The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Military Genius, by Sarah Ellen Blackwell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Military Genius

Life of Anna Ella Carroll of Maryland

Author: Sarah Ellen Blackwell

Release Date: June 23, 2007 [EBook #21909]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A MILITARY GENIUS ***

Produced by David Edwards, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all

other inconsistencies are as in the original. Author's spelling has

been maintained.

Closing quote added after "Japan has to wall themselves in".]

Anna Ella Carroll

("The great unrecognized member of Lincoln's Cabinet.")

COMPILED FROM FAMILY RECORDS AND CONGRESSIONAL DOCUMENTS

BY

SARAH ELLEN BLACKWELL.

For Sale at the Office of the Woman's Journal, 3 Park Street, Boston, Mass. Rooms of the Woman's Suffrage Society, 1406 G St., Washington, D. C.

Price: $1.10 (Forwarded free on receipt of price).

WASHINGTON, D. C.

JUDD & DETWEILER, PRINTERS.

1891.

Entered in the office of the Librarian of Congress, 1891.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The long years come and go,

And the Past,

The sorrowful splendid Past,

With its glory and its woe,

Seems never to have been.

Seems never to have been!

O somber days and grand,

How ye crowd back once more,

Seeing our heroes graves are green

By the Potomac, and the Cumberland

And in the valley of the Shenandoah!

When we remember how they died,

In dark ravine and on the mountain side,

In leaguered fort and fire-encircled town,

And where the iron ships went down.

How their dear lives were spent

In the weary hospital tent,

In the cockpit's crowded hive,

—— it seems

Ignoble to be alive!

Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

Chapter I.

Ancestry and Old Plantation Life

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

(p. vi)Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Miss Carroll's Pamphlets in Aid of the Administration — The Presentation of the Bill

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

In commencing the attempt to portray a very remarkable career I had hoped for the coöperation of the person concerned so far, at least, as the supervision of any statements I might find it necessary to make. But it was decided by her friends that it would not be well for her at present to be troubled with new projects, or even informed of them. It was at first a serious disappointment to me and seemed to increase my difficulties, but as I was allowed access to sources of family information I have been enabled to present a sketch, slight and inadequate, but authentic, and greatly desired by many distant friends. With continued improvement in health I trust that the wishes of Miss Carroll's friends may be better met by an autobiography taking the place of the present meager and imperfect sketch.

It should be at once understood that this is not a plea for Miss Carroll.

Her work has but to be fairly presented to speak for itself.

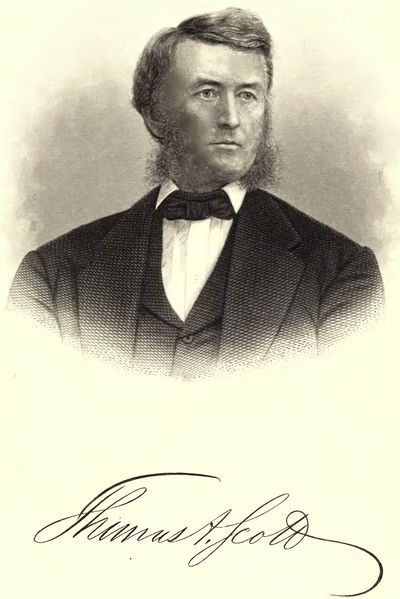

Her claim was settled once and forever by the evidence given before the first Military Committee of 1871, met to consider the claim, and reporting, through Senator Howard, unanimously endorsing every fact. The Assistant Secretary (p. viii) of War, Thomas A. Scott, the Chairman of the Committee for the Conduct of the War, Benjamin F. Wade, and Judge Evans, of Texas, testifying in a manner that was conclusive. These men knew what they were talking about and human testimony could no farther go. Congress, through its committees, has again and again endorsed the claim, and never denied it, being "adverse" only to award as involving national recognition.

Our great generals have left us one by one without ever antagonizing the claim, and General Grant advised Miss Carroll to continue to push her claim for recognition.

But this work is to be considered rather in the light of an historical research bearing on questions of the day.

Are our present laws and customs just toward women? Are women ever preėminently fitted for high offices in the State? Is it for our honor and advantage when so fitted to avail ourselves of the whole united intellect and moral power of men and women side by side in peril and in duty? Such a life as this gives to all these questions the authoritative answer of established facts.

New York, April 21st, 1891. (Summer address, Lawrence, Long Island, N. Y.)

Miss Carroll's address is 931 New Hampshire Avenue, Washington, D. C.

Arriving as a stranger in Washington, knowing nothing of libraries and document rooms, Secretaries offices, and War departments, I was at first greatly at a loss. For many years I had had in my possession two very important documents, the last memorial of 1878 and the report of the Military Committee thereon under General Bragg in 1881. With these two in my hand I proceeded to consult the Descriptive Catalogue of the Congressional Library. To my surprise, I found that these two very important documents had been omitted from the index. Calling attention to the fact, we looked them up in the body of the volume and Mr. Spofford immediately added them in pencil together with the other important documents, in Miss Carroll's favor, which had also been omitted. When I made my way to the Senate document room I found that this important Miss. Doc. 58 had been omitted there also, having been set down under another name. Looking it up in the volume of Miscellaneous Documents I again obtained the admission by Mr. Amzi Smith. In the list at the Secretaries office Miss. Doc. 58 was also omitted together with the last report by a Military Committee, under General Bragg, endorsing the claim in the most thorough going way. The index ending with an intermediate report mistakenly (p. x) designated as adverse, though the previous reports were not thus heralded as favorable.

After the first report, as made by Senator Howard and the repeated endorsements made by Wilson and Williams of succeeding Congresses, these two documents are by far the most important and interesting.

The memorial of '78, containing additional evidence explaining some things, otherwise unaccountable, and making some very singular revelations. It is a mine of wealth for the future historian. At the Secretary's office I showed the documents and stated that their exclusion must have been unfavorable to the presentation of the case. I was not equally fortunate in obtaining their immediate admission, but trust the mistake has since been rectified.

The report marked as "adverse" would be more truly described as "admission of the incontestable nature of the evidence in support of the claim," admitting the services in every particular and being "adverse" only to award involving national recognition.

At the Secretary's office I obtained permission to see the file of the 41st Congress, 2d. session. There I saw the first short memorial with the plan of campaign attached as described by Thomas Scott. Then my investigations were temporarily ended by the outside of a document being shown me stating that the papers had been withdrawn by Samuel Hunt, thus agreeing with the statement made by him in Miss. Doc. 58, that they had been stolen from his desk while the committee were examining the claim.

I found it very difficult to obtain the earlier documents. (p. xi) "Supply exhausted" being the answer that has long been given, but all can be looked up in the bound volumes.

When, at length, fairly started in my work I was disturbed by a rumor that Miss Carroll's papers, formerly placed on file at the War Department, were no longer to be found there. I set out as far as possible to investigate. Provided with an excellent letter of introduction to the Secretary of War I made my way, on March 6, 1891, to the vast building of the War Department and sent in my letter with a list of the documents I wanted to see. Miss Carroll's Military papers, given in the Miss. Doc. 58, and a list of letters from the same memorial by Wade, Scott, and Evans.

The permission being kindly accorded I was transferred to the Record office and told that the file should be ready for me on the following day.

Taking with me the Miss. Doc. 58, an unpublished manuscript of Miss Carroll's, and specimens of the handwriting of Wade and Scott, I punctually put in an appearance, was transferred to the office of the Adjutant General, and Miss Carroll's file produced for my inspection. I met with all possible courtesy and every facility for the examination. I found two of the papers on my list in her now familiar handwriting, and some others.

A letter to Secretary Stanton, of May 14, 1862, recommending the occupation of Vicksburgh and referring to Pilot Scott, stating that she had derived from him some of the important information which had lead to her paper to the War Department on Nov. 30, 1861, which had occasioned the change of campaign in the southwest and proved of such incalculable benefit to the national cause.

