The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Draw, by Jerome Bixby This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Draw Author: Jerome Bixby Illustrator: Wm. Ashman Release Date: March 25, 2010 [EBook #31778] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DRAW *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Amazing Stories March 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

THE DRAW

BY JEROME BIXBY

Illustrator: Wm. Ashman

Stories of the old West were filled with bad men who lived by the speed of their gun hand. Well, meet Buck Tarrant, who could outdraw them all. His secret: he didn't even have to reach for his weapon....

oe Doolin's my name. Cowhand—work for old Farrel over at Lazy F beyond the Pass. Never had much of anything exciting happen to me—just punched cows and lit up on payday—until the day I happened to ride through the Pass on my way to town and saw young Buck Tarrant's draw.

Now, Buck'd always been a damn good shot. Once he got his gun in his hand he could put a bullet right where he wanted it up to twenty paces, and within an inch of his aim up to a hundred feet. But Lord God, he couldn't draw to save his life—I'd seen him a couple of times before in the Pass, trying to. He'd face a tree and go into a crouch, and I'd know he was pretending the tree was Billy the Kid or somebody, and then he'd slap leather—and his clumsy hand would wallop his gunbutt, he'd yank like hell, his old Peacemaker would come staggering out of his holster like a bear in heat, and finally he'd line on his target and plug it dead center. But the whole business took about a second and a half, and by the time he'd ever finished his fumbling in a real fight, Billy the Kid or Sheriff Ben Randolph over in town or even me, Joe Doolin, could have cut him in half.

So this time, when I was riding along through the Pass, I saw Buck upslope from me under the trees, and I just grinned and didn't pay too much attention.

He stood facing an old elm tree, and I could see he'd tacked a playing card about four feet up the trunk, about where a man's heart would be.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw him go into his gunman's crouch. He was about sixty feet away from me, and, like I said, I wasn't paying much mind to him.

I heard the shot, flat down the rocky slope that separated us. I grinned again, picturing that fumbly draw of his, the wild slap at leather, the gun coming out drunklike, maybe even him dropping it—I'd seen him do that once or twice.

It got me to thinking about him, as I rode closer.

He was a bad one. Nobody said any different than that. Just bad. He was a bony runt of about eighteen, with bulging eyes and a wide mouth that was always turned down at the corners. He got his nickname Buck because he had buck teeth, not because he was heap man. He was some handy with his fists, and he liked to pick ruckuses with kids he was sure he could lick. But the tipoff on Buck is that he'd bleat like a two-day calf to get out of mixing with somebody he was scared of—which meant somebody his own size or bigger. He'd jaw his way out of it, or just turn and slink away with his tail along his belly. His dad had died a couple years before, and he lived with his ma on a small ranch out near the Pass. The place was falling to pieces, because Buck wouldn't lift a hand to do any work around—his ma just couldn't handle him at all. Fences were down, and the yard was all weedgrown, and the house needed some repairs—but all Buck ever did was hang around town, trying to rub up against some of the tough customers who drank in the Once Again Saloon, or else he'd ride up and lie around under the trees along the top of the Pass and just think—or, like he was today, he'd practise drawing and throwing down on trees and rocks.

Guess he always wanted to be tough. Really tough. He tried to walk with tough men, and, as we found out later, just about all he ever thought about while he was lying around was how he could be tougher than the next two guys. Maybe you've known characters like that—for some damfool reason they just got to be able to whup anybody who comes along, and they feel low and mean when they can't, as if the size of a man's fist was the size of the man.

So that's Buck Tarrant—a halfsized, poisonous, no-good kid who wanted to be a hardcase.

But he'd never be, not in a million years. That's what made it funny—and kind of pitiful too. There wasn't no real strength in him, only a scared hate. It takes guts as well as speed to be tough with a gun, and Buck was just a nasty little rat of a kid who'd probably always counterpunch his way through life when he punched at all. He'd kite for cover if you lifted a lip.

I heard another shot, and looked up the slope. I was near enough now to see that the card he was shooting at was a ten of diamonds—and that he was plugging the pips one by one. Always could shoot, like I said.

Then he heard me coming, and whirled away from the tree, his gun holstered, his hand held out in front of him like he must have imagined Hickock or somebody held it when he was ready to draw.

