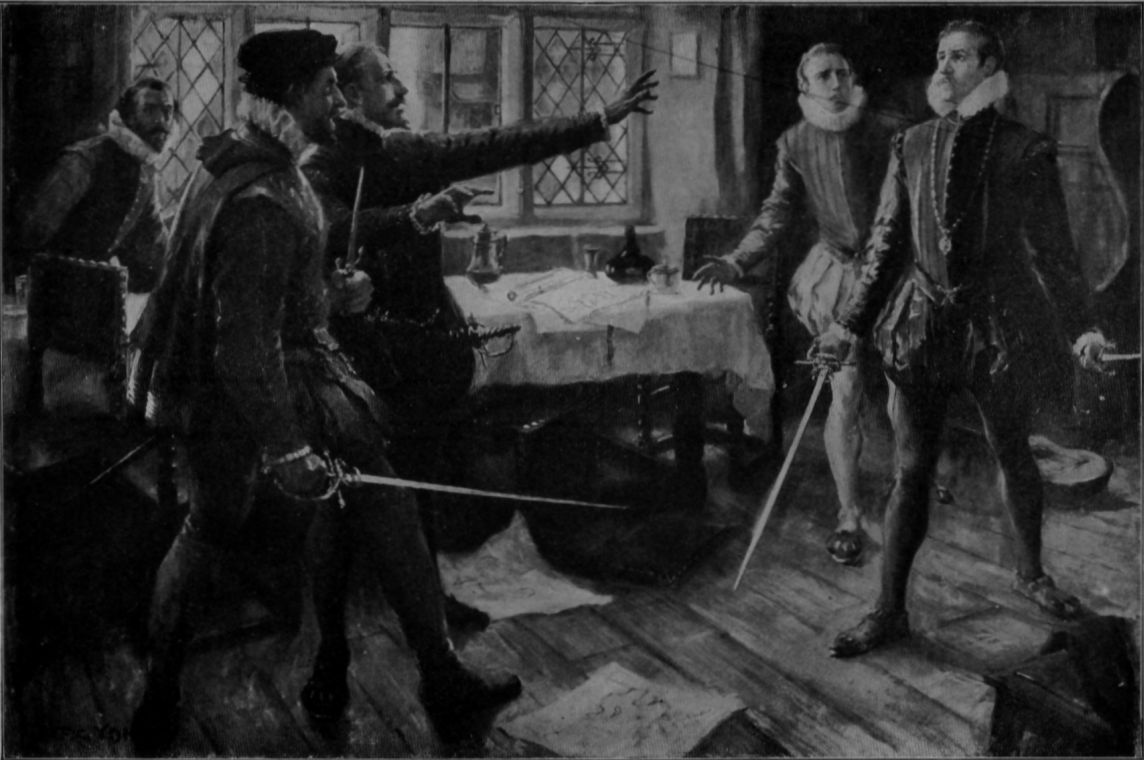

"'OH, I ENVIED HER!' SHE CRIED"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Sir Mortimer, by Mary Johnston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Sir Mortimer Author: Mary Johnston Release Date: October 20, 2004 [EBook #13812] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR MORTIMER *** Produced by Rick Niles, John Hagerson, Rick Niles, Charlie Kirschner and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

"'OH, I ENVIED HER!' SHE CRIED"