(p. xii) A paper of May 15th, 1862, advising that Memphis and Vicksburgh should be strongly occupied and the Yazoo river watched. Another letter to Stanton concerning her pamphlets and proposing to write another one in aid of Mr. Lincoln, unjustly assailed. There was a portion of a letter written in great haste from St. Louis. There was an interesting letter from Robert Lincoln when Secretary of War. A petition from a group of ladies, asking for information concerning Miss Carroll's services and several other documents, but most of the important papers on my list were not on the file.

After examining the papers for some time I asked to see the originals of the letters of Wade and Scott. I was told they were in another department and would take some time to look up, but a gentleman was politely detailed to conduct me there and look up the letters. I opened my Miss. Doc. 58 and pointed out the long list of letters of Mr. Wade's, on pages 23, 24, 25, and 26, and asked to see those first.

The gentlemen expressed his astonishment that, with such a document in my hand, I should ask for originals. He said that the documents printed by order of Congress were to all intents and purposes the same as the originals, as they were never so printed until those letters and papers had been examined and proved to be genuine. I asked if the printing was also a guarantee for Miss Carroll's papers as printed in that document, though we were now unable to find the originals. He replied assuredly it was; that I could positively rely upon all that had been so printed. (p. xiii) There was no going back upon the Congressional records. Other gentlemen came up and confirmed the statement.

Under these circumstances it seemed unnecessary to carry the investigation any further, so with thanks for the great friendliness and courtesy that I had met with I took up my precious Miss. Doc. 58 and departed with a slight intimation that if anything more should be needed they might have the pleasure of seeing me again.

The missing documents, after being on file for 8 years, were sent on one or more occasions from the War Department to the Capitol for examination by committees.

On page 30 of the Miss. Doc. 58 we learn the reason, on testimony of Wade and Hunt (keeper of the records), why they are there no longer.

For list of documents see pages 29 and 82.

On page 178 of the memorial of '78 Judge Evans, in one of the many repeated letters and statements of great interest that I have been obliged to omit for want of space, relates how he stood beside Miss Carroll in her parlor at St. Louis when she was gathering the information for the preparation of her paper to the War Department of November 30, 1861, and its accompanying map. He says, "I have a very distinct recollection of aiding her in the preparation of that paper, tracing with her upon a map of the United States, which hung in her parlor, the Memphis and Charleston railroad and its connections southward, the course of the Tennessee, the Alabama, and the Tombigbee rivers, and the position of Mobile Bay; and when Henry fell she wrote the Department, showing the feasability of going either to Mobile or Vicksburg."

In his testimony given on page 85 of Miss. Doc. 179, he says, "On Miss Carroll's return from the West she prepared and submitted to the deponent, for his opinion, the plan of the Tennessee river expedition, as set forth in her memorial. Being a native and resident of that part of the section and intimately acquainted with its geography, and particularly with the Tennessee river, deponent was convinced of the vast military importance of her paper, and advised her to lose no time in laying the same before the War Department, (p. xv) which she did on or about November 30, 1861. The accompanying map, rapidly prepared by Miss Carroll, was made on ordinary writing paper. An unpretentious map, but fraught with immense importance to the national cause.

Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott, the great railroad magnate and a man of remarkably acute mind, saw at a glance the immense importance of the plan; he hastened with it to Lincoln, and when her plan of campaign was determined on he studied her map with the greatest care before going West to consolidate the troops for the coming campaign.

The second map sent in with Miss Carroll's paper of October, 1862, when the army before Vicksburg was meeting with disastrous failure, was made on regular map paper, representing the fortifications at Vicksburg, demonstrating that they could not be taken on the plan then adopted and indicating the right course to pursue. Miss Carroll bought the paper for the map at Shillington's, corner of Four-and-a-Half street and Pennsylvania avenue; sketched it out herself with blue and red pencils and ink and took it to the War Department.

On page 24 of Miss. Doc. 58, Judge Wade writes:

"Referring to a conversation with Judge Evans last evening he called my attention to Colonel Scott's telegram announcing the fall of Island No. 10 in 1862 as endorsing your plan, when Scott said, 'the movement in the rear has done the work.' I stated to the Judge, as you and he knew before, that your paper on the reduction of Vicksburg had done the work on that place, after being so long baffled (p. xvi) and with the loss of so much life and treasure by trying to take it from the water; that to my knowledge your paper was approved and adopted by the Secretary of War and immediately sent out to the proper military authority in that Department."

On April 16, 1891, by permission of the kindly authorities of the War Department, search was made in the office of the Chief Engineer to see if, by chance, these maps might have come to the War Department. No trace or record was found and it seemed to be agreed that, considering the circumstances of extreme secrecy attending the inauguration of the campaign, it was unlikely that they should come there. Time, which so often corroborates the truth, may possibly bring those maps to light. At present I cannot trace them.

It is proposed to follow this volume with another, entitled "Civil War Papers in Aid of the Administration," by Anna Ella Carroll, with notes by the author.

ancestry and old plantation life.

In looking at the map of Maryland we find that the configuration of the State is of an unusual character. The eastern portion is divided through the middle by the broad waters of Chesapeake Bay, leaving nine counties with the State of Delaware on the long stretch between the Chesapeake, Delaware Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean. Of late years the great tide of population has set toward the western side of Chesapeake Bay, leaving the widely divided eastern counties in a comparatively quiet and primitive condition. But in the earlier history of our country these eastern counties, with easy access to the Atlantic Ocean, were of greater comparative importance to the State, and were a Center of culture and of hospitality. It was in Somerset, one of the two southernmost of these eastern counties, that Sir Thomas King, coming from England about the middle of the eighteenth century, purchased an extensive domain.

Landing first in Virginia with a group of colonists, he there married Miss Reid, an English lady also highly connected and of an influential family. The estate which he subsequently purchased in Maryland embraced several plantations, extending from the county road back to a creek, a branch of the Annemessex river, then and since known as King's creek.

(p. 002) Standing well back and divided from the county road by extensive grounds, Sir Thomas King built Kingston Hall, a pleasant and commodious residence. An avenue of fine trees, principally Lombard poplars and the magnificent native tulip tree, formed the approach to the Hall, and its gardens were terraced down to the creek behind.

On one of the outlying plantations Sir Thomas King also established the little village of Kingston, of which he built and owned every house. He brought hither settlers, but the little place did not thrive. Plantation life and proprietary ownership were not conducive to the growth of cities. As the old settlers died out the houses were abandoned, and the post office was removed to a corner of the Hall plantation, then known as Kingston Corner. A new settlement grew up there, and since emancipation has changed the conditions of life it has grown and thriven. It is now a promising little place of 250 inhabitants. It has assumed to itself the name of the older village and is known as Kingston on the present maps.

At the Hall Sir Thomas King established his family residence. Here he lived and here his wife died, leaving but one child, a daughter, heiress to these wide estates, the future mother of Governor Thomas King Carroll and the grandmother of Anna Ella Carroll, whose interesting career is the subject of our present relation.

Through all the early history of Maryland the contests between Catholic and Protestant form one of its most conspicuous features. Early settled by Lord Baltimore, a Catholic proprietary, his followers were at once involved in a (p. 003) struggle with still earlier settlers at Kent Island, in the Chesapeake Bay, and the Protestants who followed, while condemning Catholicism as a rule of faith, associated it also with the doctrine of divine right and arbitrary rule. Bitter contests followed. The most active minds of the Colony enrolled themselves enthusiastically in the opposing parties.

St. Mary's, a little town on the western side of the Chesapeake, was the ancient capital of the State and the headquarters of Catholicism.

Sir Thomas King, on his side, was a staunch Presbyterian. This household was strictly ruled in conformity to his faith, and by liberal contribution and personal influence he was largely instrumental in building the first Presbyterian meeting-house, at the little town of Rehoboth, a few miles from his own domain, a great barn-like structure of red brick, which remains to this day. The marriage of Miss King with her cousin, young Mr. Armstead, of Virginia, the ward of Sir Thomas King, was an event that had been planned for in both families, and was looked forward to with great satisfaction on all sides.

