[Contents]

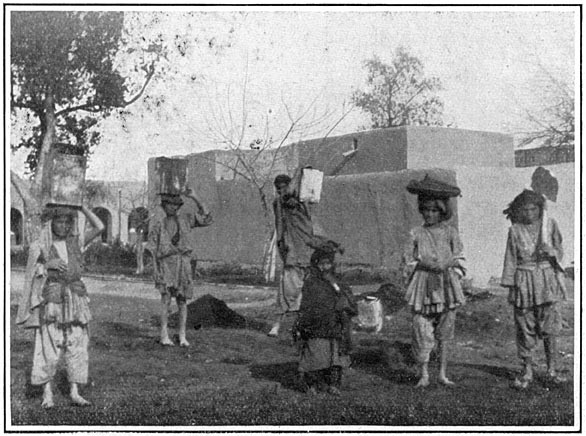

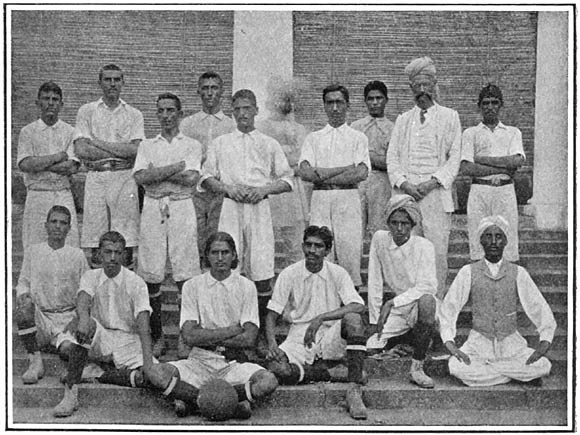

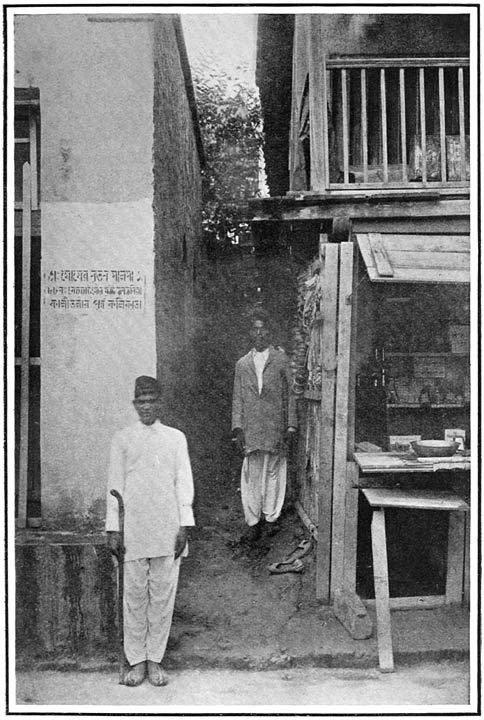

Among the Wild Tribes of the Afghan Frontier

Chapter I

The Afghan Character

Paradoxical—Ideas of

honour—Blood-feuds—A sister’s revenge—The story

of an outlaw—Taken by assault—A jirgah and its

unexpected termination—Bluff—An attempt at

kidnapping—Hospitality—A midnight meal—An ungrateful

patient—A robber’s death—An Afghan dance—A

village warfare—An officer’s escape—Cousins.

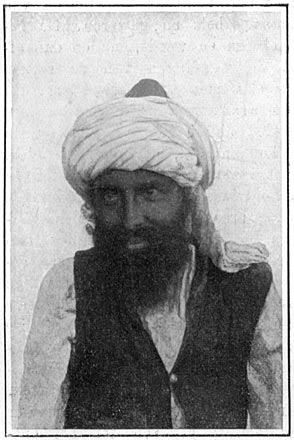

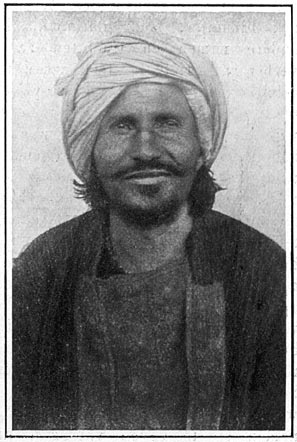

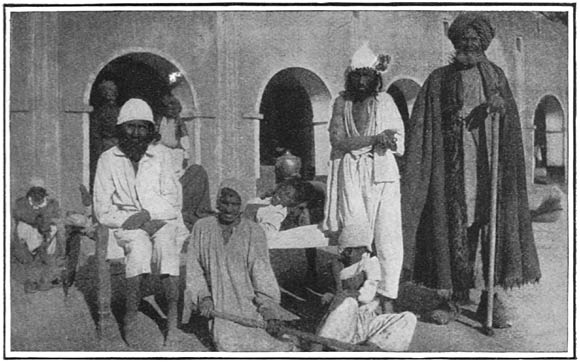

The East is the country of contradictions, and the

Afghan character is a strange medley of contradictory qualities, in

which courage blends with stealth, the basest treachery with the most

touching fidelity, intense religious fanaticism with an avarice which

will even induce him to play false to his faith, and a lavish

hospitality with an irresistible propensity for thieving.

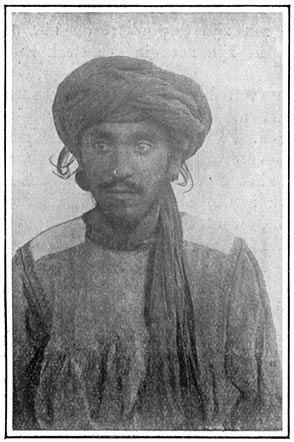

There are two words which are always on an Afghan’s

tongue—izzat and sharm. They denote the idea of

honour viewed in its positive and negative aspects, but what that

honour consists in even an Afghan would be puzzled to tell you.

Sometimes he will consider that he has vindicated his honour by a

murder perpetrated with the foulest treachery; at other times it

receives an indelible stain if at some public function he is given a

seat below some rival chief.

The vendetta, or blood-feud, has eaten into the very core of Afghan

life, and the nation can never become healthily progressive

[18]till public opinion on the question of revenge

alters. At present some of the best and noblest families in Afghanistan

are on the verge of extermination through this wretched system. Even

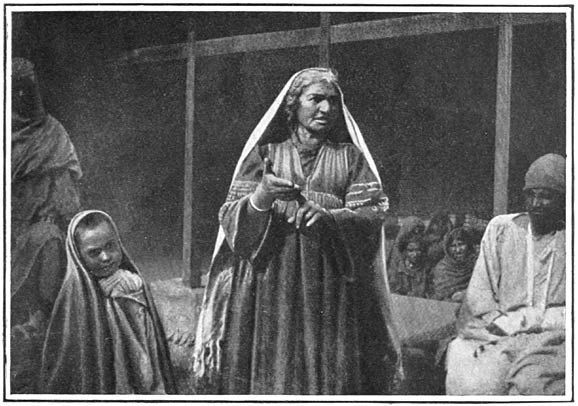

the women are not exempt. In 1905, at Bannu, there was a case where a

man had been foully murdered over some disputed land. It was generally

known who the murderer was, but as he and his relations were powerful

and likely to stick at nothing, and the murdered man had no near

relation except one sister, no one was willing to risk his own skin in

giving evidence, so when the case came up in court the Judge was

powerless to convict.

“Am I to have no justice at the hands of the

Sarkar?” passionately cried the sister in her despair.

“Bring me witnesses, and I will convict,” was all the Judge

could reply. “Very well; I must find my own way;” and the

girl left the court to take no rest till her brother’s blood,

which was crying to her from the ground, should be avenged.

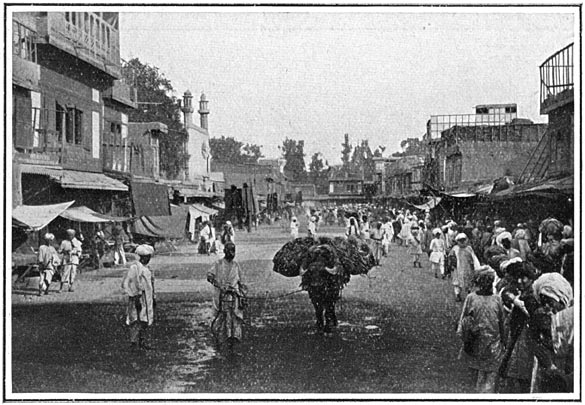

Shortly after this I was sitting in a classroom of the mission

school teaching the boys. It was a Friday morning, when thousands of

the hillmen come in to the weekly fair, and the bazaars are full of a

shouting, jostling throng, the murmur of which reaches even the

schoolroom. Suddenly a shot was heard, and then a confused shouting.

Running out on to the street hard by, I found a Wazir, quite dead, shot

through the heart. It was the murderer who had escaped the justice of

the law, but not the hand of the avenger, for the sister had concealed

a revolver on her person, and coming up to her enemy in the crowded

bazaar, had shot him point-blank. She was arrested there and then, and

the court condemned her to penal servitude for life. I met her some

weeks later as she was on the march with some other prisoners to their

destination in the Andaman Islands. Resignation and satisfaction were

her dominant feelings. “I have avenged my brother; for the rest,

it is God’s will: I am content.” Those were the words in

which she answered my inquiries. [19]

The officer who has most power with the Pathans is the one who,

while transparently just, yet deals with them with a strong hand, whose

courage is beyond question, and who, when once his mind is made up,

does not hesitate in the performance of his plans. To such a one they

are loyal to the backbone, and will go through fire and water in his

train.

“Tender-handed grasp a nettle,

It will sting you for your pains;

Grasp it like a man of mettle,

Soft as silk it then remains.”

This has its counterpart in a Pashtu proverb, and

is no doubt a true delineation of the Afghan character.

Some years ago some outlaws had fortified a village a few miles

across the border, and had there bidden defiance to the authorities

while carrying on their depredations among the frontier villages, where

they raided many a wealthy Hindu, and even carried off the rifles from

the police posts. The leader of the gang was Sailgai. His father was

Mian Khan, a Wazir of the Sparkai clan. When still a boy Sailgai showed

great aptitude and skill in archery, and when about fifteen he

commenced rifle-shooting, and soon became a noted marksman. This,

however, led him to associate with the desperadoes of the clan, and

before long he became the leader of a gang which used to go out at

night-time to break into shops and into the houses of rich Hindus. When

this occupation began to pall on him he became a highway robber, and

lay in wait with his confederates in various parts of the Kohat-Bannu

road to waylay and rob travellers both by day and night. The next step

onward—or downwards, we should say—was to become the leader

of a gang of dacoits. These men would enter a village, usually in the

late evening, and hold up the inhabitants while they looted the houses

of the rich Hindus at leisure. On these occasions they often cut off

the ears of the women as the simplest way of getting their earrings;

and fingers, too, suffered in the same way if the [20]owner

did not remove his rings quickly enough. At the same time Sailgai

became a professional murderer, and used to take two hundred to four

hundred rupees for disposing of anyone obnoxious to the payer.

Still, up to this time he had contrived to keep clear of the police,

and had never been caught. If anyone informed against him he soon

discovered who the informant was, and paid him a night visit, only

leaving after he had either killed him or taken a rich ransom. Some

eight years ago he took two hundred rupees for killing a Bizun Khel

Wazir, and went to his house one evening with fifteen of his followers.

