BILL O’ BURNT BAY AND THE BOYS OF THE SPOT CASH COULD

NOT FATHOM THE MYSTERY OF THE BLACK EAGLE.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Billy Topsail & Company

A Story for Boys

Author: Norman Duncan

Release Date: June 15, 2009 [eBook #29130]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BILLY TOPSAIL & COMPANY***

|

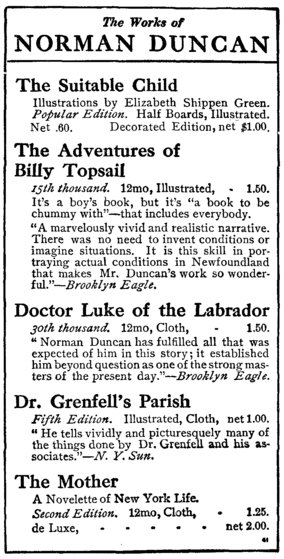

The “Billy Topsail” Books By NORMAN DUNCAN The Adventures of Billy Topsail Illustrated, cloth, $1.50 “There was no need to invent conditions or imagine situations. The life of any lad of Billy Topsail’s years up there is sufficiently romantic. It is this skill in the portrayal of actual conditions that lie ready to the hand of the intelligent observer that makes Mr. Duncan’s Newfoundland stories so noteworthy. ‘The Adventures of Billy Topsail’ is a wonderful book.”––Brooklyn Eagle. Billy Topsail and Company Illustrated, cloth, $1.50 Every boy who knows Billy Topsail will welcome this continuation of his adventuresome life in the North. Like its predecessor, the new volume is a stirring story for boys, true to life, among the hardy sons of the sea, clean, pure and stimulating. |

BILL O’ BURNT BAY AND THE BOYS OF THE SPOT CASH COULD

NOT FATHOM THE MYSTERY OF THE BLACK EAGLE.

A STORY FOR BOYS

By

NORMAN DUNCAN

Author of “The Adventures of Billy

Topsail,” “Doctor Luke of The Labrador,”

“The Mother,” “Dr. Grenfell’s Parish”

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago Toronto

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1910, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

|

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue |

To

Chauncey Lewis

and to

“Buster,”

good friends both,

sometimes to recall to them

places and occasions

at

Mike Marr’s:

Dead Man’s Point, Rolling Ledge, the

Canoe Landing, the swift and

wilful waters of the West Branch,

Squaw Mountain, the trail

to Dead Stream, the raft

on Horseshoe,

the Big Fish, the

gracious kindness of the

L. L. of E. O.,

(as well as her sandwiches),

and the never-to-be-forgotten flapjacks

that “didn’t look it”

but were indeed “all

there.”

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In Which Jimmie Grimm, Not Being Able to Help It, Is Born At Buccaneer Cove, Much to His Surprise, and Tog, the Wolf-Dog, Feels the Lash of a Seal-hide Whip and Conceives an Enmity | 15 |

| II. | In Which Jimmie Grimm is Warned Not to Fall Down, and Tog, Confirmed in Bad Ways, Raids Ghost Tickle, Commits Murder, Runs With the Wolves, Plots the Death of Jimmie Grimm and Reaches the End of His Rope | 24 |

| III. | In Which Little Jimmie Grimm Goes Lame and His Mother Discovers the Whereabouts of a Cure | 33 |

| IV. | In Which Jimmie Grimm Surprises a Secret, Jim Grimm makes a Rash Promise, and a Tourist From the States Discovers the Marks of Tog’s Teeth | 41 |

| V. | In Which Jimmie Grimm Moves to Ruddy Cove and Settles on the Slope of the Broken Nose, Where, Falling in With Billy Topsail and Donald North, He Finds the Latter a Coward, But Learns the Reason, and Scoffs no Longer. In Which, Also, Donald North Leaps a Breaker to Save a Salmon Net, and Acquires a Strut | 49 |

| VI. | In Which, Much to the Delight of Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail, Donald North, Having Perilous Business On a Pan of Ice After Night, is Cured of Fear, and Once More Puffs Out His Chest and Struts Like a Rooster | 61 |

| VII. | In Which Bagg, Imported From the Gutters of London, Lands At Ruddy Cove From the Mail-Boat, Makes the Acquaintance of Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail, and Tells Them ’E Wants to Go ’Ome. In Which, Also, the Way to Catastrophe Is Pointed | 69 |

| VIII. | In Which Bagg, Unknown to Ruddy Cove, Starts for Home, and, After Some Difficulty, Safely Gets There | 76 |

| IX. | In Which Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail, Being Added Up and Called a Man, Are Shipped For St. John’s, With Bill o’ Burnt Bay, Where They Fall In With Archie Armstrong, Sir Archibald’s Son, and Bill o’ Burnt Bay Declines to Insure the “First Venture” | 88 |

| X. | In Which the Cook Smells Smoke, and the “First Venture” In a Gale of Wind Off the Chunks, Comes Into Still Graver Peril, Which Billy Topsail Discovers | 97 |

| XI. | In Which the “First Venture” All Ablaze Forward, Is Headed For the Rocks and Breakers of the Chunks, While Bill o’ Burnt Bay and His Crew Wait for the Explosion of the Powder in Her Hold. In Which, Also, a Rope Is Put to Good Use | 102 |

| XII. | In Which Old David Grey, Once of the Hudson Bay Company, Begins the Tale of How Donald McLeod, the Factor at Fort Refuge, Scorned a Compromise With His Honour, Though His Arms Were Pinioned Behind Him and a Dozen Tomahawks Were Flourished About His Head. | 112 |

| XIII. | In Which There Are Too Many Knocks At the Gate, a Stratagem Is Successful, Red Feather Draws a Tomahawk, and an Indian Girl Appears On the Scene | 119 |

| XIV. | In Which Jimmie Grimm and Master Bagg Are Overtaken by the Black Fog in the Open Sea and Lose the Way Home While a Gale is Brewing | 130 |

| XV. | In Which it Appears to Jimmie Grimm and Master Bagg That Sixty Seconds Sometimes Make More Than a Minute | 136 |

| XVI. | In Which Archie Armstrong Joins a Piratical Expedition and Sails Crested Seas to Cut Out the Schooner “Heavenly Home” | 143 |

| XVII. | In Which Bill o’ Burnt Bay Finds Himself in Jail and Archie Armstrong Discovers That Reality is Not as Diverting as Romance | 151 |

| XVIII. | In Which Archie Inspects an Opera Bouffe Dungeon Jail, Where He Makes the Acquaintance of Dust, Dry Rot and Deschamps. In Which, Also, Skipper Bill o’ Burnt Bay Is Advised to Howl Until His Throat Cracks | 159 |

| XIX. | In Which Archie Armstrong Goes Deeper In and Thinks He Has Got Beyond His Depth. Bill o’ Burnt Bay Takes Deschamps By the Throat and the Issue Is Doubtful For a Time | 165 |

| XX. | In Which David Grey’s Friend, the Son of the Factor at Fort Red Wing, Yarns of the Professor With the Broken Leg, a Stretch of Rotten River Ice and the Tug of a White Rushing Current | 172 |

| XXI. | In Which a Bearer of Tidings Finds Himself In Peril of His Life On a Ledge of Ice Above a Roaring Rapid | 179 |

| XXII. | In Which Billy Topsail Gets an Idea and, to the Amazement of Jimmie Grimm, Archie Armstrong Promptly Goes Him One Better | 189 |

| XXIII. | In Which Sir Archibald Armstrong Is Almost Floored By a Business Proposition, But Presently Revives, and Seems to be About to Rise to the Occasion | 194 |

| XXIV. | In Which the Honour of Archie Armstrong Becomes Involved, the First of September Becomes a Date of Utmost Importance, He Collides With Tom Tulk, and a Note is Made in the Book of the Future | 203 |

| XXV. | In Which Notorious Tom Tulk o’ Twillingate and the Skipper of the “Black Eagle” Put Their Heads Together Over a Glass of Rum in the Cabin of a French Shore Trader | 212 |

| XXVI. | In Which the Enterprise of Archie Armstrong Evolves Seņor Fakerino, the Greatest Magician In Captivity. In Which, also, the Foolish are Importuned Not to be Fooled, Candy is Promised to Kids, Bill o’ Burnt Bay is Persuaded to Tussle With “The Lost Pirate,” and the “Spot Cash” Sets Sail | 220 |

| XXVII. | In Which the Amazing Operations of the “Black Eagle” Promise to Ruin the Firm of Topsail, Armstrong, Grimm & Company, and Archie Armstrong Loses His Temper and Makes a Fool of Himself | 229 |

| XXVIII. | In Which the “Spot Cash” is Caught By a Gale In the Night and Skipper Bill Gives Her Up For Lost | 239 |

| XXVIX. | In Which Opportunity is Afforded the Skipper of the “Black Eagle” to Practice Villainy in the Fog and He Quiets His Scruples. In Which, also, the Pony Islands and the Tenth of the Month Come Into Significant Conjunction | 247 |

| XXX. | In Which the Fog Thins and the Crew of the “Spot Cash” Fall Foul of a Dark Plot | 256 |

| XXXI. | In Which the “Spot Cash” is Picked up by Blow-Me-Down Rock In Jolly Harbour, Wreckers Threaten Extinction and the Honour of the Firm Passes into the Keeping of Billy Topsail | 266 |

| XXXII. | In Which the “Grand Lake” Conducts Herself In a Most Peculiar Fashion to the Chagrin of the Crew of the “Spot Cash” | 275 |

| XXXIII. | In Which Billy Topsail, Besieged by Wreckers, Sleeps on Duty and Thereafter Finds Exercise For His Wits. In Which, also, a Lighted Candle is Suspended Over a Keg of Powder and Precipitates a Critical Moment While Billy Topsail Turns Pale With Anxiety | 281 |

| XXXIV. | In Which Skipper Bill, as a Desperate Expedient, Contemplates the Use of His Teeth, and Archie Armstrong, to Save His Honour, Sets Sail in a Basket, But Seems to Have Come a Cropper | 291 |

| XXXV. | In Which Many Things Happen: Old Tom Topsail Declares Himself the Bully to Do It, Mrs. Skipper William Bounds Down the Path With a Boiled Lobster, the Mixed Accommodation Sways, Rattles, Roars, Puffs and Quits on a Grade in the Wilderness, Tom Topsail Loses His Way in the Fog and Archie Armstrong Gets Despairing Ear of a Whistle | 301 |

| XXXVI. | And Last: In Which Archie Armstrong Hangs His Head in His Father’s Office, the Pale Little Clerk Takes a Desperate Chance, Bill o’ Burnt Bay Loses His Breath, and there is a Grand Dinner in Celebration of the Final Issue, at Which the Amazement of the Crew of the “Spot Cash” is Equalled by Nothing in the World Except Their Delight | 311 |

