The Project Gutenberg EBook of Highroads of Geography, by Anonymous This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Highroads of Geography Author: Anonymous Release Date: February 21, 2004 [EBook #11218] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HIGHROADS OF GEOGRAPHY *** Produced by Julie Barkley, Susan Woodring and PG Distributed Proofreaders

That's where Daddy is!

(From the painting by J. Snowman.)

1. Father kissed us and said, "Good-bye, dears. Be good children, and help mother as much as you can. The year will soon pass away. What a merry time we will have when I come back again!"

2. Father kissed mother, and then stepped into the train. The guard blew his whistle, and the train began to move. We waved good-bye until it was out of sight.

3. Then we all began to cry—even Tom, who thinks himself such a man. It was so lonely without father.

4. Tom was the first to dry his eyes. He turned to me and said, "Stop that crying. You are the eldest, and you ought to know better."

5. He made mother take his arm, just as father used to do. Then he began to whistle, to show that he did not care a bit. All the way home he tried to make jokes.

6. As soon as we had taken off our coats and hats, Tom called us into the sitting-room. "Look here," he said: "we're going to have no glum faces in this house. We must be bright and cheerful, or mother will fret. You know father wouldn't like that."

7. We said that we would do our best. So off we went to help mother to make the beds and to dust the rooms. While we were doing this we quite forgot to be sad.

8. After tea we went into father's room and looked at the globe. "I'm going to follow father right round the world," said Tom. "Please show me which way he is going." Mother did so.

9. "By this time next week," she said, "we shall have the first of many long letters from father. I am sure we shall enjoy reading them. He will tell us about the far-off lands which he is going to see."

10. "That will be grand," I said. "I hope he will tell us lots about the children. I want to know what they look like, what they wear, and what games they play."

11. Tom said he would rather not hear about children. He wanted to hear about savages and tigers and shipwrecks, and things like that.

12. A week later the postman brought us father's first letter. How eager we were to hear it! Mother had to read it for us two or three times.

13. Every week for many weeks the postman brought us letters from father. When he handed us a letter he used to say, "I'm glad to see that your daddy is all right so far."

14. This book is made up of father's letters from abroad. I hope you will enjoy them as much as we did.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—I am writing this letter in a large seaport of the south of France. To-morrow I shall go on board the big ship which is to take me to Egypt.

2. Let me tell you about my travels so far. The train in which I left our town took me to London. Next day another train took me to a small town on the seashore.

The White Cliffs of Dover.

(From the picture by J.M.W. Turner, R.A.)

3. About twenty miles of sea lie between this town and France. At once I went on board the small steamer which was to take me across. The sea was smooth and the sun was shining.

4. I stood on the deck looking at the white cliffs of dear old England. When I could see them no longer I found that we were not far from France.

5. In about an hour we reached a French town which in olden days belonged to us. The steamer sailed right up to the railway station.

6. I had something to eat, and then took my place in the train. Soon we were speeding towards Paris, the chief town of France.

7. I looked out of the window most of the time. We ran through many meadows and cornfields. Here and there I saw rows of poplar trees between the fields.

8. Now and then we crossed rivers with barges on them. On and on we went, past farmhouses and little villages, each with its church. The French villages look brighter than ours. I think this is because the houses are painted in gay colours.

9. I saw many men, women, and children working in the fields. All of them wore wooden shoes. Most of the men and boys were dressed in blue blouses.

10. There was a little French boy in my carriage. He wore a black blouse with a belt. His stockings were short, and did not come up to his knickerbockers. He was rather pale, and his legs were very thin.

11. The boy was about Tom's age. He sat still, and held his father's hand all the way. I don't think Tom would have done this; he thinks himself too much of a man.

12. After a time we crossed a broad river, and came to the dull, dark station of a large city. As we left it, I saw the tall spire of one of the grandest churches in all the world.

13. On we went, past farms and villages and small towns, until at last we reached Paris.

In the Gardens.

(From the picture by Cyrus Cuneo, R.I.)

1. Paris is a very grand and beautiful city. The French people say that France is a great garden. They also say that the finest flowers in this garden make up the nosegay which we call Paris.

2. A great river runs through Paris. All day long you can see little steamboats darting to and fro on the river, like swallows. Near to the river are some beautiful gardens.

3. I sat in these gardens, at a little table under the trees. As I sat there a man walked up the path. At once I heard a great chirping and a flutter of wings.

4. All the birds in the garden flocked to him. They seemed to know him as an old friend. Some perched on his shoulders and some on his hat. One bold little fellow tried to get into his pocket. It was a pretty sight to see him feeding the birds.

5. In the gardens there were many nurses carrying babies. These nurses were very gay indeed. They wore gray cloaks and white caps, with broad silk ribbons hanging down their backs.

6. Some of the older children were playing ball, but they did not play very well. Until a few years ago French boys had few outdoor games. Now they are learning to play tennis and football.

7. French boys are always clean and neatly dressed, however poor they may be. They think more about lessons than our boys do. Their school hours are much longer than ours.

8. French girls have not so much freedom as our girls. A grown-up person takes them to school and brings them home again. Their mothers do not allow them to go for walks by themselves. I wonder how Kate and May would like this.

9. Some day I must take you to see Paris. You would love to ramble through its streets. Many of them are planted with trees. Under these trees you may see men and women sitting at little tables. They eat and drink while a band plays merry tunes.

10. You would be sure to notice that the French people have very good manners. When a Frenchman enters or leaves a shop he raises his hat and bows. A Frenchman is always polite, and he always tries to please you.

11. I cannot now write anything more about Paris. I should like to tell you about its beautiful buildings and its fine shops, but I have no more time to spare.

12. I hope you are all doing your best to make mother happy. I am very well; I hope you are well too.—Your loving FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—I am writing this letter on board the big ship which is taking me to Egypt. Let me tell you what I have seen and done since I left Paris.

2. It is a long day's ride from Paris to the seaport from which my ship set sail. Let me tell you about the journey. A few hours after leaving Paris the train began to run through vineyards.

3. At this time of the year a vineyard is a pretty sight. The broad leaves of the vine are tinted with crimson and gold. Beneath them are the purple or golden grapes.

THE GRAPE HARVEST.

(From the picture by P.M. Dupuy in the Salon of 1909.

Bought by the State.)

4. As I passed through France the grapes were ripe, and were being gathered. I could see women and children going up and down between the rows of vines. They plucked the ripe fruit and put it into baskets. When the baskets were filled they were emptied into a big tub.

5. When the tub was filled it was taken to a building near at hand. In this building there is a press which squeezes the juice out of the grapes. The grape juice is then made into wine.

6. As evening drew on we came to a large town where two big rivers meet. It is a busy town, and has many smoky chimneys. Much silk and velvet are made in this town.

7. I think you know that silk is made by the silkworm. This worm feeds on the leaves of the mulberry tree. In the south of France there are thousands of mulberry trees. There are also many orange and olive trees.

8. The weather is much warmer in the south of France than it is in England. In the early spring all sorts of pretty flowers are grown on the hillsides. They are sent to England, and are sold in the shops when our gardens are bare.

9. Now I must hurry on. For some hours we ran by the side of a swift river; with mountains on both sides of us. Then we reached the big seaport, and there I found my ship waiting for me.

GAMES ON BOARD FATHER'S SHIP.

(From the picture by W.L. Wylie. By kind permission of

the P. and O. Co.)

10. It is a huge ship, with hundreds of cabins, a large dining-room, drawing-room and smoking-room. It is really a floating hotel.

11. Most of the people on board are going to India. All day long they sit in chairs on the deck reading. Some of us play games, and at night we have dances and concerts.

12. We have now been four days at sea. To-morrow we shall reach a town by the side of a great canal. This town and canal are in Egypt.

13. I hope you are still good and happy.—Best love to you all. FATHER.

The Nile in Flood.

(From the picture by F. Goodall, R. A., in the

Guildhall Gallery. By permission of the Corporation of

London.)

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—With this letter I am sending you a beautiful picture. Look at it carefully, and you will see what Egypt is like.