One may well imagine, then, the consternation which ensued to the proprietor of the Hall, to his relatives and friends, and all the neighbors of that staunch Presbyterian region, when Colonel Henry James Carroll, of St. Mary's, of the old Catholic family of the noted Charles Carroll, and himself a Catholic by profession, came across the waters of the Chesapeake, courting the only daughter of Sir Thomas King, the heiress to all these estates and the reigning belle of the county.

(p. 004) In vain was the bitter opposition of father and friends. The willful young heiress insisted on giving to the handsome officer from St. Mary's the preference over all her other admirers. It may be that a reaction from the strict rules and the severe tenets of her education gave to this young scion of another faith an additional charm. However that may be, love won the day.

The father was compelled to yield, and the young heiress became the wife of the intrepid Colonel Henry James Carroll. It could hardly have been expected that Sir Thomas King should associate with himself under the same roof a son-in-law of principles so opposed to his own; but he established the young couple on the adjacent estate of Bloomsborough, which he also owned, and here their little son, Thomas King Carroll, first saw the light of day.

The old proprietor, in his great empty hall, coveted this little grandson and proposed to adopt him as his own child and make him the heir to all his estates.

In course of time a younger son, Charles Cecilius Carroll, was born to the Bloomsborough household, the grandfather's proposition was accepted, and little Thomas King Carroll, then between five and six years of age, became an inmate of Kingston Hall and the object of Sir Thomas King's devoted affection and brightest hopes.

Governor Carroll, in after times, used to relate to his children how they spent the winter evenings alone in the old Hall. His grandfather, in his spacious armchair, on one side of the open hearth, with a blazing wood fire and tall brass andirons; the little boy, in a low chair, on the (p. 005) opposite side, listening to the tales that his grandfather related of ancient times and heroic deeds. By these means Sir Thomas King strove to amuse his youthful heir and to train his mind to high principles and brave aspirations. But Sunday must have been a terrible day to the little boy, attending long services in the red brick meeting-house and occupying himself as he best could between whiles with the old English family Bible, with pictures of devils and lakes of fire and brimstone, calculated to inspire his youthful mind with horror and alarm.

At an early age the young heir was sent to college, to the Pennsylvania University at Philadelphia, then the most famous seat of learning for those parts. Here he graduated with distinguished honors, at the age of seventeen. Among his classmates and intimate friends were Mr. William M. Meredith, of Philadelphia; Benjamin Gratz, of St. Louis, and the father of Mr. Mitchell, the author of Ike Marvel.

Returning to Maryland, Thomas King Carroll began the study of law with Ephraim King Wilson, who had been named after Sir Thomas King. He was the father of the late United States Senator for Maryland. His studies being completed, arrangements were made to associate him as partner with Robert Goodloe Harper, the son-in-law of Charles Carroll, of Carrollton, in his lucrative law practice, and a house was engaged for his future residence in Baltimore.

During the studies of Thomas King Carroll, his aged grandfather, Sir Thomas King, having died, Colonel Henry James Carroll and his family were residing at Kingston Hall and managing the estate for the young heir.

(p. 006) An old friend of the family was Dr. Henry James Stevenson, one of the prominent physicians of Baltimore. Dr. Stevenson had come over formerly as a surgeon in the British army. He had married in England Miss Anne Henry, of Hampton. Settling in Baltimore, he acquired a large estate, then on the outskirts, now in the center of Baltimore. On Parnassus Hill he built a very spacious and handsome residence. During the Revolutionary War Dr. Stevenson remained loyal to his British training and was an outspoken Tory. The populace of Baltimore were so incensed against him that they mobbed his residence, threatening to destroy it. The Doctor showed his military courage by standing, fully armed, in his doorway and threatening to shoot the first man who attempted to enter. The mob were so impressed by his determined attitude that they finally retired, leaving the owner and his property uninjured. Dr. Stevenson afterwards became much beloved through his devotion and care, bestowed alike on the wounded of both armies. He became noted in the profession from his controversy with Dr. Benjamin Rush, of Philadelphia, the one advocating and the other opposing inoculation for small-pox. Dr. Stevenson was so enthusiastic that he gave up, temporarily, his beautiful residence as a hospital for the support of his theory.

An ivory miniature in a gold locket, now in possession of Miss Carroll, represents Dr. Stevenson in his red coat and white waistcoat, and at the back of the locket there is a picture of Parnassus Hill, crowned by the Doctor's residence, with a perpendicular avenue straight up hill, and a (p. 007) negro attendant opening the gate at the foot for Dr. Stevenson, mounted on his horse and returning home. It is a very quaint and valuable specimen of ante-revolutionary art.

The daughter of this valiant doctor was a beautiful and accomplished girl, Miss Juliana Stevenson. She is described as having very regular features, a complexion of dazzling fairness, deep blue eyes, and auburn hair flowing in curls upon her shoulders. She was a good musician, playing the organ at her church, and educated carefully in every respect. Her knowledge of English history was considered something phenomenal.

Thomas King Carroll early won the affections of this lovely girl, and they were married by Bishop Kemp before the youthful bridegroom had completed his twentieth year.

Those that care for heraldry may be interested to know that at Baltimore may be seen the eight coats-of-arms belonging to the King-Carroll family, of which Miss Anna Ella is the eldest representative.

When the question came of Miss Stevenson leaving home, her especial attendant, a bright colored woman, had been given her choice of remaining with Dr. Stevenson's family or accompanying her mistress. The poor woman was greatly exercised in choosing between conflicting ties.

Mrs. Carroll was accustomed to describe to her children, with much feeling, the scene which followed. Sitting in her room she heard a knock at the door and in rushed Milly, with her face bathed in tears, and throwing herself at Miss Stevenson's feet she exclaimed "Oh, mistis, I cannot, (p. 008) cannot, leave you!" It was a moment of deep emotion for both mistress and maid. Milly followed Mrs. Carroll to her new home and became the old mammy, the dear old mammy of all the Carroll children.

Her daughter Leah was born on the Kingston plantation, and then her granddaughter Milly, who in later times clung to the changing fortunes of the Carroll family, and is at this day a devoted attendant on her invalid mistress, Miss Anna Ella Carroll. A visitor to the modest home in Washington, now occupied by the Carroll sisters, is met at the door by the comely face and pleasant smile of this same faithful Milly. The life-long devotion of the affectionate "Mammy" illustrates one of the most touching features of the old plantation life; but the shadow of slavery was over it all. To follow the fortunes of her adored mistress, Mammy left behind her in Baltimore her husband, a free colored man. But what was the marital relation to a slave! The youthful couple set out on a wedding tour, but were unexpectedly recalled by the sudden death of Colonel Henry James Carroll. It was necessary for his son to return at once and take possession of his inheritance.

The coming home of the proprietor and his youthful bride was a great event at Kingston Hall. There were at that time on the plantation 150 slaves, besides the children. They are described as a fine and stalwart people, looking as if they belonged to a different race from the colored people that we now meet with in cities. They seemed like a race of giants. The men were usually as much as six feet in height, and broad and muscular in proportion. All these (p. 009) numerous dependents were drawn up in lines on the long avenues, dressed in their livery of green and buff, and must have presented an imposing appearance as the stately family carriage was seen approaching through the long vista of fine old trees. The arrival was heralded by a roar of welcome and demonstrations of joy.

And thus the youthful couple took possession of the home that was to be the scene of so many joys and so many sorrows, ending in troublous times that completely changed the existing order of things, and which witnessed the conclusion of the reign of the Kings and the Carrolls at Kingston Hall.