I stopped my horse about ten feet away and just stared at him. He looked real funny in his baggy old levis and dirty checkered shirt and that big gun low on his hip, and me knowing he couldn't handle it worth a damn.

"Who you trying to scare, Buck?" I said. I looked him up and down and snickered. "You look about as dangerous as a sheepherder's wife."

"And you're a son of a bitch," he said.

I stiffened and shoved out my jaw. "Watch that, runt, or I'll get off and put my foot in your mouth and pull you on like a boot!"

"Will you now," he said nastily, "you son of a bitch?"

And he drew on me ... and I goddam near fell backwards off my saddle!

I swear, I hadn't even seen his hand move, he'd drawn so fast! That gun just practically appeared in his hand!

"Will you now?" he said again, and the bore of his gun looked like a greased gate to hell.

I sat in my saddle scared spitless, wondering if this was when I was going to die. I moved my hands out away from my body, and tried to look friendlylike—actually, I'd never tangled with Buck, just razzed him a little now and then like everybody did; and I couldn't see much reason why he'd want to kill me.

But the expression on his face was full of gloating, full of wildness, full of damn-you recklessness—exactly the expression you'd look to find on a kid like Buck who suddenly found out he was the deadliest gunman alive.

And that's just what he was, believe me.

Once I saw Bat Masterson draw—and he was right up there with the very best. Could draw and shoot accurately in maybe half a second or so—you could hardly see his hand move; you just heard the slap of hand on gunbutt, and a split-second later the shot. It takes a lot of practise to be able to get a gun out and on target in that space of time, and that's what makes gunmen. Practise, and a knack to begin with. And, I guess, the yen to be a gunman, like Buck Tarrant'd always had.

When I saw Masterson draw against Jeff Steward in Abilene, it was that way—slap, crash, and Steward was three-eyed. Just a blur of motion.

But when Buck Tarrant drew on me, right now in the Pass, I didn't see any motion atall. He just crouched, and then his gun was on me. Must have done it in a millionth of a second, if a second has millionths.

It was the fastest draw I'd ever seen. It was, I reckoned, the fastest draw anybody's ever seen. It was an impossibly fast draw—a man's hand just couldn't move to his holster that fast, and grab and drag a heavy Peacemaker up in a two foot arc that fast.

It was plain damn impossible—but there it was.

And there I was.

I didn't say a word. I just sat and thought about things, and my horse wandered a little farther up the slope and then stopped to chomp grass. All the time, Buck Tarrant was standing there, poised, that wild gloating look in his eyes, knowing he could kill me anytime and knowing I knew it.

When he spoke, his voice was shaky—it sounded like he wanted to bust out laughing, and not a nice laugh either.

"Nothing to say, Doolin?" he said. "Pretty fast, huh?"

I said, "Yeah, Buck. Pretty fast." And my voice was shaky too, but not because I felt like laughing any.

He spat, eying me arrogantly. The ground rose to where he stood, and our heads were about on a level. But I felt he was looking down.

"Pretty fast!" he sneered. "Faster'n anybody!"

"I reckon it is, at that," I said.

"Know how I do it?"

"No."

"I think, Doolin. I think my gun into my hand. How d'you like that?"

"It's awful fast, Buck."

"I just think, and my gun is there in my hand. Some draw, huh!"

"Sure is."

"You're damn right it is, Doolin. Faster'n anybody!"

I didn't know what his gabbling about "thinking his gun into his hand" meant—at least not then, I didn't—but I sure wasn't minded to question him on it. He looked wild-eyed enough right now to start taking bites out of the nearest tree.

He spat again and looked me up and down. "You know, you can go to hell, Joe Doolin. You're a lousy, God damn, white-livered son of a bitch." He grinned coldly.

Not an insult, I knew now, but a deliberate taunt. I'd broken jaws for a lot less—I'm no runt, and I'm quick enough to hand back crap if some lands on me. But now I wasn't interested.

He saw I was mad, though, and stood waiting.

"You're fast enough, Buck," I said, "so I got no idea of trying you. You want to murder me, I guess I can't stop you—but I ain't drawing. No, sir, that's for sure."

"And a coward to boot," he jeered.

"Maybe," I said. "Put yourself in my place, and ask yourself why in hell I should kill myself?"

"Yellow!" he snarled, looking at me with his bulging eyes full of meanness and confidence.

My shoulders got tight, and it ran down along my gun arm. I never took that from a man before.