The Wazir, however, got a warning, and made a bold stand, and Sailgai

had to fire seven times before he despatched him, and by that time the

brother of the deceased had fetched some police and followed up in

chase of Sailgai. When, however, the police saw that they had a

well-armed band to contend with, although about equal in number to the

Wazirs, they beat a hasty retreat, with the exception of one man, who

opened fire on the murderers at two hundred paces, but was hit and

disabled, so that Sailgai and his party got away in safety. Government

gave a reward to this, the one brave man, and put a price on

Sailgai’s head, so that he could no longer enter British

territory except by stealth, and he retired to his fort at Gumatti,

which he strengthened and made the base for marauding expeditions on

Government territory.

These subsequently became so frequent and so successful that the

Indian Government was finally constrained to send up a column under

Colonel Tonnochy, who was in command of the 53rd Sikhs at Bannu, to

destroy his fort once for all. Before the guns opened fire the

Political Officer, Mr. Donald, walked up alone to the loopholes of his

fort to offer Sailgai and his fellow-defenders terms. Knowing well the

long list of crimes that would be proved against him, he replied that

he had determined to sell his life as dearly as possible in the fort

where he had been born and bred; and we must say, to [21]his

credit, that they restrained their fire till Mr. Donald got back to his

own lines. Colonel Tonnochy brought the guns up to within sixty yards

of the fort, and while directing their operations he was mortally

wounded. When the tower was finally taken by storm, all Sailgai’s

companions were dead, and he himself wounded in four places. He,

however, with a last effort took aim at the British officer, Captain

White, who was bravely leading the assault, and shot him dead, and was

almost at the same moment despatched by that officer’s orderly.

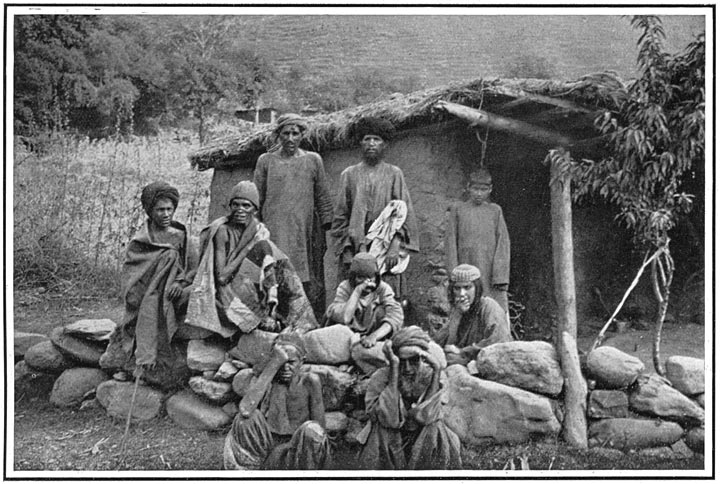

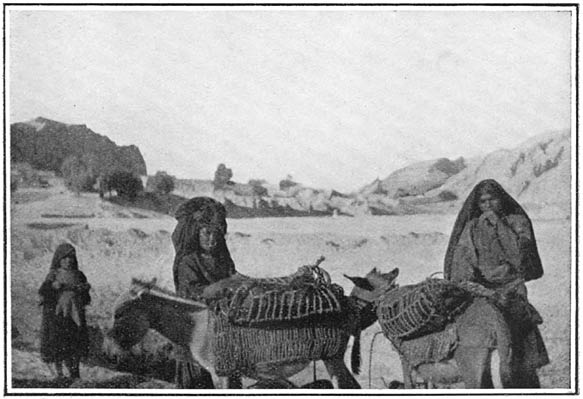

Wazirs from Gumatti, as well as from all the rest of the neighbourhood,

are constantly coming to the mission dispensary, and some of them have

been in-patients. The police munshi who made the bold stand

above mentioned was himself treated for his wound in our hospital.

The Afghan has in some respects such inordinate vanity in connection

with his peculiar ideas of sharm, and is so hot-headed in

resenting some fancied insult, that he sometimes places himself in a

ridiculous position, from which he finds it difficult to extricate

himself without still further sacrificing his honour.

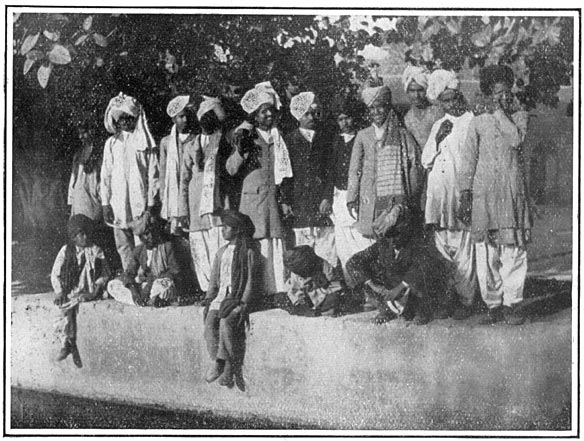

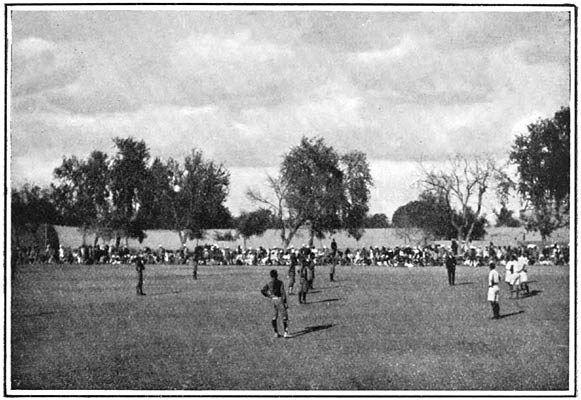

An instance of this occurred in December, 1898. The mission school

athletic sports were in progress in the mission compound, and the

political officers of the Tochi and Wano were engaged not far off in a

jirgah of the representatives of the Mahsud and Darwesh Khel

sections of the Wazirs. Suddenly the cry was raised, “The Wazirs

have attacked us!” and for a short time all was confusion. Wazirs

were seen rushing pell-mell into school, bungalow, and other buildings,

and a great part of the spectators who had gathered to see the sports

fled in confusion. It transpired, however, that, so far from the Wazirs

desiring to do us any injury, they were the Mahsuds in flight from the

Darwesh Khels, who were hot in pursuit, chasing them even into the

mission buildings where they had sought refuge. The council had been

proceeding satisfactorily, and with apparently amicable relations on

both [22]sides, when a Darwesh Khel malik, in the

excitement of debate, gesticulated too close to the seat of the

Political Officer. A Mahsud orderly, thinking he was disrespectful to

the officer, pushed him back with needless force, so that the

malik slipped and fell. The Darwesh Khels round him at once set

on the orderly, saying he had done it of malice prepense, and began to

beat him. In another moment the whole assembly were frantically

attacking each other; but the Mahsuds, being very decidedly in the

minority, found safety in flight, and, our mission compound being the

nearest rallying-place, had come down upon us in this unceremonious

manner, with the Darwesh Khels in hot pursuit. Fortunately, no serious

injury resulted, and both parties were soon laughing at their own

foolish hot-headedness.

Bluff is a very prominent characteristic of the Afghan, and this

makes him appear more formidable than he really is to those who are not

acquainted with his character. He is also a great bully and exults in

cruelty, so that he becomes a veritable tyrant to those who have fallen

into his power or are overawed by his bluff. At the same time, he has a

profound reverence for the personification of power or brute force, and

becomes a loyal and devoted follower of those whom he believes to be

his superiors. It is often asked of me whether I carry a revolver or

other arms when travelling about among these wild tribes. For a

missionary to do so would not only be fatal to his chance of success,

but would be a serious and constant danger. It would be impossible for

him to be always on his guard; there must be times when, through

fatigue or other reasons, he is at the mercy of those among whom he is

dwelling. Besides this, there is nothing which an Afghan covets more,

or to steal which he is more ready to risk his life, than firearms; and

though he might not otherwise wish harm to the missionary, the

possibility of securing a good revolver or gun would be too great a

temptation, even though he had to shed blood to secure it. [23]My plan

was, therefore, to put myself entirely in their hands, and let them see

that I was trusting to their sense of honour and to their traditional

treatment of a guest for my safety.

At the same time, I was rather at pains than otherwise to let them

see that the bluff to which they sometimes resorted had no effect upon

me, and that I was indifferent to their threats and warnings, which, as

often as not, were just a ruse on their part to see how far they could

impose on me. Once, when I was in a trans-border village, resting a few

hours in the heat of the day, some young bloods arrived who had just

come in from a raid, and were still in the excitement of bloodshed.

Some of them thought it would be a good opportunity to bait the

Daktar Sahib, and one of them, holding his loaded revolver to my

chest, said: “Now we are going to shoot you.” I replied:

“You will be very great fools if you do, because I am of more use

to you than to myself, and you would as likely as not poison yourselves

with my drugs if I were not there to tell you how to use them.”

At this the senior man of the party rebuked them, and offered me a kind

of apology for their rudeness, saying: “They are only young

fellows, and they are excited. Do not mind what they say. We will see

that no harm comes to you.” On another occasion I came to a

village across the border rather late at night. There were numerous

outlaws in the village, but the chief under whose protection I placed

myself took the precaution of putting my bed in the centre of six of

his retainers, fully armed, in a circle round me, one or two of whom

were to keep watch in turns. I had had a hard day’s work, and was

soon sound asleep, and this was my safety, because I was told in the

morning that some of the more fanatical spirits had wanted to kill me

in the night, but the others said: “See, he has trusted himself

entirely to our protection, and because he trusts us he is sleeping so

soundly; therefore, no harm must be done to him in our

village.”

Not long ago there was a notorious outlaw on the frontier

[24]called Rangin, who had been making a practice of

kidnapping rich Hindus, and then holding them to ransom. I was in the

habit of visiting our out-station at Kharrak about once a month, and

usually went alone and by night. Information was brought that Rangin,

knowing of this, intended one day to kidnap me, and hold me to a high

ransom. The next time I visited Kharrak, I purposely slept by the

roadside all night in a lonely part, that the people might see that I

was not afraid of Rangin’s threats. Needless to say, no harm came

of it; but the people there in the countryside spread the idea that, as

there was an angel protecting the Daktar Sahib, it would be a

useless act of folly to try to do him an injury.

Although the honour which an Afghan thinks is due to his guest has

often stood me in good stead, yet sometimes the observance of the

correct etiquette has become irksome. A rich chief will be satisfied

with nothing less than the slaying of a sheep when he receives a guest

of distinction; a poorer man will be satisfied with the slaying of a

fowl, and the preparation therefrom of the native dish called

pulao. On one occasion I came to a village with my companions

rather late in the evening. The chief himself was away, but his son

received me with every mark of respect, and killed a fowl and cooked us

a savoury pulao, after which, wearied with the labours of the

day, we were soon fast asleep. Later on, it appeared, the chief himself

arrived, and learnt from his son of our arrival. “Have you killed

for him the dumba?” he at once asked; and, on learning

from his son that he had only prepared a fowl, he professed great

annoyance, saying: “This will be a lasting shame (sharm)

for me, if it is known that, when the Bannu Daktar Sahib came to

my village, I cooked for him nothing more than a fowl. Go at once to

the flock, and take a dumba, and slay and dress it, and, when

all is ready, call me.” Thus it came about that about 1 a.m. we

were waked up to be told that the chief had come to salaam us, and that

[25]dinner was ready. It would not only have been

useless to protest that we were more in a mood for sleep than for

dinner, but it would also have been an insult to his hospitality; so we

got up with alacrity and the best grace possible, and after a

performance of the usual salutations on both sides, we buckled to that

we might show our appreciation of the luscious feast of roast mutton

and pulao that had been prepared for us.