2. The water which you see in the picture is part of the great river Nile. If there were no Nile to water the land, Egypt would be nothing but a desert.

3. Once a year, as a rule, the Nile rises and overflows its banks. The waters spread out over the country and cover it with rich mud. In this mud much cotton, sugar, grain, and rice are grown.

4. Egypt now belongs to the British. They have turned part of the Nile into a huge lake, in which the water is stored.

5. The water is let out of the lake when it is needed. It runs into canals, and then into drains, which cross the fields and water them.

6. A sail along the Nile is very pleasant. There are lovely tints of green on the water. As the boat glides on, many villages are passed. Each of these has its snow-white temple.

7. All along the river bank there are palm trees. They wave their crowns of green leaves high in the air. The fields are gay with colour. Above all is the bright blue sky.

The Chief City of Egypt.

(From the picture by Talbot Kelly, R.I.)

8. Look at the picture again. At a short distance from the water you see a village. It has a wall round it, and outside the wall is a ditch. In October the ditch is full of water; in spring it is dry.

9. In and near this ditch the children and the dogs of the villages play together. You can see two boys in the picture. One of them is standing by his mother. The other boy is riding on a buffalo.

10. In the middle of the village there is an open space. Sometimes this space is covered with bright green grass. Round it are rows of palm trees. The house of the chief stands on one side of this green.

11. Every village has its well, and every well has its water-wheel for drawing up the water. By the side of the well the old men of the village sit smoking and chatting. The women come to the well to fill their pitchers with water.

12. All the houses are built of Nile mud. This mud is dug out of the banks of the river. It is mixed with a little chopped straw to hold it together. Then it is put into moulds. After a time it is turned out of the moulds, and is left to dry in the sun.

1. In the picture you see two of the women of Egypt. One of them is standing at the edge of the river. She is filling her pitcher with water. The other woman is carrying a lamb in her arms.

2. The people of Egypt have changed but little since the days of Moses. The men have brown faces, white teeth, and bright black eyes. Most of them wear beards and shave their heads.

3. The women wear long dark cloaks. If they are well-to-do they cover their faces with a veil. They think it wrong to let their faces be seen by any men except their husbands.

4. I think Kate would like to hear something about the children. Those who have rich fathers wear beautiful clothes, and have a very happy time. Poor children wear few clothes, and are nearly always covered with dust.

5. Many of the boys go to school, and are taught just as you are. They read the same kind of books that you read.

6. The children of Egypt always obey their parents, and are never rude to them. I think they have very good manners.

7. All the people of Egypt love singing. Their voices are soft and sweet. The boatmen on the Nile sing as they row. The fruit-sellers sing as they cry their wares in the streets.

8. Many of the boys in the chief city of Egypt are donkey drivers. In Egypt donkeys are far more used for riding than horses. The donkeys are beautiful little animals, and they trot along very quickly.

9. Each donkey has a boy to run after it with a stick, and to shout at it to make it go. The donkey boys are very jolly little fellows. They always smile, however far they have to run.

10. Most donkey boys wear a white or blue gown, and have a red cap, or fez, on the head. If a donkey boy sees an Englishman coming, he runs to him and says, "My donkey is called John Bull." If he sees an American coming, he says that his donkey's name is Yankee Doodle.

11. Sometimes the donkey boy will ask the rider,—

"Very good donkey?"

If the rider says "Yes," he will then ask,—

"Very good donkey boy?"

"Yes."

12. "Very good saddle too?"

"Yes."

"Then me have very good present!"

13. Now let me tell you something that will surprise you. The people of Egypt in the old, old days thought that their cats were gods.

14. They prayed to them and built temples to them. When the family cat died, all the people in the house shaved their eyebrows to show how sorry they were.—Best love to you all. FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—I have just sailed through a very wonderful canal. It joins two great seas together, and is now part of the way to India.

2. By means of this canal we can sail from England to India in three weeks. Before it was made the voyage took three months or more.

3. The canal was made more than forty years ago by a Frenchman. He dug a great ditch, and joined together a number of lakes. By doing so he made a waterway from sea to sea. This waterway is about a hundred miles long.

4. I joined my ship at the town which stands at the north end of the canal. There is nothing to see in the town except the lighthouse and the shops. On the sea wall there is a statue of the Frenchman who made the canal.

5. As we lay off the town we could see many little boats darting to and fro. The boatmen were dressed in all the colours of the rainbow—red, blue, green, and orange. In one boat there were men and women playing and singing songs.

6. By the side of our ship men were swimming in the water. I threw a piece of silver into the water. One of the men dived, and caught it before it reached the bottom.

7. On the other side of the ship there were great barges full of coal. Hundreds of men and women carried this coal to the ship in little baskets upon their heads. They walked up and down a plank, and all the time they made an awful noise which they called singing.

8. When all the coal was on board, the ship began to steam slowly along the narrow canal. No ship is allowed to sail more than four miles an hour, lest the "wash" should break down the banks.

9. Soon we passed out of the narrow canal into one of the lakes. Our road was marked by buoys. Away to right and to left of us stretched the sandy desert.

10. In the afternoon we passed a station, where I saw a number of camels laden with boxes of goods. They were going to travel across the sands for many days.

11. The sun went down in a sky of purple and gold. Then a large electric light shone forth from our bows. It threw a broad band of white light on the water and on the banks of the canal. Where the light touched the sands it seemed to turn them into silver.

12. In less than twenty-four hours we reached the town at the south end of the canal. A boat came out from the shore, and this letter is going back with it.—Love to you all. FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—I am now sailing along the Red Sea. The weather is very hot. All over the ship electric fans are hard at work. In spite of them I cannot keep cool.

2. Away on the left, or port, side of the ship I see high hills. They are red in colour, and seem to be baked by the hot sun. Even through my spy-glass I cannot see a speck of green on them. All is red and bare.

3. Beyond the hills lies the land of Arabia. It is a hot, dry land, in which years sometimes pass without a shower of rain. There is hardly ever a cloud in the sky, and there is no dew at night.

4. Much of the land is covered with sand. Little or nothing will grow. You know that we call a sandy waste of this kind a desert.

5. Here and there in the desert a few springs are found. The water of these springs causes grass and trees to grow well. Around each spring is what looks like an island of green in the midst of a red sea of sand. A green spot in a desert is called an oasis.

6. The Arabs live upon these green spots. Some of them dwell in villages, and some wander from oasis to oasis. Those who live in villages build their houses of sun-dried bricks; those who wander from place to place live in tents.

7. The Arabs are fine, fierce-looking men. They own flocks of sheep, herds of goats, camels and horses.

8. An Arab's tent is woven out of camel's hair. So are the ropes of the tent. The poles are made of palm wood.

9. Inside the tent there are leather buckets for drawing water. There are also skin bags for carrying it across the desert. There are no chairs or tables or beds in the tents. The Arabs squat upon the ground and sleep on rugs.

10. In front of an Arab tent you are almost sure to see a woman grinding corn between two large stones. There is a hole in the top stone, and into this she pours the grain.

11. She turns the top stone round and round, and the grain is ground into flour, which oozes out at the edges. With this flour she makes cakes.

Arabs of the Desert.

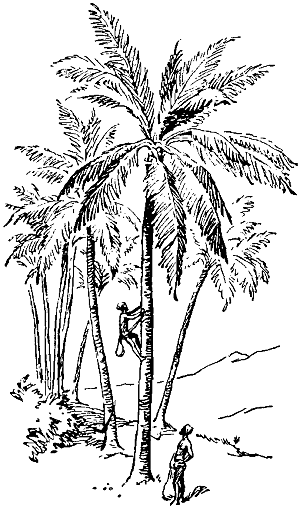

1. Date palms grow on every oasis. The date palm is a beautiful tree. It is very tall, and has a crown of leaves at the top.

2. The fruit grows in great golden clusters. Sometimes a cluster of dates weighs twenty-five pounds.

3. The date palm is beloved by the Arabs, because it is so useful to them. They eat or sell the dates, and they use the wood for their tents or houses. From the sap they make wine. Out of the leaf-stalks they weave baskets.

