The Project Gutenberg EBook of The 'Mind the Paint' Girl, by Arthur Pinero

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The 'Mind the Paint' Girl

A Comedy in Four Acts

Author: Arthur Pinero

Release Date: June 18, 2007 [EBook #21849]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE 'MIND THE PAINT' GIRL ***

Produced by Louise Hope, Branko Collin and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

This text uses utf-8 (unicode) file encoding. If the apostrophes and quotation marks in this paragraph appear as garbage, you may have an incompatible browser or unavailable fonts. First, make sure that the browser’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change your browser’s default font.

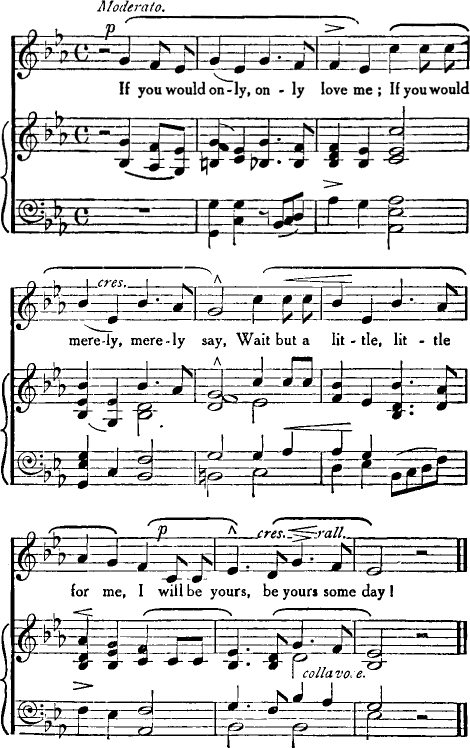

The published play did not include music for the title song ("Mind the Paint"), sung in Act I.

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They have been marked in the text with mouse-hover popups.

THE“ MIND THE PAINT ”GIRL |

First Act: Lily Parradell’s drawing room

Second Act: refreshment-saloon of Pandora Theatre

Second Act (after curtain): the same, later

Third Act:

Lily Parradell’s boudoir

Song: “If you would only love me”

Fourth Act: the same, later

| THE TIMES | |

| THE PROFLIGATE | |

THE CABINET MINISTER |

|

| THE HOBBY-HORSE | |

| LADY BOUNTIFUL | |

| THE MAGISTRATE | |

| DANDY DICK | |

| SWEET LAVENDER | |

| THE SCHOOLMISTRESS | |

THE WEAKER SEX |

|

| THE AMAZONS | |

| * | THE SECOND MRS. TANQUERAY |

THE NOTORIOUS MRS. EBBSMITH |

|

THE BENEFIT OF THE DOUBT |

|

THE PRINCESS AND THE BUTTERFLY |

|

TRELAWNY OF THE “WELLS” |

|

| † | THE GAY LORD QUEX |

| IRIS | |

| LETTY | |

| A WIFE WITHOUT A SMILE | |

HIS HOUSE IN ORDER |

|

| THE THUNDERBOLT | |

| MID-CHANNEL | |

PRESERVING MR. PANMURE |

|

THE “MIND THE PAINT” GIRL |

|

|

* This Play can be had in library form, 4to, cloth, † A Limited Edition of this play on hand-made paper, |

|

THE PINERO BIRTHDAY BOOKSelected and Arranged by MYRA

HAMILTON

|

THE“ MIND THE PAINT ”GIRL |

A COMEDYIn Four ActsBy ARTHUR PINERO |

|

|

LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN MCMXIII |

Copyright 1912

by Arthur Pinero

This play was produced in London, at the Duke of York’s Theatre, on Saturday, February 17, 1912; in New York, at the New Lyceum Theatre, on Monday, September 9, 1912; and in Germany, at the Stadttheater in Mainz, on Monday, January 13, 1913

| Viscount Farncombe | |

| Colonel the Hon. Arthur Stidulph | |

| Baron von Rettenmayer | |

| Captain Nicholas Jeyes | |

| Lionel Roper | |

| Sam de Castro | |

| Herbert Fulkerson | |

| Stewart Heneage | |

| Gerald Grimwood | |

|

Carlton Smythe (Manager of the Pandora Theatre) |

|

|

Douglas Glynn, Albert Palk, Wilfrid Tavish, and Sigismund Shirley |

(Actors at the Pandora) |

|

Vincent Bland (A Musical Composer, attached to the Pandora) |

|

|

Morris Cooling (Business Manager at the Pandora) |

|

|

Luigi (Maître d’hôtel at Catani’s Restaurant) |

|

| Waiters | |

|

The Hon. Mrs. Arthur Stidulph (Formerly, as Dolly Ensor, of the Pandora Theatre) |

|

| Lily Parradell | (Of the Pandora) |

| Jimmie Birch | |

| Gabrielle Kato | |

| Enid Moncrieff | |

| Daphne Dure | |

| Nita Trevenna | |

| Flo Connify | |

| Sybil Dermott | |

| Olga Cook | |

| Evangeline Ventris | |

|

Mrs. Upjohn (Lily Parradell’s mother) |

|

|

Gladys (Lily’s parlourmaid) |

|

|

Maud (Lily’s maid) |

|

The action of the piece takes place in London—at Lily Parradell’s house in Bloomsbury, in the foyer of the Pandora Theatre, and again at Lily’s house.

The curtain will be lowered for a few moments in the course of the Second Act.

The following advertisements are to appear conspicuously in the programme.

MIND THE PAINT (the complete song), words by D’Arcy Wingate, music by Vincent Bland, as originally sung by Miss Lily Parradell at the Pandora Theatre in the Musical Play of “The Duchess of Brixton,” may be obtained from Messrs. Church and Co. (Ltd.), Music Publishers, 181 New Bond Street.

After the Theatre. Catani’s Restaurant, 459 Strand. Best cuisine in London. Milanese Band. Private Rooms. Urbano Catani, Sole Proprietor. Tel.: 10,337 Gerrard.

The scene is a drawing-room, prettily but somewhat showily decorated. The walls are papered with a design representing large clusters of white and purple lilac. The furniture is covered with a chintz of similar pattern, and the curtains, carpet, and lamp-shades correspond.

In the wall facing the spectator are two windows, and midway between the windows there is the entrance to a conservatory. The conservatory, which is seen beyond, is of the kind that is built out over the portico of a front-door, and is plentifully stocked with flowers and hung with a velarium and green sun-blinds. In the right-hand wall there is another window and, nearer the spectator, a console-table supporting a high mirror; and in the wall on the left, opposite the console-table, there is a double-door opening into the room, the further half of which only is used.

In the entrance to the conservatory, to the right, there is a low, oblong tea-table at which are placed three small chairs; and near-by, on the left, are a 2 grand-piano and a music-stool. Against the piano there is a settee, and on the extreme left, below the door, there is an arm-chair with a little round table beside it. At the right-hand window in the wall at the back is another settee, and facing this window and settee there is a smaller arm-chair.

Not far from the fire-place there is a writing-table with a telephone-instrument upon it. A chair stands at the writing-table, its back to the window in the wall on the right; and in front of the table, opposing the settee by the piano, there is a third settee. On the left of this settee, almost in the middle of the room, is an arm-chair; and closer to the settee, on its right, are two more arm-chairs. Other articles of furniture—a cabinet, “occasional” chairs, etc., etc.—occupy spaces against the walls.

On the piano, on the console-table and cabinet, on the settee at the back, on the round table, and upon the floor, stand huge baskets of flowers, and other handsome floral devices in various forms, with cards attached to them; and lying higgledy-piggledy upon the writing-table are a heap of small packages, several little cases containing jewellery, and a litter of paper and string. The packages and the cases of jewellery are also accompanied by cards or letters.

A fierce sunlight streams down upon the velarium, and through the green blinds, in the conservatory.

[Note: Throughout, “right” and “left” are the spectators’ right and left, not the actor’s.]

Lord Farncombe, his gloves in his hand, is 3 seated in the arm-chair in the middle of the room. He is a simple-mannered, immaculately dressed young man in his early twenties, his bearing and appearance suggesting the soldier. He rises expectantly as Gladys, a flashy parlourmaid in a uniform, shows in Lionel Roper, a middle-aged individual of the type of the second-class City man.

Roper.

