The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and

Instruction., by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction.

Volume XII, No. 347, Saturday, December 20, 1828.

Author: Various

Release Date: March 1, 2004 [EBook #11386]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MIRROR OF LITERATURE, NO. 347 ***

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Gil, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team.

| VOL. XII, NO. 347.] | SATURDAY, DECEMBER 20, 1828. | [PRICE 2d. |

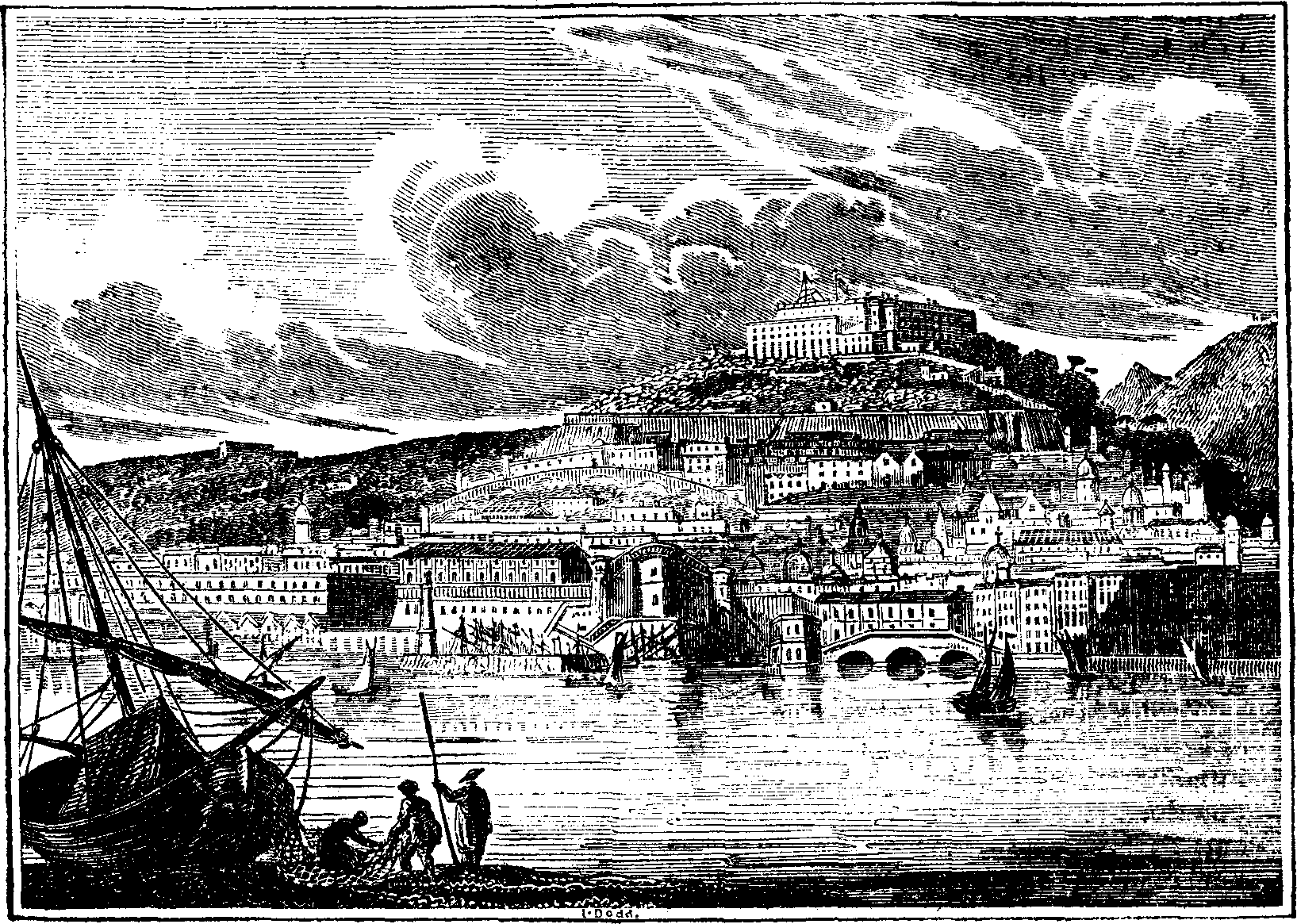

In our last volume we commenced the design of illustrating the principal Cities of Europe, by a series of picturesque views—one of which is represented in the above engraving. Our miscellaneous duties in identifying the pages of the MIRROR with subjects of contemporary interest, and anxiety to bring them on our little tapis—(qy. Twopence?)—will best account for the interval which has elapsed since the commencement of our design—with a View of London; but were all travellers as tardy, the Grand Tour of Europe would occupy many years, and leave fashion-mongers but little more than rouge, wrinkles, and bon-bons to delight their friends at home.

The proximity of Naples to Rome may, perhaps, impair the interest of the former city, especially as it presents nothing in architecture, sculpture, or painting that can vie with the Imperial Mistress. Nevertheless, Naples is one of the most beautiful and most delightful cities on the habitable globe. Nothing can possibly be imagined more unique than its coup-d'oeil, on whatever side the city is viewed.

Naples is situated towards the south and east on the declivity of a long range of hills, and encircling a gulf of 16 miles in breadth, and as many in length, which forms a basin, called Crater by the Neapolitans. The city appears to crown this superb basin. One part rises towards the west in the form of an amphitheatre, on the hills of Pausilippo, St. Ermo, and Antiguano; the other extends towards the east, over a more level territory, in which villas follow each other in rapid succession, from the Magdalen Bridge to Portici, where the king's palace is situated, and beyond that to Mount Vesuvius. The Neapolitans have a saying, Vedi Napoli e po mari, intimating that when Naples has been seen, every thing has been seen; and its congregated charms of situation, climate, and fertility almost warrant this patriotic ebullition.

"On the northern side, Naples is surrounded by hills, which (says Vasi, in his 'Picture,') form a kind of crown round the Terra di Lavoro, the Land of Labour." This consists of a district, in the language of ancient Rome,

———Lecos laeros, et amoena vireta

Fortunatorum nemorum, sedesque beatas—

and fertilized by a river, called Sebeto, which descends from the hills on the side [pg 418] of Nola, and falls into the sea after having passed under Magdalen Bridge, towards the eastern part of Naples.

The ancient history of Naples is involved in much obscurity. According to some, says Vasi, Falerna, one of the Argonauts, founded it about 1,300 years before the Christian era; according to others, Parthenope, one of the Syrens, celebrated by Homer in his "Odyssey," being shipwrecked on this coast, landed here, and built a town, to which she gave her name; others attribute its foundation to Hercules, some to Eneas, and others to Ulysses. These are mere freaks of fiction and fable; and it is more probable that Naples was founded by some Greek colonies; this may be inferred from its own name, Neapolis, and from the name of another town contiguous to it, Paleopolis. Strabo speaks of these Greek colonies, whence the city derives its origin.

The city of Naples was formerly surrounded by very high walls, about 22 miles in circumference; but on its enlargement, neither walls nor gates were erected. It may be, however, defended by three strong castles.

Naples is divided into twelve quarters, or departments, and contains about 450,000 inhabitants. It is consequently the most populous city in Europe, except London and Paris. The streets are neither broad nor regular, and are paved with broad slabs of hard stone, resembling the lava of Vesuvius. The houses are, for the most part, uniformly built, being about five or six stories high, with balconies and flat roofs, in the form of terraces, which are used as a promenade. The churches, palaces, and public buildings are magnificent; but they suffer in comparison with the other architectural wealth of Italy. Vasi states there are about 300 churches; and among the other public buildings he mentions 37 conservatories, established for the benefit of poor children, and old people, both men and women.

The environs of Naples possess many attractions for the classic tourist, as well as for the strange flies of fashion. Among these is Virgil's Tomb, which is, indeed, holy ground. The temples, aqueducts, and arches of olden time are likewise stupendous records of the sumptuousness of the ancient people of this interesting district; and, apart from these attractions, the contemplative philosopher may read in the volcanic remains, and other phenomena on its shores, many inspiring lessons in the broad volume of Nature; as well as amid the neighbouring relics of Art, where

Man marks the earth with ruin.

(For the Mirror.)