4. Some of the Arabs are traders. They carry their goods from oasis to oasis on the backs of camels. A large number of laden camels form a caravan.

5. A camel is not pretty to look at, but the Arab could not do without it. I think you can easily understand why the camel is called the "ship of the desert." It carries its master or its load across the sea of sand from one green island to another.

6. The hoofs of the camel are broad, and this prevents them from sinking into the sand. The camel can go for a long time without food or water.

7. The camel is very useful to the Arab, both when it is alive and when it is dead. It gives him milk to drink, and its hair is useful for making clothes, tents, and ropes.

The Halt in the Desert.

(From the picture by J.F. Lewis, R.A., in the South

Kensington Museum.)

8. I think I told you that when I was sailing along the canal I saw a caravan. It was then beginning to cross the desert. Very likely, weeks or months will pass away before its journey comes to an end.

9. There are no roads across the desert, so it is very easy for a caravan to lose its way. Then the men and camels wander on until all their food and water are finished. At last they fall to the ground, and die of hunger and thirst.

10. Dreadful sand-storms often arise. The storm beats down upon the caravan, and sometimes chokes both men and camels. A journey across the desert is full of dangers.

11. Before I close this letter, let me tell you a little story. One day an Arab belonging to a caravan overslept himself at an oasis. When he awoke, the caravan had started on its journey again, and was many miles away.

12. The Arab followed the caravan, in the hope of catching it up. On and on he walked, but nothing could he see of it. Then darkness came on, and he lay on the sand and slept until morning.

13. When the sun rose he began his journey again. Hours passed, but still there was no sign of the caravan. At last he was quite overcome by hunger and thirst. He fell to the ground, and was too weak to rise again.

14. Looking around, he saw something black lying on the sand, not far away. He crawled to it, and found that it was a small bag which had fallen from the back of a camel.

15. The poor Arab was filled with joy. He hoped that the bag would contain food of some sort. With trembling fingers he tore it open. Alas! it was full of gold and jewels.

16. "Woe is me!" cried the poor fellow; "had it been dates my life would have been saved."

17. This little story shows you that on the desert dates may sometimes be worth much more than gold and jewels. I hope you are well and happy.—Your loving FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—Hurrah! I am on shore again, after nine long days at sea. Yesterday I reached Bombay, the chief seaport of India.

2. Soon after I landed a friend came to see me at my hotel. He drove me round Bombay, and showed me all the sights. I wish you had been with me to see them.

3. Here in Bombay I seem to be in a new world altogether. It is a world of wonderful light and colour. The bright hot sun floods the streets and dazzles my eyes. Everywhere I see bright colour—in the sky, the trees, the flowers, and the dresses of the people.

4. The streets are always full of people. They are dark brown in colour; their hair is black, their eyes are bright, and their teeth are as white as pearls. Most of the people are bare-legged and bare-footed.

5. The men wear white clothes, with turbans and sashes of yellow, green, or blue. Yesterday was a feast-day. In the morning I saw thousands of the people bathing in the sea. Afterwards they roamed about the streets in their best clothes. One crowd that I saw looked like a great tulip garden in full bloom.

6. The women wear a garment of red, blue, or some other bright colour. This garment covers them from the neck to the knee. Almost every woman wears rings of silver on her arms and ankles. Some of them have great rings in their noses, as well as rings in their ears and on their toes.

7. You would be amused to see the people carrying their burdens on their heads. Yesterday I saw a dozen men carrying a grand piano on their heads.

8. From childhood the women carry jars of water or baskets of earth in this way. They hold themselves very upright and walk like queens.

9. Bombay is a very busy city. The streets are thronged with carriages, motor cars, bullock carts, and electric trams. As the people walk in the middle of the road, it is not easy for a carriage to make its way through the streets.

10. The drivers ring bells, or shout to warn the people: "Hi, you woman with the baby on your hip, get out of the way!—Hi, you man with the box on your head, get out of the way!"

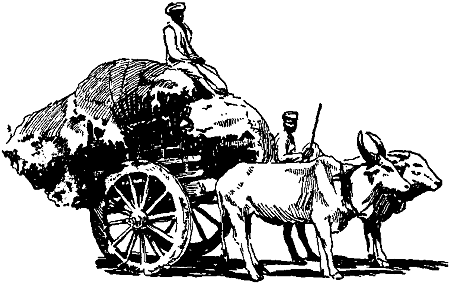

11. I think you would like to see the bullock carts. They are very small, and are drawn by two bullocks with humps on their shoulders. The driver sits on the shaft and steers them with a stick. These carts carry cotton to the mills or to the docks.

12. In some of the carriages and motor cars you may see rich men wearing fine silk robes. Many of these rich men now dress as we do, except that they wear turbans instead of hats.

1. I should like you to see the shops of Bombay. Most of them are quite unlike our British shops. They have no doors and no windows, but are open to the street.

2. Our shopkeepers try to make a fine show of their goods. The Indian shopkeeper does nothing of the sort. He simply piles his goods round his shop and squats in the midst of them. There he sits waiting for people to come and buy.

3. In our shops there is a fixed price for the goods. In India nothing has a fixed price. You must bargain with the shopkeeper if you wish to buy anything. Very likely he will ask you three times the price which he hopes to get.

4. Our penny is divided into four parts; each of these parts is called a farthing. The Indian penny is divided into twelve parts; each of these parts is called a "pie." An Indian boy or girl can buy rice or sweets with one pie.

5. There are thousands of beggars in India. They go to and fro in front of the shops begging. The shopkeepers are very kind to them, and never send them away without a present.

6. Very good order is kept in the streets. At every street corner stands a native policeman, dressed in blue, with a flat yellow cap on his head and a club by his side. Some of the policemen ride horses, and carry guns and lances.

7. The parks of Bombay are large open spaces covered with grass. Round them are rows of palm trees. In these parks you may see men and boys playing all sorts of games.

8. Indians are very fond of cricket, which they play very well. Not many years ago an Indian prince was one of the best players in England.

9. Polo is also played in the parks of Bombay. It is an Indian game, but Britons now play it too. Polo is just hockey on horseback.

10. The players ride ponies which are very quick and nimble. Each player carries a mallet with a very long handle. With this mallet he strikes a wooden ball and tries to drive it between the goal posts.

11. Last night I stopped to watch some Indian boys playing marbles. When Tom plays the game, he places the marble between his thumb and forefinger and shoots it out with his thumb.

12. The Indian boy does not shoot the marble in this way at all. He presses back the second finger of one hand with the forefinger of the other. Then he lets go and strikes the marble with the finger that was bent back. Some of the boys are very clever at this game.

13. Bombay has some very fine buildings. On the top of most of them you see the Union Jack, the flag of Britain. Not only Bombay but all India belongs to Britain. I hope you are all well.—Best love. FATHER.

The Village Well.

(From the picture by W. Simpson, R.I.)

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—I am now in the north of India, not far from the great river Ganges. It is a long railway journey from Bombay to this place. I have been in the train two days and two nights.

2. I am now beginning to understand what a vast land India is. Do you know that it would make sixteen lands as large as our own? One in every five of all the people on earth lives in India.

3. Perhaps you can guess why I have made this long journey from Bombay. My brother, your uncle, is the chief man in this part of the country. He and I have been parted for many years. I am now living in his house.

4. Let me tell you about little Hugh, your cousin. He was born in India seven years ago, and he has never been to England. He hopes to come "home" to see you all in a few months' time.

5. Hugh's home is a big house, all on the ground floor. It has no upstairs. The rooms are very large and lofty. This is because the weather is very hot for the greater part of the year. If the rooms were not large and high, they would be too hot to live in.

6. In every room there is a beam of wood with a short curtain hanging from it. This is the punkah. The beam is hung from the roof by ropes. In the hot weather a boy sits outside and pulls the punkah to and fro with a rope. In this way he makes a little breeze, which keeps the room cool.

7. The roof of the house juts out all round and is held up by pillars. We sit outside, under the roof, whenever we can. During the heat of the day we must stay indoors.

8. The garden round the house is very large. There are many tall palm trees in it. Some of the other trees bear most beautiful blossoms of crimson, yellow, and blue. All along the front of the house are many flowerpots, in which roses and other English flowers are growing.