To Farncombe. Hul-lo! I’m in luck! Just the chap I’m hunting for. Shaking hands with Farncombe. How d’ye do, Lord Farncombe?

Farncombe.

How are you, Roper?

Gladys.

To Roper, languidly. I’ll tell Mrs. Upjohn you’re here.

Roper.

Ta. Gladys withdraws. Phew, it’s hot!

Farncombe.

Miss Parradell’s out.

Roper.

Taking off his gloves. She won’t be long, I dare say.

Farncombe.

I’ve brought her a few flowers.

4Roper.

Have you? I’ve sent her a trifle of jewellery.

Farncombe.

Glancing at the writing-table. She seems to have received a lot of jewellery.

Roper.

Bustling across to the table. By Jove, doesn’t she! Ah, there’s my brooch!

Farncombe.

Modestly. I didn’t consider I’d a right to offer her anything but flowers, on so slight an acquaintance.

Roper.

Exactly; but I’m an old friend, you know. Turning to Farncombe. Perhaps, by her next birthday——

Farncombe.

Smiling. I hope so.

Roper.

Approaching Farncombe and taking him by the lapel of his coat. What I want to say to you is, doing anything to-night?

Farncombe.

I—I shall be at the theatre.

5Roper.

Oh, we shall all be at the theatre, to shout Many Happy Returns. Later, I mean.

Farncombe.

Nothing that I can’t get out of.

Roper.

Good. Look here. Smythe is giving her a bit of supper in the foyer after the show, a dance on the stage to follow. About five-and-twenty people. ’Ull you come?

Farncombe.

If Mr. Smythe is kind enough to ask me——

Roper.

He does ask you, through me. He’s left all the arrangements to me and Morrie Cooling. Carlton never did anything in his life; I egged him on to this. I’ve been sweating at it since eleven o’clock this morning. Haven’t been near the City; not near it. Well?

Farncombe.

His eyes glowing. I shall be delighted.

Roper.

Splendid. Been trying to get on to you all day. I’ve called twice at your club and at St. James’s Place.

Farncombe.

Sorry you’ve had so much trouble.

6Roper.

Dropping on to the settee in front of the writing-table and wiping his brow. There’ll be the Baron, Sam de Castro, Bertie Fulkerson, Stew Heneage, Jerry Grimwood, Dwarf Kennedy, Colonel and Mrs. Stidulph—Dolly Ensor that was—and ourselves, besides Cooling and Vincent Bland and the pick o’ the Company. Catani does the food and drink. I don’t believe I’ve forgotten a single thing. With a change of tone, pointing to the arm-chair in the middle of the room. Sit down a minute. Farncombe sits and Roper edges nearer to him. Are you going to wait to see Lily this afternoon?

Farncombe.

I—I should like to.

Roper.

Because if Jeyes should happen to drop in while you’re here——

Farncombe.

Captain Jeyes?

Roper.

Nicko Jeyes—or if you knock up against him to-night at the theatre—mum about this.

Farncombe.

About the supper?

Roper.

Nodding. Um. We don’t want Nicko Jeyes; we simply don’t want him. And if he heard that you 7 and some of the boys are coming, he might wonder why he isn’t included.

Farncombe.

He strikes me as being rather a surly, ill-conditioned person.

Roper.

A regular loafer.

Farncombe.

He appears to live at Catani’s. I never go there without meeting him.

Roper.

Exactly. Catani’s and a top, back bedroom in Jermyn Street, and hanging about the Pandora; that’s Nicko Jeyes’s life.

Farncombe.

He’s an old friend of Mrs. Upjohn’s and Miss Parradell’s too, isn’t he?

Roper.

Evasively. Known ’em some time. That’s it; Lily’s so faithful to her old friends.

Farncombe.

Smiling. You oughtn’t to complain of that.

Roper.

Oh, but I’m a real friend. I’ve always been a patron of the musical drama—it’s my fad; and I’ve kept an eye on Lily from the moment she sprang into prominence— singing “Mind the paint! Mind the paint!” 8 —looked after her like a father. Uncle Lal she calls me. Reassuringly. I’m a married man, you know; Farncombe nods but the wife has plenty to occupy her with the kids and she leaves the drama to me. She prefers Bexhill. Leaning forward and speaking with great earnestness. Farncombe, what a charming creature!

Farncombe.

Innocently. Mrs. Roper?

Roper.

No, no, no; Lily. Hastily. Oh, and so’s my missus, for that matter, when she chooses. But Lily Upjohn——!

Farncombe.

In a low voice. Beautiful; perfectly beautiful.

Roper.

Yes, and as good as she’s beautiful; you take it from me. With a wave of the hand. Well, if you see Jeyes, you won’t——?

Farncombe.

Not a word.

Roper.

Rising and walking away to the left. I’ve warned the others. Returning to Farncombe who has also risen. By-the-bye, if Lily should mention the supper in the course of conversation, remember, she’s not in the conspiracy.

Farncombe.

Conspiracy?

9Roper.

To shunt Nicko. We’re letting her think there are to be no outsiders.

Farncombe.

Becoming slightly puzzled by Roper’s manner. Why, would she very much like Captain Jeyes to be asked?

Roper.

Rather impatiently. Haven’t I told you, once you’re a friend of Lil’s——! Looking towards the door. Is this Ma? Mrs. Upjohn enters. Hul-lo, Ma!

Mrs. Upjohn.

A podgy little, gaily dressed woman of five-and-fifty with a stupid, good-humoured face. ’Ullo, Uncle!

Roper.

Lord Farncombe——

Mrs. Upjohn.

Advancing and shaking hands with Farncombe. Glad to see you ’ere again. You ’ave been before, ’aven’t you?

Farncombe.

Last week.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Of course; you came with Mr. Bertie Fulkerson. But somebody or other’s always poppin’ in. Pleasantly. Lil sees too many, I say. It’s tirin’ for ’er. Won’t you set?

10Roper.

Lord Farncombe’s brought Lily some flowers, Ma. To Farncombe. Where are they?

Farncombe.

Who, after waiting for Mrs. Upjohn to settle herself upon the settee in front of the writing-table, sits in the chair at the end of the settee—pointing to a large basket of flowers. On the piano.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Barely glancing at the flowers. ’Ow kind of ’im! Sech a waste o’ money too! They do go off so quick.

Roper.

Reading the cards attached to the various floral gifts. Where is Lil?

Mrs. Upjohn.

She’s settin’ to a risin’ young artist in Fitzroy Street—Claude Morgan. She won’t be ’ome till past five. So tirin’ for ’er.

Roper.

Never heard of Morgan.

Mrs. Upjohn.

No, nor anybody else. That’s what I tell ’er. Why waste your time givin’ settin’s to a risin’ young artist when the big men ’ud go down on their ’ands and knees to do you? But that’s Lil all over. She’s the best-natured girl in the world, and so she gets imposed on all round.

11Farncombe.

Gallantly. I prophesy that Mr. Morgan’s picture of Miss Parradell won’t have dried before he’s quite famous.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Turning a pair of dull eyes full upon him. ’Ow do you mean?

Farncombe.

Disconcerted. Er—I mean—

Mrs. Upjohn.

Why won’t it ’ave dried?

Farncombe.

I mean he will have become celebrated before it has dried.

Mrs. Upjohn.

’Is pictures never do dry, you mean?

Roper.

No, no, Ma!

Mrs. Upjohn.

’Owever, it doesn’t matter. ’E isn’t even goin’ to put ’er name to it.

Roper.

Why not?

Mrs. Upjohn.

You may well ask. ’E’s bent on callin’ it “The ‘Mind the Paint’ Girl.”

12Roper.

What’s wrong with that? Everybody’ll recognise who that is.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Unconvinced. ’Er name’s printed on all ’er photos.

Farncombe.

The first time I had the pleasure of seeing your daughter on the stage, Mrs. Upjohn, a man next to me said, “Here comes the ‘Mind the Paint’ girl.”

Mrs. Upjohn.

Cheering up. Oh, well, p’r’aps young Morgan knows ’is own business best. Let’s ’ope so, at any rate.

Roper.

By the tea-table, beckoning to Farncombe. Farncombe——

Farncombe.

To Roper. Eh? To Mrs. Upjohn, rising. Excuse me.

Farncombe joins Roper, whereupon Mrs. Upjohn goes to the writing-table and, seating herself there, examines the jewellery delightedly.

Roper.

To Farncombe, in a whisper. Do me a favour.