| "'OH, I ENVIED HER!' SHE CRIED" | Frontispiece |

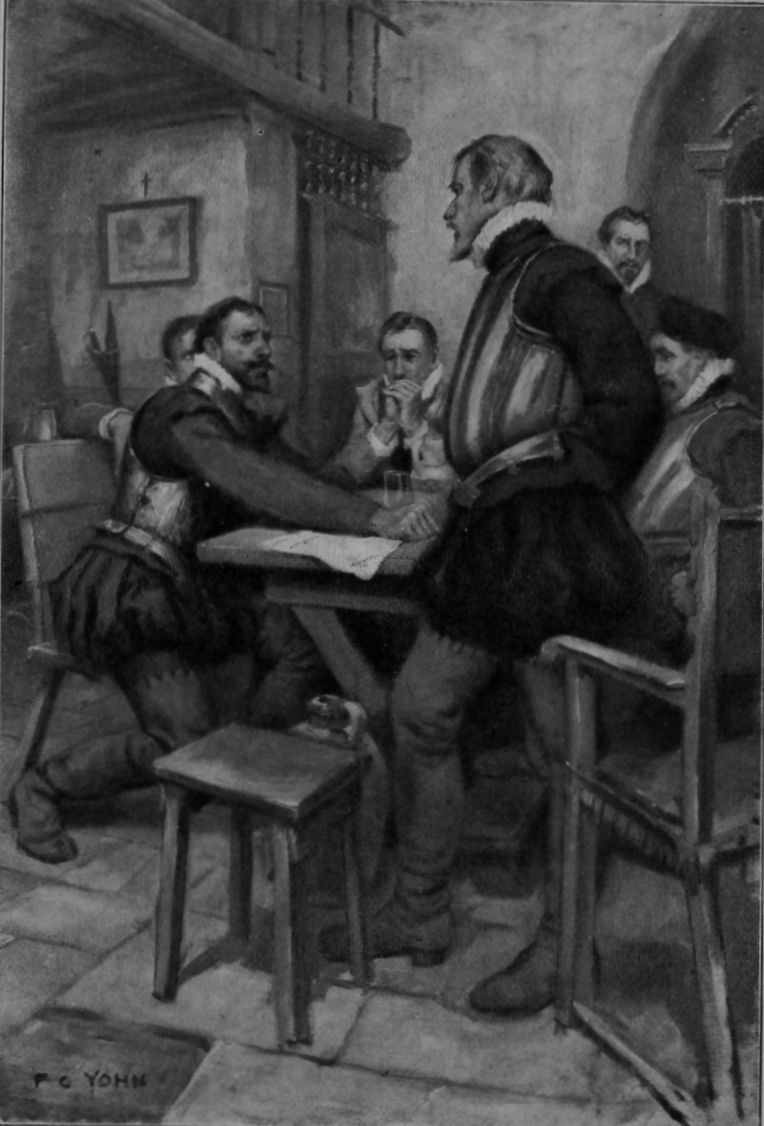

| "SIR JOHN THRUST HIMSELF BETWEEN THE TWO" | Facing p. 16 |

| "IT WAS BALDRY'S SHIP, THE LITTLE STAR" | 52 |

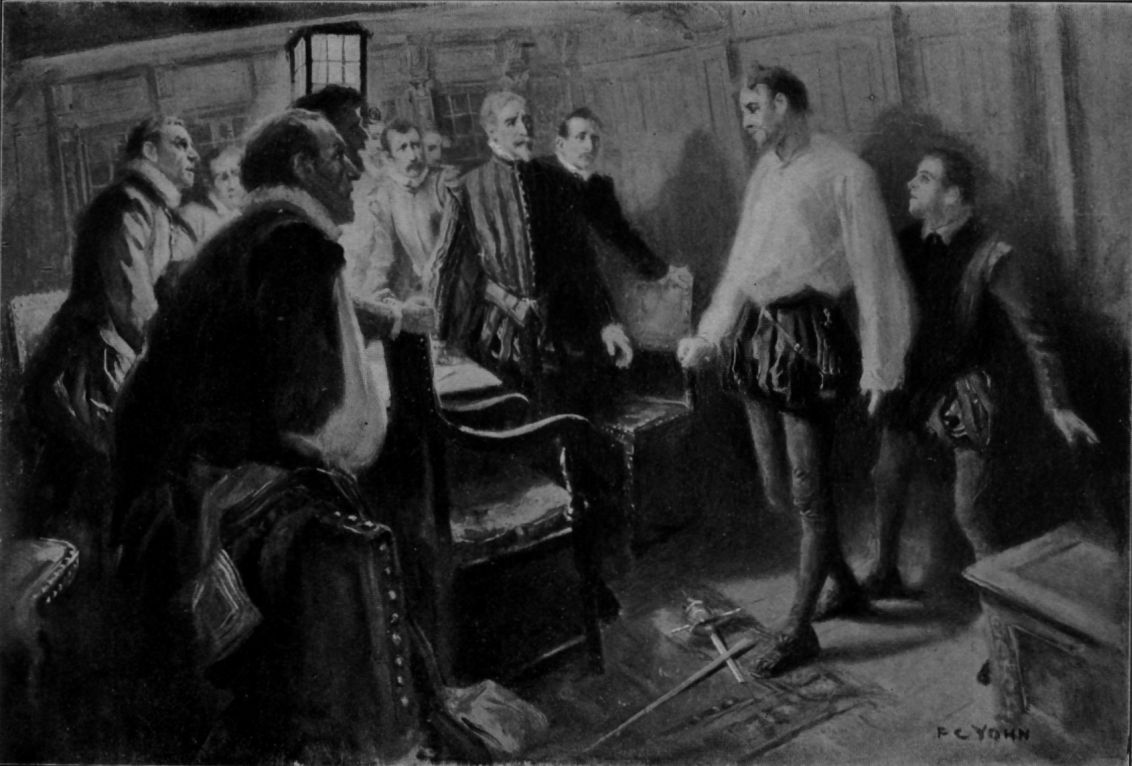

| "'DO YOU PURPOSE, THEN, THAT HE SHALL DIE?' DEMANDED BALDRY" | 138 |

| "'I BEG THE SHORTEST SHRIFT THAT YOU MAY GIVE'" | 174 |

| "'DAMARIS, THEY CALL HIM TRAITOR'" " | 190 |

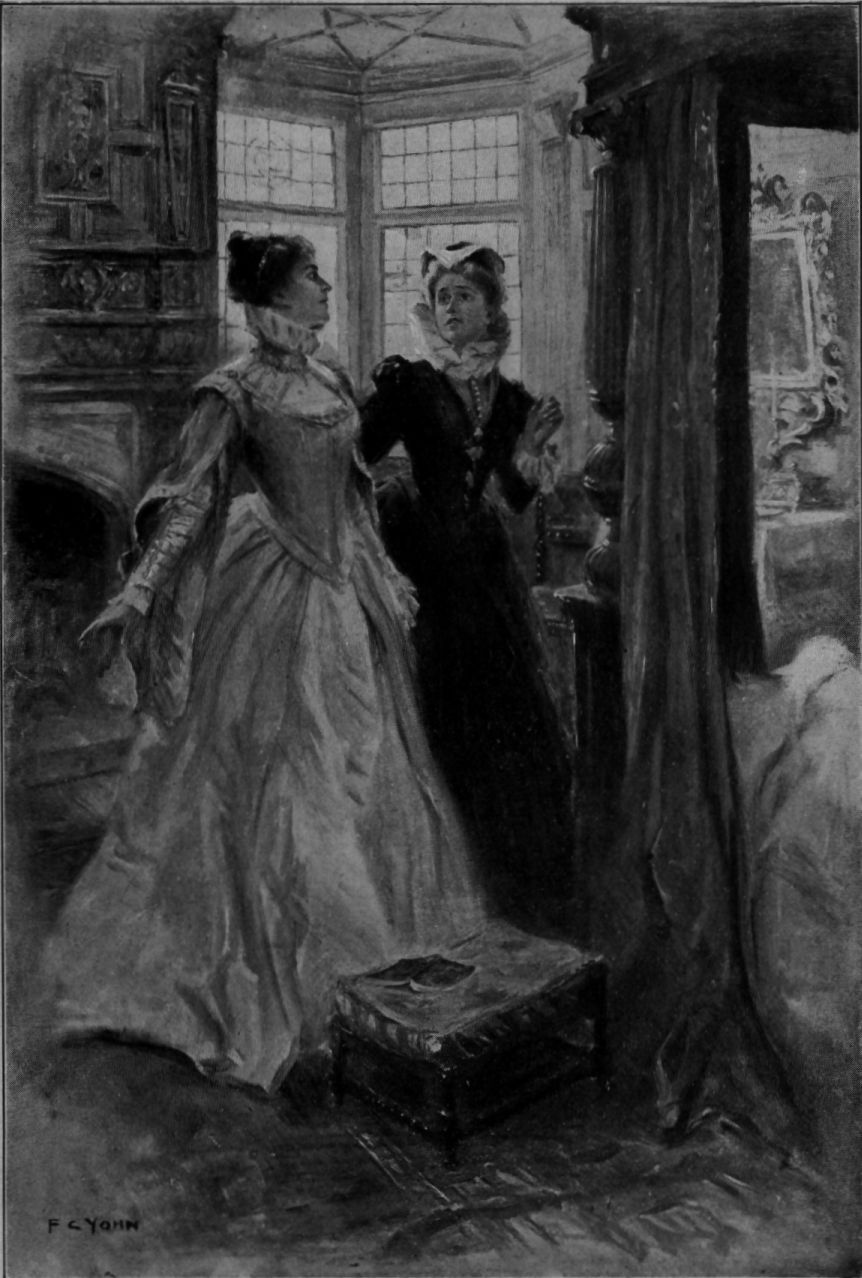

| '"AH, LOOK NOT SO UPON ME!'" " | 244 |

| "THE FRIAR PRESENTED A BLANK COUNTENANCE TO SIR MORTIMER'S QUERIES" | 260 |

| "'LAD, LAD,' HE WHISPERED, 'WHERE IS THY MASTER?'" | 284 |

ut if we return not from our adventure," ended Sir Mortimer, "if the sea claims us, and upon his sandy floor, amid his Armida gardens, the silver-singing mermaiden marvel at that wreckage which was once a tall ship and at those bones which once were animate,--if strange islands know our resting-place, sunk for evermore in huge and most unkindly forests,--if, being but pawns in a mighty game, we are lost or changed, happy, however, in that the white hand of our Queen hath touched us, giving thereby consecration to our else unworthiness,--if we find no gold, nor take one ship of Spain, nor any city treasure-stored,--if we suffer a myriad sort of sorrows and at the last we perish miserably--"

He paused, being upon his feet, a man of about thirty years, richly dressed, and out of reason good to look at. In his hand was a great wine-cup, and he held it high. "I drink to those who follow after!" he cried. "I drink to those who fail--pebbles cast into water whose ring still wideneth, reacheth God knows what unguessable shore where loss may yet be counted gain! I drink to Fortune her minions, to Francis Drake and John Hawkins and Martin Frobisher; to all adventurers and their deeds in the far-off seas! I drink to merry England and to the day when every sea shall bring her tribute!--to England, like Aphrodite, new-risen from the main! Drink with me!"

The tavern of the Triple Tun rang with acclamation, and, the windows being set wide because of the warmth of the June afternoon, the noise rushed into the street and waylaid the ears of them who went busily to and fro, and of them who lounged in the doorway, or with folded arms played Atlas to the tavern walls. "Who be the roisterers within?" demanded a passing citizen of one of these supporters. The latter made no answer; he was a ragged retainer of Melpomene, and he awaited the coming forth of Sir Mortimer Ferne, a notable encourager of all who would scale Parnassus. But his neighbor, a boy in blue and silver, squatted upon a sunny bench, vouchsafed enlightenment.

"Travellers to strange places," quoth he, taking a straw from his mouth and stretching long arms. "Tall men, swingers in Brazil-beds, parcel-gilt with the Emperor of Manoa, and playfellows to the nymphs of Don Juan Ponce de Leon his fountain,--in plain words, my master, Sir Mortimer Ferne, Captain of the Cygnet, and his guests to dinner, to wit, Sir John Nevil, Admiral of our fleet, with sundry of us captains and gentlemen adventurers to the Indies, and, for seasoning, a handful of my master's poor friends, such as courtiers and great lords and poets."

"Thinkest to don thy master's wit with his livery?" snapped the poetaster. "'Tis a chain for a man,--too heavy for thy wearing."

The boy stretched his arms again. "'Master' no more than in reason," quoth he. "I also am a gentleman. Heigho! The sun shineth hotter here than in the doldrums!"

"Well, go thy ways for a sprightly crack!" said the citizen, preparing to go his. "I know them now, for my cousin Parker hath a venture in the Mere Honour, and that is the great ship the Queen hath lent Sir John, his other ships being the Marigold, the Cygnet, and the Star, and they're all a-lying above Greenwich, ready to sail on the morrow for the Spanish Main."

"You've hit it in the clout," yawned the boy. "I'll bring you an emerald hollowed out for a reliquary--if I think on't."

Within-doors, in the Triple Tun's best room, where much sherris sack was being drunk, a gentleman with a long face, and mustachios twirled to a point, leaned his arm upon the table and addressed him whose pledge had been so general. "Armida gardens and silver-singing mermaiden and Aphrodite England quotha! Pike and cutlass and good red gold! saith the plain man. O Apollo, what a thing it is to be learned and a maker of songs!"

Athwart his laughing words came from the lower end of the board a deep and harsh voice. The speaker was Captain Robert Baldry of the Star, and he used the deliberation of one who in his drinking had gone far and fast. "I pledge all scholars turned soldiers," he said, "all courtiers who stay not at court, all poets who win tall ships at the point of a canzonetta! Did Sir Mortimer Ferne make verses--elegies and epitaphs and such toys--at Fayal in the Azores two years ago?"

There followed his speech, heard of all in the room, a moment of amazed silence. Mortimer Ferne put his tankard softly down and turned in his seat so that he might more closely observe his fellow adventurer.

"For myself, when an Armada is at my heels, the cares of the moon do not concern me," went on Baldry, with the gravity of an oracle. "Had Nero not fiddled, perhaps Rome had not burned."

"And where got you that information, sir?" asked his host, in a most courtier-like voice.

"Oh, in the streets of Rome, a thousand years ago! 'Twas common talk." The Captain of the Star tilted his cup and was grieved to find it empty.

"I have later news," said the other, as smoothly as before. "At Fayal in the Azores--"

He was interrupted by Sir John Nevil, who had risen from his chair, and beneath whose stare of surprise and anger Baldry, being far from actual drunkenness, moved uneasily.

"I will speak, Mortimer," said the Admiral, "Captain Baldry not being my guest. Sir, at Fayal in the Azores that disastrous day we did what we could--mortal men can do no more. Taken by surprise as we were, ships were lost and brave men tasted death, but there was no shame. He who held command that lamentable day was Captain--now Sir Mortimer--Ferne; for I, who was Admiral of the expedition, must lie in my cabin, ill almost unto death of a calenture. I dare aver that no wiser head ever drew safety for many from such extremity of peril, and no readier sword ever dearly avenged one day's defeat and loss. Your news, sir, was false. I drink to a gentleman of known discretion, proved courage, unstained honor--"

It needed not the glance of his eye to bring men to their feet. They rose, courtiers and university wits, soldiers home from the Low Countries, kinsmen and country friends, wealthy merchants who had staked their gold in this and other voyages, adventurers who with Frobisher and Gilbert had sailed the icy seas, or with Drake and Hawkins had gazed upon the Southern Cross, Captain Baptist Manwood, of the Marigold, Lieutenant Ambrose Wynch, Giles Arden, Anthony Paget, good men and tall, who greatly prized the man who alone kept his seat, smiling upon them from the head of the long table in the Triple Tun's best room. Baldry, muttering in his beard that he had made a throw amiss and that the wine was to blame, stumbled to his feet and stood with the rest. "Sir Mortimer Ferne!" cried they all, and drank to the seated figure. The name was loudly called, and thus it was no slight tide of sound which bore it, that high noon in the year 158-, into the busy London street. Bow Bells were ringing, and to the boy in blue and silver upon the bench without the door they seemed to take the words and sound them again and again, deeply, clearly, above the voices of the city.

Mortimer Ferne, his hand resting upon the table before him, waited until there was quiet in the tavern of the Triple Tun, then, because he felt deeply, spoke lightly.

"My lords and gentlemen," he said, "and you, John Nevil, whom I reverence as my commander and love as my friend, I give you thanks. Did we lose at Fayal? Then, this voyage, at some other golden island, we shall win! Honor stayed with us that bloody day, and shall we not now bring her home enthroned? Ay, and for her handmaidens fame and noble service and wealth,--wealth with which to send forth other ships, hounds of the sea which yet may pull down this Spanish stag of ten! By my faith, I sorrow for you whom we leave behind!"

