that my escape was almost hopeless, for the success of it depended very much upon which road of the three lying before me I should happen to take. I had no idea of the direction of any one of them, for I had never been out of the house since the night I was brought to it. The strong, quick running of the servant, and the passionate fury of the woman, would overtake me if we were to have a long race; and if they overtook me they would force me back. I had no right to seek freedom in this wild way, yet it was the only way. Even while I hesitated in the portico of the house that ought to have been my home, I heard the shrill scream of the girl within when she found my door open, and my room empty. If I did not decide instantaneously, and decide aright, it would have been better for me never to have tried this chance of escape.

But I did not linger another moment. I could almost believe an angel took me by the hand, and led me. I darted straight across the muddy road, getting my thin slippers wet through at once, ran for a few yards, and then turned sharply round a corner into a street at the end of which I saw the cheery light of shop-windows, all in a glow in spite of the rain. On I fled breathlessly, unhindered by any passer-by, for the rain was still falling, though more lightly. As I drew nearer to the shop-windows, an omnibus-driver, seeing me run toward him, pulled up his horses in expectation of a passenger. The conductor shouted some name which I did not hear, but I sprang in, caring very little where it might carry me, so that I could get quickly enough and far enough out of the reach of my pursuers. There had been no time to lose, and none was lost. The omnibus drove on again quickly, and no trace was left of me.

I sat quite still in the farthest corner of the omnibus, hardly able to recover my breath after my rapid running. I was a little frightened at the notice the two or three other passengers appeared to take of me, and I did my best to seem calm and collected. My ungloved hands gave me some trouble, and I hid them as well as I could in the folds of my dress; for there was something remarkable about the want of gloves in any one as well dressed as I was. But nobody spoke to me, and one after another they left the omnibus, and fresh persons took their places, who did not know where I had got in. I did not stir, for I determined to go as far as I could in this conveyance. But all the while I was wondering what I should do with myself, and where I could go, when it readied its destination.

There was one trifling difficulty immediately ahead of me. When the omnibus stopped I should have no small change for paying my fare. There was an Australian sovereign fastened to my watch-chain which I could take off, but it would be difficult to detach it while we were jolting on. Besides, I dreaded to attract attention to myself. Yet what else could I do?

Before I had settled this question, which occupied me so fully that I forgot other and more serious difficulties, the omnibus drove into a station-yard, and every passenger, inside and out, prepared to alight. I lingered till the last, and sat still till I had unfastened my gold-piece. The wind drove across the open space in a strong gust as I stepped down upon the pavement. A man had just descended from the roof, and was paying the conductor: a tall, burly man, wearing a thick water-proof coat, and a seaman's hat of oil-skin, with a long flap lying over the back of his neck. His face was brown and weather-beaten, but he had kindly-looking eyes, which glanced at me as I stood waiting to pay my fare.

"Going down to Southampton?" said the conductor to him.

"Ay, and beyond Southampton," he answered.

"You'll have a rough night of it," said the conductor.—"Sixpence, if you please, miss."

I offered him my Australian sovereign, which he turned over curiously, asking me if I had no smaller change. He grumbled when I answered no, and the stranger, who had not passed on, but was listening to what was said, turned pleasantly to me.

"You have no change, mam'zelle?" he asked, speaking rather slowly, as if English was not his ordinary speech. "Very well! are you going to Southampton?"

"Yes, by the next train," I answered, deciding upon that course without hesitation.

"So am I, mam'zelle," he said, raising his hand to his oil-skin cap; "I will pay this sixpence, and you can give it me again, when you buy your ticket in the office."

I smiled quickly, gladly; and he smiled back upon me, but gravely, as if his face was not used to a smile. I passed on into the station, where a train was standing, and people hurrying about the platform, choosing their carriages. At the ticket-office they changed my Australian gold-piece without a word; and I sought out my seaman friend to return the sixpence he had paid to me. He had done me a greater kindness than he could ever know, and I thanked him heartily. His honest, deep-set, blue eyes glistened under their shaggy eyebrows as they looked down upon me.

"Can I do nothing more for you, mam'zelle?" he asked. "Shall I see after your luggage?"

"Oh! that will be all right, thank you," I replied, "but is this the train for Southampton, and how soon will it start?"

I was watching anxiously the stream of people going to and fro, lest I should see some person who knew me. Yet who was there in London who could know me?

"It will be off in five minutes," answered the seaman. "Shall I look out a carriage for you?"

He was somewhat careful in making his selection; finally he put me into a compartment where there were only two ladies, and he stood in front of the door, but with his back turned toward it, until the train was about to start. Then he touched his hat again with a gesture of farewell, and ran away to a second-class carriage.

I sighed with satisfaction as the train rushed swiftly through the dimly-lighted suburbs of London, and entered upon the open country. A wan, watery line of light lay under the brooding clouds in the west, tinged with a lurid hue; and all the great field of sky stretching above the level landscape was overcast with storm-wrack, fleeing swiftly before the wind. At times the train seemed to shake with the Wast, when it was passing oyer any embankment more than ordinarily exposed; but it sped across the country almost as rapidly as the clouds across the sky. No one in the carriage spoke. Then came over me that weird feeling familiar to all travellers, that one has been doomed to travel thus through many years, and has not half accomplished the time. I felt as if I had been fleeing from my home, and those who should have been my friends, for a long and weary while; yet it was scarcely an hour since I had made my escape.

In about two hours or more—but exactly what time I did not know, for my watch had stopped—my fellow-passengers, who had scarcely condescended to glance at me, alighted at a large, half-deserted station, where only a few lamps were burning. Through the window I could see that very few other persons were leaving the train, and I concluded we had not yet reached the terminus. A porter came up to me as I leaned my head through the window.

"Going on, miss?" he asked.

"Oh, yes!" I answered, shrinking back into my corner-seat. He remained upon the step, with his arm over the window-frame, while the train moved on at a slackened pace for a few minutes, and then pulled up, but at no station. Before me lay a dim, dark, indistinct scene, with little specks of light twinkling here and there in the night, but whether on sea or shore I could not tell. Immediately opposite the train stood the black hulls and masts and funnels of two steamers, with a glimmer of lanterns on their decks, and up and down their shrouds. The porter opened the door for me.

"You've only to go on board, miss," he said, "your luggage will be seen to all right." And he hurried away to open the doors of the other carriages.

I stood still, utterly bewildered, for a minute or two, with the wind tossing my hair about, and the rain beating in sharp, stinging drops like hailstones upon my face and hands. It must have been close upon midnight, and there was no light but the dim, glow-worm glimmer of the lanterns on deck. Every one was hurrying past me. I began almost to repent of the desperate step I had taken; but I had learned already that there is no possibility of retracing one's steps. At the gangways of the two vessels there were men shouting hoarsely. "This way for the Channel Islands!" "This way for Havre and Paris!" To which boat should I trust myself and my fate? There was nothing to guide me. Yet once more that night the moment had come when I was compelled to make a prompt, decisive, urgent choice. It was almost a question of life and death to me: a leap in the dark that must be taken. My great terror was lest my place of refuge should be discovered, and I be forced back again. Where was I to go? To Paris, or to the Channel Islands?

