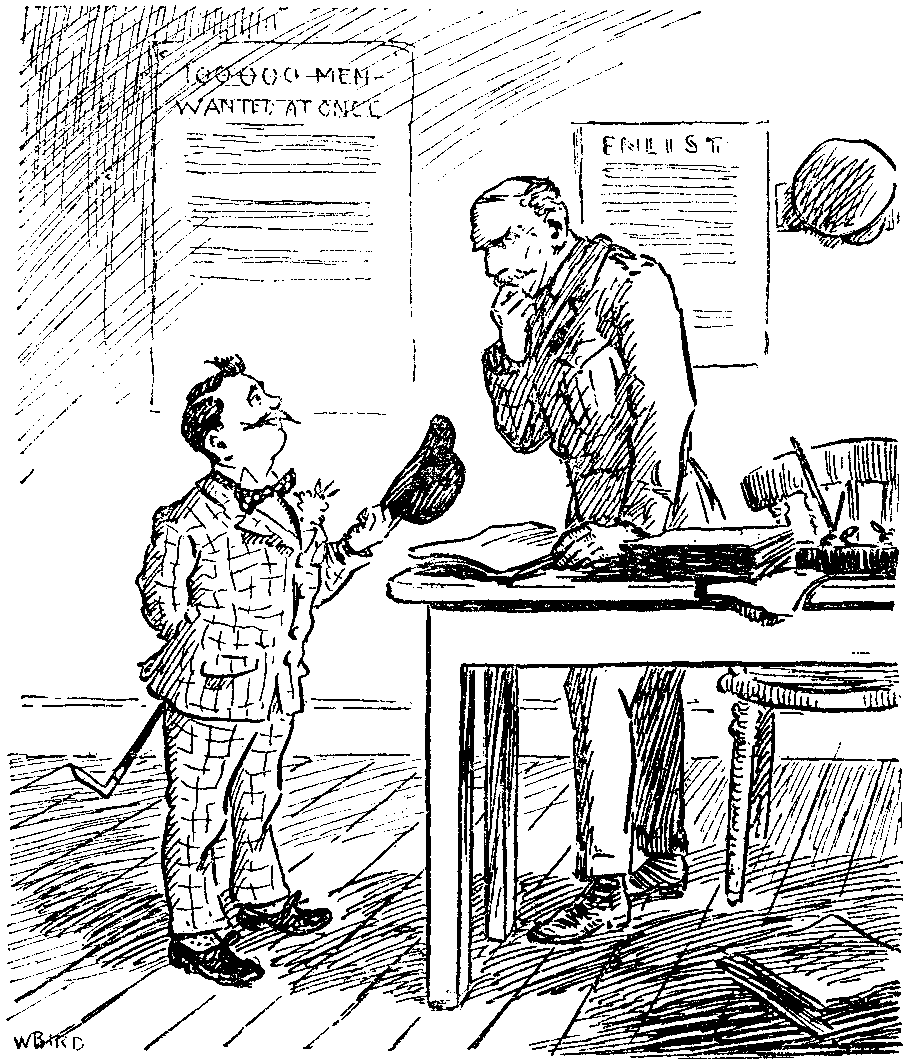

"But you aren't tall enough."

"Well, can I go as a drummer-boy?"

"I'm afraid you're too old for that."

"Well, then—dash it all! I'll go as a mascot."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 147, December 30, 1914, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 147, December 30, 1914 Author: Various Editor: Owen Seaman Release Date: August 11, 2009 [EBook #29669] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Malcolm Farmer, Katherine Ward, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Abdul the D—d is said to feel it keenly that, when the British decided to appoint a Sultan in Egypt, they did not remember that he was out of a job.

Meanwhile Abbas Pasha is reported to have had a presentiment that he would one day be replaced by Kamel Pasha. It is said that for some time past he would start nervously whenever he heard the band of a Highland regiment playing "The Kamel's a-coming."

We have very little doubt that the German newspapers are publishing photographs of Whitby Abbey, and claiming the entire credit for its ruined condition.

It remained for The Times to chronicle the Germans' most astounding feat. It happened at Hartlepool. "A chimney nearly 200 feet in height, on the North-Eastern Railway hydraulic power-station, was," our contemporary tells us, "grazed by a projectile about 100 yards above its base."

The Archbishop of York, who was one of the Kaiser's few apologists, is said to feel keenly that potentate's ingratitude in selecting for bombardment two unprotected bathing-places in his Grace's diocese.

It is widely rumoured that Wilhelm is conferring a special medal on the perpetrators of this and similar outrages, to be called the Kaiser-ye-Hun medal.

Some of the German newspapers have been organising a symposium on the subject of how to spend the coming Christmas. Herr Arthur von Gwinner, director of the Deutsche Bank, is evidently something of a humourist. "More than ever," he says, "in the exercise of works of love and charity." We rather doubt whether the Herr Direktor's irony will be appreciated in high quarters.

A message from Amsterdam says that there are signs in Berlin of discontent with the German Chancellor and his staff, and patriots are calling for a "clean sweep." The difficulty, of course, is that, while there are plenty of sweeps in Germany, it is not easy to find a clean one.

"Immediately after his arrival at Rome," says The Liverpool Echo, "Prince Buelow proceeded to the Villa Malte, his usual residence at Rome, where he will stay until he takes up his quarters at the Caffarelli police." Our alleged harsh treatment of aliens fades into insignificance by the side of this!

General Baron von Bissing, the Governor-General of Belgium, has informed a German journal that the Kaiser has "very specially commanded him to help the weak and oppressed in Belgium." By whom, we wonder, are the Belgians being oppressed?

The same journal announces that General von Diedenhofen, the commander at Karlsruhe, has issued a proclamation expressing his "indignation at the dishonourable conduct" of three German Red-Cross Nurses who have married wounded French prisoners. It certainly does look like taking advantage of the poor fellows when they were more or less helpless.

We hear that considerable ill-feeling has been caused in certain quarters of Paris by a thoughtless English newspaper calling the Germans "the Apaches of Europe."

A German critic has been expatiating on the trouble we must have in feeding an Army with so many different tastes and creeds. Commenting on this, The Evening Standard says: "This is not a surprising matter from our point of view, but the German cast-iron system does not lend itself either in thought or practice to adaptability." Some people, we believe, imagine the Germans feed, without exception, on Pickelhauben.

A little while ago the Germans were claiming our Shakspeare. We now hear that a forthcoming production at His Majesty's Theatre has set them longing, in view of the scarcity of the metal, for our Copperfield.

Mr. Thomas Burt, M.P., Father of the House of Commons, has decided to resign his seat in Parliament. This does not however mean that the House will be left an orphan. Another father will be found at once.

It is rumoured that, after the War is over, a statue is to be erected to the Censor at Blankenberghe, in Belgium.

A tale from the Front. "The enemy are continuing to fortify the coast, Sir," said the subaltern. "I don't care if they fiftify it," roared his commanding officer; "it'll make no difference." This shows the British spirit.

"But you aren't tall enough."

"Well, can I go as a drummer-boy?"

"I'm afraid you're too old for that."

"Well, then—dash it all! I'll go as a mascot."

"General Smuts stated that there were in the field at the present time, not including those training, more than —— men."—Daily Telegraph.

This is headed "South Africa's Forces," and may have been an actual piece of news until it reached the Censor.

We read beneath a photograph in The Graphic:—

"Miss Pauline Prim—the cat in the Aldwych Pantomime, as she is in real life."

From a recent Geography Examination paper:—

"Holland is a low country: in fact it is such a very low country that it is no wonder that it is damned all round."

A correspondent writes:—

"It is to be hoped that nothing further will be heard of these various proposals to intern the Kaiser at St. Helena. One would have thought that there had been quite sufficient desecration already of places of historic interest."

Kaiser, what vigil will you keep to-night?

Before the altar will you lay again

Your "shining armour," and renew your plight

To wear it ever clean of stain?

Or, while your priesthood chants the Hymn of Hate,

Like incense will you lift to God your breath

In praise that you are privileged by fate

To do His little ones to death?

Will Brother Henry, knowing well the scene

That saw your cruisers' latest gallant feat,

Kneel at your side, and ask with pious mien

A special blessing on the fleet?

Will you make "resolutions?"—saying, "Lo!

I will be humble. Though my own bright sword

Has shattered Belgium, yet will I bestow

The credit on a higher Lord.

"What am I but His minister of doom?

The smoke of burning temples shall ascend,

With none to intercept the savoury fume,

Straight upward to my honoured Friend."

Or does your heart admit, in hours like these,

God is not mocked with words; His judgment stands;

Nor all the waters of His cleansing seas

Can wash the blood-guilt from your hands?

Make your account with Him as best you can.

What other hope has this New Year to give?

For outraged earth has laid on you a ban

Not to be lifted while you live.

(From the Ex-Sultan Of Turkey.)

My Brother,—There are many who in these days gnash their teeth against you and pursue with malice and reproach the words you utter and the deeds you perform, so that verily the tempests of the world beat about your head. It may please you, therefore, to know that there is one man at least whose affectionate admiration for you has suffered no decrease, nay, has rather been augmented a hundredfold by the events of the past half-year. Need I say that I am that man?

