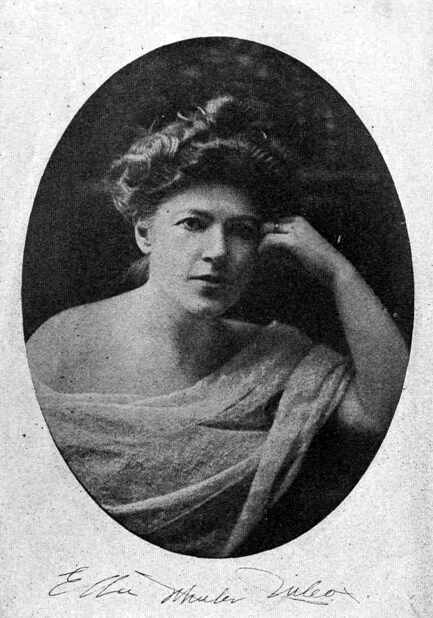

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Woman of the World, by Ella Wheeler Wilcox

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Woman of the World

Her Counsel to Other People's Sons and Daughters

Author: Ella Wheeler Wilcox

Release Date: April 14, 2004 [EBook #12020]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A WOMAN OF THE WORLD ***

Produced by Charles Aldarondo, Joris Van Dael and PG Distributed

Proofreaders

Late Student, Aged Twenty-three

Were you an older man, my dear Ray, your letter would be consigned to the flames unanswered, and our friendship would become constrained and formal, if it did not end utterly. But knowing you to be so many years my junior, and so slightly acquainted with yourself or womankind, I am going to be the friend you need, instead of the misfortune you invite.

I will not say that your letter was a complete surprise to me. It is seldom a woman is so unsophisticated in the ways of men that she is not aware when friendship passes the borderline and trespasses on the domain of passion.

I realized on the last two occasions we met that you were not quite normal. The first was at Mrs. Hanover's dinner; and I attributed some indiscreet words and actions on your part to the very old Burgundy served to a very young man.

Since the memory of mortal, Bacchus has been a confederate of Cupid, and the victims of the former have a period (though brief indeed) of believing themselves slaves to the latter.

As I chanced to be your right-hand neighbour at that very merry board, where wit, wisdom, and beauty combined to condense hours into minutes, I considered it a mere accident that you gave yourself to me with somewhat marked devotion. Had I been any other one of the ladies present, it would have been the same, I thought. Our next and last encounter, however, set me thinking.

It was fully a week later, and that most unromantic portion of the day, between breakfast and luncheon.

It was a Bagby recital, and you sought me out as I was listening to the music, and caused me to leave before the programme was half done. You were no longer under the dominion of Bacchus, though Euterpe may have taken his task upon herself, as she often does, and your manner and expression of countenance troubled me.

I happen to be a woman whose heart life is absolutely complete. I have realized my dreams, and have no least desire to turn them into nightmares. I like original rôles, too, and that of the really happy wife is less hackneyed than the part of the "misunderstood woman." And I find greater enjoyment in the steady flame of one lamp than in the flaring light of many candles.

I have taken a good deal of pride in keeping my lamp well trimmed and brightly burning, and I was startled and offended at the idea of any man coming so near he imagined he might blow out the light.

Your letter, however, makes me more sorry than angry.

You are passing through a phase of experience which comes to almost every youth, between sixteen and twenty-four.

Your affectional and romantic nature is blossoming out, and you are in that transition period where an older woman appeals to you.

Being crude and unformed yourself, the mature and ripened mind and body attract you.

A very young man is fascinated by an older woman's charms, just as a very old man is drawn to a girl in her teens.

This is according to the law of completion, each entity seeking for what it does not possess.

Ask any middle-aged man of your acquaintance to tell you the years of the first woman he imagined he loved, and you will find you are following a beaten path.

Because you are a worth while young man, with a bright future before you, I am, as I think of the matter, glad you selected me rather than some other less happy or considerate woman, as the object of your regard.

An unhappy wife or an ambitious adventuress might mar your future, and leave you with lowered ideals and blasted prospects.

You tell me in your letter that for "a day of life and love with me you would willingly give up the world and snap your fingers in the face of conventional society, and even face death with a laugh." It is easy for a passionate, romantic nature to work itself into a mood where those words are felt when written, and sometimes the mood carries a man and a woman through the fulfilment of such assertions. But invariably afterward comes regret, remorse, and disillusion.

No man enjoys having the world take him at his word, when he says he is ready to give it up for the woman he loves.

He wants the woman and the world, too.

In the long run, he finds the world's respect more necessary to his continued happiness than the woman's society.

Just recall the history of all such cases you have known, and you will find my assertions true.

Thank your stars that I am not a reckless woman ready to take you at your word, and thank your stars, too, that I am not a free woman who would be foolish enough and selfish enough to harness a young husband to a mature wife. I know you resent this reference to the difference in our years, which may not be so marked to the observer to-day, but how would it be ten, fifteen years from now? There are few disasters greater for husband or wife than the marriage of a boy of twenty to a woman a dozen years his senior. For when he reaches thirty-five, despair and misery must almost inevitably face them both.

You must forgive me when I tell you that one sentence in your letter caused a broad smile.

That sentence was, "Would to God I had met you when you were free to be wooed and loved, as never man loved woman before."

Now I have been married ten years, and you are twenty-three years old! You must blame my imagination (not my heart, which has no intention of being cruel) for the picture presented to my mind's eye by your wish.

I saw myself in the full flower of young ladyhood, carrying at my side an awkward lad of a dozen years, attired in knickerbockers, and probably chewing a taffy stick, yet "wooing and loving as never man loved before."

I suppose, however, the idea in your mind was that you wished Fate had made me of your own age, and left me free for you.

But few boys of twenty-three are capable of knowing what they want in a life companion. Ten years from now your ideal will have changed.

You are in love with love, life, and all womankind, my dear boy, not with me, your friend.

Put away all such ideas, and settle down to hard study and serious ambitions, and seal this letter of yours, which I am returning with my reply, and lay it carefully away in some safe place. Mark it to be destroyed unopened in case of your death. But if you live, I want you to open, re-read and burn it on the evening before your marriage to some lovely girl, who is probably rolling a hoop to-day; and if I am living, I want you to write and thank me for what I have said to you here. I hardly expect you will feel like doing it now, but I can wait.

Do not write me again until that time, and when we meet, be my good sensible friend—one I can introduce to my husband, for only such friends do I care to know.

At Vassar College

My dear niece:—It was a pleasure to receive so long a letter from you after almost two years of silence. It hardly seems possible that you are eighteen years old. To have graduated from high school with such honours that you are able to enter Vassar at so early an age is much to your credit.

I indulged in a good-natured laugh over your request for my advice regarding a college course. You say, "I remember that I once heard you state that you did not believe in higher education for women, and, therefore, I am anxious to have your opinion of this undertaking of mine."

Now of course, my dear child, what you wish me to say is, that I am charmed with your resolution to graduate from Vassar. You have entered the college fully determined to take a complete course, and you surely would not like a discouraging or disapproving letter from your auntie.

"Please give me your opinion of my course of action" always means, "Please approve of what I am doing."

Well I do approve. I always approve when a human being is carrying out a determination, even if I am confident it is the wrong determination.

The really useful knowledge of life must come through strong convictions. Strong convictions are usually obtained only on the pathway of personal experience.

To argue a man out of a certain course of action rarely argues away his own beliefs and desires in the matter. We may save him some bitter experience in the contemplated project, but he is almost certain to find that same bitter experience later, because he has been coerced, not enlightened.