Few periods of English history are more pregnant with events, or more interesting to the antiquary, and general reader, than that which comprised the fortunes of Wolsey. The eventful life of the Cardinal, checkered as it was by the vicissitudes of fortune, his sudden elevation, and finally his more sudden fall and death, display an appalling picture of "the instability of human affairs." This prelate and statesman, who even aspired to the Papal throne itself, "was an honest poore man's sonne in the towne of Ipswiche,"1 who having received a good education, and being endowed with great capacity, soon rose to fill the highest offices of the church and state; in 1515 he was created Lord High Chancellor, and in three years afterwards was appointed legate ŗ latere by the Pope, having previously received a Cardinal's cap.

Leicester Abbey was rendered famous as being the last residence of the unhappy Wolsey; "within its walls," says Gilpin, "was once exhibited a scene more humiliating to human ambition, and more instructive to human grandeur than almost any which history hath produced. Here the fallen pride of Wolsey retreated from the insults of the world, all his visions of ambition were now gone; his pomp and pageantry and crowded levees! On this spot he told the listening monks, the sole attendants of his dying hour, as they stood around his pallet, that he was come to lay his bones among them, and gave a pathetic testimony to the truth and joys of religion, which preaches beyond a thousand lectures."2

On his road to London, whither he had been summoned, from his castle of Cawood, by Henry, to take his trial for high treason, he was seized with a disorder, which so much increased as to oblige his resting at Leicester, where he was met at the Abbey gate by the Abbot and his whole convent. The first ejaculation [pg 419] of Wolsey, on meeting these holy persons, plainly shows that he was fully aware of his approaching end: "Father Abbot," said he, "I am come hither to lay my bones among you;"3 and it was with great difficulty that they could get him up the stairs, which it was fated he was never again to descend alive. A short time previous to his death, he thus addressed the Constable of the Tower, who was appointed to convey him to the metropolis:—"Well, well, Master Kingstone, I see the matter how it is framed; but if I had serued God as diligentlie as I haue done the king, he would not haue giuen me ouer in my gray haires;4 but this is the iust reward that I must receiue for the diligent paines and study yt I haue had to doe him seruice, not regarding my seruice to God, but onely to satisfie his pleasure; I praie you haue me most humblie commended vnto his royal maiestie, and beseech him in my behalfe to call to his princelie remembrance, all matters proceeding between him and mee, from the beginning of the worlde, and the progress of the same, and most especialle in his weightie matter, and then shall his grace's conscience know whether I haue oflended him or no."5

Thus sunk into the grave a man, who was a victim to tyranny, but to a tyranny which he had himself formed; that he was a person far enlightened beyond the period in which he lived no one can presume to doubt. He tended greatly to promote the arts and learning of his country. His personal character displayed as great a variety of opposite qualities, as the fortunes to which he had been exposed; his magnanimity was oftentimes clouded by the greatest meanness, and with an urbanity of manners, he combined an intolerable degree of pride and arrogance; he was frank and generous, but his overwhelming ambition greatly tended to obscure these nobler qualities of his mind, and as he rose, he became haughty and overbearing. His character has been obscured by the envy and partiality of his contemporaries, who have generally endeavoured to load his memory with reproaches. "This Cardinall," says Holinshed, "was of great stomach, for he compted himselfe equall with princes, and by craftie suggestion got into his hands innumerable treasure; he forced little on simonie, and was not pittiful, and stood affectionate in his owne opinion; in open presence he would lie and saie vntruth, and was double both in speech and meaning; he would promise much and performe little; he was vicious of his bodie, and gaue the clergy euill example; he hated sore the Citie of London and feared it. It was told him that he should die in the waie toward London, wherefore he feared lest the commons of the citie would arise in riotous maner and so slaie him, yet for all that he died in the waie toward London, carrieng more with him out of the worlde than he brought into it, namellie, a winding sheete, besides other necessaries thought meet for a dead man, as a Christian comelinesse required."6

The remains of the Cardinal were interred in the Abbey Church at Leicester, after having been viewed by the Mayor and Corporation, (for the prevention of false rumours,) and were attended to the grave by the Abbot and all the brethren. This last ceremony was performed by torchlight, the canons singing dirges, and offering orisons, at between four and five o'clock of the morning, on St. Andrew's Day, November the 30th, 1530.

Leicester Abbey was founded (according to Leland) 7 in the year 1143, in the reign of King Stephen, by Robert Bossue, Earl of Leicester, for black canons of the order of St. Augustine, and was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It is situated in a pleasant meadow, to the north of the town, watered by the river Soar, whence it acquired the name of St. Mary de Pratis, or de la Prť. This monastery was richly endowed with lands in thirty-six of the neighbouring parishes, besides various possessions in other counties, and enjoyed considerable privileges and immunities. Bossue, with the consent of Lady Amicia, his wife, became a canon regular in his own foundation, in expiation of his rebellious conduct towards his sovereign, and particularly for the injuries which he had thereby brought upon the "goodly towne of Leycestre." At the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. the revenues of this house were valued according to Speed at £1062. 0s. 4d., Dugdale says £951. 14s. 5d.; and its site was granted in the 4th of Edward VI. to William, Marquess of Northampton.8

S.I.B.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

It will be recollected, that in a former volume I gave you the form of the oath taken by the appellee in the ancient manner of trial by battle. The appellee, when appealed of felony, pleads not guilty and throws down his glove, and declares he will defend the same by his body; the appellant takes up the glove, and replies that he is ready to make good the appeal body for body; and thereupon the appellee, taking the book in his right hand, makes oath as before mentioned. To which the appellant replies, holding the Bible and his antagonist's hand in the same manner as the other, "Hear this, O man, whom I hold by the hand, who callest thyself Thomas by the name of baptism, that thou art perjured; and therefore perjured, because that thou feloniously didst murder my father, William by name. So help me God and the Saints, and this I will prove against thee by my body, as this court shall award." And then the combat proceeds.

There is a striking resemblance between this process and that of the court of Arcopagus, at Athens, for murder, where the prisoner and prosecutor were both sworn in the most solemn manner—the prosecutor, that he was related to the deceased, (for none but near relations were permitted to prosecute in that court,) and that the prisoner was the cause of his death; the prisoner, that he was innocent of the charge against him.

In time I hope to be able to furnish you with other specimens of our curious ancient oaths.

W.H.H.

(For the Mirror.)

Whose heart is not delighted at the sound

Of rural song, of Nature's melody,

When hills and dales with harmony rebound,

While Echo spreads the pleasing strains around,

Awak'ning pure and heartfelt sympathy!

Perchance on some rude rock the minstrel stands,

While his pleased hearers wait entranced around;

Behold him touch the chords with fearless hands,

Creating heav'nly joys from earthly sound.

How many voices in the chorus rise,

And artless notes renew the failing strains;

The honest boor his vocal talent tries,

Approving love beams from his "fair one's eyes,"

While age, in silent joy, forgets its pains.

J.J.

(For the Mirror.)

The angel of death hath too surely prest

His fatal sign on the warrior's breast—

Quench'd is the light of the eagle-eye,

And the nervous limbs rest languidly—

The eloquent tongue is silent and still,

The deep clear voice again may not chill

The hearers' hearts with its own deep thrill.

Ah, who can gaze on death, nor inward feel

A creeping horror through the bosom steal,

Like one who stands upon a precipice,

And sees below a mangled sacrifice,

Feeling that he himself must ere long fall,

With none to save him, none to hear his call,

Or wrest him from the agonizing thrall?

And yet it is but sleep we look upon!

But in that sleep from which the life is gone

Sinks the proud Saladin, Egyptia's lord.

His faith's firm champion, and his Prophet's sword;

Not e'en the red cross knights withstand his pow'r,

But, sorrowing, mark the Moslem's triumph hour,

And the pale crescent float from Salem's tow'r.

As the keen arrow, hurl'd with giant-might,

Rends the thin air in its impetuous flight,

But being spent on earth innoxious lies,

E'en its track vanish'd from the yielding skies—

So lies the soldan, stopp'd his bright career,

His vanquish'd realms their prostrate heads uprear,

And coward kings forget their servile fear.

Ere yet stern Azrael10 cut the thread of life,

While Death and Nature wag'd unequal strife,

Spoke the expiring hero:—"Hither stand,

Receive your dying sovereign's last command.