"I won't draw," I said. "Reckon I'll move on instead, if you'll let me."

And I picked up my reins, moving my hands real careful-like, and turned my horse around and started down the slope. I could feel his eyes on me, and I was half-waiting for a bullet in the back. But it didn't come. Instead Buck Tarrant called, "Doolin!"

I turned my head. "Yeah?"

He was standing there in the same position. Somehow he reminded me of a crazy, runt wolf—his eyes were almost yellowish, and when he talked he moved his lips too much, mouthing his words, and his big crooked teeth flashed in the sun. I guess all the hankering for toughness in him was coming out—he was acting now like he'd always wanted to—cocky, unafraid, mean—because now he wore a bigger gun than anybody. It showed all over him, like poison coming out of his skin.

"Doolin," he called. "I'll be in town around three this afternoon. Tell Ben Randolph for me that he's a son of a bitch. Tell him he's a dunghead sheriff. Tell him he'd better look me up when I get there, or else get outa town and stay out. You got that?"

"I got it, Buck."

"Call me Mr. Tarrant, you Irish bastard."

"Okay ... Mr. Tarrant," I said, and reached the bottom of the slope and turned my horse along the road through the Pass. About a hundred yards farther on, I hipped around in the saddle and looked back. He was practising again—the crouch, the fantastic draw, the shot.

I rode on toward town, to tell Ben Randolph he'd either have to run or die.

Ben was a lanky, slab-sided Texan who'd come up north on a drive ten years before and liked the Arizona climate and stayed. He was a good sheriff—tough enough to handle most men, and smart enough to handle the rest. Fourteen years of it had kept him lean and fast.

When I told him about Buck, I could see he didn't know whether he was tough or smart or fast enough to get out of this one.

He leaned back in his chair and started to light his pipe, and then stared at the match until it burned his fingers without touching it to the tobacco.

"You sure, Joe?" he said.

"Ben, I saw it four times. At first I just couldn't believe my eyes—but I tell you, he's fast. He's faster'n you or me or Hickock or anybody. God knows where he got it, but he's got the speed."

"But," Ben Randolph said, lighting another match, "it just don't happen that way." His voice was almost mildly complaining. "Not overnight. Gunspeed's something you work on—it comes slow, mighty slow. You know that. How in hell could Buck Tarrant turn into a fire-eating gunslinger in a few days?" He paused and puffed. "You sure, Joe?" he asked again, through a cloud of smoke.

"Yes."

"And he wants me."

"That's what he said."

Ben Randolph sighed. "He's a bad kid, Joe—just a bad kid. If his father hadn't died, I reckon he might have turned out better. But his mother ain't big enough to wallop his butt the way it needs."

"You took his gun away from him a couple times, didn't you, Ben?"

"Yeah. And ran him outa town too, when he got too pestiferous. Told him to get the hell home and help his ma."

"Guess that's why he wants you."

"That. And because I'm sheriff. I'm the biggest gun around here, and he don't want to start at the bottom, not him. He's gonna show the world right away."

"He can do it, Ben."

He sighed again. "I know. If what you say's true, he can sure show me anyhow. Still, I got to take him up on it. You know that. I can't leave town."

I looked at his hand lying on his leg—the fingers were trembling. He curled them into a fist, and the fist trembled.

"You ought to, Ben," I said.

"Of course I ought to," he said, a little savagely. "But I can't. Why, what'd happen to this town if I was to cut and run? Is there anyone else who could handle him? Hell, no."

"A crazy galoot like that," I said slowly, "if he gets too damn nasty, is bound to get kilt." I hesitated. "Even in the back, if he's too good to take from the front."

"Sure," Ben Randolph said. "Sooner or later. But what about meantime?... how many people will he have to kill before somebody gets angry or nervy enough to kill him? That's my job, Joe—to take care of this kind of thing. Those people he'd kill are depending on me to get between him and them. Don't you see?"

I got up. "Sure, Ben, I see. I just wish you didn't."

He let out another mouthful of smoke. "You got any idea what he meant about thinking his gun into his hand?"

"Not the slightest. Some crazy explanation he made up to account for his sudden speed, I reckon."

Another puff. "You figure I'm a dead man, Joe, huh?"

"It looks kind of that way."

"Yeah, it kind of does, don't it?"

