"Let my son often read and reflect on history: this is the only true philosophy."—Napoleon's last Instructions for the King of Rome.

POST 8VO EDITION, ILLUSTRATED

First Published, December 1901.

Second Edition, revised, March 1902.

Third Edition, revised, January 1903.

Fourth Edition, revised, September 1907.

Reprinted, January 1910.

CROWN 8VO EDITION

First Published, September 1904.

Reprinted, October 1907; July 1910.

DEDICATED TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD ACTON, K.C.V.O., D.C.L., LL.D. REGIUS PROFESSOR OF MODERN HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE, IN ADMIRATION OF HIS PROFOUND HISTORICAL LEARNING, AND IN GRATITUDE FOR ADVICE AND HELP GENEROUSLY GIVEN.

An apology seems to be called for from anyone who gives to the world a new Life of Napoleon I. My excuse must be that for many years I have sought to revise the traditional story of his career in the light of facts gleaned from the British Archives and of the many valuable materials that have recently been published by continental historians. To explain my manner of dealing with these sources would require an elaborate critical Introduction; but, as the limits of my space absolutely preclude any such attempt, I can only briefly refer to the most important topics.

To deal with the published sources first, I would name as of chief importance the works of MM. Aulard, Chuquet, Houssaye, Sorel, and Vandal in France; of Herren Beer, Delbrück, Fournier, Lehmann, Oncken, and Wertheimer in Germany and Austria; and of Baron Lumbroso in Italy. I have also profited largely by the scholarly monographs or collections of documents due to the labours of the "Société d'Histoire Contemporaine," the General Staff of the French Army, of MM. Bouvier, Caudrillier, Capitaine "J.G.," Lévy, Madelin, Sagnac, Sciout, Zivy, and others in France; and of Herren Bailleu, Demelitsch, Hansing, Klinkowstrom, Luckwaldt, Ulmann, and others in Germany. Some of the recently published French Memoirs dealing with those times are not devoid of value, though this class of literature is to be used with caution. The new letters of Napoleon published by M. Léon Lecestre and M. Léonce de Brotonne [pg.VIII] have also opened up fresh vistas into the life of the great man; and the time seems to have come when we may safely revise our judgments on many of its episodes.

But I should not have ventured on this great undertaking, had I not been able to contribute something new to Napoleonic literature. During a study of this period for an earlier work published in the "Cambridge Historical Series," I ascertained the great value of the British records for the years 1795-1815. It is surely discreditable to our historical research that, apart from the fruitful labours of the Navy Records Society, of Messrs. Oscar Browning and Hereford George, and of Mr. Bowman of Toronto, scarcely any English work has appeared that is based on the official records of this period. Yet they are of great interest and value. Our diplomatic agents then had the knack of getting at State secrets in most foreign capitals, even when we were at war with their Governments; and our War Office and Admiralty Records have also yielded me some interesting "finds." M. Lévy, in the preface to his "Napoléon intime" (1893), has well remarked that "the documentary history of the wars of the Empire has not yet been written. To write it accurately, it will be more important thoroughly to know foreign archives than those of France." Those of Russia, Austria, and Prussia have now for the most part been examined; and I think that I may claim to have searched all the important parts of our Foreign Office Archives for the years in question, as well as for part of the St. Helena period. I have striven to embody the results of this search in the present volumes as far as was compatible with limits of space and with the narrative form at which, in my judgment, history ought always to aim.

On the whole, British policy comes out the better the [pg.IX] more fully it is known. Though often feeble and vacillating, it finally attained to firmness and dignity; and Ministers closed the cycle of war with acts of magnanimity towards the French people which are studiously ignored by those who bid us shed tears over the martyrdom of St. Helena. Nevertheless, the splendour of the finale must not blind us to the flaccid eccentricities that made British statesmanship the laughing stock of Europe in 1801-3, 1806-7, and 1809. Indeed, it is questionable whether the renewal of war between England and Napoleon in 1803 was due more to his innate forcefulness or to the contempt which he felt for the Addington Cabinet. When one also remembers our extraordinary blunders in the war of the Third Coalition, it seems a miracle that the British Empire survived that life and death struggle against a man of superhuman genius who was determined to effect its overthrow. I have called special attention to the extent and pertinacity of Napoleon's schemes for the foundation of a French Colonial Empire in India, Egypt, South Africa, and Australia; and there can be no doubt that the events of the years 1803-13 determined, not only the destinies of Europe and Napoleon, but the general trend of the world's colonization.

As it has been necessary to condense the story of Napoleon's life in some parts, I have chosen to treat with special brevity the years 1809-11, which may be called the constans aetas of his career, in order to have more space for the decisive events that followed; but even in these less eventful years I have striven to show how his Continental System was setting at work mighty economic forces that made for his overthrow, so that after the débâcle of 1812 it came to be a struggle of Napoleon and France contra mundum. [pg.X]

While not neglecting the personal details of the great man's life, I have dwelt mainly on his public career. Apart from his brilliant conversations, his private life has few features of abiding interest, perhaps because he early tired of the shallowness of Josephine and the Corsican angularity of his brothers and sisters. But the cause also lay in his own disposition. He once said to M. Gallois: "Je n'aime pas beaucoup les femmes, ni le jeu—enfin rien: je suis tout à fait un être politique." In dealing with him as a warrior and statesman, and in sparing my readers details as to his bolting his food, sleeping at concerts, and indulging in amours where for him there was no glamour of romance, I am laying stress on what interested him most—in a word, I am taking him at his best.

I could not have accomplished this task, even in the present inadequate way, but for the help generously accorded from many quarters. My heartfelt thanks are due to Lord Acton, Regius Professor of Modern History in the University of Cambridge, for advice of the highest importance; to Mr. Hubert Hall of the Public Record Office, for guidance in my researches there; to Baron Lumbroso of Rome, editor of the "Bibliografia ragionata dell' Epoca Napoleonica," for hints on Italian and other affairs; to Dr. Luckwaldt, Privat Docent of the University of Bonn, and author of "Oesterreich und die Anfänge des Befreiungs-Krieges," for his very scholarly revision of the chapters on German affairs; to Mr. F.H.E. Cunliffe, M.A., Fellow of All Souls' College, Oxford, for valuable advice on the campaigns of 1800, 1805, and 1806; to Professor Caudrillier of Grenoble, author of "Pichegru," for information respecting the royalist plot; and to Messrs. J.E. Morris, M.A., and E.L.S. Horsburgh, B.A., for detailed communications concerning Waterloo, [pg.XI] The nieces of the late Professor Westwood of Oxford most kindly allowed the facsimile of the new Napoleon letter, printed opposite p. 156 of vol. i., to be made from the original in their possession; and Miss Lowe courteously placed at my disposal the papers of her father relating to the years 1813-15, as well as to the St. Helena period. I wish here to record my grateful obligations for all these friendly courtesies, which have given value to the book, besides saving me from many of the pitfalls with which the subject abounds. That I have escaped them altogether is not to be imagined; but I can honestly say, in the words of the late Bishop of London, that "I have tried to write true history."

J.H.R.

[NOTE.—The references to Napoleon's "Correspondence" in the notes are to the official French edition, published under the auspices of Napoleon III. The "New Letters of Napoleon" are those edited by Léon Lecestre, and translated into English by Lady Mary Loyd, except in a very few cases where M. Léonce de Brotonne's still more recent edition is cited under his name. By "F.O.," France, No.——, and "F.O.," Prussia, No.——, are meant the volumes of our Foreign Office despatches relating to France and Prussia. For the sake of brevity I have called Napoleon's Marshals and high officials by their names, not by their titles: but a list of these is given at the close of vol. ii.] [pg.XII]

The demand for this work so far exceeded my expectations that I was unable to make any considerable changes in the second edition, issued in March, 1902; and circumstances again make it impossible for me to give the work that thorough recension which I should desire. I have, however, carefully considered the suggestions offered by critics, and have adopted them in some cases. Professor Fournier of Vienna has most kindly furnished me with details which seem to relegate to the domain of legend the famous ice catastrophe at Austerlitz; and I have added a note to this effect on p. 50 of vol. ii. On the other hand, I may justly claim that the publication of Count Balmain's reports relating to St. Helena has served to corroborate, in all important details, my account of Napoleon's captivity.

It only remains to add that I much regret the omission of Mr. Oman's name from II. 12-13 of page viii of the Preface, an omission rendered all the more conspicuous by the appearance of the first volume of his "History of the Peninsular War" in the spring of this year.

J.H.R.

October, 1902.