When that the spirit from my frame is riven,

(Oh, gracious Alla! be my sins forgiven,

And bright-eyed Houris waft my soul to heaven,)

Then when you bear me to my last retreat,

Let not the mourners howl along the street—

Let not my soldiers in the train be seen,

Nor banners float, nor lance or sabre gleam—

Nor yet, to testify a vain regret,

O'er my remains let costly shrine be set,

Or sculptur'd stone, or gilded minaret;

But let a herald go before my bier,

Bearing on point of lance the robe I wear.

Shouting aloud, 'Behold what now remains

Of the proud conqueror of Syria's plains,

Who bow'd the Persian, made the Christian feel

The deadly sharpness of the Moslem steel;

But of his conquests, riches, honours, might,

Naught sleeps with him in death's unbroken night,

Save this poor robe.'"

D.A.H.

(For the Mirror.)

This splendid pile which is at present under repair, was erected in the time of James I. Whitehall being in a most ruinous state, he determined to rebuild it in a very princely manner, and worthy of the residence of the monarchs of the British empire. He began with pulling [pg 421] down the banquetting rooms built by Elizabeth. That which bears the above name at present was begun in 1619, from a design of Inigo Jones, in his purest style; and executed by Nicholas Stone, master mason and architect to the king; it was finished in two years, and cost £17,000. but is only a small part of a vast plan, left unexecuted by reason of the unhappy times which succeeded. The ceiling of this noble room cannot be sufficiently admired; it was painted by Rubens, who had £3,000. for his work. The subject is the Apotheosis of James I. forming nine compartments; one of the middle represents our pacific monarch on his earthly throne, turning with horror from Mars, and other of the discordant deities, and as if it were, giving himself up to the amiable goddess he always cultivated, and to her attendants, Commerce, and the Fine Arts. This fine performance is painted on canvass, and is in high preservation; but a few years ago it underwent a repair by Cipriani, who had £2,000. for his trouble. Near the entrance is a bust of the royal founder.

Little did James think (says Pennant) that he was erecting a pile from which his son was to step from the throne to the scaffold. He had been brought in the morning of his death, from St. James's across the Park, and from thence to Whitehall, where ascending the great staircase, he passed through the long gallery to his bed-chamber, the place allotted to him to pass the little time before he received the fatal blow. It is one of the lesser rooms marked with the letter A in the old plan of Whitehall. He was from thence conducted along the galleries and the banquetting house, through the wall, in which a passage was broken to his last earthly stage. Mr. Walpole tells us that Inigo Jones, surveyor of the works done about the king's house, had only 8s. 4d. a day, and £46. a year for house-rent, and a clerk and other incidental expenses. The present improvements at Whitehall make one exclaim with the poet, Pope—

"I see, I see, where two fair cities bend

Their ample brow, a new Whitehall ascend."

Again,

"You too proceed, make falling arts your care,

Erect new wonders, and the old repair;

Jones and Palladio to themselves restore,

And be whate'er Vitruvius was before."

(For the Mirror.)

O light celestial, streaming wide

Through morning'd court of fairy blue—

O tints of beauty, beams of pride,

That break around its varied hue—

Still to thy wonted pathway true,

Thou shinest on serenely free,

Best born of Him, whose mercy grew

In every gift, sweet world, to thee.

O countless stars, that, lost in light,

Still gem the proud sun's glory bed,

And o'er the saddening brow of night

A softer, holier influence shed—

How well your radiant march hath sped.

Unfailing vestals of the sky,

As smiling thus ye weed from dread

The soul ye court to muse on high.

O flowers that breathe of beauty's reign,

In many a tint o'er lawn and lea,

That give the cold heart once again

A dream of happier infancy;

And even on the grave can be

A spell to weed affection's pain—

Children of Eden, who could see.

Nor own His bounty in your reign?

O winds, that seem to waft from far

A mystic murmur o'er the soul,

As ye had power to pass the bar

Of nature in your vast control,

Hail to your everlasting roll—

Obedient still ye wander dim,

And softly breathe, or loudly toll,

Through earth and sky the name of Him.

O world of waters, o'er whose bed

The chainless winds unceasing swell,

That claim'st a kindred over head,

As 'twixt the skies thou seem'st to dwell;

And e'en on earth art but a spell,

Amid their realms to wander free—

Thy task of pride hath speeded well,

Thou deep, eternal, boundless sea.

O storms of night and darkness, flung

In blackening chaos o'er the world,

When thunderpeals are dreadly rung,

Mid clouds in sightless fury hurl'd,

Types of a mightier power, impearl'd

With mercy's soft, redeeming ray,

Still at His voice your wings are furl'd,

Ye wake to own and to obey.

O thou blest whole of light and love,

Thou glorious realm of earth and sky,

That breath'st of blissful hope above,

When all of thine hath wander'd by,

Throughout thy range, nor tear nor sigh

But breathes of bliss, of beauty's reign,

And concord, such as in the sky

The soul is taught to meet again.

O man, who veil'd in deepest night

This beauty-breathing world of thine,

And taught the serpent's deadly blight

Amid its sweetest flowers to twine,

Thou, thou alone hast dared repine,

And turn'd aside from duty's call,

Thou who hast broken nature's shrine,

And wilder'd hope and darken'd all.

ANNETTE TURNER.

A half-pint of wine for young men in perfect health is enough, and you will be able to take your exercise better, and feel better for this abstinence.—Dr. Babington.

We had gone into Devonshire, for the purpose of being more retired, that we might study more attentively, and with less chance of interruption, than in a town. We chose, accordingly, for our residence, one of the most beautiful and retired cottages we ever saw. It was situated very near the sea; and, oh! what thoughts used to steal over us, of romance and true love, as we gazed upon that quiet ocean, from the vine-covered window of our quiet, sweet, secluded home! Day after day, we wandered among the woods in the neighbourhood, and rejoiced, at each successive visit, to find out new beauties. This continued for some time; till at last, on returning one day, we saw an unusual bustle in the room we occupied. On entering, we found our landlady hurrying out in great confusion, and, along with her, a beautiful, blushing girl, so perfectly ladylike in her appearance, that we wondered by what means our venerable hostess could have become acquainted with so interesting a visiter. She soon explained the mystery; this lady, who seemed more bewitching every moment that we gazed on her, was the daughter of a 'squire in whose family our worthy landlady had been nurse. She had come, without knowing that any lodger was in the house, and was to stay a week. Oh! that week! the happiest of our life. We soon became intimate; our books lay fast locked up at the bottom of our trunk: we walked together, saw the sun set together in the calm ocean, and then walked happily and contentedly home in the twilight; and long before the week was at an end, we had vowed eternal vows, and sworn everlasting constancy. We had not, to be sure, discovered any great powers of mind in our enslaver; but how interesting is even ignorance, when it comes from such a beautiful and smiling mouth! We had already formed happy plans of moulding her unformed opinions, and directing and sharing all her studies. The little slips which were observable in her grammar, we attributed to want of care; and the accent, which was very powerful, was rendered musical to our ear, at the same time as dear to our heart, by the whiteness of the little arm that lay so quietly and lovingly within our own. And then, her taste in poetry was not the most delicate or refined; but she was so enthusiastically fond of it, that we imagined a little training would lead her to prefer many of Mr. Moore's ballads, to the pathos of Giles Scroggins; and that in time, the "Shining River" might occupy a superior place, in her estimation, to a song from which she repeated, with tears in her eyes—,

"But like the star what lighted

Pale billion to its fated doom,

Our nuptial song is blighted,

And its rose quench'd in its bloom."

And then, she seemed so fond of flowers, and knew so much about their treatment, that we fancied how lovely she must look while engaged in that fascinating study; and often, in our dreaming moods, did we mutter about

"Fair Proserpine

Within the vale of Enna gathering flowers,

Herself the fairest flower."—

But why should we repeat what every one can imagine so well for himself? At last, the hour of parting came; and, week after week, her stay at the cottage had been prolonged, till our departure took place before hers. And on that day she looked, as all men's sweethearts do at leaving them, more touchingly beautiful than ever we had seen her before; and after we had torn ourself away, we looked back, and there we saw her standing in the same spot we had left her, a statue of misery and despair,—"like Niobe all tears."