9. A few days ago little Hugh came to me and asked if he might show me what he called "the compound." I said "Yes." So he took my hand and led me away.

10. First he showed me the gardener. He is a short, dark man, and he squats down to do his work. He is a very good gardener, and he is proud of his flowers. Every morning he comes to the house with a flower for Hugh's father and mother and uncle.

11. Next, Hugh took me to see the well. It is behind the house. The mouth of the well is on the top of a mound. To reach it you must walk up a sloping road. Above the mouth of the well there is a wheel.

12. A rope runs over this wheel. At one end of the rope there is a large leather bag. The other end of the rope is fastened to the necks of a pair of bullocks.

1. The bullocks walk backwards up the sloping road. This lowers the leather bag into the well, where it is filled with water. Then the bullocks walk down the sloping road. This pulls the bag up to the mouth of the well.

2. A man empties the water out of the bag into a tank by the side of the well. The water runs out of this tank into the garden, where it spreads out into many little streams. It is this water which makes the trees, the plants, and the grass grow so well in the garden.

3. If the garden were not watered in this way, it would soon be brown and bare. For many months at a time no rain falls in India. Then dust a foot deep lies on the roads, and the ground cracks with the heat.

4. When the dry season is over the rain begins to fall. It comes down in torrents for days together. In some places more rain falls in a single day than we have in a whole year.

5. During the "rains" the rivers become full to the brim, and the whole land is fresh and green. Sometimes the "rains" do not come at all. Then the crops wither away, and the people starve.

6. In our country we are never sure of the weather. It changes so often that we talk about it a great deal. In India nobody talks about the weather. During seven months of the year every day is fine.

7. In our country we almost always have plenty of water for our crops, and for drinking and washing. Plenty of fresh water is a great blessing to a land. In many parts of India water is very scarce.

8. I told you that the great river Ganges is not far away from little Hugh's home. This grand river begins in the mountains of North India. I wish you could see these mountains. They are the highest on earth. They rise up from the plains like a huge wall, and their tops are always covered with fields of ice and snow.

9. These ice-fields slowly move down the mountain sides. Then they melt, and this gives rise to the Ganges and to the other great rivers of North India.

10. Millions of the Indian people love the Ganges, and they have good reason to do so. It gives water and food to more than twice as many people as dwell in the British Islands.

11. Many Indians think that every drop of water in the river is holy. They believe that if they bathe in its waters their souls will be washed clean from sin.

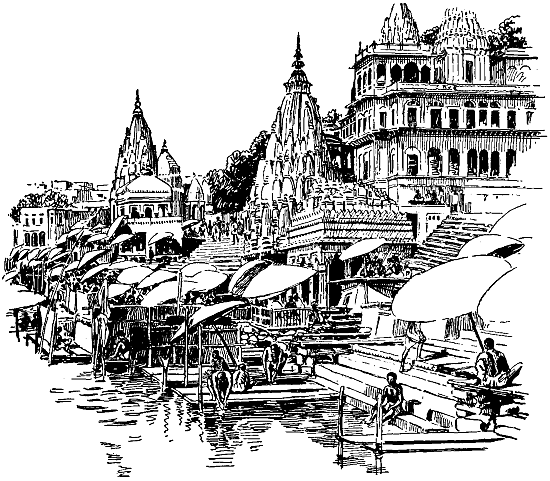

12. There is a town by the side of the Ganges which the Indians say is the holiest place on earth. It is full of temples. Millions of Indians visit these temples every year.

13. All along the river bank there are stone steps leading down to the water. Standing in the stream are men and women and children who have come from all parts of India. They wash themselves in the stream, and pour the holy water over their heads as they pray.

14. People who are very ill are carried to this place, that they may die by the side of "Mother Ganges." They die happy if they can see her or hear the sound of her waters during their last moments.

15. When they die their bodies are taken to the steps. There they are washed in the river water, and are placed on piles of wood. Friends set fire to the wood, and soon the bodies are burnt to ashes. These ashes are thrown into the stream, which bears them to the distant ocean.

1. I am very fond of going about the streets with your uncle. The Indian children always amuse me.

2. When Indians grow up they are rather grave and sad. The children, however, are always bright and merry. Indian fathers and mothers are very fond of their boys. They care very little for their girls.

3. Boys soon become men in India. They begin work at an early age, and they are married when they are about sixteen. Girls are married a few years younger.

4. Almost every boy follows the trade of his father. A farmer's son becomes a farmer, a weaver's son becomes a weaver, and so on.

5. Many of the boys go to school, but not many of the girls. They, poor things, begin to work in the house or in the field almost as soon as they can walk. Much of the hard rough work in India is done by poor women and girls.

6. A rich father keeps his girls shut up in the back part of his house. Their faces are never seen by any man except those of their own family. If they go out of the house, they cover themselves from head to foot with a thick veil. Sometimes they are carried from place to place in a closely shut box on poles.

7. Are you not sorry for these poor rich girls? I am. They can never play merry games with boy friends, or go for long walks in the country.

8. They know nothing of the beautiful world in which they live. Their rooms are fine, their dresses are grand, and their jewels are lovely; but they are only poor prisoners after all.

9. Yesterday I went with your uncle to see a village school. There were only twenty boys in it. The roof was off the schoolhouse, so the classes were held in the open air.

10. The boys sat on forms, just as you do. The teacher wrote on a blackboard, and taught the children to do sums with a ball frame. Each boy had a reading-book. It was not printed in English, but in the tongue spoken in that part of the country.

11. Some of the boys wrote in copy-books, but most of them wrote on thin boards, which they used instead of slates. Instead of a pencil they used a pen made of a reed.

12. Chalk was ground up and wetted in a little cup. The boys dipped their reed pens into the cup, just as you dip your steel pen into the ink. The letters and figures which they wrote were very different from ours.

13. Some of the boys read their books very well, and worked hard sums. They sang "God save the King" for me in their own tongue.

14. In the towns there are large and good schools. Some of the scholars are very clever indeed. I think Indian boys are much fonder of their lessons than our boys.

AN INDIAN RAJAH.

1. In his last letter Tom asked me to tell him something about elephants and tigers. I will try to do so.

2. Yesterday your uncle and I went out to shoot pigeons. An Indian chief, or rajah, lent us an elephant to carry us to the shooting ground.

3. A driver sat on the neck of the huge animal. Instead of a whip he had a goad of sharp steel. I did not see him prick the elephant with this goad. He guided the animal with voice and hand.

4. On the elephant's back there was a large pad upon which we were to sit. I could see no ladder, so I wondered how I was to climb up. Just then the elephant knelt down on his hind legs.

5. Your uncle showed me how to get up. "Here," he said, "is a ladder of two steps. The first step is the elephant's foot, the second is the loop of his tail."

6. He held the end of the elephant's tail in his hand and bent it to make a loop. When I put my foot on it he lifted the tail, and in this way helped me on to the elephant's back.

7. When your uncle had climbed up, the elephant jogged off at a good pace. He went along rough, narrow paths, over ditches and the beds of streams. Never once did he make a false step.

8. An elephant costs a great deal of money. Only princes and rich men can afford to keep them. Sometimes a great prince has as many as a hundred elephants in his stables.

9. When a prince rides through a city in state his elephants wear rich cloths, which are studded with gems. Sometimes the elephants' heads are painted and their tusks are covered with gold.

10. In the drawing-room of your uncle's house there is a beautiful tiger skin. The tiger that used to wear this skin was shot by your uncle about three years ago.

11. It was a man-eating tiger—that is, an old tiger that could no longer run fast enough to catch deer. This man-eater used to hide near a village. He would creep up silently behind men and women, and stun them with a blow of his paw. Then he would drag them away and eat them.

12. The people of the village came to your uncle and begged him to kill the man-eater. He agreed to do so. Near to the tiger's drinking-place a little hut was built in a tree. One night your uncle sat in this hut with his gun on his knee, waiting for the tiger to come.

13. Slowly the hours went by, and your uncle felt sure that the tiger had gone to another place to drink. Just as he was thinking of going home to bed the huge animal crept into the moonlight.