Notes have been added at the end of ch. v., vol. i.; chs. xxii.,

xxiii., xxviii., xxix., xxxv., vol. ii.; and an Appendix on the

Battle of Waterloo has been added on p. 577, vol. ii.

| CHAPTER | page | ||

| PREFACE | VII | ||

| NOTE ON THE REPUBLICAN CALENDAR | XV | ||

| VOLUME I | |||

| I. PARENTAGE AND EARLY YEARS | 1 | ||

| II. THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND CORSICA | 24 | ||

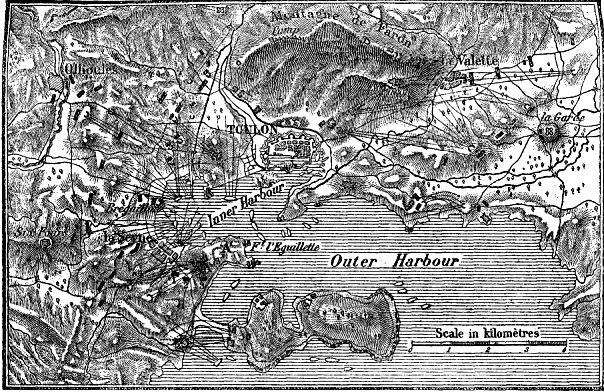

| III. TOULON | 44 | ||

| IV. VENDÉMIAIRE | 57 | ||

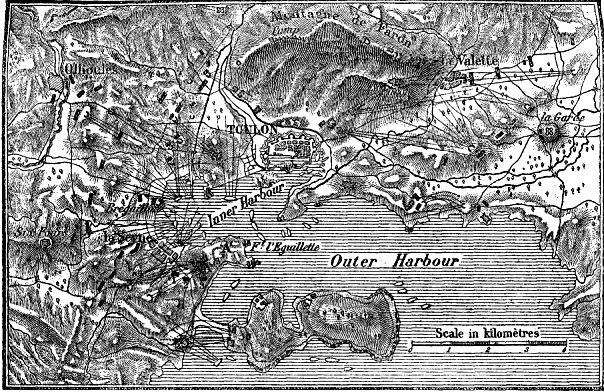

| V. THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN (1796) | 77 | ||

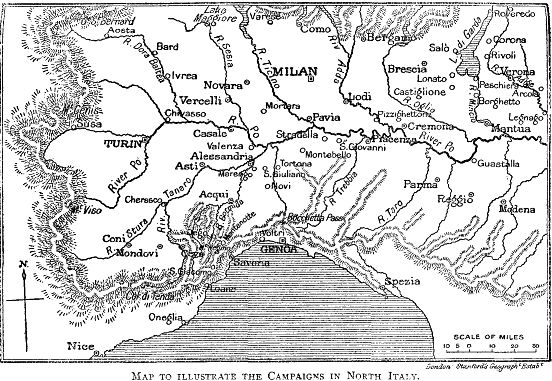

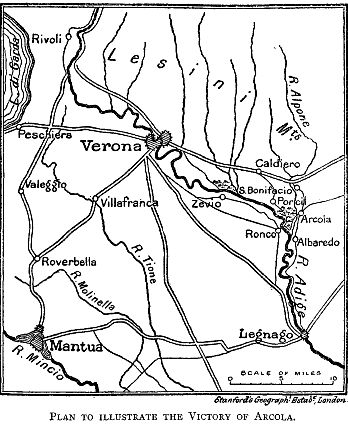

| VI. THE FIGHTS FOR MANTUA | 105 | ||

| VII. LEOBEN TO CAMPO FORMIO | 140 | ||

| VIII. EGYPT | 174 | ||

| IX. SYRIA | 201 | ||

| X. BRUMAIRE | 216 | ||

| XI. MARENGO: LUNÉVILLE | 240 | ||

| XII.THE NEW INSTITUTIONS OF FRANCE | 266 | ||

| XIII. THE CONSULATE FOR LIFE | 302 | ||

| XIV. THE PEACE OF AMIENS | 331 | ||

| XV. A FRENCH COLONIAL EMPIRE: ST. DOMINGO--LOUISIANA--INDIA--AUSTRALIA |

355 | ||

| XVI. NAPOLEON'S INTERVENTIONS | 386 | ||

| XVII. THE RENEWAL OF WAR | 401 | ||

| XVIII. EUROPE AND THE BONAPARTES | 430 | ||

| XIX. THE ROYALIST PLOT | 446 | ||

| XX. THE DAWN OF THE EMPIRE | 465 | ||

| XXI. THE BOULOGNE FLOTILLA | 462 | ||

| XXII. APPENDIX: REPORTS HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED ON (a) THE SALE OF LOUISIANA; (b) THE IRISH DIVISION IN NAPOLEON'S SERVICE |

509 | ||

| ILLUSTRATIONS, MAPS, AND PLANS | |||

| THE SIEGE OF TOULON, 1793 | 51 | ||

| MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE CAMPAIGNS IN NORTH ITALY | 81 | ||

| PLAN TO ILLUSTRATE THE VICTORY OF ARCOLA | 125 | ||

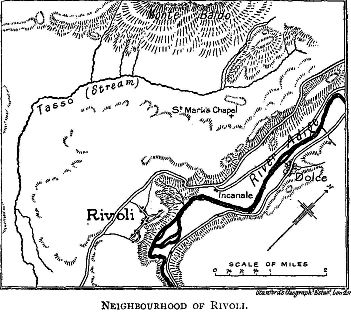

| THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF RIVOLI | 133 | ||

| FACSIMILE OF A LETTER OF NAPOLEON TO "LA CITOYENNE TALLIEN," 1797 | 156 | ||

| CENTRAL EUROPE, after the Peace of Campo Formio, 1797 | 171 | ||

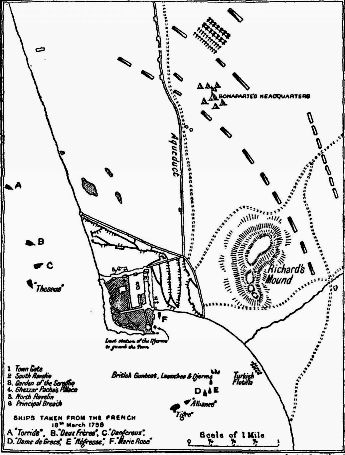

| PLAN OF THE SIEGE OF ACRE, from a contemporary sketch | 205 | ||

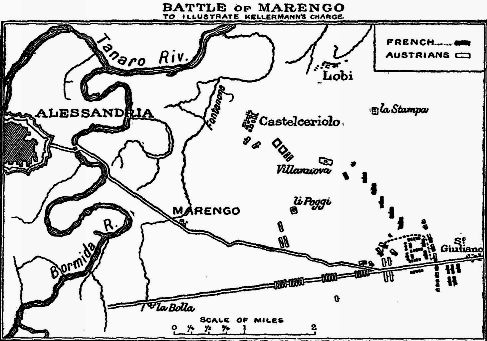

| THE BATTLE OF MARENGO, to illustrate Kellermann's charge | 255 | ||

| FRENCH MAP OF THE SOUTH OF AUSTRALIA, 1807 |

378 | ||

| VOLUME II | |||

| XXII. ULM AND TRAFALGAR | 1 | ||

| XXIII. AUSTERLITZ | 29 | ||

| XXIV. PRUSSIA AND THE NEW CHARLEMAGNE | 51 | ||

| XXV. THE FALL OF PRUSSIA | 79 | ||

| XXVI. THE CONTINENTAL SYSTEM: FRIEDLAND | 103 | ||

| XXVII. TILSIT | 125 | ||

| XXVIII. THE SPANISH RISING | 159 | ||

| XXIX. ERFURT | 174 | ||

| XXX. NAPOLEON AND AUSTRIA | 189 | ||

| XXXI. THE EMPIRE AT ITS HEIGHT | 208 | ||

| XXXII. THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN | 231 | ||

| XXXIII. THE FIRST SAXON CAMPAIGN | 267 | ||

| XXXIV. VITTORIA AND THE ARMISTICE | 300 | ||

| XXXV. DRESDEN AND LEIPZIG | 329 | ||

| XXXVI. FROM THE RHINE TO THE SEINE | 368 | ||

| XXXVII. THE FIRST ABDICATION | 399 | ||

| XXXVIII. ELBA AND PARIS | 435 | ||

| XXXIX. LIGNY AND QUATRE BRAS | 453 | ||

| XL. WATERLOO | 487 | ||

| XLI. FROM THE ELYSÉE TO ST. HELENA | 512 | ||

| XLII. CLOSING YEARS | 539 | ||

| APPENDIX I: LIST OF THE CHIEF APPOINTMENTS AND DIGNITIES BESTOWED BY NAPOLEON |

575 | ||

| APPENDIX II: THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO | 577 | ||