Farncombe.

Certainly.

13Roper.

Looking at his watch. It’s only half-past four. Take a turn round the Square. I’ve some business to talk over with the old lady.

Farncombe.

Nodding to Roper and then coming forward and addressing Mrs. Upjohn. I—er—I think I’ll go for a little walk and come back later on, if I may.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Contentedly. Oh, jest as you like.

Farncombe.

Moving towards the door. In about a quarter-of-an-hour.

Mrs. Upjohn.

If we don’t see you again, I’ll tell Lil you’ve been ’ere.

Farncombe.

At the door. Oh, but you will; you will see me again.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Well, please yourself and you please your dearest friend, as Lil’s dad used to say.

Farncombe.

Thank you—thank you very much.

He disappears, closing the door after him.

14Mrs. Upjohn.

To Roper, looking up. I b’lieve you gave that young man the ’int to go, Uncle.

Roper.

I did; told him I wanted to talk business with you.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Business? Resuming her inspection of the trinkets. This is a ’andsome thing Mr. Grimwood’s sent ’er.

Roper.

His hands in his trouser-pockets, contemplating Mrs. Upjohn desperately. Upon my soul, Ma, you’re a champion!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Now wot ’ave I done!

Roper.

Well, you might spread yourself a little over young Farncombe.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Spread myself! Why should I?

Roper.

Lord Farncombe!

Mrs. Upjohn.

I treat ’em all alike; so does Lil. ’E’s not the first title we’ve ’ad ’ere, not by a dozen.

15Roper.

No, but damn it all—! I beg your pardon——

Mrs. Upjohn.

Beaming. So you ought—swearin’ like a trooper.

Roper.

This chap’s in love with her.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Oh, they’re all in love with ’er; or ’ave been, one time or another.

Roper.

Yes, but they’re not all Farncombes and they’re not all marrying men. I’m prepared to bet my boots that if Lil and young Farncombe could be thrown together——! Sitting on the settee in front of the writing-table as Mrs. Upjohn rises and comes forward. Here! Do talk it over.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Placidly. Where’s the use o’ talkin’ it over? It’s wastin’ one’s breath. Moving to the settee by the piano. My Lil doesn’t want to marry—any’ow not yet awhile; she’s ’appy and contented as she is. Sitting and smoothing out her skirt. When she does, I s’pose it’ll be the Captain.

Roper.

Between his teeth. The Captain! Quietly. Ma, the day Lil marries Nicko Jeyes, you and she’ll see the last o’ me.

16Mrs. Upjohn.

Oh, don’t say that, Uncle.

Roper.

I do say it. The disappointment ’ud be more than I could stand. Selfish, designing beggar!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Now, no low abuse.

Roper.

A fellow who gets on the soft side of Lil before she’s out of her teens—before she’s made any position to speak of; and when she has made a position, and he’s practically on his uppers, sticks to her like a limpet!

Mrs. Upjohn.

She sticks to ’im, too. It meant a deal to Lil in ’er ’umble days, reck’lect—receivin’ attentions from a gentleman in the army. She doesn’t forget that.

Roper.

Jumping up and walking about. It’s cruel; that’s what it is—it’s cruel. Here’s Gwennie Harker and Maidie Trevail both married to peers’ sons, and Eva Shafto to a baronet—all of ’em Pandora girls; and Lil—she’s left high and dry, engaged to a nobody! It’s cruel!

Mrs. Upjohn.

She’s not ackshally engaged.

17Roper.

Ho, ho!

Mrs. Upjohn.

The ideer was, when ’e shirked goin’ to India an’ gave up soldierin’, so as to be near ’er, that ’e should get something to do in London; then they were to be engaged.

Roper.

Sarcastically. Oh, to be just, I admit he’s in no hurry. He’s been a whole year looking for something to do in London—looking for it at Catani’s and at the Pandora bars!

Mrs. Upjohn.

’E ’as to be on the spot at night, to bring Lil ’ome after ’er work.

Roper.

Exactly! And when a decent, eligible young chap comes along, and means business, he’s choked off by finding Nicko Jeyes in possession. Stopping before Mrs. Upjohn. But, I say!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Wot?

Roper.

Farncombe hasn’t tumbled to it yet.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Indifferently. ’Asn’t ’e?

18Roper.

Bertie Fulkerson’s held his tongue about it; so have the other boys who’re friends of Farncombe’s. They see he’s hard hit. Enthusiastically. Oh, they’re good boys; they’re good, loyal boys! There’s not one of them who wouldn’t throw up his hat if Nicko got the chuck. Suddenly. Ma!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Startled. Hey?

Roper.

Dropping his voice. This little spree to-night at the theatre—Lil thinks it’s to be merely among the members of the Company.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Ain’t it?

Roper.

Sitting beside her. You keep quiet, now. No, it isn’t.

Mrs. Upjohn.

’Oo——?

Roper.

The boys—and Farncombe.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Disturbed. Gracious! There’ll be an awful fuss with the Captain to-morrer.

Roper.

Snapping his fingers. Pishhh!

19Mrs. Upjohn.

Rising and walking away to the right. ’E’s so ’orribly jealous. When Lil tells ’im ’oo was at the party, there’ll be a frightful kick-up!

Roper.

Falling into despondency. Oh, I dare say I’m a fool for my pains, Ma. Nothing’ll come of it. Rising and pacing the room again. Farncombe’s as shy as a school-girl; he’d be on a desert island with a pretty woman for a month without squeezing her hand.

Mrs. Upjohn.

In an altered tone. Uncle.

Roper.

Hullo!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Thoughtfully. I shouldn’t raise any objection, bear in mind, if Lil could be weaned away from the Captain and took a fancy to young Farncombe.

Roper.

Objection!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Sitting on the settee in front of the writing-table. All said an’ done, to be Lady F., with no need to work if you’re not disposed to, is better than bein’ Mrs. Captain Jeyes an’ ’avin’ to linger on the stage, p’r’aps, till you drop, to ’elp keep the pot a’ boilin’. Opening her eyes widely. Lady F.!

20Roper.

Coming to her. And Countess of Godalming when his father dies.

Mrs. Upjohn.

I s’pose there’d be any amount of unpleasantness with the fam’ly?

Roper.

Disdainfully. The family!

Mrs. Upjohn.

There’s generally a rumpus in sech cases.

Roper.

Why, Ma, these tiptop families ought to feel jolly grateful that we’re mixing the breed for them a bit. Look at the two lads who’ve married Gwennie Harker and Maidie Trevail—Kinterton and Glenroy; and Fawcus—Sir George Fawcus—Eva Shafto’s husband; they haven’t a chin or a forehead between ’em, and their chests are as narrow as a ten-inch plank.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Quite true.

Roper.

Farncombe himself, he’s inclined to be weedy. I maintain it’s a grand thing for our English nobs that their slips of sons have taken to marrying young women of the stamp of Maidie Trevail and Gwennie Harker—or Lil; keen-witted young women full of the joy of life, with strong frames, beautiful hair and fine eyes, and healthy pink gums and big white teeth. 21 Sneer at the Pandora girls! Great Scot, it’s my belief that the Pandora girls’ll be the salvation of the aristocracy in this country in the long run!

Captain Nicholas Jeyes lounges in. He is a man of about five-and-thirty, already slightly grey-haired, who has gone to seed. Roper sits in the chair in the middle of the room rather guiltily and Mrs. Upjohn puts on a propitiatory grin.

Jeyes.

Nodding to Mrs. Upjohn and Roper as he closes the door. Afternoon, Mrs. Upjohn. How’r’you, Roper?

Mrs. Upjohn.

Ah, Captain!

Roper.

Hullo, Nicko!

Jeyes.

Advancing. Lily not in?

Mrs. Upjohn.

No; she’s in Fitzroy Street, settin’ to Morgan.

Jeyes.

Frowning. Why didn’t she ask me to go with her?

Mrs. Upjohn.

Dun’no, I’m sure. She’s took Miss Birch.

Jeyes.

With a grunt. Oh? Looking round. Flowers.

22Mrs. Upjohn.

’Eaps of ’em, ain’t there?

Roper.

Jerking his head towards the writing-table. Yes, and some nice presents over here.

Mrs. Upjohn.

She’s beat ’er record this year, Lil ’as, out an’ out.

Jeyes goes to the writing-table and Roper and Mrs. Upjohn rise and wander away, the former to the conservatory, the latter to the settee by the piano.