A ROUGH NIGHT AT SEA.

A mere accident decided it. Near the fore-part of the train I saw the broad, tall figure of my new friend, the seaman, making his way across to the boat for the Channel Islands; and almost involuntarily I made up my mind to go on board the same steamer, for I had an instinctive feeling that he would prove a real friend, if I had need of one. He did not see me following; no doubt he supposed I had left the train at Southampton, having only taken my ticket so far; though how I had missed Southampton I could not tell. The deck was wet and slippery, and the confusion upon it was very great. I was too much at home upon a steamer to need any directions; and I went down immediately into the ladies' cabin, which was almost empty, and chose a berth for myself in the darkest corner. It was not far from the door, and presently two other ladies came down, with a gentleman and the captain, and held an anxious parley close to me. I listened absently and mechanically, as indifferent to the subject as if it could be of no consequence to me.

"Is there any danger?" asked one of the ladies.

"Well, I cannot say positively there will be no danger," answered the captain; "there's not danger enough to keep me and the crew in port; but it will be a very dirty night in the Channel. If there's no actual necessity for crossing to-night I should advise you to wait, and see how it will be to-morrow. Of course we shall use extra caution, and all that sort of thing. No; I cannot say I expect any great danger."

"But it will be awfully rough?" said the gentleman.

The captain answered only by a sound between a groan and a whistle, as if he could not trust himself to think of words that would describe the roughness. There could be no doubt of his meaning. The ladies hastily determined to drive back to their hotel, and gathered up their small packages and wrappings quickly. I fancied they were regarding me somewhat curiously, but I kept my face away from them carefully. They could only see my seal-skin jacket and hat, and my rough hair; and they did not speak to me.

"You are going to venture, miss?" said the captain, stepping into the cabin as the ladies retreated up the steps.

"Oh, yes," I answered. "I am obliged to go, and I am not in the least afraid."

"You needn't be," he replied, in a hearty voice. "We shall do our best, for our own sakes, and you would be our first care if there was any mishap. Women and children first always. I will send the stewardess to you; she goes, of course."

I sat down on one of the couches, listening for a few minutes to the noises about me. The masts were groaning, and the planks creaking under the heavy tramp of the sailors, as they got ready to start, with shrill cries to one another. Then the steam-engine began to throb like a pulse through all the vessel from stem to stern. Presently the stewardess came down, and recommended me to lie down in my berth at once, which I did very obediently, but silently, for I did not wish to enter into conversation with the woman, who seemed inclined to be talkative. She covered me up well with several blankets, and there I lay with my face turned from the light of the swinging lamp, and scarcely moved hand or foot throughout the dismal and stormy night.

For it was very stormy and dismal as soon as we were out of Southampton waters, and in the rush and swirl of the Channel. I did not fall asleep for an instant. I do not suppose I should have slept had the Channel been, as it is sometimes, smooth as a mill-pond, and there had been no clamorous hissing and booming of waves against the frail planks, which I could touch with my hand. I could see nothing of the storm, but I could hear it: and the boat seemed tossed, like a mere cockle-shell, to and fro upon the rough sea. It did not alarm me so much as it distracted my thoughts, and kept them from dwelling upon possibilities far more perilous to me than the danger of death by shipwreck. A short suffering such a death would be.

My escape and flight had been so unexpected, so unhoped for, that it had bewildered me, and it was almost a pleasure to lie still and listen to the din and uproar of the sea and the swoop of the wind rushing down upon it. Was I myself or no? Was this nothing more than a very coherent, very vivid dream, from which I should awake by-and-by to find myself a prisoner still, a creature as wretched and friendless as any that the streets of London contained? My flight had been too extraordinary a success, so far, for my mind to be able to dwell upon it calmly.

I watched the dawn break through a little port-hole opening upon my berth, which had been washed and beaten by the water all the night long. The level light shone across the troubled and leaden-colored surface of the sea, which seemed to grow a little quieter under its touch. I had fancied during the night that the waves were running mountains high; but now I could see them, they only rolled to and fro in round, swelling hillocks, dull green against the eastern sky, with deep, sullen troughs of a livid purple between them. But the fury of the storm had spent itself, that was evident, and the steamer was making way steadily now.

The stewardess had gone away early in the night, being frightened to death, she said, to seek more genial companionship than mine. So I was alone, with the blending light of the early dawn and that of the lamp burning feebly from the ceiling. I sat up in my berth and cautiously unstitched the lining in the breast of my jacket. Here, months ago, when I first began to foresee this emergency, and while I was still allowed the use of my money, I had concealed one by one a few five-pound notes of the Bank of England. I counted them over, eight of them; forty pounds in all, my sole fortune, my only means of living. True, I had besides these a diamond ring, presented to me under circumstances which made it of no value to me, except for its worth in money, and a watch and chain given to me years ago by my father. A jeweller had told me that the ring was worth sixty pounds, and the watch and chain forty; but how difficult and dangerous it would be for me to sell either of them! Practically my means were limited to the eight bank-notes of five pounds each. I kept out one for the payment of my passage, and then replaced the rest, and carefully pinned them into the unstitched lining.

Then I began to wonder what my destination was. I knew nothing whatever of the Channel Islands, except the names which I had learned at school—Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark. I repeated these over and over again to myself; but which of them we were bound for, or if we were about to call at each one of them, I did not know. I should have been more at home had I gone to Paris.

As the light grew I became restless, and at last I left my berth and ventured to climb the cabin-steps. The fresh air smote upon me almost painfully. There was no rain falling, and the wind had been lulling since the dawn. The sea itself was growing brighter, and glittered here and there in spots where the sunlight fell upon it. All the sailors looked beaten and worn out with the night's toil, and the few passengers who had braved the passage, and were now well enough to come on deck, were weary and sallow-looking. There was still no land in sight, for the clouds hung low on the horizon, and overhead the sky was often overcast and gloomy. It was so cold that, in spite of my warm mantle, I shivered from head to foot.

But I could not bear to go back to the close, ill-smelling cabin, which had been shut up all night. I stayed on deck in the biting wind, leaning over the wet bulwarks and gazing across the desolate sea till my spirits sank like lead. The reaction upon the violent strain on my nerves was coming, and I had no power to resist its influence. I could feel the tears rolling down my cheeks and falling on my hands without caring to wipe them away; the more so as there was no one to see them. What did my tears signify to any one? I was cold, and hungry, and miserable. How lonely I was! how poor! with neither a home nor a friend in the world!—a mere castaway upon the waves of this troublous life!