| INDEX | 579 | ||

| MAPS AND PLANS | |||

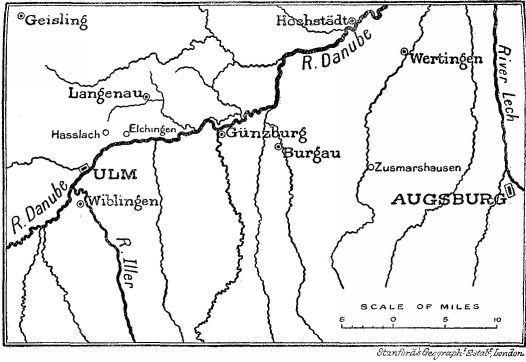

| BATTLE OF ULM | 15 | ||

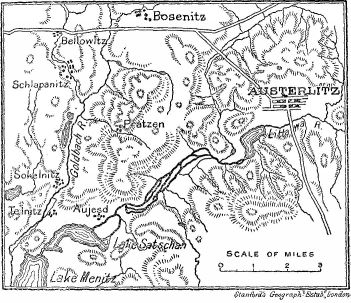

| BATTLE OF AUSTERLITZ | 39 | ||

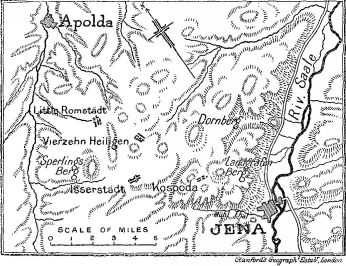

| BATTLE OF JENA | 95 | ||

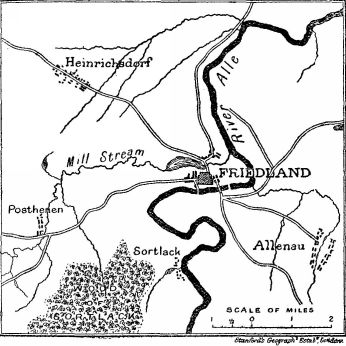

| BATTLE OF FRIEDLAND | 121 | ||

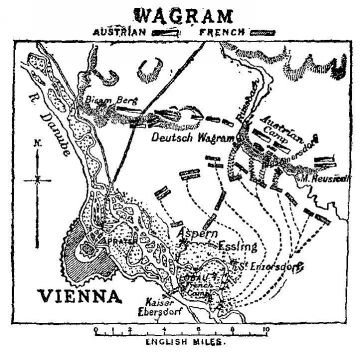

| BATTLE OF WAGRAM | 196 | ||

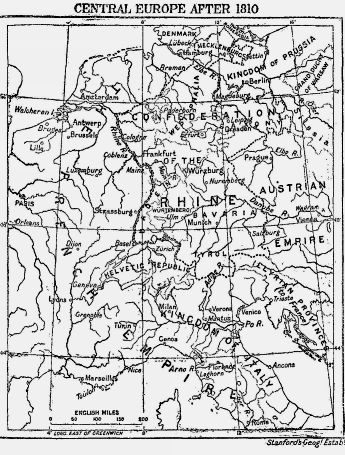

| CENTRAL EUROPE AFTER 1810 | 215 | ||

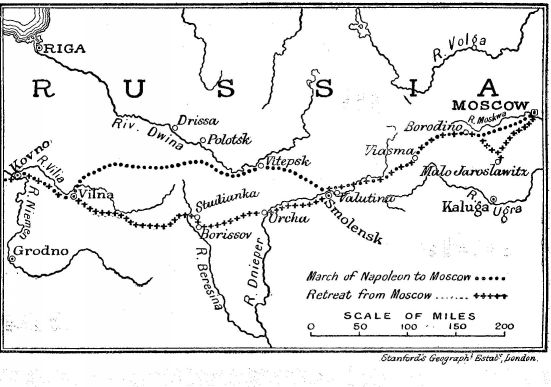

| CAMPAIGN IN RUSSIA | 247 | ||

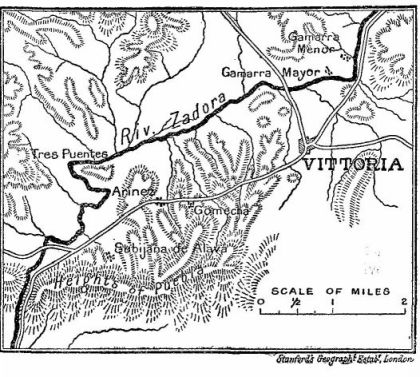

| BATTLE OF VITTORIA | 310 | ||

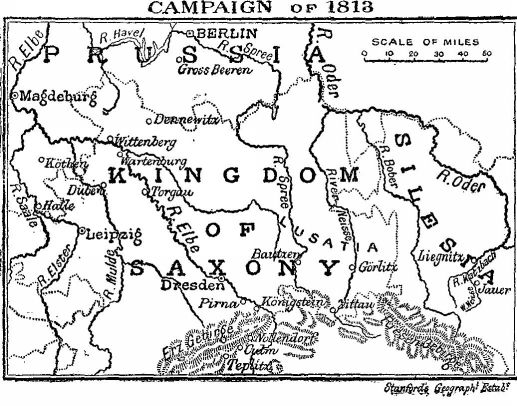

| THE CAMPAIGN OF 1813 | 336 | ||

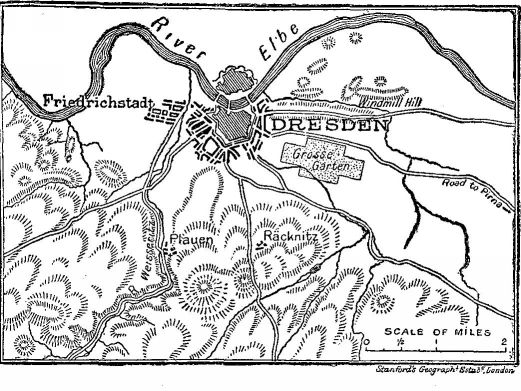

| BATTLE OF DRESDEN | 343 | ||

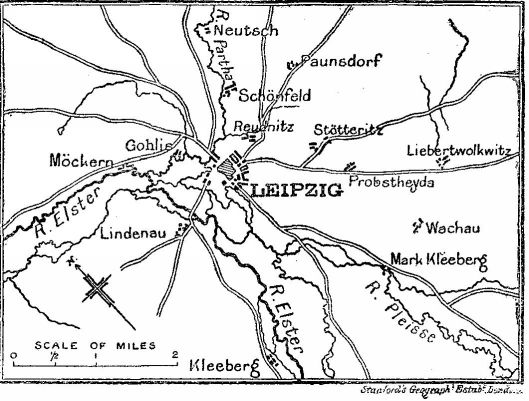

| BATTLE OF LEIPZIG | 357 | ||

| THE CAMPAIGN OF 1814 | to face | 383 | |

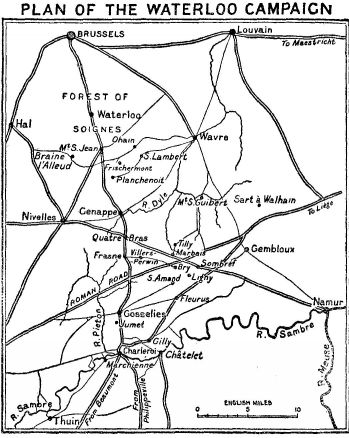

| PLAN OF THE WATERLOO CAMPAIGN | 458 | ||

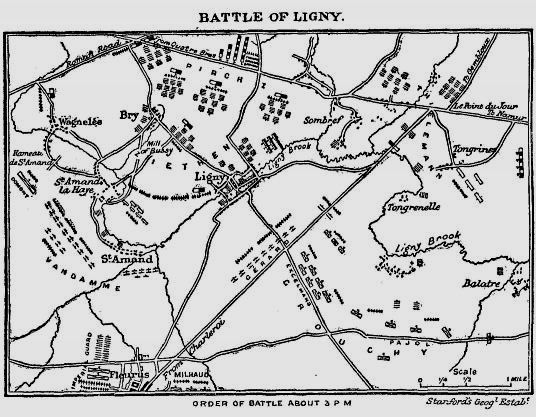

| BATTLE OF LIGNY | 465 | ||

| BATTLE OF WATERLOO, about 11 o'clock a.m. | to face | 490 | |

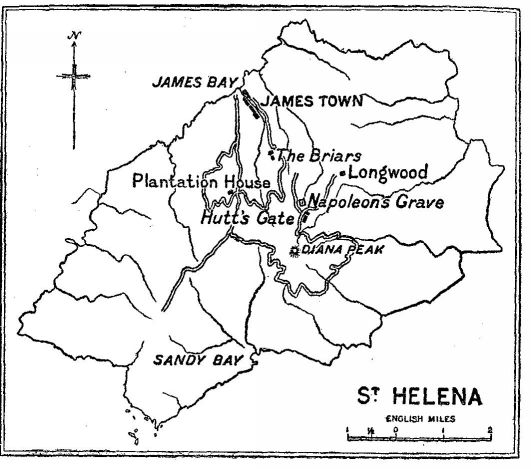

| ST. HELENA | 540 | ||

| FOOTNOTES | |||

| INDEX |

The republican calendar consisted of twelve months of thirty days each, each month being divided into three "decades" of ten days. Five days (in leap years six) were added at the end of the year to bring it into coincidence with the solar year.

An I began Sept. 22, 1792.

" II " " 1793.

" III " " 1794.

" IV (leap year) 1795.

* * * * *

" VIII began Sept. 22, 1799.

" IX " Sept. 23, 1800.

" X " " 1801.

* * * * *

" XIV " " 1805.

The new computation, though reckoned from Sept. 22, 1792, was not introduced until Nov. 26, 1793 (An II). It ceased after Dec. 31, 1805.

The months are as follows:

Vendémiaire Sept. 22 to Oct. 21.

Brumaire Oct. 22 " Nov. 20.

Frimaire Nov. 21 " Dec. 20.

Nivôse Dec. 21 " Jan. 19.

Pluviôse Jan. 20 " Feb. 18.

Ventôse Feb. 19 " Mar. 20.

Germinal Mar. 21 " April 19.

Floréal April 20 " May 19.

Prairial May 20 " June 18.

Messidor June 19 " July 18.

Thermidor July 19 " Aug. 17.

Fructidor Aug. 18 " Sept. 16.

Add five (in leap years six) "Sansculottides" or "Jours complémentaires."

In 1796 (leap year) the numbers in the table of months, so far as concerns all dates between Feb. 28 and Sept. 22, will have to be reduced by one, owing to the intercalation of Feb. 29, which is not compensated for until the end of the republican year.

The matter is further complicated by the fact that the republicans reckoned An VIII as a leap year, though it is not one in the Gregorian Calendar. Hence that year ended on Sept. 22, and An IX and succeeding years began on Sept. 23. Consequently in the above table of months the numbers of all days from Vendémiaire 1, An IX (Sept. 23, 1800), to Nivôse 10, An XIV (Dec. 31, 1805), inclusive, will have to be increased by one, except only in the next leap year between Ventôse 9, An XII, and Vendémiaire 1, An XIII (Feb. 28-Sept, 23, 1804), when the two Revolutionary aberrations happen to neutralize each other. [pg.1]

"I was born when my country was perishing. Thirty thousand French vomited upon our coasts, drowning the throne of Liberty in waves of blood, such was the sight which struck my eyes." This passionate utterance, penned by Napoleon Buonaparte at the beginning of the French Revolution, describes the state of Corsica in his natal year. The words are instinct with the vehemence of the youth and the extravagant sentiment of the age: they strike the keynote of his career. His life was one of strain and stress from his cradle to his grave.