14. Nearer and nearer he came. Then your uncle lifted his gun, took a steady aim, and shot the tiger through the heart.

15. In the morning there was great joy among the people of the village because their fierce foe was dead. They hung garlands of flowers round your uncle's neck, and sang his praises in many songs.

16. Now I must close this very long letter.—Best love to you all. FATHER.

A Tiger Shoot.

(From the picture by Edgar H. Fischer, in the Royal

Academy, 1911.)

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—Since I last wrote to you I have visited several of the large cities of India. A week ago I was in the largest city of all.

2. On Christmas morning I sailed down the mouth of the Ganges into the open sea, on my way to the country of Burma.

3. Now I am in the chief town of Burma, and you will expect me to tell you something about the land and its people. From what I have seen, I think Burma is a prettier country than India.

4. In the chief town there seem to be people from many lands. I saw Chinamen, with their pigtails hanging down their backs. I also saw Indians from across the sea, and white men from our own country. Of course, there were also many Burmese, as the people of Burma are called.

5. Kate and May will like to hear something about the Burmese girls and women. They are not at all sad like the Indians, but are very bright and gay. As I write these lines I see a party of Burmese girls passing my window, I can hear them laughing.

6. They are very dainty in their dress. One girl wears a skirt of pink silk and a blouse of light green. She has bracelets on her arms, ear-rings in her ears, a string of coral round her neck, and flowers in her hair.

7. In one hand she carries a bamboo sunshade; in the other she holds a big paper cigar! She is very fond of smoking, and you never see her without a cigar. On her feet she wears sandals.

8. The men are gentle and rather lazy. The women have far more "go" in them than the men. Many of them keep shops, and are very good traders. The wife is the chief person in every home.

9. The men also wear skirts, and sometimes their jackets are very gay. They wrap a handkerchief of pink, or of some other bright colour, round their head.

10. The Burmese worship Buddha, a prince who lived more than two thousand years ago. He was a very noble man, and he gave up all the pleasant things of life that nothing might turn his thoughts from goodness.

11. Amongst other things he taught men to be kind to animals. All animals are well treated in Burma.

12. All over the land you see temples to Buddha. These temples grow narrower and narrower the higher they rise. They all end in a spire above which there is a kind of umbrella. It is made of metal, and all round its edge are silver or golden bells, which make pretty music as they are blown to and fro by the wind.

13. By the side of many of these temples you may see a great image of Buddha. Most of the images are made of brass. The Burmese pray before these images, and offer flowers and candles and rice to them.

1. Wherever you go in Burma you see monks. They have shaven heads, and they wear yellow robes. Every morning they go out to beg. Boys in yellow robes go with them, and carry large bowls in their hands.

2. The people come out of their houses and put food into the bowls. The monks do not thank them. They say that he who gives is more blessed than he who takes.

3. The monks live in houses built of teak wood. In every village you can see a monk's house standing in a grove of palm trees. In these houses the monks keep school.

4. Every Burmese boy lives for some time in one of the monks' houses. Here he learns to read and write, and is taught to be a good man.

5. I went to see the most beautiful of all the monks' houses. It is in a city far up in the country. The building is of dark-brown teak wood, and has many roofs, one above the other. It is covered with carving, and here and there it is gilded.

6. Many boys in yellow robes were playing beneath the trees. They were the scholars of the school. One of the boys told me that he was never going to leave the place. When he was old enough he meant to be a monk.

7. In the city I saw the palace of the king from whom we took Burma. It stands inside a large space, with high walls all round it. Outside the wall is a broad ditch full of water. When I saw the ditch it was overgrown with water-plants covered with pink blossoms.

8. Many buildings, something like the monks' houses, form the king's palace. Some of the buildings are very richly carved, and are covered with gold leaf. Inside one of them I saw great teak pillars, also covered with gold.

9. The chief building ends in a very lofty spire, with a beautiful metal umbrella above it. The Burmese used to believe that this spire was in the very middle of the earth.

10. Another fine building is a high lookout tower. From the top of it there is a grand view. On one side I saw a hill covered with temples. At the foot of the hill there were four hundred and fifty of these temples. There must be thousands of them in and near the city.

11. As I drove to my hotel last night I saw a number of boys playing Burmese football. They do not take sides, nor do they try to kick goals. The football is made of basket-work.

12. The boys stand round in a ring, and the game is to keep the ball from touching the ground. The boys pass the ball from one to the other by knocking it up with their heads, arms, hands, legs, or toes. Some of the boys are very clever at this game.

13. Burma has many beautiful rivers and some fine mountains. By the side of the rivers much rice is grown. Away in the north there are grand forests filled with wild animals. Tigers are often shot within twenty miles of the old king's palace.

14. Now I have filled my paper, and I must bring this letter to an end. I hope you are all well and happy. I am leaving Burma tomorrow.—Best love to you all. FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—A week ago I landed in the beautiful island of Ceylon. It lies to the south of India. Get mother to show it to you on the globe.

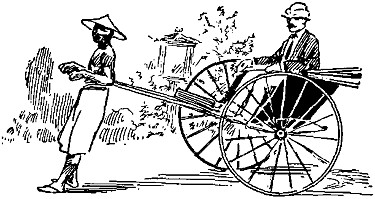

2. I am still under the British flag, the Union Jack. I can see it waving from the top of a big building. The people of Ceylon are proud to call themselves British.

3. I have just been for a ride through the streets of the chief town. I rode in a rickshaw—that is, a kind of large baby-carriage drawn by a man. My rickshaw had rubber on its wheels, so we went along very smoothly and quickly.

4. Some of the carts are drawn by little bullocks that trot along as fast as a pony. I often meet carts with a high cover of thatch. These carts carry the tea, which grows on the hills, down to the ships in the harbour.

5. Some of the men of Ceylon wear tortoise-shell combs in their hair. They are very proud of these combs, and some of them are very handsome.

6. The children of Ceylon seem very happy. They are pretty and clean, and always obey their parents. Many of them learn to speak and read English. They love dancing and singing, and they never quarrel.

Ceylon Girls Playing the

Tom-Tom.

(From the picture by E.A. Hornel. By permission of

the Corporation of Manchester.)

7. By the next ship home I am sending mother a chest of tea. The tea grew on the hills of Ceylon. I made a journey to these hills by train. On the way we passed through thick forests, and by the side of beautiful rivers.

8. Ceylon is very rich in plants and trees. The cocoanut palm grows almost everywhere. On one of the rivers I saw a raft of cocoanuts. A man swam behind it and pushed it along.

9. With this letter I send you a picture of a tea-garden. Notice the men and women plucking the leaf. Many of them come from the south of India. Look at the white planter. He comes, as you know, from our own country.

IN A CEYLON TEA PLANTATION.

10. In the middle of Ceylon there are many high mountains. The highest is called Adam's Peak. It stands like a great wedge high above the other hills.

11. The people of Ceylon believe that it is a holy mountain. They say that once upon a time Buddha climbed to the top of this mountain. To prove that he did so they show you his footprint. It is more than five feet long!

12. A little temple has been built over the footprint. Men, women, and children climb the mountain, to lay little gifts before the footprint, and to strew sweet flowers about it. When this is done, the children kneel down and ask their parents to bless them.

13. To-morrow I leave Ceylon on a long voyage to China. You will not hear from me for several weeks. I hope you are all well, and that you are still good children.—I remain, your loving Father.

A Chinese Street.

(From the picture by T. Hodgson Liddell,

R.B.A.)

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—Three weeks have gone by since I last wrote to you. I have made my voyage safely, and I am now in a great city of China called Canton.

2. Ask mother to show you China on the globe. You see at once that it is a vast country. It is larger than the whole of Europe. One-fourth of all the people in the world live in China.

3. All round this city of Canton there is a high wall. From the wall the city seems to be a beautiful place. When, however, you enter it, you soon find that it is dirty and full of foul smells.

4. The streets are very narrow, and are always crowded with people. Many of them are roofed in to keep them cool. Most of them are so narrow that no carriage can pass along them. People who wish to ride must be carried in a kind of box on the shoulders of two or more men.