Jeyes.

Scowling at the presents. Very nice. Picking up a case of jewellery. Ve-ry nice. Throwing the case down angrily. Confound ’em, what the devil do they take her for!

Roper.

At the entrance to the conservatory. I may remark that one of those gifts is from me, Jeyes.

Jeyes.

Oh, I’m not alluding to you.

Roper.

Stiffly. Much obliged.

Jeyes.

Coming forward and addressing Mrs. Upjohn. 23 I’ve called in to ask Lily whether she’ll come out to supper with me to-night, to Catani’s, to celebrate her birthday. Luigi’s decorating a table for me specially. Mr. and Mrs. Linthorne’ll come, and Jack Wethered. To Roper. Are you free, Roper? Mrs. Upjohn sits uneasily on the settee by the piano and Roper finds some object to interest him near the tea-table. I suppose it’s no good asking you, Mrs. Upjohn?

Mrs. Upjohn.

N-n-o, thank you, Captain, and I—I’m afraid——

Jeyes.

Afraid——?

Mrs. Upjohn.

I’m afraid Lil can’t manage it either.

Jeyes.

Why not?

Mrs. Upjohn.

I—I’m surprised she didn’t mention it to you ’erself when you brought ’er ’ome last night.

Jeyes.

Mention what?

Mrs. Upjohn.

They’re givin’ ’er a supper to-night at the theatre.

Jeyes.

The theatre?

Roper.

Advancing. Yes, Carlton’s standing a little spread 24 in the foyer, in honour of the occasion. Sitting at the tea-table. Quite right too; she’s his best asset, and chance it.

Jeyes.

When was it fixed up?

Roper.

Late last night.

Jeyes.

The fact is, Lily and I had a slight tiff coming home last night. Sitting on the settee in front of the writing-table. Ha! I suppose she kept it from me to pay me out. Sharply. Who’s invited?

Roper.

Er—only the principal members of the Company, I understand.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Moistening her lips with her tongue. Yes, only the members of the Company, Lil says.

Roper.

With Morrie Cooling and Vincent Bland thrown in.

Jeyes.

Looking at Roper. You seem to know a lot about it, Roper.

Roper.

I was behind when Morrie was going round to the dressing-rooms.

25Jeyes.

To Roper, suspiciously. Are you asked?

Roper.

Taken aback. E—eh?

Jeyes.

Are you asked?

Roper.

With an attempt at airiness. Oh, yes, they’ve dragged me into it.

Jeyes.

Since when have you been a member of the Company?

Roper.

No, but—dash it, I’ve done business for Carlton in the City for twenty years or more——!

Jeyes.

That doesn’t make you one.

Roper.

And I’m an old friend of Lil’s.

Jeyes.

Not older than I. Violently. Why the blazes doesn’t Smythe invite me?

Roper.

Extending his arms. My dear Nicko, I’m not 26 giving the party. Really, you do jump down a man’s throat——!

Jeyes.

Sorry, sorry, sorry. Leaning back and thrusting his hands into his pocket. Well, I’ll put Jack and the Linthornes off. They don’t want to sup with me; I shouldn’t amuse ’em. Gazing at the carpet. Her birthday, though! It’ll be the first time I shall have been out of that for—how many years?—six years. I—— Raising his head, he detects Mrs. Upjohn and Roper eyeing each other uncomfortably. Anything the matter?

Roper.

T-t-the matter?

Jeyes.

Taking his hands from his pockets and sitting upright. Any game on?

Mrs. Upjohn.

Game?

Jeyes.

At my expense?

Mrs. Upjohn.

I dun’no wot you’re drivin’ at, Captain.

Jeyes.

Harshly. How long’s Lily sitting this afternoon?

Mrs. Upjohn.

Till five.

27Jeyes.

Looking at his watch. What’s Morgan’s number in Fitzroy Street?

Mrs. Upjohn.

Sixty.

Jeyes.

Rising. I’ll fetch her.

As he makes a movement towards the door, it is thrown open and Lily Parradell enters with a rush—an entrancing vision of youth, grace, and beauty. She is followed by Jimmie Birch, a petite, bright-eyed girl in an extremely chic costume.

Lily.

Tearing off her gloves as she enters. Wh-e-e-w! I’m dead! Giving her hand to Jeyes carelessly. Ah, Nicko! To Mrs. Upjohn. I couldn’t stand the heat in the studio any longer, mother. Finding Roper beside her, she offers her cheek to him and he kisses it. Mon Oncle!

Jimmie.

Closing the door. That young man Morgan ought to paint the infernal regions.

Lily.

Taking her scarf from her shoulder. He might finish with the angels first, though. To Jeyes, softly, as Roper turns to shake hands with Jimmie. You in a better temper to-day?

28Jeyes.

In her ear. You drove me wild last night.

Lily.

Making a face at him. Served you right. Passing him. For God’s sake, let me lie down. She throws herself upon the settee in front of the writing-table, and Jeyes moves away as Mrs. Upjohn and Roper go to her. Don’t come near me. Give me my fan. Jimmie, where’s my fan?

Jimmie.

Oh, I’ve left it in Fitzroy Street!

Lily.

Beast!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Hurrying to the writing-table. There’s one ’ere, among your presents.

Lily.

Unpinning her hat. Uncle Lal, what an adorable ring that is you’ve sent me!

Roper.

Taking the fan from Mrs. Upjohn. Ring! A brooch!

Lily.

Somebody’s sent me a ring.

29Mrs. Upjohn.

Sitting in the chair at the end of the settee by the writing-table. There’s three rings.

Lily.

Of course! One of them’s from Nicko! To Jeyes. Did you get my sweet telegram, Nicko?

Jeyes.

Who has greeted Jimmie and is now seated in the chair on the extreme left—sulkily. I had your telegram, but it’s a pendant I sent you.

Jimmie.

Sitting upon the settee by the piano and pulling off her gloves. Ha, ha, ha!

Lily.

You shut up, Jimmie. Snatching the fan from Roper. How on earth am I to remember! Fanning herself. Who’s given me this pretty thing?

Mrs. Upjohn.

Mr. Monty Levine.

Lily.

Bless him! He’s a dear little man, though he does bite his nails. Gladys appears with Vincent Bland, who saunters in after her. Seeing Lily, Gladys advances to her. Hallo, Vincent!

Bland.

A thin, delicate looking man of eight-and-thirty, not 30 over smartly dressed, wearing an eye-glass—nodding to Lily casually. You needn’t have cut me, almost on your door-step. To Jimmie and Jeyes. H’lo, Jimmie! H’lo, Nicko!

Gladys.

Viewing Lily with an elevation of the brows. Oh, are you home?

Lily.

Returning Gladys’s stare. Apparently.

Gladys.

I’ll whistle up to Maud.

Lily.

Don’t, if it’s too severe a strain on you.

Mrs. Upjohn.

To Gladys, as the girl moves to the door. Gladys, we’ll ’ave tea.

Gladys.

At the door. You can’t till it’s ready.

Lily.

Calmly. Cheek!

Gladys retires.

Bland.

Who has strolled across to Lily, indolently. Why do you retain the services of that tousled-headed hussy?

31Lily.

With conviction. Oh, she’s a little under the weather, but she’s a perfect servant.

Bland.

To Mrs. Upjohn. Ma, you look blooming.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Wish I could return the compliment, Mr. Bland.

Bland.

To Roper, who is wearing a waistcoat of rather a pronounced pattern. Congratulations on your waistcoat, Lal.

Roper.

Joining Jimmie, annoyed. Now, no personalities.

Lily.

Giving Bland her hand. Vincent, yours is one of the loveliest presents I’ve had to-day. Remerciement! How’s that for a French accent?

Bland.

Dropping his eyeglass. You cat!

Lily.

Why——?

Bland.

You know I’ve given you nothing, not even a penny nosegay.

32Jimmie.

Ha, ha, ha!

Lily.

Raising herself on her elbow. On my honour—! Vincent dear, I swear I thought——!

Bland.

The funds are too low. Replacing his eyeglass. I did go so far as to price a bangle at Sellby’s, but that was before a certain event yesterday.

Jimmie.

What horses did you back, Vincent? I won a fiver, through Jerry Grimwood.

Roper.

To Bland. You are a patent ass. Why don’t you leave betting alone?

Bland.