In his temperament as in the circumstances of his time the young Buonaparte was destined for an extraordinary career. Into a tottering civilization he burst with all the masterful force of an Alaric. But he was an Alaric of the south, uniting the untamed strength of his island kindred with the mental powers of his Italian ancestry. In his personality there is a complex blending of force and grace, of animal passion and mental clearness, of northern common sense with the promptings of an oriental imagination; and this union in his nature of seeming opposites explains many of the mysteries of his life. Fortunately for lovers of romance, genius cannot be wholly analyzed, even by the most [pg.2] adroit historical philosophizer or the most exacting champion of heredity. But in so far as the sources of Napoleon's power can be measured, they may be traced to the unexampled needs of mankind in the revolutionary epoch and to his own exceptional endowments. Evidently, then, the characteristics of his family claim some attention from all who would understand the man and the influence which he was to wield over modern Europe.

It has been the fortune of his House to be the subject of dispute from first to last. Some writers have endeavoured to trace its descent back to the Cæsars of Rome, others to the Byzantine Emperors; one genealogical explorer has tracked the family to Majorca, and, altering its name to Bonpart, has discovered its progenitor in the Man of the Iron Mask; while the Duchesse d'Abrantès, voyaging eastwards in quest of its ancestors, has confidently claimed for the family a Greek origin. Painstaking research has dispelled these romancings of historical trouveurs, and has connected this enigmatic stock with a Florentine named "William, who in the year 1261 took the surname of Bonaparte or Buonaparte. The name seems to have been assumed when, amidst the unceasing strifes between Guelfs and Ghibellines that rent the civic life of Florence, William's party, the Ghibellines, for a brief space gained the ascendancy. But perpetuity was not to be found in Florentine politics; and in a short time he was a fugitive at a Tuscan village, Sarzana, beyond the reach of the victorious Guelfs. Here the family seems to have lived for wellnigh three centuries, maintaining its Ghibelline and aristocratic principles with surprising tenacity. The age was not remarkable for the virtue of constancy, or any other virtue. Politics and private life were alike demoralized by unceasing intrigues; and amidst strifes of Pope and Emperor, duchies and republics, cities and autocrats, there was formed that type of Italian character which is delineated in the pages of Macchiavelli. From the depths of debasement of that cynical age the Buonapartes were saved by their poverty, and by the isolation [pg.3] of their life at Sarzana. Yet the embassies discharged at intervals by the more talented members of the family showed that the gifts for intrigue were only dormant; and they were certainly transmitted in their intensity to the greatest scion of the race.

In the year 1529 Francis Buonaparte, whether pressed by poverty or distracted by despair at the misfortunes which then overwhelmed Italy, migrated to Corsica. There the family was grafted upon a tougher branch of the Italian race. To the vulpine characteristics developed under the shadow of the Medici there were now added qualities of a more virile stamp. Though dominated in turn by the masters of the Mediterranean, by Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, by the men of Pisa, and finally by the Genoese Republic, the islanders retained a striking individuality. The rock-bound coast and mountainous interior helped to preserve the essential features of primitive life. Foreign Powers might affect the towns on the sea-board, but they left the clans of the interior comparatively untouched. Their life centred around the family. The Government counted for little or nothing; for was it not the symbol of the detested foreign rule? Its laws were therefore as naught when they conflicted with the unwritten but omnipotent code of family honour. A slight inflicted on a neighbour would call forth the warning words—"Guard thyself: I am on my guard." Forthwith there began a blood feud, a vendetta, which frequently dragged on its dreary course through generations of conspiracy and murder, until, the principals having vanished, the collateral branches of the families were involved. No Corsican was so loathed as the laggard who shrank from avenging the family honour, even on a distant relative of the first offender. The murder of the Duc d'Enghien by Napoleon in 1834 sent a thrill of horror through the Continent. To the Corsicans it seemed little more than an autocratic version of the vendetta traversale[1]. [pg.4]

The vendetta was the chief law of Corsican society up to comparatively recent times; and its effects are still visible in the life of the stern islanders. In his charming romance, "Colomba," M. Prosper Mérimée has depicted the typical Corsican, even of the towns, as preoccupied, gloomy, suspicious, ever on the alert, hovering about his dwelling, like a falcon over his nest, seemingly in preparation for attack or defence. Laughter, the song, the dance, were rarely heard in the streets; for the women, after acting as the drudges of the household, were kept jealously at home, while their lords smoked and watched. If a game at hazard were ventured upon, it ran its course in silence, which not seldom was broken by the shot or the stab—first warning that there had been underhand play. The deed always preceded the word.

In such a life, where commerce and agriculture were despised, where woman was mainly a drudge and man a conspirator, there grew up the typical Corsican temperament, moody and exacting, but withal keen, brave, and constant, which looked on the world as a fencing-school for the glorification of the family and the clan[2]. Of this[pg.5] type Napoleon was to be the supreme exemplar; and the fates granted him as an arena a chaotic France and a distracted Europe.

Amidst that grim Corsican existence the Buonapartes passed their lives during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Occupied as advocates and lawyers with such details of the law as were of any practical importance, they must have been involved in family feuds and the oft-recurring disputes between Corsica and the suzerain Power, Genoa. As became dignitaries in the municipality of Ajaccio, several of the Buonapartes espoused the Genoese side; and the Genoese Senate in a document of the year 1652 styled one of them, Jérome, "Egregius Hieronimus di Buonaparte, procurator Nobilium." These distinctions they seem to have little coveted. Very few families belonged to the Corsican noblesse, and their fiefs were unimportant. In Corsica, as in the Forest Cantons of Switzerland and the Highlands of Scotland, class distinctions were by no means so coveted as in lands that had been thoroughly feudalized; and the Buonapartes, content with their civic dignities at Ajaccio and the attachment of their partisans on their country estates, seem rarely to have used the prefix which implied nobility. Their life was not unlike that of many an old Scottish laird, who, though possibly bourgeois in origin, yet by courtesy ranked as chieftain among his tenants, and was ennobled by the parlance of the countryside, perhaps all the more readily because he refused to wear the honours that came from over the Border.

But a new influence was now to call forth all the powers of this tough stock. In the middle of the eighteenth century we find the head of the family, Charles Marie Buonaparte, aglow with the flame of Corsican patriotism then being kindled by the noble career of Paoli. This gifted patriot, the champion of the islanders, first against the Genoese and later against the French, desired to cement by education the framework of the Corsican Commonwealth and founded a university. It [pg.6] was here that the father of the future French Emperor received a training in law, and a mental stimulus which was to lift his family above the level of the caporali and attorneys with whom its lot had for centuries been cast. His ambition is seen in the endeavour, successfully carried out by his uncle, Lucien, Archdeacon of Ajaccio, to obtain recognition of kinship with the Buonapartes of Tuscany who had been ennobled by the Grand Duke. His patriotism is evinced in his ardent support of Paoli, by whose valour and energy the Genoese were finally driven from the island. Amidst these patriotic triumphs Charles confronted his destiny in the person of Letizia Ramolino, a beautiful girl, descended from an honourable Florentine family which had for centuries been settled in Corsica. The wedding took place in 1764, the bridegroom being then eighteen, and the bride fifteen years of age. The union, if rashly undertaken in the midst of civil strifes, was yet well assorted. Both parties to it were of patrician, if not definitely noble descent, and came of families which combined the intellectual gifts of Tuscany with the vigour of their later island home[3]. From her mother's race, the Pietra Santa family, Letizia imbibed the habits of the most backward and savage part of Corsica, where vendettas were rife and education was almost unknown. Left in ignorance in her early days, she yet was accustomed to hardships, and often showed the fertility of resource which such a life always develops. Hence, at the time of her marriage, she possessed a firmness of will far beyond her years; and her strength and fortitude enabled her to survive the terrible adversities of her early days, as also to meet with quiet matronly dignity the extraordinary honours showered on her as the mother of the French[pg.7] Emperor. She was inured to habits of frugality, which reappeared in the personal tastes of her son. In fact, she so far retained her old parsimonious habits, even amidst the splendours of the French Imperial Court, as to expose herself to the charge of avarice. But there is a touching side to all this. She seems ever to have felt that after the splendour there would come again the old days of adversity, and her instincts were in one sense correct. She lived on to the advanced age of eighty-six, and died twenty-one years after the break-up of her son's empire—a striking proof of the vitality and tenacity of her powers.

A kindly Providence veiled the future from the young couple. Troubles fell swiftly upon them both in private and in public life. Their first two children died in infancy. The third, Joseph, was born in 1768, when the Corsican patriots were making their last successful efforts against their new French oppressors: the fourth, the famous Napoleon, saw the light on August 15th, 1769, when the liberties of Corsica were being finally extinguished. Nine other children were born before the outbreak of the French Revolution reawakened civil strifes, amidst which the then fatherless family was tossed to and fro and finally whirled away to France.

Destiny had already linked the fortunes of the young Napoleon Buonaparte with those of France. After the downfall of Genoese rule in Corsica, France had taken over, for empty promises, the claims of the hard-pressed Italian republic to its troublesome island possession. It was a cheap and practical way of restoring, at least in the Mediterranean the shattered prestige of the French Bourbons. They had previously intervened in Corsican affairs on the side of the Genoese. Yet in 1764 Paoli appealed to Louis XV. for protection. It was granted, in the form of troops that proceeded quietly to occupy the coast towns of the island under cover of friendly assurances. In 1768, before the expiration of an informal truce, Marbeuf, the French commander, [pg.8] commenced hostilities against the patriots[4]. In vain did Rousseau and many other champions of popular liberty protest against this bartering away of insular freedom: in vain did Paoli rouse his compatriots to another and more unequal struggle, and seek to hold the mountainous interior. Poor, badly equipped, rent by family feuds and clan schisms, his followers were no match for the French troops; and after the utter break-up of his forces Paoli fled to England, taking with him three hundred and forty of the most determined patriots. With these irreconcilables Charles Buonaparte did not cast in his lot, but accepted the pardon offered to those who should recognize the French sway. With his wife and their little child Joseph he returned to Ajaccio; and there, shortly afterwards, Napoleon was born. As the patriotic historian, Jacobi, has finely said, "The Corsican people, when exhausted by producing martyrs to the cause of liberty, produced Napoleon Buonaparte[5]."