Had he gained his knowledge in the first instance, he would have escaped the later disaster.

A college education does not seem to me the most desirable thing for a woman, unless she intends to enter into educational pursuits as a means of livelihood. I understand it is your intention to become a teacher, and, therefore, you are wise to prepare yourself by a thorough education. Be the very best, in whatever line of employment you enter.

Scorn any half-way achievements. Make yourself a brilliantly educated woman, but look to it that in the effort you do not forget two other important matters—health and sympathy. My objection to higher education for women, which you once heard me express, is founded on the fact that I have met many college women who were anaemic and utterly devoid of emotion. One beautiful young girl I recall who at fourteen years of age seemed to embody all the physical and temperamental charms possible for womankind. Softly rounded features, vivid colouring, voluptuous curves of form, yet delicacy and refinement in every portion of her anatomy, she breathed love and radiated sympathy. I thought of her as the ideal woman in embryo; and the brightness of her intellect was the finishing touch to a perfect girlhood. I saw her again at twenty-four. She had graduated from an American college and had taken two years in a foreign institution of learning. She had carried away all the honours—but, alas, the higher education had carried away all her charms of person and of temperament. Attenuated, pallid, sharp-featured, she appeared much older than her years, and the lovely, confiding and tender qualities of mind, which made her so attractive to older people, had given place to cold austerity and hypercriticism.

Men were only objects of amusement, indifference, or ridicule to her. Sentiment she regarded as an indication of crudity, emotion as an insignia of vulgarity. The heart was a purely physical organ, she knew from her studies in anatomy. It was no more the seat of emotion than the liver or lungs. The brain was the only portion of the human being which appealed to her, and "educated" people were the only ones who interested her, because they were capable of argument and discussion of intellectual problems—her one source of entertainment.

Half an hour in the society of this over-trained young person left one exhausted and disillusioned with brainy women. I beg you to pay no such price for an education as this young girl paid. I remember you as a robust, rosy girl, with charming manners. Your mother was concerned, on my last visit, because I called you a pretty girl in your hearing. She said the one effort of her life was to rear a sensible Christian daughter with no vanity. She could not understand my point of view when I said I should regret it if a daughter of mine was without vanity, and that I should strive to awaken it in her. Cultivate enough vanity to care about your personal appearance and your deportment. No amount of education can recompense a woman for the loss of complexion, figure, or charm. And do not let your emotional and affectional nature grow atrophied.

Control your emotions, but do not crucify them.

Do not mistake frigidity for serenity, nor austerity for self-control. Be affable, amiable, and sweet, no matter how much you know. And listen more than you talk.

The woman who knows how to show interest is tenfold more attractive than the woman who is for ever anxious to instruct. Learn how to call out the best in other people, and lead them to talk of whatever most interests them. In this way you will gain a wide knowledge of human nature, which is the best education possible. Try and keep a little originality of thought, which is the most difficult of all undertakings while in college; and, if possible, be as lovable a woman when you go forth into the world "finished" as when you entered the doors of your Alma Mater: for to be unlovable is a far greater disaster than to be uneducated.

During Her Honeymoon

I am very much flattered that you should write your first letter as Mrs. Gordon to me. Its receipt was a surprise, as I have known you so slightly—only when we were both guests under a friend's roof for one week.

I had no idea that you were noticing me particularly at that time, there was such a merry crowd of younger people about you. How careful we matrons should be, when in the presence of débutantes, for it seems they are taking notes for future reference!

I am glad that my behaviour and conversation were such that you feel you can ask me for instructions at this important period of your life. Here is the text you have given me:

"I want you to tell me, dear Mrs. West, how to be as happy, and loved, and loving, after fifteen years of married life, as you are. I so dread the waning of my honeymoon."

And now you want me to preach you a little sermon on this text. Well, my dear girl, I am at a disadvantage in not knowing you better, and not knowing your husband at all.

Husbands are like invalids, each needs a special prescription, according to his ailment.

But as all invalids can be benefited by certain sensible suggestions, like taking simple food, and breathing and exercising properly, and sleeping with open windows or out-of-doors, so all husbands can be aided toward perpetual affection by the observance of some general laws, on the part of the wife.

I am, of course, to take it for granted that you have married a man with principles and ideals, a man who loves you and desires to make a good husband. I know you were not so unfortunate as to possess a large amount of property for any man to seek, and so I can rely upon the natural supposition that you were married for love.

It might be worth your while, right now, while your husband's memory is fresh upon the subject, to ask him what particular characteristics first won his attention, and what caused him to select you for a life companion.

Up to the present moment, perhaps, he has never told you any more substantial reason for loving you than the usual lovers' explanation—"Just because." But if you ask him to think it over, I am sure he can give you a more explicit answer.

After you have found what qualities, habits, actions, or accomplishments attracted him, write them down in a little book and refer to them two or three times a year. On these occasions ask yourself if you are keeping these attractions fresh and bright as they were in the days of courtship. Women easily drop the things which won a man's heart, and are unconscious that the change they bemoan began in themselves. But do not imagine you can rest at ease after marriage with only the qualities, and charms, and virtues, which won you a lover. To keep a husband in love is a more serious consideration than to win a lover.

You must add year by year to your attractions.

As the deep bloom of first youth passes, you must cultivate mental and spiritual traits which will give your face a lustre from within.

And as the mirth and fun of life drifts farther from you, and you find the merry jest, which of old turned care into laughter, less ready on your lip, you must cultivate a wholesome optimistic view of life, to sustain your husband through the trials and disasters besetting most mortal paths.

Make one solemn resolve now, and never forget it. Say to yourself, "On no other spot, in no other house on earth, shall my husband find a more cheerful face, a more loving welcome, or a more restful atmosphere, than he finds at home."

No matter what vicissitudes arise, and what complications occur, keep that resolve. It will at least help to sustain you with a sense of self-respect, if unhappiness from any outside source should shadow your life. An attractive home has become a sort of platitude in speech, but it remains a thing of vital importance, all the same, in actual life and in marriage.

Think often and speak frequently to your husband of his good qualities and of the things you most admire in him.

Sincere and judicious praise is to noble nature like spring rain and sun to the earth. Ignore or make light of his small failings, and when you must criticize a serious fault, do not dwell upon it. A husband and wife should endeavour to be such good friends that kindly criticism is accepted as an evidence of mutual love which desires the highest attainments for its object.

But no man likes to think his wife has set about the task of making him over, and if you have any such intention I beg you to conceal it, and go about it slowly and with caution.

A woman who knows how to praise more readily than she knows how to criticize, and who has the tact and skill to adapt herself to a man's moods and to find amusement and entertainment in his whims, can lead him away from their indulgence without his knowledge.

Such women are the real reformers of men, though they scorn the word, and disclaim the effort.

It is well to keep a man conscious that you are a refined and delicate-minded woman, yet do not insist upon being worshipped on a pedestal. It tires a man's neck to be for ever gazing upward, and statues are less agreeable companions than human beings.

If you wish to be thought spotless marble, instead of warm flesh and blood, you should have gone into a museum, and refused marriage. Remember God knew what He was about, when He fashioned woman to be man's companion, mate, and mother of his children.

Respect yourself in all those capacities, and regard the fulfilment of each duty as sacred and beautiful.

Do not thrust upon the man's mind continually the idea that you are a vastly higher order of being than he is.