Astonishment occupied the minds of all our friends on our return to college. The change which took place on our feelings and conduct was indeed amazing; our mornings were devoted to gazing on a lock of our—she was rather unfortunate in a name—our Grizel's hair, and to lonely hours of musing in the meadow on all the adventures of our sojourn in Devonshire. No longer we stood listlessly in the quadrangle, joining the knots of idlers, of whom we used to be one of the chief; no longer had even Castles' Havannahs any charms for our lips; and our whole heart was wrapt up in the expectation of a letter. This we were not to receive for three long weeks; and by that time she was to have returned home, consulted her father on the subject of our attachment, and return us a definitive reply. We wrote in the meantime—such a letter! We are assured it must have been written on a sheet of asbestos, or it must infallibly have taken fire. It began, "Lovely and most beautiful Grizel!" and ended, "Your adorer." At last the letter that was to conclude all our hopes was put into our hands. We had some men that morning to breakfast; we received it just as they were beginning the third pie. How heartily we prayed they would he off and leave us alone! But no—on they kept swallowing pigeon [pg 423] after pigeon, and seemed to consider themselves as completely fixtures as the grate or the chimney-piece. We wished devoutly to see a bone sticking in the throat of our most intimate friend, and, by way of getting quit of them, had thoughts of setting fire to the room. At last, however, they departed. Immediately as the skirt of the last one's coat disappeared, we carefully locked and bolted our door, and, with hands trembling with joy, we took out the letter. Not very clean was its appearance, and not over correct or well-spelt was its address; and, above all, a yellow, dingy wafer filled up the place of the green wax we had expected, and the true lover's motto, "Though lost to sight, to memory dear," was supplied by the impression of a thimble. We opened it. Horror and amazement! never was such penmanship beheld. The lines were complete exemplifications of the line of beauty, so far as their waving, and twisting, and twining was concerned; and the orthography it was past all human comprehension to understand.

"My deerest deere, dear sur,"—this was the letter,—"i kim him more nor a wic agon, butt i cuddunt right yu afore ass i av bin with muther an asnt seed father till 2 day. he sais as my fortin is 3 hundurd pouns, he sais as he recomminds me tu take mi hold lover Mister Tomas the gaurdnar, he sais as yu caunt mary no boddi, accause you must be a batseller three ears. if thiss be troo i am candied enuff to tell you ass i caunt wate so long my deerast deer, o yu ave brock mi art! wy did yu sai al ass yu sad iff yu cud unt mary nor none of the scolards at hocksfoot Kolidge. father sais as ther iss sum misstake praps yu did unt no ass mother is not marid 2 father butt is marrid to the catchmun and father is marad to a veri gud ladi ass gove me a gud edocasion. mi deerest deere it brakes my art all from yu for tu part, i rot them lines this marnin. mister tomas sais as i gov im mi prumass befor i cum to ave the apiness of see yu. butt i dant thinc i giv mor promass to him. nor 2 manni uthers. mi deerest deer and troo luv cuppid! i feer our nutshell song is blitid and its ros kwencht in its blum. them was plesent ours when the carnashuns and tullups was all in blo, wasunt them mi deer luv. mister tomas sais ass he can mari me in a munth and father sais i hot tu take im. iff so be as yu caun't du it beefor i thinc i shal take im ass father sais there is sum mistake, mi deerest deere mi art is brock butt i thinc i shall take im iff so bee as I dant ear frum yu. gud nite my troo luv i shal kip your lockat for a kipsic an yu ma kiss my luck off air for the sack of your brockan arted

"GRIZEL."

It is astonishing how the perusal of this cured us of our affection. At the first line we recollected that she had a tendency to squint, and long before we came to the conclusion, we remembered that her ancles were rather thick, and her feet by no means of diminutive size. Thus ended our love adventures at the University. Our heroine we have never heard of since, and we have resisted the most tempting offers from the loveliest of her sex; and in spite of sighing heiresses and compassionate old maids, we are still a bachelor; and a bachelor, in defiance of all their machinations, we are firmly determined to remain.—Blackwood's Magazine.

(For the Mirror.)

Many singular customs are observed in the Netherlands at Christmas, and as they materially differ from those known in England, a brief notice of one of them may probably prove acceptable to the readers of the MIRROR.

In almost every Dutch town, and in every considerable village, the following custom prevails:—At a little after two o'clock in the morning of Christmas-day, a number of young men assemble in the market-place, and sing some verses suited to the occasion. One of the young men bears an artificial star, which is fixed to a pole, and elevated above the heads of the people; it is very large, and is rendered beautifully transparent when a light is placed in the inside. This artificial luminary is intended to represent the star of the east, which directed the wise men to Bethlehem, the birthplace of Christ. At a little distance, the appearance is exceedingly brilliant, for there is no other light among the populace to diminish its lustre, and the whole scene is singularly picturesque. The resplendent light issuing from the star strikes powerfully upon the countenances of the principal actors, while those more remote receive only a faint and subdued gleam. The silvery effulgence of the moon, the sombre and deserted look of the buildings around, and the general stillness that pervades every object, save the scene of action, might inspire the mind of a Rembrandt, or introduce to the mere casual beholder feelings at once new and poetical.

After parading through the town, the youths repair in a body to the residence [pg 424] of some opulent inhabitant, where their arrival is welcomed with shouts and clapping of hands, and where they are entertained with a plentiful repast.

G.W.N.

Their present actual numbers may, perhaps, not exceed six millions—numbers, however, probably greater than those over which Solomon reigned; and of these six millions there may be resident in the contiguous countries of Moravia, Ancient Poland, the Crimea, Moldavia, and Wallachia, above three millions. Except within the countries which formed Poland before its partitions, their population contained in any one European kingdom, cannot, therefore, be great. Yet so essentially are they one people, we might almost say one family; and so disposable is their wealth, as mainly vested in money transactions, that they must be considered as an aggregate, and not in their individual portions.

The Jews in France are perhaps from thirty to forty thousand; they abound chiefly at Metz, along the Rhine, and at Marseilles and Bordeaux. In Bonaparte's time they were imagined to amount to at least twice that number.—They are relieved from civil restraints and disabilities in France, and in the Netherlands also. The Jews in Holland, of both German and Portuguese origin, are numerous; the latter are said to have taken refuge there when the United Provinces asserted their independence of Spain; they have a splendid synagogue at Amsterdam. Infidelity is supposed to have made more progress amongst them than amongst the German Jews in Holland. The Italian Jews are chiefly at Leghorn and Genoa; and there are four thousand of them at Rome. In speaking of the religion of the Jews, it is not necessary to particularize those who assumed the mask of Christianity under terror of the Inquisition, although much has been said of their wealth and numbers, and of the high offices they have filled in Spain, and especially in Portugal. But it is curious to see, in a very distant quarter, a like simulation produced amongst them by like causes. There are at Salonica thirty synagogues, and about twenty-five thousand professed Jews; and a body of Israelites have been lately discovered there, who, really adhering to the faith of their fathers, have externally embraced Mahomedanism.

The Barbary Jews are a very fine people; but the handsomest Jews are said to be those of Mesopotamia. That province may also boast of an Arab chief who bears the name of the Patriarch Job, is rich in sheep, and camels, and oxen, and asses, abounds in hospitality, and believes that he descends from him; he is also famed for his justice. The Jews at Constantinople, forty thousand in number, and in the parts of European Turkey on and near the Mediterranean, speak Spanish, and appear to descend from Israelites driven from Spain by persecution. The Bible Society are now printing at Corfu the New Testament, in Jewish-Spanish, for their benefit.

In truth, little appears to be known of the state of the Jews during some hundreds of years after the destruction of Jerusalem. The first body of learned Jews which drew attention after that disastrous event was that settled in Spain; and from it all Jewish learning descends. As in accomplishment of the prophecy, the Jew is found over the whole surface of the globe; he has been long established in China, which abhors the foreigner; and in Abyssinia, which it is almost as difficult to reach as to quit. The early Judaism of that country, and in later days the history of the powerful colony of Jews established in its heart, which at one time actually reigned over the kingdom, are matters so curious, that we regret that we can do no more than advert to them; we must say the same as to the evidence existing of Jewish rites having extended themselves very far southward along the eastern coast of Africa; the numerous Jews of Barbary; and the black and white Jews, who have been established for ages, more or less remote, on the Malabar coast. It may be here observed, that all the Israelites hitherto discovered appear to be descendants of those who held the kingdom of Judah.