Seeing that Charles Buonaparte had been an ardent adherent of Paoli, his sudden change of front has exposed him to keen censure. He certainly had not the grit of which heroes are made. His seems to have been an ill-balanced nature, soon buoyed up by enthusiasms,[pg.9] and as speedily depressed by their evaporation; endowed with enough of learning and culture to be a Voltairean and write second-rate verses; and with a talent for intrigue which sufficed to embarrass his never very affluent fortunes. Napoleon certainly derived no world-compelling qualities from his father: for these he was indebted to the wilder strain which ran in his mother's blood. The father doubtless saw in the French connection a chance of worldly advancement and of liberation from pecuniary difficulties; for the new rulers now sought to gain over the patrician families of the island. Many of them had resented the dictatorship of Paoli; and they now gladly accepted the connection with France, which promised to enrich their country and to open up a brilliant career in the French army, where commissions were limited to the scions of nobility.

Much may be said in excuse of Charles Buonaparte's decision, and no one can deny that Corsica has ultimately gained much by her connection with France. But his change of front was open to the charge that it was prompted by self-interest rather than by philosophic foresight. At any rate, his second son throughout his boyhood nursed a deep resentment against his father for his desertion of the patriots' cause. The youth's sympathies were with the peasants, whose allegiance was not to be bought by baubles, whose constancy and bravery long held out against the French in a hopeless guerilla warfare. His hot Corsican blood boiled at the stories of oppression and insult which he heard from his humbler compatriots. When, at eleven years of age, he saw in the military college at Brienne the portrait of Choiseul, the French Minister who had urged on the conquest of Corsica, his passion burst forth in a torrent of imprecations against the traitor; and, even after the death of his father in 1785, he exclaimed that he could never forgive him for not following Paoli into exile.

What trifles seem, at times, to alter the current of human affairs! Had his father acted thus, the young Napoleon would in all probability have entered the [pg.10] military or naval service of Great Britain; he might have shared Paoli's enthusiasm for the land of his adoption, and have followed the Corsican hero in his enterprises against the French Revolution, thenceforth figuring in history merely as a greater Marlborough, crushing the military efforts of democratic France, and luring England into a career of Continental conquest. Monarchy and aristocracy would have gone unchallenged, except within the "natural limits" of France; and the other nations, never shaken to their inmost depths, would have dragged on their old inert fragmentary existence.

The decision of Charles Buonaparte altered the destiny of Europe. He determined that his eldest boy, Joseph, should enter the Church, and that Napoleon should be a soldier. His perception of the characters of his boys was correct. An anecdote, for which the elder brother is responsible, throws a flood of light on their temperaments. The master of their school arranged a mimic combat for his pupils—Romans against Carthaginians. Joseph, as the elder was ranged under the banner of Rome, while Napoleon was told off among the Carthaginians; but, piqued at being chosen for the losing side, the child fretted, begged, and stormed until the less bellicose Joseph agreed to change places with his exacting junior. The incident is prophetic of much in the later history of the family.

Its imperial future was opened up by the deft complaisance now shown by Charles Buonaparte. The reward for his speedy submission to France was soon forthcoming. The French commander in Corsica used his influence to secure the admission of the young Napoleon to the military school of Brienne in Champagne; and as the father was able to satisfy the authorities not only that he was without fortune, but also that his family had been noble for four generations, Napoleon was admitted to this school to be educated at the charges of the King of France (April, 1779). He was now, at the tender age of nine, a stranger in a strange land, among a people whom he detested as the oppressors of his countrymen. [pg.11] Worst of all, he had to endure the taunt of belonging to a subject race. What a position for a proud and exacting child! Little wonder that the official report represented him as silent and obstinate; but, strange to say, it added the word "imperious." It was a tough character which could defy repression amidst such surroundings. As to his studies, little need be said. In his French history he read of the glories of the distant past (when "Germany was part of the French Empire"), the splendours of the reign of Louis XIV., the disasters of France in the Seven Years' War, and the "prodigious conquests of the English in India." But his imagination was kindled from other sources. Boys of pronounced character have always owed far more to their private reading than to their set studies; and the young Buonaparte, while grudgingly learning Latin and French grammar, was feeding his mind on Plutarch's "Lives"—in a French translation. The artful intermingling of the actual and the romantic, the historic and the personal, in those vivid sketches of ancient worthies and heroes, has endeared them to many minds. Rousseau derived unceasing profit from their perusal; and Madame Roland found in them "the pasture of great souls." It was so with the lonely Corsican youth. Holding aloof from his comrades in gloomy isolation, he caught in the exploits of Greeks and Romans a distant echo of the tragic romance of his beloved island home. The librarian of the school asserted that even then the young soldier had modelled his future career on that of the heroes of antiquity; and we may well believe that, in reading of the exploits of Leonidas, Curtius, and Cincinnatus, he saw the figure of his own antique republican hero, Paoli. To fight side by side with Paoli against the French was his constant dream. "Paoli will return," he once exclaimed, "and as soon as I have strength, I will go to help him: and perhaps together we shall be able to shake the odious yoke from off the neck of Corsica."

But there was another work which exercised a great influence on his young mind—the "Gallic War" of [pg.12] Cæsar. To the young Italian the conquest of Gaul by a man of his own race must have been a congenial topic, and in Cæsar himself the future conqueror may dimly have recognized a kindred spirit. The masterful energy and all-conquering will of the old Roman, his keen insight into the heart of a problem, the wide sweep of his mental vision, ranging over the intrigues of the Roman Senate, the shifting politics of a score of tribes, and the myriad administrative details of a great army and a mighty province—these were the qualities that furnished the chief mental training to the young cadet. Indeed, the career of Cæsar was destined to exert a singular fascination over the Napoleonic dynasty, not only on its founder, but also on Napoleon III.; and the change in the character and career of Napoleon the Great may be registered mentally in the effacement of the portraits of Leonidas and Paoli by those of Cæsar and Alexander. Later on, during his sojourn at Ajaccio in 1790, when the first shadows were flitting across his hitherto unclouded love for Paoli, we hear that he spent whole nights poring over Cæsar's history, committing many passages to memory in his passionate admiration of those wondrous exploits. Eagerly he took Cæsar's side as against Pompey, and no less warmly defended him from the charge of plotting against the liberties of the commonwealth[6]. It was a perilous study for a republican youth in whom the military instincts were as ingrained as the genius for rule.

Concerning the young Buonaparte's life at Brienne there exist few authentic records and many questionable anecdotes. Of these last, that which is the most credible and suggestive relates his proposal to his schoolfellows to construct ramparts of snow during the sharp winter of 1783-4. According to his schoolfellow, Bourrienne, these mimic fortifications were planned by Buonaparte, who also directed the methods of attack and defence: or, as others say, he reconstructed the walls according to the needs of modern war. In either case, the incident [pg.13] bespeaks for him great power of organization and control. But there were in general few outlets for his originality and vigour. He seems to have disliked all his comrades, except Bourrienne, as much as they detested him for his moody humours and fierce outbreaks of temper. He is even reported to have vowed that he would do as much harm as possible to the French people; but the remark smacks of the story-book. Equally doubtful are the two letters in which he prays to be removed from the indignities to which he was subjected at Brienne[7]. In other letters which are undoubtedly genuine, he refers to his future career with ardour, and writes not a word as to the bullying to which his Corsican zeal subjected him. Particularly noteworthy is the letter to his uncle begging him to intervene so as to prevent Joseph Buonaparte from taking up a military career. Joseph, writes the younger brother, would make a good garrison officer, as he was well formed and clever at frivolous compliments—"good therefore for society, but for a fight——?"

Napoleon's determination had been noticed by his teachers. They had failed to bend his will, at least on important points. In lesser details his Italian adroitness seems to have been of service; for the officer who inspected the school reported of him: "Constitution, health excellent: character submissive, sweet, honest, grateful: conduct very regular: has always distinguished himself by his application to mathematics: knows history and geography passably: very weak in accomplishments. He will be an excellent seaman: is worthy to enter the School at Paris." To the military school at Paris he was accordingly sent in due course, entering there in October, 1784. The change from the semi-monastic life at Brienne to the splendid edifice which fronts the Champ de Mars had less effect than might[pg.14] have been expected in a youth of fifteen years. Not yet did he become French in sympathy. His love of Corsica and hatred of the French monarchy steeled him against the luxuries of his new surroundings. Perhaps it was an added sting that he was educated at the expense of the monarchy which had conquered his kith and kin. He nevertheless applied himself with energy to his favourite studies, especially mathematics. Defective in languages he still was, and ever remained; for his critical acumen in literature ever fastened on the matter rather than on style. To the end of his days he could never write Italian, much less French, with accuracy; and his tutor at Paris not inaptly described his boyish composition as resembling molten granite. The same qualities of directness and impetuosity were also fatal to his efforts at mastering the movements of the dance. In spite of lessons at Paris and private lessons which he afterwards took at Valence, he was never a dancer: his bent was obviously for the exact sciences rather than the arts, for the geometrical rather than the rhythmical: he thought, as he moved, in straight lines, never in curves.