It is true that I have been shorn of my honours and privileges, that I live in exile as a prisoner and that the vile insulters of fallen majesty compass me about. I who once dwelt in splendour and issued my commands to the legions of the faithful am treated with contumely by a filthy pack of time-servers, and have nothing that I can call my own except, for the moment, the air that I breathe. Oh, for an hour of the old liberty and power! It would amuse me to see the faces of Enver and of my wretched brother Mohammed as I ordered them to execution—them and their gang of villainous parasites. By the bowstring of my fathers, but that would be a great and worthy killing! Pardon the fond day-dreams of a poor and lonely old man whose only crime has been that he loved his country too well and treated his enemies with a kindness not to be understood by those black and revengeful hearts.

I remember that in the old days there were not wanting those who warned me against you. "Beware," they said, "of the German Emperor. He will use you for his own purposes, and will then cast you aside like an orange that has been squeezed." But I paid no heed to their jealous imaginings, and I had my reward. Not, indeed, that you were able to save me when the wicked burst upon me and cast me down. The stroke was too sudden, and you, alas, were too far. But the memory of our delightful friendship is still with me to sustain and comfort me in my tribulations. I still have some of the letters in which you poured out your heart to me, and when melancholy oppresses me I take them from my breast and read them over and over again.

It is a joy to me to know that there is a firm alliance between my brave Turks and your magnanimous soldiers. I doubt not that Allah, the good old friend of the Turks, will continue to bless you and give you victory after victory over your enemies. It is no less a joy to learn how gloriously and how sagaciously you are conducting this war. They tell me that your ships have bombarded the coast towns of England, and that five or six hundred of the inhabitants have fallen before your avenging shells. What matters it that these towns were not fortified in the strict and stupid sense, and that there were many women and children amongst those you slew? The towns were fortified in the sense that they were hostile to your high benevolence, and as for women and children you need not even dream of excusing yourself to me. These English are no better than Armenians. It is necessary to extirpate them, and the younger you catch them the less time they have for devising wickedness against the Chosen of Allah. As for women, they need hardly be taken into account. In all these matters I know by your actions that you agree. You must proceed on your noble course until the last of these infidels is swept away to perdition.

May I condole with you on the loss of your four ships of war by the guns of the British Admiral Sturdee? That was, indeed, a cowardly blow, and it is hard to understand why it was allowed.

Farewell then, my Brother. Be assured again of the undying friendship and admiration of the poor exile,

[Reports continue to reach us from our brave troops in the field that they "never felt fitter," are "in the best of spirits," and so forth.]

Have you a bronchial cough, or cold,

And is your ailment chronic

Past every sort of cure that's sold?

We'll tell you of a tonic.

Just wing our agents here a wire

And book "A Fortnight Under Teuton Fire."

Do you admit with anxious mind

Your liver's loss of movement,

And that in consequence you find

Your temper needs improvement?

Then leave awhile your stool or bench

And try our "Month Inside a Flooded Trench."

Are you a broken nervous wreck,

Run short of red corpuscles,

Painfully scraggy in the neck,

And much in need of muscles?

Come to us now—for now's your chance—

And take our "Lively Tour Through Northern France."

There is an impression about that among the candidates for the position of real hero of the war King Albert might have a chance; or even Lord Kitchener or Sir John French. But I have my doubts, after all that I have heard—and I love to hear it and to watch the different ways in which the tellers narrate it: some so frankly proud, some just as proud, but trying to conceal their pride. After all that I have heard I am bound to believe that for the real hero of the war we must look elsewhere. Not much is printed of this young fellow's deeds; one gets them chiefly by word of mouth and very largely in club smoking-rooms. In railway carriages too, and at dinner-parties. These are the places where the champions most do congregate and hold forth. And from what they say he is a most gallant and worthy warrior. Versatile as well, for not only does he fight and bag his Bosch, but he is wounded and imprisoned. Sometimes he rides a motor cycle, sometimes he flies, sometimes he has charge of a gun, sometimes he is doing Red Cross work, and again he helps to bring up the supplies with the A.S.C. He has been everywhere. He was at Mons and he was at Cambrai. He marched into Ypres and is rather angry when the Germans are blamed for shelling the Cloth Hall, because he tells you that there was a big French gun firmly established behind it, and only by shelling the building could the enemy hope to destroy that dangerous piece of ordnance. He saw something of the bombardment of Rheims and he watched the monitors at work on the Belgian coast.

And not only does he perform some of the best deeds and often get rewarded for them, but he is a good medium for news too. He hears things. He's somewhere about when General —— says something of the deepest significance to General ——. He knows men high up in the War Office. He refers lightly to Kitchener, and staff officers apparently tell him many of their secrets. He speaks quite casually and familiarly of Winston and what Winston said yesterday, for he often has the latest Admiralty news too. It was he who had the luck to be in the passage when Lord Fisher and another Sea Lord executed their historic waltz on the receipt of the news of Sturdee's coup. I don't pretend that he is always as worthy of credence as he was then; for he has spread some false rumours too. He was, in fact, one of the busiest eye-witnesses (once or twice removed) of the triumphant progress of millions of Russians through Scotland and England some months ago. He is not unaware of the loss of battleships of which nothing has yet been officially stated. In fact, his unofficial news is terrific and sometimes must be taken with salt. But denials do not much abash him. He was prepared for them and can explain them.

His letters are interesting and cover a vast amount of ground. They are sometimes very well written, and in differing moods he abuses the enemy and pities them. He never grumbles but is sometimes perplexed by overwork in the trenches. He hates having to stand long in water and has lost more comrades than he likes to think about. One day he was quite close to General Joffre, whom he regards as a sagacious leader, cautious and far-sighted; another day he was close to Sir John French, and nothing could exceed the confidence which his appearance kindled in him. On the morning of the King's arrival at the Front he was puzzled by the evolutions of our air scouts, who seemed to have gone mad; but it turned out that they were saluting His Majesty. Some of his last letters were from the neighbourhood of Auchy and described the fighting for the canal. He is a little inconsistent now and then, and one day says he has more cigarettes than he can smoke, and the next bewails the steady shortage of tobacco. As to his heroic actions he is reticent; but we know that many of the finest deeds have been performed by him. He has saved lives and guns and is in sight of the V.C.

And what is his name? Well, I can't say what his name is, because it is not always the same; but I can tell you how he is always described by those who relate his adventures, his prowess, his news, his suspicions and his fears. He is always referred to as "My son."

"My son," when all is said, is the real hero of the war.

It is all very well to warn the British public (naturalised or otherwise) against supporting and comforting the enemy, but it might have more effect if those in authority set the example.

"The British Government declares that in the event of the Austrian Government being in need of funds, Great Britain is ready to provide them."—Japan Chronicle.

"King George has sent a warmly-worded telegram of congratulation to the new Sultan of Turkey."—Sunday Chronicle.

Paragraphs such as these, for instance, do not provide the proper inspiration.

"There are increasing rumours of serious fiction between the Austrians and the Germans."—Natal Times.

Their forte, however, is humorous fiction.

Over the hills where the grey hills rise

Smoke wreaths climb to the cloudless skies,

White in the glare of the noonday sun,

Climbing in companies, one by one,

From the strong guns,

The long guns,

That wake with break of day

And dutifully drop their shells a dozen miles away.

Far beneath where our airmen fly,

Slowly the Garrison guns go by,

Breaking through bramble and thorn and gorse,

Towed by engines or dragged by horse,

The great guns,

The late guns,

That slowly rumble up

To enable Messrs. Vickers to converse with Messrs. Krupp.

Garrison cannon is never swift

(Shells are a deuce of a weight to lift);

When they are ready to open shop,

Where they are planted, there they stop,

The grey guns,

The gay guns,

That know what they're about,

To wait at fifteen hundred yards and clear the trenches out.

4.7's and 9.4's,

Taking to camping out of doors;

Out of the shelter of steel-built sheds,

Sleeping out in their concrete beds—

The proud guns,

The loud guns,

Whose echo wakes the hills,

And shakes the tiles and scatters glass on distant window-sills.

Little cannon of envious mind

May mock at the gunners who come behind;

Let them wait till we've lined our pets

On to the forts and the walls of Metz;

The siege guns,

The liege guns,

The guns to batter down

The barricades and bastions of any German town.

Though there be others who do good work,

Harassing German, trouncing Turk,

Let us but honour one toast to-day—

The men and the guns of the R.G.A.!

The vast guns,

The last guns,

When Spring is coming in,

To roll down every Eastern road a-booming to Berlin!