He will reach your standard much sooner if you come half-way and meet him on the plane of common sense and human understanding. Meantime let him never doubt your abhorrence of vulgarity, and your distaste for the familiarity which breeds contempt.

It is a great art, when a wife knows how to attract a husband year after year, with the allurements of the boudoir, and never to disillusion him with the familiarities of the dressing-room.

Such women there are, who have lived with their lovers in poverty's close quarters, and through sickness and trouble, and yet have never brushed the bloom from the fruit of romance. But she who needs to be told in what this art consists, would never understand, and she who understands, need not be told.

Keep your husband certain of the fact that his attention and society is more agreeable to you than that of any other man. But never beg for his attentions, and do not permit him to think you are incapable of enjoying yourself without his playing the devoted cavalier.

The moment a man feels such an attitude is compulsory, it becomes irksome. Learn how to entertain yourself. Cling to your accomplishments and add others. A man admires a progressive woman who keeps step with the age. Study, and think, and read, and cultivate the art of listening. This will make you interesting to men and women alike, and your husband will hear you praised as an agreeable and charming woman, and that always pleases a man, as it indicates his good taste and good luck.

Avoid giving your husband the impression that you expect a detailed account of every moment spent away from you. Convince him that you believe in his honour and loyalty, and that you have no desire to control or influence his actions in any matters which do not conflict with his self-respect or your pride.

Cultivate the society of the women he admires. There is both wisdom and tact in such a course.

Wisdom in making an ideal a reality, and tact in avoiding any semblance of that most unbecoming fault—jealousy.

Let him see that you have absolute faith in your own powers to hold him, and that you respect him too much to mistake a frank admiration for an unworthy sentiment. Do not hesitate to speak with equal frankness of the qualities you admire in other men. Educate him in liberality and generosity, by example.

Allow no one to criticize him in your presence, and do not discuss his weaknesses with others. I have known wives to meet in conclaves, and dissect husbands for an entire afternoon. And each wife seemed anxious to pose as the most neglected and unappreciated woman of the lot. With all the faults of the sterner sex, I never heard of such a caucus of husbands.

Take an interest in your husband's business affairs, and sympathize with the cares and anxieties which beset him. Distract his mind with pleasant or amusing conversation, when you find him nervous and fagged in brain and body.

Yet do not feel that you must never indicate any trouble of your own, for it is conducive to selfishness when a wife hides all her worries and indispositions to listen to those of her husband. But since the work-a-day world, outside the home, is usually filled with irritations for a busy man, it should be a wife's desire to make his home-coming a season of anticipation and joy.

Do not expect a husband to be happy and contented with a continuous diet of love and sentiment and romance. He needs also much that is practical and commonplace mingled with his mental food.

I have known an adoring young wife to irritate Cupid so he went out and sat on the door-step, contemplating flight, by continual neglect of small duties.

There were never any matches in the receivers; when the husband wanted one he was obliged to search the house. The newspaper he had folded and left ready to read at leisure was used to light the fire, although an overfilled waste-basket stood near. The towel-rack was empty just when he wanted his bath, and his bedroom slippers were always kicked so far under the bed that he was obliged to crawl on all fours to reach them.

Then his loving spouse was sure to want to be "cuddled" when he was smoking his cigar and reading,—a triple occupation only possible to a human freak, with three arms, four eyes, and two mouths.

Therefore I would urge you, my dear Edna, to mingle the practical with the ideal, and common sense with sentiment, and tact with affection, in your domestic life.

These general rules are all I can give to guide your barque into the smooth, sea of marital happiness.

It is a wide sea, with many harbours and ports, and no two ships start from exactly the same point or take exactly the same course. You will encounter rocks and reefs, perhaps, which my boat escaped, and I have no chart to guide you away from those rocks.

If I knew you better, and knew your husband at all, I might steer you a little farther out of Honeymoon Bay into calm waters, and tell you how to reef your sails, and how to tack at certain junctures of the voyage, and with the wind in certain directions.

But if you keep your heart full of love, your mind clear of distrust, and your lips free from faultfinding, and if you pray for guidance and light upon your way, I am sure you cannot miss the course.

Who Faces the Necessity to Earn a Living

It is indeed a problem, my dear Gladys, to face stern-visaged Necessity after walking with laughing-lipped Pleasure for twenty-two years.

What an unforeseen event that your father should sink his fortune in a rash venture and die of remorse and discouragement scarcely six months after you were travelling through Europe with me, and laughing at my vain attempts to make you economize.

You have acted the noble and womanly part, in using the last dollar of your father's property to pay his debts, and I could imagine you doing no other way.

But now comes the need of earning a livelihood for yourself, and your delicate mother.

I know you have gone over the list of your accomplishments and taken stock of all your inherited and acquired qualities. You play the piano well, but in these days of Paderewskies and pianolas, no one wants to employ a young girl music-teacher. You do not sing, and if you did, that would not afford you a means of support. The best of natural voices need a fortune spent before half a fortune can be earned.

You dance like a fairy, and swim like a mermaid, and ride like an Indian princess, but these accomplishments are not lucrative, save in a Midway Plaisance or a Wild West show. You are well educated and your memory is remarkable. You have a facility in mathematics, and your knowledge of grammar and rhetoric will, as you say, enable you to pass the examination for a teacher in the public schools after a little brushing up and study. Then, with the political influence of your father's old friends, you will no doubt be able to obtain a position.

I recollect you as surpassingly skilful with the needle. I know you once saw a charming morning gown in Paris which I persuaded you not to buy at the absurd price asked for it, after the merchant understood we were Americans. And I remember how you passed to another department, purchased materials, went home to our hotel, and cut and made a surprising imitation of the gown at one-tenth the cost.

Why have you not considered turning this talent to account? Though the world goes to war and ruin, yet women will dress, and the need of good seamstresses ever exists.

Go to some enterprising half-grown Western or interior Eastern town, announce yourself in possession of all the Paris styles (as you are), and launch out. Increase your prices gradually, and go abroad on your savings at the end of a year, then come back with new ideas, a larger stock, and higher prices.

You will be on the road to fortune, and can retire with a competence before you are middle-aged. A little skill with the scissors and needle, lots of courage and audacity, and original methods will make a woman succeed in this line of endeavour.

But why do I not approve of the profession upon which you have almost decided—that of teaching—you ask.

I will tell you why.

Next to motherhood, the profession of teacher in public or private schools is the most important one on earth.

It is, in a certain sense, more responsible than that of motherhood, since the work of poor and bad mothers must be undone by the teacher, and where the mother has three or four children for a period of years to influence, the teacher has hundreds continually. There are very few perfect teachers. There are too few excellent ones. There are too many poor ones. I do not believe you possess the requisites for the calling.

A teacher should first of all love children as a class. Their dependence, their ignorance, their helplessness, and their unformed characters should appeal to a woman's mind, and make her forget their many and varied faults and irritating qualities. You like lovable, well-bred, and interesting children, but you are utterly indifferent to all others. You adore beauty, and an ugly child offends your taste. A stupid child irritates you.

You have a wonderful power of acquiring and remembering information, but you do not possess the knack of readily imparting it. You expect others to grasp ideas in the same way you do. This will make you unsympathetic and impatient as a teacher. You have no conception of the influence a teacher exerts upon children in public schools. You were educated in private schools and at home, I know. I attended the country public school, and to this day I can recall the benefits and misfortunes which resulted to me from association with different teachers. Children are keenly alive to the moods of teachers and are often adepts in mind-reading.