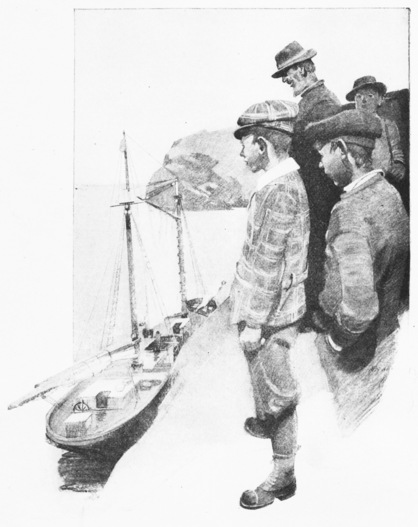

| FACING PAGE | |

| Bill O’ Burnt Bay and the Boys of the Spot Cash Could not Fathom the Mystery of the Black Eagle. | Title |

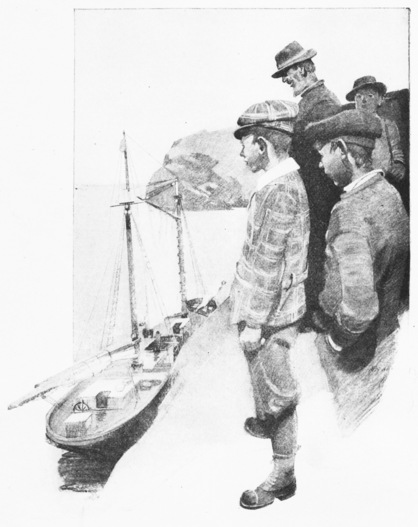

| Tog Thawed Into Limp and Servile Amiability. | 20 |

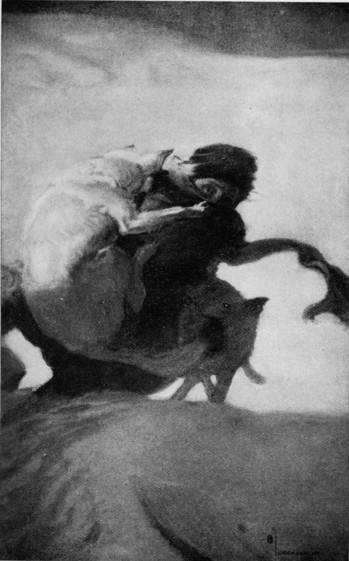

| Instinctively, He Covered His Throat With His Arms when Tog Fell Upon Him. | 28 |

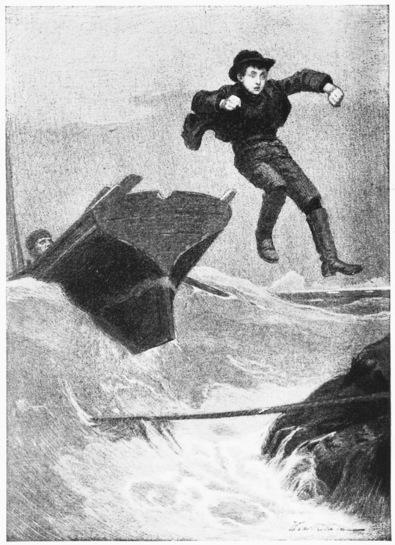

| Plucking up His Courage, Donald Leaped for the Rock. | 58 |

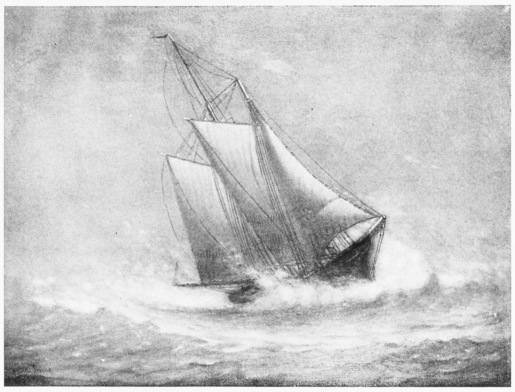

| She Was Beating Laboriously into a Violent Head Wind. | 96 |

| Buffalo Horn Looked Steadily into Mcleod’s Eyes. | 125 |

| “––We Want to Charter the On Time and Trade the Ports of the French Shore.” | 197 |

| Seņor Fakerino created Applause by Extracting Half Dollars From Vacancy. | 229 |

In Which Jimmie Grimm, Not Being Able to Help It, Is Born At Buccaneer Cove, Much to His Surprise, and Tog, the Wolf-Dog, Feels the Lash of a Seal-hide Whip and Conceives an Enmity

Young Jimmie Grimm began life at Buccaneer Cove of the Labrador. It was a poor place to begin, of course; but Jimmie had had nothing to do with that. It was by Tog, with the eager help of two hungry gray wolves, that he was taught to take care of the life into which, much to his surprise, he had been ushered. Tog was a dog with a bad name; and everybody knows that a dog with a bad name should be hanged forthwith. It should have happened to Tog. At best he was a wolfish beast. His father was a wolf; and in the end 16 Tog was as lean and savage and cunningly treacherous as any wolf of the gray forest packs. When he had done with Jimmie Grimm––and when Jimmie Grimm’s father had done with Tog––Jimmie Grimm had learned a lesson that he never could recall without a gasp and a quick little shudder.

“I jus’ don’t like t’ think o’ Tog,” he told Billy Topsail and Archie Armstrong, long afterwards.

“You weren’t afraid of him, were you?” Archie Armstrong demanded, a bit scornfully.

“Was I?” Jimmie snorted. “Huh!”

The business with Tog happened before old Jim Grimm moved south to Ruddy Cove of the Newfoundland coast, disgusted with the fishing of Buccaneer. It was before Jimmie Grimm had fallen in with Billy Topsail and Donald North, before he had ever clapped eyes on Bagg, the London gutter-snipe, or had bashfully pawed the gloved hand of Archie Armstrong, Sir Archibald’s son. It was before Donald North cured himself of fear and the First Venture had broken into a blaze in a gale of wind off the Chunks. It was before Billy Topsail, a lad of wits, had held a candle over the powder barrel, when the wreckers boarded the Spot Cash. It 17 was before Bill o’ Burnt Bay had been rescued from a Miquelon jail and the Heavenly Home was cut out of St. Pierre Harbour in the foggy night.

It was also before the Spot Cash had fallen foul of the plot to scuttle the Black Eagle. It was before the big gale and all the adventures of that northward trading voyage. In short, it was before Jim Grimm moved up from the Labrador to Ruddy Cove for better fishing.

Tog had a bad name. On the Labrador coast all dogs have bad names; nor, if the truth must be told, does the reputation do them any injustice. If evil communications corrupt good manners, the desperate character of Tog’s deeds, no less than the tragic manner of his end, may be accounted for. At any rate, long before his abrupt departure from the wilderness trails and snow-covered rock of Buccaneer Cove, he had earned the worst reputation of all the pack.

It began in the beginning. When Tog was eight weeks old his end was foreseen. He was then little more than a soft, fluffy, black-and-white ball, awkwardly perambulating on four absurdly bowed legs. Martha, Jim Grimm’s 18 wife, one day cast the lean scraps of the midday meal to the pack. What came to pass so amazed old Jim Grimm that he dropped his splitting-knife and stared agape.

“An’ would you look at that little beast!” he gasped. “That one’s a wonder for badness!”

The snarling, scrambling heap of dogs, apparently inextricably entangled, had all at once been reduced to order. Instead of a confusion of taut legs and teeth and bristling hair, there was a precise half-circle of gaunt beasts, squatted at a respectful distance from Tog’s mother, hopelessly licking their chops, while, with hair on end and fangs exposed and dripping, she kept them off.

“It ain’t Jinny,” Jim remarked. “You can’t blame she. It’s that little pup with the black eye.”

You couldn’t blame Jenny. Last of all would it occur to Martha Grimm, with a child of her own to rear, to call her in the wrong. With a litter of five hearty pups to provide for, Jenny was animated by a holy maternal instinct. But Tog, which was the one with the black eye, was not to be justified. He was imitating his mother’s tactics with diabolical success. A half-circle of whimpering puppies, keeping a respectful distance, 19 watched in grieved surprise, while, with hair on end and tiny fangs occasionally exposed, he devoured the scraps of the midday meal.

“A wonder for badness!” Jim Grimm repeated.

“‘Give a dog a bad name,’” quoted Martha, quick, like the woman she was, to resent snap-judgment of the young, “‘an’–––’”

“‘Hang un,’” Jim concluded. “Well,” he added, “I wouldn’t be s’prised if it did come t’ that.”

It did.