"Mam'zelle is a brave sailor," said a voice behind me, which I recognized as my seaman of the night before, whom I had wellnigh forgotten; "but the storm is over now, and we shall be in port only an hour or two behind time."

"What port shall we reach?" I asked, not caring to turn round lest he should see my wet eyes and cheeks.

"St. Peter-Port," he answered. "Mam'zelle, then, does not know our islands?"

"No," I said. "Where is St. Peter-Port?"

"In Guernsey," he replied. "Is mam'zelle going to Guernsey or Jersey? Jersey is about two hours' sail from Guernsey. If you were going to land at St. Peter-Port, I might be of some service to you."

I turned round then, and looked at him steadily. His voice was a very pleasant one, full of tones that went straight to my heart and filled me with confidence. His face did not give the lie to it, or cause me any disappointment. He was no gentleman, that was plain; his face was bronzed and weather-beaten, as if he often encountered rough weather. But his deep-set eyes had a steadfast, quiet power in them, and his mouth, although it was almost hidden by hair, had a pleasant curve about it. I could not guess how old he was; he looked a middle-aged man to me. His great, rough hands, which had never worn gloves, were stained and hard with labor; and he had evidently been taking a share in the toil of the night, for his close-fitting, woven blue jacket was wet through, and his hair was damp and rough with the wind and rain. He raised his cap as my eyes looked straight into his, and a faint smile flitted across his grave face.

"I want," I said, suddenly, "to find a place where I can live very cheaply. I have not much money, and I must make it last a long time. I do not mind how quiet the place, or how poor; the quieter the better for me. Can you tell me of such a place?"

"You would want a place fit for a lady?" he said, in a half-questioning tone, and with a glance at my silk dress.

"No," I answered, eagerly. "I mean such a cottage as you would live in. I would do all my own work, for I am very poor, and I do not know yet how I can get my living. I must be very careful of my money till I find out what I can do. What sort of a place do you and your wife live in?"

His face was clouded a little, I thought; and he did not answer me till after a short silence.

"My poor little wife is dead," he answered, "and I do not live in Guernsey or Jersey. We live in Sark, my mother and I. I am a fisherman, but I have also a little farm, for with us the land goes from the father to the eldest son, and I was the eldest. It is true we have one room to spare, which might do for mam'zelle; but the island is far away, and very triste. Jersey is gay, and so is Guernsey, but in the winter Sark is too mournful."

"It will be just the place I want," I said, eagerly; "it would suit me exactly. Can you let me go there at once? Will you take me with you?"

"Mam'zelle," he replied, smiling, "the room must be made ready for you, and I must speak to my mother. Besides, Sark is six miles from Guernsey, and to-day the passage would be too rough for you. If God sends us fair weather I will come back to St. Peter-Port for you in three days. My name is Tardif. You can ask the people in Peter-Port what sort of a man Tardif of the Havre Gosselin is."

"I do not want any one to tell me what sort of a man you are," I said, holding out my hand, red and cold with the keen air. He took it into his large, rough palm, looking down upon me with an air of friendly protection.

"What is your name, mam'zelle?" he inquired.

"Oh! my name is Olivia," I said; then I stopped abruptly, for there flashed across me the necessity for concealing it. Tardif did not seem to notice my embarrassment.

"There are some Olliviers in St. Peter-Port," he said. "Is mam'zelle of the same family? But no, that is not probable."

"I have no relations," I answered, "not even in England. I have very few friends, and they are all far away in Australia. I was born there, and lived there till I was seventeen."'

The tears sprang to my eyes again, and my new friend saw them, but said nothing. He moved off at once to the far end of the dock, to help one of the crew in some heavy piece of work. He did not come hack until the rain began to return—a fine, drizzling rain, which came in scuds across the sea.

"Mam'zelle," he said, "you ought to go below; and I will tell you when we are in sight of Guernsey."

I went below, inexpressibly more satisfied and comforted. What it was in this man that won my complete, unquestioning confidence, I did not know; but his very presence, and the sight of his good, trustworthy face, gave me a sense of security such as I have never felt before or since. Surely God had sent him to me in my great extremity.

A SAFE HAVEN.

We were two hours after time at St. Peter-Port; and then all was hurry and confusion, for goods and passengers had to be landed and embarked for Jersey. Tardif, who was afraid of losing the cutter which would convey him to Sark, had only time to give me the address of a person with whom I could lodge until he came to fetch me to his island, and then he hastened away to a distant part of the quay. I was not sorry that he should miss finding out that I had no luggage of any kind with me.

I was busy enough during the next three days, for I had every thing to buy. The widow with whom I was lodging came to the conclusion that I had lost all my luggage, and I did not try to remove the false impression. Through her assistance I was able to procure all I required, without exciting more notice and curiosity. My purchases, though they were as simple and cheap as I could make them, drew largely upon my small store of money, and as I saw it dwindling away, while I grudged every shilling I was obliged to part with, my spirits sank lower and lower. I had never known the dread of being short of money, and the new experience was, perhaps, the more terrible to me. There was no chance of disposing of the costly dress in which I had journeyed, without arousing too much attention and running too great a risk. I stayed in-doors as much as possible, and, as the weather continued cold and gloomy, I did not meet many persons when I ventured out into the narrow, foreign-looking streets of the town.

But on the third day, when I looked out from my window, I saw that the sky had cleared, and the sun was shining joyously. It was one of those lovely days which come as a lull sometimes in the midst of the equinoctial gales, as if they were weary of the havoc they had made, and were resting with folded wings. For the first time I saw the little island of Sark lying against the eastern sky. The whole length of it was visible, from north to south, with the waves beating against its headlands, and a fringe of silvery foam girdling it. The sky was of a pale blue, as though the rains had washed it as well as the earth, and a few filmy clouds were still lingering about it. The sea beneath was a deeper blue, with streaks almost like a hoar frost upon it, with here and there tints of green, like that of the sky at sunset. A boat with three white sails, which were reflected in the water, was tacking about to enter the harbor, and a second, with amber sails, was a little way behind, but following quickly in its wake. I watched them for a long time. Was either of them Tardif's boat?

That question was answered in about two hours' time by Tardif's appearance at the house. He lifted my little box on to his broad shoulders, and marched away with it, trying vainly to reduce his long strides into steps that would suit me, as I walked beside him. I felt overjoyed that he was come. So long as I was in Guernsey, when every morning I could see the arrival of the packet that had brought me, I could not shake off the fear that it was bringing some one in pursuit of me; but in Sark that would be all different. Besides, I felt instinctively that this man would protect me, and take my part to the very utmost, should any circumstances arise that compelled me to appeal to him and trust him with my secret. I knew nothing of him, but his face was stamped with God's seal of trustworthiness, if ever a human face was.

