The Project Gutenberg EBook of What Need of Man?, by Harold Calin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: What Need of Man? Author: Harold Calin Illustrator: Summers Release Date: January 6, 2010 [EBook #30867] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT NEED OF MAN? *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Amazing Stories, February, 1961. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Bannister was a rocket scientist. He started with the premise of testing man's reaction to space probes under actual conditions; but now he was just testing space probes—and man was a necessary evil to contend with.

hen you are out in a clear night in summer, the sky looks very warm and friendly. The moon is a big pleasant place where it may not be so humid as where you are, and it is lighter than anything you've ever seen. That's the way it is in summer. You never think about space being "out there". It's all one big wonderful thing, and you can never really fall off, or have anything bad happen to you. There is just that much more to see. You lie on the grass and look at the sky long enough and you fall into sort of a detached mood. It's suddenly as if you're looking down at the sky and you're lying on a ceiling by some reverse process of gravitation, and everything is absolutely pleasant.

In winter it's quite another thing, of course. That's because the sky never looks warm. In winter, if you are in a cold climate, the sky doesn't appear at all friendly. It's beautiful, mind you, but never friendly. That is when you see it as it really is. Summer has a way of making it look friendly. The way you see it on a winter night is only the merest idea of what it is really like. That's why I can't feel too bad about the monkey. You see, it might have been a man, maybe me. I've been out there, too.

There are two types of classified government information. One is the type that is really classified because it is concerned with efforts and events that are of true importance and go beyond public evaluation. Occasional unauthorized reports on this type of information, within the scope that I knew it at least, are written off as unidentified flying objects or such. The second type of classified information is the kind that somehow always gets into the newspapers all over the world ... like the X-15, and Project Dyna-Soar ... and Project Argus.

Project Argus had as its basis a theory that was proven completely unsound six years ago. It was proven unsound by Dennis Lynds. He got killed doing it. It had to do with return vehicles from capsules traveling at escape velocity, being oriented and controlled completely by telemetering devices. It didn't work. This time, the monkey was used for newspaper consumption. I'm sure Bannister would have preferred it if the monkey had been killed on contact. It would have been simpler that way. No mass hysteria about torturing a poor, ignorant beast. A simple scientific sacrifice, already dead upon announcement, would have been a fait accompli, so to speak, and nothing could overshadow the success of Project Argus.

But Project Argus was a failure. Maybe someday you'll understand why.

Because of the monkey? Possibly. You see, I flew the second shot after Lynds got killed. After that, came the hearing, and after that no men flew in Bannister's ships anymore. They proved Lynds nuts, and got rid of me, but nobody would try it, even with manual controls, where there is no atmosphere.

When you're putting down after a maximum velocity flight, you feed a set of landing coordinates into the computer, and you wait for the computer to punch out a landing configuration and the controls set themselves and lock into pattern. Then you just sit there. I haven't yet met a pilot who didn't begin to sweat at that moment, and sweat all the way down. We weren't geared for that kind of flying. We still aren't, for that matter. We had always done it ourselves, (even on instruments, we interpreted their meaning to the controls ourselves) and we didn't like it. We had good reason. The telemetry circuits were no good. That's a bad part of a truly classified operation: they don't have to be too careful, there aren't any voters to offend. About the circuits, sometimes they worked, sometimes not. That was the way it went. They wouldn't put manual controls in for us.

It wasn't that they regarded man with too little faith, and electronic equipment with too much. They just didn't regard man at all. They looked upon scientific reason and technology as completely infallible. Nothing is infallible. Not their controls, not their vehicles, and not their blasted egos.

Lynds was assigned the first flight at escape velocity. They could not be dissuaded from the belief that at ultimate speed, a pilot operating manual controls was completely ineffectual. Like kids that have to run electric trains all by themselves, playing God with a transformer. That was when I asked them why bother with a pilot altogether. They talked about the whole point being a test of man's ability to survive; they'd deal with control in proper order. They didn't believe it, and neither did we. We all got very peculiar feelings about the whole business after that. The position on controls was made pretty final by Bannister.

"There will be no manuals in my ships," he said. "It would negate the primary purpose of this project. We must ascertain the successful completion of escape and return by completely automatic operation."

"How about emergency controls?" I asked. "With a switch-off from automatic if they should fail."

"They will not fail. Any manual controls would be inoperative by the pilot in any case. No more questions."

I feel the way I do about the monkey, Argus, because, in a way, we all quit about that time. You don't like having spent your life in a rather devoted way with purposes and all that, and then being placed in the hands of a collection of technologists like just so many white mice ... or monkeys, if you will. Lynds, of course, had little choice. The project was cleared and the assignment set. He hated it well enough, I know, but it was his place to perform the only way one does.

It ended the way we knew it would. I heard it all. It wasn't gruesome, as you might imagine. I spoke with Lynds the whole time. It was sort of a resigned horror. The initial countdown went off without a hitch and the hissing of the escape valves on the carrier rocket changed to a sound that hammered the sky apart as it lifted off the pad.

"Well, she's off," somebody said.

"Let's don't count chickens," Bannister said tautly. Wellington G. Bannister worked for the Germans on V-2s. He is the chief executive of technology in the section to which we were assigned at that time. He is the world's leading expert on exotic fuel rocket projectile systems, rocket design, and a brilliant electronic engineer as well. High enough subordinates call him Wellie. Pilots always called him Professor Bannister. I issued the report that was read in closed session in London in which I accused Bannister of murdering Lynds. That's how come I'm here now. I was cashiered out, just short of a general court martial. That's one of the nice parts about truly classified work. They can't make you out an idiot in public. Living on a boat in the Mediterranean is far nicer than looking up at the earth through a porthole in a smashed up ship on the moon, you must admit.

Well, Bannister could have well counted chickens on that launching. The first, second and third stages fired off perfectly, and within fourteen minutes the capsule detached into orbit just under escape velocity. The orbit was enormously far out. They let Lynds complete a single orbit, then fired the capsule's rockets. He ran off tangential to orbit at escape velocity on a pattern that would probably run in a straight path to infinity. In fact, the capsule is probably still on its way, and as I said, it's six years now. After four minutes, the return vehicle was activated and as it broke away from the capsule, Lynds blacked out for twenty seconds. That was the only time I was out of direct contact with him after he went into orbit.

"Now do you understand about the manual controls?" Bannister said.

"He'll come out of it in less than a minute."

"One can never be sure."

"There's still no reason why you can't use duplicate control systems."

"With a switch-off on the automatic, if they fail?"

"Yes. If for nothing more than to give a man a chance to save his own neck."

"They won't fail."

"The simplest things fail, Bannister. Campbell was killed in a far less elaborate way."

He looked at me. "Campbell? Oh, yes. The landing over the reef. I had nothing to do with that."

"You designed the power shut-off that failed."

"Improper servicing. A simple mechanical failure."

"Or the inability of a mechanism to compensate. The wind shifted after computer coordination. A pilot can feel it. Your instruments can't. There was no failure, there. The shut-off worked perfectly and Campbell was killed because of it."

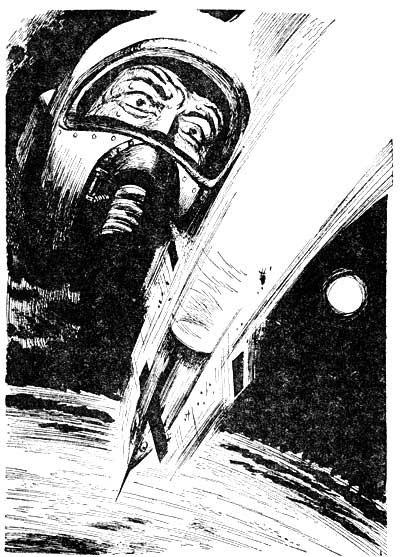

I watched the tracking screen, listened to the high keening noises coming from the receivers. The computers clicked rapidly, feeding out triangulated data on the positions of the escape vehicle and the capsule. The capsule had been diverted from its path slightly by reaction to the vehicle's ejection. Its speed, however, was increasing as it moved farther out. The vehicle with Lynds was in a path parabolic to the capsule, almost like the start of an orbit, but at a fantastic distance. He was, of course, traveling at escape velocity or better, and you do not orbit at escape velocity.

"Harry. Harry, how long was I out?" We heard Lynds' voice come alive suddenly through the crackling static.

"Hello, Dennis. Listen to me. How are you?"

"I'm fine, Harry. What's wrong? How long was I out?"

"Nothing is wrong. You were out less than half a minute. The ejection gear worked perfectly."

"That's good." The tension left his voice and he settled back to a checking and rechecking of instruments, reactions and what he would see. They activated the scanner. The transmitting equipment brought us a view that was little more than a spotty blackness. But I think the equipment was not working properly. You see, what Lynds said did not quite match what we saw. They later used the recording of his voice together with an affidavit sworn to by a technician that our receiver was operating perfectly, as evidence in my hearing. They proved, in their own way, that Lynds had suffered continual delirium after blacking out. The speed, they said, was the cause. It became known as Danger V. Nobody ever bothered to explain why I never encountered the phenomenon of Danger V. It became official record, and my experience was the deviant. It was Bannister's alibi.

We watched the spotty blackness on the screen and listened to Lynds.

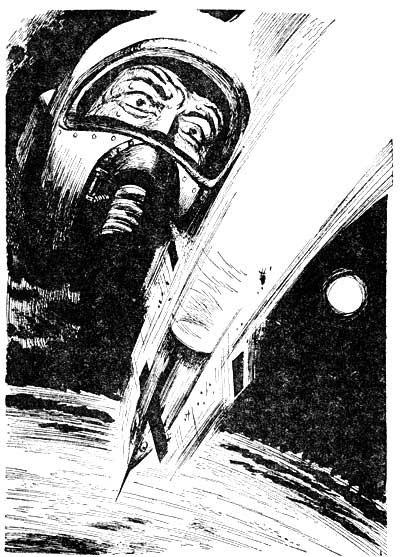

"Harry, I can see it all pretty well now," he began. "There's slight spin on this bomb so it comes and goes. About sixty second revolutions. Nice and slow. Terribly nauseating to look at. But I'm feeling fine now, better than fine. Give me a stick and I'll move the Earth. Who was it said that? Clever fellow. You say I was out about half a minute. That makes it about three more minutes until Bannister's controls are supposed to bring me back."

"Yes, Dennis, but what do you see? Do you hear me? What do you see?"

"Let me tell you something, Harry," he said. "They aren't going to work. They're not wrecked or anything. I just know they aren't worth sweet damn all. Like when Campbell had it. He knew it was going to happen. You can trust the machines just so long. After that, you're batty to lay anything on them at all. But can you see the screen? There it is again. We're turning into view. I can see the earth now. The whole of it."

There was silence then. We looked at the screen but saw only the spotty blackness. I looked from the screen to the speaker overhead, then back at the screen. I looked about the control room. Everyone was doing his work. The instruments all were working. The computers were clicking and nobody looked particularly alarmed, except one other pilot who was there too, Forrest. Maybe Forrest and I pictured ourselves in Lynds' place. Maybe we both had the same premonitions. Maybe we both held the same dislike and distrust of the rest of them. Maybe a lot of things, but one thing was sure. The papers would never get hold of this story, and because of that, Bannister and the rest of them didn't really care a hang about Lynds or me or Forrest or any of the others that might be up there.

It seemed an age passed until we heard Lynds again. The tape later showed it was no more than half a minute. "Bannister, can you hear me?" he said suddenly. "Bannister, do you know what it feels like to be tied into a barrel and tossed over Victoria Falls? Do you? That's what it's like out here. Not that you care a damn. You'll never come up here, you're smart enough for that. Give me a paddle, Bannister, that's what I want. It's no more than a man in a barrel deserves. It's black out here, black and there's nothing to stand on. The earth looks like a flat circle of light and very big, but it doesn't make me feel any better. These buggies of yours won't be any use to anybody until you let the pilot do his own work. I crashed once, in a Gypsy Moth, with my controls all shot away by an overenthusiastic Russian fighter pilot near the Turkish border. Coming down, I felt the way I do now.

"Look at the instruments and remember, Bannister. My reflexes are perfect. There's nothing wrong with me. I could split rails with an axe now, if I had an axe. An axe or a paddle. Harry, I'm not getting back down in one piece. Somehow, I know it. Don't you let them do it to anyone else unless there are manual controls from the ejection onwards. Don't do it. This isn't just nosing into the Slot, over the reef between the town and the island and letting go then, and beginning to sweat. This is much more, Harry. This is bloody frightening. Are the three minutes up yet? My stomach is crawling at the thought of you pushing that button and nothing happening. Listen, Bannister, you're not getting me down, so forget any assurances. I hope they never let you put anybody else up here like this. It's black again. We've swung away."

Bannister looked at my eyes. "It's almost time," he said.

Eight seconds later they pushed the button. Perhaps it would have been better if nothing happened then. But that part worked. They got him out of the parabolic curve and headed back down. They fired reverse rockets that slowed him. They threw him into a broad equatorial orbit and let him ride. It took over an hour to be sure he was in orbit. I admired them that, but began to hate them very much. They ascertained the orbit and began new calculations. Here was where he should have had the controls on in.

The escape vehicle was a small delta shaped craft. The wings, if one could call them that, spanned just under seven feet. They planned to bring him down in a pattern based on very orthodox principles of flight. There remained sufficient fuel for a twelve second burst of power. This would decelerate the craft to a point where it would drop from orbit and begin a descent. I later utilized the same pattern by letting down easy into the atmosphere after the power ran down and sort of bouncing off the upper layers several times to further decelerate and finally gliding down through it at about Mach 5, decelerating rapidly then, almost too rapidly, and finally passing through the exosphere into the ionosphere. The true stratosphere begins between sixty and seventy miles up, and once you've passed through that level and not burnt up, the rest of it is with the pilot and his craft.

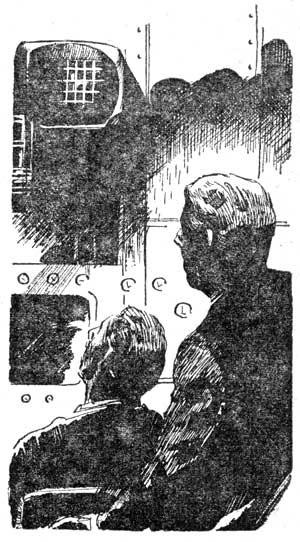

It takes hours. I came down gradually, approaching within striking distance west of Australia, then finally nosed in and took my chance on stretching it to one of the ten mile strips for a powerless landing. I did it in Australia. But if I had not had orthodox controls, had I even gotten that far, I would have churned up a good part of the Coral Sea between Sydney and New Zealand. You see, you've got to feel your way down through all that. That's the better part of flying, the "feel" of it. Automatic controls don't possess that particular human element. And let me tell you, no matter what they call it now—space probing, astronautics or what have you—it's still flying. And it's still men that will have to do it, escape velocity or no. Like they talk about push-button wars, but they keep training infantry and basing grand strategy on the infantry penetration tactics all down through the history of warfare. They call Clausewitz obsolete today, but they still learn him very thoroughly. I once discussed it with Bannister. He didn't like Clausewitz. Perhaps because Clausewitz was a German before they became Nazis. Clausewitz would not look too kindly on a commander whose concern with a battle precluded his concern for his men. He valued men very highly. They were the greatest instrument then. They still are today. That's why I can't really make too much out of the monkey. I feel pretty rotten about him and all that. But the monkey up there means a man someplace is still down here.

Anyway, after Lynds completed six orbital revolutions, they began the deceleration and descent. The whole affair, as I said, was very solidly based on technical determinations of stresses, heat limits, patterns of glide, and Bannister's absolute conviction that nothing would let go. The bitter part was that it let go just short of where Lynds might have made it. He was through the bad part of it, the primary and secondary decelerations, the stretches where you think if you don't fry from the heat, the ship will melt apart under you, and the buffeting in the upper levels when ionospheric resistance really starts to take hold. And believe me, the buffeting that you know about, when you approach Mach 1 in an after-burnered machine, is a piece of cake to the buffeting at Mach 5 in a rocket when you hit the atmosphere, any level of atmosphere. The meteorites that strike our atmosphere don't just burn up, we know that now. They also get knocked to bits. And they're solid iron.

Lynds was about seventy miles up, his velocity down to a point or two over Mach 2, in level flight heading east over the south Atlantic. From about that altitude, manual controls are essential, not just to make one feel better, but because you really need them. The automated controls did not have any tolerance. You don't understand, do you? Look, when one flies and wants to alter direction, one applies pressure to the control surfaces, altering their positions, redirecting the flow of air over the wings, the rudder and so forth. Now, in applying pressure, you occasionally have to ease up or perhaps press a bit more, as the case may be, to counteract turbulence, shift in air current, or any of a million other circumstances that can occur. That all depends on touch. It's what makes some flyers live longer than others. It's like the drag on a fishing reel. You set it tight or loose according to the weight of the fish you're playing. When you reel in, the line can't become too tight or it will snap, so you have the drag. It's really quite ingenious. It lets the fish pull out line as you reel in. It's the degree of tolerance that makes it work well as an instrument. In flying, the degree of tolerance, the compensating factor is in man's hands. In the atmosphere, it's too unpredictable for any other way.

Well, they calculated to set the dive brakes at twelve degrees at the point where Lynds was. Lynds saw it all.

"This is more like my cup of tea," he said at that point. "Harry, the sky is a strange kind of purple black up here."

"They're going to activate the brakes, Den," I said. "What's it like?"

"Not yet, Harry. Not yet."

I looked at Bannister. He noted the chart, his finger under a line of calculations.

"The precise rate of speed and the exact instant of calculation, Captain Jackson," Bannister said. "Would you care to question anything further."

"He said not yet," I told him.

"Therefore you would say not yet?"

"I would say this. He's about in the stratosphere. He knows where he is now. He's one of the finest pilots in the world. He'll feel the right moment better than your instruments."

"Ridiculous. Fourteen seconds. Stand by."

"Wait," I said.

"And if we wait, where does he come down, I ask you? You cannot calculate haphazardly, by feel. There are only four points at which the landing can be made. It must be now."

I flipped the communications switch, still looking at Bannister.

"This is it, Den. They're coming out now."

"Yes, I see them. What are they set for?"

"Twelve degrees."

"I'm dropping like a stone, Harry. Tell them to ease up on the brake. Bannister, do you hear me? Bring them in or they'll tear off. This is not flying, anymore." His voice sounded as if he was having difficulty breathing.

"Harry," he called.

They held the brakes at twelve degrees, of course. The calculations dictated that. They tore away in fifteen seconds.

"Bannister! They're gone," Dennis shouted. "They're gone, Bannister, you butcher. Now what do you say?"

Bannister's face didn't flinch. He watched the controls steadily.

"Try half-degree rudder in either direction," I said.

Bannister looked at me for a second. "His direction is vertical, Captain. Would you attempt a rudder manipulation in a vertical dive?"

"Not a terminal velocity drive, Bannister. He said it's not flying anymore. Lord knows which way he's falling."

"So?"

"So I'd try anything. You've got to slow him."

"Or return him to level flight."

"At this speed?"

We both looked at the controls now. The ship was accelerating again, and dropping so rapidly I couldn't follow the revolutions counter.

"Engage the ailerons," Bannister ordered. "Point seven degrees, negative."

Dennis came back on. "Harry, what are you doing? The ship is falling apart. The ailerons. It won't help. Listen, Harry, you've got to be careful. The flight configuration is so tenuous, anything can turn this thing into a falling stone. It had to happen, I knew, but I don't want to believe it now. This sitting here with that noise getting louder. It's spiraling out at me, getting bigger. Now it's smaller again. I'm afraid, Harry. The ailerons, Harry, they're gone. Very tenuous. They're gone. I can't see anything. The screens are black. No more shaking. No more noise. It's quiet and I hear myself breathing, Harry. Harry, the wrist straps on the suits are too tight. And the helmet, when you want to scratch your face, you can go mad. And Harry—"

That was the end of the communications. Something in the transmitter must have gone. They never found out. He didn't hit until almost a minute later, and nobody ever saw it. The tracking screen followed him down very precisely and very silently. There was no retrieving anything, of course. You don't conduct salvage operations in the middle of the south Atlantic.

I turned in my report after that. No one had asked for it, so it went through unorthodox channels. It took an awfully long time and my suspension did not become effective until after the second shot. I was the pilot on that one, you know. I got them to install the duplicate controls, over the insistence by Bannister that resorting to them, even in the event that it became necessary, would prove nothing. He even went as far as to talk about load redistribution electric control design. As a matter of fact, I thought he had me for a while, but I think in the end they decided to try to avoid the waste of another vehicle. At least, that might be the kind of argument that would carry weight. The vehicles were enormously expensive, you realize.

I made it all right, as I said. It took me nine hours and then some, once they dropped me from orbit. I switched off the automatic controls at the point where the dive brakes were to have been engaged. This time, the brakes had not responded to the auto controls and they did not open at all. I found out readily enough why Lynds was against opening them at that point. Metal fatigue had brought the ship to a point where even a shift in my position could cause it to stop flying.

I came down in Australia and the braking 'chute tore right out when I released it. I skidded nine miles. A Royal Australian Air Force helicopter picked me up two hours later.

I learned of the suspension while in the hospital. I didn't get out until just in time to get to London for the hearing. My evidence and Forrest's, and Lynds' recorded voice all served to no purpose. You don't become a hero by proving an expert wrong. It doesn't work that way. It would not do to have Bannister looked upon as a bad gambit, not after all they went through to stay in power after putting him in. The reason, after all, was all in the way you looked at it. And a human element could always be overlooked in the cause of human endeavor. Especially when the constituents never find out about it.

After that, they started experimentation with powered returns. The atmosphere has been conquered, and now there remained the last stage. They never did it successfully. They couldn't. But it did not really matter. What it all proved was that they did not really need pilots for what Bannister was after. He had started with a premise of testing man's reactions to space probes under actual conditions, but what he was actually doing was testing space probes alone, with man as a necessary evil to contend with to give the project a reason.

It was all like putting a man in a racing car traveling flat out on the Salts in Bonneville, Utah. He'll survive, of course. But put the man in the car with no controls for him to operate and then run the thing completely through remote transmission, and you've eliminated the purpose for the man. Survival as an afterthought might be a thing to test, if you didn't care a hoot about man. Survival for its own sake doesn't mean anything unless I've missed the whole point of living, somewhere along the line.

Bannister once described to me the firing of a prototype V-2. The firing took place after sunset. When the rocket had achieved a certain altitude, it suddenly took on a brilliant yellow glow. It had passed beyond the shadow of the earth and risen into the sunlight. Here was Bannister's passion. He was out to establish the feasibility of putting a rocket vehicle on the moon. It could have a man in it, or a monkey. Both were just as useless. Neither could fly the thing back, even if it did get down in one piece. It could tell us nothing about the moon we didn't already know. Getting it down in one piece, of course, was the reason why they gave Bannister the project to begin with.

So Bannister is now a triumphant hero, despite the societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals. But nobody understood it. Bannister put a vehicle on the moon. We were the first to do it. We proved something by doing nothing. Perhaps the situation of true classified information is not too healthy a one, at that. You see, we've had rockets with that kind of power for an awfully long time now. Maybe some of them know what he's up to. When I think about that, I really become frightened.

The monkey, I suppose, is dead. The most we can hope for is that he died fast. It's very like another kind of miserable hope I felt once, a long time ago, for a lot of people who could be offered little more than hope for a fast death, because of something somebody was trying to prove. There's some consolation this time. It's really only a monkey.

This I know, they'll never publish a picture of the vehicle. Someone might start to wonder why the cabin seems equipped to carry a man.

When you're out in a clear night in summer, the sky looks very friendly, the moon a big pleasant place where nothing at all can happen to you. The vehicle used in Project Argus had a porthole. I can't imagine why. The monkey must have been able to see out the porthole. Did he notice, I wonder, whether the earth looks friendly from out there.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of What Need of Man?, by Harold Calin

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT NEED OF MAN? ***

***** This file should be named 30867-h.htm or 30867-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/0/8/6/30867/

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.