Shortly after his return with his bride Thomas King Carroll was elected to serve in the Legislature. He only attained the requisite age of 21 years on the day before he took his seat. His birth-day was celebrated at Kingston Hall after the old English fashion, and he was feted and toasted and received congratulations on all sides. It is said that he was the youngest member ever elected to the Legislature.

Thomas King Carroll commenced life not only with wide social advantages, but with great natural gifts. He was striking in appearance, and of so graceful and dignified a demeanor that it is said that he never entered a crowd without a movement of respect and appreciation showing the impression that he created.

He was a good orator and of unimpeachable integrity and lofty character. This was early exemplified when as still very youthful he was sent to represent his county at a political (p. 010) caucus in Baltimore. The question of raising money for the approaching campaign came up, and he was asked in his turn how much would be needed for his county of Somerset. He arose and said: "With all due deference, Mr. President, not one cent. We can carry our county without any such aid!" There was a general laugh, and Robert Goodloe Harper, who was present, said, "Very well, young gentleman, you will tell a different tale a few years hence." He went home and related the proceedings to his constituents, who applauded his answer, and that year Somerset was the banner county of the State.

The early years succeeding the marriage were years of peace and prosperity.

The young bride won all hearts by her beauty and the sweetness of her disposition.

In time a lively group of children filled the old Hall with life and gayety.

Thomas King Carroll, like many another Maryland planter, was fully convinced that in itself slavery was wrong. The early settlers of Maryland would gladly have excluded it, but the institution was forced upon them by the mother country, the English monarch and his court deriving large incomes from the sale of slaves and canceling every law made by the early settlers to prevent their introduction into the colony. Slavery had now become a settled institution, on which the whole social fabric was built, and individual proprietors, however they might disapprove of the system, could see no way to change it. All that Thomas King Carroll knew how to do was to seek as far as (p. 011) possible the happiness and welfare of his slaves, and slavery showed itself on the Kingston plantation in its mildest and most attractive form.

Not much money was made usually upon plantations, but everything was produced upon the estate that was needed to feed and clothe the great group of dependents. And this was the state of things at Kingston Hall.

There was Uncle Nathan, the butler, whose wife was Aunt Susan, the dairywoman; Uncle Davy, the shoemaker; Saul, the blacksmith; Mingo, the old body servant of Colonel Carroll; Fortune, the coachman, etc., etc.—all very powerful men.

Every trade was represented upon the estate. There were blacksmith shops; there were shoemakers, tanners, weavers, dyers, etc. All the goods worn by the servants, male and female, were manufactured on the place. The wool was sheared from the sheep, and went through every process needed to produce the linsey-woolsey garments of men and women. The women were allowed to choose the colors of their dresses, and the wool was dyed in accordance with their tastes. Two of these dresses were allowed for a winter's wear, and each woman was furnished with a new calico print for Sundays.

There were few local preachers among them at that time, but two were noticeable during the childhood of the Carroll children, Ethan Howard and Uncle Saul. And there was an Uncle Remus, too, in Fortune, the coachman, who told the children the stories of Brer Rabbit and the Tar-baby quite as effectively as the Uncle Remus of our popular magazines.

(p. 012) The servants had their own rivalries and class distinctions. One portion of the house servants prided themselves as being the old servants—born on the place. Another group plumed themselves as having come in with the "Mistis," and having seen outside regions and a wider range of life. But all the house servants considered themselves vastly superior to the field hands and treated them with condescension.

The house servants, though slaves, in fact, were absolute despots in their own department. The Carroll children would not have dared to touch a knife or a fork without the permission of the butler, and if they had attempted to enter the cellar or the dairy without leave from their respective guardians a revolutionary war would have been the result.

Mammy, too, was the absolute ruler over every shoe and stocking, and was expected under all circumstances to be responsible for every article of the children's toilet.

The largest quarter devoted to the slaves was a great circular structure, with a central hall surrounded by partitions, giving to each field hand a separate sleeping berth. The hall in the center was devoted to those who were old or unfitted for work, and here the young children were deposited while their parents were pursuing their tasks, and they were expected to wait upon the "Grannies" and be cared for in return.

Behind this central apartment was one in which the food was prepared, and there was a great hand-mill, where the corn was ground for the daily use.

(p. 013) The children at the Hall were seldom allowed to enter these quarters, but were occasionally granted permission to go there when delicacies for the sick or new caps and dresses for the babies were furnished from the Hall.

There were also quarters for the married slaves, each family having its little cottage and garden, which it was allowed to cultivate on its own account, and great was the pride of its occupants if by dint of especial care they could raise the spring vegetables earlier than in the master's garden, and carry them up to the Hall in triumph. There they always found a customer ready to purchase their produce. Every Monday morning rations were given out for a week by the overseer and they were cooked by the families in their own quarters.

The hours of work were moderate, and on Saturday they had a half holiday.

Sometimes there were parties and merry-makings at the negro quarters. On great occasions, such as the marriage of a house servant, the family at the Hall, by their presence, gave dignity to the festivities, and inwardly they greatly enjoyed the fantastic scene.

At Kingston Hall open house was kept, and numerous visitors and entertainments made life gay for the children, who grew up in an atmosphere of ease and hospitality, little anticipating the vicissitudes of the future and the stormy and heart-rending times in which their country was about to be involved.

childhood and early life — miss carroll's youthful letters to her father — religious tendencies — letters from dr. robert j. breckenridge — sale of kingston hall — early writings — letter of hon. edward bates — breaking out of the civil war — preoccupation in military affairs.

On August the 29th, 1815, Anna Ella Carroll was born, at Kingston Hall. By this time a little brick Episcopal church had also been built at Rehoboth, but the congregation was too small to support a resident clergyman, and it had to alternate with other churches in its services. At this infant church, in due course of time, Anna Ella was christened by the Rev. Mr. Slemmonds. She was the eldest child, and thenceforth the pride of her distinguished father, who viewed with delight her remarkable intelligence, and early made her his companion in the political interests in which he took such an active part. It soon became evident that this was a child of decided and unusual character. When but three years old she would sit on a little stool at her father's feet, in his library, listening intently as he read aloud his favorite passages from Shakespeare.

KINGSTON HALL—Birth Place of Anna Ella Carroll.

All Mr. Carroll's children were so drilled in Shakespeare that there was not one of them who could not, when somewhat (p. 015) older, repeat long passages by rote, and they made the rehearsal of scenes from Shakespeare's plays one of their favorite amusements. Anna Ella showed no taste for accomplishments; cared neither for dancing, drawing, music, or needlework. She used to boast to her sisters that she had made a shirt beautifully when ten years old; but they would smile at the idea, as they had never seen her handle a needle and could associate her only with books.

These were to her of absorbing interest, and books, too, of a grave and thoughtful character. Alison's History and Kant's Philosophy were her favorite reading at eleven years of age. She read fiction to some extent, under her father's direction; but, with the exception of Shakespeare and Scott, she never cared for it. While other girls of her age were entranced by Sir Charles Grandison and fascinated by the heroes of Bulwer's earlier novels, she turned from them to read Coke and Blackstone with her father, and followed with him the political debates and discussions of the day. She studied with lively interest the principles and events which led to the separation of the Colonists from the Mother Country, and buried herself in theological questions. At a very early age her letters bore reference to the gravest subjects. Imagination was never prominent; her mind was essentially analytical. Pure reason and clear consecutive argument delighted her, and works of that nature were eagerly sought by her.

Her life passed largely in her father's excellent library, which was well stocked with classic works, both history, biography, philosophy, and poetry, and her education was to him a constant delight.

(p. 016) Miss Carroll's early associates were the children of the neighboring proprietors, the Handys, the Wilsons, the Gales, the Henrys, etc., and she early made acquaintance with the distinguished men who where her father's associates.