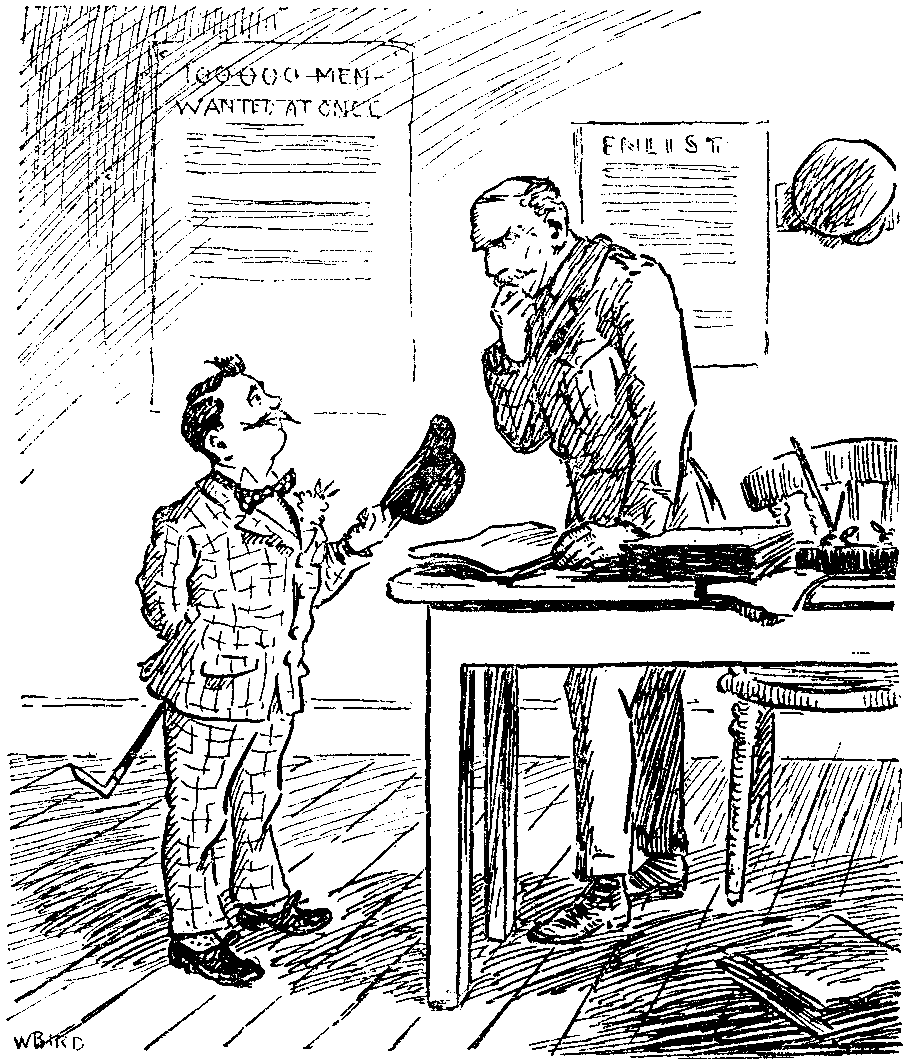

Fond Mother (who has just seen her son, a very youthful subaltern, off to the front). "I got him away from his father for a moment and said to him, 'Darling, don't go too near the firing-line, will you?'"

The Strategist's Muzzle.—For use in the Home—the Club—the Railway Train. Fitted with best calf leather gag—easily attached—efficiency guaranteed, 4s. 11d. With chloroform attachment for violent cases, 8s. 11d. Belloc size, 22s. 6d.

Recommended by the Censor.

The Allies' Musical Box.—Beautifully decorated in all the national colours. A boon to organizers of war concerts. Plays all the National Anthems of the Allies simultaneously, thus allowing the audience to keep their seats for the bulk of the evening. A blessing to wounded soldiers and rheumatic subjects. 10s. 11d. carriage paid.

The Coin Detector.—This ingenious little contrivance rings a bell once when brought within a yard of silver coins and twice when in the proximity of gold coins. Absolutely indispensable to collectors for Relief Funds. 2s. 11½d. post free.

Testimonial from Lady Isobel Tompkins:—

"Since using your invaluable detector in my collecting work I understand that there has been quite a run on the banks and post-offices in this neighbourhood for postal orders and the new notes. With the addition of an indicator of paper-money your machine would be perfection."

Happy Families.—The game of the season—with portraits of all our political leaders. Any four assorted leaders of different views make a happy family. 10½d.

Mr. Keir Hardie says:—"I never knew a more aggravating game."

German Happy Families.—Intensely amusing; peals of laughter come from the table when one asks for Mr. Kayser, the butcher; Mr. Prince, the looter; Mr. Tirpitz, the pirate, 10½d.

Burke's Norman Blood.—The presentation book of the season. Invaluable to the newly naturalised. 3s. 6d. net.

From certain Regimental Orders we extract the following:—

"There is no objection to the following being written on the Field Service Post Card: 'A merry Christmas and a happy New Year.'"

All the same, the danger of conveying news to the enemy must not be overlooked. Many German soldiers, we hear, are under the impression that it is still August, and that they will be in Paris by the beginning of September.

"In the early hours of Wednesday morning, what is supposed to have been a traction engine when proceeding southward, struck the west side of the parapet with great force."—Alnwick Gazette.

When proceeding northward it has more the appearance of a sewing-machine.

My dear Charles,—I write on Christmas Day from a second-grade Infants' School, the grade referring obviously to the school and not to the infants. We sit round the old Yule hot-water pipe, and from the next classroom come the heavenly strains of the gramophone, one of those veteran but sturdy machines which none of life's rough usages can completely silence or even shake in its loyal determination to go on and keep on going on at all costs. Having duly impressed "Good King Wenceslas" upon us, it is now rendering an emotional waltz, of which, though now and then it may drop a note or two, it mislays none of the pathos.

It was a present to the Mess; intended for our entertainment in the trenches, though I cannot think who was going to carry it there. The tune serves to recall the distant past, when we used to wear silk socks and shining pumps, to glide hither and thither on hard floors, and talk in the intervals, talk, talk, talk with all the desperate resource of exhausted heroes who know that they have only to hang on five more minutes and they are saved. Suppose we had by now been in those trenches and had been listening to this obstinate old box slowly but confidently assuring and reassuring us that there is and was and always will be our one-two-three home in the one-two-three, one-two-three West! I can see the picture; I can see the tears of happiness coursing down our weather-beaten cheeks as we say to ourselves, "Goodness knows, it's uncomfortable enough here, but thank heaven we aren't in that ball-room anyway."

In a corner of this room is a bridge-four. The C.O. is sitting in an authoritative, relentless silence. His tactical dispositions have been made and they are going to be pushed through to the end, cost what it may to the enemy or his own side. His partner is Second-Lieutenant Combes, deviously thinking to himself with all the superior knowledge of youth, "What rotten dispositions these C.O.'s do make!" but endeavouring to conceal his feelings by the manipulation of his face and a more than usually heavy interspersion of "Sirs" in his conversation. The enemy are ill-assorted allies: Captain Parr, a dashing player of great courage and very ready tongue, and Lieutenant Sumners, one of those grim, earnest fighters whom no event however sudden or stupendous can surprise into speech. This latter is a real soldier whose life is conducted in every particular on the lines laid down in military text-books. He asks himself always, "Is it soldierly?" and never "Is it common-sense?" He is at present in trouble with his superior officer for having frozen on to his ace of trumps long after he should have parted with it. But those text-books say, "Keep your best forces in reserve," and so the little trumps must needs be put in the firing line first.

As to the other officers of your acquaintance, each is making merry, as the season demands, in his own fashion. One is studying, not for the first time, a map on the wall showing the inner truth of the currents in the Pacific; another is observing, for his information and further guidance, the process of manufacture of lead pencils as illustrated by samples in a glass-case. Others are being more jovial still; having exhausted the pictures and advertisements of the sixpenny Society papers, they are now actually reading the letter-press. The machine-gun officer, as I gather from his occasional remarks, is asleep as usual.

And now the gramophone has ceased; but, alas! Captain d'Arcy has begun—on the piano. As I write, the scheme of communication between his right and his left flanks has broken down. Like a prudent officer, he suspends operations, gives the "stand-fast!" and sends out a cautious patrol to reconnoitre the position. He even cedes a little of the ground he has gained. Glancing at his music, I must admit that he is in a dangerous situation, heavily wooded in the treble, with sudden and sharp elevations and depressions in the bass, and the possibility of an ambush at every turn. His reconnoitring party returns; he starts to move forward again with scouts always in advance. He halts; he advances again and proceeds (for he too is a trained soldier) by short rushes about five bars at a time.... At last the situation develops and he pauses to collect all his available forces and get them well in hand. I can almost hear the order being passed along the line—"Prepare to charge"—almost catch the bugle-call as his ten fingers rush forth to the assault, forth to death or glory, to triumph or utter confusion.... As to what follows, I have always thought the rally after a charge was an anticlimax, even when it consists of a rapid "Rule Britannia!" passing off evenly, without a hitch.

I find, looking round my fellow-officers, that I have omitted the final touch, the last stirring detail to complete the picture of the soldier's hard but eventful life. In the one easy, or easy-ish, chair sits the Major, that gallant gentleman whose sole but exacting business in life it is to gallop like the devil into the far distance when it is rumoured that the battalion will deploy. He sits now at leisure, but even at leisure he is not at ease: silent, with every nerve and fibre strained to the utmost tension, he crouches over his work. He is at his darning; ay, with real wool and a real needle he is darning his socks. The colour of his work may not be harmonious, but it is a thorough job; he has done what even few women would do, he has darned not only the hole in his hosiery but his left hand also.

As for the men, they have been dealt with by a select body under the formidable title of the Christmas Festivities Committee. It has provided each man with a little beer, a lot of turkey and much too much plum pudding. Having disengaged the birds into their separate units, it has then left the man to himself for the day, thus showing, in my opinion, a wise discretion rarely found in committees, even military committees.

Yours ever,

Henry.

Visitor. "Could you tell me what time the tide is up?"

Odd job man. "Well, Sir, they do expeck 'igh water at six; but then you know wot these 'ere rumours are nowadays."

"Exchange, charming country parish, North Yorks. Easy distance sea. Income safe."—Advt. in "Guardian."

Yes, but what about the rectory?

I rode into Pincher River on an August afternoon,

The pinto's hoofs on the prairie drumming a drowsy tune,

By the shacks and the Chinks' truck-gardens to the Athabasca saloon.

And a bunch of the boys was standing around by the old Scotch store,

Standing and spitting and swearing by old Macallister's door—

And the name on their lips was Britain—the word that they spoke was War.

War!... Do you think I waited to talk about wrong or right

When I knew my own old country was up to the neck in a fight?

I said, "So long!"—and I beat it—"I'm hitting the trail to-night."

I wasn't long at my packing. I hadn't much time to dress,

And the cash I had at disposal was a ten-spot—more or less;

So I didn't wait for my ticket; I booked by the Hoboes' Express.

I rode the bumpers at night-time; I beat the ties in the day;

Stealing a ride and bumming a ride all of the blooming way,

And—I left the First Contingent drilling at Valcartier!

I didn't cross in a liner (I hadn't my passage by me!);

I spotted a Liverpool cargo tramp, smelly and greasy and grimy,

And they wanted hands for the voyage, and the old man guessed he'd try me.

She kicked like a ballet-dancer or a range-bred bronco mare;

She rolled till her engines rattled; she wallowed, but what did I care?

It was "Go it, my bucking beauty, if only you take me there!"

Then came an autumn morning, grey-blue, windy and clear,

And the fields—the little white houses—green and peaceful and dear,

And the heart inside of me saying, "Take me, Mother, I'm here!

"Here, for I thought you'd want me; I've brought you all that I own—

A lean long lump of a carcass that's mostly muscle and bone,

Six-foot-two in my stockings—weigh-in at fourteen stone.

"Here, and I hope you'll have me; take me for what I'm worth—

A chap that's a bit of a waster, come from the ends of the earth

To fight with the best that's in him for the dear old land of his birth!"

Lady in black. "Our Jim's killed seven Germans—and he'd never killed ANYONE before he went to France!"

The Anonymous War is not to be followed by an Anonymous Peace. I have Twyerley's own authority for this statement.

I may go farther and make public the interesting fact that Twyerley himself has the matter in hand, and readers of The Daily Booster will at an early date receive precise instructions how and where to secure Part I. of The History of the Peace before it is out of print. It is well known that all publications issuing from that Napoleonic brain are out of print within an hour or two of their appearance, but Twyerley takes precautions to safeguard readers of The Booster against any such catastrophic disappointment.

In approaching the Peace problem at this stage Twyerley is displaying his customary foresight. The military authorities frustrated Twyerley's public-spirited attempt to let the readers of The Booster into the secret of General Joffre's strategy—ruthlessly suppressing his daily column on The Position at the Front. He has resolved that the diplomatists shall not repeat the offence; he will be beforehand with them.

If Twyerley had been listened to in times of peace there would have been no war; the fact is undeniable. Since war has come, however, the danger of a patched-up peace must be avoided at all costs. In order that there shall be no mistake Twyerley has prepared a map of Europe-as-it-must-be-and-shall-be or Twyerley and his myriad readers will know the reason why. (The map is presented gratis with Part I. of the History and may also be had, varnished and mounted on rollers, for clubs and military academies.)

Twyerley at work upon the map is a thrilling spectacle. With his remorseless scissors he hovers over Germany and Austria in a way that would make the two Kaisers blench. Snip! away goes Alsace-Lorraine and a slice of the Palatinate; another snip! and Galicia flutters into the arms of Russia.

The History is to be completed in twenty-four parts, if the Allies' plenipotentiaries possess the capabilities with which Twyerley credits them; but he has prudently provided for extensions in case of need.

Anyway, whether the Treaty of Peace be signed in twelve months or twelve years, the final part of the History will go to press on the morrow.

Armed with the History, readers of The Booster will be able to follow step by step the contest in the council-chamber, when it takes place. They will be able to paint the large white map with the special box of colours supplied at a small additional cost. That, as Twyerley justly observes, is an ideal means of teaching the new geography of Europe to children. Even the youngest member of a household where the History is taken regularly will be in a position to say what loss of territory the Kaisers and Turkey must suffer. (Twyerley had some idea of running a Prize Competition on these lines but was reluctant to embarrass the Government.)

Several entire chapters will be devoted to "Famous Scraps of Paper" from Nebuchadnezzar to the Treaty of Bucharest. Illustrations of unique interest have been secured. For instance, the Peace of Westphalia carries a reproduction of the original document, portraits and biographies of the signatories, and a statistical table of the Westphalian ham industry. Similarly, the Treaty of Utrecht is accompanied by a view of that interesting town and several pages of original designs for Utrecht velvet.

Thus, what Twyerley calls "the human interest" is amply catered for.

The section "International Law for the Million" presents its subject in a novel tabloid form, as exhaustive as it is entertaining. I know for a fact that an army of clerks has been engaged at the British Museum for some weeks looking up the data.

Following the part which contains concise accounts of every European nation from the earliest times, comes "Points for Plenipotentiaries," occupying several entire numbers. Here is where the genius of Twyerley shines at its brightest, and personally I think that the British representatives at the Peace Congress should be provided beforehand with these invaluable pages. With Twyerley at their elbows, so to speak, they should be equal to the task of checkmating the wily foreigner.

I wish the Kaiser could see Twyerley scissoring his territory to shreds!

I dislike many things—snakes, for example, and German spies, and the income tax, and cold fat mutton; but even more than any of these I dislike William Smith.

As all the world knows, special constables hunt in couples at nights, a precaution adopted in order that, if either of the two is slain in the execution of his duty, the other may be in a position to report on the following morning the exact hour and manner of his decease, thus satisfying the thirst of the authorities for the latest information, and relieving his departed companion's relatives of further anxiety in regard to his fate.

William Smith is the special constable who hunts with me. As to whom or what we are hunting, or what we should do to them or they would do to us if we caught them or they caught us, we are rather vague; but we endeavour to carry out our duty. Our total bag to date has been one Royal Mail, and even him we merely let off with a caution.

Three days ago, by an unfortunate coincidence, William Smith overtook me at the end of the High Street, just as our sergeant was coming round the corner in the opposite direction. At sight of the latter we halted, dropped our parcels in the mud, stiffened to attention and saluted. The last was a thing we ought not to have done, even allowing for his leggings, which were (and are still) of a distinctly upper-military type. But in the special constabulary your sergeant is a man to be placated. His powers are enormous. He can, if he likes, spoil your beauty sleep at both ends by detailing you for duty from 12 to 4 A.M.; or, on the other hand, he can forget you altogether for a fortnight. Thus we always avoid meeting him if possible; failing that, we always salute him.

"Ha!" exclaimed our sergeant.

We shuddered, and William Smith, who is smaller than myself, tried to escape his gaze by forming two deep.

"What the devil are you playing at?" growled our sergeant. Though one of the more prominent sidesmen at our local church, he has developed quite the manner of an officer, almost, at times, I like to think, of a general officer. William Smith formed single rank again.

Our sergeant took out his notebook. "I'm glad I happened to meet you two," he said.

We shivered, but otherwise remained at attention.

"Let me see," he went on, consulting his list, "you are on together again to-morrow night at 12."

It was the last straw. Forgetting his rank, forgetting his leggings, forgetting the possibilities of his language, forgetting myself, I spoke.

"I protest," I said.

The eyes of our sergeant bulged with wrath, pushing his pince-nez off his nose and causing them to clatter to the pavement. But a special constable is a man of more than ordinary courage. "Allow me," I murmured, and I stooped, picked them up and handed them back to him.

"Explain yourself," he muttered hoarsely.

"For the past three months," I said, "I have endured fifty-six of the darkest hours of the night, cut off from any possibility of human aid, in the company of William Smith, a conversational egoist of the lowest and most determined type. Throughout this period he has inflicted on me atrocities before which those of the Germans pale into insignificance. During the first month he described to me in detail the achievements and diseases from birth upwards of all his children—a revolting record. He next proceeded to deal exhaustively with the construction and working of his gramophone, his bathroom geyser, his patent knife-machine and his vacuum carpet-cleaner; also with his methods of drying wet boots, marking his under-linen, circumventing the water-rate collector and inducing fertility in reluctant pullets. This brought us to the middle of November. Finally, during the last four weeks he has wandered into the ramifications of his wife's early-Victorian family tree, of which we are still in the lower branches.

"I cannot retaliate in kind. I have no children, poultry, pedigree wives, nor any of the other articles, except boots and shirts, in which the soul of William Smith rejoices. There is but one remedy open to me, and of this, unless you detail me for duty with someone else, I propose to avail myself at the first convenient opportunity. I shall kill William Smith."

I stopped and saluted again.

And then a wonderful thing happened. I discovered that beneath our sergeant's military leggings there still beat the rudiments of a human heart. Yes, as I looked at him I saw his softened eyes suffused with sympathetic tears.

"My poor fellow!" he said in a broken voice.

It was too much. I sank to the pavement, saluting as I fell, and knew no more. When I recovered consciousness in hospital I found in the pocket of my coat an envelope containing the following: "Promoted to the rank of corporal and invalided for three weeks, after which you will take duty with your chauffeur."

William Smith and I have severed diplomatic relations. It is better so.

My dear Mr. Punch,—In these first few days after Christmas many of your readers are no doubt faced, as we have been, with a problem which is quite new to them. I hope they took the precaution—as we did—to write and explain to all likely givers (1) that this was no year for the exchange of Christmas gifts among grown-up people who have no need for them; (2) that it was the opinion of all right-thinking persons that no such gifts should be sent, and (3) that consequently they were sending none and hoped to receive none.

That is all right as far as it goes, but the problem remains of what is to be done with those people who can't be stopped? We have had several painful instances of this sort. The stuff has arrived, the usual sort of non-war stuff, some of which must have cost quite a lot of money, of which it may with truth be said, "your King and Country need you." How were these things to be dealt with, since we felt that we could not keep them?

We found that no general treatment could be applied; we have had to sort them out into groups, before deflecting them into the proper courses.

Books to hospitals. In this case the matron is asked to acknowledge them direct to the original giver.

Smoking Accessories (such as the newest pipe-filler and match-striker and cigarette-case-opener and pouch-unfolder [pg 537] and cigar-holder-grip), to the nearest male Belgian; and

All other portable presents to the nearest female Belgian. (These two classes may be neatly acknowledged in the columns of the Courier Belge.)

All larger presents (of the motor-car, pianola and sewing-machine variety) to be sold by auction for the National Relief Fund. Marked catalogue of the sale to be sent to the giver in proof of their safe arrival.

Yours, etc.,

An Ordinary Englishman.

Officer (instructing recruits in signalling). "Didn't you get that message?"

Recruit. "Yes, Sir: 'Three Taubs and a Zeplin comin' over the 'ill.'"

Officer. "Then why the deuce didn't you send it on?"

Recruit. "Well, Sir, I couldn't 'ardly believe it."

"The Surveyor reported that the owners of the manure heaps by the Recreation Ground Tennis Courts had by now been covered over with seaweed, etc., thus complying with the Council's wishes."—Barmouth Advertiser.

We hope this will be a lesson to them.

The usual formula for beginning a letter is thus neatly rendered by a Hottentot Boy:—

"As I have a line to state just to let you know that I am still soluberious under the superiority of the Supreme-Being, hoping to hear the same likewise from you."

We recommend it very heartily as a good opening for New Year's Eve correspondence.

It was a mighty Emperor

Of ancient pedigree

Who said, "The future of our race

Lies on the rolling sea!"

And straightway laboured to fulfil

His royal guarantee.

And when the Day had dawned, for which

He long had toiled and planned,

Unto his Grand High Admiral

He issued his command:

"Go forth, and smite the enemy

Upon his native strand."

Sailing by night and veiled in mist,

His swiftest ships of war

Rained death on two defenceless towns

For half an hour or more,

Till they had slain and wounded babes

And women by the score.

The Fatherland was filled with joy

By this heroic deed;

It gloated o'er the slaughtered babes

Of Albion's hated breed;

And Iron Crosses fell in showers

On those who'd made them bleed.

But honest neutrals everywhere

Were sickened and dismayed;

The Turk, not squeamish as a rule,

No special glee betrayed;

And even Mr. Bernard Shaw

Failed to defend the raid!

Then more in sorrow than in wrath

The Emperor made moan:

"Though martyred and misunderstood

I tread my way alone,

At least I have the sympathy

Of God on His high throne."

Then from the pillar and the cloud

Came accents clear and plain:

"The Massacre of Innocents

Passes the guilt of Cain;

And those who sin with Herod earn

His everlasting stain."

Two announcements at Hereford:—

"Cathedral Service, Sunday, Dec. 13th.

Preacher: Rev. H. M. Spooner.

Baptist Chapel.

Lecture: 'Slips of Speech and Trips in Type.'"

"Yes," said the President of New College on his way to the Cathedral, "I know something about slips of speech, but what are tips in tripe?"

(Extract from a Report by the German Admiral.)

Battle-cruiser "Von Herod."

Sir,—With regard to the recent magnificent and hoch-compelling exploit of the Imperial Squadron I have the honour to report as follows:—

Our battle-cruisers sighted the strongly-fortified sea-coast town of Little Shrimpington about 12.45, and at once opened a devastating fire. A hostile abbey, situated in a commanding position at the cliff top, and quite unmistakable (as at Whitby), was the first to fall. The shelling of this edifice, to which I learn that the Christians attach considerable importance, for some reason that I am unable to comprehend, cannot fail to produce lively satisfaction among our brave allies at Constantinople.

Next turning our guns upon the golf links, in fifteen rounds we put out of action a nine-hole course for ladies. Much confusion was observed here amongst the enemy; the presence of troops being proved by the movement of several bodies in bright scarlet. It is conjectured from this that the supply of khaki is already exhausted.

Magnificent execution was done upon the extensive sand castles with which the foreshore was covered, and for which indeed it is renowned throughout the island. Our heavy armament was in every case enabled to demolish these, at the same time slaughtering the children and nurses responsible for them. It is to be admitted however that at a more favourable season of the year the execution here, good as it was, would have been considerably better.

Altogether some five hundred shells were fired, as recently at Scarborough, and there can be no doubt that the enemy's casualties, in women especially, must be very considerable. In addition, he is known to have lost heavily in bathing-machines, and several super-rowing boats were seen to sink at their moorings.

Throughout the action the entire absence of any return fire had a most heartening effect upon the personnel of the Imperial fleet, who were thus enabled to work under what may be called conditions ideal to the German fighting spirit. I cannot refrain from expressing my sense of how greatly the magnificent result of the action was due to the patriotic foresight of my chief officer, Fire-direktor Von Ketch, who, having met with a motor accident when touring in England so lately as last spring at the gates of Shrimpington Hall, had the good fortune to be the guest for several weeks of the Frau Squire and her daughters. Not only was the information thus obtained of the greatest assistance in the general conduct of the operations, but we were enabled to place our first six-inch shell exactly on the dining-room of the Hall at an hour when the occupants were almost certainly assembled for lunch.

The entire action occupied twenty-five minutes, and concluded with the approach of the British patrol, when, acting in accordance with the dictates of Imperial policy, we ran like hares. So satisfactory has been this glorious and civilian-sanguinary encounter that our brave fellows are now eager to try conclusions with the bath-chairs of Bournemouth or the lobster-pots of Llandudno. It is indeed with true sentiments of fraternal pride that the Imperial Navy is now able to place the torn fragments of the Hague Convention beside those of the Treaties so gloriously deleted by our brothers of the Imperial Army.

I have the honour to be, Sir, etc., etc.

First Urchin (to Captain who has just bought a new motor-horn). "Carry yer parcel, Colonel?"

Second ditto (in a hoarse whisper). "Garn! Can't yer see 'e's a bugler?"

"Note.—A kilometre is, roughly, five-fifths of a mile."—Newcastle Evening Chronicle.

The Press Bureau, while not objecting....

Victorine, our new general, is a Belgian refugee. She was naturally somewhat broken in spirit on first entering our establishment, but as the days went by she became happier, and so enterprising and ingratiating that we hastened to smother in its infancy a shameful doubt as to whether or not we had introduced into our sympathetic bosoms a potential viper. Morning, noon and night there was continuous scrubbing, polishing and beeswaxing; at all moments one was meeting a pink and breathless Victorine, and the house echoed to an interminable stream of information in the French tongue.

At mealtime, the verdict having been duly pronounced on each successive dish, Victorine would stand by while we ate, and unburden herself confidentially. 'Mon mari' (Jean Baptiste, a co-refugee who had searched all London for a place as valet de chambre) was lightly touched upon. Belgium was described in glowing terms, a land of wonders we had not dreamt of.

"Miss will not believe me, but when first we arrive in England all the world cries, 'Oh! regard then the little sheep!' For Mademoiselle must know that in Belgium the sheep are high and big as that" (Victorine sketches in the air the dimensions of a good-sized donkey). "Monsieur mocks himself of me? Monsieur should visit my pays where dwell the sheep of a bigness and a fatness to rejoice the heart, and whose wool is of a softness incredible; Monsieur would not then smile thus in his beard." Victorine assumes an attitude of virtuous indignation, disturbed by the ringing of the telephone bell.

"I save myself," she murmurs.

Through the half-open door we hear as usual only scraps of dialogue, all on one side, and very unsatisfying.

"Alloa! J'écoute! Madame, je ne parle que le français—hein?" Long pause. "Alloa! Alloa!" Victorine rattles the instrument impatiently. "Ah! ça y est! Si Madame désire que j'appelle Miss——? Quel nom? Hein? Meesus Tsch—arch—kott. Mon Dieu——"

Victorine lays down the receiver and comes back flushed into the room.

"C'est Meesus Arch-tsch-kott qui demande Miss au téléphone. She desire to know if Miss will take the dinner with her. Are they difficult these English names!"

But English names are not Victorine's sole difficulty. She wrestles (mentally) from time to time with the butcher and the baker and the milkman. The milkman, it seems, is "un peu fou." Victorine greets him in the mornings in voluble French, and he in return bows elaborately and pretends to drop the milk. We have watched the process from an upper window. Victorine takes a step backward, her hand flies to her heart, and, as she afterwards informs us, "her blood gives but a turn" at this exhibition of British wit. We have been wondering whether it would be judicious to teach her to say, "Get along with yer."

She is very prolific in "ideas," and seems to be chiefly inspired when engaged in the uncongenial pastime of cleaning the grate.

"Know you, Miss, that I have an idea, me?"

"No, really, Victorine."

"Yes," says Victorine, mournfully shaking her head, "but only an idea." Victorine lays down her implements and places her hands on her hips. "If," she says slowly, "this Meesus Schmeet who was with Mr. and Miss before my arrival was a German spy, hein?"

"But why, Victorine?"

Victorine assumes an air of owl-like wisdom.

"See here," she says, placing the forefinger of one hand on the thumb of the other, "first she depart to care for the niece who is suffering—it is generally the mother, but that imports not. Then," counting along her fingers, "during three months she is absent, and, thirdly," sinking her voice, "she sends for her malles, which contain doubtless—who knows?—plans of London, designs of the fortresses, and perhaps a telegraphy without wires—Marconi, what do I know? Mademoiselle must admit that it has the air droll?"

We do our best to allay Victorine's anxiety. She however is not at all convinced, and evidently reserves to herself full liberty of action to protect us from German espionage and the effects of our own guilelessness at a later date.

In the rare moments when not at work she is pensive, but her imagination is by no means at rest. She gazes languidly out of the window into "ce brouillard," as she fondly calls a slight morning mist. The sparrows interest her.

"See, Miss, a sparrow who carries a piece of bread big as a house; is it then an English sparrow that accomplishes such prodigies?"

Not quite fathoming the drift of Victorine's meditations we suggest that it is perhaps a Belgian refugee sparrow, at which her amusement is so intense that she is obliged to leave the room.

Sometimes her fancy takes great flights, for she is very high-minded. Her weekly bath gives rise to much lofty philosophical reflection, and she has come to the firm conclusion that it is "mieux que manger." Also she has great taste, of which she occasionally gives us the benefit. She laughs scornfully at certain objets d'art and praises others. Ornaments, if they meet with her approval, are arranged in rigid lines of continuous beauty, less favoured ones being pushed into the background, and books are disposed with assumed carelessness in thoughtful postures. Though it is plain she thinks little of our taste in general, her disapproval is usually silent. It is therefore with almost choking pride that we receive her praise, though it is often, we fear, of a disingenuous nature.

"It is plain that Miss has the eye artistic: that sees itself well in the new basin she has bought to replace the one that fell by hazard and burst itself. Monsieur also has the eye straight. In effect the picture there that Monsieur designs is of a justness, but of a justness! One would say the place itself," leaning back and half closing her eyes. "In Belgium could it not be better done. No. It is I, Victorine, who say it. If Monsieur has the false digestion, by contrary it is evident that he has the head solid."

But Victorine has a fault dark and grievous in the British eye. She jibs at fresh air.

"Surely Mr., and above all Miss, will take a congestion with the window grand-open of that fashion? As for me I have the neuralgias to make fear! Figure to yourself that in the kitchen the three windows (where one would well suffice, go) if open make to pass a hurricane!"

A short lecture follows, in which the ill effects of stuffiness are pointed out, and Victorine is reduced to unconvinced and mutinous silence. As the days pass a little acquiescence in "cette manie pour les courants d'air" is visible, but at the slightest approach of cold every aperture through which air may possibly find its way is surreptitiously closed, and it is only when she is out with her husband taking a walk or refreshing the inner man in a "café" with "un peu de stoot" that we can penetrate by stealth into her bedroom and air it.

Jean Baptiste is for the moment in disgrace because he has not been to see Victorine for a week. He is threatened with all sorts of penalties when he finally decides to present himself. Primarily Victorine is going to present him with savon, which appears in the vernacular to be the Belgian equivalent for beans. She is also going to wash him the head.

First Old Dame. "Well, my dear, and what are you doing for the country?"

Second ditto. "I am knitting socks for the troops."

First Old Dame (robustly). "Knitting! I am learning to shoot!"

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Sir John Lubbock, whose Life, by Mr. Horace Hutchinson, Macmillan publishes in two volumes, was one of the most honourable men who figured in public life during the last half-century. He was also one of the most widely honoured. Under his name on the title-page of the book appears a prodigious paragraph in small type enumerating the high distinctions bestowed upon him by British and foreign literary and scientific bodies. Forestalling the leisure of a bank-holiday I have counted the list and find it contains no fewer than fifty-two high distinctions, one for every week of the year. These were won not by striking genius or brilliant talent. Sir John Lubbock, to preserve a name which the crowning honour of the peerage did not displace in the public mind, was by nature and daily habit constitutionally industrious. After Eton he joined his father's banking business. In his diary under date Christmas Day, 1852, being the nineteenth year of his age, he gives an account of how he spends his day. It is too long to quote, but, beginning by "getting up at half-past six," it includes steady reading in natural history, poetry, political economy, science, mathematics and German. Breakfast, luncheon and tea are mentioned in due course; but there is no reference to dinner or supper. These functions were doubtless regarded by the young student as frivolous waste of time.

I knew Lubbock personally during his long membership of the House of Commons. He had neither grace of diction nor charm of oratory. But he had a way of getting Bills through all their stages which exceeded the average attained by more attractive speakers. In his references to Parliamentary life he mentions that Gladstone, when he proposed to abolish the Income Tax, told him that he intended to meet the deficiency partly by increase of the death duties. That was a fundamental principle of the Budget Lord Randolph Churchill prepared during his brief Chancellorship of the Exchequer. It was left to Sir William Harcourt to realise the fascinating scheme, later to be extended by Mr. Lloyd George. Another of Lord Randolph's personally unfulfilled schemes was the introduction of one-pound notes. In a letter dated 16th December, 1886, he confidentially communicated his project to Lubbock. When his book reaches its second edition Mr. Hutchinson will have an opportunity of correcting a misapprehension set forth on page 48. He writes that, on June 21st, 1895, "all were startled by an announcement that Mr. Gladstone had resigned and that Parliament was to be dissolved." The surprise was not unnatural since Lord Rosebery was Prime Minister at this memorable crisis.

I can see some good in most people, but none whatever in those chairmen of meetings who, being put up to introduce distinguished speakers, thoroughly well worth listening [pg 544] to, feel called upon to delay matters by making lengthy speeches themselves. I propose to be quite brief in announcing Professor Stephen Leacock on Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich (Lane). Conceive this arch-humourist let loose, if so rough a term may be applied to so delicate a wit, among the sordid and fleshly plutocracy of a progressive American city; imagine his polished satire expending itself on such playful themes as the running of fashionable churches on strictly commercial lines, dogma and ritualism being so directed and adapted as to leave the largest possible dividends on the Special Offertory Cumulative Stock, and your appetite will be whetted for an intellectual feast of the most delicious flavour. For myself, I found a certain quiet but intense delight in the first five stories, episodes in the lives of individual billionaires; but when I came to the last three, which dealt with the class as a collective whole, then I became frankly and noisily hilarious. I am not given to being tiresome in the reading-room; it is another of the unforgivable offences; but I defy any man of intelligence to read those chapters and retain even a fair remnant of self-control.

The Lighter Side of School Life (Foulis) is one of the merriest and shrewdest books that I have met for a long time. Mr. Ian Hay pleasantly dedicates his work "to the members of the most responsible, the least advertised, the worst paid, and the most richly rewarded profession in the world"; and you will not have turned two pages before discovering that the writer of them knows pretty thoroughly what he is writing about. For my own part I claim to have some experience both of schoolmasters and boys, and I can say at once that the former at least have seldom been dealt with more faithfully than by Mr. Hay. His chapter on "Some Form Masters" is a thing of the purest joy; bitingly true, yet withal of a kindly sympathy with his victims. One would say that he knows boys as well, were it not for the conviction that to imagine any kind of understanding of Boydom is (if my contemporaries will forgive me) the last enchantment of the middle-aged, and the most fallacious. As for the Educational experts, he has all the cold and calculated hate for them that is the mark of experience. I admired especially his treatment of the "craze for practical teaching," the theory which holds, for example, that, instead of postulating a fixed relation between the circumference of a circle and its diameter, a teacher should supply his boys with several ordinary tin canisters, a piece of string and a ruler, and leave the form to work out their own result. Decidedly, Mr. Hay has seen The Lighter Side of School Life with the eye of knowledge; and when I mention that your own eyes will here encounter a dozen pictures by Mr. Lewis Baumer at his delightful best—well, I suppose, enough said.

At one time, I hope for ever gone, Mr. Percy White's sense of irony ran away with him. He seemed to have said to himself, "I can write witty dialogue and I have a shrewd eye for foibles, and if you are not satisfied with that you can take it or leave it." I for one took it, but always with a feeling that he was offering me a sparkling wine of a quality not first-rate, whereas with a little more trouble and expense he could have offered me an unimpeachable brand. Now that Cairo (Constable) has provided me with what I have been waiting for, I am more than delighted to present my acknowledgments. Mr. White's subject is pat to the moment; moreover it is handled with such unobtrusive skill that one absorbs a serious problem without being anxiously conscious that all the play of intrigue and adventure is covering a much deeper motive. When Mr. White sent Daniel Addington to Egypt to meet Abdul Sayed, who had been at Oxford and was a leader of the Young Egyptian party, he gave himself a chance of which he has taken full advantage. It is true that Addington cried a pest on all politics as soon as he fell a victim to the charms of Ann Donne, a widow of excessive sprightliness; but by that time he was too deeply enmeshed in the nets of intrigue to escape the just reward of those amateurs who dabble with critical situations. Abdul regarded him as a "milksop," and so he was from Abdul's full-blooded point of view; but I can also see in him a fresh testimony to the courage of our race. For he married the widow Ann, and that was a very plucky thing to do.

The only thing that I didn't like about Molly, My Heart's Delight (Smith, Elder) was the title. But to allow yourself to be put off by this will be to miss one of the pleasantest books of the season. What I might call true fiction has always held a peculiar charm for me. In the present work that clever writer, Katharine Tynan, has been lucky and astute enough to find an ideal heroine, ready made to her hand, in the person of the charming woman who married Dean Delany. Upon the basis of her diaries and letters the romance has been built up, with the excellent result of a blend of art and actuality that is most engaging. Molly is the gayest of creatures in her girlhood. We see her character develop gradually, tamed and half broken by her unhappy first marriage (an episode exquisitely treated, so that even the ugly side of it bears yet some precious jewels of charity and long-suffering), tried in the fire of romantic adoration, and finally reaching its appointed destiny in the comradeship with "kind, tender, faithful D.D." Lovers of diaries and memoirs, equally with those who like a graceful tale well told, will find what they want here, from the moment when its heroine goes, a girl-bride, to the romantically gloomy house of Rhoscrow, to that other moment when the placid mistress of the Deanery hears of the death of Bellamy, the man whom all her life she really loved. This book of Molly should be a "heart's delight" to many.

"ARIZONA BILL VIOLATES TREATIES."—New York Times.

So does Potsdam Bill.

Mr. Punch drew another letter from the heap on his office-desk and opened it.

Polwheedle, Cornwall.

Dear Mr. Punch,—An amusing incident happened here yesterday. I was talking to an old countryman, a great character in the village, and I happened to make some remark about the War. "What war?" asked old Jarge. "The European War," I answered in surprise. "Well," he said, "they've got a fine day for it." I thought this would interest you.

Yours etc.,

John Brown.

"Two hundred and eighteen," said Mr. Punch to himself, and took the next letter from the heap.

Wortleberry, Sussex.

Mr. William Smith presents his compliments to Mr. Punch and begs to send him the following dialogue which occurred in this village yesterday:—

Myself. "Well, what do you think of the War, Jarge?"

Jarge. "What war?"

Myself (surprised). "The European War."

Jarge. "They've got a fine day for it, anyhow."

Mr. Smith thought you would like this.

"Two hundred and nineteen," said Mr. Punch to himself, "not counting the South African or Crimean ones." He sighed and selected a third letter.

Sporransprock, Kirkcudbrightshire.

Dear Mr. Punch,—How's this? I asked a native what he thought of the War. On being told which war, he replied, "Eh, mon, ye ken, but they've got a gran'——"

At this point Mr. Punch rose from his chair and began to pace the room restlessly.

"There must be more in life than this," he said to himself again and again; "this can't be all."

He looked at his watch.

"Yes," he murmured, "that's it. I shall just have time."

Hastily donning the military overcoat of an Honorary Cornet-Major of the Bouverie Street Roughriders, he left for the Front.

Mud, and then again mud, and then very much more mud.

"Halt! Who goes there?" "Friend," said Mr. Punch hopefully. "It's Mr. Punch," said a cheerful voice. "Come in."

The Cornet-Major of the B.S.R. glissaded into the trench and found himself shaking hands with a very young subaltern of the ——th ——s. [Censored.]

"Thought I recognised you," he said. "Glad to see you out here, Sir."

"That's really what I came about," said Mr. Punch. "I want your advice."

"My advice! Good Lord!... Sure you're comfortable there? Now what'll you have? Cigar or barley-sugar?" Mr. Punch accepted a cigar.

"We're all for barley-sugar ourselves just now," the subaltern went on. "Seems kiddish, but there it is."

Mr. Punch lit his cigar and proceeded to explain himself.

"I say that I have come to consult you," he began. "It seems strange, you think. I am seventy-three, and you are——"

"Twenty-two," said the subaltern. "Next November."

"And yet Seventy-three comes here to sit at the feet of Twenty-two, and for every encouraging word that Twenty-two offers him Seventy-three will say 'Thank you!'"

"Rats," said Twenty-two for a start.

"Let me explain," said the Venerable One. "There come moments in the life of every man when he says suddenly to himself, 'What am I doing? Is it worth it?'—a moment when the work of which he has for years been proud seems all at once to be of no value whatever." The subaltern murmured something. "No, not necessarily indigestion. There may be other causes. Well, such a moment has just come to me ... and I wondered." He hesitated, and then added wistfully, "Perhaps you could say something to help me."

"The pen," said the subaltern, coughing slightly, "is mightier than the sword."

"It is," said the Sage. "I've often said so ... in Peace time."

The subaltern blushed as he searched his mind for the Historic Example.

"Didn't Wolfe say that he would rather have written what's-its-name than taken Quebec?" he asked hesitatingly.

"Yes, he did. And for most of his life the poet would have agreed with him. But, if at the moment when he read of the taking of Quebec you had asked Gray, I think he would have changed places with Wolfe very willingly.... And in Bouverie Street," added Mr. Punch, "we read of the takings of Quebecs almost every day."

The subaltern was thoughtful for a moment.

"I'll tell you a true story," he said quietly. "There was a man in this trench who had his leg shot off. They couldn't get him away till night, and here he had to wait for the whole of the day.... He stuck it out.... And what do you think he stuck it out on?"

"Morphia?" suggested Mr. Punch.

"Partly on morphia, and partly on—something else."

"Yes?" said Mr. Punch breathlessly.

"Yes—you. He read ... and he laughed ... and by-and-by the night came."

A silence came over them both. Then Mr. Punch got up quietly.

"Good-bye," he said, holding out his hand, "and thank you. That moment I spoke about seems to have gone." He took a book from under his arm and placed it in the other's hands. "I generally give this away with rather a flourish," he confessed. "This time I'll just say, 'Will you take it?' It's all there; all that I think and hope and dream, and that you out here are doing.... Good luck to you—and let me help some more of you to stick it out."

And with that he returned to Bouverie Street, leaving behind in the trench his

Partridge, Bernard.

At the Post of Honour, 203

Children's Truce (The), 519

Chronic Complaint (A), 459

Eagle Comique (The), 419

Emergency Exit (The), 11

Excursionist (The), 379

Giving the Show Away, 319

Glorious Example (A), 399

God (and the Women) our Shield, 223

Hail! Russia, 243

Killed, 499

King at the Front (The), 479

Masterpiece in the Making (A), 51

Mutual Service, 131

New Army to the Front (The), 539

Pattern of Chivalry (A), 439

Plain Duty (A), 359

Resort to the Obvious (A), 91

Road to Russia (The), 299

Triumph of "Culture" (The), 185

Unconquerable, 339

What of the Dawn?, 111

World's Enemy (The), 167

Raven-Hill, L.

At Durazzo-super-Mare, 83

Beaten on Points, 23

Carrying on, 431

Coming of the Cossacks (The), 177

Cool Stuff, 123

Dishonoured, 531

Forewarned, 371

For Friendship and Honour, 151

Fulfilment, 511

Good Hunting, 411

Greater Game (The), 331

Great Goth (The), 281

Great Illusion (The), 263

His Master's Voice, 391

India for the King, 215

Innocent (The), 471

Joseph Chamberlain, 71

Limit (The), 351

Made in Germany, 235

North Sea Chantey (A), 311

Political Jungle (The), 40-41

Power Behind (The), 103

Sinews of War (The), 491

To Arms, 195

Well Met, 161

When the Ships come Home, 3

Townsend, F. H.

Boer and Briton Too, 273

Bravo, Belgium, 143

Incorrigibles (The), 291

Liberal Cave-Men (The), 63

Men of Few Words, 451

Nothing Doing, 255

Boyle, W. P.

In Memory, 280

Brightwell, L. R.

Another Misjudged Alien, 465

Notes by a War Dog, 385

Brown, C. Hilton

Cottage (The), 138

Little Brother, 495

Caldecott, H. S.

Paris Again, 426

Campbell, A. Y.

Stick to it, Right Wing, 335

Chalmers, P. R.

At the Tower, 62

Bees (The), 121

Fact and Fable, 110

Fan, 435

Guns of Verdun, 202

Infantry, 222

In the City, 181

Jules François, 315

Kings from the East, 260

Kitty Adair, 98

Lady's Walk (The), 377

Prima Donna (The), 31

Southdowns (The), 343

Steeple (The), 279

To Limehouse, 251

Wilhelm, 348

Wireless, 395

Cobb, Miss J.

Willow Pattern Plate (The), 503

Cochrane, A.

Sporting Despatch (A), 464

Tirpitz Touch (The), 242

Collins, G. H.

To a Super-Patriot, 413

Creswell, Bulkeley

Rubbing It In, 56

Dark, Richard

Love's Labour Not Lost, 474

Voice in the Night (A), 536

Davey, Norman

R.G.A. 536

Drennan, W. St. G.

Docthor's War Speech (The), 424

Tommy Brown, Auctioneer, 466

Tommy Brown, Patriot, 394

Tommy Brown, Recruiting Sergeant, 330

Duffield, E. N.

Silvern Tongue (The), 268

Duffin, Miss

Barbara's Birthday Bear, 524

Eckersley, Arthur

Cutting Down, 268

New News (The), 179

Next (The), 541

Pacificist (The), 238

Eden, Mrs. H. P.

Prize (The), 521

Elias, F.

How Germany Came Off, 194

How War is "Made in Germany", 163

Mails for a Mailed Fist, 498

Sound and Fury, 279

Why I Don't Enlist, 410

Works of Kultur, 341

Emanuel, Walter

Catch (The), 259

Charivaria, weekly

Nut's Views on the War (A), 306

Fay, Stanley J.

Plea for Pegasus (A), 166

Price of Patriotism (The), 430

Forster, R. H.

Food War (A), 259

Garvey, Miss Ina

Blanche's Letters, 68, 206, 396

Gittins, H. N.

Double Cure (The), 129

Exercise 1, 95

Glasgow, Mrs. R.

On Earth—Peace, 521

Graham, Scott

Militant's Tariff (The), 15

Graves, C. L.

Burgomaster Max, 301

Father Wilhelm, 397

Freedom of the Press (The), 483

Imperial Infanticide (The), 537

Minor War Games, 501

New School of Divinity (The), 257

Passing of the Cow (The), 137

Super-Sympathy, 239

To Mr. Bernard Jaw, 430

Two Germanies (The), 213

War's Revenges, 464

Woman at the Fight, 25

Graves, C. L., and Lucas, E. V.

Answers to Correspondents, 171

Archibong, 382

As Others Wish to See Us, 381

Aunt Louisa's Song Scena, 414

Balm for the Brainless, 16

Choice (The), 278

Feline Amenities, 187

First Blunder (The), 230

From Another Point of View, 189

Heroes (The), 209

Limit of Ignorance (The), 424

Meditations on Mushrooms, 286

Mutability, 105

My Brother's Letter, 326

My Favourite Paper, 404

My Hardy Annual, 126

Our Literary War Lords, 378

Our Mighty Penmen, 476

Our Overburdened Heroes, 226

Oxford in Transition, 82

Politics at the Zoo, 30

Progress of Man (The), 106

Real Hero of the War (The), 532

Real Reason (The), 361

Renamed Celebrities, 313

Santa Claus at the Front, 522

Surprise (The), 346

Volumes, 145

White Man's Burden (The), 355

Haselden, Percy

En Passant, 192

Moon-Pennies, 304

Searchlights on the Mersey, 478

To a Pompadour Clock, 269

Hastings, B. Macdonald

Keeping in the Limelight, 515

Hodgkinson, T.

Benefactor (A), 462

Diplomacy, 94

Forlorn Hope (The), 486

Imports and Exports, 247

Repatriation, 426

Silent Charmer (The), 16

Stable Information, 497

To a Jaded German Pressman, 306

Viking Spirit (The), 170

Wiser Choice (The), 135

Hughes, C. E.

Restorative Power of Music (The), 150

Jenkins, Ernest

Another Innocent Victim of the War, 373

Our Colossal Arrangements, 107

Things That Do Not Matter, 321

Johnston, Alec

How Will You Take It?, 219

News from the Back of the Front, 470

Private View (The), 165

Keigwin, R. P.

Casus Belli, 366

Four Sea Lords (The), 478

To a Naval Cadet, 266

Kidd, Arthur

Awakening (The), 287

Fortune's Favourite, 198

Kill or Cure, 530

Our Daily Bread, 308

Prophets (The), 505

Strategic Disease, 416

Tours in Fact and Fancy, 58

Kingsley-Long, H.

With High Heart, 343

Knox, E. G. V.

Awakening (The), 87, 433

Cocoanuts, 127

Cut Flowers, 122

Double Life (The), 148

Error in Arcady (An), 116

Foiling of "The Blare" (The), 117

Great Petard (The), 375

Great Shock (The), 338

In Darkest Germany, 358

Jesting of Jane (The), 55

Kaiser's Hate (The), 415

Misused Talent (The), 393

New Noah's Ark (The), 234

Ode to the Spirit of Wireless Victory, 262

Peace with Honour, 458

Progress, 1

Purple Lie (The), 22

Saving of Stratford (The), 295

Scratch Handicap (The), 188

Tempering the Wind, 65

Twilight in Regent's Park, 318

Valhalla, 276

Langley, F. O.

Extenuating Circumstance (The), 146

Helpmeet (The), 304

Payment in Kind, 66

Sinecure (The), 82

Watch Dogs (The), 183, 200, 258, 284, 314, 353, 398, 453, 494, 534

Laws, A. Gordon

Censor Habit (The), 221

Lawrence C. E.

As England Expects, 260

Legard, T. F.

Victorine, 542

Lehmann, R. C.

Amanda, 75

Compulsion, 98

Crisis (The), 102

Determined Island (A), 142, 160, 176

Diary of a Kaiser, 214

For the Children, 435

Khaki Muffler (The), 364

Ode to John Bradbury, 208

Packer's Plaint (The), 130

Search for Paddington (The), 486

Teeth-Setting, 247

Unwritten Letters to the Kaiser, 254, 272, 290, 310, 345, 370, 390, 426, 450, 493, 510, 530

Walkers (The), 10

Letts, W. M.

Sea Change (A), 301

Lodge, Arthur A.

Enigma, 6

Lucas, E. V.

Entente in Being (The), 481

Marne Footnote (A), 504

Once Upon a Time, 18, 26, 76, 85

Lucy, Henry

Essence of Parliament, Weekly during Session.

"Charlie" Beresford, 401

Lulham, H.

Bob's Way, 259

Lumley, L.

Guarded Green (The), 78

My Girl Caddie, 138

Lyon, Miss L. Bowes

Britain to Belgium, 381

MacLaren, N.

Peacemaker (The), 535

Martin, N. R.

Doubt, 267

False Pretences, 355

Great Campaign (The), 241

Our Guy, 374

Recruiting Ballad (A), 443

Report Fallacious (The), 374

Terrors of War (The), 484

Too Much Championship, 69

War in Acacia Avenue (The), 303

McKay, Herbert

Top Slice (The), 108

Milne, A. A.

Armageddon, 128

At the Play, 210, 222, 246, 286

Christmas Spirit (The), 516

Double Mystery (The), 336

Enchanted Castle (The), 2

Enter Bingo, 316

Evangelist (The), 254

Fatal Gift (The), 198

First Tee (The), 89

High Jinks at Happy-Thought Hall, 496

James Feels Better, 240

Last Line (The), 275, 293, 356, 416, 476

Midsummer Madness (A), 28

Old Order Changes (The), 164

Patriot (The), 436

Peace Cigar (The), 376

Problem of Life (The), 146

Question of Light (A), 456

"They Also Serve", 182

Two Recruiting Sergeants (The), 218

Warm Half-Hour (A), 62

Mulgrew, Frank

Scandalmongrian Romance (A), 7

O'Carroll, T. Locke

Archbishop's Apologia (The), 455

Ogilvie, W. H.

War Horse of the King (A), 280

Philpotts, Eden

Cannon Fodder, 305

Plumbe, C. Conway

Debt of Honour (A), 422

Home Thoughts from the Trenches, 496

India: 1784-1914, 296

Pope, Miss Jessie

His First Victory, 217

Little and Good, 383

Outpost (The), 239

Royal Cracksman (A), 338

Richardson, R. J.

Lost Season (The), 364

Rigby, Reginald

Another War Scare, 475

Arrest (The), 363

Counting of Chickens (The), 230

Mark of Distinction (A), 78

Safeguards, 418

Suppressed Superman (The), 516

Unintelligent Anticipation, 334

Rittenberg, Max

Beats, 322

Column of Adventure (The), 208

Mystery of Prince —— (The), 383

Old Bulldog Breed (The), 424

Slump in Crime (The), 342

Wild and Woolly West End (The), 444

Seaman, Owen

Another Scrap of Paper, 290

At the Play, 96, 246, 286, 302, 344, 434, 506

Avengers (The), 194

Between Midnight and Morning, 490

Call of England (The), 176

Canute and the Kaiser, 350