A teacher should be able to enter into the hearts and souls of the children under her charge, and she should find as great pleasure in watching their minds develop as the musical genius in watching a composition grow under his touch.

An infinite number of things not included in the school routine should be taught by teachers. Courtesy, kindness to dependents and weaker creatures, a horror of cruelty in all forms, a love of nature, politeness to associates, low speaking and light walking, cleanliness and refinement of manner,—all these may be imparted by a teacher who loves to teach, without extra time or fatigue. I fear a proud disdain, and a scarcely hidden disgust, would be plainly visible in your demeanour toward the majority of the untrained little savages given to your charge in a public school. You have not the love of humanity at large in your heart, nor the patience and perseverance to make you take an optimistic view in the colossal work of developing the minds of children. Therefore it seems to me almost a sin for you to undertake the profession merely because you need to earn a living. There are other things to be considered besides your necessities. Fond as I am of you, I have the betterment of humanity at my heart, too, and cannot feel it is right for you to place yourself in a position where you will not be doing the best for those dependent upon you that could be done.

I have given up hope of seeing mothers made to realize their responsibilities. But I still have hope of the teachers. On them and their full understanding of all it is in their power to do, lies the hope of the world.

Therefore, my dear girl, I urge you to take up dressmaking or millinery instead of school-teaching.

If you ruin a piece of goods in the making, you can replace it and profit by your error. But if you mar a child's nature in your attempt to teach him, you have done an irreparable injury not only to him but to humanity.

If you saw a design started by a lace-maker, you would not think of taking the work and attempting to complete it until you had learned the art of lace-making.

Just so you ought not to think of developing the wonderful intricacies of a child's mind until you have learned how.

It is all right to deliberately choose a vocation which gives us contact only with inanimate things, but we have no right to take the handling of human souls unless we are specially fitted for the task.

Regarding His Sister's Betrothal

Your request, my dear Clarence, that I try to influence your sister to change her determination in this matter, calls for some very plain statements from me.

I have known you and Elise since you were playing with marbles and rattles, and your mother and I have been very good acquaintances (scarcely intimate enough to be called friends) for more than a score of years. You are very much like your mother, both in exterior appearance and in mind. Elise is the image of her father at the time he captured your mother's romantic fancy, and as I recollect him when he died.

You were five years old, Elise three, at that time. Your mother lived with your father six years in months, an eternity in experience. You know that she was unhappy, and that he disillusioned her with love, and almost with life. He married your mother solely for her fortune. She was a sweet and beautiful girl, of excellent family, but your father had no qualities of mind or soul which enabled him to appreciate or care for any woman, save as she could be of use to him, socially and financially.

In six years he managed to dispose of all but a mere pittance of her fortune, and humiliated her in a thousand ways besides. His only decent act was to die and leave her undisturbed for the remainder of her life. Your uncle assisted in her support and saved the remnant of her property, so that she has, by careful and rigorous economy, been able to educate you and Elise, and keep up a respectable appearance in a quiet way.

Of course it was impossible to retain her place among the associates of her better days, and you know how bitter this fact has always made Elise. Your sister has the physical beauty and the overwhelming love of money and power which characterized your father. She has a modicum of your mother's sense of honour, but has been reared in a way not calculated to develop much strength of character. Your mother has been a slave to your sister. Elise is incapable of a deep, intense love for any man, and your mother's pessimistic ideas of love and marriage have still further acted upon her brain cells and atrophied whatever impulses may have been latent in her nature, to love and be loved. These qualities might have been developed had Elise been under the tutelage of some one versed in the science of brain building, but your mother, like most mothers, was not aware of the tremendous possibilities within her grasp, or of the effect of the ideas she expressed in the hearing of her children. Neither did she seem to recognize the father's traits in Elise, and undertake the work of eliminating them, as she might have done. She has been an unselfish and devoted mother, and has made too many sacrifices for Elise. At the same time, she has awakened the mind of your sister to ideals of principle and honour which will help her to be a better woman than her inheritance from your father would otherwise permit. But now, at the age of twenty-one, it is impossible to hope that she will develop into a self-sacrificing, loving, womanly woman, whose happiness can be found in a peaceful domestic life. She has seen your mother sad and despondent, under the yoke of genteel poverty, and heard her bemoan her lost privileges of wealth and station. This, added to her natural craving for money and place, renders a wealthy marriage her only hope of happiness on earth.

Mr. Volney has an enormous fortune. He is, as you say, a senile old man in his dotage. As you say again, such a marriage is a travesty. But Elise is incapable of feeling the love which alone renders marriage a holy institution. She has undesirable qualities which ought not to be transmitted to children, and she is absolutely devoid of maternal instincts.

I have heard her say she would consider motherhood the greatest disaster which could befall her. But she is unfitted for a self-supporting career, and she wants a home and position.

She has beauty, kind and generous impulses, and a love of playing Lady Bountiful. It is not so much that she wants to benefit the needy, as that she likes to place people under obligations and to have them look up to her as a superior being.

Old Mr. Volney is a miser, and his money is doing no one good. He has only distant relatives, and by taking Elise for a wife (according to law) he will wrong no one, and she will make much better use of his fortune than his heirs would make.

Your mother will be relieved of worry and care. Many worthy poor people and charities will receive help, and Elise will have her heart's desire—fine apparel, jewels, a social position, and no one to bother her. The valet and nurse will look after Mr. Volney, and his simple old heart will bask in the pride of an old man—the possession of a pretty young wife.

Had he full use of his mental faculties, and did he long for love and devotion, I would try and dissuade Elise from the marriage, but solely on his account, not on hers.

The young man you mention, as your choice of a suitor for the hand of your sister, might better go up in a balloon to seek for Eutopia than to expect happiness as her husband. He has a sweet, gentle, loving nature, a taste for quiet home joys, fondness for children, and he has two thousand a year, with small prospects of more in the near future.

He should marry a modest, domestic girl, with tastes similar to his own, and with no overweening ambitions. Elise would simply drive him mad in a year's time, with her restless discontent, her extravagance, and her desire for the expensive pleasures of earth. It is useless to reason with her, or to expect her to model her ideas to suit her circumstances. Inheritance and twenty-one years of wrong education must be taken into consideration. What would mean happiness for many women would mean misery for her. I can imagine no more dreadful destiny than to be tied to a senile old man by a legal ceremony, even were I given his millions in payment. But that will mean happiness to Elise.

I think we should let people seek their own ideals of happiness, when they break no law, and injure no other life by it.

I shall congratulate Elise by this post on having made so fortunate an alliance. I could not congratulate her were she to marry her young suitor. I shall congratulate your mother on having nothing to worry about, regarding the future of Elise.

And I advise you to take a philosophical view of the situation, and to remember that, in judging the actions of our fellow beings, we must take their temperaments, characteristics, and environment into consideration, not our own.

You have made the very common error of thinking, because Elise is a handsome young girl, that love, and home, and children would mean happiness to her.

Women vary as greatly as do plants and flowers in their needs. The horticulturist knows that he cannot treat them all alike, and he studies their different requirements.

To some he gives moisture and sun, to some shade, and to some dry, sandy soil. The thistle pushes forth a gorgeous bloom from an arid bed. It would die in the pond where the lily thrives.

Too much sentiment is wasted in this world and too much effort expended in trying to make all people happy in some one way.