To Roper, flaring up. Why don’t you leave your City muck alone?

Lily.

Putting her feet to the floor, imperiously. That’ll do. Be quiet, you two! I won’t have any wrangling in my house. Run away and play, all of you. I want to speak to Vincent for a minute privately. With a gesture. Uncle Lal—Jimmie—Nicko— To Mrs. Upjohn. Scoot, mother!

33Mrs. Upjohn.

Oh, dear, wot a child!

Roper, Jimmie, Jeyes, and Mrs. Upjohn move away and Lily beckons to Bland.

Lily.

Vin.

Bland.

Close to her, with a wry face. Mercy!

Lily.

In a low voice. You’ve broken your word to me, then? Through her teeth. Those damned horses!

Bland.

Cooling had a tip from the stable——

Lily.

Cooling! Morrie Cooling has no children; only a fat wife. You’ve a darling little wife and three kiddies. How much did you drop yesterday?

Bland.

Shan’t say.

Lily.

Rising and touching his arm. Oh, Vincent!

She looks round, to assure herself that she is unobserved. Mrs. Upjohn and Roper are seated at the tea-table with their heads together, talking; Jimmie is at the piano, fingering out a piece of music; Jeyes is half hidden in the arm-chair facing the 34 settee at the back. Lily tiptoes to the writing-table and seats herself there as Gladys reappears showing in the Baron von Rettenmayer.

Von Rettenmayer.

A tall, fair young man of three-and-thirty, speaking in thick, guttural tones—advancing to Lily. Aha, goddess! Gladys withdraws. Many habby returns of the day!

Lily.

H’sh! I’m busy for a moment, Baron.

Von Rettenmayer.

To Lily—shaking hands with Bland. A thousand bardons.

Lily.

Talk to mother and Jimmie.

Von Rettenmayer.

With bleasure. Going to Mrs. Upjohn and Roper and shaking hands with them. How are you, my dear Ma? How are you, Jimmie? Waving a hand to Roper and Jeyes. My dear Rober! My dear Neegolas!

Jimmie.

To Von Rettenmayer, mimicking him. Rober! Neegolas! Why don’t they provide you with throat lozenges at the Embassy, Baron?

Von Rettenmayer laughs. Lily has quickly opened a drawer in the writing-table and produced a cheque-book. After another 35 glance over her shoulder, she sweeps the presents aside and writes. Then she replaces the cheque-book, rises, and returns to Bland. Again there is a loud guffaw from Von Rettenmayer in response to some sally of Jimmie’s.

Lily.

To Bland, folding a cheque and slipping it into his hand. Promise—promise you won’t make another bet.

Bland.

Unfolding the cheque. Your cheque?

Lily.

Hastily. Put it in your pocket.

Bland.

A blank one.

Lily.

In a whisper. Don’t fill it in for more than you can help. I’m not over flush.

He deliberately tears the cheque into four pieces and, looking at her steadily, puts them into his waistcoat-pocket.

Bland.

As he does so. I’ll keep those, Lil, for as long as I keep anything.

Lily.

Hotly. You fool, Vincent!

36Bland.

My dear, as if——!

Lily.

Such ridiculous pride! Stamping her foot. Lord, what I owe to you!

Gladys enters with Sam de Castro. Gladys is carrying a lace-edged table-cloth which, assisted by Mrs. Upjohn, she proceeds to lay upon the tea-table.

Bland.

Moving away to join the others—to De Castro. Ha, Sam!

De Castro.

A stout, coarse, but genial-looking gentleman of forty, of marked Jewish appearance, speaking with a lisp—shaking hands with Lily. How are you to-day, Lil? Many happy returnth, wunth more.

Lily.

Thanks, dear old boy. Sitting on the settee in front of the writing-table. Did I send you a wire this morning?

De Castro.

Not you; not a thix-pen’north.

Lily.

I ought to have done so, to acknowledge your—what was it?

De Castro.

A ring—diamondth and thapphires.

37Lily.

Ah, yes; beautiful.

De Castro.

It ith rather a nithe ring. Lowering his voice. But I thay.

Lily.

What?

De Castro.

Mind you don’t go and tell Gabth, on any account.

Lily.

With a great assumption of ignorance, raising her eyebrows. Gabs?

De Castro.

Gabrielle—Mith Kato.

Lily.

Why shouldn’t I?

De Castro.

Nonsenth; you know very well. Urgently. You won’t, will you?

Lily.

Shrugging her shoulders. I won’t if I remember not to.

De Castro.

Alarmed. Ah, now, don’t be thtupid! Whath the good o’ making mithchief! Lily shows him the tip of her tongue. Oh, Lil! Gladys goes out. Lil——!

38Von Rettenmayer.

Leaving the group at the back and putting an arm round De Castro’s shoulder. My dear friend Zam!

De Castro.

How are you, Baron? Going to Mrs. Upjohn. Afthernoon, Ma! Nodding to Jimmie and Roper. Afthernoon, everybody! Shaking hands with Jeyes, who has risen and now joins the group. How are you, Nicko?

Lily.

Giving her hand to Von Rettenmayer. Excuse me for cutting you short when you came in. Thanks for your splendid present. I did send you a wire, didn’t I?

Von Rettenmayer.

Kissing her hand and bowing over it. I shall breserve it, with a few oder souvenirs, till the end of my life.

Lily.

Withdrawing her hand and blowing the compliment away. Phew! Lal, lal, lal, la!

Von Rettenmayer.

In an altered tone, after a cautious look round. Goddess.

Lily.

Eh?

39Von Rettenmayer.

Anxiously. My drifling liddle offering—I endreat you not to mention it to Enid.

Lily.

Laughing heartily. Ha, ha, ha, ha! Another of you!

Von Rettenmayer.

The gharming Miss Mongreiff.

Lily.

Seriously. Baron, I wish you boys wouldn’t make me presents and then ask me to keep them a secret from the other girls.

Von Rettenmayer.

And I—I wish it were not nezezzary. But, goddess, you are alzo a young lady of the world—you know what women are.

Lily.

H’m! I know what you men are.

Maud, a buxom young woman with a good-tempered face, dressed as a lady’s-maid, enters quickly, tying her apron, and runs to Lily. Jeyes comes to the further side of the writing-table and Von Rettenmayer now joins him there. Jimmie Birch also comes forward, accompanied by De Castro.

Maud.

To Lily. Here, give me your things. Lily tosses 40 her hat, scarf, and gloves to Maud. I was in my room, having a lie down. Is my hair untidy?

Lily.

I’ve never seen it anything else.

Maud.

Merrily. Ha, ha, ha! To Jimmie and De Castro. Afternoon, Miss Jimmie. Afternoon, Mr. de Castro. To Lily. Now, don’t let them all tire you to death, there’s a pet.

Lily.

Oh, clear out. As Maud is departing. Hi! Rising and kicking off her shoes and sending them in Maud’s direction. Fetch me a pair of slippers.

Maud.

Picking up the shoes and chuckling. He, he, he!

When Maud reaches the door, which she has left open, Gladys appears with the tea-tray and with Farncombe at her heels.

Gladys.

To Maud, in a low voice, witheringly. Oh, you’re doing something, are you?

Maud.

In the same tone, passing Gladys. Yes, setting you an example, my girl. Encountering Farncombe. Beg pardon.

Maud withdraws, closing the door, and Farncombe stands looking at Lily, who is talking 41 to Jimmie. Gladys carries the tray to the tea-table.

Lily.

Become aware of Farncombe’s presence and nodding to him. How d’ye do?

Farncombe.

Moving a step or two towards her. I—I’ve been here before this afternoon. I ventured to bring you some flowers.

Lily.

Going to him and shaking hands with him formally. Nobody told me. Awfully kind of you. Where have they put them?

Farncombe.

Lifting his basket of flowers from off the piano and showing it to her. Here.

Lily.

Pretty. Pulling out a carnation. Stick it up there again. He replaces the basket. You’re Lord Farncombe, aren’t you?

Farncombe.

Yes.

Lily.

With a glance at the others. Know anybody here?

Farncombe.

Looking round the room. Nearly everybody, I fancy. He advances to Von Rettenmayer, who comes 42 to meet him. Lily sits upon the settee by the piano and fastens the carnation in her dress. Gladys goes out. Karl——!

Von Rettenmayer.

My dear Eddie!

Farncombe.

