The Project Gutenberg EBook of Manners of the Age, by Horace Brown Fyfe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Manners of the Age Author: Horace Brown Fyfe Illustrator: Marchetti Release Date: June 10, 2010 [EBook #32764] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MANNERS OF THE AGE *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction March 1952. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

With everyone gone elsewhere, Earth was perfect for gracious living—only there was nothing gracious about it!

he red tennis robot scooted desperately across the court, its four wide-set wheels squealing. For a moment, Robert's hard-hit passing shot seemed to have scored. Then, at the last instant, the robot whipped around its single racket-equipped arm. Robert sprawled headlong in a futile lunge at the return.

"Game and set to Red Three," announced the referee box from its high station above the net.

"Ah, shut up!" growled Robert, and flung down his racket for one of the white serving robots to retrieve.

"Yes, Robert," agreed the voice. "Will Robert continue to play?" Interpreting the man's savage mumble as a negative, it told his opponent, "Return to your stall, Red Three!"

Robert strode off wordlessly toward the house. Reaching the hundred-foot-square swimming pool, he hesitated uncertainly.

"Weather's so damned hot," he muttered. "Why didn't the old-time scientists find out how to do something about that while there were still enough people on Earth to manage it?"

He stripped off his damp clothing and dropped it on the "beach" of white sand. Behind him sounded the steps of a humanoid serving robot, hastening to pick it up. Robert plunged deep into the cooling water and let himself float lazily to the surface.

Maybe they did, he thought. I could send a robot over to the old city library for information. Still, actually doing anything would probably take the resources of a good many persons—and it isn't so easy to find people now that Earth is practically deserted.

He rolled sideward for a breath and began to swim slowly for the opposite side of the pool, reflecting upon the curious culture of the planet. Although he had accepted this all his life, it really was remarkable how the original home of the human race had been forsaken for fresher worlds among the stars. Or was it more remarkable that a few individuals had asserted their independence by remaining?

Robert was aware that the decision involved few difficulties, considering the wealth of robots and other automatic machines. He regretted knowing so few humans, though they were really not necessary. If not for his hobby of televising, he would probably not know any at all.

"Wonder how far past the old city I'd have to go to meet someone in person," he murmured as he pulled himself from the pool. "Maybe I ought to try accepting that televised invitation of the other night."

everal dark usuform robots were smoothing the sand on this beach under the direction of a blue humanoid supervisor. Watching them idly, Robert estimated that it must be ten years since he had seen another human face to face. His parents were dim memories. He got along very well, however, with robots to serve him or to obtain occasional information from the automatic scanners of the city library that had long ago been equipped to serve such a purpose.

"Much better than things were in the old days," he told himself as he crossed the lawn to his sprawling white mansion. "Must have been awful before the population declined. Imagine having people all around you, having to listen to them, see them, and argue to make them do what you wanted!"

The heel of his bare right foot came down heavily on a pebble, and he swore without awareness of the precise meaning of the ancient phrases. He limped into the baths and beckoned a waiting robot as he stretched out on a rubbing table.

"Call Blue One!" he ordered.

The red robot pushed a button on the wall before beginning the massage. In a few moments, the major-domo arrived.

"Did Robert enjoy the tennis?" it inquired politely.

"I did not!" snapped the man. "Red Three won—and by too big a score. Have it geared down a few feet per second."

"Yes, Robert."

"And have the lawn screened again for pebbles!"

As Blue One retired he relaxed, and turned his mind to ideas for filling the evening. He hoped Henry would televise: Robert had news for him.

After a short nap and dinner, he took the elevator to his three-story tower and turned on the television robot. Seating himself in a comfortable armchair, he directed the machine from one channel to another. For some time, there was no answer to his perfunctory call signals, but one of his few acquaintances finally came on.

"Jack here," said a quiet voice that Robert had long suspected of being disguised by a filter microphone.

"I haven't heard you for some weeks," he remarked, eying the swirling colors on the screen.

He disliked Jack for never showing his face, but curiosity as to what lay behind the mechanical image projected by the other's transmitter preserved the acquaintance.

"I was ... busy," said the bodiless voice, with a discreet hint of a chuckle that Robert found chilling.