The Jews in Great Britain and Ireland are not supposed to be more than from ten to twelve thousand, very many of whom are foreigners, and migratory.—Quarterly Rev.

The rations of the Egyptian soldiers were, according to Herodotus, five pounds of baked bread, two pounds of beef, and half a pint of wine daily.

In the barbarous ages it was usual for persons who could not write, to make the sign of the cross in confirmation of a written paper. Several charters still remain in which kings and persons of great eminence affix "signum crucis pro ignoratione literarum," the sign of the cross, because of their ignorance of letters. From this is derived the phrase of signing instead of subscribing a paper.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

You have lately directed the attention of the readers of the MIRROR to the park of Blenheim, in Oxfordshire, one of the most beautiful England can boast of, and likewise, according to Camden, the first park that was made in this country. I can bear witness to the correctness of your delineation and description of Rosamond's Well, which you gave in a recent number; but there is no trace whatever of the bower or labyrinth, the site of which is only pointed out by tradition. The park of Blenheim, besides the interest which attaches to it from the circumstance of its having been the residence of the early kings of England, and the scene of "Rosamond's" life, has in more modern times acquired additional interest from having been bestowed by the country upon the Duke of Marlborough, in testimony of the gratitude of the nation for the brilliant services he had rendered his country, particularly at the battle of Blenheim.

It was a reward at once worthy of the English nation and of the illustrious hero on whom it was bestowed; and as it is at least pleasing, and perhaps useful, to recall to the mind the epochs of England's greatness amongst nations, I have sent a sketch of one of the most prominent objects in the park of Blenheim, which our forefathers deemed (in the language of the inscription) would "stand as long as the British name and language last, illustrious monuments of Marlborough's glory and of Britain's gratitude." This is an elegant column, 130 feet in height, and surmounted by a statue of the warrior in an antique habit. On three sides of the building there are nearly complete copies of the several Acts of Parliament by which the park and manor of Woodstock were granted to the Duke of Marlborough and his heirs; and on the fourth side is a very long inscription, said to have been penned by Lord Bolingbroke, which concludes thus:—

These are the actions of the Duke of Marlborough,

Performed in the compass of a few years,

Sufficient to adorn the annals of ages.

The admiration of other nations

Will be conveyed to the latest posterity,

In the histories even of the enemies of Britain.

The sense which the British nation had

Of his transcendant merit

Was expressed

In the most solemn, most effectual, most durable manner.

The Acts of Parliament inscribed on the pillar

Shall stand as long as the British name and language last,

Illustrious monuments

Of Marlborough's glory and

Of Britain's gratitude.

G.W.

This is as full-charged a portrait of human depravity as the gloomiest misanthrope could wish for. But it has much wider claims on public attention than the gratification of the misanthropic few who mope in corners or stalk up and down leafless and almost solitary walks during this hanging and drowning season. Nevertheless, all men are more or less misanthropes, or they affect to be so; for only skim off the bile of a true critic, or the minds of the hundred thousand who read newspapers, and look first for the bankrupts and deaths. Sugar and wormwood and wormwood and sugar are the standing dishes, but as we read the other day, "there is a certain hankering for the gloomy side of nature, whence the trials and convictions of vice become so much more attractive than the brightest successes [pg 426] of virtue." People with macadamized minds, and their histories (scarce as the originals are) are mere nonentities, and food for the trunk-maker; whereas a book of hair-breadth escapes, thrilling with horror and romantic narrative will tempt people to sit up reading in their beds, till like Rousseau, they are reminded of morning by the stone-chatters at their window. To the last class belong the Memoirs of Vidocq, an analysis of which would be "utterly impossible, so powerful are the descriptions, and so continuous the thread of their history." The original work was published a short time since in Paris, and republished here; but, we believe the present is the first translation that has appeared in England. The newspapers have, from time to time, translated a few extracts, when their Old Bailey news was at a stand, so that the name of Vidocq must be somewhat familiar to many of our readers.11

Eugene Francois Vidocq is a native of Arras, where his father was a baker; and from early associations he fell into courses of excess which led to the necessity of his flying from the parental roof. After various, rapid, and unexampled events in the romance of real life, in which he was everything by turns and nothing long, he was liberated from prison, and became the principal and most active agent of police. He was made Chief of the Police de Surete under Messrs. Delavau and Franchet, and continued in that capacity from the year 1810 till 1827, during which period he extirpated the most formidable of those ruffians and villains to whom the excesses of the revolution and subsequent events had given full scope for the perpetration of the most daring robberies and inquitous excesses. Removed from employment, in which he had accumulated a handsome independence, he could not determine on leading a life of ease, for which his career of perpetual vigilance and adventure had unfitted him, and he built a paper manufactory at St. Mandeť, about two leagues from Paris, where he employs from forty to fifty persons, principally, it is asserted, liberated convicts, who having passed through the term of their sentence, are cast upon society without home, shelter, or character, and would be compelled to resort to dishonest practices did not this asylum offer them its protection and afford them opportunity of earning an honest living by industrious labour. One additional point of interest in the present volume is, that the author is still living.

[We cannot follow Vidocq through his career of crime, neither would it be altogether profitable to our readers; but the links may be recapitulated in a few words. He must have been born a thief, and perhaps stole the spoon with which he was fed; but the penchant runs in the family, for Vidocq and his brother rob the same till of a fencing-room, but his brother is first detected, and sent off "in a hurry," to a baker at Lille. Of course Vidocq soon gets partners in sin, and on the same day that he has been detected by the living evidence of two fowls which he had stolen, he sweeps from the dinner table ten forks and as many spoons, pawns them for 150 francs, spends the money in a few hours, and is imprisoned four days. He is then released; one of his pals gives a false alarm to Vidocq's mother, and during her temporary absence, Vidocq enters his home with a false key, steals 2,000 francs from a strong chest, with which he escapes to Ostend, (intending to embark for America,) where he is decoyed by a soi-disant ship-broker, and loses all his ill-gotten wealth. He then resolves to betroth the sea, though not after the Venetian fashion, by giving her a dowry; the "sound of a trumpet" disturbs his attention, as it would of any other hero. But this proves to be the note of Paillasse, a merry-andrew. The "director," as the opera bills would say, was Cotte-Comus, belonging to a troop of rope-dancers.

He next joins a player of Punch, to whose wife he enacts Romeo with better grace, and during one of the representations, the married people break each others heads, and Vidocq runs off during the affray. He then becomes assistant to a quack doctor, and the favoured swain of an actress; gets into the Bourbon regiment, where he is nicknamed Reckless, and kills two men, and fights fifteen duels in six months. His other exploits are as a corporal of grenadiers, of course, a deserter, and a prisoner of the revolution. He then marries, but does not reform. Of course a wife is but a temporary incumbrance to a man of Vidocq's dexterity. In chapter iii, we find him at Brussels, where he joins a set of nefarious gamblers at the Cafes, and has a most romantic adventure with a woman named Rosine. But we can follow him no further, except to add that his other comrades in Vol. I, are gipsies, smugglers, players, [pg 427] galley-slaves, drovers, Dutch sailors, and highwaymen.

We must, therefore, confine ourselves to a few detached extracts from the most interesting portion of the volume. At Lille, Vidocq meets with a chere amie, Francine; he suspects her fidelity, thrashes his rival, gets imprisoned, and is betrayed as an accomplice in a forgery. His "reflections" during his imprisonment in St. Peter's Tower, bring on a severe illness.]

I was scarcely convalescent, when, unable to support the state of incertitude in which I found my affairs, I resolved on escaping, and to escape by the door, although that may appear a difficult step. Some particular observations made me choose this method in preference to any other. The wicket-keeper at St. Peter's Tower was a galley-slave from the Bagne (place of confinement) at Brest, sentenced for life. In a word, I relied on passing by him under the disguise of a superior officer, charged with visiting St. Peter's Tower, which was used as a military prison, twice a week.

Francine, whom I saw daily, got me the requisite clothing, which she brought me in her muff. I immediately tried them on, and they suited me exactly. Some of the prisoners who saw me thus attired assured me that it was impossible to detect me. I was the same height as the officer whose character I was about to assume, and I made myself appear twenty-five years of age. At the end of a few days, he made his usual round, and whilst one of my friends occupied his attention, under pretext of examining his food, I disguised myself hastily, and presented myself at the door, which the gaolkeeper, taking off his cap, opened, and I went out into the street. I ran to a friend of Francine's, as agreed on in case I should succeed, and she soon joined me there.