5. I am sure you would like to see the signboards that hang down in front of the shops. The strange letters on them are painted in gold and in bright colours. They look very gay indeed.

6. The shops sell all sorts of things—silk, books, drugs, flowers, china, and birds. Some of the shops only sell gold and silver paper. The Chinese burn this paper at the graves of their friends. When they do this they think that they are sending money for their dead friends to spend in the other world.

7. Many things are also sold in the streets. The street traders carry a bamboo pole across the shoulder. From the ends of this pole they sling the baskets in which they carry their wares. Many workmen ply their trades in the open street, and you are sure to see quack doctors, letter-writers, and money-changers.

8. The Chinese do in the open street many things which we do inside our houses. A Chinaman likes to eat his meals where every one can see him.

9. Sometimes he will sit in front of his house and wash his feet. Yesterday I saw a man having his tooth drawn out of doors. A crowd stood round him, watching to see how it was done.

10. How should you like to go for a ride in a wheelbarrow? In China the wheelbarrow is often used for carrying people or goods from place to place. It has a large wheel in the middle. Round the wheel there is a platform for people or goods.

11. A broad river runs through the city. It is crowded with boats, in which live many thousands of people. Many of these people never go ashore at all.

12. Over the sterns of the boats there are long baskets. These are the backyards of the floating city. Hens, ducks, geese, and sometimes pigs, are kept in these baskets.

13. The little boys who live on the boats have a log of wood fastened to their waists. This keeps them afloat if they fall overboard. The little girls have no such lifebelts. In China nobody troubles about the girls.

14. Nearly all the boats have an eye painted on their bows. Perhaps this seems strange to you. The Chinese, however, say,—

"S'pose no got eye, no can see;

S'pose no can see, no can walkee"

1. Chinese fathers and mothers are very glad when their children are boys. In China the boys are much petted. Their mothers give way to them, and let them do as they please.

2. Girls, however, are not welcome. Sometimes they are called "Not-wanted" or "Ought-to-have-been-a-boy."

3. A Chinese boy has always two names, sometimes four. He has one name when he is a child, and another when he goes to school. He has a third name when he begins to earn money. When he dies he has a fourth name.

4. Chinese boys are very fond of flying kites, which are shaped like fish or butterflies or dragons. Old gentlemen are just as fond of kite-flying as boys.

5. In China you will often see boys playing hopscotch or spinning peg-tops. They also play shuttlecock, but they have no battledore. They kick the shuttlecock with the sides of their feet.

6. Chinese boys love to set off fireworks, such as crackers, wheels, and rockets. If the fireworks make a loud noise, so much the better.

7. Chinese children are taught to show very great respect to their parents. They all bow and kneel to their fathers and mothers. A boy who is not kind and good to his parents is thought to be a wicked wretch.

8. A few days ago I went to see a Chinese school. The boys sit on stools at tiny tables. In front of them they have a stone slab, a stick of Chinese ink, and some brushes with which they write.

9. There is always a great din in a Chinese schoolroom. The boys shout at the top of their voices. If they do not make a noise, the teacher thinks that they are not learning.

10. When a boy knows his lesson he goes up to his master to say it. He turns his back to his master, and does not face him as you do.

11. A Chinese boy becomes a man at sixteen years of age. He chooses his work in life when he is quite a baby. Let me tell you how he does it.

12. When he is one year old he is seated in the middle of such things as money, books, and pens. Then the parents watch him to see what he will play with.

13. If he takes up the money, they say that he must be a trader or a banker. If he takes up a book or a pen, they say that he must be a writer or a teacher or a scholar.

1. Chinese men shave their heads, all but a small patch of hair. This is allowed to grow very long, and is plaited into a pigtail. I have seen Chinamen with coloured ribbons woven into their pigtails.

2. When men are at work they twine their pigtails round their heads. When they wish to show respect to any person they let down their pigtails. A man who has a long, thick pigtail is very proud of it.

3. Sometimes men who are sent to prison have their pigtails cut off. This is thought to be a great disgrace. When they leave prison they buy false pigtails to wear.

4. When Chinamen fight they pull each other about by the pigtail. Sometimes a schoolmaster punishes bad boys with his pigtail.

5. Rich women are very proud of their tiny feet. Chinese ladies can wear shoes about four inches long. Fancy mother wearing a doll's shoes!

6. Girls have their feet bound up tightly when they are five years of age. The bandages are made tighter every week, until the foot stops growing. Of course, the poor girls suffer very much. The Chinese have a saying: "Every pair of bound feet costs a bath of tears."

7. When the girls grow up they cannot walk. They can only totter along, and they have to lean on the arm of a maid to keep themselves from falling.

8. I am glad to say that many parents do not now bind the feet of their girls. They have learnt that it is both wicked and foolish to do so. At one school in China all the girls have their feet unbound. They skip and play about almost as well as Kate and May.

9. You and I think that only dirty, untidy people let their nails grow long. Rich people in China never cut their nails. They let them grow so long that they have to wear shields to keep them from being broken.

10. The dress of a Chinaman is very simple. He wears trousers and several cotton or silk tunics. The outside tunic has very long, wide sleeves; these are used as pockets.

11. The trousers are loose, and are covered up to the knee by white stockings. When a Chinaman is in full dress he wears a long gown. The Chinese boy wears the same kind of clothes as his father. Every man, woman, and child carries a fan.

12. Chinese boots are made of cloth or satin, never of leather. The soles are made of rags or paper. We blacken the uppers of our boots. Chinamen whiten the soles of theirs.

13. Now I must end this letter. When I come home you must ask me to tell you about the rice fields and the silk farms and the Great Wall. I have a hundred more things to tell you about this wonderful land.—Your loving FATHER.

A Rich Chinaman's House.

(From the photograph by J. Thomson,

F.R.G.S.)

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—Once more I have made a long sea voyage, and once more I am safely on shore. I am now in Japan.

2. The Japs live on islands, just as we do. They are brave and clever and busy, and they have many fine warships. Because of all these things they are sometimes called the Britons of the Far East.

3. Most of the people in the East are very backward. They have stood still while the people of the West have gone forward. Not so the Japs. They have learnt everything that the West can teach them. You will see in Japan all the things on which we pride ourselves.

4. The Japs are first-rate sailors. Some of their captains learnt to be sailors on board our warships. They are also fine soldiers. You know that not many years ago they beat the Russians both by land and by sea.

5. I like the Japs better than any other people that I have met in the East. Many of them still wear the dress of olden days, and keep to their simple and pretty ways. Their country is beautiful, and they love beautiful things.

6. They are very fond indeed of flowers, which they grow very well. Their gardens are lovely. When the flowers are in bloom the Japs troop in thousands to see them. It is pretty to watch the delight of fathers and mothers and children at the form, colour, and scent of the flowers.

7. The Japs are very clever workmen. I have often stood and watched them at work. They always try to beat their own best. Good work of any kind gives them joy; bad work gives them pain.

8. I have bought Jap fans for Kate and May. On these fans there are pictures of a snow-clad mountain shaped like a sugar loaf. There is no more beautiful mountain in all the world.

9. This mountain began as a hole in the ground. Melted rocks boiled up out of the hole and built up the mountain. In time the rocks grew cool and hard. Some Japs believe that it was formed in a single night!

10. Steam still comes out of a crack in the side of the mountain. This shows that any day melted rocks may boil forth again. About two hundred years ago the mountain threw out so much ash that it covered a town sixty miles away.

11. Sometimes the earth shakes and opens in great cracks. When the earth "quakes" houses tumble down, and the tops of tall trees snap off. Very often lives are lost.

1. When a Jap boy is born there is great joy in his home. His mother's friends all come to see him. They bring him presents, such as toys, dried fish, and eggs.

2. Very early in his life the little Jap baby is strapped on to his sister's back. He goes with her wherever she goes. If the weather is cold, the little girl covers him with her coat. When the sun is hot she shelters him with her sunshade.

3. When she plays she jumps and skips and runs about, and all the time baby's little head jerks to and fro. He does not mind; he is quite happy. You never hear a Jap baby cry.