In Tog’s eyes there was never the light of love and humour––no amiable jollity. He would come fawning, industriously wagging his hinder parts, like puppies of more favoured degree; but all the while his black eyes were alert, hard, infinitely suspicious and avaricious. Not once, I am sure, did affection or gratitude lend them beauty. A beautiful pup he was, nevertheless––fat and white, awkwardly big, his body promising splendid strength. Even when he made war on the fleas––and he waged it unceasingly––the vigour and skill of attack, the originality of method, gave him a certain distinction. But his 20 eyes were never well disposed; the pup was neither trustful nor to be trusted.

“If he lives t’ the age o’ three,” said Jim Grimm, with a pessimistic wag of the head, “’twill be more by luck than good conduct.”

“Ah, dad,” said Jimmie Grimm, “you jus’ leave un t’ me!”

“Well, Jimmie,” drawled Jim Grimm, “it might teach you more about dogs than you know. I don’t mind if I do leave un t’ you––for a while.”

“Hut!” Jimmie boasted. “I’ll master un.”

“May be,” said Jim Grimm.

It was Jimmie Grimm who first put Tog in the traces. This was in the early days of Tog’s first winter––and of Jimmie’s seventh. The dog was a lusty youngster then; better nourished than the other dogs of Jim Grimm’s pack, no more because of greater strength and daring than a marvellous versatility in thievery. In a bored sort of way, being at the moment lazy with food stolen from Sam Butt’s stage, Tog submitted. He yawned, stretched his long legs, and gave inopportune attention to a persistent flea near the small of his back. When, however, the butt of Jimmie’s whip fell smartly on his flank, he was surprised into an appreciation of the fact that a serious attempt was being made to curtail his freedom; and he was at once alive with resentful protest.

Courtesy of “The Outing Magazine”

TOG THAWED INTO LIMP AND SERVILE AMIABILITY.

“Hi, Tog!” Jimmie complained. “Bide still!”

Tog slipped from Jimmie’s grasp and bounded off. He turned with a snarl.

“Here, Tog!” cried Jimmie.

Tog came––stepping warily over the snow. His head was low, his king-hairs bristling, his upper lip lifted.

“Ha, Tog, b’y!” said Jimmie, ingratiatingly.

Tog thawed into limp and servile amiability. The long, wiry white hair of his neck fell flat; he wagged his bushy white tail; he pawed the snow and playfully tossed his long, pointed nose as he crept near. But had Jimmie Grimm been more observant, more knowing, he would have perceived that the light in the lanky pup’s eyes had not mellowed.

“Good dog!” crooned Jimmie, stretching out an affectionate hand.

Vanished, then, in a flash, every symptom of Tog’s righteousness. His long teeth closed on Jimmie’s small hand with a snap. Jimmie struck instantly––and struck hard. The butt of the 22 whip caught Tog on the nose. He dropped the hand and leaped away with a yelp.

“Now, me b’y,” thought Jimmie Grimm, staring into the quivering dog’s eyes, not daring to glance at his own dripping hand, “I’ll master you!”

But it was no longer a question of mastery. The issue was life or death. Tog was now of an age to conceive murder. Moreover, he was of a size to justify an attempt upon Jimmie. And murder was in his heart. He crouched, quivering, his wolfish eyes fixed upon the boy’s blazing blue ones. For a moment neither antagonist ventured attack. Both waited.

It was Jimmie who lost patience. He swung his long dog whip. The lash cracked in Tog’s face. With a low growl, the dog rushed, and before the boy could evade the attack, the dog had him by the leg. Down came the butt of the whip. Tog released his hold and leaped out of reach. He pawed about, snarling, shaking his bruised head.

This advantage the boy sought to pursue. He advanced––alert, cool, ready to strike. Tog retreated. Jimmie rushed upon him. At a bound, Tog passed, turned, and came again. 23 Before Jimmie had well faced him, Tog had leaped for his throat. Down went the boy, overborne by the dog’s weight, and by the impact, which he was not prepared to withstand. But Tog was yet a puppy, unpracticed in fight; he had missed the grip. And a heavy stick, in the hands of Jimmie’s father, falling mercilessly upon him, put him in yelping retreat.

“I ’low, Jimmie,” drawled Jim Grimm, while he helped the boy to his feet, “that that dog is teachin’ you more ’n you knowed.”

“I ’low, dad,” replied the breathless Jimmie, “that he teached me nothin’ more than I forgot.”

“I wouldn’t forget again,” said Jim.

Jimmie did not deign to reply.

In Which Jimmie Grimm is Warned Not to Fall Down, and Tog, Confirmed in Bad Ways, Raids Ghost Tickle, Commits Murder, Runs With the Wolves, Plots the Death of Jimmie Grimm and Reaches the End of His Rope

Jimmie Grimm’s father broke Tog to the traces before the winter was over. A wretched time the perverse beast had of it. Labrador dogs are not pampered idlers; in winter they must work or starve––as must men, the year round. But Tog had no will for work, acknowledged no master save the cruel, writhing whip; and the whip was therefore forever flecking his ears or curling about his flanks. Moreover, he was a sad shirk. Thus he made more trouble for himself. When his team-mates discovered the failing––and this was immediately––they pitilessly worried his hind legs. Altogether, in his half-grown days, Tog led a yelping, bleeding life of it; whereby he got no more than his desserts.

Through the summer he lived by theft when 25 thievery was practicable; at other times he went fishing for himself with an ill will. Meantime, he developed strength and craft, both in extraordinary degree. There was not a more successful criminal in the pack, nor was there a more despicable bully. When the first snow fell, Tog was master at Buccaneer Cove, and had already begun to raid the neighbouring settlement at Ghost Tickle. Twice he was known to have adventured there. After the first raid, he licked his wounds in retirement for two weeks; after the second, which was made by night, they found a dead dog at Ghost Tickle.

Thereafter, Tog entered Ghost Tickle by daylight, and with his teeth made good his right to come and go at will. It was this that left him open to suspicion when the Ghost Tickle tragedy occurred. Whether or not Tog was concerned in that affair, nobody knows. They say at Ghost Tickle that he plotted the murder and led the pack; but the opinion is based merely upon the fact that he was familiar with the paths and lurking places of the Tickle––and, possibly, upon the fact of his immediate and significant disappearance from the haunts of men.

News came from Ghost Tickle that Jonathan 26 Wall had come late from the ice with a seal. Weary with the long tramp, he had left the carcass at the waterside.

“Billy,” he said to his young son, forgetting the darkness and the dogs, “go fetch that swile up.”

Billy was gone a long time.

“I wonder what’s keepin’ Billy,” his mother said.

They grew uneasy, at last; and presently they set out to search for the lad. Neither child nor seal did they ever see again; but they came upon the shocking evidences of what had occurred.

And they blamed Tog of Buccaneer Cove.

For a month or more Tog was lost to sight; but an epidemic had so reduced the number of serviceable dogs that he was often in Jim Grimm’s mind. Jim very heartily declared that Tog should have a berth with the team if starvation drove him back; not that he loved Tog, said he, but that he needed him. But Tog seemed to be doing well enough in the wilderness. He did not soon return. Once they saw him. It was when Jim and Jimmie were bound 27 home from Laughing Cove. Of a sudden Jim halted the team.

“Do you see that, Jimmie, b’y?” he asked, pointing with his whip to the white crest of a near-by hill.

“Dogs!” Jimmie ejaculated.

“Take another squint,” said Jim.

“Dogs,” Jimmie repeated.

“Wolves,” drawled Jim. “An’ do you see the beast with the black eye?”

“Why, dad,” Jimmie exclaimed, “’tis Tog!”

“I ’low,” said Jim, “that Tog don’t need us no more.”

But Tog did. He came back––lean and fawning. No more abject contrition was ever shown by dog before. He was starving. They fed him at the usual hour; and not one ounce more than the usual amount of food did he get. Next day he took his old place in the traces and helped haul Jim Grimm the round of the fox traps. But that night Jim Grimm lost another dog; and in the morning Tog had again disappeared into the wilderness. Jimmie Grimm was glad. Tog had grown beyond him. The lad could control the others of the pack; but he was helpless against Tog. 28

“I isn’t so wonderful sorry, myself,” said Jim. “I ’low, Jimmie,” he added, “that Tog don’t like you.”

“No, that he doesn’t,” Jimmie promptly agreed. “All day yesterday he snooped around, with an eye on me. Looked to me as if he was waitin’ for me to fall down.”

“Jimmie!” said Jim Grimm, gravely.

“Ay, sir?”

“You mustn’t fall down. Don’t matter whether Tog’s about or not. If the dogs is near, don’t you fall down!”

“Not if I knows it,” said Jimmie.

It was a clear night in March. The moon was high. From the rear of Jim Grimm’s isolated cottage the white waste stretched far to the wilderness. The dogs of the pack were sound asleep in the outhouse. An hour ago the mournful howling had ceased for the night. Half-way to the fish-stage, whither he was bound on his father’s errand, Jimmie Grimm came to a startled full stop.

“What was that?” he mused.

Courtesy of “The Outing Magazine”

INSTINCTIVELY, HE COVERED HIS THROAT WITH HIS ARMS WHEN TOG FELL UPON HIM.

A dark object, long and lithe, had seemed to slip like a shadow into hiding below the drying flake. Jimmie continued to muse. What had it been? A prowling dog? Then he laughed a little at his own fears––and continued on his way. But he kept watch on the flake; and so intent was he upon this, so busily was he wondering whether or not his eyes had tricked him, that he stumbled over a stray billet of wood, and fell sprawling.

He was not alarmed, and made no haste to rise; but had he then seen what emerged from the shadow of the flake he would instantly have been in screaming flight toward the kitchen door.

The onslaught of Tog and the two wolves was made silently.