"Look that I overtake you not, Mortimer!" cried Sidney. "Walter Raleigh and I have plans for next year. You and I may yet meet beneath a palm-tree!"

"And I also, Sir Mortimer," exclaimed Captain Philip Amadas. "Sir Walter hath promised me a ship--"

"When the old knight my father dies, and I come into my property," put in, loudly, a fancy-fired youth from Devon, "I'll go out over bar in a ship of my own! I'll have all my mariners dressed like Sir Hugh Willoughby's men in the picture, and when I come home--"

"Towing the King of Spain his plate-fleet behind you," quoth the mustachioed gentleman.

"--all my sails shall be cloth of gold," continued wine--flushed one-and-twenty. "The main-deck shall be piled with bars of silver, and in the hold shall be pearls and pieces of gold, doubloons, emeralds as great as filberts--"

"At Panama saw I an emerald greater than a pigeon's egg!" cried one who had sailed in the Golden Hind.

Sir Mortimer laughed. "Why, our very speech grows rich--as did thine long since, Philip Sidney! And now, Giles Arden, show these stay-at-home gentlemen the stones the Bonaventure brought in the other day from that coast we touched at two years agone. If we miss the plate-fleet, my masters, if we find Cartagena or Santa Marta too strong for us, there is yet the unconquered land, the Hesperidian garden whence came these golden apples! Deliver, good dragon!"

He of the mustachios laid side by side upon the board three pieces of glittering rock, whereat every man bent forward.

"Marcasite?" said one, doubtfully.

"El madre del oro?" suggested another.

"White spar," said Arden, authoritatively, "and containeth of gold ten pounds to the hundredweight. Moreover--" He sifted down upon the dark wood beside the stones a thimbleful of dull yellow grains. "The sands of Pactolus, gentlemen! Sure 'twas in no Grecian river that King Midas bathed himself!"

Those of the company to whom had never before been exhibited these samples of imperial riches craned their necks, and the looks of some were musing and of others keenly eager. The room fell silent, and still they gazed and gazed at the small heap of glistening stones and those few grains of gold. They were busy men in the vanguard of a quickened age, and theirs were its ardors, its Argus-eyed fancy and potent imagination. Show them an acorn, and straightway they saw a forest of oaks; an inch of a rainbow, and the mind grasped the whole vast arch, zenith-reaching, seven-colored, enclosing far horizons. So now, in addition to the gleaming fragments upon the table before them, they saw mountain ranges with ledges of rock all sparkling like this ore, deep mines with Indian workers, pack-trains, and burdened holds of ships.

After a time one lifted a piece of the ore, hesitatingly, as though he made to take up all the Indies, scrutinized it closely, weighed it, passed it to his neighbor. It went the round of the company, each man handling it, each with the talisman between his fingers gazing through the bars of this present hour at a pageant and phantasmagoria of his own creating. At last it came to the hand of an old merchant, who held it a moment or two, looking steadfastly upon it, then slowly put it down.

"Well," said he, "may God send you furthering winds, Sir Mortimer and Sir John, and make their galleons and galliasses, their caravels and carracks, as bowed corn before you! Those of your company who are to die, may they die cleanly, and those who are to live, live nobly, and may not one of you fall into the hands of the Holy Office."

"Amen to that, Master Hudson," quoth Arden.

"The Holy Office!" cried a Banbury man. "I had a cousin, sirs,--an honest fellow, with whom I had gone bird's-nesting when we were boys together! He was master of a merchantman--the Red Lion--that by foul treachery was taken by the Spaniards at Cales. The priests put forth their hands and clutched him, who was ever outspoken, ever held fast to his own opinion!... To die! that is easy; but when I learned what was done to him before he was let to die--" The speaker broke off with an oath and sat with fixed gaze, his hand beating upon the table a noiseless tattoo.

"To die," said Mortimer Ferne slowly. "To die cleanly, having lived nobly--it is a good wish, Master Hudson! To die greatly--as did your cousin, sir,--a good knight and true, defending faith and loyalty, what more consummate flower for crown of life? What loftier victory, supremer triumph? Pain of body, what is it? Let the body cry out, so that it betray not the mind, cheat not the soul into a remediless prison of perdition and shame!"

He drank of his wine, then with a slight laugh and wave of his hand dismissed a subject too grave for the hour. A little later he arose with his guests from the table, and since time was passing and for some there was much to do, men began to exchange farewells. To-morrow would see the adventurers gone from England; to-day kinsmen and friends must say good-by, warmly, with clasping of hands and embracing, even with tears, for it was an age when men did not scorn to show emotion. A thousand perils awaited those who went, nor for those who stayed would time or tide make tarrying. It was most possible that they who parted now would find, this side eternity, no second inn of meeting.

From his perch beside the door, the boy in blue and silver watched his master's guests step into the sunlight and go away. A throng had gathered in front of the tavern, for the most part of those within were men of note, and Sir John Nevil's adventure to the Indies had long been general talk. Singly or in little groups the revellers issued from the tavern, and for this or that known figure and favorite the crowd had its comment and cheering. At last all were gone save the adventurers themselves, who, having certain final arrangements to make, stayed to hold council in the Triple Tun's long room.

Their conference was not long. Presently came forth Captain Baptist Manwood of the Marigold with his lieutenants, Wynch and Paget, and Captain Robert Baldry of the Star. The four, talking together, started towards the waterside where they were to take boat for the ships that lay above Greenwich, but ere they had gone forty paces Baldry felt his sleeve twitched. Turning, he found at his elbow the blue and silver sprig who served Sir Mortimer Ferne.

"Save you, sir," said the boy. "There's a gentleman at the Triple Tun desires your honor would give him five minutes of your company."

"I did expect a man of my acquaintance, a Paul's man with a good rapier to sell," quoth Baldry. "Boy, is the gentleman a lean gentleman with a Duke Humphrey look? Wait for me, sirs, at the stairs!"

Within the Triple Tun, Sir John Nevil yet sat at table pondering certain maps and charts spread out before him, while Mortimer Ferne, having re-entered the room after a moment's absence, leaned over his commander's shoulder and watched the latter's forefinger tracing the coastline from the Cape of Three Points to Golden Castile. By the window stood Arden, while on a settle near him lounged Henry Sedley, lieutenant to the Captain of the Cygnet; moreover a young gentleman of great promise, a smooth, dark, melancholy beauty, and a pretty taste in dress. In his hands was a gittern which had been hanging on the wall above him, and he played upon it, softly, a sweet and plaintive air.

In upon these four burst Baldry, who, not finding the Paul's man and trader in rapiers, drew himself up sharply. Sir Mortimer came forward and made him a low bow, which he, not to be outdone in courtesy, any more than in weightier matters, returned in his own manner, fierce and arrogant as that of a Spanish conquistador.

"Captain Robert Baldry, I trusted that you would return," said Ferne. "And now, since you are no longer guest of mine, we will resume our talk of Fayal in the Azores. Your gossips lied, sir; and he who, not staying to examine a quarrel, becomes a repeater of lies, may chance upon a summer day, in a tavern such as this, to be called a liar. My cartel, sir!"

He flung his glove, which scarce had felt the floor before the other snatched it up. "God's death! you shall be accommodated!" he cried. "Here and now, is't not? and with sword and dagger? Sir, I will spit you like a lark, or like the Spaniard I did vanquish for a Harry shilling at El Gran' Canario, last Luke's day--"

The three witnesses of the challenge sprang to their feet, the gittern falling from Sedley's hands, and Sir John's papers fluttering to the floor. The latter thrust himself between the two who had bared their weapons. "What is this, gentlemen? Mortimer Ferne, put up your sword! Captain Baldry, your valor may keep for the Spaniards! Obey me, sirs!"

"Let be, John Nevil," said Ferne. "To-morrow I" become your sworn man. To-day my honor is my Admiral!"

"Will you walk, Sir Mortimer Ferne?" demanded Baldry. "The Bull and Bear, just down the street, hath a little parlor--a most sweet retired place, and beareth no likeness to the poop of the Mere Honour. Sir John Nevil, your servant, sir--to-morrow!"

"SIR JOHN THRUST HIMSELF BETWEEN THE TWO"

"My servant to-day, sir," thundered the Admiral, "in that I will force you to leave this quarrel! Death of my life! shall this get abroad? Not that common soldiers or mariners ashore fall out and cudgel each other until the one cannot handle a rope nor the other a morris-pike! not that wild gallants, reckless and broken adventurers whose loss the next daredevil scamp may supply, choose the eve of sailing for a duello, in which one or both may be slain; but that strive together my captains, men vowed to noble service, loyal aid, whose names are in all mouths, who go forth upon this adventure not (I trust in God) with an eye single to the gain of the purse, but thinking, rather, to pluck green laurels for themselves, and to bring to the Queen and England gifts of waning danger, waxing power! What reproach--what evil augury--nay, perhaps, what maiming of our enterprise! Leaders and commanders that you are, with your goodly ships, your mariners and soldiers awaiting you, and above us all the lode-star of noblest duty, truest honor--will you thus prefer to the common good your private quarrel? Nay, now, I might say 'you shall not'; but, instead, I choose to think you will not!"

The speech was of the longest for the Admiral, who was a man of golden silences. His look had been upon Baldry, but his words were for Mortimer Ferne, at whom he looked not at all. "I have been challenged, sir," cried Baldry, roughly. "Draw back? God's wounds, not I!"

His antagonist bit his lip until the blood sprang. "The insult was gross," he said, with haughtiness, "but since I may not deny the truth of your words, John Nevil, I will reword my cartel. Captain Robert Baldry, I do solemnly challenge you to meet me with sword and dagger upon that day which sees our return to England!"

"A far day that, perhaps!" cried Baldry. "But so be it! I'll not fail you, Sir Mortimer Ferne. Look that you fail not me!"

"Sir!" cried Ferne, sharply.