Mr. Carroll continued to serve in the Legislature until elected Governor of Maryland, in 1829. On this occasion he received an interesting letter from Charles Carroll, of Carrollton, congratulating him and expressing his pride and gratification at the event. When Governor Thomas King Carroll went to Annapolis, in performance of the duties of his office, he was accompanied by Mrs. Carroll, with the younger children and a group of servants under the superintendence of the invaluable Mammy. Mrs. Carroll, by her beauty and accomplishments, was well fitted to adorn her station. When the weather became warm she returned with her children to Kingston Hall.

The following charming letters from Miss Carroll, then a girl of fourteen, show the tenderness of the relation between father and child, and at how early an age she interested herself in politics and entered into the questions of the day:

Kingston Hall, Jan. 20, 1830.

My Precious Father:

My dearest mother received your letter on Monday, and we were all happy to know you had arrived safely at the seat of government, although the Annapolis paper had previously announced it.

Oh! my dear father, if I could but see you! I miss you—we (p. 017) all miss you—beyond measure. The time passes tediously without you.

I have just read Governor Martin's last message.[1] I think it quite well written. I wondered to see it published in the Telegraph [an opposition paper, I suppose]. I am anxious to see what the Eastern papers say of your election. Please, dear father, when anything relating to your political action is published, whether in the form of a message, in pamphlet, or in newspaper, do not fail to let us have them. I read with so much pride your letter in the Annapolis paper. It merits all the distinction and fame it has brought you. Too much could not be said in praise of my noble father. Dr. K—— was here to-day. He says they feel "quite exalted" to be so near neighbors to a Governor.

When do you think the Legislature will rise? But I must not write on political subjects only. Brother is delighted with his new horse. The little children are begging dearest mother to write you for them. May every blessing attend you, my precious father. Be sure and write me a long letter.

Your devoted daughter,

A. E. Carroll.

Kingston Hall, Feb. 17, 1830.

My Beloved Father:

Again we are disappointed in your arrival home! and how disappointed no tongue can tell. Dearest mother thought it possible you might come on a little visit, even if the Legislature did not rise.[2] You said in your last letter to me that this was "probable." Why did you not say (p. 018) "certain?" Then I would rejoice, for when my father says a thing is certain, I know it is certain. I am happy to tell you that I am much better; have had a long and tedious spell. I would lie for hours and think of you away from me, and if I had not the kindest and tenderest mother to care for me and for us all, what should we do. I understand that your appointments have not been generally approved by the milk-and-water strata of the party, of course, for no thorough Jackson man would denounce, even if he did not approve. It is my principle, as well as that of Lycurgus, to avoid "mediums"—that is to say, people who are not decidedly one thing or the other. In politics they are the inveterate enemies of the State. I hear there has been a committee appointed to visit you on your return to the Hall and present a petition for the removal of some whom you have recently appointed. They call themselves reformers. I want reform, too, even in court criers, but to be forever reforming reform is absurd. I know whatever you do is right, and needs no reform, my wisest and dearest of fathers.

Write as soon as you can to your loving child,

A. E. Carroll.

Mrs. Carroll was a devoted member of the Church of England, as was natural in the daughter of staunch Dr. Stevenson.

As there were no Sunday schools in those days, Mrs. Carroll gathered her children around her on Sunday afternoons and drilled them in the church catechism until it was as familiar to them as their A B C; but Anna Ella always inclined to the Westminster Confession and the tenets in which her father's childhood had been so rigorously educated.

(p. 019) When about fifteen Miss Carroll was sent to a boarding school, at West River, near Annapolis, to pursue her studies with Miss Margaret Mercer, an accomplished teacher.

Thomas King Carroll, at the same age, had been sent to the University of Pennsylvania, and afterward to the law school; but for this girl of gifts so remarkable, and of a character so decided, the best thing that the world of those times offered was a young ladies' boarding school of the olden time. Well it was for her and her country that her exceptional position as the cherished daughter of a man of such education and talent, occupied with political affairs, secured for her an education that would otherwise have been unattainable to her.

However, she made the best possible use of such education as a ladylike school permitted, was noted for her intelligence, and made many friends; but her true education began and continued with Governor Carroll at home.

Miss Carroll had early shown an intense interest in moral and religious questions, following her father's views on these subjects. She became interested in the ministrations of Dr. Robert J. Breckenridge, of Kentucky, then settled over a Presbyterian church in Baltimore.

Dr. Breckenridge was the uncle of John C. Breckenridge, afterward one of the leading secessionists, utterly opposed to his uncle in political views, and one of the candidates for the Presidency in 1860.

Dr. Robert J. Breckenridge was a valued friend of Governor Carroll.

Miss Anna Ella became a communicant and earnest (p. 020) member of his church, and a mutual friendship arose, terminated only by the death of the aged minister, who has left on record his high appreciation of the mental abilities and the great services afterward rendered by his remarkable parishioner.

We will give in part two letters from this excellent man to Miss Carroll, written from Kentucky in after years. For want of space we must greatly shorten them.

Danville, Ky., December 6, 1864.

My Excellent Friend:

It is very seldom I have read a letter with more gratification than yours of November 29th. How kind it is of you, after so many events, to remember me; and how many people and events and trials and enjoyments, connected with years of labor, rush through my heart and my brain as you recall Maryland and Baltimore so freshly and suddenly to me; and how noble is the picture of a fine life, well spent, which the modest detail of some of your efforts realizes to me. It is no extravagance, not even a trace of romance; it is a true enjoyment, and deeply affecting, too, that you give me in what you recount and what is recalled thereby. For what is there in our advanced life more worthy of thankfulness to God than that our former years were such that if we remember them with tears they are tears of which we need not be ashamed. My life during the almost twenty years since I left Maryland has been, as the preceding period had all been, a scene of unremitting effort in very many ways; and now, if the force of invincible habit permitted me to live otherwise, I should hardly escape by any other means a solitary if not a desolate old age. Solitary, because of a numerous family all, except (p. 021) one young son, are either in the great battle of life or in their graves. Desolate, because the terrible curse which marks our times and desolates our country has divided my house, like thousands of others, and my children literally fight in opposite armies and my kindred and friends die by each other's hands. There is no likelihood, in my opinion, that our Legislature will send me to the Senate of the United States; and will you wonder if I assure you that I have never desired that they should. Was it not a purer, perhaps a higher, ambition to prove that in the most frightful times and through long years a simple citizen had it in his power by his example, his voice and his pen, by courage, by disinterestedness, by toil, to become a real power in the State of himself; and have not you, delicately nurtured woman as you are, also cherished a similar ambition and done a similar work, even from a more difficult position? * * * I beg to be remembered in kind terms to your father, and that you will accept the assurances of my great respect and esteem.

Robert J. Breckenridge.

Danville, Ky., April 27, 1865.

My Dear Miss Carroll:

* * * You will easily understand how much I value the good opinion you express of my past efforts to serve our country, and of my ability to serve it still further; and it is very kind of you to report to me with your approbation the good opinion of others, whom to have satisfied is in a measure fame. * * * Many years ago, without reserve and with a perfect and irrevocable consecration, I gave myself and all I had to Him, and have never, for one moment, regretted that I did so. The single principle of my existence, from that day to this, has been to do with my might what it was given to me to see it was God's will (p. 022) I should do. You see, my dear Miss Carroll, that I, who never sought anything, am not now capable of seeking anything, nor even permitted to do so; and, on the other hand, that I, who never refused to undertake any duty, am not allowed now to hesitate, if the Lord shows me the way, nor permitted to refuse what my country might demand of me. This is all I can say—all I have cared to say for nearly my whole life. I would not turn my hand over to secure any earthly power or distinction. I would not hesitate a moment to lay down my life to please God or to bless my country.

Mr. Lincoln was my personal friend and habitually expressed sentiments to me which did me the highest honor.

It gives me pleasure to learn that you propose to publish annals of this revolution, and I trust you will be spared to execute your purpose.

Make my cordial salutations to your father and accept the assurance of my high respect and esteem.