There was not a howl, not a growl, not even an eager snarl. They came leaping, with Tog in the lead––and they came silently. Jimmie caught sight of them when he was half-way to his feet. He had but time to call his father’s name; and he knew that the cry would not be heard. Instinctively, he covered his throat with his arms when Tog fell upon him; and he was relieved to feel Tog’s teeth in his shoulder. He felt no pain––not any more, at any rate, than a sharp stab in the knee. He was merely sensible 30 of the fact that the vital part had not yet been reached.

In the savage joy of attack, Jimmie’s assailants forgot discretion. Snarls and growls escaped them while they worried the small body. In the manner of wolves, too, they snapped at each other. The dogs in the outhouse awoke, cocked their ears, came in a frenzy to the conflict; not to save Jimmie Grimm, but to participate in his destruction. Jimmie was prostrate beneath them all––still protecting his throat; not regarding his other parts.

And by this confusion Jim Grimm was aroused from a sleepy stupor by the kitchen fire.

“I wonder,” said he, “what’s the matter with them dogs.”

“I’m not able t’ make out,” his wife replied, puzzled, “but–––”

“Hark!” cried Jim.

They listened.

“Quick!” Jimmie’s mother screamed. “They’re at Jimmie!”

With an axe in his hand, and with merciless wrath in his heart, Jim Grimm descended upon the dogs. He stretched the uppermost dead. A second blow broke the back of a wolf. The 31 third sent a dog yelping to the outhouse with a useless hind leg. The remaining dogs decamped. Their howls expressed pain in a degree to delight Jim Grimm and to inspire him with deadly strength and purpose. Tog and the surviving wolf fled.

“Jimmie!” Jim Grimm called.

Jimmie did not answer.

“They’ve killed you!” his father sobbed. “Jimmie, b’y, is you dead? Mother,” he moaned to his wife, who had now come panting up with a broomstick, “they’ve gone an’ killed our Jimmie!”

Jimmie was unconscious when his father carried him into the house. It was late in the night, and he was lying in his own little bed, and his mother had dressed his wounds, when he revived. And Tog was then howling under his window; and there Tog remained until dawn, listening to the child’s cries of agony.

Two days later, Jim Grimm, practicing unscrupulous deception, lured Tog into captivity. That afternoon the folk of Buccaneer Cove solemnly hanged him by the neck until he was dead, which is the custom in that land. I am 32 glad that they disposed of him. He had a noble body––strong and beautiful, giving delight to the beholder, capable of splendid usefulness. But he had not one redeeming trait of character to justify his existence.

“I wonder why Tog was so bad, dad,” Jimmie mused, one day, when, as they mistakenly thought, he was near well again.

“I s’pose,” Jim explained, “’twas because his father was a wolf.”

Little Jimmie Grimm was not the same after that. For some strange reason he went lame, and the folk of Buccaneer Cove said that he was “took with the rheumatiz.”

“Wisht I could be cured,” the little fellow used to sigh.

In Which Little Jimmie Grimm Goes Lame and His Mother Discovers the Whereabouts of a Cure

Little Jimmie Grimm was then ten years old. He had been an active, merry lad, before the night of the assault of Tog and the two wolves––inclined to scamper and shout, given to pranks of a kindly sort. His affectionate, light-hearted disposition had made him the light of his mother’s eyes, and of his father’s, too, for, child though he was, lonely Jim Grimm found him a comforting companion. But he was now taken with what the folk of Buccaneer Cove called “rheumatiz o’ the knee.” There were days when he walked in comfort; but there were also times when he fell to the ground in a sudden agony and had to be carried home. There were weeks when he could not walk at all. He was not now so merry as he had been. He was more affectionate; but his eyes did not flash in the old way, nor were 34 his cheeks so fat and rosy. Jim Grimm and the lad’s mother greatly desired to have him cured.

“’Twould be like old times,” Jim Grimm said once, when Jimmie was put to bed, “if Jimmie was only well.”

“I’m afeared,” the mother sighed, “that he’ll never be well again.”

“For fear you’re right, mum,” said Jim Grimm, “we must make him happy every hour he’s with us. Hush, mother! Don’t cry, or I’ll be cryin’, too!”

Nobody connected Jimmie Grimm’s affliction with the savage teeth of Tog.

It was Jimmie’s mother who discovered the whereabouts of a cure. Hook’s Kurepain was the thing to do it! Who could deny the virtues of that “healing balm”? They were set forth in print, in type both large and small, on a creased and dirty remnant of the Montreal Weekly Globe and Family Messenger, which had providentially strayed into that far port of the Labrador. Who could dispute the works of “the invaluable discovery”? Was it not a positive cure for bruises, sprains, chilblains, cracked hands, stiffness of the joints, contraction 35 of the muscles, numbness of the limbs, neuralgia, rheumatism, pains in the chest, warts, frost bites, sore throat, quinsy, croup, and various other ills? Was it not an excellent hair restorer, as well? If it had cured millions (and apparently it had), why shouldn’t it cure little Jimmie Grimm? So Jimmie’s mother longed with her whole heart for a bottle of the “boon to suffering humanity.”

“I’ve found something, Jim Grimm,” said she, a teasing twinkle in her eye, when, that night, Jimmie’s father came in from the snowy wilderness, where he had made the round of his fox traps.

“Have you, now?” he asked, curiously. “What is it?”

“’Tis something,” said she, “t’ make you glad.”

“Come, tell me!” he cried, his eyes shining.

“I’ve heard you say,” she went on, smiling softly, “that you’d be willin’ t’ give anything t’ find it. I’ve heard you say that–––”

“’Tis a silver fox!”

“I’ve heard you say,” she continued, shaking her head, “‘Oh,’ I’ve heard you say, ‘if I could only find it I’d be happy.’”

“Tell me!” he coaxed. “Please tell me!” 36

She laid a hand on his shoulder. The remnant of the Montreal Weekly Globe and Family Messenger she held behind her.

“’Tis a cure for Jimmie,” said she.

“No!” he cried, incredulous; but there was yet the ring of hope in his voice. “Have you, now?”

“Hook’s Kurepain,” said she, “never failed yet.”

“’Tis wonderful!” said Jim Grimm.

She spread the newspaper on the table and placed her finger at that point of the list where the cure of rheumatism was promised.

“Read that,” said she, “an’ you’ll find ’tis all true.”

Jim Grimm’s eye ran up to the top of the page. His wife waited, a smile on her lips. She was anticipating a profound impression.

“‘Beauty has wonderful charms,’” Jim Grimm read. “‘Few men can withstand the witchcraft of a lovely face. All hearts are won–––’”

“No, no!” the mother interrupted, hastily. “That’s the marvellous Oriental Beautifier. I been readin’ that, too. But ’tis not that. ’Tis lower down. Beginnin’, ‘At last the universal remedy of Biblical times.’ Is you got it yet?” 37

“Ay, sure!”

And thereupon Jim Grimm of Buccaneer Cove discovered that a legion of relieved and rejuvenated rheumatics had without remuneration or constraint sung the virtues of the Kurepain and the praises of Hook. Poor ignorant Jim Grimm did not for a moment doubt the existence of the Well-Known Traveller, the Family Doctor, the Minister of the Gospel, the Champion of the World. He was ready to admit that the cure had been found.

“I’m willin’ t’ believe,” said he, solemnly, the while gazing very earnestly into his wife’s eyes, “that ’twould do Jimmie a world o’ good.”

“Read on,” said she.

“‘It costs money to make the Kurepain,’” Jim read, aloud. “‘It is not a sugar-and-water remedy. It is a cure, manufactured at great expense. Good medicines come high. But the peerless Kurepain is cheap when compared with the worthless substitutes now on the market and sold for just as good. Our price is five dollars a bottle; three bottles guaranteed to cure.’”

Jim Grimm stopped dead. He looked up. His wife steadily returned his glance. The Labrador dweller is a poor man––a very poor man. 38 Rarely does a dollar of hard cash slip into his hand. And this was hard cash. Five dollars a bottle! Five dollars for that which was neither food nor clothing!

“’Tis fearful!” he sighed.

“But read on,” said she.

“‘In order to introduce the Kurepain into this locality, we have set aside one thousand bottles of this incomparable medicine. That number, and no more, we will dispose of at four dollars a bottle. Do not make a mistake. When the supply is exhausted, the price will rise to eight dollars a bottle, owing to a scarcity of one of the ingredients. We honestly advise you, if you are in pain or suffering, to take advantage of this rare opportunity. A word to the wise is sufficient. Order to-day.’”

“’Tis a great bargain, Jim,” the mother whispered.

“Ay,” Jim answered, dubiously.

His wife patted his hand. “When Jimmie’s cured,” she went on, “he could help you with the traps, an’–––”

“’Tis not for that I wants un cured,” Jim Grimm flashed. “I’m willin’ an’ able for me labour. ’Tis not for that. I’m just thinkin’ all 39 the time about seein’ him run about like he used to. That’s what I wants.”

“Doesn’t you think, Jim, that we could manage it––if we tried wonderful hard?”

“’Tis accordin’ t’ what fur I traps, mum, afore the ice goes an’ the steamer comes. I’m hopin’ we’ll have enough left over t’ buy the cure.”

“You’re a good father, Jim,” the mother said, at last. “I knows you’ll do for the best. Leave us wait until the spring time comes.”

“Ay,” he agreed; “an’ we’ll say nar a word t’ little Jimmie.”

They laid hold on the hope in Hook’s Kurepain. Life was brighter, then. They looked forward to the cure. The old merry, scampering Jimmie, with his shouts and laughter and gambols and pranks, was to return to them. When, as the winter dragged along, Jim Grimm brought home the fox skins from the wilderness, Jimmie fondled them, and passed upon their quality, as to colour and size and fur. Jim Grimm and his wife exchanged smiles. Jimmie did not know that upon the quality and number of the skins, which he delighted to stroke and pat, depended his cure. Let the winter pass! Let the ice move out from the coast! Let the 40 steamer come for the letters! Let her go and return again! Then Jimmie should know.

“We’ll be able t’ have one bottle, whatever,” said the mother.

“’Twill be more than that, mum,” Jim Grimm answered, confidently. “We wants our Jimmie cured.”

In Which Jimmie Grimm Surprises a Secret, Jim Grimm makes a Rash Promise, and a Tourist From the States Discovers the Marks of Tog’s Teeth

With spring came the great disappointment. The snow melted from the hills; wild flowers blossomed where the white carpet had lain; the ice was ready to break and move out to sea with the next wind from the west. There were no more foxes to be caught. Jim Grimm bundled the skins, strapped them on his back, and took them to the storekeeper at Shelter Harbour, five miles up the coast; and when their value had been determined he came home disconsolate.

Jimmie’s mother had been watching from the window. “Well?” she said, when the man came in.

“’Tis not enough,” he groaned. “I’m sorry, mum; but ’tis not enough.”

She said nothing, but waited for him to continue; for she feared to give him greater distress. 42

“’Twas a fair price he gave me,” Jim Grimm continued. “I’m not complainin’ o’ that. But there’s not enough t’ do more than keep us in food, with pinchin’, till we sells the fish in the fall. I’m sick, mum––I’m fair sick an’ miserable along o’ disappointment.”

“’Tis sad t’ think,” said the mother, “that Jimmie’s not t’ be cured––after all.”

“For the want o’ twelve dollars!” he sighed.

They were interrupted by the clatter of Jimmie’s crutches, coming in haste from the inner room. Then entered Jimmie.

“I heered what you said,” he cried, his eyes blazing, his whole worn little body fairly quivering with excitement. “I heered you say ’cure.’ Is I t’ be cured?”

They did not answer.

“Father! Mama! Did you say I was t’ be cured?”

“Hush, dear!” said the mother.

“I can’t hush. I wants t’ know. Father, tell me. Is I t’ be cured?”

“Jim,” said the mother to Jim Grimm, “tell un.”

“You is!” Jim shouted, catching Jimmie in his arms, and rocking him like a baby. “You 43 is t’ be cured. Debt or no debt, lad, I’ll see you cured!”

The matter of credit was easily managed. The old storekeeper at Shelter Harbour did not hesitate. Credit? Of course, he would give Jim Grimm that. “Jim,” said he, “I’ve knowed you for a long time, an’ I knows you t’ be a good man. I’ll fit you out for the summer an’ the winter, if you wants me to, an’ you can take your own time about payin’ the bill.” And so Jim Grimm withdrew twelve dollars from the credit of his account.

They began to keep watch on the ice––to wish for a westerly gale, that the white waste might be broken and dispersed.

“Father,” said Jimmie, one night, when the man was putting him to bed, “how long will it be afore that there Kurepain comes?”

“I ’low the steamer’ll soon be here.”

“Ay?”

“An’ then she’ll take the letter with the money.”

“Ay?”

“An’ she’ll be gone about a month an’ a fortnight, an’ then she’ll be back with–––”

“The cure!” cried Jimmie, giving his father 44 an affectionate dig in the ribs. “She’ll be back with the cure!”

“Go t’ sleep, lad.”

“I can’t,” Jimmie whispered. “I can’t for joy o’ thinkin’ o’ that cure.”

By and by the ice moved out, and, in good time, the steamer came. It was at the end of a blustering day, with the night falling thick. Passengers and crew alike––from the grimy stokers to the shivering American tourists––were relieved to learn, when the anchor went down with a splash and a rumble, that the “old man” was to “hang her down” until the weather turned “civil.”

Accompanied by the old schoolmaster, who was to lend him aid in registering the letter to the Kurepain Company, Jim Grimm went aboard in the punt. It was then dark.

“You knows a Yankee when you sees one,” said he, when they reached the upper deck. “Point un out, an’ I’ll ask un.”

“Ay, I’m travelled,” said the schoolmaster, importantly. “And ’twould be wise to ask about this Kurepain Company before you post the letter.” 45

Thus it came about that Jim Grimm timidly approached two gentlemen who were chatting merrily in the lee of the wheel-house.

“Do you know the Kurepain, sir?” he asked.

“Eh? What?” the one replied.

“Hook’s, sir.”

“Hook’s? In the name of wonder, man, Hook’s what?”

“Kurepain, sir.”

“Hook’s Kurepain,” said the stranger. “Doctor,” addressing his companion, “do you recommend–––”

The doctor shrugged his shoulders.

“Then you do not?” said the other.

The doctor eyed Jim Grimm. “Why do you ask?” he inquired.

“’Tis for me little son, sir,” Jim replied. “He’ve a queer sort o’ rheumaticks. We’re thinkin’ the Kurepain will cure un. It have cured a Minister o’ the Gospel, sir, an’ a Champion o’ the World; an’ we was allowin’ that it wouldn’t have much trouble t’ cure little Jimmie Grimm. They’s as much as twelve dollars, sir, in this here letter, which I’m sendin’ away. I’m wantin’ t’ know, sir, if they’ll send the cure if I sends the money.” 46

The doctor was silent for a moment. “Where do you live?” he asked, at last.

Jim pointed to a far-off light. “Jimmie will be at that window,” he said, “lookin’ out at the steamer’s lights.”

“Do you care for a run ashore?” asked the doctor, turning to his fellow tourist.

“If it would not overtax you.”

“No, no––I’m strong enough, now. The voyage has put me on my feet again. Come––let us go.”

Jim Grimm took them ashore in the punt; guided them along the winding, rocky path; led them into the room where Jimmie sat at the window. The doctor felt of Jimmie’s knee, and asked him many questions. Then he held a whispered consultation with his companion and the schoolmaster; and of their conversation Jimmie caught such words and phrases as “slight operation” and “chloroform” and “that table” and “poor light, but light enough” and “rough and ready sort of work” and “no danger.” Then Jim Grimm was dispatched to the steamer with the doctor’s friend; and when they came back the man carried a bag in his hand. The doctor asked Jimmie a question, and 47 Jimmie nodded his head. Whereupon, the doctor called him a brave lad, and sent Jim Grimm out to the kitchen to keep his wife company for a time, first requiring him to bring a pail of water and another lamp.

When they called Jim Grimm in again––he knew what they were about, and it seemed a long, long time before the call came––little Jimmie was lying on the couch, sick and pale, with his knee tightly bandaged, but with his eyes glowing.

“Mama! Father!” the boy whispered, exultantly. “They says I’m cured.”

“Yes,” said the doctor; “he’ll be all right, now. His trouble was not rheumatism. It was caused by a fragment of the bone, broken off at the knee-joint. At least, that’s as plain as I can make it to you. He was bitten by a dog, was he not? So he says. And he remembers that he felt a stab of pain in his knee at the time. That or the fall probably accounts for it. At any rate, I have removed that fragment. He’ll be all right, after a bit. I’ve told the schoolmaster how to take care of him, and I’ll leave some medicine, and––well––he’ll soon be all right.” 48

When the doctor was about to step from the punt to the steamer’s ladder, half an hour later, Jim Grimm held up a letter to him.

“’Tis for you, sir,” he said.

“What’s this?” the doctor demanded.

“’Tis for you to keep, sir,” Jim answered, with dignity. “’Tis the money for the work you done.”

“Money!” cried the doctor. “Why, really,” he stammered, “I––you see, this is my vacation––and I–––”

“I ’low, sir,” said Jim, quietly, “that you’ll ’blige me.”

“Well, well!” exclaimed the doctor, being wise, “that I will!”

Jimmie Grimm got well long before it occurred to his father that the fishing at Buccaneer Cove was poor and that he might do better elsewhere.

In Which Jimmie Grimm Moves to Ruddy Cove and Settles on the Slope of the Broken Nose, Where, Falling in With Billy Topsail and Donald North, He Finds the Latter a Coward, But Learns the Reason, and Scoffs no Longer. In Which, Also, Donald North Leaps a Breaker to Save a Salmon Net, and Acquires a Strut

When old Jim Grimm moved to Ruddy Cove and settled his wife and son in a little white cottage on the slope of a bare hill called Broken Nose, Jimmie Grimm was not at all sorry. There were other boys at Ruddy Cove––far more boys, and jollier boys, and boys with more time to spare, than at Buccaneer. There was Billy Topsail, for one, a tow-headed, blue-eyed, active lad of Jimmie’s age; and there was Donald North, for another. Jimmie Grimm liked them both. Billy Topsail was the elder, and up to more agreeable tricks; but Donald was good enough company for anybody, and would have been quite as admirable as Billy Topsail had it not been that he was afraid of the sea. They did not call him a coward at Ruddy 50 Cove; they merely said that he was afraid of the sea.

And Donald North was.

Jimmie Grimm, himself no coward in a blow of wind, was inclined to scoff, at first; but Billy Topsail explained, and then Jimmie Grimm scoffed no longer, but hoped that Donald North would be cured of fear before he was much older. As Billy Topsail made plain to the boy, in excuse of his friend, Donald North was brave enough until he was eight years old; but after the accident of that season he was so timid that he shrank from the edge of the cliff when the breakers were beating the rocks below, and trembled when his father’s fishing punt heeled to the faintest gust.

“Billy,” he had said to Billy Topsail, on the unfortunate day when he caught the fear, being then but a little chap, “leave us go sail my new fore-an’-after. I’ve rigged her out with a fine new mizzens’l.”

“Sure, b’y!” said Billy. “Where to?”

“Uncle George’s wharf-head. ’Tis a place as good as any.”