The Admiral struck the table a great blow. "Gentlemen, no more of this! What! will you in this mood go forth side by side to meet a common foe? Nay, I must have you touch hands!"

The Captain of the Cygnet held out his hand. He of the Star first swore, then burst into a great laugh; finally laid his own upon it.

"Now we are turtle-doves, Sir John, nothing less! and the Star and the Cygnet may bill and coo from the Thames to Terra Firma!" Suddenly he ceased to laugh, and let fall his hand. "But I have not forgotten," he said, "that at Fayal in the Azores I had a brother slain."

He was gone, swinging from the room with scant ceremony, loudly ordering from his path the loiterers at the inn door. They whose company he had quitted were silent for a moment; then said Sir Mortimer, slowly: "I remember now--there was a Thomas Baldry, master of the Speedwell. Well, it was a sorry business that day! If from that muck of blood and horror was born Detraction--"

"The man was mad!" thrust in young Sedley, hotly. "Detraction and you have no acquaintance."

Ferne, with a slight laugh, stooped to pick up the fallen gittern. "She kept knighthood and me apart for a year, Henry. 'Tis a powerful dame, a most subtle and womanish foe, who knoweth not or esteemeth not the rules of chivalry. Having yielded to plain Truth, she yet, as to-day, raiseth unawares an arm to strike." He hung the gittern upon its peg, then went across to the Admiral and put both hands upon his shoulders. The smile was yet upon his lips, but his voice had a bitter ring. "John, John," he said, "old wounds leave not their aching. That tall, fanfaronading fellow hath a power to anger me,--not his words alone, but the man himself.... Well, let him go until the day we come sailing back to England! For his words--" He paused and a shadow came over his face. "Who knows himself?" he said. "There are times when I look within and doubt my every quality that men are pleased to give me. God smiles upon me--perhaps He smiles with contempt!... I would that I had followed, not led, that day at Fayal!"

Arden burst into a laugh. The Admiral turned and stared at him who had spoken with a countenance half severity, half deep affection. "What! stings that yet?" he said. "I think you may have that knowledge of yourself that you were born to lead, and that knowledge of higher things that shame is of the devil, but defeat ofttimes of God. How idly do we talk to-day!"

"Idly enough," agreed Ferne with a quick sigh. He lifted his hands from the other's shoulders, and with an effort too instantaneous to be apparent shook off his melancholy. Arden took up his hat and swung his short cloak over his shoulder.

"Since we may not fight," he said, "I'll e'en go play. There's a pretty lady hard by who loves me dearly. I'll go tell her tales of the Carib beauties. Master Sedley, you are for the court, I know. Would the gods had sent me such a sister! Do you go to Leicester House, Mortimer? If not, my fair Discretion hath a mate--"

"I," answered Ferne, "am also for Greenwich."

Arden laughed again. "Her Grace gives you yet another audience? Or is it that hath come to court that Nonpareil, that radiant Incognita, that be-rhymed Dione at whose real name you keep us guessing? I thought the violet satin was not for naught!"

"In that you speak with truth," said the other, coolly, "for thirty acres of good Devon land went to its procuring. Since you are for the court, Henry Sedley, one wherry may carry the two of us."

When the two adventurers and the boy in blue and silver had made half the distance to the pleasant palace where, like a flight of multicolored birds, had settled for the moment Elizabeth's migratory court, the gentlemen became taciturn and fell at length to silent musing, each upon his own affairs. The boy liked it not, for their discourse had been of armor and devices, of war-horses and Spanish swords, and such knightly matters as pleased him to the marrow. He himself (Robin-a-dale they called him) meant to be altogether such a one as his master in violet satin. Not a sea-dog simply and terrible fighter like Captain Manwood or Ambrose Wynch, nor a ruffler like Baldry, nor even a high, cold gentleman like Sir John, who slew Spaniards for the good of God and the Queen, and whose slow words when he was displeased cut like a rope's end. But he would fight and he would sing; he would laugh with his foe and then courteously kill him; he would know how to enter the presence, how to make a great Queen smile and sigh; and then again, amid the thunder and reek of the fight, on decks slippery with blood, he would strain, half naked, with the mariners, he would lead the boarders, he would deal death with a flashing sword and a face that seen through the smoke wreaths was so calm and high!--And the Queen might knight him--one day the Queen might knight him. And the people at home, turning in the street, would look and cry, "'Tis Sir Robert Dale!" as now they cry "Sir Mortimer Ferne!"

Robin-a-dale drew in his breath and clenched his hands with determination; then, the key being too high for long sustaining, came down to earth and the contemplation of the bright-running Thames, its shifting banks, and the shipping on its bosom. The river glided between tall houses, and there were voices on the water, sounding from stately barges, swift-plying wherries, ships at anchor, both great and small. Over all played mild sunshine, hung pale blue skies. The boy thought of other rivers he had seen and would see again, silent streams gliding through forests of a fearful loveliness, miles of churned foam rushing between black teeth of jagged rock to the sheer, desperate, earth-shaking cataract, liquid highways to the realms of strange dreams! He turned involuntarily and met his master's eye. Between these two, master and boy, knave and knight, there was at times so strange a comprehension that Robin-a-dale was scarcely startled to find that his thoughts had been read.

"Ay, Robin," said Ferne, smiling, "other and stranger waters than those of Father Thames! And yet I know not. Life is one, though to-day we glide through the sunshine to a fair Queen's palace, and to-morrow we strive like fiends from hell for those two sirens, Lust of Gold and Lust of Blood. Therefore, Robin, an you toss your silver brooch into the Thames it may come to hand on the other side of the world, swirling towards you in some Arethusa fountain."

"I see the ships, master!" cried the boy. "Ho, the Cygnet, the bonny white Cygnet!"

They lay in a half-moon, with the westering sun striking full upon the windows of their high, castellated poops. Their great guns gleamed; mast and spar and rigging made network against the blue; high in air floated bright pennants and the red cross in the white field. To and fro plied small boats, while over the water to them in the wherry came a pleasant hum of preparation for the morrow's sailing. Upon the Cygnet, lying next to the Mere Honour, and a very noble ship, the mariners began to sing.

"Shall we not row more closely?" cried Sedley. "The Cygnet knows not that it is you who pass!"

Sir Mortimer laughed. "No, no; I come to her arms from the Palace to-night! Trouble her not now with genuflections and salutings." His eyes dwelt with love upon his ship. "How clearly sounds the singing!" he said.

So clearly did it sound over the water that it kept with them when the ships were passed. Robin-a-dale had his fancies, to which at times he gave voice, scarce knowing that he had spoken. "'Tis the ship herself that sings," he now began to say to himself in a low voice, over and over again. "'Tis the ship singing, the ship singing because she goes on a voyage--a long voyage!"

"Sirrah!" cried his master, somewhat sharply. "Know you not that the swan sings but upon one voyage, and that her last? 'Tis not the Cygnet that sings, but upon her sing my mariners and soldiers, for that they go forth to victory!"

He put his hands behind his head, and with a light in his eyes looked back to the dwindling ships. "Victory!" he repeated beneath his breath. "Such fame, such service, as that earthworm, that same Detraction, shall raise no more her lying head!" He turned to Sedley: "I am glad, Harry, that your lot is cast with mine. For we go forth to victory, lad!"

The younger man answered him impetuously, a flush of pride mounting to his smooth, dark cheek. "I doubt it not, Sir Mortimer, nor of my gathering laurels, since I go with you! I count myself most fortunate." He threw back his head and laughed. "I have no lady-love," he said, "and so I will heap the laurels in the lap of my sister Damaris."

By now, the tide being with them, they were nearing Greenwich House. Ferne dipped his hand into the water, then, straightening himself, shook from it the sparkling drops, and looked in the face of the youth who was to make with him his maiden voyage.

"You could heap laurels in the lap of no sweeter lady," he said, courteously. "I thought you went on yesterday to say farewell to Mistress Damaris Sedley."

"Why, so I did," said the other, simply. "We said farewell with our eyes in the presence, while the Queen talked with my Lord of Leicester; in the antechamber with our hands; in the long gallery with our lips; and when we reached the gardens, and there was none at all to see, we e'en put our arms about each other and wept. It is a right noble wench, my sister, and loves me dearly. And then, while we talked, one of her fellow maids came hurriedly to call her, for her Grace would go a-hawking, and Damaris was in attendance. So I swore I would see her again to-day though 'twere but for a moment."

The rowers brought the wherry to the Palace landing. Sir Mortimer, stepping out upon the broad stairs, began to mount them somewhat slowly, Sedley and Robin-a-dale following him. Half-way up, Sedley, noting the rich suit worn so point-device, and aware of how full in the sunshine of the Queen's favor stood for the moment his Captain, asked if he were for the presence. Ferne shook his head: "Not now.... May I know, Henry, where you and your sister meet?"

"In the little covert of the park where we said good-by on yesterday." There were surprise and some question in the youth's upward glance at the man in violet satin, standing a step or two above him, his hand resting upon the stone balustrade, a smile in his eyes, but none upon the finely cut lips, quite grave and steady beneath the slight mustache.

Ferne, reading the question, gave, after just a moment's pause, the answer. "My dear lad," he said, and the smile in his eyes grew more distinct and kindly, "to Mistress Damaris Sedley I also would say farewell." He laid his hand upon the young man's shoulder. "For I would know, Henry--I would know if through all the days and nights that await us over the brim of to-morrow I may dream of an hour to come when that dear and fair lady shall bid me welcome." His eyes looked into the distance, and the smile had crept to his lips. "It was my meaning to speak to her to-night before I left the Palace, but this chance offers better. Will you give me precedence, Henry? let me see and speak to your sister alone in that same covert of which you tell me?"

"But--but--" stammered Sedley.

Sir Mortimer laughed. "'But ... Dione!' you would say. 'Ah, faithless poet, forsworn knight!' you would say. Not so, my friend." He looked far away with shining eyes. "That unknown nymph, that lady whom I praise in verse, whose poet I am, that Dione at whose real name you all do vainly guess--it is thy sister, lad! Nay,--she knows me not for her worshipper, nor do I know that I can win her love. I would try ..."