Your friend, &c.,

R. J. Breckenridge.

Miss Carroll was very pleasing, with a fine and intelligent face, an animated and cordial manner, and great life and vivacity, roused into fire and enthusiasm on any topic that appealed to her intellect and her sympathies. Naturally, in so favorable a social position and with such gifts, she received early in life much attention and had offers of marriage from many distinguished parties; but she never seemed inclined to change her condition or to give up the beloved companionship of her father. A literary life and his congenial presence seemed to be all-sufficient for her, and she remained his devoted companion until his death, in (p. 023) 1873, when she also, the child of his youth, was well advanced in life.

After Governor Carroll's term of office had expired he returned to his estate, and shortly after he was waited upon by a deputation, who had been sent to enquire if he would accept a nomination as United States Senator. But at that time Mrs. Carroll was dangerously ill. His extensive plantation and group of children required his presence, and he declined to serve. He was devoted to his wife, and their marriage was one of unbroken harmony until her death, in 1849. Governor Carroll devoted himself thereafter to the necessities of his family and estate.

Anna Ella Carroll frequently visited her friends at Washington, and early commenced an extended relation with the press, writing usually anonymously on the political subjects of the day. A friend of her father, Thomas Hicks, considered that he owed his election as Governor of Maryland largely to the articles which she contributed in his favor, and he retained through life a strong personal friendship and high admiration for her intellectual powers. At his death he left her his papers and letters, to be edited by her—a labor prevented by her subsequent illness. In 1857 Miss Carroll published a considerable work, entitled "The Great American Battle," or Political Romanism, that being the subject of immediate discussion at that time. This work was compiled from a series of letters contributed by her to the press, and her family knew nothing of the project until she surprised them by the presentation of the bound volume.

(p. 024) Old Sir Thomas King would certainly have been greatly gratified if he could have known how vigorously his great-granddaughter was to uphold the banner of religious and political freedom. This work was accompanied by an excellent portrait of the authoress in the prime of life, which we here reproduce for our present readers.

In the following year Miss Carroll published another considerable work, entitled "The Star of the West," relating to the exploration of our Western Territories, their characteristics, the origin of the National claims, and our duties towards our new acquisitions, and she urged the building of the Pacific railroad. This seems to have been one of her most popular works, as it went through several editions, and greatly extended her acquaintance with leading men.

The following letter, written by the Hon. Edward Bates, is very descriptive of Miss Carroll and evinces the admiration and esteem which she inspired among those best fitted to appreciate her high character, her uncommon cultivation, and natural gifts.

Washington, D. C., October 3, 1863.

To Hon. Isaac Hazlehurst, of Philadelphia.

My Dear Sir: I have just received a note from Miss Anna Ella Carroll, of Maryland, informing me she is going to Philadelphia, where she is a comparative stranger, and desiring an introduction to some of the eminent publicists of your famous city.

I venture to present her to you, sir, first, as an unquestionable (p. 025) lady of the highest personal standing and family connection; second, as a person of superior mind, highly cultivated, especially in the solids of American literature, political history, and constitutional law; third, of strong will, indomitable courage, and patient labor. Guided by the light of her own understanding, she seeks truth among the mixed materials of other minds, and having found it, maintains it against all obstacles; fourth and last, a writer fluent, cogent, and abounding with evidence of patient investigation and original thought.

I commend her to your courtesy, less for the delicate attentions proper for the drawing room than for the higher communion of congenial students, alike devoted to the good of the Commonwealth.

With the greatest respect, I remain, sir, your friend and servant.

Edward Bates.

As time went on, Thomas King Carroll, now advanced in years, many of his children married and scattered, began to find his estate and great group of dependents a burdensome and unprofitable possession.

Under a humane master, unwilling to sell his slaves, they were apt to increase beyond the resources of the plantation to sustain them. Ready-money payment was not the general rule upon plantations. Abundance of food was produced, but money was not very plentiful when markets were distant and trade very limited.

It was not unusual for debts to accumulate and even to be handed down from father to son. The creditors rather favored this state of things, as the debt drew interest. As long as there were plenty of slaves, their ultimate payment (p. 026) was secure whenever they chose to press for it. If the money was not then forthcoming, their redress was certain—a descent followed of that brutal intermediary, "the nigger dealer," loathed and dreaded alike by master and servant. A sufficient amount of the human property was speedily secured and driven off for sale to satisfy the creditor. To the slave, torn from his home and his life-long ties, it was despair. To the master's family, often a bitter grief. They might shut themselves up and weep at the outrage, but they were powerless in the face of an inexorable system. To the master, therefore, as the slaves increased, there could often be no alternative between ruthless sale and financial ruin. Thomas King Carroll, honorable, humane, unwilling to sell his slaves, immersed during the best years of his life in political affairs, found in later years his burdens increasing, and his kindness of heart had involved him also in some especial difficulties. He had on several occasions allowed his name to be used as security for friends in difficulty. Two or three of these debts remained unpaid and the responsibility came upon him. One especially, of an unusually large amount, involved him in embarrassment which led him to determine on the sale of his plantation. A neighbor and intimate friend, Mr. Dennis, was desirous to purchase, and very sorrowfully Thomas King Carroll came to the resolution to give up his ancestral home. As he was accustomed to say, he loved every corner and every stone upon the place, but the burden had become too great for his declining strength.

The sale was effected and Mr. Carroll removed to Dorchester (p. 027) county, on the eastern side of the Chesapeake, with his unmarried children, and here he died, in 1873, in his 80th year.

Governor Carroll is described in the annals of the State as "one of the best men Maryland has ever produced," a man of character unsullied and of lofty integrity.

At the breaking out of the civil war Mr. Carroll was already an elderly man. At first his sympathies were with his own section, but after the attack on Fort Sumter they were steadily enlisted for the National cause, though he foresaw that its triumph would lead to the destruction of his own fortunes and those of his children.

Most of the slaves had been left on the plantation, but some had always been considered the especial property of each of his children.

Thus Anna Ella Carroll had her own group. At the very outset of the war she fully realized that slavery was at the root of the rebellion, and she at once liberated her own slaves and devoted her time, her pen, and all her resources to the maintenance of the National cause. She immediately commenced a series of writings of such marked ability that they speedily attracted the attention of Mr. Lincoln and the Administration. Governor Hicks, too, placed in a situation of unusual difficulty, turned to his able friend for consultation and for moral and literary support.

Jefferson Davis, who was aware of Miss Carroll's great literary and social influence, wrote to her early in the secession movement adjuring her to induce her father to take sides with the South.

(p. 028) "I will give him any position he asks for," wrote Mr. Davis.

"Not if you will give him the whole South," replied Miss Carroll.

A visitor to her in 1861 says: "Her room was lined with military maps, her tables covered with papers and war documents. She would talk of nothing but the war. Her countenance would light up most radiantly as she spoke of the Union victories and the certainty that the great Nation must win an ultimate success."

When fresh news from the army came in she would step up to one of her charts and, placing a finger on a point, she would say: "Here is General ——'s detachment; here is the rebel army; such and such are the fortifications and surrounding circumstances; and she would then begin thoughtfully to predicate the result and suggest the proper move."

We will give a sketch of the situation in the early days of the secession movement, mainly in the words of Miss Carroll's own able account, afterwards published by order of Congress.

(p. 029) List of Documents in Relation to Services Rendered by Anna Ella Carroll, to be Found in the Descriptive Catalogue of the Congressional Library.

(Descriptive Catalogue, page 911.)

Petition for compensation for services. Anna Ella Carroll. March 31, 1870. Senate Mis. Doc. No. 100, 41st Congress, 2d session.

(Catalogue, page 928.)

Report on memorial of Miss Carroll. Senator Howard. February 2, 1871. Senate report No. 339, 41st Congress, 3d session.

(Catalogue, page 962.)

Memorial for payment of services. June 8, 1872. Senate Mis. Doc. No. 167, 42d Congress, 2d session, vol. II.

(Catalogue, page 1058.)