4. When a boy is about three years of age he learns to walk. He soon finds his feet, and runs about on high wooden clogs.

5. Jap boys are fond of pets and games. Wherever a boy goes he carries with him a long pole. With this he makes flying leaps and does many clever tricks.

6. Every boy in Japan wishes to be either a soldier or a sailor when he grows up. Even tiny little mites play with flags and drums and little guns. When the boys are older they are taught to be brave, and to die if need be for their country.

7. The great day of the year for Jap boys is the fifth day of the fifth month. On this day the Feast of Flags is held. Over each house where there is a boy you see big paper fish floating in the air.

8. The shops are then full of toys. Most of the toys are soldiers, and sometimes they are like the soldiers of olden days. Some are on foot, and some are on horseback; some are generals, and some are drummers.

The Toy Seller.

(From the water-colour painting by H.E.

Tidmarsh.)

9. The boys love to play at war. You can always make Jap boys happy by giving them a toy army to play with.

10. The greatest day of the year for the girls is the Feast of Dolls. On this day the girls give doll parties to their little friends. All the dolls, however old, are brought out and dressed up in fine new clothes. The Feast of Dolls is a time of great fun and laughter.

11. Jap children now play many of our games. They are very fond of "prisoner's base," "fox and geese," and "tag." The boys love kite-flying.

12. Sometimes they put glass on the strings of their kites, and with it try to cut the strings of other boys' kites. They are very clever at this game, and there is great laughter when a string is cut.

13. In the house, during the day, girls like to blow soap bubbles. At dusk they are fond of hunting fire-flies, and driving them to and fro with fans.

14. In the summer they catch grasshoppers, and keep them in small bamboo cages. They say that the chirping of the grasshoppers brings them good luck.

15. All Japs are polite—even boys. When a boy goes to the house of a friend he squats on his heels. Then he places his hands on the floor, and bows until his forehead touches his toes. This he does again and again, and all the time he speaks very politely.

16. Jap children are taught to be very kind and helpful to their elders, and to the poor and the weak. Yesterday I saw a little girl run from her mother to take the hand of a blind man and lead him across the street.

17. Now, my dears, I must end this letter. To-morrow I start on my homeward way. I shall sail across the ocean to the great land of America. I hope you are all well, good, and happy. Your loving FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—Look at the globe in my room and find Japan. Then find America. You will see that a broad ocean lies between them. It is called the Pacific Ocean. I have crossed this ocean, and I am now in the great country of Canada.

2. I am sure that you cannot guess where I am writing this letter. I am writing it in the train. I have already been three days in the train, and I am only half-way across Canada.

3. I am glad to say that I am once more under the Union Jack. The whole land of Canada is British, from sea to sea. Our flag floats above every city.

4. The first part of my journey pleased me most. The train ran through a beautiful country, filled with splendid trees. Some of them are as high as a church tower, and have trunks many yards round. There are no finer trees in all the world.

5. Later in the day our train ran by the side of a rushing river, which was deep down in a narrow valley between the mountains.

6. In this river there are millions of salmon. I saw men catching them. You will see tins of salmon from this river in most of the grocers' shops at home.

7. As the train ran on, the mountains rose higher and higher, until their tops were covered with snow. We then began to cross the great Rocky Mountains. Up and up the train climbed, until the rails reached their highest point.

8. Then we began to descend. We ran through dark clefts in the rocks, along the edges of steep cliffs, across rivers, and by the side of lakes. High above us were the snowy mountain tops. It was all very grand and very beautiful.

Harvest-Time in Canada.

(From the picture by Cyrus Cuneo, R.I. By kind

permission of the C.P.R. Co.)

9. At last we left the mountains behind us and reached the plains. We are now speeding over these plains. The country is as flat as the palm of your hand. Here and there, far apart, I can see farm-houses. On these plains the best wheat in the world is grown.

10. In winter the whole land is covered deep with snow, and the rivers are frozen over. In April winter gives place to spring. Then the snow melts, and the ice on the rivers breaks up.

11. No sooner has the snow gone than the wheat begins to spring up. The wheat grows very fast and ripens very quickly. Much of it is sent to Britain. Very likely the loaf which you ate for breakfast this morning was made of wheat which grew on the plains of Canada.

12. In other parts of Canada there are forests which cover thousands of miles of country. The trees in these forests are cut down, and are made into planks which are sent to all parts of the world.

13. The trees are felled during winter. Their trunks are piled up by the side of a river. When the thaw comes they are thrown into the water. Men follow them and push them back into the water if they drift ashore.

14. The stream carries the logs down to the sawmills, where they are cut up into planks. Love to all. FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—I am staying for a few days with a friend who has a farm on the plains. His house is five miles from the railway.

2. My friend met me at the station with a motor car, and drove me over rough roads between huge fields. There are no hedges in this part of the country. The fields are divided from each other by fences.

3. This farm is much larger than any farm which you have seen in England. The house is built of wood. All round it is a pretty garden. Not far away are the stables and the barns.

4. I am sure you would like to hear something about the farmer's children. There are three of them—a girl and two boys. The girl is the youngest, and she is about eight years of age.

5. All the children make themselves very useful in the house. Servants are hard to get in Canada, so people must learn to help themselves. The boys clean the boots and chop wood. The girls think nothing of helping to scrub the floors.

6. After breakfast the children trudge off to school, which is three miles away. They take their lunch with them. When they return in the evening they have many odd jobs to do.

7. In the playground of their school you will see many young trees growing. There are very few trees on the plains, and far more are needed.

8. On one day in each year the children make holiday, and plant trees in the school grounds. The teacher tells them that when they grow up they must plant trees on their farms.

9. Harvest is the busiest time of the year. Then the children rise at half-past four, and work all day long in the fields. Every one who can work at all must do so at harvest time.

10. There is also plenty of work to be done in the autumn. Everything needed in the house must be brought in before the snow begins to fall.

11. Winter is the real holiday time. No work can then be done on the land. The rivers and lakes are frozen, and everywhere there is plenty of skating. The wheels are taken off the carriages, and runners are put on instead. Horses draw them very swiftly over the frozen snow.

BOYS OF CANADA IN WINTER.

12. Look at the picture post-card which I send you with this letter. It shows you how Canadian boys are dressed in winter. On the ground you see a pair of snow-shoes. The boys can travel very quickly on these snow-shoes without sinking into the snow.

13. In the picture you also see a toboggan. It is a small sledge. The boy drags his toboggan up to the top of a hill. He seats himself on it and pushes off. Away he goes over the frozen snow like an arrow from a bow. It is splendid fun.

14. Those boys and girls whose homes are in towns live very much as you do. They go to school, and they play in the streets and parks. When summer comes many of them go to the seaside or to the lakeside for a holiday.

15. Sometimes a whole family goes camping in the woods. They then live in tents or in little huts by the side of a river or a lake. What happy times the children have! They go fishing, they bathe, and they dart to and fro in canoes.

16. Most of the young folks of Canada are strong and healthy. They are happy and bright, and they are not afraid of work. No children are more useful to their parents than the boys and girls of Canada.

Red Men and White Men.

(From the picture by Cyrus Cuneo, R.I. By kind

permission of the C.P.R. Co.)

1. Tom will not forgive me unless I tell you something about the Red men of America. He has often asked me about the picture of Red men which is in my room at home.

2. In the old days, before white men settled in America, the Red men were masters of the land. They were tall and strong, and their skin was of a dark copper colour. Their eyes were jet black, and their hair was long and straight.

3. They wore very little clothing, even though the winters in North America are very cold. From the time when they were babies they were trained to bear heat and cold, hunger, thirst, and pain without grumbling.

4. When the white men landed in America, the villages of the Red men were to be found all over the country. Each of these villages was the home of a tribe. The houses were tents made of skin or huts made of wood.

5. The women or squaws did all the hard work. They planted and tilled the fields, cooked the food, and made the clothes. The babies were put into little bark cradles, which were sometimes hung from the branches of trees, and were rocked to and fro by the wind.