He wondered what Jack had been up to. He remembered once being favored with a televised view of Jack's favorite sport—a battle between companies of robots designed for the purpose, horribly reminiscent of human conflicts Robert had seen on historical films.

e soon made an excuse to break off and set the robot to scanning Henry's channel. He had something to tell the older man, who lived only about a hundred miles away and was as close to being his friend as was possible in this age of scattered, self-sufficient dwellings.

"I don't mind talking to him," Robert reflected. "At least he doesn't overdo this business of individual privacy."

He thought briefly of the disdainful face—seemingly on a distant station—which had merely examined him for several minutes one night without ever condescending to speak. Recalling his rage at this treatment, Robert wondered how the ancients had managed to get along together when there were so many of them. They must have had some strict code of behavior, he supposed, or they never would have bred so enormous a population.

"I must find out about that someday," he decided. "How did you act, for instance, if you wanted to play tennis but someone else just refused and went to eat dinner? Maybe that was why the ancients had so many murders."

He noticed that the robot was getting an answer from Henry's station, and was pleased. He could talk as long as he liked, knowing Henry would not resent his cutting off any time he became bored with the conversation.

he robot focused the image smoothly. Henry gave the impression of being a small man. He was gray and wrinkled compared with Robert, but his black eyes were alertly sharp. He smiled his greeting and immediately launched into a story of one of his youthful trips through the mountains, from the point at which it had been interrupted the last time they had talked.

Robert listened impatiently.

"Maybe I have some interesting news," he remarked as the other finished. "I picked up a new station the other night."

"That reminds me of a time when I was a boy and—"

Robert fidgeted while Henry described watching his father build a spare television set as a hobby, with only a minimum of robot help. He pounced upon the first pause.

"A new station!" he repeated. "Came in very well, too. I can't imagine why I never picked it up before."

"Distant, perhaps?" asked Henry resignedly.

"No, not very far from me, as a matter of fact."

"You can't always tell, especially with the ocean so close. Now that there are so few people, you'd think there'd be land enough for all of them; but a good many spend all their lives aboard ship-robots."

"Not this one," said Robert. "She even showed me an outside view of her home."

Henry's eyebrows rose. "She? A woman?"

"Her name is Marcia-Joan."

"Well, well," said Henry. "Imagine that. Women, as I recall, usually do have funny names."

He gazed thoughtfully at his well-kept hands.

"Did I ever tell you about the last woman I knew?" he asked. "About twenty years ago. We had a son, you know, but he grew up and wanted his own home and robots."

"Natural enough," Robert commented, somewhat briefly since Henry had told him the story before.

"I often wonder what became of him," mused the older man. "That's the trouble with what's left of Earth culture—no families any more."

Now he'll tell about the time he lived in a crowd of five, thought Robert. He, his wife, their boy and the visiting couple with the fleet of robot helicopters.

Deciding that Henry could reminisce just as well without a listener, Robert quietly ordered the robot to turn itself off.

Maybe I will make the trip, he pondered, on the way downstairs, if only to see what it's like with another person about.

At about noon of the second day after that, he remembered that thought with regret.

The ancient roads, seldom used and never repaired, were rough and bumpy. Having no flying robots, Robert was compelled to transport himself and a few mechanical servants in ground vehicles. He had—idiotically, he now realized—started with the dawn, and was already tired.

Consequently, he was perhaps unduly annoyed when two tiny spy-eyes flew down from the hills to hover above his caravan on whirring little propellers. He tried to glance up pleasantly while their lenses televised pictures to their base, but he feared that his smile was strained.

The spy-eyes retired after a few minutes. Robert's vehicle, at his voiced order, turned onto a road leading between two forested hills.

Right there, he thought four hours later, was where I made my mistake. I should have turned back and gone home!

He stood in the doorway of a small cottage of pale blue trimmed with yellow, watching his robots unload baggage. They were supervised by Blue Two, the spare for Blue One.

lso watching, as silently as Robert, was a pink-and-blue striped robot which had guided the caravan from the entrance gate to the cottage. After one confused protest in a curiously high voice, it had not spoken.

Maybe we shouldn't have driven through that flower bed, thought Robert. Still, the thing ought to be versatile enough to say so. I wouldn't have such a gimcrack contraption!

He looked up as another humanoid robot in similar colors approached along the line of shrubs separating the main lawns from that surrounding the cottage.

"Marcia-Joan has finished her nap. You may come to the house now."

Robert's jaw hung slack as he sought for a reply. His face flushed at the idea of a robot's offering him permission to enter the house.