I was there perfectly safe, if I could resolve on keeping concealed; but how could I submit to a slavery almost as severe as that of St. Peter's Tower. As for three months I had been enclosed within four walls, I was now desirous to exercise the activity so long repressed. I announced my intention of going out; and, as with me an inflexible determination was always the auxiliary of the most capricious fancy, I did go. My first excursion was safely performed, but the next morning, as I was crossing the Rue Ecremoise, a sergeant named Louis, who had seen me during my imprisonment, met me, and asked if I was free. He was a severe practical man, and by a motion of his hand could summon twenty persons. I said that I would follow him; and begging him to allow me to bid adieu to my mistress, who was in a house of Rue de l'HŰpital, he consented, and we really met Francine, who was much surprised to see me in such company; and when I told her that having reflected, that my escape might injure me in the estimation of my judges, I had decided on returning to St. Peter's Tower, to wait the result of the process.

Francine did not at first comprehend why I had expended three hundred francs, to return at the end of four months to prison. A sign put her on her guard, and I found an opportunity of desiring her to put some cinders in my pocket whilst Louis and I took a glass of rum, and then set out for the prison. Having reached a deserted street, I blinded my guide with a handful of cinders, and regained my asylum with all speed.

Louis having made his declaration, the gendarmes and police-officers were on the full cry after me; and there was one Jacquard amongst them who undertook to secure me if I were in the city. I was not unacquainted with these particulars, and instead of being more circumspect in my behaviour, I affected a ridiculous bravado. It might have been said that I ought to have had a portion of the premium promised for my apprehension. I was certainly hotly pursued, as may be judged from the following incident:—

Jacquard learnt one day that I was going to dine in Rue Notre-Dame. He immediately went with four assistants, whom he left on the ground-floor, and ascended the staircase to the room where I was about to sit down to table with two females. A recruiting sergeant, who was to have made the fourth, had not yet arrived. I recognised Jacquard, who never having seen me, had not the same advantage, and besides my disguise would have bid defiance to any description of my person. Without being at all uneasy, I approached, and with a most natural tone I begged him to pass into a closet, the glass door of which looked on the banquetroom. "It is Vidocq whom you are looking for," said I; "if you will wait for ten minutes you will see him. There is his cover, he cannot be long. When he enters, I will make you a sign; but if you are alone, I doubt if you can seize him, as he is armed, and resolved to defend himself."—"I have my gendarmes on the staircase," answered he, "and if he escapes—"—"Take care how you place them then," said I with affected haste. "If Vidocq should see them he would mistrust some plot, and then farewell to the bird."—"But where shall I place them?"—"Oh, why in this closet—mind, [pg 428] no noise, that would spoil all; and I have more desire than yourself that he should not suspect anything." My commissary was now shut up in four walls with his agents. The door, which was very strong, closed with a double lock. Then, certain of time for escape, I cried to my prisoners, "You are looking for Vidocq—well, it is he who has caged you; farewell." And away I went like a dart, leaving the party shouting for help, and making desperate efforts to escape from the unlucky closet.

Two escapes of the same sort I effected, but at last I was arrested and carried back to St. Peter's Tower, where, for greater security, I was placed in a dungeon with a man named Calendrin, who was also thus punished for two attempts at escape. Calendrin, who had known me during my first confinement in the prison, imparted to me a fresh plan of escape, which he had devised by means of a hole worked in the wall of the dungeon of the galley-slaves, with whom we could communicate. The third night of my detention all was managed for our escape, and eight of the prisoners who first went out were so fortunate as to avoid being detected by the sentinel, who was only a short distance off.

Seven of us still remained, and we drew straws, as is usual in such circumstances, to determine which of the seven should first pass. I drew the short straw, and undressed myself that I might get with greater ease through the hole, which was very narrow, but to the great disappointment of all, I stuck fast without the possibility of advancing or receding. In vain did my companions endeavour to pull me out by force, I was caught as if in a trap, and the pain of my situation was so extreme, that not expecting further help from within, I called to the sentry to render me assistance. He approached with the precaution of a man who fears a surprise, and presenting his bayonet to my breast, forbade me to make the slightest movement. At his summons the guard came out, the porters ran with torches, and I was dragged from my hole, not without leaving behind me a portion of my skin and flesh. Torn and wounded as I was, they immediately transferred me to the prison of Petit Hotel, when I was put into a dungeon, fettered hand and foot.

Ten days afterwards I was placed amongst the prisoners, through my intreaties and promises not to attempt again to escape.

[Here he meets with a fellow named Bruxellois, the Daring, of whom the following anecdote is related:—]

At the moment of entering a farm with six of his comrades, he thrust his left hand through an opening in the shutter to lift the latch, but when he was drawing it back, he found that his wrist had been caught in a slip knot. Awakened by the noise, the inhabitants of the farm had laid this snare, although too weak to go out against a band of robbers which report had magnified as to numbers. But the attempt being thus defeated, day was fast approaching, and Bruxellois saw his dismayed comrades looking at each other with doubt, when the idea occurred to him that to avoid discovery they would knock out his brains. With his right hand he drew out his clasp knife with a sharp point, which he always had about him, and cutting off his wrist at the joint, fled with his comrades without being stopped by the excessive pain of his horrid wound. This remarkable deed, which has been attributed to a thousand different spots, really occurred in the vicinity of Lille, and is well authenticated in the northern districts, where many persons yet remember to have seen the hero of this tale, who was thence called Manchot, (or one-armed,) executed.

[Vidocq at length escapes, quits Lille, and flies to Ostend, where he joins a crew of smugglers.]

It was with real repugnance that I went to the house of a man named Peters, to whom I was directed, as one deeply engaged in the pursuit, and able to introduce me to it. A sea-gull nailed on his door with extended wings, like the owls and weasels that we see on barns, guided me. I found the worthy in a sort of cellar, which by the ropes, sails, oars, hammocks, and barrels which filled it, might have been taken for a naval depot. From the midst of a thick atmosphere of smoke which surrounded him, he viewed me at first with a contempt which had not a good appearance, and my conjectures were soon realized, for I had scarcely offered my services than he fell upon me with a shower of blows. I could certainly have resisted him effectually, but astonishment had in a measure deprived me of the power of defence; and I saw besides, in the court-yard, half-a-dozen sailors and an enormous Newfoundland dog, which would have been powerful odds. Turned into the street, I endeavoured to account for this singular reception, when it occurred to me that Peters had mistaken me for a spy, and treated me accordingly.

This idea determined me on returning to a dealer in hollands, who had told me of him, and he, laughing at the results of my visit, gave me a pass-word that would procure me free access to Peters.—[He [pg 429] succeeds.]—I slept at Peters's house with a dozen or fifteen smugglers, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Portuguese, and Russian; there were no Englishmen, and only two Frenchmen. The day after my installation, as we were all getting into our hammocks, or flock beds, Peters entered suddenly into our chamber, which was only a cellar contiguous to his own, and so filled with barrels and kegs, that we could scarcely find room to sling our hammocks. Peters had put off his usual attire, which was that of ship-caulker, or sail-maker, and had on a hairy cap, and a long red shirt, closed at the breast with a silver pin, fire-arms in his belt, and a pair of thick large, fisherman's boots, which reach the top of the thigh, or may be folded down beneath the knee.

"A-hoy! a-hoy!" cried he, at the door, striking the ground with the butt end of his carbine! "down with the hammocks, down with the hammocks! We will sleep some other day. The Squirrel has made signals for a landing this evening, and we must see what she has in her, muslin or tobacco. Come, come, turn out, my sea-boys."

In a twinkling every body was ready. They opened an arm-chest, and every man took out a carbine or blunderbuss, a brace of pistols, and a cutlass or boarding pike, and we set out, after having drunk so many glasses of brandy and arrack that the bottles were empty. At this time there were not more than twenty of us, but we were joined or met, at one place or another, by so many individuals, that on reaching the sea side we were forty-seven in number, exclusive of two females and some countrymen from the adjacent villages, who brought hired horses, which they concealed in a hollow behind some rocks.