At four that afternoon Buck Tarrant came riding into town like he owned it. He sat his battered old saddle like a rajah on an elephant, and he held his right hand low beside his hip in an exaggerated gunman's stance. With his floppy hat over at a cocky angle, and his big eyes and scrawny frame, he'd have looked funny as hell trying to look like a tough hombre—except that he was tough now, and everybody in town knew it because I'd warned them. Otherwise somebody might have jibed him, and the way things were now, that could lead to a sudden grave.

Nobody said a word all along the street as he rode to the hitchrail in front of the Once Again and dismounted. There wasn't many people around to say anything—most everybody was inside, and all you could see of them was a shadow of movement behind a window there, the flutter of a curtain there.

Only a few men sat in chairs along the boardwalks under the porches, or leaned against the porchposts, and they just sort of stared around, looking at Buck for a second and then looking off again if he turned toward them.

I was standing near to where Buck hitched up. He swaggered up the steps of the saloon, his right hand poised, his bulging eyes full of hell.

"You tell him?" he asked.

I nodded. "He'll look you up, like you said."

Buck laughed shortly. "I'll be waiting. I don't like that lanky bastard. I reckon I got some scores to settle with him." He looked at me, and his face twisted into what he thought was a tough snarl. Funny—you could see he really wasn't tough down inside. There wasn't any hard core of confidence and strength. His toughness was in his holster, and all the rest of him was acting to match up to it.

"You know," he said, "I don't like you either, Irish. Maybe I oughta kill you. Hell, why not?"

Now, the only reason I'd stayed out of doors that afternoon was I figured Buck had already had one chance to kill me and hadn't done it, so I must be safe. That's what I figured—he had nothing against me, so I was safe. And I had an idea that maybe, when the showdown came, I might be able to help out Ben Randolph somehow—if anything on God's Earth could help him.

Now, though, I wished to hell I hadn't stayed outside. I wished I was behind one of them windows, looking out at somebody else get told by Buck Tarrant that maybe he oughta kill him.

"But I won't," Buck said, grinning nastily. "Because you done me a favor. You run off and told the sheriff just like I told you—just like the goddam white-livered Irish sheepherder you are. Ain't that so?"

I nodded, my jaw set so hard with anger that the flesh felt stretched.

He waited for me to move against him. When I didn't, he laughed and swaggered to the door of the saloon. "Come on, Irish," he said over his shoulder. "I'll buy you a drink of the best."

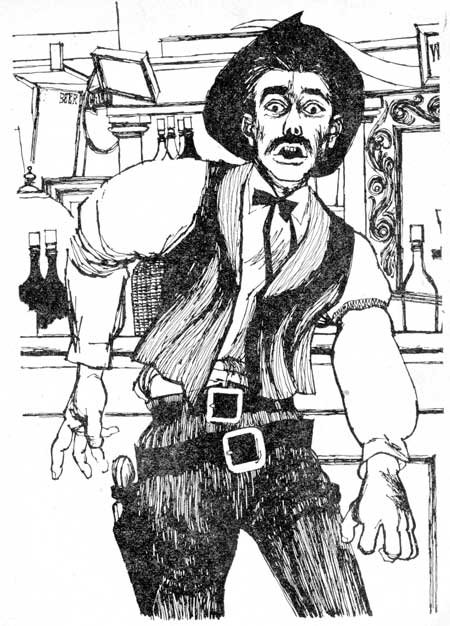

I followed him in, and he went over to the bar, walking heavy, and looked old Menner right in the eye and said, "Give me a bottle of the best stuff you got in the house."

Menner looked at the kid he'd kicked out of his place a dozen times, and his face was white. He reached behind him and got a bottle and put it on the bar.

"Two glasses," said Buck Tarrant.

Menner carefully put two glasses on the bar.

"Clean glasses."

Menner polished two other glasses on his apron and set them down.

"You don't want no money for this likker, do you, Menner?" Buck asked.

"No, sir."

"You'd just take it home and spend it on that fat heifer of a wife you got, and on them two little halfwit brats, wouldn't you?"

Menner nodded.

"Hell, they really ain't worth the trouble, are they?"

"No, sir."

Buck snickered and poured two shots and handed me one. He looked around the saloon and saw that it was almost empty—just Menner behind the bar, and a drunk asleep with his head on his arms at a table near the back, and a little gent in fancy town clothes fingering his drink at a table near the front window and not even looking at us.