A second man was in the boat when we reached it, and it looked well laden. Tardif made a comfortable seat for me amid the packages, and then the sails were unfurled, and we were off quickly out of the harbor and on the open sea.

A low, westerly wind was blowing, and fell upon the sails with a strong and equal pressure. We rode before it rapidly, skimming over the low, crested waves almost without a motion. Never before had I felt so perfectly secure upon the water. Now I could breathe freely, with the sense of assured safety growing stronger every moment as the coast of Guernsey receded on the horizon, and the rocky little island grew nearer. As we approached it no landing-place was to be seen, no beach or strand. An iron-bound coast of sharp and rugged crags confronted us, which it seemed impossible to scale. At last we cast anchor at the foot of a great cliff, rising sheer out of the sea, where a ladder hung down the face of the rock for a few feet. A wilder or lonelier place I had never seen. Nobody could pursue and surprise me here.

The boatman who was with us climbed up the ladder, and, kneeling down, stretched out his hand to help me, while Tardif stood waiting to hold me steadily on the damp and slippery rungs. For a moment I hesitated, and looked round at the crags, and the tossing, restless sea.

"I could carry you through the water, mam'zelle," said Tardif, pointing to a hand's breadth of shingle lying between the rocks, "but you will get wet. It will be better for you to mount up here."

I fastened both of my hands tightly round one of the upper rungs, before lifting my feet from the unsteady prow of the boat. But the ladder once climbed, the rest of the ascent was easy. I walked on up a zigzag path, cut in the face of the cliff, until I gained the summit, and sat down to wait for Tardif and his comrade. I could not have fled to a securer hiding-place. So long as my money held out, I might live as peacefully and safely as any fugitive had ever lived.

For a little while I sat looking out at the wild and beautiful scene before me, which no words can tell and no fancy picture to those who have never seen it. The white foam of the waves was so near, that I could see the rainbow colors playing through the bubbles as the sun shone on them. Below the clear water lay a girdle of sunken rocks, pointed as needles, and with edges as sharp as swords, about which the waves fretted ceaselessly, drawing silvery lines about their notched and dented ridges. The cliffs ran up precipitously from the sea, carved grotesquely over their whole surface into strange and fantastic shapes; while the golden and gray lichens embroidered them richly, and bright sea-flowers, and stray tufts of grass, lent them the most vivid and gorgeous hues. Beyond the channel, against the clear western sky, lay the island of Guernsey, rising like a purple mountain out of the opal sea, which lay like a lake between us, sparkling and changing every minute under the light of the afternoon sun.

But there was scarcely time for the exquisite beauty of this scene to sink deeply into my heart just then. Before long I heard the tramp of Tardif and his comrade following me; their heavy tread sent down the loose stones on the path plunging into the sea. They were both laden with part of the boat's cargo. They stopped to rest for a minute or two at the spot where I had sat down, and the other boatman began talking earnestly to Tardif in his patois, of which I did not understand a word. Tardif's face was very grave and sad, indescribably so; and, before he turned to me and spoke, I knew it was some sorrowful catastrophe he had to tell.

"You see how smooth it is, mam'zelle," he said—"how clear and beautiful—down below us, where the waves are at play like little white children? I love them, but they are cruel and treacherous. While I was away there was an accident down yonder, just beyond these rocks. Our doctor, and two gentlemen, and a sailor went out from our little bay below, and shortly after there came on a thick darkness, with heavy rain, and they were all lost, every one of them! Poor Renouf! he was a good friend of mine. And our doctor, too! If I had been here, maybe I might have persuaded them not to brave it."

It was a sad story to hear, yet just then I did not pay much attention to it. I was too much engrossed in my own difficulties and trouble. So far as my experience goes, I believe the heart is more open to other people's sorrows when it is free from burdens of its own. I was glad when Tardif took up his load again and turned his back upon the sea.

WILL IT DO?

Tardif walked on before me to a low, thatched cottage, standing at the back of a small farm-yard. There was no other dwelling in sight, and even the sea was not visible from it. It was sheltered by the steep slope of a hill rising behind it, and looked upon another slope covered with gorse-bushes; a very deep and narrow ravine ran down from it to the hand-breadth of shingle which I had seen from the boat. A more solitary place I could not have imagined; no sign of human life, or its neighborhood, betrayed itself; overhead was a vast dome of sky, with a few white-winged sea-gulls flitting across it, and uttering their low, wailing cry. The roof of sky and the two round outlines of the little hills, and the deep, dark ravine, the end of which was unseen, formed the whole of the view before me.

I felt chilled a little as I followed Tardif down into the dell. He glanced back, with grave, searching eyes, scanning my face carefully. I tried to smile, with a very faint, wan smile, I suppose, for the lightness had fled from my spirits, and my heart was heavy enough, God knows.

"Will it not do, mam'zelle?" he asked, anxiously, and with his slow, solemn utterance; "it is not a place that will do for a young lady like you, is it? I should have counselled you to go on to Jersey, where there is more life and gayety; it is my home, but for you it will be nothing but a dull prison."

"No, no!" I answered, as the recollection of the prison I had fled from flashed across me; "it is a very pretty place and very safe; by-and-by I shall like it as much as you do, Tardif."

The house was a low, picturesque building, with thick walls of stone and a thatched roof, which had two little dormer-windows in it; but at the most sheltered end, farthest from the ravine that led down to the sea, there had been built a small, square room of brick-work. As we entered the fold-yard, Tardif pointed this room out to me as mine.

"I built it," he said, softly, "for my poor little wife; I brought the bricks over from Guernsey in my own boat, and laid nearly every one of them with my own hands; she died in it, mam'zelle. Please God, you will be both happy and safe there!"

We stepped directly from the stone causeway of the yard into the farm-house kitchen—the only sitting-room in the house except my own. It was exquisitely clean, with that spotless and scrupulous cleanliness which appears impossible in houses where there are carpets and curtains, and papered walls. An old woman, very little and bent, and dressed in an odd and ugly costume, met us at the door, dropping a courtesy to me, and looking at me with dim, watery eyes. I was about to speak to her, when Tardif bent down his head, and put his mouth to her ear, shouting to her with a loud voice, but in their peculiar jargon, of which I could not make out a single word.

"My poor mother is deaf," he said to me, "very deaf; neither can she speak English. Most of the young people in Sark can talk in English a little, but she is old and too deaf to learn. She has only once been off the island."

I looked at her, wondering for a moment what she could have to think of, but, with an intelligible gesture of welcome, she beckoned me into my own room. The aspect of it was somewhat dreary; the walls were of bare plaster, but dazzlingly white, with one little black silhouette of a woman's head hanging in a common black frame over the low, open hearth, on which a fire of seaweed was smouldering, with a quantity of gray ashes round the small centre of smoking embers. There was a little round table, uncovered, but as white as snow, and two chairs, one of them an arm-chair, and furnished with cushions. A four-post bedstead, with curtains of blue and white check, occupied the larger portion of the floor.