Nevertheless, he followed it across the wide lawn and between banks of gaily blossoming flowers to the main house. Robert was not sure which color scheme he disliked more, that of the robot or the unemphatic pastel tints of the house.

The robot led the way inside and along a hall. It pulled back a curtain near the other end, revealing a room with furniture for human use. Robert stared at the girl who sat in an armchair, clad in a long robe of soft, pink material.

She looked a few years younger than he. Her hair and eyes were also brown, though darker. In contrast to Robert's, her smooth skin was only lightly tanned, and she wore her hair much longer. He thought her oval face might have been pleasant if not for the analytical expression she wore.

"I am quite human," he said in annoyance. "Do you have a voice?"

She rose and walked over to him curiously. Robert saw that she was several inches shorter than he, about the height of one of his robots. He condescended to bear her scrutiny.

"You look just as you do on the telescreen," she marveled.

Robert began to wonder if the girl were feeble-minded. How else should he look?

"I usually swim at this hour," he said to change the subject. "Where is the pool?"

Marcia-Joan stared at him.

"Pool of what?" she asked.

Sensing sarcasm, he scowled. "Pool of water, of course! To swim in. What did you think I meant—a pool of oil?"

"I am not acquainted with your habits," retorted the girl.

"None of that stupid wit!" he snapped. "Where is the pool?"

"Don't shout!" shouted the girl. Her voice was high and unpleasantly shrill compared with his. "I don't have a pool. Who wants a swimming pool, anyway?"

Robert felt his face flushing with rage.

So she won't tell me! he thought. All right, I'll find it myself. Everybody has a pool. And if she comes in, I'll hold her head under for a while!

Sneering, he turned toward the nearest exit from the house. The gaily striped robot hastened after him.

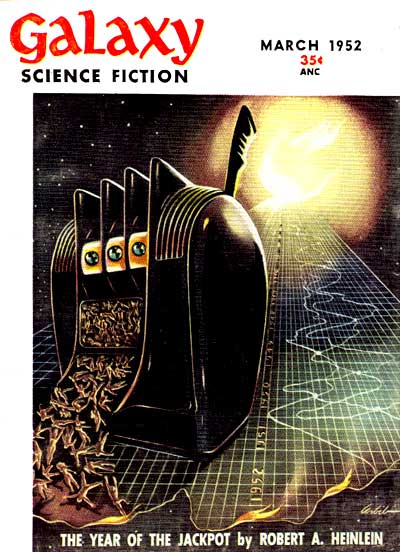

he door failed to swing back as it should have at Robert's approach. Impatiently, he seized the ornamental handle. He felt his shoulder grasped by a metal hand.

"Do not use the front door!" said the robot.

"Let go!" ordered Robert, incensed that any robot should presume to hinder him.

"Only Marcia-Joan uses this door," said the robot, ignoring Robert's displeasure.

"I'll use it if I like!" declared Robert, jerking the handle.

The next moment, he was lifted bodily into the air. By the time he realized what was happening, he was carried, face down, along the hall. Too astonished even to yell, he caught a glimpse of Marcia-Joan's tiny feet beneath the hem of her pink robe as his head passed the curtained doorway.

The robot clumped on to the door at the rear of the house and out into the sunshine. There, it released its grip.

When Robert regained the breath knocked out of him by the drop, and assured himself that no bones were broken, his anger returned.

"I'll find it, wherever it is!" he growled, and set out to search the grounds.

About twenty minutes later, he was forced to admit that there really was no swimming pool. Except for a brook fifty yards away, there was only the tiled bathroom of the cottage to bathe in.

"Primitive!" exclaimed Robert, eying this. "Manually operated water supply, too! I must have the robots fix something better for tomorrow."

Since none of his robots was equipped with a thermometer, he had to draw the bath himself. Meanwhile, he gave orders to Blue Two regarding the brook and a place to swim. He managed to fill the tub without scalding himself mainly because there was no hot water. His irritation, by the time he had dressed in fresh clothes and prepared for another talk with his hostess, was still lively.

"Ah, you return?" Marcia-Joan commented from a window above the back door.

"It is time to eat," said Robert frankly.

"You are mistaken."

He glanced at the sunset, which was already fading.

"It is time," he insisted. "I always eat at this hour."

"Well, I don't."