The death of his father during the year which the youth spent at Paris sharpened his sense of responsibility towards his seven younger brothers and sisters. His own poverty must have inspired him with disgust at the luxury which he saw around him; but there are good reasons for doubting the genuineness of the memorial which he is alleged to have sent from Paris to the second master at Brienne on this subject. The letters of the scholars at Paris were subject to strict surveillance; and, if he had taken the trouble to draw up a list of criticisms on his present training, most assuredly it would have been destroyed. Undoubtedly, however, he would have sympathized with the unknown critic in his complaint of the unsuitableness of sumptuous meals to youths who were destined for the hardships of the camp. At Brienne he had been dubbed "the Spartan," an instance of that almost uncanny faculty of schoolboys [pg.15] to dash off in a nickname the salient features of character. The phrase was correct, almost for Napoleon's whole life. At any rate, the pomp of Paris served but to root his youthful affections more tenaciously in the rocks of Corsica.

In September, 1785, that is, at the age of sixteen, Buonaparte was nominated for a commision as junior lieutenant in La Fère regiment of artillery quartered at Valence on the Rhone. This was his first close contact with real life. The rules of the service required him to spend three months of rigorous drill before he was admitted to his commission. The work was exacting: the pay was small, viz., 1,120 francs, or less than £45, a year; but all reports agree as to his keen zest for his profession and the recognition of his transcendent abilities by his superior officers.[8] There it was that he mastered the rudiments of war, for lack of which many generals of noble birth have quickly closed in disaster careers that began with promise: there, too, he learnt that hardest and best of all lessons, prompt obedience. "To learn obeying is the fundamental art of governing," says Carlyle. It was so with Napoleon: at Valence he served his apprenticeship in the art of conquering and the art of governing.

This spring-time of his life is of interest and importance in many ways: it reveals many amiable qualities, which had hitherto been blighted by the real or fancied scorn of the wealthy cadets. At Valence, while shrinking from his brother officers, he sought society more congenial to his simple tastes and restrained demeanour. In a few of the best bourgeois families of Valence he found happiness. There, too, blossomed the tenderest, purest idyll of his life. At the country house of a cultured lady who had befriended him in his solitude, he saw his first love, Caroline de Colombier. It was a passing fancy; but to her all the passion of his southern nature welled forth. She seems[pg.16] to have returned his love; for in the stormy sunset of his life at St. Helena he recalled some delicious walks at dawn when Caroline and he had—eaten cherries together. One lingers fondly over these scenes of his otherwise stern career, for they reveal his capacity for social joys and for deep and tender affection, had his lot been otherwise cast. How different might have been his life, had France never conquered Corsica, and had the Revolution never burst forth! But Corsica was still his dominant passion. When he was called away from Valence to repress a riot at Lyons, his feelings, distracted for a time by Caroline, swerved back towards his island home; and in September, 1786, he had the joy of revisiting the scenes of his childhood. Warmly though he greeted his mother, brothers and sisters, after an absence of nearly eight years, his chief delight was in the rocky shores, the verdant dales and mountain heights of Corsica. The odour of the forests, the setting of the sun in the sea "as in the bosom of the infinite," the quiet proud independence of the mountaineers themselves, all enchanted him. His delight reveals almost Wertherian powers of "sensibility." Even the family troubles could not damp his ardour. His father had embarked on questionable speculations, which now threatened the Buonapartes with bankruptcy, unless the French Government proved to be complacent and generous. With the hope of pressing one of the family claims on the royal exchequer, the second son procured an extension of furlough and sped to Paris. There at the close of 1787 he spent several weeks, hopefully endeavouring to extract money from the bankrupt Government. It was a season of disillusionment in more senses than one; for there he saw for himself the seamy side of Parisian life, and drifted for a brief space about the giddy vortex of the Palais Royal. What a contrast to the limpid life of Corsica was that turbid frothy existence—already swirling towards its mighty plunge!

After a furlough of twenty-one months he rejoined his regiment, now at Auxonne. There his health suffered [pg.17] considerably, not only from the miasma of the marshes of the river Saône, but also from family anxieties and arduous literary toils. To these last it is now needful to refer. Indeed, the external events of his early life are of value only as they reveal the many-sidedness of his nature and the growth of his mental powers.

How came he to outgrow the insular patriotism of his early years? The foregoing recital of facts must have already suggested one obvious explanation. Nature had dowered him so prodigally with diverse gifts, mainly of an imperious order, that he could scarcely have limited his sphere of action to Corsica. Profoundly as he loved his island, it offered no sphere commensurate with his varied powers and masterful will. It was no empty vaunt which his father had uttered on his deathbed that his Napoleon would one day overthrow the old monarchies and conquer Europe.[9] Neither did the great commander himself overstate the peculiarity of his temperament, when he confessed that his instincts had ever prompted him that his will must prevail, and that what pleased him must of necessity belong to him. Most spoilt children harbour the same illusion, for a brief space. But all the buffetings of fortune failed to drive it from the young Buonaparte; and when despair as to his future might have impaired the vigour of his domineering instincts, his mind and will acquired a fresh rigidity by coming under the spell of that philosophizing doctrinaire, Rousseau.

There was every reason why he should early be attracted by this fantastic thinker. In that notable work, "Le Contrat Social" (1762), Rousseau called attention to the antique energy shown by the Corsicans in defence of their liberties, and in a startlingly prophetic phrase he exclaimed that the little island would one day astonish Europe. The source of this predilection of Rousseau for Corsica is patent. Born and reared at Geneva, he felt a Switzer's love for a people which was[pg.18] "neither rich nor poor but self-sufficing "; and in the simple life and fierce love of liberty of the hardy islanders he saw traces of that social contract which he postulated as the basis of society. According to him, the beginnings of all social and political institutions are to be found in some agreement or contract between men. Thus arise the clan, the tribe, the nation. The nation may delegate many of its powers to a ruler; but if he abuse such powers, the contract between him and his people is at an end, and they may return to the primitive state, which is founded on an agreement of equals with equals. Herein lay the attractiveness of Rousseau for all who were discontented with their surroundings. He seemed infallibly to demonstrate the absurdity of tyranny and the need of returning to the primitive bliss of the social contract. It mattered not that the said contract was utterly unhistorical and that his argument teemed with fallacies. He inspired a whole generation with detestation of the present and with longings for the golden age. Poets had sung of it, but Rousseau seemed to bring it within the grasp of long-suffering mortals.

The first extant manuscript of Napoleon, written at Valence in April, 1786, shows that he sought in Rousseau's armoury the logical weapons for demonstrating the "right" of the Corsicans to rebel against the French. The young hero-worshipper begins by noting that it is the birthday of Paoli. He plunges into a panegyric on the Corsican patriots, when he is arrested by the thought that many censure them for rebelling at all. "The divine laws forbid revolt. But what have divine laws to do with a purely human affair? Just think of the absurdity—divine laws universally forbidding the casting off of a usurping yoke!... As for human laws, there cannot be any after the prince violates them." He then postulates two origins for government as alone possible. Either the people has established laws and submitted itself to the prince, or the prince has established laws. In the first case, the prince is engaged by the very nature of his office to execute the covenants. In the second [pg.19] case, the laws tend, or do not tend, to the welfare of the people, which is the aim of all government: if they do not, the contract with the prince dissolves of itself, for the people then enters again into its primitive state. Having thus proved the sovereignty of the people, Buonaparte uses his doctrine to justify Corsican revolt against France, and thus concludes his curious medley: "The Corsicans, following all the laws of justice, have been able to shake off the yoke of the Genoese, and may do the same with that of the French. Amen."

Five days later he again gives the reins to his melancholy. "Always alone, though in the midst of men," he faces the thought of suicide. With an innate power of summarizing and balancing thoughts and sensations, he draws up arguments for and against this act. He is in the dawn of his days and in four months' time he will see "la patrie," which he has not seen since childhood. What joy! And yet—how men have fallen away from nature: how cringing are his compatriots to their conquerors: they are no longer the enemies of tyrants, of luxury, of vile courtiers: the French have corrupted their morals, and when "la patrie" no longer survives, a good patriot ought to die. Life among the French is odious: their modes of life differ from his as much as the light of the moon differs from that of the sun.—A strange effusion this for a youth of seventeen living amidst the full glories of the spring in Dauphiné. It was only a few weeks before the ripening of cherries. Did that cherry-idyll with Mdlle. de Colombier lure him back to life? Or did the hope of striking a blow for Corsica stay his suicidal hand? Probably the latter; for we find him shortly afterwards tilting against a Protestant minister of Geneva who had ventured to criticise one of the dogmas of Rousseau's evangel.

The Genevan philosopher had asserted that Christianity, by enthroning in the hearts of Christians the idea of a Kingdom not of this world, broke the unity of civil society, because it detached the hearts of its converts from the State, as from all earthly things. To this the [pg.20] Genevan minister had successfully replied by quoting Christian teachings on the subject at issue. But Buonaparte fiercely accuses the pastor of neither having understood, nor even read, "Le Contrat Social": he hurls at his opponent texts of Scripture which enjoin obedience to the laws: he accuses Christianity of rendering men slaves to an anti-social tyranny, because its priests set up an authority in opposition to civil laws; and as for Protestantism, it propagated discords between its followers, and thereby violated civic unity. Christianity, he argues, is a foe to civil government, for it aims at making men happy in this life by inspiring them with hope of a future life; while the aim of civil government is "to lend assistance to the feeble against the strong, and by this means to allow everyone to enjoy a sweet tranquillity, the road of happiness." He therefore concludes that Christianity and civil government are diametrically opposed.