It was not a luxurious apartment; and for an instant I could hardly realize the fact that it was to be my home for an indefinite period. Some efforts had evidently been made to give it a look of welcome, homely as it was. A pretty china tea cup and saucer, with a plate or two to match, were set out on the deal table, and the cushioned arm-chair had been drawn forward to the hearth. I sat down in it, and buried my face in my hands, thinking, till Tardif knocked at the door, and carried in my trunk.

"Will it do, mam'zelle?" he asked, "will it do?"

"It will do very nicely, Tardif," I answered; "but how ever am I to talk to your mother if she does not know English?"

"Mam'zelle," he said, as he uncorded my trunk, "you must order me as you would a servant. Through the winter I shall always be at hand; and you will soon be used to us and our ways, and we shall be used to you and your ways. I will do my best for you, mam'zelle; trust me, I will study to do my best, and make you very happy here. I will be ready to take you away whenever you desire to go. Look upon me as your hired servant."

He waited upon me all the evening, but with a quick attention to my wants, which I had never met with in any hired servant. It was not unfamiliar to me, for in my own country I had often been served only by men; and especially during my girlhood, when I had lived far away in the country, upon my father's sheep-walk. I knew it was Tardif who fried the fish which came in with my tea; and, when the night closed in, it was he who trimmed the oil-lamp and brought it in, and drew the check curtains across the low casement, as if there were prying eyes to see me on the opposite bank. Then a deep, deep stillness crept over the solitary place—a stillness strangely deeper than that even of the daytime. The wail of the sea-gulls died away, and the few busy cries of the farm-yard ceased; the only sound that broke the silence was a muffled, hollow boom which came up the ravine from the sea.

Before nine o'clock Tardif and his mother had gone up-stairs to their rooms in the thatch; and I lay wearied but sleepless in my bed, listening to these dull, faint, ceaseless murmurs, as a child listens to the sound of the sea in a shell. Was it possible that it was I, myself, the Olivia who had been so loved and cherished in her girlhood, and so hated and tortured in later years, who was come to live under a fisherman's roof, in an island, the name of which I barely knew four days ago?

I fell asleep at last, yet I awoke early; but not so early that the other inmates of the cottage were not up, and about their day's work. It was my wish to wait upon myself, and so diminish the cost of living with these secluded people; but I found it was not to be so; Tardif waited upon me assiduously, as well as his deaf mother. The old woman would not suffer me to do any work in my own room, but put me quietly upon one side when I began to make my bed. Fortunately I had plenty of sewing to employ myself in; for I had taken care not to waste my money by buying ready-made clothes. The equinoctial gales came on again fiercely the day after I had reached Sark; and I stitched away from morning till night, trying to fix my thoughts upon my mechanical work.

When the first week was over, Tardif's mother came to me at a time when her son was away out-of-doors, with a purse in her fingers, and by very plain signs made me understand that it was time I paid the first instalment of my debt to her for board and lodgings. I was anxious about my money. No agreement had been made between us as to what I was to pay. I laid a sovereign down upon the table, and the old woman looked at it carefully, and with a pleased expression; but she put it in her purse, and walked away with it, giving me no change. Not that I altogether expected any change; they provided me with every thing I needed, and waited upon me with very careful service; yet now I could calculate exactly how long I should be safe in this refuge, and the calculation gave me great uneasiness. In a few months I should find myself still in need of refuge, but without the means of paying for it. What would become of me then?

Very slowly the winter wore on. How shall I describe the peaceful monotony, the dull, lonely safety of those dark days and long nights? I had been violently tossed from a life of extreme trouble and peril into a profound, unbroken, sleepy security. At first the sudden change stupefied me; but after a while there came over me an uneasy restlessness, a longing to get away from the silence and solitude, even if it were into insecurity and danger. I began to wonder how the world beyond the little island was going on. No news reached us from without. Sometimes for weeks together it was impossible for an open boat to cross over to Guernsey; even when a cutter accomplished its voyage out and in, no letters could arrive for me. The season was so far advanced when I went to Sark, that those visitors who had been spending a portion of the summer there had already taken their departure, leaving the islanders to themselves. They were sufficient for themselves; they and their own affairs formed the world. Tardif would bring home almost daily little scraps of news about the other families scattered about Sark; but of the greater affairs of life in other countries he could tell me nothing.

Yet why should I call these greater affairs? Each to himself is the centre of the world. It was a more important thing to me that I was safe, than that the freedom of England itself should be secure.

TOO MUCH ALONE.

Yet looking back upon that time, now it is past, and has "rounded itself into that perfect star I saw not when I dwelt therein," it would be untrue to represent myself as in any way unhappy. At times I wished earnestly that I had been born among these people, and could live forever among them.

By degrees I discovered that Tardif led a somewhat solitary life himself, even in this solitary island, with its scanty population. There was an ugly church standing in as central and prominent a situation as possible, but Tardif and his mother did not frequent it. They belonged to a little knot of dissenters, who met for worship in a small room, when Tardif generally took the lead. For this reason a sort of coldness existed between him and the larger portion of his fellow-islanders. But there was a second and more important cause for a slight estrangement. He had married an Englishwoman many years ago, much to the astonishment and disappointment of his neighbors; and since her death he had held himself aloof from all the good women who would have been glad enough to undertake the task of consoling him for her loss. Tardif, therefore, was left very much to himself in his isolated cottage, and his mother's deafness caused her also to be no very great favorite with any of the gossips of the island. It was so difficult to make her understand any thing that could not be expressed by signs, that no one except her son attempted to tell her the small topics of the day.

All this told upon me, and my standing among them. At first I met a few curious glances as I roamed about the island; but my dress was as poor and plain as any of theirs, and I suppose there was nothing in my appearance, setting aside my dress, which could attract them. I learned afterward that Tardif had told those who asked him that my name was Ollivier, and they jumped to the conclusion that I belonged to a family of that name in Guernsey; this shielded me from the curiosity that might otherwise have been troublesome and dangerous. I was nobody but a poor young woman from Guernsey, who was lodging in the spare room of Tardif's cottage.

I set myself to grow used to their mode of life, and if possible to become so useful to them that, when my money was all spent, they might be willing to keep me with them; for I shrank from the thought of the time when I must be thrust out of this nest, lonely and silent as it was. As the long, dismal nights of winter set in, with the wind sweeping across the island for several days together with a dreary, monotonous moan which never ceased, I generally sat by their fire, for I had nobody but Tardif to talk to; and now and then there arose an urgent need within me to listen to some friendly voice, and to hear my own speaking in reply. There were only two books in the house, the Bible and the "Pilgrim's Progress," both of them in French; and I had not learned French beyond the few phrases necessary for travelling. But Tardif began to teach me that, and also to mend fishing-nets, which I persevered in, though the twine cut my fingers. Could I by any means make myself useful to them?