On one occasion, in turning back to Bannu from a journey across the

frontier, I had an escort of two villainous-looking Afghans, who

appeared as though they would not hesitate at any crime, however

atrocious. They, however, looked after us with the greatest attention,

and brought us safely into Bannu. On arrival there, I offered them some

money as a reward for their good conduct; they, however, refused it

with some show of indignation, saying that to take money from one who

had been their guest would be contrary to their best traditions.

Consequently, I sent them over to rest for the night at the house of

one of my native assistants, with a note to give them a good dinner,

and send them away early in the morning. He gave them the dinner, but

when he got up in the morning to see them off, he found that they had

already decamped with all his best clothes.

Among the Afghans theft is more or less praiseworthy, according to

the skill and daring shown in its perpetration, and to the success in

the subsequent evasion of pursuit. Two years ago an Afghan brought his

little daughter for an operation on her eye. The operation was

successfully performed, and the day of discharge came. Meanwhile the

eyes of the Afghan had lighted on my mare, and he thought how useful it

would be to him on his travels, and the night following his discharge

we found that he had come with a friend and taken the horse away.

Unfortunately for the success of the undertaking, he had an enemy, who,

when a reward was offered for the discovery of the thief, thought he

might enrich himself [26]and pay off an old grudge at the same time.

The culprit had, however, by this time arrived with his capture safely

across the Afghan frontier into Khost, and no laws of extradition apply

there. Other members of the tribe, however, reside in British India,

and would be going up with their families into the hills as the heat of

summer increased. The Deputy Commissioner called for the chiefs of the

tribe, and informed them that until they arranged for the return of the

mare, he would be reluctantly compelled to issue orders that they were

not to go up to the hills with their families. At first they protested

that they had no control over the thief, whom they had themselves

turned out of their tribe because he was a rascal; but when they found

that the officer knew them too well to be hoodwinked by their bluff,

they found it convenient to send up into Khost and bring back the mare.

The man through whose instrumentality it was brought back has posed to

me ever since as my benefactor, and expected a variety of favours in

return. The theft was universally reprobated by the tribe, but chiefly

because circumstances had doomed it to failure.

Notorious thieves and outlaws have frequently availed themselves of

the wards of the mission hospital when suffering from some fever or

other disease which has temporarily incapacitated them; but, of course,

they come under assumed names, and otherwise conceal their identity. It

is to be hoped, however, that they benefit all the same from the

addresses and good counsel which they daily hear while under treatment.

Sometimes, as in the case I am about to relate, their identity becomes

known. A few years ago, in Bed 26—the “Southsea”

bed—there was Zaman, a noted thief, who came in suffering from

chronic dysentery, and continued under treatment for over two months.

He lingered on, with many ups and downs, but was evidently past

recovery when he came in. He paid much attention to the Gospel that was

read to him, and sometimes professed belief in it, but showed no

[27]signs of repenting of his past career. But when

told eventually that there was no hope of his recovery, he at once had

a police officer summoned, so as to give him the names of some of his

former “pals,” hoping thereby not only to get them caught

and punished in revenge for their having thrown him off when too weak

and ill to join in their nefarious practices, but also to gain a reward

for the information given. He gradually sank and died, professing a

belief in Christ; but He alone, who readeth the heart, knoweth. I do

not think he would have turned informer had not his confederates

apparently deserted him in his distress.

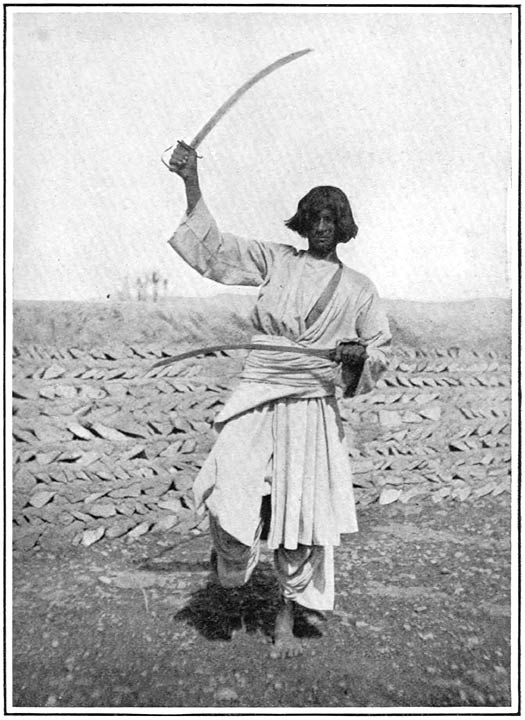

No description of Afghan life would be complete which did not give

an account of their public dances. These take place on the

’Id days, or to celebrate some tribal compact, or the

cessation of hostilities between two tribes or sections. It can only be

seen in its perfection across the border, for in British India the more

peaceful habits of the people and the want of the requisite firearms

have caused it to fall into desuetude. Across the frontier some level

piece of ground is chosen, and a post is fixed in the centre. The men

arrange themselves in ever-widening circles round this centre and

gyrate round it, ever keeping the centre on the left, so as to give

greater play to their sword-arms. The older and less nimble of the

warriors form the inner circles; outside them come the young men, who

dance round with surprising agility, often with a gun in one hand and a

sword in the other, or, it may be, with a sword in each hand, which

they wave alternately in circles round their heads. Outside them,

again, circle the horsemen, showing their agility in the saddle and

their skill with the sword or gun at the same time. On one side are the

village minstrels, who give the tune on drums and pipes. They begin

with a slow beat, and one sees all the circles going round with a

measured tread; then the music becomes more and more rapid, and the

dancers become more and more carried away with excitement, and to the

onlooker [28]it appears a surging mass of waving swords and

rifles. The rifles are as often as not loaded and discharged from time

to time, at which the gyrations of the horsemen on the outside become

more and more excited, and one wonders that heads and arms are not

gashed by the swords which are seen waving everywhere. Suddenly the

music ceases, and all stop to regain their breath, to start again after

a few minutes, until they are tired out. The excitement and the

intricate revolutions often bring the scene to the brink of a real

warfare, and not infrequently it ends in bloodshed. In one instance,

where a man fell, and in falling discharged his rifle with fatal effect

into another dancer, the unintentional murderer would have had his

throat cut there and then had not his friends hurriedly dragged him out

and carried him off to his home, fighting as they went. In this way

blood-feuds are sometimes started, which will divide a village into two

factions, and not end till some of the bravest have fallen victims to

it.

On one occasion I was seated with some Afghans in a house in the

village of Peiwar in the Kurram Valley. Most of the houses were on

either side of one long street running the length of the village, and I

noticed that some little doors had been made from house to house all

down the street, and on inquiring the object of this, I was told that

some time before a great faction fight had been carried on in the

village. One side of the street was in one faction and the other side

in the other faction, and they were always in ambush to fire at each

other across the street. The only way to get to the village supply of

water was to go from house to house down to the bottom of the street,

and in order to do this without exposure, doors had been made, while by

common consent they had agreed not to shoot while getting their

supplies from the stream at the bottom. My host went on to show me

sundry holes in his door and in the wooden panels of the windows, which

the bullets of his neighbours across the [29]street had penetrated,

and said: “It was behind that hole in the door there that my

uncle was shot; that hole in the window was made by the bullet which

killed my brother.” Pointing to another Afghan who had come into

the room and seated himself on the bed, he said: “That is the man

who shot my brother.” On my remarking upon the peace and goodwill

in which they appeared to be living at the present time, he said:

“Yes, we are good friends now, because the debt is even on both

sides. I have killed the same number in his family.” After a

faction fight of this kind, the fatalities on both sides are added up,

and if they can be found to be equal, both sides feel that they can

make peace without sacrificing their izzat (honour), and

amicable relations are resumed, it being thought unnecessary to

investigate who were the real instigators or murderers. If, however,

one side or the other believes itself to be still aggrieved, or not to

have exacted the full tale of lives required by the law of revenge,

then the feud may go on indefinitely, until whole families may become

nearly exterminated. The avenger will go on waiting his opportunity for

months or years, but he will never forget; and one will always remember

the hunted look and the furtive expression and nervous handling of the

revolver and cartridges which mark the man who knows that one or more

such avenger is on his track.

A Political Officer in the Kurram Valley was once visiting a chief

of the village of Shlozan, who, like all chiefs, had a high tower, in

which he would seek security from his enemies at night. His host took

him up into the tower, after carefully seeing that a window in the

upper story was shut. The officer, thinking he would like a view of the

country round, went to open it, but was hurriedly and unceremoniously

pulled back by the chief, who told him that his cousin had been

watching that window for months in the hope of having an opportunity of

shooting him there. The officer made no further attempt to look out of

the window, but some months [30]later he heard that his friend the

chief, having inadvertently gone to the open window, had been shot

there by his cousin. So universal is the enmity existing between

cousins in Afghanistan that it has become a proverb that a man is

“as great an enemy as a cousin,” the causes of such feuds

being such as are more likely to arise between those who have some

relationship. The causes of 90 per cent. of such feuds are described by

the Afghans as belonging to one of three heads—zan,

zar, and zamin, these being the three Persian words

meaning women, money, and land; and disputes are more likely to arise

between cousins than between strangers on such matters as these.

[31]

[Contents]

Chapter II

Afghan Traditions

Israelitish origin of the Afghans—Jewish

practices—Shepherd tradition of the Wazirs—Afridis and

their saint—The zyarat or

shrine—Graveyards—Custom of burial—Graves of holy

men—Charms and amulets—The medical practice of a

faqir—Native remedies—First aid to the wounded—Purges

and blood-letting—Tooth extraction—Smallpox.

A controversy as to the origin of the Afghans

centres round the question as to whether they are the children of

Israel or not; and there are two opposing camps, one regarding it as an

accepted historical fact that they are descended from the lost ten

tribes of Israel, and the other repudiating all Israelitish affinities

except such as may have come to them through the Muhammadan religion.

The Afghans themselves—at least, the more intelligent part of the

community—will tell you that they are descended from the tribe of

Benjamin, and will give you their genealogy through King Saul up to

Abraham, and they almost universally apply the term

“Bani-Israil,” or children of Israel, to themselves. Wolff,

the traveller, relates that an Afghan, Mulla Khodadad, gave him the

following history: Saul had a grandson called Afghána, the

nephew of Asaph, the son of Berachiah, who built the Temple of Solomon.

One year and a half after Solomon’s death he was banished from

Jerusalem to Damascus on account of misconduct. In the time of

Nebuchadnezzar the Jews were driven out of Palestine and taken to

Babylon. The descendants of Afghána residing at Damascus, being

Jews, were also carried to Babylon, from whence they [32]removed,

or were removed, to the mountain of Ghor, in Afghanistan, their present

place of residence, and in the time of Muhammad they accepted his

religion.