Bowing to de Castro, who is now seated beside Jimmie on the settee in front of the writing-table. How are you, Mr. de Castro? To Jeyes, who is standing by the chair at the writing-table gnawing his moustache and watching Lily and Farncombe sourly. How are you, Captain Jeyes? Turning to Bland. How are you, Mr. Bland? To Lily. I’ve been talking to Mrs. Upjohn and Mr. Roper already.

Lily.

Looking across to Jimmie. Miss Birch—Lord Farncombe.

Jimmie.

Nodding to Farncombe. How d’ye do?

Farncombe.

Going to Jimmie and shaking hands with her. I—I needn’t say that I am one of Miss Birch’s warmest—most profound——

Jimmie.

Smiling at him. That’s all right; don’t you bother about that.

Maud returns, carrying a pair of silken slippers. Von Rettenmayer, who has come to Lily, 43 makes a dart at the slippers and takes them from Maud.

Von Rettenmayer.

Aha! Permid me.

Maud.

Now, Baron——! Slapping his arm. Ha, ha, ha——!

He pushes Maud out of the room, she resisting laughingly, and closes the door.

Von Rettenmayer.

Holding the slippers aloft. Gendlemen! Homage to Beaudy! Vollow me! Zam! Vinzent! Rober! Neego! Eddie! The men put themselves behind him, in single file, in the order in which he calls them, with the exception of Jeyes, who deliberately sits at the writing-table, and Farncombe, who is embarrassed. Jimmie claps her hands and Mrs. Upjohn, who is pouring out tea, laughs herself into a fit of coughing. Ta, ta, ra, ra, ta, ta! Boum, boum!

Lily.

Baron, you great baby!

Von Rettenmayer.

Quig! Marge!

Roper.

Calling to Farncombe. Come along, Farncombe!

Jimmie.

Giving Farncombe a shove. Go on!

44Farncombe takes his place behind Roper and, headed by Von Rettenmayer, the men march round the room.

Von Rettenmayer.

Waving the slippers in the air and singing.

Weib, was ist in aller Welt

Dir an Schönheit gleichgestellt!

Reizumflossen, wunderhold,

Perl’ der Schöpfung, Herzensgold!

Tag’s Gedanken, Traum der Nacht,

Schweben um Dich, Süsse, sacht.

Von Rettenmayer halts before Lily and kneels to her. She extends her left foot and he kisses her instep and puts her foot into her slipper. She rewards him by lightly boxing his ears. He makes way for de Castro, handing him the other slipper, and de Castro performs the same ceremony with Lily’s right foot. She upsets de Castro’s balance by a little kick.

Von Rettenmayer.

Seating himself beside Jimmie, singing.

Venus, seinen Nacken beut

Dir Den Sklave, dienstbereit!

De Castro gathers himself up and sits in the chair at the end of the settee in front of the, writing-table. Bland and Roper, having knelt and kissed Lily’s foot, also sit, the former in the chair in the middle of the room, the latter in the chair on the extreme left. Finally, Farncombe finds himself 45 before Lily. He looks at her hesitatingly and she returns his look with awakened interest and withdraws her foot.

Lily.

Shaking her head. No, no; don’t you be silly, like the others.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Loudly. Tea!

Bland, Von Rettenmayer and de Castro jump up and go to the tea-table where Farncombe joins them. Gladys enters, carrying a stand on which are a plate of bread-and-butter, a dish of cake, etc. Roper takes the stand from her and the girl retires. Farncombe brings Lily a cup of tea. De Castro and Bland follow him, the one with a milk-jug, the other with a sugar-basin. Von Rettenmayer carries a cup of tea to Jimmie, and then de Castro and Bland, having waited upon Lily, go to Jimmie with the milk and sugar. Roper hands the bread-and-butter and cake to Lily, then to Jimmie, and in the end Roper, Bland, de Castro and Von Rettenmayer assemble at the tea-table and receive their cups of tea from Mrs. Upjohn.

Roper.

Relieving Gladys of the stand. Give it to me. I want a little exercise.

46Lily.

Taking her cup of tea from Farncombe. Thanks.

De Castro.

Helping Lily to milk. Milk-ho!

Bland.

Sugar?

Lily.

Br-r-r-rh! I’m putting on weight as it is.

Roper.

Offering the bread-and-butter, etc.—facetiously. Ices, sweets or chocolates, full piano-score!

Lily.

Nothing to eat, Uncle; I dine at six.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Calling to Jeyes from the tea-table. Captain, ain’t you goin’ to ’ave any tea?

Jeyes.

Moodily examining the presents on the writing-table. No, thank you, Mrs. Upjohn.

Bland.

To Jimmie, after she has been helped to milk. Sugar?

Jimmie.

Two lumps.

47Roper.

Pushing Bland and de Castro aside, imitating a female voice. Ices, sweets or chocolates, full piano-score!

Jimmie.

Cutting a slice of cake. Lal, the world ’ud be a much happier place to live in if Lloyd George taxed your jokes.

Von Rettenmayer, Bland, and de Castro.

Returning to the tea-table. Ha, ha, ha, ha!

Lily.

To Farncombe, who remains standing near her. Seen our show at the Pandora?

Farncombe.

Gazing at her. Twenty-three times.

Lily.

Not really?

Farncombe.

This week and last, every night.

Lily.

Running her eye over him. You in the Guards, by any chance?

Farncombe.

Nodding. Yes.

48Lily.

Smiling. Ah, you’ll never do a braver deed than seeing our show twenty-three times.

Jimmie.

As Roper leaves her to go to the table, her mouth full of cake. Boys! Choking. Heugh, heugh, heugh! Wait a minute; I’ve swallowed some of the Baron’s German. Gulping. B-oys, seriously—no rot— raising her tea-cup jolly good health to Lily! There is a cry of approbation from Bland, Von Rettenmayer, de Castro and Roper. Farncombe fetches himself a cup of tea from the tea-table. She’s a white woman, Lily is—the staunchest, truest pal, where she takes a liking——

Bland, Von Rettenmayer, de Castro, and Roper.

Hear, hear!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Pressing forward through the men and going to Lily. And the best daughter breathing. Embracing Lily and then turning to the others. D’ye notice the new dress I’m wearin’ this afternoon?

Lily.

Don’t, mother; don’t.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Fifteen guineas it’s cost her. Sitting in the chair on the extreme left, proudly. Madame Godolphin made it, and a ’at to go with it ong sweet.

49Lily.

To Mrs. Upjohn. Hu-s-s-sh!

Jimmie.

Well—— sipping her tea as if drinking a toast in a cup of tea!

Bland, de Castro, and Roper.

Sipping their tea. In a cup o’ tea!

Von Rettenmayer.

Drinking. In a gob o’ dea!

Jimmie.

To Von Rettenmayer, mockingly. Gob o’ dea!

Lily.

Waving her hand. Thank you, Jimmie. Thank you, dear boys, from the bottom of my heart.

Jimmie.

To the men. By Jove, she saved me once from going home to a cheap lodging and taking a dose of rat-killer!

Von Rettenmayer.

Behind Roper and de Castro, peeping over their shoulders. A pidy—a gread pidy.

Jimmie.

To Von Rettenmayer. I’ll attend to you presently, Baron.

50Lily.

To Jimmie. I remember. A wretched little shrimp you looked that day.

Jimmie.

To everybody. It was my first morning at the Pandora. They’d had me up from Harrogate in a hurry, to take Gwennie Harker’s place. I’d been playing her part in the Number Two Co. in the country; and she’d left ’em in a hole, to get married to a stupid lord—— To Farncombe, finding him standing near her. Sorry. I was to have only one rehearsal; clenching her fist and, oh, didn’t they treat me abominably! Miss Ensor was late and we were all hanging about on the stage, waiting for her. I’ve never felt so cold in my life, or so lonely. Not a word of welcome, not a nod, from a single soul; simply a blank stare occasionally from a haughty beauty with a curled lip! And at last, when I was on the point of howling, I became conscious that somebody was watching me—a tall, pretty thing in a lavender frock——

De Castro.

Sitting in the chair in the middle of the room. Lil.

Jimmie.

I caught her eye, and she came straight over to me and sat down beside me. “Shaky?” she said. “A corpse,” I said. And she quietly laid hold of my hand and held it till Dolly Ensor condescended to stroll in. And when I got up I asked her who she was, and she told me. “Oh, my God,” I said, “I’ll 51 never forget your kindness! Why, of course, you’re the ‘Mind the Paint’ girl——!”