As the spring came on, half my dullness vanished. Sark was more beautiful in its cliff scenery than any thing I had ever seen, or could have imagined. Why cannot I describe it to you? I have but to close my eyes, and my memory paints it for me in my brain, with its innumerable islets engirdling it, as if to ward off its busy, indefatigable enemy, the sea. The long, sunken reefs, lying below the water at high tide, but at the ebb stretching like fortifications about it, as if to make of it a sure stronghold in the sea. The strange architecture and carving of the rocks, with faces and crowned heads but half obliterated upon them; the lofty arches, with columns of fretwork bearing them; the pinnacles, and sharp spires; the fallen masses heaped against the base of the cliffs, covered with seaweed, and worn out of all form, yet looking like the fragments of some great temple, with its treasures of sculpture; and about them all the clear, lucid water swelling and tossing, throwing over them sparkling sheets of foam. And the brilliant tone of the golden and saffron lichens, and the delicate tint of the gray and silvery ones, stealing about the bosses and angles and curves of the rocks, as if the rain and the wind and the frost had spent their whole power there to produce artistic effects. I say my memory paints it again for me; but it is only a memory, a shadow that my mind sees; and how can I describe to you a shadow? When words are but phantoms themselves, how can I use them to set forth a phantom?

Whenever the grandeur of the cliffs had wearied me, as one grows weary sometimes of too long and too close a study of what is great, there was a little, enclosed, quiet graveyard that lay in the very lap of the island, where I could go for rest. It was a small patch of ground, a God's acre, shut in on every side by high hedge-rows, which hid every view from sight except that of the heavens brooding over it. Nothing was to be seen but the long mossy mounds above the dead, and the great, warm, sunny dome rising above them. Even the church was not there, for it was built in another spot, and had a few graves of its own scattered about it.

I was sitting there one evening in the early spring, after the sun had dipped below the line of the high hedge-row, though it was still shining in level rays through it. No sound had disturbed the deep silence for a long time, except the twittering of birds among the branches; for up here even the sea could not be heard when it was calm. I suppose my face was sad, as most human faces are apt to be when the spirit is busy in its citadel, and has left the outworks of the eyes and mouth to themselves. So I was sitting quiet, with my hands clasped about my knees, and my face bent down, when a grave, low voice at my side startled me back to consciousness. Tardif was standing beside me, and looking down upon me with a world of watchful anxiety in his deep eyes.

"You are sad, mam'zelle," he said; "too sad for one so young as you are."

"Oh! everybody is sad, Tardif," I answered; "there is a great deal of trouble for every one in this world. You are often very sad indeed."

"Ah! but I have a cause," he said. "Mam'zelle does not know that she is sitting on the grave of my little wife."

He knelt down beside it as he spoke, and laid his hand gently on the green turf. I would have risen, but he would not let me.

"No," he said, "sit still, mam'zelle. Yes, you would have loved her, poor little soul! She was an Englishwoman, like you, only not a lady; a pretty little English girl, so little I could carry her like a baby. None of my people took to her, and she was very lonely, like you again; and she pined and faded away, just quietly, never saying one word against them. No, no, mam'zelle, I like to see you here. This is a favorite place with you, and it gives me pleasure. I ask myself a hundred times a day, 'Is there any thing I can do to make my young lady happy? Tell me what I can do more than I have done."

"There is nothing, Tardif," I answered, "nothing whatever. If you see me sad sometimes, take no notice of it, for you can do no more for me than you are doing. As it is, you are almost the only friend, perhaps the only true friend, I have in the world."

"May God be true to me only as I am true to you!" he said, solemnly, while his dark skin flushed and his eyes kindled. I looked at him closely. A more honest face one could never see, and his keen blue eyes met my gaze steadfastly. Heavy-hearted as I was just then, I could not help but smile, and all his face brightened, as the sea at its dullest brightens suddenly tinder a stray gleam of sunshine. Without another word we both rose to our feet, and stood side by side for a minute, looking down on the little grave beneath us. I would have gladly changed places then with the lonely English girl, who had pined away in this remote island.

After that short, silent pause, we went slowly homeward along the quiet, almost solitary lanes. Twice we met a fisherman, with his creel and nets across his shoulders, who bade us good-night; but no one else crossed our path.

It was a profound monotony, a seclusion I should not have had courage to face wittingly. But I had been led into it, and I dared not quit it. How long was it to last?

A FALSE STEP.

A day came after the winter storms, early, in March, with all the strength and sweetness of spring in it; though there was sharpness enough in the air to make my veins tingle. The sun was shining with so much heat in it, that I might be out-of-doors all day under the shelter of the rocks, in the warm, southern nooks where the daisies were growing. The birds sang more blithely than they had ever done before; a lark overhead, flinging down his triumphant notes; a thrush whistling clearly in a hawthorn-bush hanging over the cliff; and the cry of the gulls flitting about the rocks; I could hear them all at the same moment, with the deep, quiet tone of the sea sounding below their gay music. Tardif was going out to fish, and I had helped him to pack his basket. From my niche in the rocks I could see him getting out of the harbor, and he had caught a glimpse of me, and stood up in his boat, bareheaded, bidding me good-by. I began to sing before he was quite out of hearing, for he paused upon his oars listening, and had given me a joyous shout, and waved his hat round his head, when he was sure it was I who was singing. Nothing could be plainer than that he had gone away more glad at heart than he had been all the winter, simply because he believed that I was growing lighter-hearted. I could not help laughing, yet being touched and softened at the thought of his pleasure. What a good fellow he was! I had proved him by this time, and knew him to be one of the truest, bravest, most unselfish men on God's earth. How good a thing it was that I had met with him that wild night last October, when I had fled like one fleeing from a bitter slavery! For a few minutes my thoughts hovered about that old, miserable, evil time; but I did not care to ponder over past troubles. It was easy to forget them to-day, and I would forget them. I plucked the daisies, and listened almost drowsily to the birds and the sea, and felt all through me the delicious light and heat of the sun. Now and then I lifted up my eyes, to watch Tardif tacking about on the water. There were several boats out, but I kept his in sight, by the help of a queer-shaped patch upon one of the sails. I wished lazily for a book, but I should not have read it if I had had one. I was taking into my heart the loveliness of the spring day.

By twelve o'clock I knew my dinner would be ready, and I had been out in the fresh air long enough to be quite ready for it. Old Mrs. Tardif would be looking out for me impatiently, that she might get the meal over, and the things cleared away, and order restored in her dwelling. So I quitted my warm nook with a feeling of regret, though I knew I could return to it in an hour.

But one can never return to any thing that is once left. When we look for it again, even though the place may remain, something has vanished from it which can never come back. I never returned to my spring-day upon the cliffs of Sark.

A little crumbling path led round the rock and along the edge of the ravine. I chose it because from it I could see all the fantastic shore, bending in a semicircle toward the isle of Breckhou, with tiny, untrodden bays, covered at this hour with only glittering ripples, and with all the soft and tender shadows of the headlands falling across them. I had but to look straight below me, and I could see long tresses of glossy seaweed floating under the surface of the sea. Both my head and my footing were steady, for I had grown accustomed to giddy heights and venturesome climbing. I walked on slowly, casting many a reluctant glance behind me at the calm waters, with the boats gliding to and fro among the islets. I was just giving my last look to them when the loose stones on the crumbling path gave way under my tread, and before I could recover my foothold I found myself slipping down the almost perpendicular face of the cliff, and vainly clutching at every bramble and tuft of grass growing in its clefts.

AN ISLAND WITHOUT A DOCTOR.

I had not time to feel any fear, for, almost before I could realize the fact that I was falling, I touched the ground. The point from which I had slipped was above the reach of the water, but I fell upon the shingly beach so heavily that I was hardly conscious for a few minutes. When I came to my senses again, I lay still for a little while, trying to make out where I was, and how I came there. I was stunned and bewildered. Underneath me were the smooth, round pebbles, which lie above the line of the tide on a shore covered with shingles. Above me rose a dark, frowning rock, the chilly shadow of which lay across me. Without lifting my head I could see the water on a level with me, but it did not look on a level; its bright crested waves seemed swelling upward to the sky, ready to pour over me and bury me beneath them. I was very faint, and sick, and giddy. The ground felt as if it were about to sink under me. My eyelids closed languidly when I did not keep them open by an effort; and my head ached, and my brain swam with confused fancies.

After some time, and with some difficulty, I comprehended what had happened to me, and recollected that it was already past mid-day, and Mrs. Tardif would be waiting for me. I attempted to stand up, but an acute pain in my foot compelled me to desist. I tried to turn myself upon the pebbles, and my left arm refused to help me. I could not check a sharp cry of suffering as my left hand fell back upon the stones on which I was lying. My fall had cost me something more than a few minutes' insensibility and an aching head. I had no more power to move than one who is bound hand and foot.

After a few vain efforts I lay quite still again, trying to deliberate as well as I could for the pain which racked me. I reckoned up, after many attempts in which first my memory failed me, and then my faculty of calculation, what the time of the high tide would be, and how soon Tardif would come home. As nearly as I could make out, it would be high water in about two hours. Tardif had set off at low water, as his boat had been anchored at the foot of the rock, where the ladder hung; but before starting he had said something about returning at high tide, and running up his boat on the beach of our little bay. If he did that, he must pass close by me. It was Saturday morning, and he was not in the habit of staying out late on Saturdays, that he might prepare for the services of the next day. I might count, then, upon the prospect of him running the boat into the bay, and finding me there in about two hours' time.

It took me a very long time to make out all this, for every now and then my brain seemed to lose its power for a while, and every thing whirled about me. Especially there was that awful sensation of sinking down, down through the pebbles into some chasm that was bottomless. I had never either felt pain or fainted before, and all this alarmed me.

Presently I began to listen to the rustle of the pebbles, as the rising tide flowed over them and fell back again, leaving them all ajar and grating against one another—strange, gurgling, jangling sound that seemed to have some meaning. It was very cold, and a creeping moisture was oozing up from the water. A vague wonder took hold of me as to whether I was really above the line of the tide, for, now the March tides were come, I did not know how high their flood was. But I thought of it without any active feeling of terror or pain. I was numbed in body and mind. The ceaseless chime of the waves, and the regularity of the rustling play of the pebbles, seemed to lull and soothe me, almost in spite of myself. Cold I was, and in sharp pain, but my mind had not energy enough either for fear or effort. What appeared to me most terrible was the sensation, coming back time after time, of sinking, sinking into the fancied chasm beneath me.

I remember also watching a spray of ivy, far above my head, swaying and waving about in the wind; and a little bird, darting here and there with a brisk flutter of its tiny wings, and a chirping note of satisfaction; and the cloud drifting in soft, small cloudlets across the sky. These things I saw, not as if they were real, but rather as if they were memories of things that had passed before my eyes many years before.

At last—- whether years or hours only had gone by, I could not then have told you—I heard the regular and careful beat of oars upon the water, and presently the grating of a boat's keel upon the shingle, with the rattle of a chain cast out with the grapnel. I could not turn round or raise my head, but I was sure it was Tardif, and that he did not yet see me, for he was whistling softly to himself. I had never heard him whistle before.

"Tardif!" I cried, attempting to shout, but my voice sounded very weak in my own ears, and the other sounds about me seemed very loud. He went on with his unlading, half whistling and half humming his tune, as he landed the nets and creel on the beach.

"Tardif!" I called again, summoning all my strength, and raising my head an inch or two from the hard pebbles which had been its resting-place.

He paused then, and stood quite still, listening. I knew it, though I could not see him. I ran the fingers of my right hand through the loose pebbles about me, and his ear caught the slight noise. In a moment I heard his strong feet coming across them toward me.

"Mon Dieu! mam'zelle," he exclaimed, "what has happened to you?"

I tried to smile as his honest, brown face bent over me, full of alarm. It was so great a relief to see a face like his after that long, weary agony, for it had been agony to me, who did not know what bodily pain was like. But in trying to smile I felt my lips drawn, and my eyes blinded with tears.

"I've fallen down the cliff," I said, feebly, "and I am hurt."

"Mon Dieu!" he cried again. The strong man shook, and his hand trembled as he stooped down and laid it under my head to lift it up a little. His agitation touched me to the heart, even then, and I did my best to speak more calmly.

"Tardif," I whispered, "it is not very much, and I might have been killed. I think my foot is hurt, and I am quite sure my arm is broken."

Speaking made me feel giddy and faint again, so I said no more. He lifted me in his arms as easily and tenderly as a mother lifts up her child, and carried me gently, taking slow and measured strides up the steep slope which led homeward. I closed my eyes, glad to leave myself wholly in his charge, and to have nothing further to dread; yet moaning a little, involuntarily, whenever a fresh pang of pain shot through me. Then he would cry again, "Mon Dieu!" in a beseeching tone, and pause for an instant as if to give me rest. It seemed a long time before we reached the farm-yard gate, and he shouted, with a tremendous voice, to his mother to come and open it. Fortunately she was in sight, and came toward us quickly.