In this tirade we see the youth's spirit of revolt flinging him not only against French law, but against the religion which sanctions it. He sees none of the beauty of the Gospels which Rousseau had admitted. His views are more rigid than those of his teacher. Scarcely can he conceive of two influences, the spiritual and the governmental, working on parallel lines, on different parts of man's nature. His conception of human society is that of an indivisible, indistinguishable whole, wherein materialism, tinged now and again by religious sentiment and personal honour, is the sole noteworthy influence. He finds no worth in a religion which seeks to work from within to without, which aims at transforming character, and thus transforming the world. In its headlong quest of tangible results his eager spirit scorns so tardy a method: he will "compel men to be happy," and for this result there is but one practicable means, the Social Contract, the State. Everything which mars the unity of the Social Contract shall be shattered, so that the State may have a clear field for the exercise of its beneficent despotism. Such is Buonaparte's political and religious creed at the age of seventeen, and such it [pg.21] remained (with many reservations suggested by maturer thought and self-interest) to the end of his days. It reappears in his policy anent the Concordat of 18222, by which religion was reduced to the level of handmaid to the State, as also in his frequent assertions that he would never have quite the same power as the Czar and the Sultan, because he had not undivided sway over the consciences of his people.[10] In this boyish essay we may perhaps discern the fundamental reason of his later failures. He never completely understood religion, or the enthusiasm which it can evoke; neither did he ever fully realize the complexity of human nature, the many-sidedness of social life, and the limitations that beset the action even of the most intelligent law-maker.[11]

His reading of Rousseau having equipped him for the[pg.22] study of human society and government, he now, during his first sojourn at Auxonne (June, 1788—September, 1789), proceeds to ransack the records of the ancient and modern world. Despite ill-health, family troubles, and the outbreak of the French Revolution, he grapples with this portentous task. The history, geography, religion, and social customs of the ancient Persians, Scythians, Thracians, Athenians, Spartans, Egyptians, and Carthaginians—all furnished materials for his encyclopædic note-books. Nothing came amiss to his summarizing genius. Here it was that he gained that knowledge of the past which was to astonish his contemporaries. Side by side with suggestions on regimental discipline and improvements in artillery, we find notes on the opening episodes of Plato's "Republic," and a systematic summary of English history from the earliest times down to the Revolution of 1688. This last event inspired him with special interest, because the Whigs and their philosophic champion, Locke, maintained that James II. had violated the original contract between prince and people. Everywhere in his notes Napoleon emphasizes the incidents which led to conflicts between dynasties or between rival principles. In fact, through all these voracious studies there appear signs of his determination to write a history of Corsica; and, while inspiriting his kinsmen by recalling the glorious past, he sought to weaken the French monarchy by inditing a "Dissertation sur l'Autorité Royale." His first sketch of this work runs as follows:

"23 October, 1788. Auxonne.

"This work will begin with general ideas as to the origin and the enhanced prestige of the name of king. Military rule is favourable to it: this work will afterwards enter into the details of the usurped authority enjoyed by the Kings of the twelve Kingdoms of Europe.

"There are very few Kings who have not deserved dethronement[12]."

This curt pronouncement is all that remains of the[pg.23] projected work. It sufficiently indicates, however, the aim of Napoleon's studies. One and all they were designed to equip him for the great task of re-awakening the spirit of the Corsicans and of sapping the base of the French monarchy.

But these reams of manuscript notes and crude literary efforts have an even wider source of interest. They show how narrow was his outlook on life. It all turned on the regeneration of Corsica by methods which he himself prescribed. We are therefore able to understand why, when his own methods of salvation for Corsica were rejected, he tore himself away and threw his undivided energies into the Revolution.

Yet the records of his early life show that in his character there was a strain of true sentiment and affection. In him Nature carved out a character of rock-like firmness, but she adorned it with flowers of human sympathy and tendrils of family love. At his first parting from his brother Joseph at Autun, when the elder brother was weeping passionately, the little Napoleon dropped a tear: but that, said the tutor, meant as much as the flood of tears from Joseph. Love of his relatives was a potent factor of his policy in later life; and slander has never been able wholly to blacken the character of a man who loved and honoured his mother, who asserted that her advice had often been of the highest service to him, and that her justice and firmness of spirit marked her out as a natural ruler of men. But when these admissions are freely granted, it still remains true that his character was naturally hard; that his sense of personal superiority made him, even as a child, exacting and domineering; and the sequel was to show that even the strongest passion of his youth, his determination to free Corsica from France, could be abjured if occasion demanded, all the force of his nature being thenceforth concentrated on vaster adventures. [pg.24]

"They seek to destroy the Revolution by attacking my person: I will defend it, for I am the Revolution." Such were the words uttered by Buonaparte after the failure of the royalist plot of 1804. They are a daring transcript of Louis XIV.'s "L'état, c'est moi." That was a bold claim, even for an age attuned to the whims of autocrats: but this of the young Corsican is even more daring, for he thereby equated himself with a movement which claimed to be wide as humanity and infinite as truth. And yet when he spoke these words, they were not scouted as presumptuous folly: to most Frenchmen they seemed sober truth and practical good sense. How came it, one asks in wonder, that after the short space of fifteen years a world-wide movement depended on a single life, that the infinitudes of 1789 lived on only in the form, and by the pleasure, of the First Consul? Here surely is a political incarnation unparalleled in the whole course of human history. The riddle cannot be solved by history alone. It belongs in part to the domain of psychology, when that science shall undertake the study, not merely of man as a unit, but of the aspirations, moods, and whims of communities and nations. Meanwhile it will be our far humbler task to strive to point out the relation of Buonaparte to the Revolution, and to show how the mighty force of his will dragged it to earth.

The first questions that confront us are obviously these. Were the lofty aims and aspirations of the [pg.25] Revolution attainable? And, if so, did the men of 1789 follow them by practical methods? To the former of these questions the present chapter will, in part at least, serve as an answer. On the latter part of the problem the events described in later chapters will throw some light: in them we shall see that the great popular upheaval let loose mighty forces that bore Buonaparte on to fortune.

Here we may notice that the Revolution was not a simple and therefore solid movement. It was complex and contained the seeds of discord which lurk in many-sided and militant creeds. The theories of its intellectual champions were as diverse as the motives which spurred on their followers to the attack on the outworn abuses of the age.

Discontent and faith were the ultimate motive powers of the Revolution. Faith prepared the Revolution and discontent accomplished it. Idealists who, in varied planes of thought, preached the doctrine of human perfectibility, succeeded in slowly permeating the dull toiling masses of France with hope. Omitting here any notice of philosophic speculation as such, we may briefly notice the teachings of three writers whose influence on revolutionary politics was to be definite and practical. These were Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau. The first was by no means a revolutionist, for he decided in favour of a mixed form of government, like that of England, which guaranteed the State against the dangers of autocracy, oligarchy, and mob-rule. Only by a ricochet did he assail the French monarchy. But he re-awakened critical inquiry; and any inquiry was certain to sap the base of the ancien régime in France. Montesquieu's teaching inspired the group of moderate reformers who in 1789 desired to re-fashion the institutions of France on the model of those of England. But popular sentiment speedily swept past these Anglophils towards the more attractive aims set forth by Voltaire.

This keen thinker subjected the privileged classes, especially the titled clergy, to a searching fire of [pg.26] philosophic bombs and barbed witticisms. Never was there a more dazzling succession of literary triumphs over a tottering system. The satirized classes winced and laughed, and the intellect of France was conquered, for the Revolution. Thenceforth it was impossible that peasants who were nominally free should toil to satisfy the exacting needs of the State, and to support the brilliant bevy of nobles who flitted gaily round the monarch at Versailles. The young King Louis XVI., it is true, carried through several reforms, but he had not enough strength of will to abolish the absurd immunities from taxation which freed the nobles and titled clergy from the burdens of the State. Thus, down to 1789, the middle classes and peasants bore nearly all the weight of taxation, while the peasants were also encumbered by feudal dues and tolls. These were the crying grievances which united in a solid phalanx both thinkers and practical men, and thereby gave an immense impetus to the levelling doctrines of Rousseau.

Two only of his political teachings concern us here, namely, social equality and the unquestioned supremacy of the State; for to these dogmas, when they seemed doomed to political bankruptcy, Napoleon Buonaparte was to act as residuary legatee. According to Rousseau, society and government originated in a social contract, whereby all members of the community have equal rights. It matters not that the spirit of the contract may have evaporated amidst the miasma of luxury. That is a violation of civil society; and members are justified in reverting at once to the primitive ideal. If the existence of the body politic be endangered, force may be used: "Whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be constrained to do so by the whole body; which means nothing else than that he shall be forced to be free." Equally plausible and dangerous was his teaching as to the indivisibility of the general will. Deriving every public power from his social contract, he finds it easy to prove that the sovereign power, [pg.27] vested in all the citizens, must be incorruptible, inalienable, unrepresentable, indivisible, and indestructible. Englishmen may now find it difficult to understand the enthusiasm called forth by this quintessence of negations; but to Frenchman recently escaped from the age of privilege and warring against the coalition of kings, the cry of the Republic one and indivisible was a trumpet call to death or victory. Any shifts, even that of a dictatorship, were to be borne, provided that social equality could be saved. As republican Rome had saved her early liberties by intrusting unlimited powers to a temporary dictator, so, claimed Rousseau, a young commonwealth must by a similar device consult Nature's first law of self-preservation. The dictator saves liberty by temporarily abrogating it: by momentary gagging of the legislative power he renders it truly vocal.

The events of the French Revolution form a tragic commentary on these theories. In the first stage of that great movement we see the followers of Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau marching in an undivided host against the ramparts of privilege. The walls of the Bastille fall down even at the blast of their trumpets. Odious feudal privileges disappear in a single sitting of the National Assembly; and the Parlements, or supreme law courts of the provinces, are swept away. The old provinces themselves are abolished, and at the beginning of 1790 France gains social and political unity by her new system of Departments, which grants full freedom of action in local affairs, though in all national concerns it binds France closely to the new popular government at Paris. But discords soon begin to divide the reformers: hatred of clerical privilege and the desire to fill the empty coffers of the State dictate the first acts of spoliation. Tithes are abolished: the lands of the Church are confiscated to the service of the State; monastic orders are suppressed; and the Government undertakes to pay the stipends of bishops and priests. Furthermore, their subjection to the State is definitely secured by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (July, [pg.28] 1790) which invalidates their allegiance to the Pope. Most of the clergy refuse: these are termed non-jurors or orthodox priests, while their more complaisant colleagues are known as constitutional priests. Hence arises a serious schism in the Church, which distracts the religious life of the land, and separates the friends of liberty from the champions of the rigorous equality preached by Rousseau.

The new constitution of 1791 was also a source of discord. In its jealousy of the royal authority, the National Assembly seized very many of the executive functions of government. The results were disastrous. Laws remained without force, taxes went uncollected, the army was distracted by mutinies, and the monarchy sank slowly into the gulf of bankruptcy and anarchy. Thus, in the course of three years, the revolutionists goaded the clergy to desperation, they were about to overthrow the monarchy, every month was proving their local self-government to be unworkable, and they themselves split into factions that plunged France into war and drenched her soil by organized massacres.

We know very little about the impression made on the young Buonaparte by the first events of the Revolution. His note-book seems even to show that he regarded them as an inconvenient interference with his plans for Corsica. But gradually the Revolution excites his interest. In September, 1789, we find him on furlough in Corsica sharing the hopes of the islanders that their representatives in the French National Assembly will obtain the boon of independence. He exhorts his compatriots to favour the democratic cause, which promises a speedy deliverance from official abuses. He urges them to don the new tricolour cockade, symbol of Parisian triumph over the old monarchy; to form a club; above all, to organize a National Guard. The young officer knew that military power was passing from the royal army, now honeycombed with discontent, to the National Guard. Here surely was Corsica's means of [pg.29] salvation. But the French governor of Corsica intervenes. The club is closed, and the National Guard is dispersed. Thereupon Buonaparte launches a vigorous protest against the tyranny of the governor and appeals to the National Assembly of France for some guarantee of civil liberty. His name is at the head of this petition, a sufficiently daring step for a junior lieutenant on furlough. But his patriotism and audacity carry him still further. He journeys to Bastia, the official capital of his island, and is concerned in an affray between the populace and the royal troops (November 5th, 1789). The French authorities, fortunately for him, are nearly powerless: he is merely requested to return to Ajaccio; and there he organizes anew the civic force, and sets the dissident islanders an example of good discipline by mounting guard outside the house of a personal opponent.

Other events now transpired which began to assuage his opposition to France. Thanks to the eloquent efforts of Mirabeau, the Corsican patriots who had remained in exile since 1768 were allowed to return and enjoy the full rights of citizenship. Little could the friends of liberty at Paris, or even the statesman himself, have foreseen all the consequences of this action: it softened the feelings of many Corsicans towards their conquerors; above all, it caused the heart of Napoleon Buonaparte for the first time to throb in accord with that of the French nation. His feelings towards Paoli also began to cool. The conduct of this illustrious exile exposed him to the charge of ingratitude towards France. The decree of the French National Assembly, which restored him to Corsican citizenship, was graced by acts of courtesy such as the generous French nature can so winningly dispense. Louis XVI. and the National Assembly warmly greeted him, and recognized him as head of the National Guard of the island. Yet, amidst all the congratulations, Paoli saw the approach of anarchy, and behaved with some reserve. Outwardly, however, concord seemed to be assured, when on July 14th, 1790, he landed in Corsica; but the hatred long [pg.30] nursed by the mountaineers and fisherfolk against France was not to be exorcised by a few demonstrations. In truth, the island was deeply agitated. The priests were rousing the people against the newly decreed Civil Constitution of the Clergy; and one of these disturbances endangered the life of Napoleon himself. He and his brother Joseph chanced to pass by when one of the processions of priests and devotees was exciting the pity and indignation of the townsfolk. The two brothers, who were now well known as partisans of the Revolution, were threatened with violence, and were saved only by their own firm demeanour and the intervention of peacemakers.

Then again, the concession of local self-government to the island, as one of the Departments of France, revealed unexpected difficulties. Bastia and Ajaccio struggled hard for the honour of being the official capital. Paoli favoured the claims of Bastia, thereby annoying the champions of Ajaccio, among whom the Buonapartes were prominent. The schism was widened by the dictatorial tone of Paoli, a demeanour which ill became the chief of a civic force. In fact, it soon became apparent that Corsica was too small a sphere for natures so able and masterful as those of Paoli and Napoleon Buonaparte.

The first meeting of these two men must have been a scene of deep interest. It was on the fatal field of Ponte Nuovo. Napoleon doubtless came there in the spirit of true hero-worship. But hero-worship which can stand the strain of actual converse is rare indeed, especially when the expectant devotee is endowed with keen insight and habits of trenchant expression. One phrase has come down to us as a result of the interview; but this phrase contains a volume of meaning. After Paoli had explained the disposition of his troops against the French at Ponte Nuovo, Buonaparte drily remarked to his brother Joseph, "The result of these dispositions was what was inevitable."[13][pg.31]

For the present, Buonaparte and other Corsican democrats were closely concerned with the delinquencies of the Comte de Buttafuoco, the deputy for the twelve nobles of the island to the National Assembly of France. In a letter written on January 23rd, 1791, Buonaparte overwhelms this man with a torrent of invective.—He it was who had betrayed his country to France in 1768. Self-interest and that alone prompted his action then, and always. French rule was a cloak for his design of subjecting Corsica to "the absurd feudal régime" of the barons. In his selfish royalism he had protested against the new French constitution as being unsuited to Corsica, "though it was exactly the same as that which brought us so much good and was wrested from us only amidst streams of blood."—The letter is remarkable for the southern intensity of its passion, and for a certain hardening of tone towards Paoli. Buonaparte writes of Paoli as having been ever "surrounded by enthusiasts, and as failing to understand in a man any other passion than fanaticism for liberty and independence," and as duped by Buttafuoco in 1768.[14] The phrase has an obvious reference to the Paoli of 1791, surrounded by men who had shared his long exile and regarded the English constitution as their model. Buonaparte, on the contrary, is the accredited champion of French democracy, his furious epistle being printed by the Jacobin Club of Ajaccio. [pg.32]

After firing off this tirade Buonaparte returned to his regiment at Auxonne (February, 1791). It was high time; for his furlough, though prolonged on the plea of ill-health, had expired in the preceding October, and he was therefore liable to six months' imprisonment. But the young officer rightly gauged the weakness of the moribund monarchy; and the officers of his almost mutinous regiment were glad to get him back on any terms. Everywhere in his journey through Provence and Dauphiné, Buonaparte saw the triumph of revolutionary principles. He notes that the peasants are to a man for the Revolution; so are the rank and file of the regiment. The officers are aristocrats, along with three-fourths of those who belong to "good society": so are all the women, for "Liberty is fairer than they, and eclipses them." The Revolution was evidently gaining completer hold over his mind and was somewhat blurring his insular sentiments, when a rebuff from Paoli further weakened his ties to Corsica. Buonaparte had dedicated to him his work on Corsica, and had sent him the manuscript for his approval. After keeping it an unconscionable time, the old man now coldly replied that he did not desire the honour of Buonaparte's panegyric, though he thanked him heartily for it; that the consciousness of having done his duty sufficed for him in his old age; and, for the rest, history should not be written in youth. A further request from Joseph Buonaparte for the return of the slighted manuscript brought the answer that he, Paoli, had no time to search his papers. After this, how could hero-worship subsist?

The four months spent by Buonaparte at Auxonne were, indeed, a time of disappointment and hardship. Out of his slender funds he paid for the education of his younger brother, Louis, who shared his otherwise desolate lodging. A room almost bare but for a curtainless bed, a table heaped with books and papers, and two chairs—such were the surroundings of the lieutenant in the spring of 1791. He lived on bread that he might rear his brother for the army, and that he might buy [pg.33] books, overjoyed when his savings mounted to the price of some coveted volume.

Perhaps the depressing conditions of his life at Auxonne may account for the acrid tone of an essay which he there wrote in competition for a prize offered by the Academy of Lyons on the subject—"What truths and sentiments ought to be inculcated to men for their happiness." It was unsuccessful; and modern readers will agree with the verdict of one of the judges that it was incongruous in arrangement and of a bad and ragged style. The thoughts are set forth in jerky, vehement clauses; and, in place of the sensibilité of some of his earlier effusions, we feel here the icy breath of materialism. He regards an ideal human society as a geometrical structure based on certain well-defined postulates. All men ought to be able to satisfy certain elementary needs of their nature; but all that is beyond is questionable or harmful. The ideal legislator will curtail wealth so as to restore the wealthy to their true nature—and so forth. Of any generous outlook on the wider possibilities of human life there is scarcely a trace. His essay is the apotheosis of social mediocrity. By Procrustean methods he would have forced mankind back to the dull levels of Sparta: the opalescent glow of Athenian life was beyond his ken. But perhaps the most curious passage is that in which he preaches against the sin and folly of ambition. He pictures Ambition as a figure with pallid cheeks, wild eyes, hasty step, jerky movements and sardonic smile, for whom crimes are a sport, while lies and calumnies are merely arguments and figures of speech. Then, in words that recall Juvenal's satire on Hannibal's career, he continues: "What is Alexander doing when he rushes from Thebes into Persia and thence into India? He is ever restless, he loses his wits, he believes himself God. What is the end of Cromwell? He governs England. But is he not tormented by all the daggers of the furies?"—The words ring false, even for this period of Buonaparte's life; and one can readily [pg.34] understand his keen wish in later years to burn every copy of these youthful essays. But they have nearly all survived; and the diatribe against ambition itself supplies the feather wherewith history may wing her shaft at the towering flight of the imperial eagle.[15]