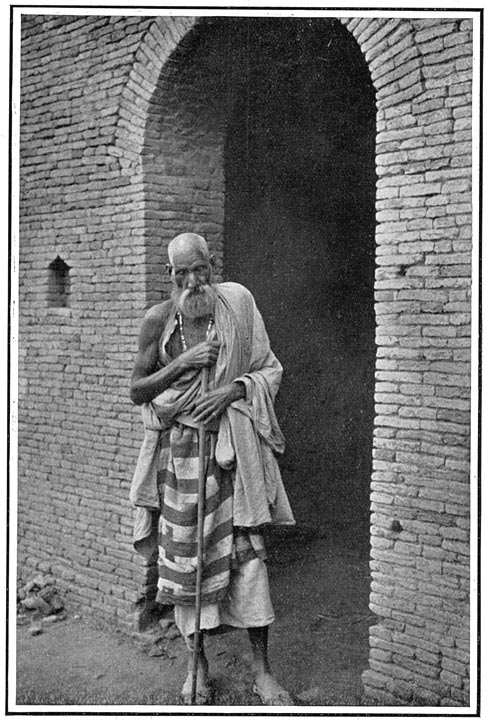

To most observers the Afghan has a most remarkably Jewish cast of

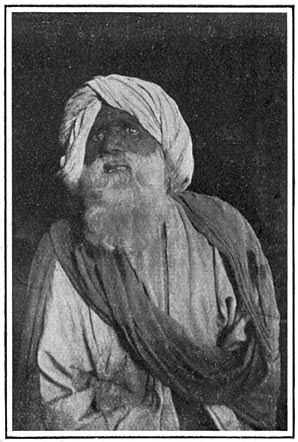

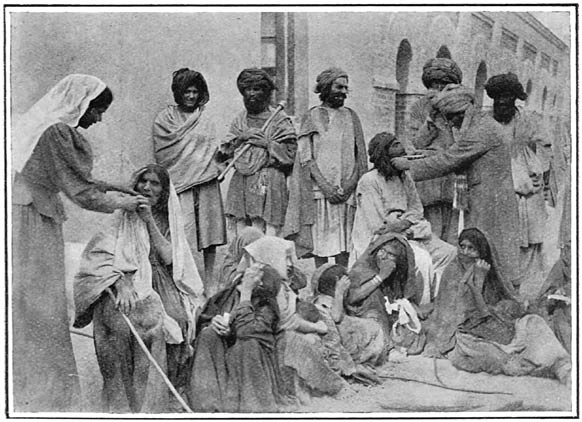

features, and often in looking round the visitors of our out-patient

department one sees some old greybeard of pure Afghan descent, and

involuntarily exclaims: “That man might for all the world be one

of the old Jewish patriarchs returned to us from Bible history!”

All Muhammadan nations must, from the origin of their religion, have

many customs and observances which appear Jewish because they were

adopted by Muhammad himself from the Jews around him; but there are

two, at least, met with among Afghans which are not found among

neighbouring Muhammadan peoples, and which strongly suggest a Jewish

origin. The first, which is very common, is that of sacrificing an

animal, usually a sheep or a goat, in case of illness, after which the

blood of the animal is sprinkled over the doorposts of the house of the

sick person, by means of which the angel of death is warded off. The

other, which is much less common, and appears to be dying out, is that

of taking a heifer and placing upon it the sins of the people, whereby

it becomes qurban, or sacrifice, and then it is driven out into

the wilderness. The Afghan, more than most Muhammadans, delights in

Biblical names, and David, Solomon, Abraham, Job, Jacob, and many other

patriarchs, are constant inmates of our hospital wards. New Testament

names, such as King Jesus (Mihtar Esa) and Simon are occasionally met

with. The ceremonies enacted at the Muhammadan

“’Id-i-bakr,” or Feast of Sacrifice, have a most

extraordinary similarity to the Jewish Passover; but as these have a

religious, and not a racial, origin and signification, and can be read

in any book on Muhammadanism, it is unnecessary to describe them here.

The strongest argument against their Jewish origin is the almost entire

disappearance [33]of any Hebrew words from their vocabulary; but

this may be partly, at least, explained by their admixture at first

with Chaldaic, and subsequently with Arab, races. The Wazirs have a

tradition as to their origin, which, although its Biblical resemblance

may be accidental, is yet certainly remarkable when found among so wild

and barbarous a race. The tradition is that a certain ancestor had two

sons, Issa and Missa (probably Jesus and Moses). The latter was a

shepherd, and one day while tending his flocks on the hills a lamb

strayed away and could not be found. Missa, leaving his other sheep,

went in search of the lost one. For three days and nights he wandered

about the jungle without being able to find it. On the morning of the

fourth day he found it in some distant valley, and, instead of being

wroth with it, he took it up in his arms, kissed it, and brought it

safely back to the flock. For this humane act God greatly blessed him,

and made him the progenitor of the Wazir tribe. Though it would seem to

us more appropriate had this action been attributed to Issa instead of

to Missa, yet this tradition has often given me a text for explaining

the Gospel story to a crowd of these wild tribesmen.

Though all Afghans are fanatically zealous in the pursuit of their

religion, yet some are so ignorant of its teachings that more civilized

Muhammadans are hardly willing to admit their right to a place in the

congregation of the faithful. The Wazirs, for instance, who would

always be ready to take their share in a religious war, are not only

ignorant of all but the elementary truths of Muhammadanism, but the

worship of saints and graves is the chief form that their religion

takes. The Afridis are not far removed from them in this respect, and

it is related of a certain section of the Afridis that, having been

taunted by another tribe for not possessing a shrine of any holy man,

they enticed a certain renowned Seyyed to visit their country, and at

once [34]despatched and buried him, and boast to this day

of their assiduity in worshipping at his sepulchre.

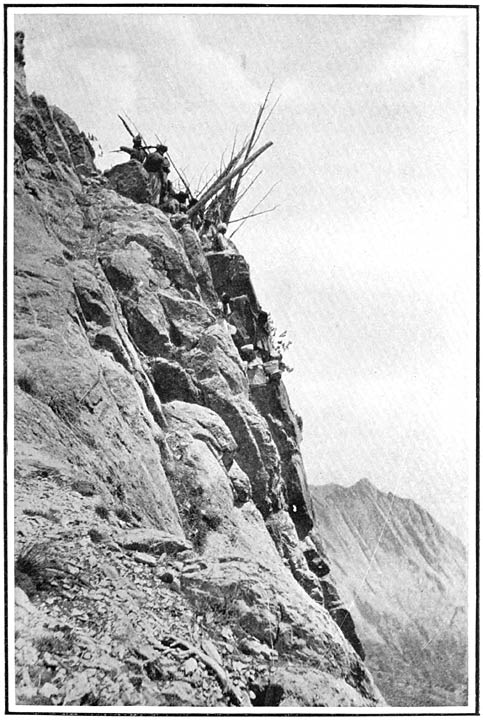

The frontier hills are often bare enough of fields or habitations,

but one cannot go far without coming across some zyarat, or holy

shrine, where the faithful worship and make their vows. It is very

frequently situated on some mountain-top or inaccessible cliff,

reminding one of the “high places” of the Israelites. Round

the grave are some stunted trees of tamarisk or ber (Zisyphus

jujuba). On the branches of these are hung innumerable bits of rag

and pieces of coloured cloth, because every votary who makes a petition

at the shrine is bound to tie a piece of cloth on as the outward symbol

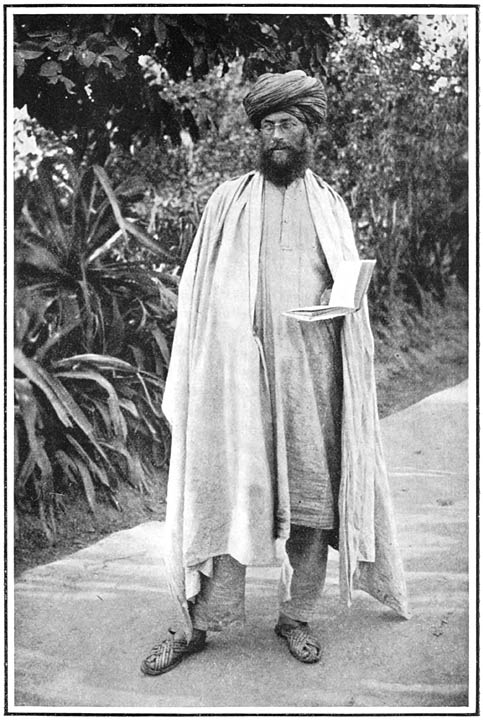

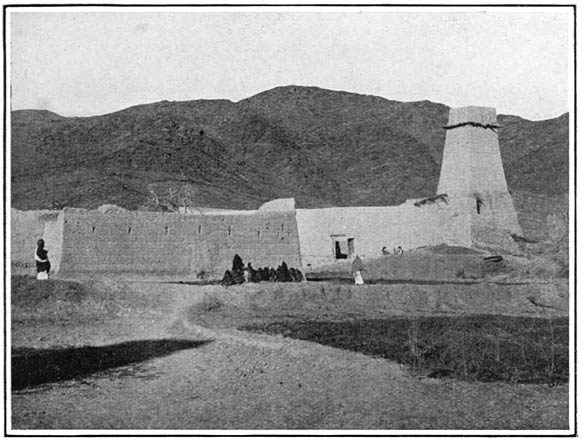

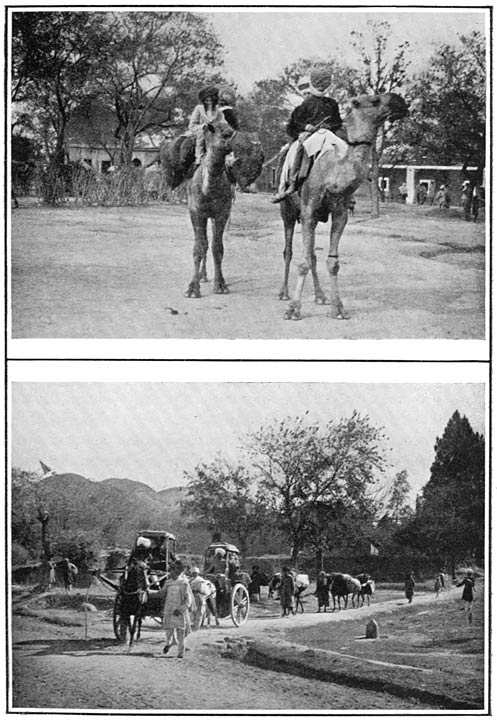

of his vow. In the accompanying photograph is seen a famous shrine on

the Suliman Range. Despite its inaccessibility, hundreds of pilgrims

visit this yearly, and sick people are carried up in their beds, with

the hope that the blessing of the saint may cure them. Sick people are

often carried on beds, either strapped on camels or on the shoulders of

their friends, for considerably more than a hundred miles to one or

other of these zyarats. In some cases it may reasonably be

supposed that the change from a stuffy, unventilated dark room to the

open air, and the stimulus of change of climate and scenery, has its

share in the cure which often undoubtedly results.