He carried me into the house, and laid me down on the lit de fouaille—a wooden frame forming a sort of couch, and filled with dried fern, which forms the principal piece of furniture in every farm-house kitchen in the Channel Islands. Then he cut away the boot from my swollen ankle, with a steady but careful touch, speaking now and then a word of encouragement, as if I were a child whom he was tending. His mother stood by, looking on helplessly and in bewilderment, for he had not had time to explain my accident to her.

But for my arm, which hung helplessly at my side, and gave me excruciating pain when he touched it, it was quite evident he could do nothing.

"Is there nobody who could set it?" I asked, striving very hard to keep calm.

"We have no doctor in Sark now," he answered. "There is no one but Mother Renouf. I will fetch her."

But when she came she declared herself unable to set a broken limb. They all three held a consultation over it in their own dialect; but I saw by the solemn shaking of their heads, and Tardif's troubled expression, that it was entirely beyond her skill to set it right. She would undertake my sprained ankle, for she was famous for the cure of sprains and bruises, but my arm was past her? The pain I was enduring bathed my face with perspiration, but very little could be done to alleviate it. Tardif's expression grew more and more distressed.

"Mam'zelle knows," he said, stooping down to speak the more softly to me, "there is no doctor nearer than Guernsey, and the night is not far off. What are we to do?"

"Never mind, Tardif," I answered, resolving to be brave; "let the women help me into bed, and perhaps I shall be able to sleep. We must wait till morning."

It was more easily said than done. The two old women did their best, but their touch was clumsy and their help slight, compared to Tardif's. I was thoroughly worn out before I was in bed. But it was a great deal to find myself there, safe and warm, instead of on the cold, hard pebbles on the beach. Mother Renouf put my arm to rest upon a pillow, and bathed and fomented my ankle till it felt much easier.

Never, never shall I forget that night. I could not sleep; but I suppose my mind wandered a little. Hundreds of times I felt myself down on the shore, lying helplessly, while great green waves curled themselves over, and fell just within reach of me, ready to swallow me up, yet always missing me. Then I was back again in my own home in Adelaide, on my father's sheep-farm, and he was still alive, and with no thought but how to make every thing bright and gladsome for me; and hundreds of times I saw the woman who was afterward to be my step-mother, stealing up to the door and trying to get in to him and me. Sometimes I caught myself sobbing aloud, and then Tardif's voice, whispering at the door to ask how mam'zelle was, brought me back to consciousness. Now and then I looked round, fancying I heard my mother's voice speaking to me, and I saw only the wrinkled, yellow face of his mother, nodding drowsily in her seat by the fire. Twice Tardif brought me a cup of tea, freshly made. I could not distinctly made out who he was, or where I was, but I tried to speak loudly enough for him to hear me thank him.

I was very thankful when the first gleam of daylight shone into my room. It seemed to bring clearness to my brain.

"Mam'zelle," said Tardif, coming to my side very early in his fisherman's dress, "I am going to fetch a doctor."

"But it is Sunday," I answered faintly. I knew that no boatman put out to sea willingly on a Sunday from Sark; and the last fatal accident, being on a Sunday, had deepened their reluctance.

"It will be right, mam'zelle," he answered, with glowing eyes. "I have no fear."

"Do not be long away, Tardif," I said, sobbing.

"Not one moment longer than I can help," he replied.

DR. MARTIN DOBRÉE.

My name is Martin Dobrée. Martin or Doctor Martin I was called throughout Guernsey. It will be necessary to state a few particulars about my family and position, before I proceed with my part of this narrative.

My father was Dr. Dobrée. He belonged to one of the oldest families in the island—a family of distinguished pur sang; but our branch of it had been growing poorer instead of richer during the last three or four generations. We had been gravitating steadily downward.

My father lived ostensibly by his profession, but actually upon the income of my cousin, Julia Dobrée, who had been his ward from her childhood. The house we dwelt in, a pleasant one in the Grange, belonged to Julia; and fully half of the year's household expenses were defrayed by her. Our practice, which he and I shared between us, was not a large one, though for its extent it was lucrative enough. But there always is an immense number of medical men in Guernsey in proportion to its population, and the island is healthy. There was small chance for any of us to make a fortune.

Then how was it that I, a young man, still under thirty, was wasting my time, and skill, and professional training, by remaining there, a sort of half pensioner on my cousin's bounty? The thickest rope that holds a vessel, weighing scores of tons, safely to the pier-head is made up of strands so slight that almost a breath will break them.

First, then—and the strength of two-thirds of the strands lay there—was my mother. I could never remember the time when she had not been delicate and ailing, even when I was a rough school-boy at Elizabeth College. It was that infirmity of the body which occasionally betrays the wounds of a soul. I did not comprehend it while I was a boy; then it was headache only. As I grew older I discovered that it was heartache. The gnawing of a perpetual disappointment, worse than a sudden and violent calamity, had slowly eaten away the very foundation of healthy life. No hand could administer any medicine for this disease except mine, and, as soon as I was sure of that, I felt what my first duty was.

I knew where the blame of this lay, if any blame there were. I had found it out years ago by my mother's silence, her white cheeks, and her feeble tone of health. My father was never openly unkind or careless, but there was always visible in his manner a weariness of her, an utter disregard for her feelings. He continued to like young and pretty women, just as he had liked her because she was young and pretty. He remained at the very point he was at when they began their married life. There was nothing patently criminal in it, God forbid!—nothing to create an open and a grave scandal on our little island. But it told upon my mother; it was the one drop of water falling day by day. "A continual dropping in a very rainy day and a contentious woman are alike," says the book of Proverbs. My father's small infidelities were much the same to my mother. She was thrown altogether upon me for sympathy, and support, and love.

When I first fathomed this mystery, my heart rose in very undutiful bitterness against Dr. Dobrée; but by-and-by I found that it resulted less from a want of fidelity to her than from a radical infirmity in his temperament. It was almost as impossible for him to avoid or conceal his preference for younger and more attractive women, as for my mother to conquer the fretting vexation this preference caused to her.

Next to my mother, came Julia, my cousin, five years older than I, who had coldly looked down upon me, and snubbed me like a sister, as a boy; watched my progress through Elizabeth College, and through Guy's Hospital; and perceived at last that I was a young man whom it was no disgrace to call cousin. To crown all, she fell in love with me; so at least my mother told me, taking me into her confidence, and speaking with a depth of pleading in her sunken eyes, which were worn with much weeping. Poor mother! I knew very well what unspoken wish was in her heart. Julia had grown up under her care as I had done, and she stood second to me in her affection.

It is not difficult to love any woman who has a moderate share of attractions—at least I did not find it so then. I was really fond of Julia, too—very fond. I knew her as intimately as any brother knows his sister. She had kept up a correspondence with me all the time I was at Guy's, and her letters had been more interesting and amusing than her conversation generally was. Some women, most cultivated women, can write charming letters; and Julia was a highly-cultivated woman. I came back from Guy's with a very greatly-increased regard and admiration for my cousin Julia.