It was night, and the wind was shifting, whilst the sea dashed with so much force, that I did not understand how any vessels could approach without being cast on shore. What confirmed this idea was, that by the starlight I saw a small boat rowing backwards and forwards, as if it feared to land. They told me afterwards that this was only a manoeuvre to ascertain if all was ready for the unloading, and no danger to be apprehended. Peters now lighted a reflecting lantern, which one of the men had brought, and immediately extinguished it; the Squirrel raised a lantern at her mizen, which only shone for a moment, and then disappeared like a glow-worm on a summer's night. We then saw it approach, and anchor about a gun-shot off from the spot where we were. Our troop then divided into three companies, two of which were placed five hundred paces in front, to resist the revenue officers if they should present themselves. The men of these companies were then placed at intervals along the ground, having at the left arm a packthread which ran from one to the other: in case of alarm, it was announced by a slight pull, and each being ordered to answer this signal by firing his gun, a line of firing was thus kept up, which perplexed the revenue officers. The third company, of which I was one, remained by the sea-side, to cover the landing and the transport of the cargo.

All being thus arranged, the Newfoundland dog already mentioned, and who was with us, dashed at a word into the midst of the waves, and swam powerfully in the direction of the Squirrel, and in an instant afterwards returned with the end of a rope in his mouth. Peters instantly seized it, and began to draw it towards him, making us signs to assist him, which I obeyed mechanically. After a few tugs, I saw that at the end of the cable were a dozen small casks, which floated towards us. I then perceived that the vessel thus contrived to keep sufficiently far from the shore, not to run a risk of being stranded. In an instant the casks, smeared over with something that made them waterproof, were unfastened and placed on horses, which immediately dashed off for the interior of the country. A second cargo arrived with the same success; but as we were landing the third, some reports of fire-arms announced that our outposts were attacked. "There is the beginning of the ball," said Peters, calmly; "I must go and see who will dance;" and taking up his carbine, he joined the outposts, which had by this time joined each other. The firing became rapid, and we had two men killed, and others slightly wounded. At the fire of the revenue officers, we soon found that they exceeded us in number; but alarmed, and fearing an ambuscade, they dared not to approach, and we effected our retreat without any attempt on their part to prevent it. From the beginning of the fight the Squirrel had weighed anchor and stood out to sea, for fear that the noise of the firing should bring down on her the government cruiser. I was told that most probably she would unload her cargo in some other part of the coast, where the owners had numerous agents.

[Vidocq returns to Lille, where he is taken by two gendarmes, and concerts the following stratagem for escape:—]

This escape, however, was not so very easy a matter as may be surmised, when I say that our dungeons, seven feet square, had walls six feet thick, strengthened [pg 430] with planking crossed and rivetted with iron; a window, two feet by one, closed with three iron gratings placed one after the other, and the door cased with wrought iron. With such precautions, a jailor might depend on the safe keeping of his charge, but yet we overcame it all.

I was in a cell on the second floor with Duhamel. For six francs, a prisoner, who was also a turnkey, procured us two files, a ripping chisel, and two turnscrews. We had pewter spoons, and our jailor was probably ignorant of the use which prisoners could make of them. I knew the dungeon key; it was the counterpart of all the others on the same story; and I cut a model of it from a large carrot; then I made a mould with crumb of bread and potatoes. We wanted fire, and we procured it by making a lamp with a piece of fat and the rags of a cotton cap. The key was at last made of pewter, but it was not yet perfect; and it was only after many trials and various alterations that it fitted at last. Thus masters of the doors, we were compelled to work a hole in the wall, near the barns of the town-hall. Sallambier, who was in the dungeons below, found a way to cut the hole, by working through the planking.

The prison of BicÍtre is a neat quadrangular building, enclosing many other structures and many courts, which have each a different name; there is the grande cour (great court) where the prisoners walk; the cour de cuisine (or kitchen court;) the cour des chiens (or dog's court;) the cour de correction (or court of punishment;) and the cour des fers (or iron court.) In this last is a new building five stories high; each story contains forty cells, capable of holding four prisoners. On the platform, which supplies the place of a roof, was night and day a dog named Dragon, who passed in the prison for the most watchful and incorruptible of his kind; but some prisoners managed at a subsequent period to corrupt him through the medium of a roasted leg of mutton, which he had the culpable weakness to accept. The Amphytrions escaped whilst Dragon was swallowing the mutton; he was beaten and taken into the cour des chiens, where, chained up and deprived of the free air which he breathed on the platform, he was inconsolable for his fault, and perished piecemeal, a victim of remorse at his weakness in yielding to a moment of gluttony and error.

Near the erection I speak of is the old building, nearly arranged in the same way, and under which were dungeons of safety, in which were enclosed the troublesome and condemned prisoners. It was in one of these dungeons that for forty-three years lived the accomplice of Cartouche, who betrayed him to procure this commutation! To obtain a moment's sunshine, he frequently counterfeited death so well, that when he had actually breathed his last sigh, two days passed before they took off his iron collar. A third part of the building, called La Force, comprised various rooms, in which the prisoners were placed who arrived from the provinces, and were destined to the chain.

At this period, the prison of BicÍtre, which is only strong from the strict guard kept up there, could contain twelve hundred prisoners; but they were piled on each other, and the conduct of the jailors in no way assuaged the inconvenience of the place.

If any man arrived from the country well clad, who, condemned for a first offence, was not as yet initiated into the customs and usages of prisons, in a twinkling he was stripped of his clothes, which were sold in his presence to the highest bidder. If he had jewels or money, they were alike confiscated to the profit of the society, and if he were too long in taking out his ear-rings, they snatched them out without the sufferer daring to complain. He was previously warned, that if he spoke of it, they would hang him in the night to the bars of his cell, and afterwards say that he had committed suicide. If a prisoner, out of precaution, when going to sleep, placed his clothes under his head, they waited until he was in his first sleep, and then they tied to his foot a stone, which they balanced at the side of his bed; at the least motion the stone fell, and aroused by the noise, the sleeper jumped up, and before he could discover what had occurred, his packet hoisted by a cord, went through the iron bars to the floor above. I have seen, in the depth of winter, these poor devils, having been deprived of their property in this way, remain in the court in their shirts until some one threw them some rags to cover their nakedness. As long as they remained at BicÍtre, by burying themselves, as we may say, in their straw, they could defy the rigour of the weather; but at the departure of the chain, when they had no other covering than the frock and trousers made of packing cloth, they often sunk exhausted and frozen before they reached the first resting place.

[As we have said, the present is but a fourth portion of Vidocq's exploits; and if the remaining three are of equal interest, [pg 431] the work will be one of the most extraordinary of our times. We scarcely remember a counterpart, although the Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux are of the same stamp. The fate of the latter work was curious enough. The manuscript was sent by the author from New South Wales, whither he had been transported. It was printed in two small volumes, and published by an eminent west-end bookseller, who, for some unexplained motive withdrew the edition, which is, we believe, now in the printer's warehouse. The Editor of the "Autobiography" has, however, reprinted Vaux's memoirs in his series; their style is very superior to that of Vidocq's, (which is a translation) and as scores of worse books are printed annually, we rejoice at their rescue from oblivion.]

Remarkable instances are related of the manner in which Whitfield impressed his hearers. A man at Exeter stood with stones in his pocket, and one in his hand, ready to throw at him; but he dropped it before the sermon was far advanced, and going up to him after the preaching was over, he said, "Sir, I came to hear you with an intention to break your head; but God, through your ministry, has given me a broken heart." A ship-builder was once asked what he thought of him. "Think!" he replied, "I tell you, sir, every Sunday that I go to my parish church, I can build a ship from stem to stern under the sermon; but, were it to save my soul, under Mr. Whitfield I could not lay a single plank." Hume pronounced him the most ingenious preacher he had ever heard; and said, it was worth while to go twenty miles to hear him. But, perhaps, the greatest proof of his persuasive powers was, when he drew from Franklin's pocket the money which that clear, cool reasoner had determined not to give; it was for the orphan-house at Savannah. "I did not," says the American philosopher, "disapprove of the design; but as Georgia was then destitute of materials and workmen, and it was proposed to send them from Philadelphia at a great expense, I thought it would have been better to have built the house at Philadelphia, and brought the children to it. This I advised; but he was resolute in his first project, rejected my counsel, and I therefore refused to contribute. I happened, soon after, to attend one of his sermons, in the course of which I perceived he intended to finish with a collection, and I silently resolved he should get nothing from me. I had in my pocket a handful of copper money, three or four silver dollars, and five pistoles in gold. As he proceeded I began to soften, and concluded to give the copper; another stroke of his oratory made me ashamed of that, and determined me to give the silver; and he finished so admirably, that I emptied my pocket wholly into the collector's dish, gold and all.