Sedley's smooth cheek glowed and his eyes shone. He was young; he loved his sister, orphaned like himself and the neglected ward of a decaying house; while to his ardent fancy the man above him, superb in his violet dress, courteous and excellent in all that he did, was a very Palmerin or Amadis de Gaul. Now, impetuously, he put his hand upon that other hand touching his shoulder, and drew it to his lips in a caress, of which, being Elizabethans, neither was at all ashamed. In the dark, deeply fringed eyes that he raised to his leader's face there was a boyish and poetic adoration for the sea-captain, the man of war who was yet a courtier and a scholar, the violet knight who was to lead him up the heights which long ago the knight himself had scaled.

"Damaris is a fair maid, and good and learned," he said in a whisper, half shy, half eager. "May you dream as you wish, Sir Mortimer! For the way to the covert--'tis by yonder path that's all in sunshine."

eneath a great oak-tree, where light and shadow made a checkered round, Mistress Damaris Sedley sat upon the earth in a gown of rose-colored silk. Across her knee, under her clasped hands, lay a light racket, for she had strayed this way from battledore and shuttlecock and the sprightly company of maids of honor and gentlemen pensioners engaged thereat. She was a fair lady, of a clear pallor, with a red mouth very subtly charming, and dark eyes beneath level brows. Her eyes had depths on depths: to one player of battledore and shuttlecock they were merely large brown orbs; another might find in them worlds below worlds; a third, going deeper, might, Actæon-like, surprise the bare soul. A curiously wrought net of gold caught her dark hair in its meshes, and pearls were in her ears, and around the white column of her throat rising between the ruff's gossamer walls. She fingered the racket, idly listening the while for a foot-fall beyond her round of trees. Hearing it at last, and taking it for her brother's, she looked up with a proud and tender smile.

"Fie upon thee for a laggard, Henry!" she began: "I warrant thy Captain meets not his Dione with so slow a step!" Then, seeing who stood before her, she left her seat between the oak roots and curtsied low. "Sir Mortimer Ferne," she said, and rising to her full height, met his eyes with that deeper gaze of hers.

Ferne advanced, and bending his knee to the short turf, took and kissed her hand. "Fair and sweet lady," he said, "I made suit to your brother, and he has given me, his friend, this happy chance. Now I make my supplication to you, to whom I would be that, and more. All this week have I vainly sought for speech with you alone. But now these blessed trees hem us round; there is none to spy or listen--and here is a mossy bank, fit throne for a faery queen. Will you hear me speak?"

The maid of honor looked at him with rose bloom upon her cheeks, and in her eyes, although they smiled, a moisture as of half-sprung tears. "Is it of Henry?" she asked. "Ah, sir, you have been so good to him! He is very dear to me.... I would that I could thank you--"

As she spoke she moved with him to the green bank, sat down, and clasped her hands about her knees. The man who on the morrow should leave behind him court and court ways, and all fair sights such as this, leaned against the oak and looked down upon her. When, after a little silence, he began to speak, it was like a right courtier of the day.

"Fair Mistress Damaris," he said, "your brother is my friend, but to-day I would speak of my friend's friend, and that is myself, and your servant, lady. To-morrow I go from this garden of the world, this no-other Paradise, this court where Dian reigns, but where Venus comes as a guest, her boy in her hand. Where I go I know not, nor what thread Clotho is spinning. Strange dangers are to be found in strange places, and Jove and lightning are not comfortable neighbors. Ulysses took moly in his hand when there came to meet him Circe's gentlemen pensioners, and Gyges's ring not only saved him from peril, but brought him wealth and great honor. What silly mariner in my ship hath not bought or begged mithridate or a pinch of achimenius wherewith to make good his voyage? And shall not I, who have much more at stake, procure me an enchantment?"

The lady's fringed lids lifted in one swift upward glance. "Your valor, sir, should prove your surest charm. But there is the new alchemist--"

"He cannot serve my need, hath not what I want. I want--" He hesitated for a moment; then spoke on with a certain restrained impetuosity that became him well: "There is a honey-wax which, being glazed about the heart, holdeth within it, forever, a song so sweet that the chanting of the sirens matters not; there is that precious stone which, as the magnet draweth the iron, so ever constraineth Honor, bidding him mount every breach, climb higher, higher, higher yet! there is that fragrant leaf which oft is fed with tears, and often sighing worn, yet, so worn, inspireth valor more heroical than that of Achilles! Such a charm I seek, sweet lady."

Mistress Damaris Sedley, a favorite of the Countess of Pembroke, and a court lady of some months' standing, could parley euphuism with the best, and yet to-day it seemed to her that plain English might better serve the turn. However:

"Good gentleman," she answered, sedately, "I think that few are the bees that gather so dainty a wax, but if they be flown to Hymettus, then to Hymettus might one follow them; also that precious stone may be found, though, alack! often enough a man is so poor a lapidary that, seeing only the covering of circumstances, he misses the true sapphire! and for that fragrant leaf, I have heard of it in my day--"

"It is called truelove," he said.

Damaris kept to the card: "My marvel, sir, is to hear you speak as though you had not the charm you seem to seek. One blossom of the tree Alpina is worth all store of roses; one ruby outvalueth many pearls; he who hath already the word of magic needeth to buy no Venus's image; and Sir Mortimer Ferne, secure in Dione's love, saileth, methinks, in crystal seas, with slight danger from storm and wreck."

"Secure in Dione's love!" repeated Ferne. "Ah, lady, your shaft has gone wide. I have sailed, and sailed, and sailed--ay, and in crystal seas--and have seen blooms fairer than the tree Alpina, and have been in the land of emeralds and where pearls do grow, and yet have never gathered the fragrant leaf, that leaf of true and mutual love. It should grow with the laurel and blend with the bay--ay, and be not missing from the cypress wreath! But as yet I have it not--as yet I have it not."

Damaris gazed upon him with brown, incredulous eyes, and when she spoke her words came somewhat breathlessly, having quite outgone the courtly affectation of similes run mad.

"What mean you, sir? Not the love of Astrophel for Stella is better known than that of Cleon for Dione! And, lo! now your own lines--Master Dyer showed them to me but the other day copied into his book of songs:

'Nor in my watery wanderings am I crossed;

Where haven's wanted, there I haven find,

Nor e'er for me is star of guidance lost--'"

Her voice breaking a little, Ferne made nearer approach to the green bank where she rested. "Do you learn by heart my verses, lady?" he asked.

"Ay," she answered, "I did ever love sweet poetry." Her voice thrilled, and she gazed past him at the blue heaven showing between the oak leaves. "If prayer with every breath availeth," she said, "no doubt your Dione will bring your safe return."

"Of whom do I write, calling her Dione?"

She shook her head. "I know not. None of us at court knows. Master Dyer saith--but surely that one is not worthy--" She ceased to speak, nor knew there had been in her tone both pain and wistfulness. Presently she laughed out, with the facile gayety that one in her position must needs be practised in. "Ah, sir, tell me her name! Is she of the court?"

He nodded, "Yes."

Damaris clapped her hands. "What lovely hypocrite have we among us? What Lady Pure Innocence, wondering with the rest of the world?--and all the while Cleon's latest sonnet hot against her heart! Is she tall, sir, or short?"

"Of your height."

The lady shrugged. "Oh, I like not your half-way people! And her hair--but halt! We know her hair is dark:

'Ah, darkness loved beyond all light!'

Her eyes--"

He bent his head, moving yet nearer to her. "Her eyes--her eyes are wonderful! Where got you your eyes, Dione--Dione?"

Crimsoning deeply, Damaris started up, the racket escaping her clasp, and her hands going out in a gesture of dismay and anger. "Sir,--sir," she stammered, "since you make a mock of me, I will begone. No, sir; let me pass! Ah, ... how unworthy of you!"

Ferne had caught her by the wrists. "No, no! Dear lady, to whom I am wellnigh a stranger--sweetheart with whom I have talked scarce thrice in all my life--my Dione, to whom my heart is as a crystal, to whom I have written all things! I must speak now, now before I go this voyage! Think you it is in me to vex with saucy words, to make a mock of any gentle lady?"

"I know not what to think," she answered, in a strange voice. "I am too dull to understand."

"Think that I tell you God's truth!" he cried. "Understand that--" He checked himself, seeing how pale she was and how flutteringly came her breath; then, trained as she herself to instantly draw an airy veil between true feeling and the exigency of the moment, he became once more the simple courtier. "You read the songs that I make, sweet lady," he said, "and now will you listen while I tell you a story, a novelle? So I may make you to understand."

As he spoke he motioned to the mossy bank which she had quitted. She raised her troubled eyes to his; then, with her scarlet lip between her teeth, she took her seat again. For a minute there was silence in the little grove, broken only by the distant voices of the players whose company she had forsworn; then Ferne began his story:

"In a fair grassy plain, not many leagues removed from the hill Parnassus, a shepherd named Cleon sat upon a stone, piping to himself while he watched his sheep, and now and then singing aloud, so that the other shepherds and dwellers of the plain, and travellers through it, paused to hear his song. He sang not often, and often he laid his pipe aside, for he had much to think of, having been upon the other side of the mountain, and having seen cities and camps and courts,--for indeed he was not always shepherd. And now, because his thoughts left the plain to hover over the place where danger is, to visit strange coasts and Ultima Thule, to strain ever towards those islands of the blest where goes the man who has endured to the end, his notes when he sang or when he played became warlike, resolved, speaking of death and fame and stern things, or of things of public weal.... But all the time the shepherd was a lonely man, because his spirit was too busy to find ease for itself, and because, though he had helped other shepherds in the building of their cottages, his own heart had no hearthstone where he might warm himself and be content. Sometimes as he lay alone upon the bare earth, counting the stars, he caught the gleam from such a home clear shining over the plain, and he told himself that when he had numbered all the stars like sheep in a fold, then would he turn and give his heart rest beside some lower light.... So he kept on with his Phrygian melodies, and they brought him friends and enemies; but no lover hastening over the plain stayed to listen, and the shepherd was sorry for that, because he thought that the others, though they heard, did not fully understand."