Roper, de Castro, and Von Rettenmayer.

Singing. “Mind the paint! Mind the paint! Tra, lal, la, lal, la, lal, la, lal, la, lal, tra, la, la, la——!”

Bland seats himself at the piano and thumps out the air of the refrain of “Mind the Paint.” The three men, mouthing the time silently, wave their arms, and Lily’s head and body move from side to side.

Bland.

With a groan. Ugh! Is there anything more ancient than a four-year-old comic song? Playing a few bars of the melody of the song. Shade of Nineveh and all the buried cities!

Roper, Von Rettenmayer, and de Castro.

To Lily, coaxingly. Lily! Goddess! Lil!

Lily.

Shaking her head. Oh, boys, it’s gone. Pressing temples. I couldn’t——

Bland plays the introductory symphony and then pauses. Then she sings, he accompanying her. In a moment or two, the song comes back to her readily and she gives it with great witchery and allurement. Jeyes starts up and goes to the window in the wall on the right and looks out.

52Lily.

Singing.

I’ve a very charming dwelling,

(You know where without the telling)

Decorated in a style that’s rather quaint!

Smart and quaint!

When you pay my house a visit,

You may scrutinise or quiz it,

But you mustn’t touch the paint!

Brand-new paint!

Mind the paint! Mind the paint!

(No matter whether Maple’s bills are settled or they ain’t!)

Once you smear it or you scratch it,

It’s impossible to match it;

So take care, please, of the paint—of the paint!

Rising and coming to the middle of the room, Lily repeats the refrain, dancing to it gracefully. Jimmie also rises and she, Roper, Von Rettenmayer, and de Castro join in the chorus and the dance, the three men very extravagantly. Farncombe looks on, enraptured, while Mrs. Upjohn beats time with her hands.

Lily.

Singing.

I’m possessed of all the graces,

Oh, a perfect dr-r-r-ream my face is!

(It may owe to Art a trifle or it mayn’t

H’m, it mayn’t!)

And I’ll cry out for assistance.

Should you fail to keep your distance,

53 Goodness gracious, mind the paint!

Mind the paint!

Mind the paint! Mind the paint!

A girl is not a sinner just because she’s not a saint!

But my heart shall hold you dearer—

You may come a little nearer—

If you’ll only mind the paint—mind the paint!

The refrain is repeated as before, Mrs. Upjohn rising and taking a share in it. Then Lily drops on to the settee before the writing-table, laughing and holding up her hands in protest.

Lily.

No more, boys! Roper, Von Rettenmayer, and de Castro gather round her, applauding her and urging her to continue. No, no; no more! I’ve had such a stiff day——

Mrs. Upjohn.

With sudden energy, to everybody. Out you go, all of you; out you go!

Jimmie.

To the men. Come on; let’s mizzle. Shaking hands with Farncombe. Cruel of us to tire her so.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Tapping Von Rettenmayer on the shoulder. Now, then, Baron!

Von Rettenmayer.

Shaking hands with Lily. I’m goming.

54Jimmie.

Taking Von Rettenmayer to the door. Well, gome!

Mrs. Upjohn.

Pulling Roper away from Lily. Now, Uncle!

Roper.

Adjusting his coat. Mind the paint, Ma.

Jimmie.

Calling out. Good-bye, Lil!

Lily.

As she shakes hands with de Castro, calling to Jimmie. Good-bye!

Jimmie and Von Rettenmayer disappear.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Now, Mr. de Castro! Moving with Roper towards the door. ’Owever d’ye think she’s goin’ to get through her work to-night!

De Castro.

Pausing to comb his moustache. Quite right, Ma—— thoughtlessly and a thupper and a danthe afterwardth.

Roper.

Turning upon him quickly. Sssh! In a low voice. Dam fool!

55De Castro.

Clapping his hand to his mouth. Oh——!

They glance at Jeyes who, hearing de Castro’s remark, has left the window and come forward a step or two.

Roper.

Uneasily. Er—good-bye, Nicko.

De Castro.

To Jeyes, in the same way. G-good-bye.

Jeyes.

To both, dryly. Good-bye.

Bland.

Talking to Lily, neither of them having heard de Castro’s slip. That jingle—an echo of old times, eh?

Lily.

Looking up at him. Yes, but not better times than these times, Vin?

Bland.

Sadly, holding her hand. Ah, Lil, there are so many tunes in life left for you, my dear!

Roper.

At the door, with Mrs. Upjohn and de Castro—to Bland. Come along, Vincent.

Bland joins the group at the door as Farncombe approaches Lily.

56Farncombe.

Shaking hands with her. Thank you. With fervour. Glorious!

Lily.

Reproachfully. For shame!

Farncombe.

I mean it.

Lily.

T’sh! Lightly. See you again some day, perhaps?

Farncombe.

Ah, yes—

Roper.

Calling to Farncombe. Coming our way, Farncombe?

Roper, Bland, and de Castro depart. Farncombe bows to Lily and makes for the door.

Farncombe.

To Jeyes. Good-bye, Captain Jeyes.

Jeyes.

Who has wandered to the entrance to the conservatory, where he is now standing with his back to the room—half turning. Good-bye.

Farncombe.

Shaking hands with Mrs. Upjohn. Delightful! Enjoyed myself amazingly.

57Mrs. Upjohn.

Graciously. Oh, we’re always glad when a few folks pop in— he wrings her hand if they don’t over-stay their welcome.

Farncombe.

Naturally. Hurriedly. Good-bye. He vanishes.

Mrs. Upjohn.

Remaining at the door. Captain——

Jeyes.

Advancing. I want just half a dozen words with Lily, Mrs. Upjohn.

Lily.

To Mrs. Upjohn. Tell Maud to put out my old green frock, mother; I’ll be up in a minute or two.

Mrs. Upjohn.

To Jeyes. Now, you won’t keep ’er longer, will you?

Jeyes.

Grimly. No, no; I know she won’t be in bed till four o’clock to-morrow morning at the earliest. Mrs. Upjohn goes out, closing the door, and Jeyes comes to Lily. So Smythe is giving you a grand feed to-night at the theatre, Lil?

Lily.

Arranging the pillows on the settee. In the foyer.

58Jeyes.

And a dance, it appears.

Lily.

Yawning. Oh-h-h-h! Lying upon the settee at full length. Who told you, grumpy?

Jeyes.

Roper and your mother told me about the supper. You didn’t.

Lily.

Ha, ha! You were in such a vile mood last night, coming home.

Jeyes.

Who will there be to dance with to-night?

Lily.

The men of the Company.

Jeyes.

That doesn’t sound very inspiring.

Lily.

Rather school-treaty, isn’t it!

Jeyes.

Nobody from outside?

Lily.

No; it’s to be only the men in the theatre and the principal ladies.

59Jeyes.

Roper’s going.

Lily.

Uncle Lal? Oh, well, he’s hardly from outside.

Jeyes.

And de Castro.

Lily.

Sam?

Jeyes.

I’m sure of it, from something I heard him say just now.

Lily.

Sam used to finance Carlton. I suppose they reckon him one of us.

Jeyes.

Sitting in the chair in the middle of the room. Smythe might have extended the compliment to me, Lil. He knows how I stand towards you.

Lily.

Awfully sorry; I can’t help it.

Jeyes.

Twining his fingers together. You see, if Roper and de Castro are asked, there may be others.

Lily.

Changing her position. Oh, lal, lal, lal, lal, la!

60Jeyes.

With a set jaw. Some of the more juvenile “boys,” perhaps. Examining his nails. Lil.

Lily.

What?

Jeyes.

When did you make the acquaintance of the young sprig o’ the nobility who’s been here this afternoon?

Lily.

Lord Farncombe? Bertie brought him and introduced him one day last week.

Jeyes.

Ha! He’s at your feet now.

Lily.

Phuh!

Jeyes.

Oh, you may “phuh”! He’s in front every blessed night. There he sits, Row B., three stalls from the end, prompt side!

Lily.

There are a few good-looking girls at the Pandora besides your humble servant.

Jeyes.

Rubbish! His glass follows you all over the stage. I watched him talking to you in this room——

61Lily.

Raising herself. Did you indeed!

Jeyes.

Beating his clenched hands upon the arms of his chair. God in heaven! First it’s one, then it’s another, chasing you!

Lily.