Robert leaned back to examine her expression more carefully. He felt very much the way he had the day the water-supply robot for his pool had broken down and, despite Robert's bellowed orders, had flooded a good part of the lawn before Blue One had disconnected it. Some instinct warned him, moreover, that bellowing now would be as useless as it had been then.

"What do you do now?" he asked.

"I dress for the evening."

"And when do you eat?"

"After I finish dressing."

"I'll wait for you," said Robert, feeling that that much tolerance could do no particular harm.

He encountered the pink-and-blue robot in the hall, superintending several plain yellow ones bearing dishes and covered platters. Robert followed them to a dining room.

"Marcia-Joan sits there," the major-domo informed him as he moved toward the only chair at the table.

obert warily retreated to the opposite side of the table and looked for another chair. None was visible.

Of course, he thought, trying to be fair. Why should anybody in this day have more than one chair? Robots don't sit.

He waited for the major-domo to leave, but it did not. The serving robots finished laying out the dishes and retired to posts along the wall. Finally, Robert decided that he would have to make his status clear or risk going hungry.

If I sit down somewhere, he decided, it may recognize me as human. What a stupid machine to have!

He started around the end of the table again, but the striped robot moved to intercept him. Robert stopped.

"Oh, well," he sighed, sitting sidewise on a corner of the table.

The robot hesitated, made one or two false starts in different directions, then halted. The situation had apparently not been included among its memory tapes. Robert grinned and lifted the cover of the nearest platter.

He managed to eat, despite his ungraceful position and what he considered the scarcity of the food. Just as he finished the last dish, he heard footsteps in the hall.

Marcia-Joan had dressed in a fresh robe, of crimson. Its thinner material was gathered at the waist by clasps of gleaming gold. The arrangement emphasized bodily contours Robert had previously seen only in historical films.

He became aware that she was regarding him with much the same suggestion of helpless dismay as the major-domo.

"Why, you've eaten it all!" she exclaimed.

"All?" snorted Robert. "There was hardly any food!"

Marcia-Joan walked slowly around the table, staring at the empty dishes.

"A few bits of raw vegetables and the tiniest portion of protein-concentrate I ever saw!" Robert continued. "Do you call that a dinner to serve a guest?"

"And I especially ordered two portions—"

"Two?" Robert repeated in astonishment. "You must visit me sometime. I'll show you—"

"What's the matter with my food?" interrupted the girl. "I follow the best diet advice my robots could find in the city library."

"They should have looked for human diets, not song-birds'."

He lifted a cover in hopes of finding some overlooked morsel, but the platter was bare.

"No wonder you act so strangely," he said. "You must be suffering from malnutrition. I don't wonder with a skimpy diet like this."

"It's very healthful," insisted Marcia-Joan. "The old film said it was good for the figure, too."

"Not interested," grunted Robert. "I'm satisfied as I am."

"Oh, yes? You look gawky to me."

"You don't," retorted Robert, examining her disdainfully. "You are short and stubby and too plump."

"Plump?"

"Worse, you're actually fat in lots of places I'm not."

"At least not between the ears!"

Robert blinked.

"Wh-wh-WHAT?"

"And besides," she stormed on, "those robots you brought are painted the most repulsive colors!"

obert closed his mouth and silently sought the connection.

Robots? he thought. Not fat, but repulsive colors, she said. What has that to do with food? The woman seems incapable of logic.

"And furthermore," Marcia-Joan was saying, "I'm not sure I care for the looks of you! Lulu, put him out!"

"Who's Lulu?" demanded Robert.

Then, as the major-domo moved forward, he understood.

"What a silly name for a robot!" he exclaimed.

"I suppose you'd call it Robert. Will you go now, or shall I call more robots?"

"I am not a fool," said Robert haughtily. "I shall go. Thank you for the disgusting dinner."

"Do not use the front door," said the robot. "Only Marcia-Joan uses that. All robots use other doors."

Robert growled, but walked down the hall to the back door. As this swung open to permit his passage, he halted.

"It's dark out there now," he complained over his shoulder. "Don't you have any lights on your grounds? Do you want me to trip over something?"

"Of course I have ground lights!" shrilled Marcia-Joan. "I'll show you—not that I care if you trip or not."

A moment later, lights concealed among the trees glowed into life. Robert walked outside and turned toward the cottage.

I should have asked her what the colors of my robots had to do with it, he thought, and turned back to re-enter.

He walked right into the closed door, which failed to open before him, though it had operated smoothly a moment ago.