The narrator paused. The maid of honor's hands were idle in her lap; with level gaze she sat in a dream. "Yet some there be who might have understood," she said, and scarce knew that she had spoken.

"Now Cleon had a friend whom he loved, the shepherd Astrophel, who sang more sweetly than any in all that plain, and Astrophel would oft urge Cleon to his dwelling, which was a fair one, with shady groves, sunny lawns, and springing fountains."

"Ah, sweet Sidney, dear Penshurst!" breathed the lady, softly.

"Now upon a day--indeed, 'tis little more than a year ago--Cleon, returning to the plain from a far journey, found Astrophel, who, taking no denial, would have him to those sunny lawns and springing fountains. There was dust upon the spirit of the shepherd Cleon: that had happened which had left in his mouth the taste of Dead Sea fruit; almost was he ready to break his pipe across, and to sit still forever, covering his face. But Astrophel, knowing in himself how he would have felt in his dearest part that wound which his friend had received, was skilled to heal, and with wise counsel and honeyed words at last won Cleon to visit him."

"A year and more ago," said Damaris, dreamily.

"On such a day as this, Cleon and Astrophel came to the latter's home, where, since Astrophel was as a magnet-stone to draw unto him the noblest of his kind, they found a goodly gathering of the chiefest of the dwellers in the plain. Nor were lacking young shepherdesses, nymphs, and ladies as virtuous as they were fair, for Astrophel's sister was such an one as Astrophel's sister should be."

"Most dear, most sweet Countess," murmured Damaris.

"Cleon and Astrophel were made welcome by this goodly company, after which all addressed themselves to those sports of that country for which the day had been devised. But though he made merry with the rest, nor was in anything behind them, Cleon's heart was yet heavy within him.... Aurora, fast flying, turned a rosy cheek, then the night hid her path with his spangled mantle, and all this company of shepherdish folk left the gray lawns for Astrophel's house, that was lit with clear wax and smelled sweet of roses. And after a while, when there had been comfit talk and sipping of sweet wine, one sang, and another followed, while the company listened, for they were of those who have ears to hear. Colin sang of Rosalind; Damon, of Myra; Astrophel, of Stella; Cleon, of--none of these things. 'Sing of love!' they cried, and he sang of friendship;' Of the love of a woman!' and he sang to the honor of a man."

"But in that contest he won the Countess's pearl," said the maid of honor, her chin in her hands; "I knew (dear lady!) what, being woman, was her inmost thought, and in my heart I did applaud her choice."

The man bent his eyes upon her for a moment, then went on with his story, but somewhat slowly.

"When it had thus ended the day, that goodly company betook itself to rest. But Cleon tossed upon his bed, and at the dawn, when the birds began to sing, he arose, dressed himself, and went forth into the dewy gardens of that lovely place. Here he walked up and down, for his unrest would not leave him, and his heart hungered for food it had never tasted.... There was a fountain springing from a stone basin, and all around were set rose-bushes, seen dimly because of the mist. Presently, when the light was stronger, issued from the house one of those nymphs whom Astrophel's sister delighted to gather around her, and coming to the fountain, began to search about its rim for a jewel that had been lost. She moved like a mist wreath in that misty place, but Cleon saw that her eyes were dark, and her lips a scarlet flower, and that grace was in all her motions. He remembered her name, and that she was loved of Astrophel's sister, and how sweet a lady she was called. Now he watched her weaving paces in the mist, and his fancy worked.... The mist lifted, and a sudden sunshine lit her into splendor; face, form, spirit, all, all her being into fadeless splendor--into fadeless splendor, Dione!"

The maid of honor left once more her grassy throne, and turning from him, moved a step away, then with raised arms clasped her hands behind her head. Her upturned face was hidden from him, but he saw her white bosom rise and fall. He had made pause, but now he continued his story, though with a changed voice.

"And Cleon, going to her with due greeting, knelt: she thought (sweet soul!) to aid her in her search, but indeed he knelt to her, for now he knew that the gods had given him this also--to love a woman. But because the blind boy's shaft, designed to work inward ever deeper and deeper until it reached the heart's core, did now but ensanguine itself, he made no cry nor any sign of that sweet hurt. He found and gave the nymph the jewel she had lost, and broke for her the red, red roses, and while the birds did carol he led her through the morning to the entrance of the house. Up the stone stairs went she, and turned in splendor at the top. A red rose fell ... the sunlight passed into the house."

The voice of the speaker altered, came nearer the ear of her who stood with heaving bosom, with upturned face, with hands locked tight upon the wonder of this hour.

"The rose, the rose has faded, Dione," said the ardent voice. "Look how dead it lies upon my palm! But bend and breathe upon it, and it will bloom again! Ah, that day at Penshurst! when I sought you and they told me you were gone--a brother ill and calling for you--a guardian, no friend of mine, to whose house I had not access! And then the Queen must send for me, and there was service to be done--service which got me my knighthood.... The stream between us widened. At first I thought to span it with a letter, and then I wrote it not. 'Twas all too frail a bridge to trust my hope upon. For what should have the paper said? I am so near a stranger to thee that scarce have we spoken twice together--therefore love me! I am a man who hath done somewhat in the busy world, and shall, God willing, labor once again, but now a cloud overshadows me--therefore love me! I have no wealth or pomp of place to give thee, and I myself am of those whom God hath bound to wander--therefore love me! I chanced upon thee beside a fountain ringed with roses, gray with mist; the sun came out and I saw thee, golden in the golden light--therefore love me! Ah no! you would have answered--I know not what. Therefore I waited, for I have at times a strange patience, a willingness to let Fate guide me. Moreover, I ever thought to meet you, to speak with you face to face again, but it fell not so. Was I with the court, the country claimed you; went I north or west, needs must I hear of you a lovely star within that galaxy I had left. Thrice were we in company together--cursed spite that gave us only time for courtly greeting, courtly parting!"

The voice came nearer, came very near: "Have I said that I wrote not to you? Ay, but I did, my only dear! And as I wrote, from the court, from the camp, from my poor house of Ferne, I said: 'This will tell her how in her I reverence womankind,' and, 'These are flowers for her coronal--will she not know it among a thousand wreaths?' and, 'This, ah, this, will show her how deeply now hath worked the arrow!' and, 'Now she cannot choose but know--her soul will hear my soul cry!' And that those letters might come to your eyes, I, following the fashion, sealed them only with feigned names, altered circumstance. All who ran might read, but the heartbeat was for your ear ... Dione! Didst never guess?"

She answered in a still voice without moving: "It may be that my soul guessed.... If it did so, it was frightened and hid its guess."

"I have told you," said the man. "But, ah, what am I more to you now than on that morn at Penshurst--a stranger! I know not--even you may love another.... But no, I know that you do not. As I was then, so am I now, save that I have served the Queen again, and that cloud I spoke of is overpast. I must go forth to-morrow to seek, to find, to win, to lose--God He knoweth what! I would go as your knight avowed, your favor in my helm, your kiss like holy water on my brow. See, I kneel to you for some sign, some charm to make my voyage good!"

Very slowly the rose-clad maid of honor let fall her gaze from the evening skies to the man before her; as slowly unclasped her hands so tightly locked behind her upraised head. Her eyes were wide and filled with light, her bosom yet rose and fell quickly; in all her mien there was still wonder, grace supreme, a rich unfolding like the opening of a flower to the bliss of understanding. Trembling, her hand went down, and resting on his shoulder, gave him her accolade. She bowed herself towards him; a knot of rosy velvet, loosened from her dress, fell upon the turf beside his knee. Ferne caught up the ribbon, pressed it to his lips and thrust it in the breast of his doublet. Rising, he took her in his arms and they kissed. Her breath came pantingly.

"Oh, I envied her!" she cried. "Now I know that I envied while I blessed her--that unknown Dione!"

"My lady and my only dear!" he said. "Oh, Love is as the sun! So the sunshine bide, let come what will come!"

"I rest in the sunshine!" she said. "Oh, Love is bliss ... but anguish too! I see the white sails of your ships."

She shuddered in his arms. "All that go return not. Ah, tell me that you will come back to me!"

"That will I do," he answered, "an I am a living man. If I die, I shall but wait for thee. I see no parting of our ways."

One hour was theirs. Bread and wine, and flower and fruit, and meeting and parting it held for them. Hand in hand they sat upon the grassy bank, and eyes met eyes, but speech came not often to their lips. They looked and loved, against the winter storing each moment with sweet knowledge, honeyed assurance. Brave and fair were they both, gallant lovers in a gallant time, changing love-looks in a Queen's garden, above the silver Thames. A tide of amethyst fell the sunset light; the swallows circled overhead; a sound was heard of singing voices; violet knight and rose-colored maid of honor, they came at last to say farewell. That night in the lit Palace, amid the garish crowd, they might see each other again, might touch hands, might even have slight speech together, but not as now could heart speak to heart. They rose from the green bank, and as the sun set, as the moon came out, and the singing ceased, and the world grew ashen, they said what lovers say on the brink of absence, and at the last they kissed good-by.

hey were not far north of the Canary Islands, when the sky, which for several days had been overcast, grew very threatening, and the Mere Honour, the Cygnet, the Marigold, and the Star made ready to meet what fury the Lord should be pleased to loose upon them. It came, a maniac unchained, and scattered the ships. Darkness accompanied it, and the sea wrinkled beneath its feet. The ships went here and went there; throughout the night they burned lights, and fired many great pieces of ordnance,--not to prevail against their enemy, but to say each to the other: "Here am I, my sister! Go not too far, come not too near!" Their voices were as whispers to the shouting of their foe; beneath the rolling thunders the sound of cannon and culverin were of less account than the grating of pebbles in a furious surge.

Day came and the storm continued, but with night the wind fell and quiet possessed the deep. The sea subsided, and just before dawn the clouds broke, showing a waning moon. Below it suddenly sprang out two lights, one above the other, and to the Cygnet, safe, though with her plumage sadly ruffled, came the sound of a gun twice fired.