"Where is everybody?" he asked Menner.

"Why, sir, I reckon they're home, most of them," Menner said. "It being a hot day and all—"

"Bet it'll get hotter," Buck said, hard.

"Yes, sir."

"I guess they didn't want to really feel the heat, huh?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, it's going to get so hot, you old bastard, that everybody'll feel it. You know that?"

"If you say so, sir."

"It might even get hot for you. Right now even. What do you think of that, huh?"

"I—I—"

"You thrun me outa here a couple times, remember?"

"Y-yes ... but I—"

"Look at this!" Buck said—and his gun was in his hand, and he didn't seem to have moved at all, not an inch. I was looking right at him when he did it—his hand was on the bar, resting beside his shotglass, and then suddenly his gun was in it and pointing right at old Menner's belly.

"You know," Buck said, grinning at how Menner's fear was crawling all over his face, "I can put a bullet right where I want to. Wanta see me do it?"

His gun crashed, and flame leaped across the bar, and the mirror behind the bar had a spiderweb of cracks radiating from a round black hole.

Menner stood there, blood leaking down his neck from a split earlobe.

Buck's gun went off again, and the other earlobe was a red tatter.

And Buck's gun was back in its holster with the same speed it had come out—I just couldn't see his hand move.

"That's enough for now," he told Menner. "This is right good likker, and I guess I got to have somebody around to push it across the bar for me, and you're as good as anybody to do jackass jobs like that."

He didn't ever look at Menner again. The old man leaned back against the shelf behind the bar, trembling, two trickles of red running down his neck and staining his shirt collar—I could see he wanted to touch the places where he'd been shot, to see how bad they were or just to rub at the pain, but he was afraid to raise a hand. He just stood there, looking sick.

Buck was staring at the little man in town clothes, over by the window. The little man had reared back at the shots, and now he was sitting up in his chair, his eyes straight on Buck. The table in front of him was wet where he'd spilled his drink when he'd jumped.

Buck looked at the little guy's fancy clothes and small mustache and grinned. "Come on," he said to me, and picked up his drink and started across the floor. "Find out who the dude is."

He pulled out a chair and sat down—and I saw he was careful to sit facing the front door, and also where he could see out the window.

I pulled out another chair and sat.

"Good shooting, huh?" Buck asked the little guy.

"Yes," said the little guy. "Very fine shooting. I confess, it quite startled me."

Buck laughed harshly. "Startled the old guy too...." He raised his voice. "Ain't that right, Menner? Wasn't you startled?"

"Yes, sir," came Menner's pain-filled voice from the bar.

Buck looked back at the little man—let his insolent gaze travel up and down the fancy waistcoat, the string tie, the sharp face with its mustache and narrow mouth and black eyes. He looked longest at the eyes, because they didn't seem to be scared.

He looked at the little guy, and the little guy looked at Buck, and finally Buck looked away. He tried to look wary as he did it, as if he was just fixing to make sure that nobody was around to sneak-shoot him—but you could see he'd been stared down.

When he looked back at the little guy, he was scowling. "Who're you, mister?" he said. "I never seen you before."

"My name is Jacob Pratt, sir. I'm just traveling through to San Francisco. I'm waiting for the evening stage."

"Drummer?"

"Excuse me?"

For a second Buck's face got ugly. "You heard me, mister. You a drummer?"

"I heard you, young man, but I don't quite understand. Do you mean, am I a musician? A performer upon the drums?"

"No, you goddam fool—I mean, what're you selling? Snake-bite medicine? Likker? Soap?"

"Why—I'm not selling anything. I'm a professor, sir."

"Well, I'll be damned." Buck looked at him a little more carefully. "A perfessor, huh? Of what?"

"Of psychology, sir."

"What's that?"

"It's the study of man's behavior—of the reasons why we act as we do."

Buck laughed again, and it was more of a snarl. "Well, perfessor, you just stick around here then, and I'll show you some real reasons for people acting as they do! From now on, I'm the big reason in this town ... they'll jump when I yell frog, or else!"

His hand was flat on the table in front of him—and suddenly his Peacemaker was in it, pointing at the professor's fourth vest button. "See what I mean huh?"

The little man blinked. "Indeed I do," he said, and stared at the gun as if hypnotized. Funny, though—he still didn't seem scared—just a lot interested.

Sitting there and just listening, I thought about something else funny—how they were both just about of a size, Buck and the professor, and so strong in different ways: with the professor, you felt he was strong inside—a man who knew a lot, about things and about himself—while with Buck it was all on the outside, on the surface: he was just a milksop kid with a deadly sting.

Buck was still looking at the professor, as carefully as he had before. He seemed to hesitate for a second, his mouth twisting. Then he said, "You're an eddicated man, ain't you? I mean, you studied a lot. Ain't that right?"

"Yes, I suppose it is."

"Well...." Again Buck seemed to hesitate. The gun in his hand lowered until the end of the barrel rested on the table. "Look," he said slowly, "maybe you can tell me how in hell...."

When he didn't go on, the professor said, "Yes?"

"Nothing."

"You were going to say—?"

Buck looked at him, his bulging eyes narrowed, the gunman's smirk on his lips again. "Are you telling me what's true and what ain't," he said softly, "with my gun on you?"

"Does the gun change anything?"

Buck tapped the heavy barrel on the table. "I say it changes a hell of a lot of things." Tap went the barrel. "You wanta argue?"

"Not with the gun," the professor said calmly. "It always wins. I'll talk with you, however, if you'll talk with your mouth instead of with the gun."

By this time I was filled with admiration for the professor's guts, and fear that he'd get a bullet in them ... I was all set to duck, in case Buck should lose his temper and start throwing lead.

But suddenly Buck's gun was back in his holster. I saw the professor blink again in astonishment.

"You know," Buck said, grinning loosely, "you got a lotta nerve, professor. Maybe you can tell me what I wanta know."

He didn't look at the little man while he talked—he was glancing around, being "wary" again. And grinning that grin at the same time. You could see he was off-balance—he was acting like everything was going on just like he wanted it; but actually the professor had beaten him again, words against the gun, eyes against eyes.

The professor's dark eyes were level on Buck's right now. "What is it you want to know?"

"This—" Buck said, and his gun was in his hand again, and it was the first time when he did it that his face stayed sober and kind of stupid-looking, his normal expression, instead of getting wild and dangerous. "How—do you know how do I do it?"

"Well," the professor said, "suppose you give me your answer first, if you have one. It might be the right one."

"I—" Buck shook his head—"Well, it's like I think the gun into my hand. It happened the first time this morning. I was standing out in the Pass where I always practise drawing, and I was wishing I could draw faster'n anybody who ever lived—I was wishing I could just get my gun outa leather in no time atall. And—" the gun was back in his holster in the blink of an eye—"that's how it happened. My gun was in my hand. Just like that. I didn't even reach for it—I was just getting set to draw, and had my hand out in front of me ... and my gun was in my hand before I knew what'd happened. God, I was so surprised I almost fell over!"

"I see," said the professor slowly. "You think it into your hand?"

"Yeah, kind of."

"Would you do it now, please?" And the professor leaned forward so he could see Buck's holster, eyes intent.

Buck's gun appeared in his hand.

The professor let out a long breath. "Now think it back into its holster."

It was there.

"You did not move your arm either time," said the professor.

"That's right," said Buck.

"The gun was just suddenly in your hand instead of in your holster. And then it was back in the holster."

"Right."

"Telekinesis," said the professor, almost reverently.

"Telewhat?"

"Telekinesis—the moving of material objects by mental force." The professor leaned back and studied the holstered gun. "It must be that. I hardly dared think if at first—the first time you did it. But the thought did occur to me. And now I'm virtually certain!"

"How do you say it?"

"T-e-l-e-k-i-n-e-s-i-s."

"Well, how do I do it?"

"I can't answer that. Nobody knows. It's been the subject of many experiments, and there are many reported happenings—but I've never heard of any instance even remotely as impressive as this." The professor leaned across the table again. "Can you do it with other things, young man?"

"What other things?"

"That bottle on the bar, for example."

"Never tried."

"Try."

Buck stared at the bottle.

It wavered. Just a little. Rocked, and settled back.

Buck stared harder, eyes bulging.

The bottle shivered. That was all.

"Hell," Buck said. "I can't seem to—to get ahold of it with my mind, like I can with my gun."

"Try moving this glass on the table," the professor said, "It's smaller, and closer."

Buck stared at the glass. It moved a fraction of an inch across the tabletop. No more.

Buck snarled like a dog and swatted the glass with his hand, knocking it halfway across the room.

"Possibly," the professor said, after a moment, "you can do it with your gun because you want to so very badly. The strength of your desire releases—or creates—whatever psychic forces are necessary to perform the act." He paused, looking thoughtful. "Young man, suppose you try to transport your gun to—say, to the top of the bar."

"Why?" Buck asked suspiciously.

"I want to see whether distance is a factor where the gun is concerned. Whether you can place the gun that far away from you, or whether the power operates only when you want your gun in your hand."

"No," Buck said in an ugly voice. "Damn if I will. I'd maybe get my gun over, there and not be able to get it back, and then you'd jump me—the two of you. I ain't minded to experiment around too much, thank you."

"All right," the professor said, as if he didn't care. "The suggestion was purely in the scientific spirit—"

"Sure," said Buck. "Sure. Just don't get any more scientific, or I'll experiment on how many holes you can get in you before you die."

The professor sat back in his chair and looked Buck right in the eye. After a second, Buck looked away, scowling.

Me, I hadn't said a word the whole while, and I wasn't talking now.

"Wonder where that goddam yellow-bellied sheriff is?" Buck said. He looked out the window, then glanced sharply at me. "He said he'd come, huh?"

"Yeah." When I was asked, I'd talk.

We sat in silence for a few moments.

The professor said, "Young man, you wouldn't care to come with me to San Francisco, would you? I and my colleagues would be very grateful for the opportunity to investigate this strange gift of yours—we would even be willing to pay you for your time and—"

Buck laughed. "Why, hell, I reckon I got bigger ideas'n that, mister! Real big ideas. There's no man alive I can't beat with a gun! I'm going to take Billy the Kid ... Hickock ... all of them! I'm going to get myself a rep bigger'n all theirs put together. Why, when I walk into a saloon, they'll hand me likker. I walk into a bank, they'll give me the place. No lawman from Canada to Mexico will even stay in the same town with me! Hell, what could you give me, you goddam little dude?"

The professor shrugged. "Nothing that would satisfy you."

"That's right." Suddenly Buck stiffened, looking out the window. He got up, his bulging blue eyes staring down at us. "Randolph's coming down the street! You two just stay put, and maybe—just maybe—I'll let you live. Professor, I wanta talk to you some more about this telekinesis stuff. Maybe I can get even faster than I am, or control my bullets better at long range. So you be here, get that?"

He turned and walked out the door.

The professor said, "He's not sane."

"Nutty as a locoed steer," I said. "Been that way for a long time. An ugly shrimp who hates everything—and now he's in the saddle holding the reins, and some people are due to get rode down." I looked curiously at him. "Look, professor—this telekinesis stuff—is all that on the level?"

"Absolutely."

"He just thinks his gun into his hand?"

"Exactly."

"Faster than anyone could ever draw it?"

"Inconceivably faster. The time element is almost non-existent."

I got up, feeling worse than I'd ever felt in my life. "Come on," I said. "Let's see what happens."

As if there was any doubt about what was bound to happen.

We stepped out onto the porch and over to the rail. Behind us, I heard Menner come out too. I looked over my shoulder. He'd wrapped a towel around his head. Blood was leaking through it. He was looking at Buck, hating him clear through.

The street was deserted except for Buck standing about twenty feet away, and, at the far end, Sheriff Ben Randolph coming slowly toward him, putting one foot ahead of the other in the dust.

A few men were standing on porches, pressed back against the walls, mostly near doors. Nobody was sitting now—they were ready to groundhog if lead started flying wild.

"God damn it," I said in a low, savage voice. "Ben's too good a man to get kilt this way. By a punk kid with some crazy psychowhosis way of handling a gun."

I felt the professor's level eyes on me, and turned to look at him.

"Why," he said, "doesn't a group of you get together and face him down? Ten guns against his one. He'd have to surrender."

"No, he wouldn't," I said. "That ain't the way it works. He'd just dare any of us to be the first to try and stop him—and none of us would take him up on it. A group like that don't mean anything—it'd be each man against Buck Tarrant, and none of us good enough."

"I see," the professor said softly.

"God...." I clenched my fists so hard they hurt. "I wish we could think his gun right back into the holster or something!"

Ben and Buck were about forty feet apart now. Ben was coming on steadily, his hand over his gunbutt. He was a good man with a gun, Ben—nobody around these parts had dared tackle him for a long time. But he was out-classed now, and he knew it. I guess he was just hoping that Buck's first shot or two wouldn't kill him, and that he could place a good one himself before Buck let loose any more.

But Buck was a damn good shot. He just wouldn't miss.

The professor was staring at Buck with a strange look in his eyes.

"He should be stopped," he said.

"Stop him, then," I said sourly.

"After all," he mused, "if the ability to perform telekinesis lies dormant in all of us, and is released by strong faith and desire to accomplish something that can be accomplished only by that means—then our desire to stop him might be able to counter his desire to—"

"Damn you and your big words," I said bitterly.

"It was your idea," the professor said, still looking at Buck. "What you said about thinking his gun back into its holster—after all, we are two to his one—"

I turned around and stared at him, really hearing him for the first time. "Yeah, that's right—I said that! My God ... do you think we could do it?"

"We can try," he said. "We know it can be done, and evidently that is nine-tenths of the battle. He can do it, so we should be able to. We must want him not to more than he wants to."

"Lord," I said, "I want him not to, all right...."

Ben and Buck were about twenty feet apart now, and Ben stopped.

His voice was tired when he said, "Any time, Buck."

"You're a hell of a sheriff," Buck sneered. "You're a no-good bastard."

"Cuss me out," Ben said. "Don't hurt me none. I'll be ready when you start talking with guns."

"I'm ready now, beanpole," Buck grinned. "You draw first, huh?"

"Think of his gun!" the professor said in a fierce whisper. "Try to grab it with your mind—break his aim—pull it away from him—you know it can be done! Think, think—"

Ben Randolph had never in anyone's knowledge drawn first against a man. But now he did, and I guess nobody could blame him.

He slapped leather, his face already dead—and Buck's Peacemaker was in his hand—

And me and the professor were standing like statues on the porch of the Once Again, thinking at that gun, glaring at it, fists clenched, our breath rasping in our throats.

The gun appeared in Buck's hand, and wobbled just as he slipped hammer. The bullet sprayed dust at Ben's feet.

Ben's gun was halfway out.

Buck's gunbarrel pointed down at the ground, and he was trying to lift it so hard his hand got white. He drove a bullet into the dust at his own feet, and started to whine.

Ben's gun was up and aiming.

Buck shot himself in the foot.

Then Ben shot him once in the right elbow, once in the right shoulder. Buck screamed and dropped his gun and threw out his arms, and Ben, who was a thorough man, put a bullet through his right hand, and another one on top of it.

Buck sat in the dust and flapped blood all around, and bawled when we came to get him.

The professor and I told Ben Randolph what had happened, and nobody else. I think he believed us.

Buck spent two weeks in the town jail, and then a year in the state pen for pulling on Randolph, and nobody's seen him now for six years. Don't know what happened to him, or care much. I reckon he's working as a cowhand someplace—anyway, he sends his mother money now and then, so he must have tamed down some and growed up some too.

While he was in the town jail, the professor talked to him a lot—the professor delayed his trip just to do it.

One night he told me, "Tarrant can't do anything like that again. Not at all, even with his left hand. The gunfight destroyed his faith in his ability to do it—or most of it, anyway. And I finished the job, I guess, asking all my questions. I guess you can't think too much about that sort of thing."

The professor went on to San Francisco, where he's doing some interesting experiments. Or trying to. Because he has the memory of what happened that day—but, like Buck Tarrant, not the ability to do anything like that any more. He wrote me a couple times, and it seems that ever since that time he's been absolutely unable to do any telekinesis. He's tried a thousand times and can't even move a feather.

So he figures it was really me alone who saved Ben's life and stopped Buck in his tracks.

I wonder. Maybe the professor just knows too much not to be some skeptical, even with what he saw. Maybe the way he looks at things and tries to find reasons for them gets in the way of his faith.

Anyway, he wants me to come to San Francisco and get experimented on. Maybe someday I will. Might be fun, if I can find time off from my job.

I got a lot of faith, you see. What I see, I believe. And when Ben retired last year, I took over his job as sheriff—because I'm the fastest man with a gun in these parts. Or, actually, in the world. Probably if I wasn't the peaceable type, I'd be famous or something.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Draw, by Jerome Bixby

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DRAW ***

***** This file should be named 31778-h.htm or 31778-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/3/1/7/7/31778/

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.