When I was a little girl, a Sunday-school superintendent presented every girl in the class with a doll, and each doll was exactly the same. Most little girls like dolls, but I never played with one, as they were always so hopelessly inanimate. If the good man had given me a sled, or a book, or a picture, I would have been happy. As it was, his gift was a failure. You want to present your sister with a devoted young husband, a cottage, and several children, because you think every woman should possess these things. Your sister happens to be one who prefers a wealthy old invalid.

Let her have what she wants, my dear Clarence, and let her work out her destiny in her own way. She will do less harm in the world than if you forced her into your way. Now you must remember that you asked me to help you in this matter, and I could only write you the absolute facts of the situation, as I knew it to be. I feel fairly confident that you will accept my point of view, and act as best man at your sister's wedding.

Shop Girl, Concerning Her Oppressors

Your letter has been destroyed, as you requested, and you need not fear my betraying your confidence.

Your mother was so long in my employ that I feel almost like a foster-mother to you, having seen you grow up from the cradle to self-supporting young womanhood.

The troubles and evils which you mention as existing about you, I know to be quite universal in all large shops, factories, and department stores, indeed in all houses where the two sexes are employed.

I know that a certain order of men in power use that power to lower the ideals and standards of womanhood when they can.

A pretty young girl once in my service related to me the cold-blooded suggestions made to her by her employer to increase the miserable wage paid her in a sweat-shop.

The sacrifice of her virtue seemed no more to this man than the sale of an old garment.

The girl did not make the sacrifice, however, and she did not starve, freeze, or die. She managed to exist and to better her condition by doing domestic work and saving her money to fit herself for more congenial employment. When I last saw her she was planning to become a trained nurse, and had paid for a course of instruction in massage. I tell you this merely to illustrate a fact I fully believe, that any girl who is determined to live an honourable life and retain her self-respect can make her way in the world and rise from lesser to higher positions, if she is patient and willing to do what is termed menial work as a stepping-stone. You tell me that scores of girls are kept in poorly paying, inferior positions when capable of filling better places, simply because they will not accept the dishonourable attentions of some of the men in authority.

You beg me to arouse the good women of America to a crusade against what you say is a growing evil and to boycott such shops and stores.

But you ask me to do what is an impracticable thing.

You would not like to be called as a witness were this matter brought before the courts. Were all the good women of America to begin such a crusade, where would they obtain the proofs of their accusations?

And even if the witnesses were ready, there is not a newspaper in the land that would dare champion the reform. And no great reform can be made without the aid of the press. The daily papers, as you say, give columns to protests against lesser evils, but you must know that these newspapers are largely supported by the profitable advertisements of manufactories and dry-goods houses. Glance over the columns of any of our large dailies and see how much space such advertising occupies.

Imagine what it would mean to lose all this high-priced patronage. Therefore, even if the most moral of editors knew that these establishments were undermining our social conditions and invading our homes, I doubt if he could be induced to make a protest. It is a curious thing to see how many are the kinds of victims caught and held in the clutches of the money-devil-fish in our wonderful land of freedom.

Even clergymen who are preaching morality and brotherly love are compelled to keep their mouths shut on certain evils and abuses, lest they offend the pillars of the church and deprive the treasury of its income.

In a certain New England town famous for its educational institution, a clergyman denounced a corporation which had swindled the poor and deceived scores of citizens. He was requested to discontinue further references to the matter, as the church treasury was supplied by the money which accrued from this monopoly.

The most powerful members of the church were officers in the corporation.

The young clergyman sent in his resignation and gave up an assured salary to follow the light of his own conscience. But there are few with his bravery and, therefore, the strongholds of selfishness and self-indulgence remain impregnable. While we admire the splendid character which makes a man capable of refusing a salary which means hush-money, we can at the same time understand the difficult position of a clergyman with a hungry brood of children to support, who hesitates at such a move. We can understand how he argues with himself, that by taking the money of the monopolists, he is able to do more good for humanity than by refusing it, and losing both influence and income. It is a false argument, yet the worn and weary mind of the average orthodox minister will accept it as the advisable course to pursue. So you will see how difficult is the task you suggest my undertaking. You tell me that it is useless for you to leave one shop and go to another, as all are more or less conducted on the same lines; and that it is mere chance if a girl finds herself in a position where she can advance on her merits. Even then a sudden change in heads of departments some day may destroy all her hopes.

You say I have no idea how many girls go wrong just through the persecution and tyranny of these men—forced to fall in order to keep herself fed and clothed. I repeat what I said already in this connection,—that I am certain any girl determined to keep herself above reproach and ambitious to rise in the world can do so. She may have to endure many privations and sorrows for a time, and that time may seem long and weary, but a change will come for the better as surely as spring follows winter, if she does not waver.

If you will look carefully into the facts of the cases which fall under your observation, I am confident you will see that it is vanity and indolence, not hunger and oppression, which cause the majority of the girls you mention to go astray. They desire to make as good an appearance, and to be given the same privileges of leisure, as the favourite who has been promoted through unworthy methods.

You tell me you would rather jump from Brooklyn Bridge and end the struggle at once than lose your self-respect, but that you are weary of seeing the girls with less conscience, and lesser capabilities, pushed ahead of you and your worthy associates. Yet I am certain from the tone of your letter that you will never forget your self-respect, and I have faith that you can make your way in the world in spite of all the designing masculine oppressors in existence.

So will any woman, who sets her mark high, and believes in the invincible power of her own spirit to conquer all the demons of earth.

Do not imagine your position is one of unusual trial and temptation. A young actress of my acquaintance has been obliged to fight her way slowly to partial recognition because she would not accept the conditions offered, with leading rôles and fine wardrobe, by two polygamous-minded managers.

She is making her way, however, and the very battle she is fighting with life has strengthened her powers as an artist. A young stenographer has been compelled to give up two positions because she would not allow the loverlike attentions of married employers. She was called a silly prude and discharged. Yet she is occupying an excellent position with a clean high-class business house to-day.

Domestics are sometimes driven from private homes by the same pursuit of the employer. Men are only in a state of evolution, and the animal instincts are still strong in them. The world has allowed them so much license, and society has been so lenient with their misdeeds, that it has been difficult for them to practise self-control and aspire to a higher standard. You must be sorry for them and do what you can to help them understand the worth and value of true womanhood. Never for one instant believe that you can be hindered by the machinations of a few unworthy men, from reaching any goal you set.

One good, intelligently virtuous woman, determined to make the most of her capabilities by fair methods, can overcome a whole army of self-indulgent, sensual men, and compel them to doff their hats to her. I am always deeply sympathetic toward the girl who is tempted through her emotions, or her affections, to forget herself. But I have no great pity for the woman who sells herself. There are always charitable societies, and there are always menial labours to do, and either door of escape from the sale of honour would be sought by the girl of right ideals. It is a bitter experience to see the woman who has stepped down into the soil of life flaunting her finery and her power in the face of virtue. But look about you and see how soon the finery becomes tatters—how soon the power is transferred to another.

Woman's position in the world is growing better, brighter, and more independent with each year. There are more avenues open to her—larger opportunities waiting for the employment of her abilities. She has tried a thorny path for centuries, but she has small reason to despair of her outlook to-day.

Each woman must fight her battle alone, and walk by the light from within.

The world gives her only a superficial protection, either through its courts or its society.

Men demand virtue from woman and endeavour in every way to lead her away from its path.

But the divinity within her can carry her to the heights, if she will not be lured by the voice of the senses, or frightened by the demands of the appetite, or debased by the mercenary spirit of the age.

Go on in your brave determination to lead a sensible and moral life, my dear girl, and let your example be a guide to others, and prove that woman may succeed on the right basis if she will, in spite of temptations and oppressions.