Another feature of these shrines is that their sanctity is so

universally acknowledged that articles of personal property may be

safely left by the owners for long periods of time in perfect

confidence of finding them untouched on their return. This is the more

remarkable, remembering that these tribes are thieves by profession,

and scarcely look upon brigandage as a reprehensible act. The

inhabitants of a mountain village may be migrating to the plains for

the winter months, and they will leave their beds, pots and pans, and

other household furniture, under the trees of some neighbouring shrine,

and they will almost invariably find them on their return, some

[35]months later, exactly as they left them. One

distinct advantage of these shrines is that it is a sin to cut wood

from any of the trees surrounding them. Thus it comes about that the

shrines are the only green spots among the hills which the improvident

vandalism of the tribes has denuded of all their trees and shrubs.

Graves have a special sanctity in the eyes of the Afghans, more even

than in the case of other Muhammadans, and you will generally see an

Afghan, when passing by a graveyard, dismount from his horse and,

turning towards some more prominent tomb, which denotes the

burial-place of some holy man, hold up his hands in the attitude of

Muhammadan prayer, and invoke the blessing of the holy man on his

journey, and then stroke his beard, as is usually done by the

Muhammadans at the conclusion of their prayers. There are few

graveyards which do not boast some such holy man or faqir in their

midst; in fact, as often as not, the chance burial of some such holy

man in an out-of-the-way part determines the site of a cemetery,

because all those in the country round desire to have their graves near

his, in the belief that at the Resurrection Day his sanctity will atone

for any of their shortcomings, and insure for them an unquestionable

entry into bliss. The graves always lie north and south, and after

digging down to a depth determined by the character of the soil, a

niche is hollowed out at one side, usually the western, and the corpse

is laid in the niche, with its face turned towards Mecca. Some bricks

or stones are then laid along the edge of the niche, so that when the

earth is thrown in none of it may fall on the corpse, which is

enveloped in a winding-sheet only, coffins being never used. The origin

of the word “coffin” is possibly from the Arabic word

kafn, which denotes the winding-sheet usually used by

Muhammadans.1

Great marvels are related about the graves of these holy

[36]men, among the commonest being the belief that

they go on increasing in length of their own accord, the increase of

length being a sign of the acceptance of the prayers of the deceased by

the Almighty. Near the mission house in Peshawur was one such grave,

which went on lengthening at the rate of one foot a year. When it had

reached the length of twenty-seven feet it was seriously encroaching on

the public highway, and it was only after the promulgation of an

official order from the district authorities that the further growth of

the holy man should cease that the grave ceased to expand. This shrine

is still famous in the country round as “the Nine-Yard

Shrine,” which numbers of devotees visit every year, in the

expectation of obtaining some material benefit.

The use of charms or amulets is practically universal. The children

of the rich may be seen with strings of charms fastened up in little

ornamented silver caskets hung round their neck, while even the poorest

labourer will not be without a charm sewn up in a bit of leather, which

he fastens round his arm or his neck. These charms are most usually

verses out of the Quran, transcribed by some Mullah of repute and

blessed by him; others are cabalistic sentences or words, while some

are mere bits of paper or rag which have been blessed by a holy man. On

more than one occasion I have found my prescriptions made up into

charms, the patient believing that this would be more efficacious than

drinking the hospital medicines; in fact, one patient assured me that

he had never suffered from rheumatism, to which he had previously been

subject, after he had tied round his arm a prescription in which I had

ordered him some salicylate of soda, although he had never touched the

drug. In one instance I found that a man who had been given some grey

powders, with directions how to use them, had instead fastened them up,

paper and all, into a little packet, which he had sewn up in leather

and fastened round his neck, with, he told me, very beneficial result.

From this it can be readily understood that Mullahs [37]and

faqirs who pretend to have the power of making charms for all known

diseases, and sell them to the people at large, are often able to

enrich themselves far more rapidly than a doctor who confines himself

to the ordinary methods of treatment.

Once, when I was in camp, I came across a mountebank who was making

quite a large fortune in this way. He had travelled over a large part

of South-Western Asia, but did not stop long in any one place, as no

doubt his takings would soon begin to wear off after the first days of

novelty. One of his performances was to walk through fire, professedly

by the power of the Muhammadan Kalimah. A trench was dug in the

ground, and filled with charcoal and wood, which was set alight. After

the fire had somewhat died down, the still glowing embers were beaten

down with sticks, and then the faqir, reciting the Kalimah with

great zest, proceeded to deliberately walk across, after which he

invited the more daring among the faithful to follow his example,

assuring them that if they recited the creed in the same way and with

sincerity, they would suffer no harm. Some went through the ordeal and

showed no signs of having suffered from it; others came out with

blistered and sore feet. These unfortunates were jeered at by the

others as being no true Muhammadans, owing to which they had forfeited

the immunity conferred upon them by the recitation of the creed. One

young Sikh student, calling out the Sikh battle-cry, ventured on the

ordeal, and came out apparently none the worse. The Muhammadans looked

upon this as an insult to their religion, because Muhammadans oftener

than not heard that cry when the Sikhs had been engaged in mortal

combat with them, and this action of the young Sikh appeared to them to

be a challenge as to whether the Muhammadan or the Sikh cry had the

greater magic power. However, some of the more responsible persons

present checked the more hot-headed ones, and the affair passed off

with a little scoffing. Every morning [38]and afternoon the faqir

prepared for the reception of the patients, who were collected in great

numbers on hearing of his fame. Each applicant had to give 5 pice to

the assistant as his fee. He was then sent before the faqir, who

remained seated on a mat. The faqir asked him one or two questions as

to the nature of the illness, wrote out the necessary charm, and passed

on to the next. Three or four hundred people were often seen at one

sitting. This would give about 50 rupees (£3. 6s. 8d.) as a

day’s takings. Some days would, no doubt, be occupied in travelling, and

others less fruitful; but his equipment and his method of travelling

showed that it was a very profitable business. He was stopping in the

rest-house, and invited me to dinner, which was served in English

fashion. He entertained me with stories of his travels, and made no

secret of the fact that he took advantage of the credulity of the

people to run a good business. When dinner was nearly over an assistant

came in to say that there were many people outside clamouring for

charms. With an apology to me for the interruption, he took a piece of

paper, tore it up into squares, quickly wrote off the required number,

and gave them to the assistant to go on with. In some cases, especially

those suffering from rheumatism or old injuries or sprains, he used

rubbings and manipulations, much as a so-called bone-setter does, and

these, no doubt, helped the charm to do its work.

The medical and surgical treatment of the faqirs is extremely crude.

Sometimes Jogis and herbalists from India travel about the country and

practise a certain amount of yunani, or Hippocratic medicine;

but the native doctors of Afghanistan have extremely little knowledge

of medicine. The two stock treatments of Afghanistan are those known as

dzan and dam. Dzan is a treatment habitually used

in cases of fever, whether acute or chronic, and in a variety of

chronic complaints, which they do not attempt to diagnose. It consists

in stripping the patient to the skin and placing [39]him on a

bed. A sheep or a goat is then killed and rapidly skinned. The patient

is then wrapped up in the skin, with the raw surface next him and the

wool outside. He is then covered up with a number of quilts. When

successful, this treatment acts by producing a profuse perspiration,

and when it is removed—on the second day in the summer and the

third day in the winter—the patient is sometimes found to be free

from fever, though very worn and weak from the profuse sweating. If the

first application is not successful, it may be repeated several times.

In a case of severe injury to one of the limbs, the same treatment is

often applied locally. In the case of a fractured thigh, for instance,

the sheepskin is tied on, a rough splint applied externally, and often

left for a week or more. Where there has been an open wound, and the

patient has been brought several days’ journey through the heat

down to our hospital in Bannu, you can usually anticipate the character

of the case by seeing the men who have carried the bed in carefully

winding their pagaris round their noses and mouths before

proceeding to unbandage it for your inspection, and when it is at last

opened all except the doctor and his assistant try to get as far away

as possible. A surgeon can scarcely be confronted with a more complete

antithesis to his modern ideas of aseptic surgery than a case like

this, and many and prolonged applications of antiseptics and deodorants

are required before the wound begins to assume a healthy aspect, even

if inflammation and gangrene have not rendered amputation a necessity.

In the case of a small wound, the whole or a part of the skin of a fowl

is used in the same way, the flesh of the slaughtered animal being

always a part of the fee of the doctor.

The other remedy, or that known as the dam, is akin to what

is known in Western surgery as a “moxa.” A piece of cloth

is rolled up in a pledget of the size of a shilling, steeped in oil,

placed on the part selected by the doctor, and set alight. It burns

down into the flesh, and a hard slough is [40]formed; this gradually

separates, and leaves an ulcer, which heals by degrees. This remedy is

used for every conceivable illness, a particular part of the body being

selected according to the disease or the diagnostic ability of the

doctor who applies the remedy. Thus, in people who have suffered from

indigestion you will often see a line of scars down each side of the

abdomen. For neuralgia, it is applied to the temples; for headache, to

the scalp; for rheumatism, to the shoulders; for lumbago, to the loins;

for paralysis, to the back; for sciatica, to the thighs; and so on

indefinitely. I have counted as many as fifty scars, each the size of a

shilling, on one patient as the result of repeated applications of this

remedy. The Afghans have extraordinary faith in both these treatments,

and I have sometimes sat in a village listening to an argument in which

some young fellow, lately returned from a visit to a mission hospital,

recounted the wonderful things he had seen there, to which some old

conservative greybeard retorted: “What do we want with all these

new-fangled things? The dzan and the dam are sufficient

for us.” As formerly in the West, so still in Afghanistan, the

village barber performs the ordinary surgical operations, such as

opening an abscess or lancing a gum.

The women all claim a greater or less knowledge of such surgery and

medicine as they think necessary for them. After one of the village

frays, when the warriors come back to their homes more or less cut and

wounded, the women of the household at once set about their treatment.

If there is severe hæmorrhage some oil is quickly raised to

boiling-point in a saucepan, and either poured into the wound, or if,

for instance, a limb has been cut off, the bloody stump is plunged into

the oil. This, no doubt, acts as an effective, though somewhat

barbarous, hæmostatic. If the bleeding is only slight, a certain

plant gathered from the jungle is reduced to ashes, and these ashes

rubbed on the wound. In the case of a clean cut the women draw out

hairs from their own [41]head, and sew it up with their ordinary

sewing-needles, and I have sometimes seen flesh wounds which have been

quite skilfully sewn up in this way. They are less skilful in the

application of splints. In most neighbourhoods there is some village

carpenter who prides himself on his skill in the application of splints

to broken bones; but in most cases he bandages them too tightly, or

with too little knowledge of the circulation of the limb, so that not a

year passes in which we do not get one or more cases of limbs which

have become gangrenous after quite simple fractures through this kind

of treatment.

Almost the only drugs which are used to any extent in Afghanistan

are purgatives, and especially those of a more violent and drastic

nature. Nearly every Afghan thinks it necessary to be purged or bled,

or both, every spring, and not unfrequently at the fall of the year

too. Scarcely any illness is allowed to go to a week’s duration

without the trial of some violent purge. Sometimes the purge is given

with so little regard to its quantity and the vitality of the patient

that it results in rapid collapse and death. In other cases a latent

dysentery is excited, which may result in an illness lasting many

months, and leaving the patient permanently weakened thereby. The

seasonal blood-lettings are performed, as in the West, from the bend of

the arm, this position having, no doubt, come down to the practitioners

of both East and West from the ancient Greeks; but in the case of

illness, while the physicians of the West have had their practice

revolutionized by modern ideas of anatomy and physiology, those of the

East still follow the humoral and hypothetical pathologies of

Hippocrates and his predecessors. These practitioners know the

particular vein in the particular limb or part of the body which has to

be selected for venesection in any particular illness. I have known a

young doctor from England lose at once the confidence which the people

might up to that time have had in his medical knowledge, [42]because

in a case of illness to which he was called he recommended venesection,

and the patient’s medical attendant who was to carry out the

treatment made the, to him, very natural inquiry, “From what

vein?” The English doctor said: “It does not matter.”