"At this sermon," continues Franklin, "there was also one of our club, who, being of my sentiments respecting the building in Georgia, and suspecting a collection might be intended, had, by precaution, emptied his pockets before he came from home; towards the conclusion of the discourse, however, he felt a strong inclination to give, and applied to a neighbour who stood near him, to lend him some money for the purpose. The request was fortunately made to perhaps the only man in the company who had the firmness not to be affected by the preacher. His answer was, 'At any other time, friend Hopkinson, I would lend to thee freely; but not now, for thee seems to me to be out of thy right senses.'"

One of his flights of oratory, not in the best taste, is related on Hume's authority. "After a solemn pause, Mr. Whitfield thus addresses his audience:—'The attendant angel is just about to leave the threshold, and ascend to heaven; and shall he ascend and not bear with him the news of one sinner, among all the multitude, reclaimed from the error of his ways!' To give the greater effect to this exclamation, he stamped with his foot, lifted up his hands and eyes to heaven, and cried aloud, 'Stop, Gabriel! stop, Gabriel! stop, ere you enter the sacred portals, and yet carry with you the news of one sinner converted to God!'" Hume said this address was accompanied with such animated, yet natural action, that it surpassed any thing he ever saw or heard in any other preacher.—Southey.

Was very rough and harsh in manner. He said to a patient, to whom he had been very rude, "Sir, it is my way."—"Then," replied the patient, pointing to the door, "I beg you will make that your way." Sir Richard was not very nice in his mode of expression, and would frequently astonish a patient with a volley of oaths. Nothing used to make him swear more than the eternal question, "What may I eat? Pray, Sir Richard, may I eat a muffin?"—"Yes, Madam, the best thing you can take."—"O dear! I am glad of that. But, Sir Richard, [pg 432] you told me the other day that it was the worst thing I could eat!"—"What would be proper for me to eat to-day?" says another lady.—"Boiled turnips."—"Boiled turnips! you forget, Sir Richard, I told you I could not bear boiled turnips."—"Then, Madam, you must have a—vitiated appetite."

Sir Richard, being called to see a patient who fancied himself very ill, told him ingenuously what he thought, and declined prescribing, thinking it unnecessary. "Now you are here," said the patient, "I shall be obliged to you, Sir Richard, if you will tell me how I must live, what I may eat, and what not."—"My directions as to that point," replied Sir Richard, "will be few and simple. You must not eat the poker, shovel, or tongs, for they are hard of digestion; nor the bellows, because they are windy; but any thing else you please!"

He was first cousin to Dr. John Jebb, who had been a dissenting minister, well known for his political opinions and writings. His Majesty George III. used sometimes to talk to Sir Richard concerning his cousin; and once, more particularly, spoke of his restless, reforming spirit in the church, in the university, physic, &c. "And please your Majesty," replied Sir Richard, "if my cousin were in heaven he would be a reformer!"—Wadd's Memoirs.

"A snapper-up of unconsidered trifles."

SHAKESPEARE.

When from the friend we dearly love

Fate tells us we must part,

By speech we can but feebly prove

The anguish of the heart.

And no soft words, howe'er sincere,

Can half so much imply,

As that suppress'd, though trembling tear,

Which drowns the word—Good bye.

Warwick. W.S.

A keen shopkeeper, having in his service a couple of shopmen, who in point of intellect, were the very reverse of their master, a wag who frequented the shop, for some time puzzled the neighbourhood by designating it a "music-shop," although the proprietor dealt as much in music as in millstones. However, being pressed for an explanation, he said that the scale was conducted by a sharp, a flat and a natural; and if these did not constitute "music," he did not know what did.

ISSACCAR.

Napoleon being in the gallery of the Louvre one day, attended by Baron Denon, turned round suddenly from a fine picture, which he had viewed for some time in silence, and said to him, "That is a noble picture, Denon."—"Immortal," was Denon's reply. "How long," inquired Napoleon, "will this picture last?" Denon answered, that, "with care and in a proper situation, it might last, perhaps, five hundred years."—"And how long," said Napoleon, "will a statue last?"—"Perhaps," replied Denon, "five thousand years."—"And this," returned Napoleon, sharply, "this you call immortality!"

Let heroes, anxious for their future fame,

Obtain of Fortune what they want—a name;

The future theirs, the present hour be mine—

The only name I ask of fate—is thine;

Yet happier still had fate decreed to me

The favour'd lot, to give my name to thee.

T.B.

A dull barrister, once obtained the nickname Necessity—because Necessity has no law.

PURCHASERS of the MIRROR, who may wish to complete their sets are informed that every volume is complete in itself and may be purchased separately. The whole of the numbers are now in print, and can be procured by giving an order to any Bookseller or Newsvender.

Complete sets Vol I. to XI; in boards, price £2. l9s. 6d half bound, £3. l7s.

The ARABIAN NIGHTS' ENTERTAINMENTS. Embellished with nearly 150 Engravings. Price 6s. 6d. boards.

The TALES of the GENII. Price 2s.

The MICROCOSM By the Right Hon. G. CANNING. &c. Price 2s.

PLUTARCH'S LIVES, with Fifty Portraits, 2 vols. price l3s. boards.

COWPER'S POEMS with 12 Engravings, price 3s. 6d. boards.

COOK'S VOYAGES, 2 vols. price 8s. boards.

The CABINET of CURIOSITIES: or, WONDERS of the WORLD DISPLAYED Price 5s. boards.

BEAUTIES of SCOTT. 2 vols. price 7s. boards.

The ARCANA of SCIENCE for 1828. Price 4s. 6d.

Any of the above Works can be purchased in Parts.

GOLDSMITH'S ESSAYS. Price 8d.

DR. FRANKLIN'S ESSAYS. Price 1s. 2d.

BACON'S ESSAYS, Price 8d.

SALMAGUNDI, Price 1s. 8d.

Footnote 1: (return)Cavendish's Life of Wolsey, p. 1. edit. 1641. Most of his biographers affirm that he was the son of a butcher.

Footnote 2: (return)"Northern Tour." The same author observes, that "the death of Wolsey would make a fine moral picture, if the hand of any master could give the pallid features of the dying statesman, that chagrin, that remorse, those pangs of anguish, which, in the last bitter moments of his life, possessed him. The point might be taken when the monks are administering the comforts of religion, which the despairing prelate cannot feel. The subject requires a gloomy apartment, which a ray through a Gothic window might just enlighten, throwing its force chiefly on the principal figure, and dying away on the rest. The appendages of the piece need only be few and simple; little more than the crozier and red hat to mark the cardinal and tell the story."

Footnote 3: (return)Stow's "Annals," p. 557, edit. 1615.

Footnote 4: (return)Shakspeare introduces this memorable saying of the cardinal into his play of "Henry the Eighth:"—

—"O Cromwell, Cromwell,

Had I but serv'd my God with half the zeal

I serv'd my king, he would not in mine age

Have left me naked to mine enemies."

Footnote 5: (return)Stow's "Annals."

Footnote 6: (return)Holinshed's "Chronicle," vol. iii. p. 765, edit. 1808.

Footnote 7: (return)"Collectanea," vol i. p. 70.

Footnote 8: (return)Tanner.

Footnote 9: (return)For the particulars of which, see Knolle's "history of the Turks."

Footnote 10: (return)Azrael, in the Mahometan creed, the angel of death.

Footnote 11: (return)The present portion is only the first volume. The Memoirs are to be completed in four volumes, to form part of the series of Autobiographical Memoirs, published by Messrs. Hunt and Clarke, and decidedly one of the most attractive works that that has lately issued from the press. As we intend to notice this collection at some future time, we can only, for the present, spare room for this direction of the reader's attention—for the design deserves well of the public; and if the success be proportioned fro its merits, it will be great indeed.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD 143, Strand. (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mirror of Literature, Amusement,

and Instruction., by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MIRROR OF LITERATURE, NO. 347 ***

***** This file should be named 11386-h.htm or 11386-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/1/3/8/11386/

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Gil, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be