"Robots not admitted after dark," a mechanical voice informed him. "Return to your stall in the shed."

"Whom do you think you're talking to?" demanded Robert. "I'm not one of your robots!"

There was a pause.

"Is it Marcia-Joan?" asked the voice-box, after considerable buzzing and whirring.

"No, I'm Robert."

There was another pause while the mechanism laboriously shifted back to its other speech tape. Then: "Robots not admitted after dark. Return to your stall in the shed."

Robert slowly raised both hands to his temples. Lingeringly, he dragged them down over his cheeks and under his chin until at last the fingers interlaced over his tight lips. After a moment, he let out his breath between his fingers and dropped his hands to his sides.

He raised one foot to kick, but decided that the door looked too hard.

He walked away between the beds of flowers, grumbling.

eaching the vicinity of the cottage, he parted the tall shrubs bordering its grounds and looked through carefully before proceeding. Pleased at the gleam of water, he called Blue Two.

"Good enough! Put the other robots away for the night. They can trim the edges tomorrow."

He started into the cottage, but his major-domo warned, "Someone comes."

Robert looked around. Through thin portions of the shrubbery, he caught a glimpse of Marcia-Joan's crimson robe, nearly black in the diffused glow of the lights illuminating the grounds.

"Robert!" called the girl angrily. "What are your robots doing? I saw them from my upstairs window—"

"Wait there!" exclaimed Robert as she reached the shrubs.

"What? Are you trying to tell me where I can go or not go? I—YI!"

The shriek was followed by a tremendous splash. Robert stepped forward in time to be spattered by part of the flying spray. It was cold.

Naturally, being drawn from the brook, he reflected. Oh, well, the sun will warm it tomorrow.

There was a frenzy of thrashing and splashing in the dimly lighted water at his feet, accompanied by coughs and spluttering demands that he "do something!"

Robert reached down with one hand, caught his hostess by the wrist, and heaved her up to solid ground.

"My robots are digging you a little swimming hole," he told her. "They brought the water from the brook by a trench. You can finish it with concrete or plastics later; it's only fifteen by thirty feet."

He expected some sort of acknowledgment of his efforts, and peered at her through the gloom when none was forthcoming. He thus caught a glimpse of the full-swinging slap aimed at his face. He tried to duck.

There was another splash, followed by more floundering about.

"Reach up," said Robert patiently, "and I'll pull you out again. I didn't expect you to like it this much."

Marcia-Joan scrambled up the bank, tugged viciously at her sodden robe, and headed for the nearest pathway without replying. Robert followed along.

As they passed under one of the lights, he noticed that the red reflections of the wet material, where it clung snugly to the girl's body, were almost the color of some of his robots.

The tennis robot, he thought, and the moving targets for archery—in fact, all the sporting equipment.

"You talk about food for the figure," he remarked lightly. "You should see yourself now! It's really funny, the way—"

He stopped. Some strange emotion stifled his impulse to laugh at the way the robe clung.

Instead, he lengthened his stride, but he was still a few feet behind when she charged through the front entrance of the house. The door, having opened automatically for her, started to swing closed. Robert sprang forward to catch it.

"Wait a minute!" he cried.

Marcia-Joan snapped something that sounded like "Get out!" over her shoulder, and squished off toward the stairs. As Robert started through the door to follow, the striped robot hastened toward him from its post in the hall.

"Do not use the front door!" it warned him.

"Out of my way!" growled Robert.

The robot reached out to enforce the command. Robert seized it by the forearm and put all his weight into a sudden tug. The machine tottered off balance. Releasing his grip, he sent it staggering out the door with a quick shove.

hasty glance showed Marcia-Joan flapping wetly up the last steps. Robert turned to face the robot.

"Do not use that door!" he quoted vindictively, and the robot halted its rush indecisively. "Only Marcia-Joan uses it."

The major-domo hesitated. After a moment, it strode off around the corner of the house. First darting one more look at the stairs, Robert thrust his head outside and shouted: "Blue Two!"

He held the door open while he waited. There was an answer from the shrubbery. Presently, his own supervisor hurried up.

"Fetch the emergency toolbox!" Robert ordered. "And bring a couple of others with you."

"Naturally, Robert. I would not carry it myself."

A moment after the robot had departed on the errand, heavy steps sounded at the rear of the hall. Marcia-Joan's robot had dealt with the mechanism of the back door.