Both patient and medical attendant not unnaturally assumed that he was

either a very careless doctor or an ignoramus, and, in either case,

that they had better call in a fresh opinion.

Cataract is a very common complaint in Afghanistan, and from time

immemorial there have been certain hakims, or native

practitioners, who operate on this by means of the old process of

couching. These men usually itinerate about the country from village to

village, as in most cases the old men and the old women who are

suffering from cataract are unable to undertake the journey to a town

where one of these practitioners lives; or it may be that their

relations are not willing to take the trouble for someone whose working

days are apparently over. In some cases no doubt the operation results

in good sight, but in the majority other changes which take place in

the eye as a result of the operation lead before long to total

blindness. As, however, the hakim seldom goes over the same

ground again till after the lapse of several years, his reputation does

not lose by these failures, as it would have done if he were always

resident in one place. The tooth extracting of the village is usually

entrusted to the village blacksmith, who has a ponderous pair of

forceps, a foot and a half to two feet long, hung up in his shop for

the purpose. Where the crown of the tooth is fairly strong and

prominent the operation generally results in a short struggle, and then

the removal of the aching tooth; but if the tooth is very carious, or

not prominent enough for a good grip, the results are often disastrous,

even to fracture of the jaw, and these ultimately come to the mission

hospital for repair, several often turning up in one day.

At one time smallpox was terribly rife in Afghanistan, and

[43]even now no village can be visited without seeing

many who are permanently disfigured by it. When an Afghan comes to

negotiate about the price of an eligible girl for marrying to his son,

one of the first questions asked is, “Has she had the

smallpox?” and if not, either the settlement may be postponed

until she is older, or else some deduction is made for her possible

disfigurement if attacked by the disease. Many times fathers have

brought their daughters to the hospital with the scars left by smallpox

in their eyes, begging me to remove them, not so much for the sake of

the patient as because the market value of the daughter will be so much

enhanced thereby. The custom of inoculation was at one time almost

universal in Afghanistan. A little of the crust of the sore of a

smallpox patient was taken and rubbed into an incision made in the

wrist of the person to be inoculated. The smallpox resulting, though

usually mild, was sometimes so severe as to cause the death of the

patient, and the people have not been slow to recognize the great

advantages which vaccination has over inoculation. Only two

circumstances deter the people from universally profiting by the

facilities offered by the British Government. The first reason is that

very often the vaccinators are underpaid officials, who use their

opportunities for taking bribes from the people, and make the whole

business odious to them. The other is, that they have a widespread

superstition that the Government are really seeking for a girl, who is

to be recognized by the fact that when the vaccinator scarifies her

arm, instead of blood, milk will flow from the wound; she is then to be

taken over to England for sacrifice, and the parents are afraid lest

their girl should be the unlucky one. [44]

[Contents]

Chapter III

Border Warriors

Peiwar Kotal—The Kurram Valley—The

Bannu Oasis—Independent tribes—The Durand line—The

indispensable Hindu—A lawsuit and its sequel—A Hindu

outwits a Muhammadan—The scope of the missionary.

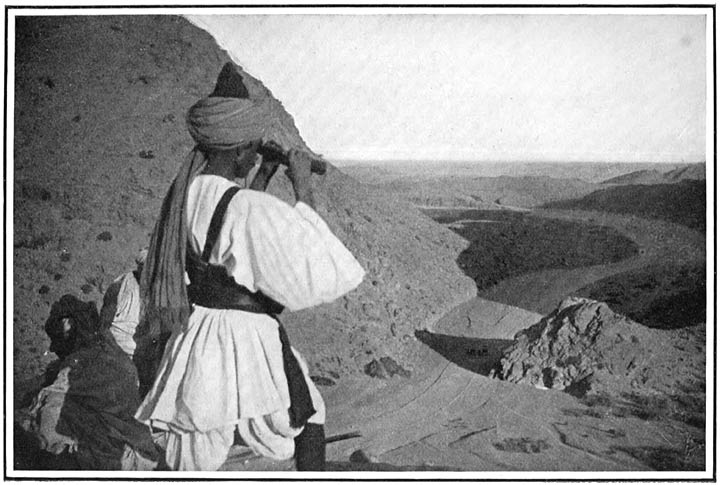

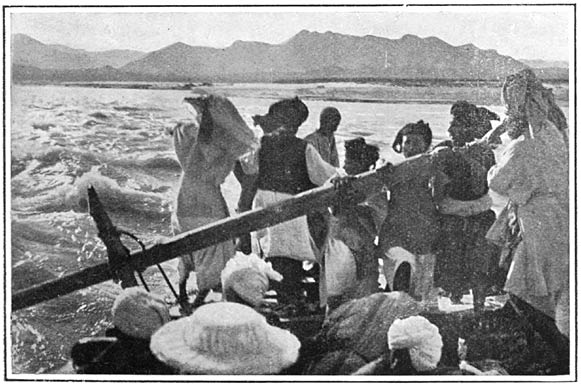

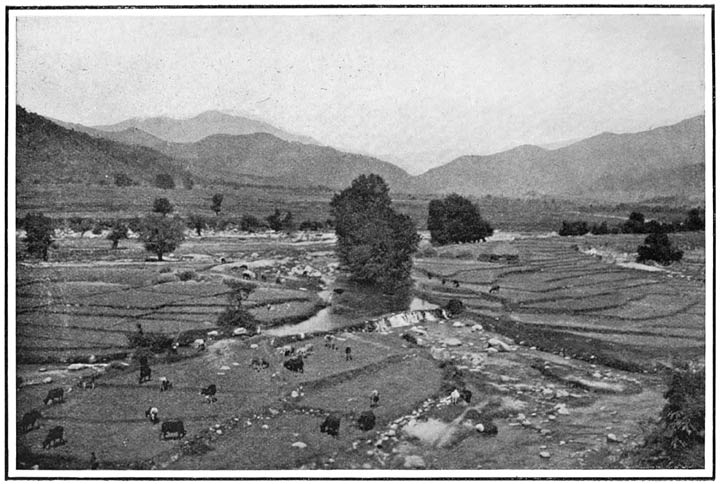

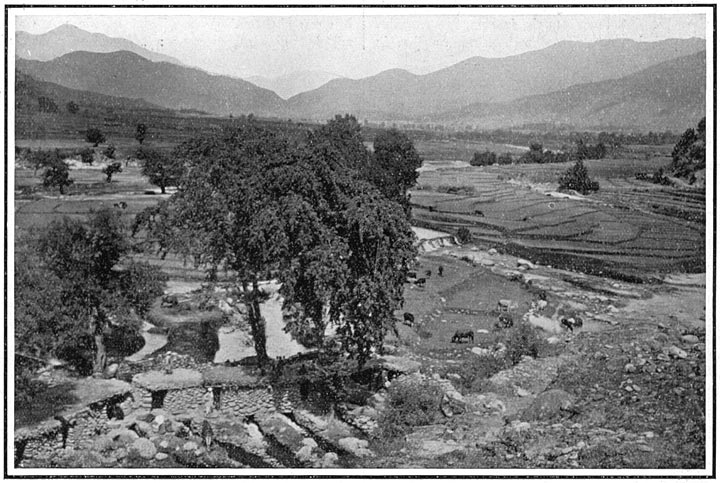

I was standing on a pine-clad spur of the Sufed Koh

Range, which runs westwards towards Kabul, between the Khaiber Pass on

the north and the Kurram Pass on the south. The snow-clad peaks of Sika

Ram, which rise to a height of fifteen thousand feet, tipped by fleecy

white clouds, were just behind me, while in front was the green valley

of the Kurram River, spread out like a panorama before me, widening out

into a large plain in its upper part, where numerous villages, partly

hidden in groves of mulberry and walnuts, nestled among the lower spurs

of the mountains, while farther down the hills on either side of it

closed in and became more rugged and bare, and the river wound its

circuitous path through defile and gorge, till it debouched on the

plains of India. Immediately before me was the pine-covered Pass of

Peiwar, which will always be memorable as the scene of the great battle

fought between the forces of the Amir, Sher Ali, and the advancing

column of Sir Frederick Roberts. There were the pines covering the

crest where the Afghan batteries were ensconced, and one could trace

without difficulty the circuitous path up the stony bed of the mountain

torrent, through a deep ravine, and then winding up among the

pine-woods, by which the gallant regiments of the advancing army

stormed and finally captured the Afghan position. [45]Westward

of the pass was a fertile valley, dotted over with villages here and

there, forming part of the territory of the Amir of Afghanistan. A few

miles below the top of the pass could be seen the fort where the

soldiers of the Amir guarded his frontier. Turning eastward, some dozen

miles off, could be seen the cantonments of Parachinar, the westernmost

cantonments of British occupation, and the seat of administration of

this trans-border valley. There was a fort garrisoned by the local

levies of the Kurram Militia—Afghans from the villages round,

who, under the training and influence of three or four British

officers, have become part of the “far-flung battle line”

of the defences of the Empire.

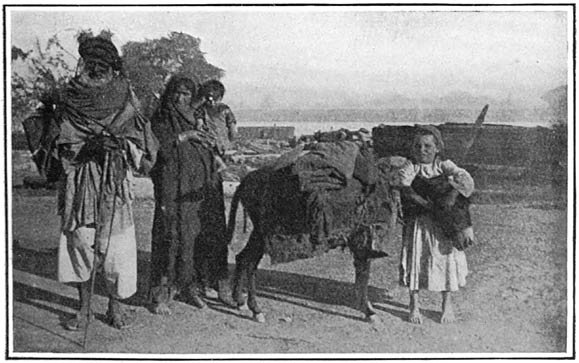

I had been spending some weeks among the people of this district,

and the time had come for reluctantly leaving the shady groves and cool

breezes of the Upper Kurram for the sweltering plains of Bannu, which

even now I could see in the eastern distance covered by heat haze,

recalling the punkahs and restless nights which were soon to be my lot

instead of the bracing air of the Sufed Koh. Our tents and baggage had

been loaded up on some mules, which we could see winding along the

white road below us, while we were lingering behind to take a last

leave of the hearty Afghans, who had been both our hosts and our

patients. Three times had we to pitch our nightly camp before we

crossed the border of British India and entered the border town of

Thal, which is the first town in British India which a traveller from

Afghanistan enters. From the time of crossing the Afghan frontier till

now, he has been going through what is known as an

“administrative area.” Here was a fort, occupied by troops

of the Indian Army, under command of a British officer.