Off Uncle George’s wharf-head the water was 51 deep––deeper than Donald could fathom at low tide––and it was cold, and covered a rocky bottom, upon which a multitude of starfish and prickly sea-eggs lay in clusters. It was green, smooth and clear, too; sight carried straight down to where the purple-shelled mussels gripped the rocks.

The tide had fallen somewhat and was still on the ebb. Donald found it a long reach from the wharf to the water. By and by, as the water ran out of the harbour, the most he could do was to touch the tip of the mast of the miniature ship with his fingers. Then a little gust of wind crept round the corner of the wharf, rippling the water as it came near. It caught the sails of the new fore-and-after, and the little craft fell over on another tack and shot away.

“Here, you!” Donald cried. “Come back, will you?”

He reached for the mast. His fingers touched it, but the boat escaped before they closed. He laughed, hitched nearer to the edge of the wharf, and reached again. The wind had failed; the little boat was tossing in the ripples, below and just beyond his grasp.

“I can’t cotch her!” he called to Billy Topsail, 52 who was back near the net-horse, looking for squids.

Billy looked up, and laughed to see Donald’s awkward position––to see him hanging over the water, red-faced and straining. Donald laughed, too. At once he lost his balance and fell forward.

This was in the days before he could swim, so he floundered about in the water, beating it wildly, to bring himself to the surface. When he came up, Billy Topsail was leaning over to catch him. Donald lifted his arm. His fingers touched Billy’s, that was all––just touched them.

Then he sank; and when he came up again, and again lifted his arm, there was half a foot of space between his hand and Billy’s. Some measure of self-possession returned. He took a long breath, and let himself sink. Down he went, weighted by his heavy boots.

Those moments were full of the terror of which, later, he could not rid himself. There seemed to be no end to the depth of the water in that place. But when his feet touched bottom, he was still deliberate in all that he did.

For a moment he let them rest on the rock. Then he gave himself a strong upward push. 53 It needed but little to bring him within reach of Billy Topsail’s hand. He shot out of the water and caught that hand. Soon afterwards he was safe on the wharf.[1]

“Sure, mum, I thought I were drownded that time!” he said to his mother, that night. “When I were goin’ down the last time I thought I’d never see you again.”

“But you wasn’t drownded, b’y,” said his mother, softly.

“But I might ha’ been,” said he.

There was the rub. He was haunted by what might have happened. Soon he became a timid, shrinking lad, utterly lacking confidence in the strength of his arms and his skill with an oar and a sail; and after that came to pass, his life was hard. He was afraid to go out to the fishing-grounds, where he must go every day with his father to keep the head of the punt up to the wind, and he had a great fear of the wind and the fog and the breakers. But he was not a coward. On the contrary, although he was circumspect in all his dealings with the sea, he never failed in his duty.

In Ruddy Cove all the men put out their salmon nets when the ice breaks up and drifts away southward, for the spring run of salmon then begins. These nets are laid in the sea, at right angles to the rocks and extending out from them; they are set alongshore, it may be a mile or two, from the narrow passage to the harbour. The outer end is buoyed and anchored, and the other is lashed to an iron stake which is driven deep into some crevice of the rock.

When belated icebergs hang offshore a watch must be kept on the nets, lest they be torn away or ground to pulp by the ice.

“The wind’s haulin’ round a bit, b’y,” said Donald’s father, one day in spring, when the lad was twelve years old, and he was in the company of Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail on the sunny slope of the Broken Nose. “I think ’twill freshen and blow inshore afore night.”

“They’s a scattered pan of ice out there, father,” said Donald, “and three small bergs.”

“Yes, b’y, I knows,” said North. “’Tis that I’m afeared of. If the wind changes a bit more, ’twill jam the ice agin the rocks. Does you think the net is safe?” 55

Jimmie Grimm glanced at Billy Topsail; and Billy Topsail glanced at Jimmie Grimm.

“Wh-wh-what, sir?” Donald stammered.

It was quite evident that the net was in danger, but since Donald had first shown sign of fearing the sea, Job North had not compelled him to go out upon perilous undertakings. He had fallen into the habit of leaving the boy to choose his own course, believing that in time he would master himself.

“I says,” he repeated, quietly, “does you think that net’s in danger?”

Billy Topsail nudged Jimmie Grimm. They walked off together. It would never do to witness a display of Donald’s cowardice.

“He’ll not go,” Jimmie Grimm declared.

“’Tis not so sure,” said Billy.

“I tell you,” Jimmie repeated, confidently, “that he’ll never go out t’ save that net.” “But!” he added; “he’ll have no heart for the leap.”

“I think he’ll go,” Billy insisted.

In the meantime Job North had stood regarding his son.

“Well, son,” he sighed, “what you think about that net?” 56

“I think, sir,” said Donald, steadily, between his teeth, “that the net should come in.”

Job North patted the boy on the back. “’Twould be wise, b’y,” said he, smiling. “Come, b’y; we’ll go fetch it.”

“So long, Don!” Billy Topsail shouted delightedly.

Donald and his father put out in the punt. There was a fair, fresh wind, and with this filling the little brown sail, they were soon driven out from the quiet water of the harbour to the heaving sea itself. Great swells rolled in from the open and broke furiously against the coast rocks. The punt ran alongshore for two miles, keeping well away from the breakers. When at last she came to that point where Job North’s net was set, Donald furled the sail and his father took up the oars.

“’Twill be a bit hard to land,” he said.

Therein lay the danger. There is no beach along that coast. The rocks rise abruptly from the sea––here, sheer and towering; there, low and broken. When there is a sea running, the swells roll in and break against these rocks; and when the breakers catch a punt, they are certain to smash it to splinters. 57

The iron stake to which Job North’s net was lashed was fixed in a low ledge, upon which some hardy shrubs had taken root. The waves were casting themselves against the rocks below, breaking with a great roar and flinging spray over the ledge.

“’Twill be a bit hard,” North said again.

But the salmon-fishers have a way of landing under such conditions. When their nets are in danger they do not hesitate. The man at the oars lets the boat drift with the breaker stern foremost towards the rocks. His mate leaps from the stern seat to the ledge. Then the other pulls the boat out of danger before the wave curls and breaks. It is the only way.

But sometimes the man in the stern miscalculates––leaps too soon, stumbles, leaps short. He falls back, and is almost inevitably drowned. Sometimes, too, the current of the wave is too strong for the man at the oars; his punt is swept in, pull as hard as he may, and he is overwhelmed with her. Donald knew all this. He had lived in dread of the time when he must first make that leap.

“The ice is comin’ in, b’y,” said North. “’Twill scrape these here rocks, certain sure. 58 Does you think you’re strong enough to take the oars an’ let me go ashore?”

“No, sir,” said Donald.

“You never leaped afore, did you?”

“No, sir.”

“Will you try it now, b’y?” said North, quietly.

“Yes, sir,” Donald said, faintly.

“Get ready, then,” said North.

With a stroke or two of the oars Job swung the stern of the boat to the rocks. He kept her hanging in this position until the water fell back and gathered in a new wave; then he lifted his oars. Donald was crouched on the stern seat, waiting for the moment to rise and spring.

The boat moved in, running on the crest of the wave which would a moment later break against the rock. Donald stood up, and fixed his eye on the ledge. He was afraid; all the strength and courage he possessed seemed to desert him. The punt was now almost on a level with the ledge. The wave was about to curl and fall. It was the precise moment when he must leap––that instant, too, when the punt must be pulled out of the grip of the breaker, if at all.

Billy Topsail and Jimmie Grimm were at this critical moment hanging off Grief Island, in the lee, whence they could see all that occurred. They had come out to watch the issue of Donald’s courage.

Courtesy of “The Youth’s Companion”

PLUCKING UP HIS COURAGE, DONALD LEAPED FOR THE ROCK.

“He’ll never leap,” Jimmie exclaimed.

“He will,” said Billy.

“He’ll not,” Jimmie declared.

“Look!” cried Billy.

Donald felt of a sudden that he must do this thing. Therefore why not do it courageously? He leaped; but this new courage had not come in time. He made the ledge, but he fell an inch short of a firm footing. So for a moment he tottered, between falling forward and falling back. Then he caught the branch of an overhanging shrub, and with this saved himself. When he turned, Job had the punt in safety; but he was breathing hard, as if the strain had been great.

“’Twas not so hard, was it, b’y?” said Job.

“No, sir,” said Donald.

“I told you so,” said Billy Topsail to Jimmie Grimm.

“Good b’y!” Jimmie declared, as he hoisted the sail for the homeward run.

Donald cast the net line loose from its mooring, and saw that it was all clear. His father let 60 the punt sweep in again. It is much easier to leap from a solid rock than from a boat, so Donald jumped in without difficulty. Then they rowed out to the buoy and hauled the great, dripping net over the side.

It was well they had gone out, for before morning the ice had drifted over the place where the net had been. More than that, Donald North profited by his experience. He perceived that if perils must be encountered, they are best met with a clear head and an unflinching heart.

“Wisht you’d been out t’ see me jump the day,” he said to Jimmie Grimm, that night.

Billy and Jimmie laughed.

“Wisht you had,” Donald repeated.

“We was,” said Jimmie.

Donald threw back his head, puffed out his chest, dug his hands in his pockets and strutted off. It was the first time, poor lad! he had ever won the right to swagger in the presence of Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail. To be sure, he made the most of it!

But he was not yet cured.

Donald North himself told me this––told me, too, what he had thought, and what he said to his mother––N. D.