The darkness faded, the gray light strengthened, and showed to the watchers upon the Cygnet's decks the ship in distress. It was Baldry's ship, the little Star. She lay rolling heavily in the heavy sea, her masts gone, her boats swept away, her poop low in the water, her beak-head high, sinking by the stern. Her lights yet burned, ghastly in the dawning; her people, a black swarm upon her forecastle, lay clinging, devouring with their eyes the Cygnet's boats coming for their deliverance across the gray waste. Of the Mere Honour and the Marigold nothing was to be seen.

The swarm descended into the boats, and all pushed off from the doomed ship save a single craft, less crowded than the others, which waited, its occupants gesticulating angry dismay, for the one man who had not left the Star. He stood erect upon her bowsprit, a dark figure outlined against the livid sky.

"IT WAS BALDRY'S SHIP, THE LITTLE STAR"

The watchers upon the Cygnet, from Captain to least powder-boy, drew quick breath.

"Ah, sirs, he loved the Star like a woman!" ejaculated Thynne the master, and, "He swore terribly, but he was a mighty man!" testified the chief gunner. Robin-a-dale swung himself to and fro in an ecstasy of terror. "He rides--he rides so high!" he shrilled. "Higher than the gallows-tree! And he stands so quiet while he rides!"

Upon the poop young Sedley, standing beside his Captain, veiled his eyes with his hand; then, ashamed of his weakness, gazed steadfastly at the lifted figure. Arden, drumming with his fingers upon the rail, looked sidewise at Sir Mortimer Ferne.

"It seems that your quarrel will have to wait some other meeting-place than England," he said. "Perhaps the laws of that terra incognita to which he goes forbid the duello."

"He will not leave our company yet awhile," answered Ferne, with calmness. "As I thought--."

The dark figure had dropped from the bowsprit of the Star into the waiting boat, which at once put after its fellows. Behind the deserted ship suddenly streamed out a red banner of the dawn; stark and black against the color, lonely in the path that must be trod, she awaited her end. To the seafaring men who watched her she was as human as themselves--a ship dying alone.

"All that a man hath will he give for his life," quoth Arden, somewhat grimly, for he was no lover of Baldry, and he was now ashamed of the emotion he had shown.

"To go down with her," said Ferne, slowly,--"that had been the act of a madman. And if to live is a thing less fine than would have been that madness, yet--"

He broke off, and turning from the Star, now very near her death, swept with his gaze the billowing ocean. "I would we might see the Mere Honour and the Marigold," he said, impatiently. "What is lost is lost, and Captain Baldry as well as we must stand this crippling of our enterprise. But the Mere Honour and the Marigold are of more account than the Star."

Out of a cluster of mariners and landsmen rose Robin-a-dale's shrill cry: "She's going down, down, down! Oh, the white figurehead looks no more into the sea--it turns its face to the sky! Down, down, the Star has gone down!"

A silence fell upon the decks of the Cygnet and upon the overfreighted boats laboring towards her. Overhead mast and spar creaked and the low wind sang in the rigging, but the spirit of man was awed within him. A ship was lost, and the sea was lonely beneath the crimson dawn. Where were the Mere Honour and the Marigold, and was all their adventure but a mirage and a cheat? Far away was home, and far away the Indies, and the Cygnet was a little feather tossed between red sky and heaving ocean.

The thought did not last. As the crowded boats drew alongside, up sprang the sun, cheering and warming, and at the Captain's command the musicians of the Cygnet began to play, as at the setting of the watch, a psalm of thanksgiving. Sailors and volunteers, there had been but sixty men aboard the Star, and all were safe. As they clambered over the side, a cheer went up from their comrades of the Cygnet.

The boat that carried Baldry came last, and that adventurer was the latest to set foot upon the Cygnet's deck. Her Captain met him with bared head and outstretched hand.

"We grieve with you, sir, for the loss of the Star," he said, gravely and courteously. "We thank God that no brave man went down with her. The Cygnet gives you welcome, sir."

The man to whom he spoke ignored alike words and extended hand. A towering figure, breathing bitter anger at this spite of Fortune, he turned where he stood and gazed upon the ocean that had swallowed up his ship. Uncouth of nature, given to boasting, a foster-child of Violence and Envy, he yet had qualities which had borne him upward and onward from mean beginnings to where on yesterday he had stood, owner and Captain of the Star, leader of picked men, sea-dog and adventurer as famed for daredevil courage and boundless endurance as for his braggadocio vein and sullen temper. Now the Star that he had loved was at the bottom of the sea; his men, a handful beside the Cygnet's force, must give obedience to her officers; and he himself,--what was he more than a volunteer aboard his enemy's ship? Captain Robert Baldry, grinding his teeth, found the situation intolerable.

Sir Mortimer Ferne, biting his lip in a sudden revulsion of feeling, was of much the same opinion. But that he would follow after courtesy was as certain as that Baldry would pursue his own will and impulse. Therefore he spoke again, though scarce as cordially as before:

"We will shape our course for Teneriffe, where (I pray to God) we may find the Mere Honour and the Marigold. If it please Captain Baldry to then remove into the Mere Honour, I make no doubt that the Admiral will welcome so notable a recruit. In the mean time your men shall be cared for, and you yourself will command me, sir, in all things that concern your welfare."

Baldry shot him a look. "I am no maker of pretty speeches," he said. "You have me in irons. Pray you, show me some dungeon and give me leave to be alone."

Young Sedley, hotly indignant, muttered something, that was echoed by the little throng of gentlemen adventurers sailing with Sir Mortimer Ferne. Arden, leaning against the mast, coolly observant of all, began to whistle,

"'Of honey and of gall in love there is store:

The honey is much, but the gall is more,'"

thereby bringing upon himself one of Baldry's black glances.

"Lieutenant Sedley," ordered Ferne, sharply, "you will lodge this gentleman in the cabin next mine own, seeing that he hath all needful entertainment. Sir, I do expect your company at dinner."

He bowed, then stood at his full height, while Baldry sufficiently bethought himself to in some sort return the salute, even to give grudging, half--insolent acknowledgment of the debt he owed the Cygnet. At last he went below--to refuse the bread and meat, but to drink deep of the aqua vita which Sedley stiffly offered; then to lock himself in his cabin, bite his nails with rage, and finally, when he had stared at the sea for a long time, to sink his head into his hands and weep a man's tears for irrevocable loss.

Of his fellow adventurers whom he left upon the poop, only Mortimer Ferne held his tongue from blame of his insupportable temper, or refrained from stories of the Star's exploits. The Cygnet was under way, the wind favorable, her white and swelling canvas like clouds against a bright-blue sky, the dolphins playing about her rushing prow, where a golden lady forever kept her eyes upon the deep. In the wind, timber and cordage creaked and sang, while from waist and main-deck came a cheerful sound of men at work repairing what damage the storm had wrought. Thynne the master gave orders in his rumbling bass, then the drum beat for morning service, and, after the godly fashion of the time, there poured from the forecastle, to worship the Lord, mariners and landsmen, gunners, harquebusiers, crossbow and pike men, cabin and powder boys, cook, chirurgeon, and carpenter--all the varied force of that floating castle destined to be dashed like a battering-ram against the power of Spain. The Captain of them all, with his gentlemen and officers about him, paused a moment before moving to his accustomed place, and looked upon his ship from stem to stern, from the thronged decks to the topmost pennant flaunting the sunshine. He found it good, and the salt of life was strong in his nostrils. Inwardly he prayed for the safety of the Mere Honour, and the Marigold, but that picture of the sinking Star he dismissed as far as might be from his mind. She had been but a small ship--notorious indeed for fights against great odds, for sheer bravado and hairbreadth escapes, but still a small ship, and not to be compared with the Cygnet. No life had been forfeited, and Captain Robert Baldry must even digest as best he might his private loss and discomfiture. If, as he walked to his place of honor, and as he stood with English gentlemen about him, with English sailors and soldiers ranged before him giving thanks for deliverance from danger, the Captain of the Cygnet held too high his head; if he at that moment looked upon his life with too conscious a pride, knew too well the difference between himself, steadfast helmsman of all his being, and that untutored nature which drove another from rock to shoal, from shoal to quicksand--yet that knowledge, detestable to all the gods, dragged at his soul but for a moment. He bent his head and prayed for the missing ships, and most heartily for John Nevil, his Admiral, whom he loved; then for Damaris Sedley that she be kept in health and joyousness of mind; and lastly, believing that he but plead for the success of an English expedition against Spain and Antichrist, he prayed for gold and power, a sovereign's gratitude and man's acclaim.

Three days later they came to Teneriffe, and to their great rejoicing found there the Mere Honour and the Marigold. The Admiral signalled a council; and Ferne, taking with him Giles Arden, Sedley, and the Captain of the sunken Star, went aboard the Mere Honour, where he was shortly joined by Baptist Manwood from the Marigold, with his lieutenants Wynch and Paget. In his state-cabin, when he had given his Captains welcome, the Admiral sat at table with his wine before him and heard how had fared the Cygnet and the Marigold, then listened to Baldry's curt recital of the Star's ill destinies. The story ended, he gave his meed of grave sympathy to the man whose whole estate had been that sunken ship. Baldry sat silent, fingering, as was his continual trick, the hilt of his great Andrew Ferrara. But when the Admiral, with his slow, deliberate courtesy, went on to propose that for this adventure Captain Baldry cast his lot with the Mere Honour, he listened, then gave unexpected check.

"I' faith, his berth upon the Cygnet liked him well enough, and though he thanked the Admiral, what reason for changing it? In fine, he should not budge, unless, indeed, Sir Mortimer Ferne--" He turned himself squarely so as to face the Captain of the Cygnet.

The latter, in the instant that passed before he made any answer to Baldry's challenging look, saw once again that vision of the other morning--the flare of dawn, and high against it one desperate figure, a man just balancing if to keep his life or no, seeing that for the thing he loved there was no rescue. Say that the doomed ship had been the Cygnet--would Mortimer Ferne have so cheapened grief, have grown so bitter, be so ready to eat his heart out with envy and despite? Perhaps not; and yet, who knew? The Cygnet was there, visible through the port windows, lifting against serenest skies her proud bulk, her castellated poop and forecastle, her tall masts and streaming pennants. The Star was down below, a hundred leagues from any lover, and the sea was deep upon her, and her guns were silent and her decks untrodden.... He was wearied of Baldry's company, impatient of his mad temper and peasant breeding, very sure that he chose, open-eyed, to torment himself from Teneriffe to America with the sight of a prospering foe merely that that foe might feel a nettle in his unwilling grasp. Yet, so challenged, when had passed that moment, he met Baldry's gloomy eyes, and again assured the adventurer that the presence of so brave a man and redoubted fighter could but do honor to the Cygnet.

His words were all that courtesy could desire: if tone and manner were of the coldest, yet Baldry, not being sensitive, and having gained his point, could afford to let that pass. He turned to the Admiral with a short laugh.

"You see, sir, we are yoke-brothers--Sir Mortimer Ferne and I,--though whether God or the devil hath joined us!... Well, the two of us may send some Spanish souls to hell!"

With his yoke-brother, Arden, and Sedley he returned to the Cygnet, and that evening at supper, having drunken much sack, began to loudly vaunt the deeds of the drowned Star, magnifying her into a being sentient and heroical, and darkly-wishing that the luck of the expedition be not gone with her to the bottom of the sea.

"Luck!" exclaimed Ferne at last, haughtily. "I hate the word. Your luck--my luck--the luck of this our enterprise! It is a craven word, overmuch upon the lips of Christian gentlemen."

"I was not born a gentleman," said Baldry, playing with his knife. "You know that, Sir Mortimer Ferne."

"I'll swear you've taken out no patent since," muttered Arden, whereat his neighbor laughed aloud, and Baldry, pushing back his stool, glared at each in turn.

"I know that a man's will, and not a college of heralds, makes him what he is," said Ferne. "I have known churls in honorable houses and true knights in the common camp. And I submit not my destinies to that gamester Luck: as I deserve and as God wills, so run my race!"

"Oh, every man of us knows our Captain's deserving!" quoth Baldry. "Well, gentlemen, on that occasion of which I was speaking, the devil's own luck being with me, I sunk both the carrack and the galley, and headed the Star for the castle of Paria."

On went the wondrous tale, with no further interruption from Sir Mortimer, who sat at the head of the table, playing the part of host to Captain Robert Baldry, listening with cold patience to the adventurer's rhodomontade. When spurred by wine there was wont to awaken in Baldry a certain mordant humor, a rough wit, making straight for the mark and clanging harshly against an adversary's shield, a lurid fancy dully illuminating the subject he had in hand. The wild story that he was telling caught the attention of the more thoughtless sort at table; they leaned forward, encouraging him from flight to flight, laughing at each sally of boatswain's wit, ejaculating admiration when the Star and her Captain fairly left the realm of the natural. One splendid lie followed another, until Baldry was caught by his own words, and saw himself thus, and thus, and thus!--a sea-dog confessed, a gatherer of riches, a dealer of death from the poop of the Star! In his mind's eye the lost bark swelled to a phantom ship, gigantic, terrible, wrapped with the mist of the sea; while he himself--ah! he himself--

"He struck the mainmast with his hand,

The foremast with his knee--"

All that he had been and all that he had done, if man were only something more than man, if devil's luck and devil's power would come to his whistle, if the seed of his nature could defy the iron stricture of the flesh, reaching its height, shooting up into a terrible upas-tree--so for the moment Baldry saw himself. Into his voice came a deep and sonorous note, his black eyes glowed; he began to gesture with his hand, stately as a Spaniard. And then, chancing to glance towards the head of the board, he met the eyes of the man who sat there, his Captain now, whom he must follow! What might he read in their depths? Half-scornful amusement, perhaps, and the contempt of the man who has done what man may do for the yoke-fellow who habitually made claim to supernatural prowess; in addition to the scholar's condemnation of blatant ignorance, the courtier's dislike of unmannerliness, the soldier's scorn of unproved deeds, athwart all the philosophic smile! Baldry, flushing darkly, hated with all his wild might, for that he chose to hate, the man who sat so quietly there, who held with so much ease the knowledge that by right of much beside his commission he was leader of every man within those floating walls. The Captain of the Star struck the table with his hand.

"Ah, I had good help that time! My brother sailed with me--Thomas Baldry, that was master of the Speedwell that went down at Fayal in the Azores.... Didst ever see a ghost, Sir Mortimer Ferne?"

"No," answered Ferne, curtly.

"Then the dead come not to haunt us," said Baldry. "I would have sworn a many had passed before your eyes. Now had I been Thomas Baldry I would have won back."

"That also?" demanded Sir Mortimer. His tone was of simple wonder, and there went round the board a laugh for Baldry's boasting. That adventurer started to his feet, his eyes, that were black, deep-set, and very bright, fixed upon Ferne.

"That also," he answered. "An I should die before our swords cross, that also!"

He turned and left the cabin.

"Now," said Arden, as his heavy footsteps died away, "I had rather gather snow for the Grand Turk than rubies with some I wot of!"

Henry Sedley, a hot red in his cheek, and his dark hair thrown back, turned from staring after the retreating figure. "If I send him my cartel, Sir Mortimer, wilt put me in irons?"

"Ay, that will I," said Ferne, calmly. "Word and deed he but doth after his kind. Well, let him go. For his words, that a man's deeds do haunt him, rising like shadows across his path, I believe full well--but for me the master of the Speedwell makes no stirring.... Take thy lute, Henry Sedley, and sing to us, giving honey after gall! Sing to me of other things than war."

As he spoke he moved to the stern windows, took his seat upon the bench beneath, and leaning on his arm, looked out upon the low red sun and the darkening ocean.

"'Ring out your bells, let mourning shows be spread:

For love is dead:

Love is dead, infected

With plague of deep disdain--'"

sang Sedley with throbbing sweetness, depth of melancholy passion. The listener's spirit left its chafing, left pride and disdain, and drifted on that melodious tide to far heavens.

"'Weep, neighbors, weep; do you not hear it said

That Love is dead?

His death-bed peacock's folly;

His winding sheet is shame;

His will false-seeming wholly;

His sole executor blame!'"

rang Sedley's splendid voice. The song ended; the sun sank; on came the invader night. Ferne took the lute and slowly swept its strings.

"How much, how little of it all is peacock's folly," he said; "who knoweth? Life and Living, Love and Hate, and Honor the bubble, and Shame the Nessus-robe, and Death, which, when all's done, may have no answer to the riddle!--Where is the fixed star, and who knoweth depth from shallow, or himself, or anything?" He struck the lute again, drawing from it a lingering and mournful note.

"Now out upon the man who brought melancholy into fashion!" ejaculated Arden. "In danger the blithest soul alive, when all is well you do ask yourself too many questions! I'll go companion with Robert Baldry, who keeps no fashions save of Mars's devising."

"Why, I am not sad," said Ferne, rousing himself. "Come, I'll dice with thee for fifty ducats and a gold jewel--to be paid from the first ship we take!"

On sailed the ships through tranquil seas, until many days had fallen into their wake, slipping by them like painted clouds of floating seaweed or silver-finned vagrants of the deep. Great calms brooded upon the water, and the sails fell idle, flag and pennant drooped; then the trade-wind blew, and the white ships drove on. They drove into the blue distance, towards unknown ports--known only in that they would surely prove themselves Ports of All Peril. At night the sea burned; a field of gold it ran to horizons jewelled with richer stars than shone at home. Above them, in the vault of heaven, hung the Great Ship, blazed the Southern Cross. Every hour saw the flight of meteors, and their trains, golden argosies of the sky, faded slowly from the dark-blue depths. When the moon arose she was ringed with colors, but the men who gazed upon her said not, "Every hue of the rainbow is there." They said, "See the red gold, the pearls and the emeralds!" The night died suddenly and the day was upon them, an aureate god, lavish of splendor. They hailed him with music; as they pulled and hauled, the seamen sang. Other winds than those of heaven drove them on. High purpose, love of country, religious ecstasy, chivalrous devotion, greed of gain, lust of aggrandizement, lust of power, mad ambitions, ruthless intents--by how strong a current, here crystal clear, there thick and denied, were they swept towards their appointed haven! In cruelty and lust, in the faith of little children and the courage of old demi-gods, they went like homing pigeons; and not a soul, from him who gave command to him who, far aloft, looked out upon the deep, recked or cared that another age would call him pirate or corsair, raising brow and shoulder over the morality of his deeds.

In the realms which they were entering, Truth, shattered into a thousand gleaming fragments, might be held in part, but never wholly. There man's quarry was the false Florimel, and she lured him on and he saw with magically anointed eyes. Too suddenly awakened, the imagination of the time was reeling; its sap ran too fast; wonders of the outer, revelations of the inner, universe crowded too swiftly; the heady wine made now gods, now fools of men. The white light was not for the heirs of that age, nor yet the golden mean. Wonders happened, that they knew, and so like children they looked for strange chances. There was no miracle at which their faith would balk, no illusion whose cobweb tissue they cared to tear away. Give but a grain whereon to build, a phenomenon before which started back, amazed and daunted, the knowledge of the age, and forthwith a mighty imagination leaped upon it, claimed it for its own. There had been but a grain of sand, an inexplicable fact--lo! now, a rounded pearl shot with all the hues of the morning, a miracle of grace or an evidence of diabolic power, to doubt which was heresy!

Adventurers to the Spanish Main believed in devil-haunted seas, in flying islands, in a nation of men whose eyes were set in their shoulders, and of women who cut off the right breast and slew every male child. They believed in a hidden city, from end to end a three days' march, where gold-dust thickened the air, and an Inca drank with his nobles in a garden whose plants waved not in the wind, whose flowers drooped not, whose birds never stirred upon the bough, for all alike were made of gold. They believed in a fair fountain, hard indeed to find, but of such efficacy that the graybeard who dipped in its shining waters stepped forth a youth upon ever-vernal banks.