6. The Red men were nearly always at war, either amongst themselves or against the white men. In battle they were very crafty and skilful. Those who fell into their hands were sometimes treated very cruelly.

7. Before the Red men went on the "warpath" they painted their faces, so as to frighten their foes. Then they took up their bows and hatchets, and, following their leader, strode silently away.

8. The Red men did not care to fight in the open. They always tried to catch their foes asleep or to take them by surprise.

9. In those days the land was full of deer and other wild animals. On the great plains where the wheat now grows huge herds of bison used to feed.

10. The Red men hunted the bison on their swift little ponies. When they were close to the animals they shot at them with arrows. If the arrows missed their mark, the Red men killed the bison with their knives.

11. When the white men came they hunted the bison with guns, and soon killed them off. Only a few bisons remain, and these are now kept in parks.

12. There are not many Red men left in North America. Most of them have died off. Many of those who now remain have given up their old way of living.

Amongst the Eskimos.

1. Here is another picture for you. Look at it carefully. It shows you the people who live in the far north of Canada. They are called Eskimos.

2. In the upper part of the picture you see a man on a sledge. He is dressed in furs, and has fur gloves on his hands. His head and ears are covered with a hood. In the far north of Canada the cold is so bitter in winter that men's hands and ears would be frost-bitten if they were not kept warm in this way.

3. In winter the sea and the land are thickly frozen over. The whole country is covered with ice and snow. The Eskimo has to travel over the ice to get from place to place. He uses a sledge drawn by dogs. There is a team of dogs in the upper part of the picture.

4. Sometimes the sledge is overturned, and the men and dogs are thrown into deep, wide cracks in the ice. Sometimes fierce storms arise, and men and dogs perish together. Sometimes food runs short, and they die of hunger.

5. In the middle part of the picture you see a tent. The Eskimos can only live in tents during the short summers; during the long dark winters they live in huts. The walls are made of stones and sods. The roof is of wood which has drifted to their shores. You must remember that no trees will grow in these very cold lands.

6. Some Eskimos make their winter houses of blocks of snow, with sheets of ice for the windows. Perhaps you shiver at the thought of living in a snow house, but you need not do so.

7. Really, a snow house is quite a snug home. The snow keeps in the heat of the house, just as a blanket keeps in the heat of your body. Perhaps you know that it is the blanket of snow spread over the ground in winter which keeps the roots of the plants from being frozen.

8. When summer comes, the snow and ice melt along the edge of the sea. Then the Eskimo leaves his winter quarters for the seashore.

9. The sea-shores of these very cold lands abound in bears, seals, foxes, and other wild animals. The sea is full of fish, and millions of gulls, geese, and other birds fly north for the summer.

10. When a boy is ten years of age his father gives him a bow and arrows and a canoe. Then he thinks himself a man indeed. In the lower part of the picture you see a man in an Eskimo canoe. He is going to hunt seals and small whales.

11. Now I must bring this long letter to a close. I shall write you one more before I start for home. I am eager to see you all again.—Your loving FATHER.

1. MY DEAR CHILDREN,—This is the last letter which I shall write to you from abroad. I hope to sail for home in a week's time. I shall send you a telegram to tell you when I shall arrive. You must all come to the station to meet me.

2. Look at the globe and find North America. The northern half is called Canada, and the southern half is called the United States. I am now in New York, the largest city of the United States.

3. The people of the United States speak English. The forefathers of many of them came from our islands. But the United States do not belong to Britain. Their flag is not the Union Jack, but the Stars and Stripes.

4. This morning at breakfast a black man waited upon me. His skin was very dark, his lips were thick, and his hair was short and curly.

5. Are you not surprised to hear that there are black men in America? There are thousands of them in New York. In the southern part of the United States there are more black men than white men.

6. Most of the black men live in the hot part of the United States, where cotton and sugar are grown. White people cannot work in the cotton or sugar fields, because the sun is too hot for them.

7. The black people who live in the United States were born in America. They have never known any other land. America, however, is not their real home. They really belong to Africa.

8. How is it that we now find them in America? When the white men of America began to grow cotton and sugar, they needed black men to work in the fields. Men called "slavers" went to Africa in ships. They landed and pushed inland. When they came to villages they seized the people and drove them off to the ships.

9. The poor blacks, who were thus dragged from their home and kindred, were thrust into the holds of ships and carried to America. Sometimes they suffered much on the voyage. The weakest of them died, and were thrown overboard.

10. When they reached America they were sold to the cotton-growers and sugar-growers, who carried them off to work in the fields. Sometimes they were kindly treated; sometimes they were flogged to make them work. But whether kindly or cruelly treated, they were no longer men and women, but slaves.

11. This went on for many years. At last some kind-hearted men in the northern states said, "It is wicked to own slaves. All the slaves in America shall be set free."

12. The farmers of the south were very angry when they heard this, and said that they would not free their slaves. Then a fierce war broke out. The North beat the South, and when the war came to an end all the slaves in America were set free.

13. The blacks still work in the cotton and sugar and tobacco fields; but they now work for wages, just as I do. They are free to come and go as they please.

14. The darkies are very merry and full of fun. When their work is over they love to sing and dance to the music of the banjo. Some of their songs are very pretty. I will sing some of them to you when I come home. Good-bye, dears. I shall soon be with you now.—Your loving FATHER.

1. The telegram came soon after breakfast. Father was coming home that very day. We were so delighted that we sang and danced and clapped our hands, just like the darkies.

2. Mother was very busy. "You must all come and help me," she said. "The house must be made beautiful for father's return."

3. May and I worked with mother, but the day passed very slowly. Father's train was to arrive at six o'clock. By half-past five we were all at the station waiting for him.

4. At last the train steamed in, and out jumped father. Oh, how we hugged and kissed him! Father was well, and he looked very brown.

5. I sat next to him in the cab. He told us that his ship had only reached Liverpool that morning. He had taken the first train for home, because he wished to see us so much.

6. After tea he opened one of his boxes. "I have brought each of you a present," he said. "Sit down, and I will show you some pretty things."

7. Mother's present was a dress from India. It had gold and beetles' wings on it. They were a lovely shiny green, just like jewels.

8. My present was a necklace of beautiful blue stones. May's was a dolly, dressed just like an Indian lady. Tom's was a kite from Japan. It was shaped just like a dragon. Of course, we were all delighted with our gifts.

9. Then father told us many things about his travels. "I have been right round the world," he said. "I sailed to the East, and I went on and on until I returned to the place from which I set out."

"I know," cried Tom. "I have followed you all round the world on the globe."

10. May was sitting on father's knee. "Dad," she said, "I suppose you are the very first man who has ever been right round the world." "Of course he is," said Tom.

11. Father laughed. "No, my dear," he replied; "thousands of men had been round the world before I was born."

12. "I'm so sorry," said May. "I did so want to tell the girls at school that my father was the very first man who ever went round the world."

1. The father travelled by train. In what other ways might he have travelled? Which is the fastest way? Which is the slowest?

2. What power drives the train? What other work does this power do?

3. Look carefully at the first picture in this book. Describe it.

4. Learn: A globe is a small model of the earth. Of what shape is the earth? Of what shape are the sun, moon, and stars?

1. The name of the town on the seashore (par. 2) is Dover. Turn to the picture on page 11 and describe the cliffs of Dover as seen from the sea.

2. The distance between Dover and Calais is only twenty-one miles. Learn: A narrow passage of water joining two seas is called a strait. The word strait means "narrow." This strait is called the Strait of Dover.

3. Model the Strait of Dover in clay or plasticine. Suppose the water between England and France were to dry up, what would the strait be then? Write out and learn: A valley is a hollow between hills or mountains.

1. The river which runs through Paris is called the Seine. The river which runs through London is called the Thames. Learn: A river is a large stream of fresh water flowing across the land to join another river, a lake, or the sea.

2. Look carefully at the picture on page 14 and describe it.

3. Compare French boys with English boys. Compare French girls with English girls.

1. Look carefully at the picture on page 18 and describe it.

2. Copy this little drawing of the silkworm and the mulberry leaf.

3. Why do flowers bloom earlier in the south of France than in England?

4. Describe the picture on page 20.