In Which, Much to the Delight of Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail, Donald North, Having Perilous Business On a Pan of Ice After Night, is Cured of Fear, and Once More Puffs Out His Chest and Struts Like a Rooster

Like many another snug little harbour on the northeast coast of Newfoundland, Ruddy Cove is confronted by the sea and flanked by a vast wilderness; so all the folk take their living from the sea, as their forebears have done for generations. In the gales and high seas of the summer following, and in the blinding snow-storms and bitter cold of the winter, Donald North grew in fine readiness to face peril at the call of duty. All that he had gained was put to the test in the next spring, when the floating ice, which drifts out of the north in the spring break-up, was driven by the wind against the coast.

After that adventure, Jimmie Grimm said:

“You’re all right, Don!”

And Billy Topsail said:

Donald North, himself, stuck his hands in his pockets, threw out his chest, spat like a skipper and strutted like a rooster.

“I ’low I is!” said he.

And he was. And nobody decried his little way of boasting, which lasted only for a day; and everybody was glad that at last he was like other boys.

Job North, with Alexander Bludd and Bill Stevens, went out on the ice to hunt seal. The hunt led them ten miles offshore. In the afternoon of that day the wind gave some sign of changing to the west, and at dusk it was blowing half a gale offshore. When the wind blows offshore it sweeps all this wandering ice out to sea, and disperses the whole pack.

“Go see if your father’s comin’, b’y,” said Donald’s mother. “I’m gettin’ terrible nervous about the ice.”

Donald took his gaff––a long pole of the light, tough dogwood, two inches thick and shod with iron––and set out. It was growing dark. The wind, rising still, was blowing in strong, cold gusts. It began to snow while he was yet on the ice of the harbour, half a mile away 63 from the pans and dumpers which the wind of the day before had crowded against the coast.

When he came to the “standing edge”––the stationary rim of ice which is frozen to the coast––the wind was thickly charged with snow. What with dusk and snow, he found it hard to keep to the right way. But he was not afraid for himself; his only fear was that the wind would sweep the ice-pack out to sea before his father reached the standing edge. In that event, as he knew, Job North would be doomed.

Donald went out on the standing edge. Beyond lay a widening gap of water. The pack had already begun to move out.

There was no sign of Job North’s party. The lad ran up and down, hallooing as he ran; but for a time there was no answer to his call. Then it seemed to him that he heard a despairing hail, sounding far to the right, whence he had come. Night had almost fallen, and the snow added to its depth; but as he ran back Donald could still see across the gap of water to the great pan of ice, which, of all the pack, was nearest to the standing edge. He perceived that the gap had considerably widened since he had first observed it.

“Is that you, father?” he called. 64

“Ay, Donald,” came an answering hail from directly opposite. “Is there a small pan of ice on your side?”

Donald searched up and down the standing edge for a detached cake large enough for his purpose. Near at hand he came upon a small, thin pan, not more than six feet square.

“Haste, b’y!” cried his father.

“They’s one here,” he called back, “but ’tis too small. Is there none there?”

“No, b’y. Fetch that over.”

Here was desperate need. If the lad were to meet it, he must act instantly and fearlessly. He stepped out on the pan and pushed off with his gaff. Using his gaff as a paddle––as these gaffs are constantly used in ferrying by the Newfoundland fishermen––and helped by the wind, he soon ferried himself to where Job North stood waiting with his companions.

“’Tis too small,” said Stevens. “’Twill not hold two.”

North looked dubiously at the pan. Alexander Bludd shook his head in despair.

“Get back while you can, b’y,” said North. “Quick! We’re driftin’ fast! The pan’s too small.” 65

“I thinks ’tis big enough for one man an’ me,” said Donald.

“Get aboard an’ try it, Alexander,” said Job. “Quick, man!”

Alexander Bludd stepped on. The pan tipped fearfully, and the water ran over it; but when the weight of the man and the boy was properly adjusted, it seemed capable of bearing them both across. They pushed off, and seemed to go well enough; but when Alexander moved to put his gaff in the water the pan tipped again. Donald came near losing his footing. He moved nearer the edge and the pan came to a level. They paddled with all their strength, for the wind was blowing against them, and there was need of haste if three passages were to be made. Meantime the gap had grown so wide that the wind had turned the ripples into waves, which washed over the pan as high as Donald’s ankles.

But they came safely across. Bludd stepped swiftly ashore, and Donald pushed off. With the wind in his favour he was soon once more at the other side.

“Now, Bill,” said North; “your turn next.”

“I can’t do it, Job,” said Stevens. “Get aboard yourself. The lad can’t come back again. 66

“We’re driftin’ out too fast. He’s your lad, an’ you’ve the right to–––”

“Ay, I can come back,” said Donald. “Come on, Bill! Be quick!”

Stevens was a lighter man than Alexander Bludd; but the passage was wider, and still widening, for the pack had gathered speed. When Stevens was safely landed he looked back. A vast white shadow was all that he could see. Job North’s figure had been merged with the night.

“Donald, b’y,” he said, “you got t’ go back for your father, but I’m fair feared you’ll never–––”

“Give me a push, Bill,” said Donald.

Stevens caught the end of the gaff and pushed the lad out.

“Good-bye, Donald,” he called.

When the pan touched the other side Job North stepped aboard without a word. He was a heavy man. With his great body on the ice-cake, the difficulty of return was enormously increased, as Donald had foreseen. The pan was overweighted. Time and again it nearly shook itself free of its load and rose to the surface. North was near the centre, plying his gaff with 67 difficulty, but Donald was on the extreme edge. Moreover, the distance was twice as great as it had been at first, and the waves were running high, and it was dark.

They made way slowly. The pan often wavered beneath them; but Donald was intent upon the thing he was doing, and he was not afraid. Then came the time––they were but ten yards off the standing edge––when North struck his gaff too deep into the water. He lost his balance, struggled to regain it, failed––and fell off. Before Donald was awake to the danger, the edge of the pan sank under him, and he, too, toppled off.

Donald had learned to swim now. When he came to the surface, his father was breast-high in the water, looking for him.

“Are you all right, Donald?” said his father.

“Yes, sir.”

“Can you reach the ice alone?”

“Yes, sir,” said Donald, quietly.

Alexander Bludd and Bill Stevens helped them up on the standing edge, and they were home by the kitchen fire in half an hour.

“’Twas bravely done, b’y,” said Job.

So Donald North learned that perils feared 68 are much more terrible than perils faced. He had a courage of the finest kind, in the following days of adventure, now close upon him, had young Donald.

In Which Bagg, Imported From the Gutters of London, Lands At Ruddy Cove From the Mail-Boat, Makes the Acquaintance of Jimmie Grimm and Billy Topsail, and Tells Them ’E Wants to Go ’Ome. In Which, Also, the Way to Catastrophe Is Pointed

The mail-boat comes to Ruddy Cove in the night, when the shadows are black and wet, and the wind, blowing in from the sea, is charged with a clammy mist. The lights in the cottages are blurred by the fog. They form a broken line of yellow splotches rounding the harbour’s edge. Beyond is deep night and a wilderness into which the wind drives. In the morning the fog still clings to the coast. Within the cloudy wall it is all glum and dripping wet. When a veering wind sweeps the fog away, there lies disclosed a world of rock and forest and fuming sea, stretching from the end of the earth to the summits of the inland hills––a place of ruggedness and hazy distances; of silence and a vast, forbidding loneliness. 70

It was on such a morning that Bagg, the London gutter-snipe, having been landed at Ruddy Cove from the mail-boat the night before––this being in the fall before Donald North played ferryman between the standing edge and the floe––it was on such a foggy morning, I say, that Bagg made the acquaintance of Billy Topsail and Jimmie Grimm.

“Hello!” said Billy Topsail.

“Hello!” Jimmie Grimm echoed.

“You blokes live ’ere?” Bagg whined.

“Uh-huh,” said Billy Topsail.

“This yer ’ome?” pursued Bagg.

Billy nodded.

“Wisht I was ’ome!” sighed Bagg. “I say,” he added, “which way’s ’ome from ’ere?”

“You mean Skipper ’Zekiel’s cottage?”

“I mean Lun’on,” said Bagg.

“Don’t know,” Billy answered. “You better ask Uncle Tommy Luff. He’ll tell you.”

Bagg had been exported for adoption. The gutters of London are never exhausted of their product of malformed little bodies and souls; they provide waifs for the remotest colonies of the empire. So, as it chanced, Bagg had been exported to Newfoundland––transported from his 71 native alleys to this vast and lonely place. Bagg was scrawny and sallow, with bandy legs and watery eyes and a fantastic cranium; and he had a snub nose, which turned blue when a cold wind struck it. But when he was landed from the mail-boat he found a warm welcome, just the same, from Ruth Rideout, Ezekiel’s wife, by whom he had been taken for adoption.

Later in the day, old Uncle Tommy Luff, just in from the fishing grounds off the Mull, where he had been jigging for stray cod all day long, had moored his punt to the stage-head, and he was now coming up the path with his sail over his shoulder, his back to the wide, flaring sunset. Bagg sat at the turn to Squid Cove, disconsolate. The sky was heavy with glowing clouds, and the whole earth was filled with a glory such as he had not known before.

“Shall I arst the ol’ beggar when ’e gets ’ere?” mused Bagg.

Uncle Tommy looked up with a smile.

“I say, mister,” piped Bagg, when the old man came abreast, “which way’s ’ome from ’ere?”

“Eh, b’y?” said Uncle Tommy. 72

“’Ome, sir. Which way is ’ome from ’ere?”

In that one word Bagg’s sickness of heart expressed itself––in the quivering, wistful accent.

“Is you ’Zekiel Rideout’s lad?” said Uncle Tommy.

“Don’t yer make no mistake, mister,” said Bagg, somewhat resentfully. “I ain’t nothink t’ nobody.”

“I knowed you was that lad,” Uncle Tommy drawled, “when I seed the size o’ you. Sure, b’y, you knows so well as me where ’Zekiel’s place is to. ’Tis t’ the head o’ Burnt Cove, there, with the white railin’, an’ the tater patch aft o’ the place where they spreads the fish. Sure, you knows the way home.”