Robert eyed the metal mask as the robot walked up to him. He found the color contrast less pleasant than ever.

"I am not using the door," he said hastily. "I am merely holding it open."

"Do you intend to use it?"

"I haven't decided."

"I shall carry you out back," the robot decided for him.

"No, you don't!" exclaimed Robert, leaping backward.

The door immediately began to swing shut as he passed through.

Cursing, he lunged forward. The robot reached for him.

This time, Robert missed his grip. Before he could duck away, his wrist was trapped in a metal grasp.

The door will close, he despaired. They'll be too late.

Then, suddenly, he felt the portal drawn back and heard Blue Two speak.

"What does Robert wish?"

"Throw this heap out the door!" gasped Robert.

Amid a trampling of many feet, the major-domo was raised bodily by Blue Two and another pair of Robert's machines and hustled outside. Since the grip on Robert's wrist was not relaxed, he involuntarily accompanied the rush of metal bodies.

"Catch the door!" he called to Blue Two.

When the latter sprang to obey, the other two took the action as a signal to drop their burden. The pink-and-blue robot landed full length with a jingling crash. Robert was free.

With the robots, he made for the entrance. Hearing footsteps behind him as the major-domo regained its feet, he slipped hastily inside.

"Pick up that toolbox!" he snapped. "When that robot stops in the doorway, knock its head off!"

Turning, he held up a finger.

"Do not use the front door!"

The major-domo hesitated.

The heavy toolbox in the grip of Blue Two descended with a thud. The pink-and-blue robot landed on the ground a yard or two outside the door as if dropped from the second floor. It bounced once, emitted a few sparks and pungent wisps of smoke, lay still.

"Never mind, that's good enough," said Robert as Blue Two stepped forward. "One of the others can drag it off to the repair shop. Have the toolbox brought with us."

"What does Robert wish now?" inquired Blue Two, trailing the man toward the stairway.

"I'm going upstairs," said Robert. "And I intend to be prepared if any more doors are closed against me!"

He started up, the measured treads of his own robots sounding reassuringly behind him....

t was about a week later that Robert sat relaxed in the armchair before his own telescreen, facing Henry's wizened visage.

The elder man clucked sympathetically as he re-examined the scratches on Robert's face and the bruise under his right eye.

"And so you left there in the morning?"

"I certainly did!" declared Robert. "We registered a marriage record at the city library by television, of course, but I don't care if I never see her again. She needn't even tell me about the child, if any. I simply can't stand that girl!"

"Now, now," Henry said.

"I mean it! Absolutely no consideration for my wishes. Everything in the house was run to suit her convenience."

"After all," Henry pointed out, "it is her house."

Robert glared. "What has that to do with it? I don't think I was as unreasonable as she said in smashing that robot. The thing just wouldn't let me alone!"

"I guess," Henry suggested, "it was conditioned to obey Marcia-Joan, not you."

"Well, that shows you! Whose orders are to count, anyway? When I tell a robot to do something, I expect it done. How would you like to find robots trying to boss you around?"

"Are you talking about robots," asked Henry, "or the girl?"

"Same thing, isn't it? Or it would be if I'd decided to bring her home with me."

"Conflict of desires," murmured Henry.

"Exactly! It's maddening to have a perfectly logical action interfered with because there's another person present to insist—insist, mind you—on having her way."

"And for twenty-odd years, you've had your own way in every tiny thing."

Somewhere in the back of Robert's lurked a feeling that Henry sounded slightly sarcastic.

"Well, why shouldn't I?" he demanded. "I noticed that in every disagreement, my view was the right one."

"It was?"

"Of course it was! What did you mean by that tone?"

"Nothing...." Henry seemed lost in thought. "I was just wondering how many 'right' views are left on this planet. There must be quite a few, all different, even if we have picked up only a few by television. An interesting facet of our peculiar culture—every individual omnipotent and omniscient, within his own sphere."

Robert regarded him with indignant incredulity.

"You don't seem to understand my point," he began again. "I told her we ought to come to my house, where things are better arranged, and she simply refused. Contradicted me! It was most—"

He broke off.

"The impudence of him!" he exclaimed. "Signing off when I wanted to talk!"

—H. B. FYFE

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Manners of the Age, by Horace Brown Fyfe

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MANNERS OF THE AGE ***

***** This file should be named 32764-h.htm or 32764-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/2/7/6/32764/

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.