After Three Years as a Teacher

The way you took my frank criticisms and doubts of your ability to make a good school-teacher, proves you to be a girl of much character. Your success proves, too, that given the general qualifications of a fairly capable and educated human being, add concentration and will, and we can achieve wonders in any line of work we undertake. I am still of the opinion that no woman of my acquaintance was more wholly unfit to teach young children, as they should be taught, than your fair self as I last knew you.

I take pride in believing that my heroic methods were what brought out the undeveloped qualities you needed to ensure such success.

There are certain natures that need to be antagonized before they do their best. Others are prostrated and robbed of all strength by a criticism or a doubt.

You have realized this, I am sure, in your experiences with pupils. "You cannot do it" is a more stimulating war-cry to some people than "You can." And to such the sneer of the foe does more good, than the smile of the friend. A phrenologist would tell us that strongly developed organs of self-esteem and love of approbation accompanied this trait of character.

I am sure it proves to be the case with you.

Brought up as you were, the only child of indulgent parents, and given admiration and praise by all your associates, you could hardly reach the age of twenty-two without having developed self-esteem and love of praise. You were naturally brighter than most of your companions. (They were also children of fortune, as the term goes, but to my idea the children reared in wealth, are usually children of misfortune. For the real fortune of life is to encounter the discipline which brings out our strongest qualities.)

Your father was a poor boy, who fought his way up to wealth and power before you were born; but he unfortunately wanted the earth beside, and so died in poverty after staking all he had, which was enough, to make more, which he did not need.

You inherit much of his force of character, and that is what gave you the reputation of extreme cleverness among your more commonplace companions. Compared with the really brilliant and talented people of earth, you are not clever. That is why I found you so companionable and charming, no doubt; for the brilliant people—especially women—are rarely companionable for more than a few hours at a time. I gave you that supreme test of friendship—the companionship of travel for a period of months. And I loved you better at the end of the time than at the beginning.

I have often thought how much less occupation there would be for the divorce courts and how many more "indefinitely postponed" announcements of engagements would result from an established custom of a pre-betrothal trip!

If a young man and woman who were enamoured could travel for two or three months, with a chaperon (in the shape of a mother-in-law or two), the lawyers would lose much profit; but I fear race suicide might ensue. Nothing, unless it is the sick-room or the card-table, brings out the real characteristics of human beings like travel.

The irritating delays of boats and trains, and the still more irritating unresponsiveness of officials, when asked the cause, will test the temper and the patience of even a pair of lovers. It is not surprising if the traveller does lose both at times, but it is admirable if he does not. I remember how adorable you were, while I was a bundle of dynamite, ready to explode and send the stolid, uncommunicative conductor and brakemen into a journey through space, when we suffered that long delay coming from California. It is due the travelling public to explain such delays, but the railroads of America have grown to feel that they owe no explanation to any one, even to God, for what they do or do not. While I lost vitality and composure by such idle reflections, you were amusing the nervous travellers by your bright bits of narrative and ready repartee. That fortunate fellow you have promised to marry at the end of two years has no idea what a charming companion he will find in you for travel.

It is interesting to have you say you feel that you need two more years as a teacher, before you are fully developed enough to take up the responsibilities of marriage. You will be twenty-seven then:—that is the age at which the average American girl begins to be most interesting, and the age when she is first physically mature.

And your children will be more fully endowed mentally than if you had become a mother in your teens.

As a rule the brainy people of the world are not born of very youthful parents; you will find youth gives physique, maturity gives brains to offspring.

I did not quite finish my train of reasoning about your self-esteem.

It was because you had always believed yourself to be capable of doing anything you undertook to do, that you were roused by my assertion that you could not make a good school-teacher, to attempt it. I hurt your pride a bit, and you were determined to prove me wrong. Had you been self-depreciating and oversensitive, what I said would have turned you from that field of effort. And that would have been a desirable result, since one who can be turned from any undertaking ought to be.

I still think the world has lost a wonderful artist by your not entering the lists of designers and dressmakers. But since my recital of the faults which would prevent your success as a teacher led you to overcome them, I am proud and glad, that you have gone on in the work you contemplated. Good teachers are more needed than good dressmakers.

And you are sweet and charming as usual, to tell me that your popularity with children and parents, is greatly due to that letter of mine.

What you write me of the young girl who is making you so much trouble by her jealousy of all other pupils, interests and saddens me. Her devotion to you is of that morbid type, so unwholesome and so dangerous to her peace, and the peace of all her associates. It is a misfortune that mothers do not take such traits in early babyhood, and eradicate them by patient, practical methods. Instead, this mother, like many others, seems to think her little girl should be favoured and flattered because of her morbid tendency.

She mistakes selfishness, envy, greediness, and hysteria for a loving nature.

I can imagine your feelings when this mother told you with a proud smile, "Allie always wants the whole attention of any one she loves, and cannot stand sharing her friends. She was always that way at home. We never could pet her little brother without her going into a spasm. And you must be careful about showing the other children attention before her. It just breaks her heart—she is so sensitive."

Oh, mothers, mothers, what are you thinking about, to be so blind to the work put in your hands to do?

You have little time comparatively to work upon this perverted young mind: but under no conditions favour her, and, no matter what scenes she makes, continue to give praise and affection to the other children when it is their due. The prominence of her parents in the neighbourhood, and the power her father wields in the school board, need not worry you. Go ahead and do what is best for the child and for the school at large. Never deviate one inch from your convictions. Take Allie some day to a garden where there are many flowers, and talk to her about them. Speak of all their different charms, and gather a bouquet. Then say to her, "Now, Allie, you and I love each of these pretty flowers, and see how sweetly they nestle together in your hand. Not one is jealous of the other. Each has its place, and would be missed were it not there. The bouquet needs them all. Just so I need all the dear children in my school, and just so I would miss any one. It makes me ashamed to think any little girl is more selfish and unreasonable than a plant, for little girls are a higher order of creation, and we expect more of them than we expect of plants or of animals. All are parts of God, but the human kingdom is the highest expression of the Creator.

"When you show such jealousy of other children I lose respect for you, and cannot love you as much as I love them. When you are gentle and good, and take your share of my love and attention, and let others have their share, then I am proud of you and fond of you. Suppose one plant said to the sunlight that it must have all the sun, would not that be ridiculous and selfish?"

I would make frequent references to this idea when alone with her, and indeed it would serve as an excellent subject for a talk to all your pupils some day. Then try and make Allie understand how unbecoming and unlovable jealousy is, and how it renders a man or woman an object of pity and ridicule to others.

Praise the people you know who are liberal and broad, and absolutely ignore her moods when in school.

Perhaps in time you can do a little toward awakening her mind to a more wholesome outlook.

What you tell me of her hysterical devotion to one of her classmates, makes me realize that the girl needs careful guidance.

You should talk to her mother, and warn her against encouraging such conditions of mind in her child.

Urge her to keep the girl occupied, and to give her much out-door life, and to teach her that pronounced demonstrations of affection are not good form between young girls. The mother should be careful what books she reads, and should see that she makes no long visits to other homes and receives no guests for a continued time. The child needs to cultivate universal love, not individual devotion.

Ideals, principles, ambitions, should be given the girl, not close companions, for her nature is like a rank, weedy flower that needs refining and cultivating into a perfected blossom.

All this needs a mother's constant care and tact and watchfulness. It is work she should have begun when her little girl first indicated her unfortunate tendencies.

It is late for you to undertake a reconstruction of the misshapen character, but you may be able to begin an improvement, and if you can obtain the mother's cooperation the full formation may be accomplished.

And do not fail to use mental suggestion constantly, and to help the child by your assertions to be what you want her to become. Dwell in conversation with her and in her presence, upon the lovableness and charm of generosity of spirit in general, rather than on the selfishness you observe in herself.

At her least indication of an improvement, give her warm praise. Be careful about bestowing caresses upon her, as she needs to be guarded against hysteria, I should judge from your description. To some children they are the sunlight, to others miasma.

Think of yourself as God's agent, given charge of his unfinished work, and recognize the unseen influences ready to aid you with suggestion and courage when you appeal to them.

Who Has Become Interested in the Metaphysical Thoughts of the Day

Your letter bubbled with enthusiasm, and steamed with optimism. I am rejoiced that you have come into so healthful a line of thought, for I know of no one who was in more immediate need of it than you, when we last met.

As your hostess, I could not tell you how wearing to the nerves your continual reverting to your physical ills became: and I hope I did not seem wholly unsympathetic to you when I so frequently made the effort to change the conversation to more cheerful topics.

And now you tell me that you are astounded to find how universal is this topic with all classes, and on all occasions when one or two human beings gather together even in "His name." Your recital of the church sewing-bee, where all the good Christian women described their diseases and the different operations they and their friends had undergone, is as amusing as it is distressingly realistic.

What a pity that the old theology fostered the idea that God especially loved the people he afflicted with illness and poverty and trouble! It has filled the world with egotistical and selfish invalids and idlers, who have believed they were "God's chosen ones," instead of realizing that they were the natural results of broken laws, which might be mended by the aid of the God-power in themselves, once they understood it.

How Christians have reconciled the idea of a God of love with a God who wanted his chosen ones to be sick and poor, is a problem I cannot solve.

Of course you are well, and growing stronger daily, now that you realize the fact that God made only health, wealth, and love, and that he intended all his children to share his opulence.

As soon as the mind is filled with a dominating idea, no lesser ones can find lodgment therein.

A woman of my acquaintance suffered agonies from seasickness.

She crossed the ocean twice each year, yet seemed unable to accustom herself to the experience.

On her last voyage her child fell dangerously sick with typhoid fever on the second day out at sea.

So wrought up was the mother, and so filled with the thought of her child, that she never felt one moment's seasickness. Her mind was otherwise occupied.

Now you have filled your mind with a consciousness of your divine right to health and happiness, and the thought of sickness and disease has no room.

Yet do not be discouraged if you feel the old ailments and indispositions returning at times. A complete change in mental habits, is difficult to obtain in a moment.

Be satisfied to grow slowly. A wise philosopher has said, "It is not in never falling that we show our strength, but in our ability to rise after repeated falls, and to continue our journey in triumph."

Avoid talking your belief to every individual you meet. It will be breaking your string of pearls for the feet of swine to tread upon. Those who are ready for these truths will indicate the fact to you, and then will be your time for speech. And when you do speak, say little, and say it briefly and to the point.

Leave some things for other minds to study out alone. The people who are not ready for higher ideals of religion and life, will only ridicule or combat your theories and beliefs, if you force them to listen.

Wait until you have fully illustrated by your own conduct of life, that you have something beside vague theories to prove your statements of the power of the mind to conquer circumstance. The world is full to-day of bedraggled and haggard men and women, who are talking loudly of the power of mind to restore youth and health, and bestow riches and success.

Do not add yourself to the unlovely and tiresome army of talkers, until you prove yourself a doer.

And even after you have shown a record of health and prosperity and usefulness, let your silent influence speak louder than your uttered words.

The moment a philosopher becomes a bore, he ceases to be a philosopher.

Concerning His Education and His Profession

My Dear Nephew:—I have considered your request from all sides, and have resolved to disappoint you. This seems to me the kindest thing I can do under the circumstances.

You have gone through two years of college life, and I am sure you are not an ignoramus. Most of the great men of the world's history have enjoyed no fuller educational advantages. To lend you money to finish the college course, would be to help you to start life at the age of twenty-two under the burden of debt. If you are determined to finish a college course, and feel that only by so doing will you equip yourself for the duties of life, I would advise you to drop out for a year and teach, or go into any kind of work which will enable you to earn enough to proceed with your studies. However hard and however disappointing this advice seems to you, I know it suggests a course which will do more for your character than all the money I could lend you.

Aside from the fact that you would begin life with a debt, is the possibility of your contracting the debt habit.

One man in a thousand who borrows money to help himself along in early life is benefited by it.

The other 999 are harmed.

To do anything on another's money is to lean on the shoulder of another instead of walking upright. It is not good calisthenic exercise.

A few years ago I would have acceded to your request.

But each year I live I realize more and more that lending money is the last method to be used in helping people to better themselves. In almost every case where I have lent money, I have lived to regret it. Not because I lost my money (which has usually been the fact), but because I lost respect for my friends.

I remember the case of a young newspaper man and author, who came to me for the loan of five dollars. I had never seen him before, but I knew his brother, a brilliant playwright, in a social way.

The young man told me he had met with a series of disasters on the voyage to New York, and was stranded there absolutely penniless, although money would come at almost any hour from his brother.

Besides this, he showed me letters from editors who had taken work which would be paid for on publication.

"I do not know any one here," the young man said, "and to-day, when I used my last twenty-five cents, I thought of you in desperation.

"Your acquaintance with my brother would serve as an introduction, I felt, and I was confident you would realize my straits when I told you my errand."

Of course I lent the young man five dollars. "I am sure it must be a great humiliation for you to ask for this," I said, "and I am certain you will repay it, though many former experiences have made me question the memory of friends and strangers to whom I have been of similar assistance."

One week later the young man called to tell me he had not been able to do more than keep himself sustained at lunch-counters since he called, but hoped soon to obtain a position on a daily newspaper.

That was ten years ago. The young man sat in an orchestra chair the other night at the theatre directly in front of me, and his attire was faultlessly up to date. From the costume of his companion, I should judge their carriage waited outside.

The young man did not seem to recognize me, and no doubt the incident I mention has escaped his memory.

In all probability I was but one of a score of people who helped him with small loans. Had the young man had been forced to appeal to the society organized in every city for aiding the deserving poor, by being sent disappointed from my door, the ordeal would have so hurt his pride, that he might not have become the professional borrower he undoubtedly is.

I could relate innumerable cases of a similar nature. One man, who was a fashionable teacher of French among the millionaires of New York for several seasons, appealed to me at a time of year when all his patrons were out of the city for a loan to enable him to give his wife medical treatment.

He was to repay it in the autumn. Instead, he came to me then with a much more distressing story of immediate need and seeming proof of money coming to him in a few months. To my chagrin, the loan I advanced was employed in giving a feast to friends at his daughter's wedding, after which he obliterated himself from my vision.

Financial aid lent a woman who soon afterward circled Europe, brought no reimbursement. Her handsomely engraved card, with the "Russell Square Hotel, London," as address, reached me instead of the interest money which perhaps paid the engraver.

Money lent a young man to start a small business, was used for his wedding expenses, and an interval of five years brings no word from him. Poor and despicable beings indeed, become the victims of the borrowing habit. It is the shattered faith in humanity, and the heart hurts that I regret, rather than the loss of what can be replaced. I tell you these incidents that you may realize how I have come to regard money-lending, as a species of unkindness to a friend or relative.

It is only one step removed from giving a sick or overtaxed man or woman a morphine powder.

Sleep and rest ensue, but ten to one the habit is formed for life.

The happy experiences of my life in money-lending, have been two instances where I offered loans which were not asked, and which proved to be bridges over the chasm of temporary misfortune, to the success awaiting a worthy woman and man. The really deserving rarely ask for loans.

I can imagine with what pleasure you would take a cheque from this letter, for the amount which would carry you through college.

Yet when you had finished your course, you would find so many things you wanted to do, and must do, the debt would become too heavy to lift, save by borrowing from some one else.

If not that, then you would impose upon the fact of our relationship, and on your belief that I had plenty of means without the amount you owed me: and so you would join the great army of good-for-nothings in the world.

There is one thing you must always remember:

No matter how close the blood tie between two beings, even twins, each soul comes into the world alone, and with a separate life destiny to work out.

If I have worked out my destiny to financial independence, that does not entitle you to a share of it. If it seems best for me to aid you, it is not because a blood tie makes it a duty. I grow to believe there is a sort of curse on money which is not earned, even when it is bestowed by father, on son or daughter.

It cripples individual development. Only when money is earned is it blest.

Regarding your future profession, I cannot agree with your idea that because you feel no particular love for any one calling, and have a halfway tendency toward several, that you will never be a success. Great geniuses are often consumed with a passion for some one line of study or employment, but there have been many great men who did not know what they were fitted to do until accident or necessity gave them an opportunity.

Success means simply concentration and perseverance.

Whether you decide to be a mechanic, a lawyer, a doctor, or a merchant, the one thing to do is to fix all your mental powers upon the goal you select, and then call all the forces from within and from without, to aid you to reach it.

It would, of course, be folly for you to select a profession which requires special talent. No matter how you might concentrate and apply yourself, you could never be a great poet, a great artist, or a great musician.

You have not the creative genius.

But law, medicine, mechanics, or mercantile matters, with your good brain and fair education, you could conquer.

You say you vacillate from one to another, like the wind which goes to the four points of the compass in twenty-four hours.

But you are very young, and this should not discourage you.

It would be well to think the four vocations over quietly, when alone, and sit down by yourself early in the morning asking for guidance. Then, when you feel you have made a decision, let nothing turn you from it.

Direct all your studies and thoughts to further that decision.

Think of yourself as achieving the very highest success in your chosen field, and work for that end.

You cannot fail.

If you desire light from without upon the best path to pursue, I would advise you to find a good phrenologist, and have a careful reading made of your head. Its formation and the development of its organs would indicate in what direction lay your greatest strength, and where you needed to be especially watchful.

But remember if your phrenologist tells you that you have a weak will, it does not mean that you must necessarily always have a weak will. It means that you are to strengthen it, by concentration. There is a great truth underlying phrenology, palmistry, and astrology; but it is ridiculous to accept their verdicts as final and unchangeable, and it is unwise to ignore the good they may do, rightly applied and understood.

I recall the fact that you were born in early June. I know enough about the influence of the planets upon a child born at that period to assert that you are particularly inclined to a Gemini nature—the twin nature, which wants to do two things at one time. You want to stay in and go out, to read a book and play tennis, to swim and sit on the sand. Later in life, you will want to remain single and marry, and travel and remain at home, unless you begin now to select one course of the two which are for ever presenting themselves to you, in small and large matters.

Whenever you feel yourself vacillating between two impulses, take yourself at once in hand, decide upon the preferable course, and go ahead. Dominate your astrological tendencies, do not be dominated by them. Dominate your weaknesses as exhibited by your phrenological chart, and build up the brain cells which need strengthening, and lessen the power of the undesirable qualities by giving them no food or indulgence.

It is a great thing to understand yourself as you are, and then to go ahead and make yourself what you desire to be.

When a carpenter starts to build a house, he knows just what tools and what materials to work with are his. If there is a broken implement, he replaces it with another, and if he is short of material he supplies it. But young men set forth to make futures and fortunes, with no knowledge of their own equipment.

They do not know their own strongest or weakest traits, and are unprepared for the temptations and obstacles that await them.

I would advise you to call in the aid of all the occult sciences, to help you in forming an estimate of your own higher and lower tendencies, and in deciding for what line of occupation you were best fitted. Then, after you have compared the statistics so gathered with your own idea of yourself, you should proceed to make your character what you wish it to be.

This work will be ten thousand times more profitable to you than a mere routine of college studies, gained by running in debt.

To know yourself is far better knowledge than to know Virgil. And to make yourself is a million times better than to have any one else make you.

Regarding the Habit of Exaggeration

During your visit here with my niece, I became much interested in you.

Zoe had often written me of her affection for you, and I can readily understand her feeling, now that I have your personal acquaintance.

You have no mother, and your father, you say, absorbed in business, like so many American fathers, seems almost a stranger. Even the most devoted fathers, rarely understand their daughters.

Now, I want to take the part of a mother and write you to-day, as I would write my own daughter, had one been bestowed upon me with the many other blessings which are mine.

I could not ask for a fairer, more amiable, or brighter daughter than you, nor one possessed of a kinder or more unselfish nature.

You are lovable, entertaining, industrious, and refined.

But you possess one fault which needs eradicating, or at least a propensity which needs directing.

It is the habit of exaggeration in conversation.

I noticed that small happenings, amusing or exciting, became events of colossal importance when related by you.

I noticed that brief remarks were amplified and grew into something like orations when you repeated them.

I confess that you made small incidents more interesting, and insignificant words acquired poetic meaning under your tongue.

And I confess also that you never once wronged or injured any one by your exaggerations—save yourself.

Zoe often said to me, "Isn't it wonderful how Elsie's imagination lends a halo to the commonest event," and all your friends know that you have this habit of hyperbole in conversation.

Now, in your early girlhood, it is lightly regarded as "Elsie's way." Later, in your maturity, I fear it will be called a harsher name.

When you come to the time of life that larger subjects than girlish pranks and badinage engage your mind, it will be necessary for you to be more exact in your descriptions of occurrences and conversations. Besides this, there is the heritage of your unborn children to consider. I once knew a little girl who possessed the same vivid imagination, and allowed it to continue unchecked through life. She married, and her son, to-day, is utterly devoid of fine moral senses. He is a mental monstrosity—incapable of telling the truth. His falsehoods are many and varied, and his name is a synonym of untruth. He relates, as truth, the most marvellous exploits in which he really never took part, and describes scenes and places he has never visited, save through the pages of some novel.

His lack of moral sense has blighted his mother's life, and she is wholly unconscious that he is only an exaggerated edition of herself.

I think, as a rule, such imaginations as you possess belong to the literary mind. I would advise you to turn your attention to story-writing, and in that occupation you will find vent for your romantic tendencies.

Meanwhile watch yourself and control your speech.

Learn to be exact.

Tell the truth in small matters, and do not allow yourself to indulge in seemingly harmless white lies of exaggeration.

There are times when we should refrain from speaking all the truth, but we should refrain by silence or an adroit change of subject. We should not feel called upon to relate all the unpleasant truths we know of people.

When asked what we know of some acquaintance, we are justified in telling the worthy and commendable traits, and saying nothing of the faults.

Therefore, while to suppress a portion of the truth is at times wise and kind, to distort it, or misstate facts, is never needed and never excusable.

When you and Zoe came from your drive one day you were full of excitement over an adventure with a Greek road merchant.

As you told the story, the handsome peddler had accosted you at the exit of the post-office and asked you to look at his wares.