Petition for compensation for services. Anna Ella Carroll. February 14, 1876. House Mis. Doc. No. 179, 44th Congress, 1st session, vol. IX.

(p. 030) (Catalogue, page 1099.)

Memorial of Anna Ella Carroll. October 22, 1877. Senate Mis. Doc. No. 5, 45th Congress, 1st session, vol. I.

(Catalogue, page 1128.)

House of Representatives. Mis. Doc. No. 58, 45th Congress, 2d session. Claim of Anna Ella Carroll. Memorial of Anna Ella Carroll, of Maryland, praying for compensation for services rendered to the United States during the late civil war. May 18, 1878.

(Catalogue, page 1149.)

Report on claim of Anna Ella Carroll. Senator Cockrell February 18, 1879. Senate Report No. 775, 45th Congress, 3d session, vol. II.

(Catalogue, page 1241.)

Report of claim of Anna Ella Carroll. Representative E. S. Bragg. March 3, 1881. House report No. 386, 46th Congress, 3d session, vol. II.

Note.—Most of these only to be seen by consulting the bound volumes in the Congressional Library.

(All the following letters, reports, etc., concerning Miss Carroll's literary and military services are reproduced from these Congressional documents.)

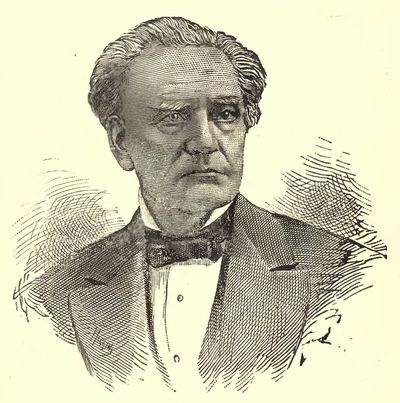

Thomas A. Scott

rise of the secession movement — the capital in danger — miss carroll's literary labors for the cause of the union — testimonials from eminent men.

"On the election of Mr. Lincoln, in 1860, the safety of the Union was felt to be in peril and its perpetuity to depend on the action of the border slave States, and, from her geographical position, especially on Maryland.

In the cotton States the Breckenridge party had conducted the canvass on the avowed position that the election of a sectional President—as they were pleased to characterize Mr. Lincoln—would be a virtual dissolution of the "compact of the Union;" whereupon it would become the duty of all the Southern States to assemble in "sovereign convention" for the purpose of considering the question of their separate independence.

In Maryland the Breckenridge electors assumed the same position, and as the Legislature was under the control of that party, it was understood that could it assemble they would at once provide for a convention for the purpose of formally withdrawing from the Union. The sessions, however, were biennial, and could only be convened by authority of the Governor. It therefore seemed for the time that the salvation of the Union was in the hands of (p. 032) Governor Hicks. Although he had opposed the election of Mr. Lincoln and all his sympathies were on the side of slavery, his strong point was devotion to the Union. With this conviction, founded upon long established friendship, Miss Carroll believed she might render some service to her country, and took her stand with him at once for the preservation of the Union, come weal or woe to the institution of slavery.

Governor Hicks had been elected some three years before as the candidate of the American party, and to the publications Miss Carroll had contributed to that canvass he largely attributed his election. It was therefore natural that when entering on the fierce struggle for the preservation of the Union, with the political and social powers of the State arrayed against him, that he should desire whatever aid it might be in her power to render him.

A few days after the Presidential election Miss Carroll wrote Governor Hicks upon the probable designs of the Southern leaders should the cotton States secede, and suggested the importance of not allowing a call for the Legislature to be made a question. That she might be in a position to make her services more effective, she repaired to Washington on the meeting of Congress in December, and soon understood that the Southern leaders regarded the dissolution of the Union as accomplished.

The leading disunionists from Maryland and Virginia were on the ground in consultation with the secession leaders in Congress, and the emissaries from the cotton States soon made their appearance, when it was resolved to make (p. 033) Maryland the base of their operations and bring her into the line of the seceding States before the power of the Democratic party had passed away, on the 4th of March, 1861.

Hence every agency that wickedness could invent was industriously manufacturing public opinion in Baltimore and all parts of the State to coerce Governor Hicks to convene the Legislature.

With Maryland out of the Union they expected to inaugurate their Southern Confederacy in the Capitol of the United States on the expiration of President Buchanan's term, on the 4th of March, and by divesting the North of the seat of Government and retaining possession of the public buildings and archives, they calculated with great confidence upon recognition of national independence by European powers. About the middle of December Miss Carroll communicated to Governor Hicks their designs on Maryland and suggested the propriety of a public announcement of his unalterable determination to hold Maryland to the Union.

After his address on the 3d of January, 1861, resolutions and letters from men and women endorsing his cause were received from Maryland and from all quarters of the United States.

Governor Hicks at that time was willing to abide by any terms of settlement that would save a conflict between the sections. He favored the compromise proposed by the border States committee, that slavery should not be forbidden, either by Federal or territorial legislation, south of (p. 034) 36° 30', and he was strongly inclined to base his action on the acceptance or rejection of the Crittenden resolutions by Congress.

On the 19th of January, 1861, he urged Miss Carroll to exert whatever influence she was able to induce Congress to adopt some measure of pacification; but she was soon satisfied that no compromise that Congress would adopt would be accepted by the cotton States, and, perceiving the danger should the Governor commit himself to any impossible condition, informed him on the 24th of January that the Crittenden proposition would by no possibility receive the sanction of Congress.

All efforts to move the steadfastness of the Governor having failed, the President of the Senate and Speaker of the House of Delegates issued their call to the people to act independently of him and elect delegates to a convention. This was a most daring and dangerous proceeding, and had the plan succeeded and a convention assembled they would immediately have deposed the Governor and passed an ordinance of secession. The Governor was powerless in such an emergency to defend the State against the revolutionary body, as the State militia were on their side and Mr. Buchanan had declared that the National Government could not coerce a sovereign State.

The gravity of the situation was appreciated by the Governor and the friends of the Union. Miss Carroll addressed articles through the press and wrote many letters to prepare the public mind in Maryland for the struggle. Fortunately the people (thus warned) failed to endorse this call; consequently (p. 035) the leading statesmen of the disunion party abandoned their cherished expectation of inaugurating their Government in the National Capitol.

Many of the conspirators, however, still sought to seize Washington and forcibly prevent the inauguration of the President elect on the 4th of March. The military organizations of the South were deemed sufficient for the enterprise, and a leader trained in the wars of Texas was solicited to lead them. The more sagacious of their party, however, discountenanced the mad scheme. They assured Miss Carroll that no attempt would be made to seize the Capitol and prevent the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln, so long as Maryland remained in the Union.

The ruthless assault upon the Massachusetts troops in Baltimore, as they were passing through on their way to Washington, on the 19th of April, with the antecedent and attendant circumstances, roused to the highest degree the passions of all who sympathized with the secession movement, and the mob became for the time being the controlling force of that city. So largely in the ascendant was it and so confident were the disunionists in consequence that they, without warrant of law, assumed the responsibility of issuing a call for the Legislature of Maryland to convene in Baltimore. Governor Hicks, fearing that the Legislature would respond to the call, and that if it did it would yield to the predominant spirit, give voice to the purpose of the mob, and adopt an act of secession, resolved to forestall such action by convening that body to meet at Frederick City, away from the violent and menacing demonstrations of Baltimore.