“I mean Lun’on, mister,” Bagg urged.

“Oh, home!” said Uncle Tommy. “When I was a lad like you, b’y, just here from the West Country, me fawther told me if I steered a course out o’ the tickle an’ kept me starn fair for the meetin’-house, I’d sure get home t’ last.”

“Which way, mister?”

Uncle Tommy pointed out to sea––to that far place in the east where the dusk was creeping up over the horizon.

“There, b’y,” said he. “Home lies there.” 73

Then Uncle Tommy shifted his sail to the other shoulder and trudged on up the hill; and Bagg threw himself on the ground and wept until his sobs convulsed his scrawny little body.

“I want to go ’ome!” he sobbed. “I want to go ’ome!”

No wonder that Bagg, London born and bred, wanted to go home to the crowd and roar and glitter of the streets to which he had been used. It was fall in Ruddy Cove, when the winds are variable and gusty, when the sea is breaking under the sweep of a freshening breeze and yet heaving to the force of spent gales. Fogs, persistently returning with the east wind, filled the days with gloom and dampness. Great breakers beat against the harbour rocks; the swish and thud of them never ceased, nor was there any escape from it.

Bagg went to the fishing grounds with Ezekiel Rideout, where he jigged for the fall run of cod; and there he was tossed about in the lop, and chilled to the marrow by the nor’easters. Many a time the punt ran heeling and plunging for the shelter of the harbour, with the spray falling upon Bagg where he cowered amidships; and 74 once she was nearly undone by an offshore gale. In the end Bagg learned consideration for the whims of a punt and acquired an unfathomable respect for a gust and a breaking wave.

Thus the fall passed, when the catching and splitting and drying of fish was a distraction. Then came the winter––short, drear days, mere breaks in the night, when there was no relief from the silence and vasty space round about, and the dark was filled with the terrors of snow and great winds and loneliness. At last the spring arrived, when the ice drifted out of the north in vast floes, bearing herds of hair-seal within reach of the gaffs of the harbour folk, and was carried hither and thither with the wind.

Then there came a day when the wind gathered the dumpers and pans in one broad mass and jammed it against the coast. The sea, where it had lain black and fretful all winter long, was now covered and hidden. The ice stretched unbroken from the rocks of Ruddy Cove to the limit of vision in the east. And Bagg marvelled. There seemed to be a solid path from Ruddy Cove straight away in the direction in which Uncle Tommy Luff had said that England lay.

Notwithstanding the comfort and plenty of 75 his place with Aunt Ruth Rideout and Uncle Ezekiel, Bagg still longed to go back to the gutters of London.

“I want to go ’ome,” he often said to Billy Topsail and Jimmie Grimm.

“What for?” Billy once demanded.

“Don’t know,” Bagg replied. “I jus’ want to go ’ome.”

At last Bagg formed a plan.

In Which Bagg, Unknown to Ruddy Cove, Starts for Home, and, After Some Difficulty, Safely Gets There

Uncle Tommy Luff, coming up the hill one day when the ice was jammed against the coast and covered the sea as far as sight carried, was stopped by Bagg at the turn to Squid Cove.

“I say, mister,” said Bagg, “which way was you tellin’ me Lun’on was from ’ere?”

Uncle Tommy pointed straight out to the ice-covered sea.

“That way?” asked Bagg.

“Straight out o’ the tickle with the meetin’-house astarn.”

“Think a bloke could ever get there?” Bagg inquired.

Uncle Tommy laughed. “If he kep’ on walkin’ he’d strike it some time,” he answered.

“Sure?” Bagg demanded.

“If he kep’ on walkin’,” Uncle Tommy repeated, smiling. 77

This much may be said of the ice: the wind which carries it inshore inevitably sweeps it out to sea again, in an hour or a day or a week, as it may chance. The whole pack––the wide expanse of enormous fragments of fields and glaciers––is in the grip of the wind, which, as all men know, bloweth where it listeth. A nor’east gale sets it grinding against the coast, but when the wind veers to the west the pack moves out and scatters.

If a man is caught in that great rush and heaving, he has nothing further to do with his own fate but wait. He escapes if he has strength to survive until the wind blows the ice against the coast again––not else. When the Newfoundlander starts out to the seal hunt he makes sure, in so far as he can, that no change in the wind is threatened.

Uncle Ezekiel Rideout kept an eye on the weather that night.

“Be you goin’, b’y?” said Ruth, looking up from her weaving.

Ezekiel had just come in from Lookout Head, where the watchers had caught sight of the seals, swarming far off in the shadows.

“They’s seals out there,” he said, “but I 78 don’t know as us’ll go the night. ’Tis like the wind’ll haul t’ the west.”

“What do Uncle Tommy Luff say?”

“That ’twill haul t’ the west an’ freshen afore midnight.”

“Sure, then, you’ll not be goin’, b’y?”

“I don’t know as anybody’ll go,” said he. “Looks a bit too nasty for ’em.”

Nevertheless, Ezekiel put some pork and hard-bread in his dunny bag, and made ready his gaff and tow-lines, lest, by chance, the weather should promise fair at midnight.

“Where’s that young scamp?” said Ezekiel, with a smile––a smile which expressed a fine, indulgent affection.

“Now, I wonder where he is?” said Ruth, pausing in her work. “He’ve been gone more’n an hour, sure.”

“Leave un bide where he is so long as he likes,” said he. “Sure he must be havin’ a bit o’ sport. ’Twill do un good.”

Ezekiel sat down by the fire and dozed. From time to time he went to the door to watch the weather. From time to time Aunt Ruth listened for the footfalls of Bagg coming up the path. After a long time she put her work away. 79 The moon was shining through a mist; so she sat at the window, for from there she could see the boy when he rounded the turn to the path. She wished he would come home.

“I’ll go down t’ Topsail’s t’ see what’s t’ be done about the seals,” said Ezekiel.

“Keep a lookout for the b’y,” said she.

Ezekiel was back in half an hour. “Topsail’s gone t’ bed,” said he. “Sure, no one’s goin’ out the night. The wind’s hauled round t’ the west, an’ ’twill blow a gale afore mornin’. The ice is movin’ out slow a’ready. Be that lad out yet?”

“Yes, b’y,” said Ruth, anxiously. “I wisht he’d come home.”

“I––I––wisht he would,” said Ezekiel.

Ruth went to the door and called Bagg by name.

But there was no answer.

Offshore, four miles offshore, Bagg was footing it for England as fast as his skinny little legs would carry him. The way was hard––a winding, uneven path over the pack. It led round clumpers, over ridges which were hard to scale, and across broad, slippery pans. The frost had 80 glued every fragment to its neighbour; for the moment the pack formed one solid mass, continuous and at rest, but the connection between its parts was of the slenderest, needing only a change of the wind or the ground swell of the sea to break it everywhere.

The moon was up. It was half obscured by a haze which was driving out from the shore, to which quarter the wind had now fairly veered. The wind was rising––coming in gusts, in which, soon, flakes of snow appeared. But there was light enough to keep to the general direction out from the coast, and the wind but helped Bagg along.

“I got t’ ’urry up,” thought he.

The boy looked behind. Ruddy Cove was within sight. He was surprised that the coast was still so near.

“Got t’ ’urry up a bit more,” he determined.

He was elated––highly elated. He thought that his old home was but a night’s journey distant; at most, not more than a night and a day, and he had more than food enough in his pockets to last through that. He was elated; but from time to time a certain regret entered in, and it was not easily cast out. He remembered 81 the touch of Aunt Ruth’s lips, and her arm, which had often stolen about him in the dusk; and he remembered that Uncle Ezekiel had beamed upon him most affectionately, in times of mischief and good works alike. He had been well loved in Ruddy Cove.

“Wisht I’d told Aunt Ruth,” Bagg thought.

On he trudged––straight out to sea.

“Got t’ ’urry up,” thought he.

Again the affection of Aunt Ruth occurred to him. She had been very kind; and as for Uncle ’Zeke––why, nobody could have been kinder.

“Wisht I ’ad told Aunt Ruth,” Bagg regretted. “Might o’ said good-bye anyhow.”

The ice was now drifting out; but the wind had not yet risen to that measure of strength wherewith it tears the pack to pieces, nor had the sea attacked it. There was a gap of two hundred yards between the coast rocks and the edge of the ice, but that was far, far back, and hidden from sight. The pack was drifting slowly, smoothly, still in one compact mass. Its motion was not felt by Bagg, who pressed steadily on toward England, eager again, but fast growing weary.

“Got t’ ’urry up,” thought he. 82

But presently he must rest; and while he rested the wind gathered strength. It went singing over the pack, pressing ever with a stronger hand upon its dumpers and ridges––pushing it, everywhere, faster and faster out to sea. The pack was on the point of breaking in pieces under the strain, but the wind still fell short of the power to rend it. There was a greater volume of snow falling; it was driven past in thin, swirling clouds. Hence the light of the moon began to fail. Far away, at the rim of the pack, the sea was eating its way in, but the swish and crash of its work was too far distant to be heard.

“I ain’t nothink t’ nobody but Aunt Ruth,” Bagg thought, as he rose to continue the tramp.

On he went, the wind lending him wings; but at last his legs gave out at the knees, and he sat down again to rest. This was in the lee of a clumper, where he was comfortably sheltered. He was still warm––in a glow of heat, indeed––and his hope was still with him. So far he had suffered from nothing save weariness. So he began to dream of what he would do when he got home, just as all men do when they come near, once again, to that old place where they were born. The wind was now 83 a gale, blowing furiously; the pack was groaning in its outlying parts.

“Nothink t’ nobody,” Bagg grumbled, on his way once more.