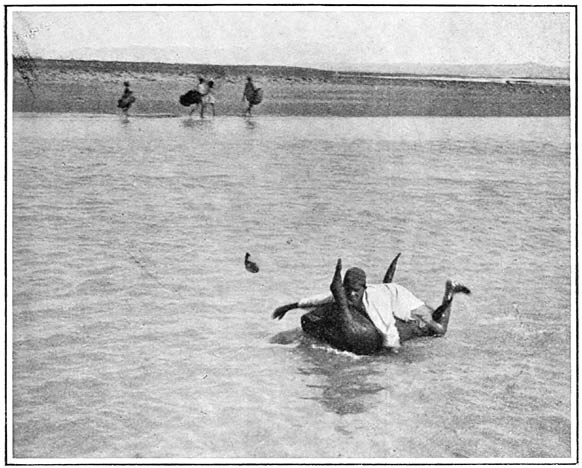

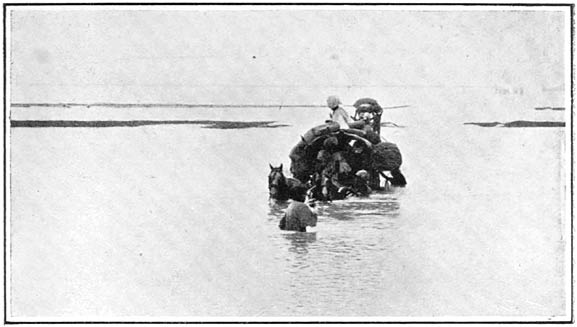

Thirty-four miles still remained in a direct line between us and our

destination in Bannu, and before accomplishing this special

arrangements had to be made with the tribes occupying [46]it for

our escort; for this tongue of country running up between Thal and

Bannu was not British India, nor even an administrative area, but

independent, and owned by the marauding Wazir tribe, who owed

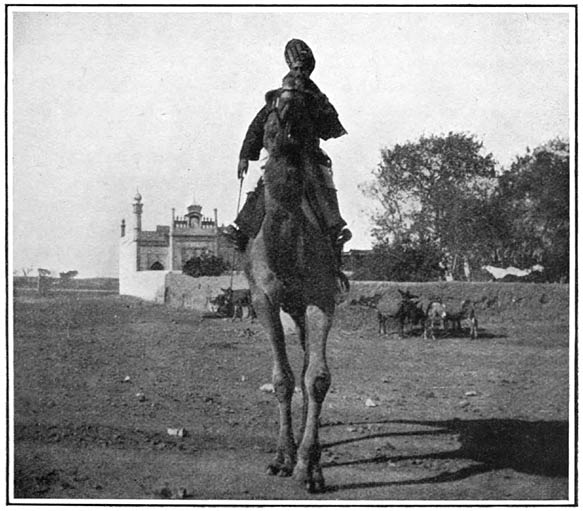

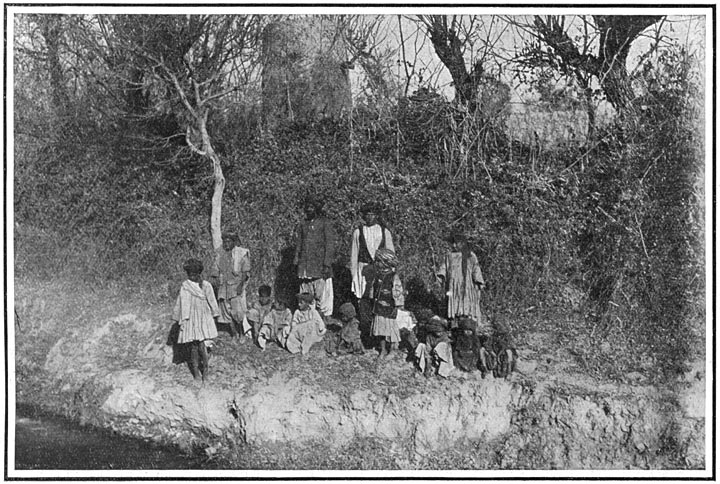

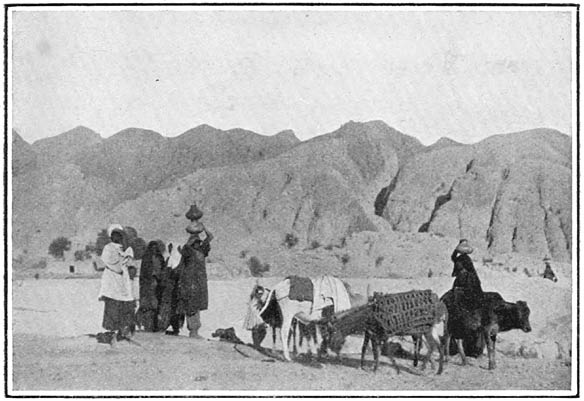

allegiance to neither Amir nor Viceroy. A couple of ruffianly-looking

Wazirs arrived to escort us down. Their rifles were slung over their

shoulders, and well-filled cartridge belts strapped round their waists;

a couple of Afghan daggers were ensconced in the folds of the dirty red

pagaris which they had bound round their bodies, and they

carried their curved Afghan swords in their hands. We had now left the

fertile valley of Upper Kurram behind us, and wandered through a

succession of rocky mountain defiles, over precipitous spurs, and along

the stony bed of the river for more than thirty miles. The lower

mountain ranges separating Afghanistan from India form by their

intricacy and precipitate nature a succession of veritable chevaux de frise, which by their natural difficulties maintain

the parda or privacy of the wild tribes inhabiting them, who

value the independence of their mountain fastnesses more than life

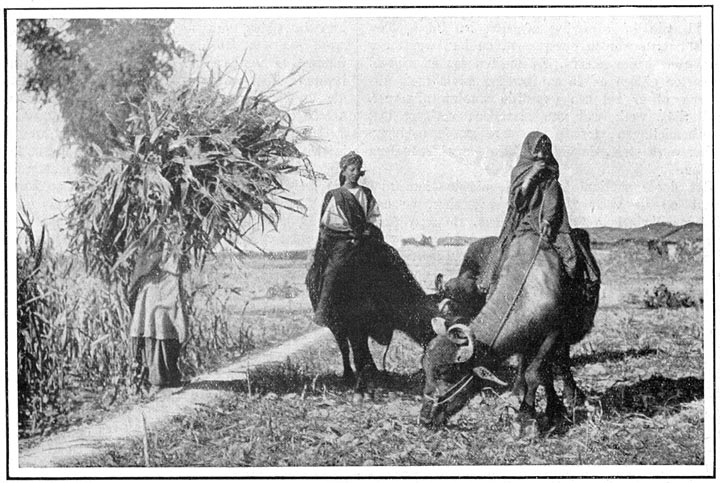

itself. Here and there is a patch of arable land in a bend of the

Kurram River, overlooked by the walled and towered village of its

possessors, who have won it by force of arms, and only keep it by their

armed vigils, even the men who are ploughing behind their oxen having

their rifles hung over their shoulders, and keeping their eyes open for

a possible enemy. In some places a channel from the river has been

carried with infinite labour on to a flat piece of ground among the

mountains, where a scanty harvest is reaped. For the rest the hill

seems to be almost devoid of animal or vegetable life. A few partridges

starting up with a shrill cry from a tuft of dry grass in front of one

are occasionally seen, and stunted trees of ber and acacia

supply a certain amount of firewood, which some of the Wazirs gather

and take down to the Friday Fair in Bannu.

[47]

The Afghans will tell you that when God created the world there were

a lot of stones and rocks and other lumber left over, which were all

dumped down on this frontier, and that this accounts for its

unattractive appearance. There is one more range of hills to surmount

before we reach the plains of India. We have toiled up a rocky path,

from the bare stones of which the rays of the summer sun are reflected

on all sides, without any relief from tree or shrub, or even a tuft of

green grass, till the ground beneath our feet seems to glow with as

fierce a heat as that of the blazing orb above us. We have reached the

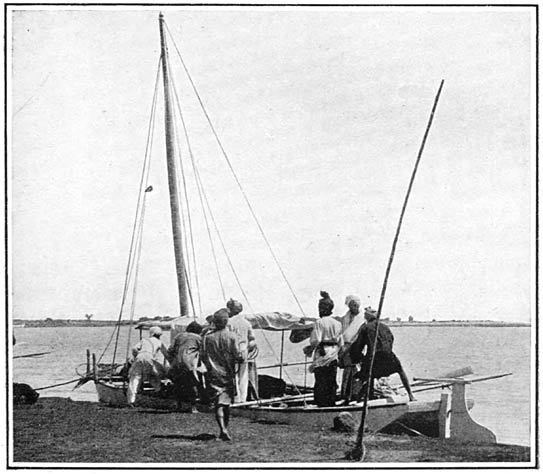

summit, and the vista before us changes as if by magic. Five hundred

feet below us is the broad plain of India, irrigated in this part by

the vivifying waters of the Kurram River, which, liberated from the

rock-bound defile through which they have wandered for the last thirty

miles, now dashing over their stony bed, anon hemmed in by dark

overhanging cliffs, are at last free to break up into numberless

channels, which, guided by the skill of the agriculturist, form a

labyrinth of silver streaks in the plain below us. As far as the

life-giving irrigation cuts of the Kurram River extend are waving

fields of corn, sugar-cane, maize, rice, turmeric, and other crops,

spread in endless succession as far as the eye can reach.

Scattered among the fields are the teeming villages of the

Bannuchies, partly hidden in their groves of mulberries and figs and

their vineyards, as though Cornucopia, wearied by the barren hills

above them in Afghanistan, had showered down all her gifts on the

favoured tribes below. Such is India as it appears to the Pathans

inhabiting the hills on our North-West Frontier, and when we see it

thus after some time spent with them in their barren and rocky hills,

we can readily understand that two thoughts are dominant in their

minds. The one is: “Those rich plains have been put there, in

contiguity to our mountains, because God intended them to be our lawful

prey, that when we have no harvest we may [48]go down and reap theirs;

and when we are hard up, and have a big fine to pay to the British

Government, we may lighten some of the wealthy Hindus of the money that

they have accumulated through usury and other ways which God

hates.” The other thought is: “What possible reason has the

British Government, the overlord of such rich lands, for coming and

interfering with us in our mountain homes, which, though nothing but

rocks and stones, are still our homes for all that, where we resent the

presence and interference of any stranger?”

The reader will have observed that in the journey above described,

from Peiwar down to Bannu, four different territories have been passed

through. The first and the last—viz., Afghanistan and British

India—are two well-defined, easily comprehensible geographical

areas; but it is seen that betwixt the two are various other tribal

areas, in varying relations with the Indian Government. A few words

must be said to familiarize the reader with the political conditions

obtaining there. The frontier of British India is well defined, but

that of Afghanistan was more or less uncertain until the year 1893,

when Sir Mortimer Durand was deputed by the British Government to meet

the officers delegated by the Amir Abdurrahman, in order that the

frontier might be delimited. This frontier is since known as the

“Durand Line.” The intervening area between the Durand Line

and the British frontier is in varying relations to the Indian

Government.

Some parts of this, such as Tirah (the country of the Afridis and

Orakzais) and Waziristan (the country of the Wazirs and Mahsuds), are

severely left alone, provided the tribes do not compel attention and

interference by the raids into British territory, which are frequently

perpetrated by their more lawless spirits.