(p. 036) The Legislature thus assembled contained a number of leading members who were ready at once for unconditional secession. There were also others who, with them, would constitute a majority and would vote for the measure could they be sustained by public sentiment, but who were not prepared to give that support without that assurance. The field of conflict was, therefore, transferred from the halls of legislation to the State at large, and to the homes of their constituents, and there the battle raged during the summer of 1861. In that conflict of ideas Miss Carroll bore an earnest and prominent part, and the most distinguished men have given repeated evidence that her labors were largely instrumental in thwarting the secessionists and saving Maryland to the Union. The objective point of the labors of the disunion leaders was a formal act of secession, by which Maryland would become an integral portion of the Confederacy, not only affording moral and material aid to the Southern cause, but relieving the rebel armies in crossing the Potomac from the charge, which at that stage of the conflict the leaders were anxious to avoid, of ignoring their vaunted doctrine of State rights by invading the territory of sovereign States. With the usual arguments that were urged to fire the Southern heart and to reconcile the people to the extreme remedy of revolution, special prominence was given to what was stigmatized as the arbitrary and unconstitutional acts of President Lincoln. To place the people in possession of the true theory of their institutions and to define and defend the war powers of the Government were the special purposes of Miss Carroll's labors during these eventful months."

(p. 037) It would not be possible in the compass of this paper to set forth circumstantially all the important questions that arose in the progress of the war, in the discussion of which Miss Carroll took part; but it is proper to say that on every material issue, from the inception of the rebellion to the final reconstruction of the seceded States, she contributed through the newspapers, in pamphlet form, and by private correspondence to the discussion of important subjects. Governor Hicks bore the brunt of this terrible conflict, greatly aided by Miss Carroll's public and private support, and stimulated by such inspiring letters as the following:

Washington House,

Washington City, Jan. 16, 1861.

My Dear Governor:

I have for some days intended to write and express my cordial admiration and gratitude for the noble stand you have now taken in behalf of the Union by the public address issued on the 3d instant. An extended relation with the leading presses of the country has enabled me in a public and more efficient manner to testify to this and create a public opinion favorable to your course of patriotic action throughout the land. Many of the articles you have seen emanated from this source.

I feel it will be a gratification to you, in the high and sacred responsibilities which surround your position, to know from one who is incapable of flattering or deceiving you the opinion privately held in this metropolis concerning your whole course since the secession movement in the South was practically initiated.

(p. 038) With all the friends of the Union with whom I converse, without regard to section or party, your course elicits the most unbounded applause. I might add to this the evidences furnished from private correspondence, but you doubtless feel already the sympathy and moral support to be derived in this way. I am often asked if I think you can continue to stand firm under the frightful pressure brought to bear upon you. I answer, yes; that my personal knowledge enables me to express the confident belief that nothing will ever induce you to surrender while the oath to support the Constitution of your country and the vow to fulfill the obligations of your God rest upon your soul.

As a daughter of Maryland, I am proud to have her destiny in the hands of one so worthy of her ancient great name; one who will never betray the sacred trust imposed upon him. "When God is for us, no man can be against us," is the Christian's courage when the day of trial comes.

I shall continue to fight your battle to the end.

Your sincere friend,

A. E. Carroll.

Well might Governor Hicks say to her again and again, as in a letter to her in 1863: "Your moral and material support I shall never forget in that trying ordeal, such as no other man in this country ever went through."

A little further on, Governor Hicks writes as follows:

Annapolis, Md., December 17, 1861.

My Dear Miss Carroll:

In the hurry and excitement incident to closing my official relations to the State of Maryland I cannot find fitting (p. 039) words to express my high sense of gratitude to you for the kind and feeling manner in which you express your approval of my whole term of service in doing all in my power to uphold the honor and dignity of the State; but especially do I thank you for the personal aid you rendered me in the last part of my arduous duties.

When all was dark and dreadful for Maryland's future, when the waves of secession were beating furiously upon your frail executive, borne down with private as well as public grief, you stood nobly by and watched the storm and skillfully helped to work the ship, until, thank God, helmsmen and crew were safe in port.

* * * * * *

With great regard, I have the honor to be ever your obedient friend and servant.

T. H. Hicks.

Thus it was that, supported by Miss Carroll, this high-minded and sorely tried man held fast to the end. He went into the struggle a rich man, in a position of worldly honor and prosperity. He came out of it reduced in prosperity, having, like other faithful Southern Unionists, lost his worldly possessions in that great upheaval. Thenceforth he lived, and he died, comparatively a poor man, but one of the noble and faithful who had acted an immortal part in the salvation of his country. All honor to brave and true-hearted Governor Hicks of Maryland!

Thus by her powerful advocacy and influence Miss Carroll largely contributed to securing the State of Maryland to the Union and saving the National Capital, and her (p. 040) writings also had a great effect upon the border States. Besides her numerous letters and newspaper articles, she began writing and publishing, at her own expense, a remarkable series of war pamphlets, which speedily became an important element in the guidance of the country.

Senator John C. Breckenridge, in the July Congress of 1861, made a notable secession speech. Miss Carroll replied to this in a pamphlet containing such clear and powerful arguments that the War Department circulated a large edition, and requested her to write on other important points then being discussed with great diversity of opinion.

The following letters give some indication of the timely nature and value of the Breckenridge pamphlet:

My Dear Miss Carroll:

Your refutation of the sophistries of Senator Breckenridge's speech is full and conclusive. I trust this reply may have an extended circulation at the present time, as I am sure its perusal by the people will do much to aid the cause of the Constitution and the Union.

Caleb B. Smith.[3]

Globe Office, Aug. 8, 1861.

Dear Miss Carroll:

Allow me to thank you for the privilege of reading your admirable review of Mr. Breckenridge's speech. I have enjoyed it greatly. Especially have I been struck with its very ingenious and just exposition of the constitutional (p. 041) law bearing on the President, assailed by Mr. B., and with the very apt citation of Mr. Jefferson's opinion as to the necessity and propriety of disregarding mere legal punctilio when the source of all is in danger of destruction. The gradual development of the plot in the South to overthrow the Union is also exceedingly well depicted and with remarkable clearness. If spoken in the Senate your article would have been regarded by the country as a complete and masterly refutation of Mr. B.'s heresies. Though the peculiar position of the Globe might preclude the publication of the review, I am glad that it has not been denied to the editor of the Globe to enjoy what the Globe itself has not been privileged to contain.

I remain, with great respect, your obedient servant,

Sam'l T. Williams.[4]

September 21, 1861.

Dear Miss Carroll:

I have this moment, 11 o'clock Saturday night, finished reading your most admirable reply to the speech of Mr. Breckenridge; and now, my dear lady, I have only time to thank you for taking the trouble to embody for the use of others so much sound constitutional doctrine and so many valuable historic facts in a form so compact and manageable. The President received a copy left for him and requested me to thank you cordially for your able support.

The delay was not voluntary on my part. For some time past my time and mind have been painfully engrossed by very urgent public duties, and my best affections stirred by the present condition of Missouri, my own neglected (p. 042) and almost ruined State; and this is the reason why I have been so long deprived of the pleasure and instruction of perusing your excellent pamphlet.

I remain, with great respect and regard, your friend and

obedient servant,

Edward Bates.[5]

Appleby, Sept. 22, 1861.

My Dear Miss Carroll:

I will thank you very much if you will send me a couple of hundred copies of your reply to Breckenridge, with bill of expenses for the same. I do not think it is right that you should furnish your publications gratis any longer. I told our friends in Baltimore last week that the Union State Committee must go to work and send your documents over the entire State if they expect to carry this election. Mr. Mayer and Mr. Fickey, of the committee, said they would make application to you immediately and pay for all you can supply.

No money can ever pay for what you have done for the State and the country in this terrible crisis, but I trust and believe the time will come when all will know the debt they owe you.

With great respect, your friend and obedient servant,

Thos. H. Hicks.

Baltimore, Oct. 2, 1861.

Miss Carroll:

If you could let me have more of your last pamphlet in answer to Breckenridge, I could use them with great effect. (p. 043) I have distributed from my house on Camden street all the committee could furnish me. I set my son at the door with paper and pencil, and five hundred men called for it in one day. These are the bone and sinew of the city, wanting to know which army to enter. Please send as many as you can spare. They go like hot cakes.

Yours very respectfully,

James Tilghman.

A. S. Diven, in the House of Representatives, January 22, 1862: