The infant Samboe, thus bereaved of his suffering mother, was yet too young to feel

the full magnitude of his loss; yet his little heart experienced emotions he had no

power to utter, when he was told she would [111]never more awake to his call, nor could he feel happy, when, with expressions of joy, he saw the negroes of the plantation remove his “silent

mother” to the burial ground, with every demonstration of joy. (Note R.)

An ever kind Providence has, however, made the griefs of children to be transient;

and Samboe, the favourite of Mrs. Delaney, from his sweetness of disposition, great

activity, and early intelligence, would probably have presented a pleasing exception

to the unhappy lot of his enslaved countrymen—might justly have enjoyed the title

of the happy negro—had his benefactress been spared to bless the sable dependants on her kindness. But

life, at all times and in all situations transient and uncertain, may be said to be

peculiarly so in the West Indies; the progress of disease being so rapid, and the

excitements to it so many. That dreadful visitation, the yellow fever, broke out in

the district of the Delaney plantation: numberless were the victims to the “pestilence

that walketh in noon-day;” and among them were Mr. Delaney and his amiable wife.

[112]

Those who were capable of appreciating their worth, who had felt their benevolence,

had enjoyed the privileges they allowed, and knew how rarely they were found in the

plantations, mourned them with unfeigned sorrow, their loss closing up the avenues

of consolation and of hope; and those too young to feel how much they were deprived

of, were quickly made sensible of a change from a system of Christian love and benevolence,

to that built upon the mere hope of worldly gain. As it is not the custom in the English

colonies, as in the French, for the negroes to be attached to the plantation, those

of the Delaney estate were, upon the sale of it, dispersed amongst different purchasers;

and the infant Samboe became the property of a cruel mercenary, who employed the poor

child to wait upon him, when indulging in all the luxurious ease of an occidental

despot. By those who have seen the various caprices of a temper altogether uncontrouled,

the whims of a mind destitute of cultivation and obstinate in ignorance, the cruelty

of a disposition formed by the possession [113]of a precarious power over helpless individuals; by those, and those only, will the

various species of suffering to which the innocent child was subjected be understood;

and the terrors which were produced by the horrid imprecations, the unmanly abuse,

and vulgar epithets of this brutal master, upon the gentle and timid character of

the poor little Samboe. It was then he began to feel the loss, and to pine for the

tenderness of his mother and his benefactress; and there is little doubt but he would

have soon followed them to the tomb, had not an incident occurred, that emancipated

him from the tyrannical controul by which he so acutely suffered. One day, while attending

his master at breakfast, just as he handed the coffee his foot slipped, and it was

thrown over a beautiful cimar, which the luxurious planter highly valued, as the gift

of a lady to whom he was partial. He rose in haste and in anger, and aiming a blow

at the now kneeling boy, missed the blow, and fell himself to the ground, striking

his head by the fall against the edge of a sofa. Seeing him suddenly [114]fall, some attendants in waiting rushed to his assistance, but in vain: the blow had

been fatal, he had fallen to rise no more on earth! Happy was it for Samboe that there

were witnesses, white witnesses of the scene, who could exonerate him from all intentional connexion with,

or wilful provocation to the catastrophe. The alarm, however, of the unoffending child

was distressing: the countenance of the planter at all times bore evidence of his

ill-regulated mind and indurated heart, and the awful hand of death fixed them in

an expression the most horrid. With little idea of such sudden death, the poor child

thought he was but in a violent passion, and, in the most piteous accents, clasping

his hands together, besought “massa to forgive poor Samboe, who would not break cup

any more, would not spoil dress any more.” But his supplication was alike unheeded

by master and attendants, except by one, who kicking him as he passed, said: “Get

out of the way, ye little whining dog, or I’ll make ye.” Samboe crept from the apartment,

and crouching under some furniture, [115]felt all the bitterness of a life of slavery, of which nature, in its first fresh

feelings, can be capable. Happily again for the infant captive, the wife of the planter

could not bear to retain in her service the innocent cause of her husband’s death;

at least, secretly rejoicing at her own emancipation from his arbitrary disposition,

she affected so to say: consequently, she expressed her wish of selling him to the

manager of a neighbouring plantation, but as her recent loss rendered it impossible

for her to have a personal interview, she thus communicated her wish by note to this

person: “Unable to bear the sight of the young author of the death of the best and

tenderest of husbands, Mrs. Williamson requests the favour of Mr. Martin to take charge

of, and dispose of him, in any way he may judge most conducive to her interest, and

to employ the proceeds in the purchase of a more effective, that is, laborious slave.

Mrs. W. relies on the known kindness of Mr. M. to render this service to the disconsolate

widow of his late friend.” My young readers will doubtless [116]be shocked, that Mrs. Williamson should thus profess grief for the loss of a man she

married for his wealth, without either esteeming or loving him; but it is no fancied

picture, and is presented to show, that, unless the heart is continually watched,

and the mind sedulously cultivated, in situations favourable to indolence and self-indulgence,

the moral feelings quickly become blunted, and the individual can easily, and without

any self-reproach, assume any sentiments and any line of conduct which best suits

the whim or caprice of the moment; and she hated the little Samboe, because she once

overheard him, in a moment of unusual gaiety, telling a circle of slaves what merry

dances they had at Delaney, when dear Missy Delaney danced with poor Samboe. Upon

such trifles will envy condescend to feed its insatiate appetite. Good, however, to

Samboe, was educed from all this evil. Mr. Martin was the respectable and humane manager

of the Moreton estate; (see “Twilight Hours Improved,” page 85;) subjected to his superintendence during the minority [117]of Mr. Frederick Moreton, by the will of his deceased father; and whose humane treatment

of his negroes had excited the displeasure of the young man’s guardian, Mr. Penryn,

who firmly believed the African race created only to become the slaves of Europeans.

Mr. Martin lost no time in complying with the request of his fair neighbour. He well

remembered frequently having seen the little Samboe in attendance upon his imperious

master, and never failed to admire his extreme docility, mildness, and intelligence;

and he looked upon the circumstance of Mrs. Williamson’s desire to sell him, as very

fortunate, as he had, only a few days previous, received the commission to send to

England a negro boy for his young master.

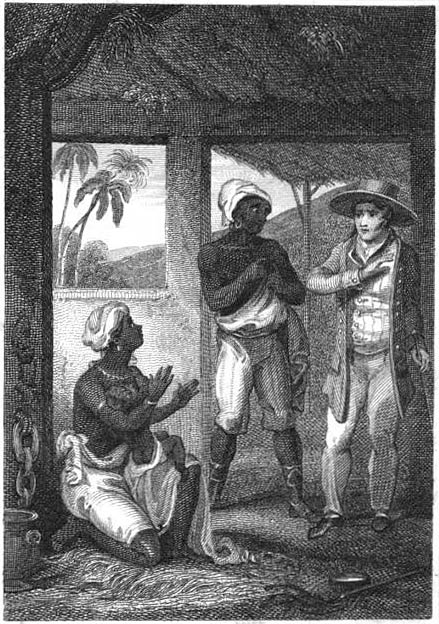

The purchase was soon made, and Samboe was once more under the roof of an indulgent

master. Every attention was given, in order to establish his health, and improve his

personal appearance, that he might credit the choice of his purchaser, and please

the young eye of his future master. He only remained at Jamaica to effect these [118]purposes, when he was consigned to the care of the captain of an English West Indiaman,

with instructions to have him safely conveyed to Mr. Penryn’s, Portman Square.

Samboe evinced the greatest reluctance to go on board; he clung to Mr. Martin, who

himself conducted him, and trembled violently, declaring he could not go into great

ship, or on great wide sea. No one could account for this extraordinary reluctance

and evident terror; for they knew not that the young heart of the little negro was

throbbing with recollections for which he had no name, and which he had no power to

express. It is true, they were vague, like the confused remembrance of a troubled

dream, but they were powerful; and it was with the utmost difficulty Mr. Martin soothed

him, by gentleness, promises, and assurances; and, after all, was obliged to leave

him, when he had cried himself to sleep upon a coil of rope on the deck, no one being

able to prevail upon him to go below, and Mr. Martin positively forbidding coercion.

The grief and terror of the poor boy were [119]renewed, when he discovered he had been left by Mr Martin; but a series of kind treatment,

and many little indulgences granted him, after a while reconciled him to his new situation;

while his simplicity and quickness greatly endeared him to the sailors, with whom

he became quite a pet. The voyage passed in this manner without any particular occurrence;

and Samboe was introduced, one evening, to the dining room of Mr. Penryn, filled with

elegant company.

Had he been one of the wonders of the world, he probably would not have excited more

attention, or elicited more remarks. The ladies admired his eyes and his teeth; the

gentlemen enquired if he was a Molembo, or from the Kroo country, and began an animated

debate on slavery, and the slave-trade. Each lady gave her opinion of the most becoming

dress to contrast with the jet black of his skin. One asked him if was not glad to

come to England; another enquired if he was sorry to leave Africa; a third enquired

if they flogged him at the plantation; while a fourth, by way of compliment [120]to the lady of the house, observed, he was a happy black boy, to have such a charming

mistress. To all these remarks the poor child could give no reply; nor, it would seem,

was it expected; and, much to his joy, he was dismissed to the care of the groom,

until his apartment and employment about the person of his young master could be arranged.

The groom, however, was highly indignant that a vile neger boy should be committed to his care: “Did they fancy he would let a black get between

his sheets? No, indeed; there was the hay-loft, the stable-boy should pull him a truss

of straw in the corner there: surely that would be a better bed than most negers got.

Sleep with me, indeed; no, I’d lose my place first, and tis’n’t a bad one, neither. Had they told me to take Cæsar the house-dog, or Neptune the Newfoundlander, I should

not have so much have minded; but a neger boy! surely my master was half-seas over

to think of it.” This, and much more of the same refined objection, passed in the

kitchen of —— Penryn, esq. [121]and, according to the groom’s kind arrangement, Samboe was indulged with some clean

straw in the stable-loft.

The children of oppression and calamity quickly sympathize; a kindred feeling draws

them together: thus it was with Samboe the African, and Frank the English stable boy.

An orphan from his cradle, and a parish apprentice, Frank had been early subjected

to every oppression—exposed to every temptation; but a certain buoyancy of spirit,

and a persevering ardour of mind, enabled him to rise above the one; and the latter

was rendered less dangerous, by his constant, unremitted love of employment. He was

busily engaged mending his shoes, when his master, the groom, introduced the young

negro to his acquaintance. “There, Frank,” he said, “there is a companion for you,

my lad; take care he don’t touch the horses, and mind he don’t run away. Lock him

up when you come in for your supper: you may offer him some, but I don’t know what

negers eat, I’m sure. Master should have told us that, I think, for I don’t expect

they [122]live as we do. Eh! my lad, do ye mind me?” he added, with a raised voice, as he saw

Frank take the hand of the timid Samboe, and ask him if he was tired. “Oh yes, sir!”

he replied, touching his fur cap, “I will be sure to take care of him.”

Glad to get quit of the restraint which the charge imposed upon him, the groom was

in high good humour with Frank, and promised, if he would attend to his orders, he

would give him a shilling. Astonished at his unwonted generosity, Frank repeated his

assurances; and having made his new companion understand that he desired to make him

comfortable, with the happy facility of children to be so when left to themselves,

they quickly became acquainted. Frank found that negers could eat good bread and fresh meat; that they had no objection to tarts; and that

even a custard, given by the cook as a treat to merry Frank, was equally relished

by the neger boy. After this luxurious repast, during which, if it was not the “feast

of reason and the flow of soul,” there was, most unquestionably, [123]innate benevolence on one side, and genuine gratitude on the other, the new-made friends

sought repose on the same clean truss of straw, and together enjoyed the refreshment

of “nature’s sweet restorer.” Not long, however, after they had thus lain down, Frank

was roused from his yet imperfect slumber, by a slight rustling and a low voice, very

near him. He spoke gently to his new bed-fellow, but received no reply. Frank had

that tincture of superstition which usually attaches to the ignorant and uncultivated;

and the unusual sound, his new situation, and the profound darkness, aided the impression;

while a thought of the little negro became associated with the recollection of several

marvellous ghost-stories he had heard. He ventured, however, (not without considerable

reluctance,) to feel if his sable companion was by his side, and discovered, to his

amazement, that he was not there. The murmur still continued, and Frank, trembling

all over him, made a desperate effort, and called lustily, “Samboe, Samboe!” “Samboe

here,” replied the boy, [124]in a soft and gentle tone; “Samboe here, but wicked boy.”

Frank’s courage returned at the sound of Samboe’s voice clearly pronouncing these

words, although he was at a loss to account for his self-accusation. “Why, what have

you done to be wicked; where are you?” he enquired. Samboe’s imperfect knowledge of

the English language, permitted him not to understand the full import of these questions;

and it was not until Frank, with renewed courage at finding his companion was really

a mortal, contrived to make him understand his repeated enquiry, why he had risen,

and why he called himself wicked? “Because Samboe forgot lesson dear Missy Delaney

teach him. Pray to great God before sleep; pray to great God when eyes open; pray

to good God give food; pray to good God give friends.”

Frank now understood, that Samboe, in the novelty of his situation, and probably from

the effects of a little porter he had taken, had forgotten to offer his simple tribute

of thanks and respect to the omnipotent Creator, [125]which the good Mrs. Delaney had taught him habitually to do; although he was too young

when she died, to admit any further religious instruction, or to understand more than

that a great God, beyond the blue sky, observed all his actions.

Samboe had never, until this night, neglected this lesson; but, with uplifted hands

and bended knee, was accustomed to acknowledge the protection and the support of the

Being he had been taught to regard, as ever beholding, and with unwearied care protecting,

all men. Sleep, however, had not closed his eyes, ere the omission was recollected,

and he had crept out of the straw, to offer his simple orison, the low murmur of which

had so much alarmed his new friend. Having concluded, he returned to his straw couch,

and slept the sleep of innocence, untill awaked by Frank rising to his morning duty

in the stables.

Frank possessed an intelligence of mind, as well as activity of spirit, which required

but opportunities to develope themselves. The incident of Samboe’s forgotten prayer,

[126]impressed his youthful mind. How was it he had never been taught to pray? He had never

seen it practised among those he had been with. He thought people went to church to

pray; yet surely if a black boy thought it right to pray, a white boy ought. Perhaps

it was a custom among them? Yet, such was the innate impression he had, that it was

right and proper, that he felt a species of shame to answer Samboe in the negative,

when he artlessly enquired if he did not pray to great God, to take care of him; he,

too, who knew so many things: for, to Samboe, Frank seemed a miracle of cleverness,

when he described his various employments, and displayed, to his astonished visitor,

the results of his ingenuity, which he did with no little self-complacency.

Samboe seemed now the happiest of human beings. He suffered nothing to pass unnoticed;

asking the reason, the use, the name of every thing he heard, or saw, or touched.

This he contrived to do, either by broken words, gestures, or signs. The new-made

friends thus passed several hours [127]of the morning, before the groom made his appearance; for, although his apartments

were above the stables, he did not often occupy them, finding numerous engagements

more pleasant than attending to his duty.

The only unpleasant circumstance of this morning of delight to Samboe, was its chilliness.

It was one of those which frequently occur in May, as if to reprove the hastiness

of the family of Flora, in putting forth their fair forms; and its asperity was severely

felt by the little African. Frank determined to make him as comfortable as he could;

and having received no orders to the contrary, lighted a fire in the groom’s room,

and invited Samboe to its genial warmth, while he quickly prepared a comfortable mess

of milk-pottage.

They were thus enjoying themselves, when the master of the house appeared, half awake, and storming at Frank for a lazy dog, for not having swept

the stable-door. But he supposed he and the beggarly neger had been idling away their

time together. Frank, who was used to his arbitrary temper, said [128]little; but, making signs for Samboe to return to the loft, he quickly prepared every

thing for his master’s toilet, and proceeded to rectify the omission of not having

swept the door-way. While thus engaged, a servant from the house arrived with an order

to the groom to take the negro-boy to a clothes-shop, and have him neatly clothed,

until a a proper dress could be fixed upon; as he was to have an interview with his

mistress and young master, who neither of them could bear the smell of tar, exhaling

from the filthy things he wore.

This message, delivered in due form to the groom while he was shaving himself, nearly

endangered his cutting his throat, by the resentful agitation it caused, that he should

be appointed to wait upon a neger. It was a degradation which he could not, nor would not submit to. Following, therefore,

the example of his superiors, he delegated the office to his subordinate; and calling

loudly for Frank, as soon as the messenger had left him, he desired him to take the

black he seemed so fond of, to Mr. Draper’s, and get [129]him rigged. “And mind ye, Frank, boy, call at the ’potecaries or ’fumers, and bid

’em pour some musk or lavender, or something sweet over the lad, for missis is very

particular; and as to Master Fred, I shall have him trying how my legs will bear the

exercise of his new hunting-whip, if I do not please him about this black, who, I

dare say, will not be long before he feels it. But I suppose he has been used to flogging,

so it will be nothing to him.”

Frank, highly pleased with this important commission, called the shivering boy from

the hay-chamber, and in no long time he was completely equipped, in a suit according

to the taste of Frank and the vender: certainly as stiff and ill made as it well could

be; while the effusion of lavender-water was completely accomplished, even till the

poor boy’s eyes became filled with tears, from the potency of the perfume, and every

person he passed on his return, half stopped, at meeting with the unusual odour.

Samboe, however, had yet some hours to become reconciled to his new habiliment; [130]and his friend Frank had so many modes and sources of employment and amusement, that

those hours passed insensibly away. At length, about four o’clock, the groom again

appeared to conduct him to the house; and when arrived, a footman desired him to follow

him to the apartment of his lady, previously to her taking her morning airing.