These raids are no doubt disapproved of by the majority of the

tribesmen, who recognize the fact that they must stand [49]to lose

in any conflict with the British Government; but such is the democratic

spirit of the people that every man considers himself as good as his

neighbour, and a step better if he has a more modern rifle. As in the

interregnums of the days of the Israelitish Judges, each man does what

seems good in his own eyes, and bitterly resents any effort of his

neighbour, and even of the tribe, to control his actions or curtail his

liberty. Thus it happens that it is really very difficult for the

tribal elders to prevent their bad characters from perpetrating these

raids. The raiders are usually men with nothing to lose, owning no

landed property within the confines of British India, and guilty of

previous murders or other crimes, which make it impossible for them to

enter the country, except surreptitiously, as they would certainly be

imprisoned, and perhaps hanged, if caught.

A great number in the tribe own lands on both sides of the border,

and find it to their interest to take no overt part against the

Government; while at the same time, unless they give asylum to the

desperadoes, and conceal them on occasion, they are liable to be

themselves the victims. Thus it happens that in nearly every frontier

expedition there are some sections of the tribe which desire to be on

good terms with the British, and are known as “friendlies.”

It is difficult for a military commander who has not previously known

the people to appreciate this, and when he finds his camp being sniped

from a supposed “friendly” village, he not unnaturally

doubts the sincerity of the people. As likely as not, however, the

recalcitrant sections of the tribe have been at pains to snipe from

such points as to implicate the friendly sections and force them into

joining the standard of war. On one occasion the exasperated General

refused to believe the representations of the Political Officer that

the villages from the neighbourhood of which the sniping came were

friendly until he left the camp and went over to live in the (supposed)

enemies’ village himself! The well-disposed clans [50]would

welcome an administration of the country by which these lawless spirits

could be kept in check.

Then, there are certain semi-independent States, such as Chitral and

Dir, where there are rulers of sufficient paramount power to govern

their own country and to render it possible for the British to maintain

that amount of control of their external relations which is considered

desirable, by means of a Political Agent attached to the court of the

chief, while still leaving the latter free to manage his own internal

affairs in accordance with the customs of his tribe and the degree of

his own supremacy over the often conflicting units composing it.

Thirdly, there are what are known as “administered

areas,” such as the Upper Kurram Valley, above mentioned. These

are inhabited by tribes over whom no one chief has been able to gain

paramount authority for himself, where, as is so often the case among

Afghans, the tribe is eaten up by a number of rival factions, none of

which are willing to acknowledge the rule of a man from a faction not

their own. The Government official, therefore, is unable to treat with

one ruler, but has to hear all the members of the contending factions.

So great is the democratic spirit that any petty landowner thinks he

has as much right to push his views of public policy as the

representative of an hereditary line of chiefs. This naturally greatly

complicates official relations, and the Political Officer, however much

he would like to refrain from interference in tribal home policy, finds

that, amid a host of conflicting units, he is the only possible court

of appeal. This results in an intermediate form of government: the

Indian Penal Code does not obtain; tribal laws and customs are the

recognized judicial guides, and there is a minimum of interference with

the people; yet the Political Officer is the supreme authority, and

combines in himself the executive and judicial administration of the

area.

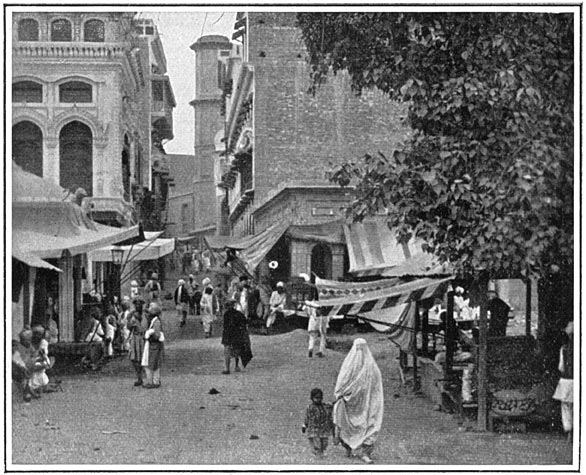

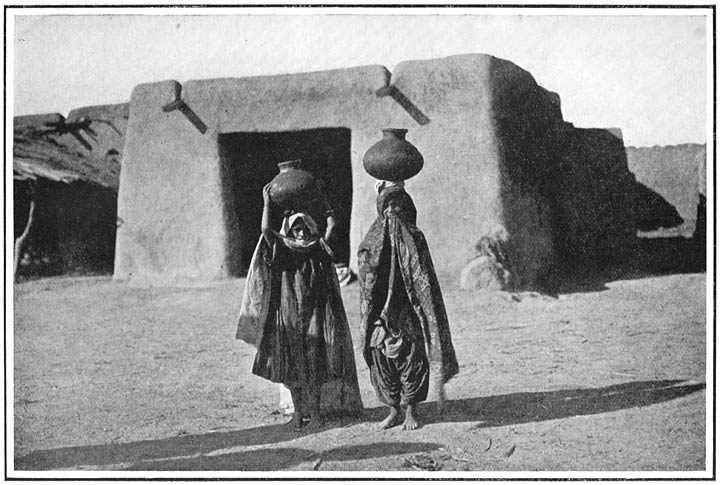

Notwithstanding the exclusiveness of the religion that [51]these

people profess, they find it impossible to do their business or live

comfortably without the help of the ubiquitous and obsequious Hindu.

Just as much as the great Mughal Emperors of old found it best to have

Hindus for the posts of treasurer, accountant, adviser, etc., so the

frontier chief of to-day has his Hindu vassal always with him, to keep

his accounts, write his petitions, and transact most of his written and

judicial business. The majority of the shopkeepers also are Hindus.

Even under the settled administration of British India the Muhammadan

has never become such an adept at bargaining, petty trade, and

shopkeeping as the more thrifty and quick-witted Hindu. Thus in every

village of any pretension there are the Hindus, with their shops, who

make their journeys to the big market-towns on the

frontier—Peshawur, Bannu, and Dera Ismail Khan—and return

with piece-goods, matches, looking-glasses, and a variety of Western

trinkets, as well as the food-stuffs which the Afghan covets, but

cannot produce himself, such as white sugar and tea. These Hindus are

regarded as vassals by the Muhammadan community they supply, and each

Hindu trader or shopkeeper has his own particular overlord or

Muhammadan malik, who in return for these services guarantees

his safety, is ready to protect him—by force of arms, if

necessary—from rival Muhammadan sections, and to revenge any

injury done to him as if it were a personal one to himself.

The Hindu supplies the brains and the Muhammadan the valour. The

Hindu is ever ready to outwit his overbearing but often obtuse masters,

and under British rule avails himself of the protection the law affords

to do things he would not venture on across the border. Once when

travelling across the border my guide was an outlaw, who had been

obliged to fly from British territory after committing a murder. He

told me that he had gone into partnership with a Hindu for an extensive

contract for road-making: the Hindu was to supply the capital and keep

accounts, and [52]he was to recruit the coolies and do the

supervision of the work. “While I,” he said, “was

broiling and sweating in the summer sun, that pig of a Hindu was

comfortably seated in his office falsifying the accounts, and I never

got an anna for all my labours. I thought I should get justice from the

Sarkar, so I brought a civil action against him; but I was a

plain man, and he learnt all about the ways of the law from some

pleader friend of his, and I lost the case. Then I paid another pleader

a big sum to take my appeal to the Sessions Judge, but he had

manipulated the accounts and paid the witnesses, so that I lost that

too. Allahu Akbar! The Judge gave his verdict before the shadow

had turned [before midday], and before the time of afternoon prayers

had arrived that son of a pig was as dead as a post. But then I had to

come over here, and I can only pay an occasional night visit to my

village now.”

A story which he told me to illustrate the mercantile genius of the

Hindu will bear repeating. A Muhammadan and a Hindu resolved to go into

partnership. The Muhammadan, being the predominant partner, stipulated

that he was to have the first half of everything, and the Hindu the

remainder. The Hindu obsequiously consented. The first day the Hindu

brought back a cow from market. He milked it, got the butter and cream,

made the dung into fuel-cakes for his fire, and then went to call the

Muhammadan because the cow was hungry and wanted grass and grain. The

Muhammadan said he was ready to do his share if the Hindu did his. The

Hindu blandly replied that he had already done his, while the

stipulated “first half” of the cow included the

animal’s mouth and stomach, and fell clearly to the lot of the

Muhammadan.

Now let us see what is the position of the missionary in each of

these areas. In British India he has a free hand so long as he keeps

within the four corners of the law. In Afghanistan there is an absolute

veto against even his entry [53]into the country, and there is no

prospect of this changing under the present régime. A convert

from Muhammadanism to Christianity is regarded within the realms of the

Amir as having committed a capital offence, and both law and popular

opinion would decree his destruction. In the intervening tribal areas

there is no reason why a cautious missionary, well acquainted with the

language and customs of the people, should not work with considerable

success. A medical missionary who did not attack their religion with a

mistaken zeal would undoubtedly be welcomed by the greater number of

the people, though the Mullahs, or priests, would be an uncertain

element, and certainly hostile at the beginning. The local political

authorities have the final say as to how far the missionaries may

extend their operations. I shall revert to this subject in the

concluding chapter (Chapter XXV.), where I shall

show that in no part of the country are medical missions more obviously

indicated, not only for Christianizing the people, but equally so for

pacifying them and familiarizing them with the more peaceful aspects of

British rule. [54]

[Contents]

Chapter IV

A Frontier Valley

Description of the Kurram Valley—Shiahs and

Sunnis—Favourable reception of Christianity—Independent

areas—A candid reply—Proverbial disunion of the

Afghans—The two policies—Sir Robert Sandeman—Lord

Curzon creates the North-West Frontier Province—Frontier

wars—The vicious circle—Two flaws the natives see in

British rule: the usurer, delayed justice—Personal influence.

Among the various tracts of border territory that

have recently been opened up and brought under the influence of

civilization by the frontier policy of the Indian Government, none is

fairer or more promising than the Upper Kurram Valley, on the lower

waters of which river Bannu, the headquarters of the Afghan Medical

Mission, is situate. The River Kurram rises on the western slopes of

Sikaram, the highest point of the Sufed Koh Range (15,600 feet), and

for twenty-five miles makes a détour to the south and east

through the Aryab Valley, which is inhabited by the tribe of Zazis, who

are still under the government of the Amir, and form his frontier in

this part. The river then suddenly emerges into a wider basin, the true

valley of Upper Kurram, stretching from the base of the Sufed Koh Range

to the base of a lower range on the right bank, a breadth of fifteen

miles, the river running close to the latter range, and the

north-western corner of this basin being separated from the head-waters

of the Kurram by the ridge of the Peiwar Kotal, where was fought the

memorable action of December 2, 1879, by which the road to Kabul was

opened. This wide valley runs down as far as Sadr, thirty miles lower

down [55]towards the south-east, being narrower, however,

below. Here the valley narrows down to from two to four miles, and runs

south-east for thirty-five miles to Thal, where it ceases to be in

British territory, but winds for thirty miles among the Waziri Hills,

until it emerges into the Bannu Plain, and flows through the Bannu and

Marwat districts into the Indus at Isa Khel. Thus, with the exception

of the head-waters and some thirty miles just above Bannu, the

territory is all now subject to British rule, and is steadily becoming

more peaceful and civilized.

Below the Zazis the valley down as far as Waziristan was originally

possessed by the Bangash, a Sunni tribe of Pathans, who came themselves

from the direction of Kohat. The Turis were a Shiah tribe inhabiting

some districts on the eastern bank of the Indus near Kalabagh, who,