Putting her feet to the ground. Oh, you’re maddening, Nicko! You are; you’re maddening. Last night it was Stewie Heneage you chose to be jealous of, simply because you’d heard him sounding my praises at Catani’s! You almost broke the window of the car, you went on so!

Jeyes.

I confess I object to Heneage, or any man, raving about you at the top of his voice in a public place.

Lily.

Sakes alive, why shouldn’t Stewie rave about me in a public place, if he feels like it! I belong to the public. He might rave about a girl who’s a jolly sight less deserving of being raved about, as a girl and an artist, than I am.

Jeyes.

Well, we’ll dismiss Heneage.

Lily.

Yes, exit Stewie and enter somebody else for you fuss and fume about. This afternoon it’s Lord 62 Farncombe, and to-morrow it’ll be a fresh person altogether. One ’ud think, to hear you, that I don’t know how to take care of myself, and of any poor boy who loses his head over me! Rising and walking away. You’re growing worse and worse with your jealousy, Nicko. Stop it! I’m surprised at you, after all these years! It’s beginning to fret me, and that’s bad for my spirits and bad for me in business. At the tea-table, grabbing a piece of bread-and-butter and biting at it. And now you’re making me spoil my dinner— relenting and that’s not good for me either, you brute!

Jeyes.

His hands hanging loosely between his knees, sighing heavily. Oh, Lily, Lily——!

Lily.

Yes, oh, Lily, Lily!

Jeyes.

Why—why don’t you put me out of my misery?

Lily.

Munching. Poison you?

Jeyes.

Marry me.

Lily.

Behind his chair. Marry you? Taking his handkerchief from his breast-pocket and wiping her fingers upon it—sarcastically. Have you come to tell me you’ve got some work to do at last? Break it gently, Nicko; the shock might be too great for me.

63Jeyes.

Oh, I’d find a billet soon enough, Lil, if only I’d an incentive to hunt for it.

Lily.

Incentive! You had an incentive twelve months ago, when I was willing to engage myself to you absolutely if you could obtain a good secretaryship or something of the sort.

Jeyes.

I—I’ve no fancy for a beggarly secretaryship.

Lily.

No; all you’ve a fancy for, seemingly, is for living on your unfortunate people. Throwing him his handkerchief and leaving him. How a man of your age can rest satisfied with being a burden to others passes my dull comprehension!

Jeyes.

I—I have been a bit slack, I own—I have been a bit leisurely; but——

Lily.

Inspecting some of the flowers about the room. Nicko, that pendant, or whatever it is, you’ve given me—I don’t want to hurt you, but I won’t accept it. You take it away with you; do you hear?

Jeyes.

Not heeding her, weakly. Lil——

64Lily.

I’m in earnest; you remove it from off my premises.

Jeyes.

Lil— she returns to him my eldest brother—Robert— looking up at her Bob— She nods inquiringly. Bob’s at me to go out to Rhodesia, to manage a group of stock farms he’s interested in near Bulawayo.

Lily.

Oh, why don’t you go?

Jeyes.

Forlornly. Rhodesia! Bulawayo! Looking up at her again with a dismal smile. Come with me?

Lily.

Don’t be absurd.

Jeyes.

Rising and putting his hands upon her shoulders. No, you wouldn’t care a straw—not a brass farthing—if I did go, would yer!

Lily.

Softening again. Stuff! I should miss you horribly. Toying with a button of his waistcoat. Who’d bring me home from the theatre at night then, and from rehearsals; who——?

Jeyes.

Ah, who! His grip tightening on her. Who!

65Lily.

Wincing. Ssss! You’ll bruise my skin if you’re not careful.

Jeyes.

Taking her hand and crumpling it in his. Well, it might be that you’d miss me for a while—the old dog that you’re accustomed to find lying on your door-mat; pressing her hand to his lips but you don’t love me, Lil—not even as much as you did a year ago. You don’t love me!

Lily.

With a faint shrug of her shoulders. Perhaps I don’t, in the way you mean; wistfully perhaps it’s not in me really to love anybody in a marrying way. Meeting his eyes. Still, as you say——

Jeyes.

As I say——?

Lily.

Pursing her mouth at him winningly. I’m accustomed to you, Nicko. He draws her to him; but, with a laugh, she checks him by offering him her head to kiss. There— putting the point of her finger playfully on the crown of her head you may there. As he kisses her. Now I must run upstairs, or mother’ll whack me.

Jeyes.

Detaining her. Won’t you allow me to fetch you after the dance?

Lily.

Three or four in the morning! No; I’ll give you 66 a rest. Uncle Lal or Sam’ll take on your job. Going to the door. And don’t try to see me to-morrow.

Jeyes.

Sharply. Why not?

Lily.

Not till you turn up at night as usual. I shall be a shocking rag all day.

Jeyes.

Breaking out. Yes, I expect you’ll manage to enjoy yourself thoroughly, and dance yourself off your feet, whoever your partners may be!

Lily.

Wilfully. Expect I shall. Tossing her head up. Ha, ha! I’ll do my best.

She departs, leaving him standing near the tea-table. He takes out his handkerchief and mops his brow. As he does so, his eyes rest upon the telephone-instrument on the writing-table and he stares at it. He hesitates, as if struggling to resist an impulse; then he goes quickly to the instrument and puts the receiver to his ear.

Jeyes.

After a pause. Gerrard, three, eight, four, eight. Discovering that Lily has left the door wide open, he lays the receiver upon the writing-table and goes to the door and shuts it. Then he returns to the writing-table and again listens at the receiver. Is that the office of the Pandora Theatre?... Suddenly, imitating the 67 voice of de Castro. Ith Mithter Morrith Cooling in?... I’m Mithter de Castro ... Tham de Castro ... Gone, ith he?... Oh, ith that you, Mithter Hickthon?... Yeth, you’ll do ... About the thupper-party to-night that Mithter Smythe ith giving to Mith Parradell ... Yer there?... I didn’t quite underthtand whether ith to be at the theatre or at a rethtaurong ... At the theatre?... Oh, yeth ... A largth party?... Oh, that ith nithe!... Who are the guesth, d’ye know?... Yeth?... Yeth?... Oh, an’ the boyth!... oh, thome o’ the boyth are comin’, are they!... Hey?... Haven’t got the litht from Mithter Roper yet?... Oh, he’th been helpin’ to get it up!... Oh, we shall have a thplendid time!... The boyth!... Yeth!... Yeth!... ha, ha, ha, ha!... thankth.... goo’bye!

He replaces the receiver and stands looking at the door for a moment. Then, with his head bent and his hands clasped behind him, he goes slowly out.

The scene is an artistically decorated refreshment-saloon—or “foyer”—on the first-circle floor of a theatre. The wall facing the spectator is panelled partly in glass, and through the glazed panels the corridor behind the circle, and the doors admitting to the circle, are seen. The right-hand wall is panelled in a similar way, showing the landing at the top of the principal staircase and an entrance to the corridor. Some music-stands and stools are on the landing, arranged for a small orchestra.

In the right-hand wall there is a double swing-door giving on to the landing; and in the wall at the back, opening on to, and from, the corridor, there is a single swing-door on the left and another on the right. The left-hand door is fastened back into the saloon by a hook. Between the two doors in the back wall runs the refreshment-counter.

In one of the further corners of the saloon there is a plaster statue representing the Muse of Comedy, in the opposite corner a companion figure of Dancing. In the wall on the left, the grate hidden by flowers, is a fireplace with a fender-stool before it, and on either side of the fireplace there is a 70 capacious and richly upholstered arm-chair. A settee of like design stands against the wall on the right between the double-door and the spectator.

The counter is decked-out as a sideboard, and at equal distances from each other there are four round tables laid for a supper-party of twenty-six persons. There are eight chairs at one table and six at each of the others, the chairs being of the sort usually supplied by ball-caterers.

The saloon and the landing without are brilliantly lighted, the corridor less brightly.

Luigi and four waiters—one of whom has a curly head and a fair beard ending in two flamboyant points—are putting the finishing touches to the laying of the tables, while Morris Cooling, a person of imposing presence displaying a vast expanse of shirt-front, is engaged in placing upon each of the serviettes a card bearing the name of a guest.

Cooling.

Referring to a plan of the tables which he has in his hand. Miss Connify—Miss Connify—Miss Connify—where’s Miss Connify? Ah, here you are, my dear— moving to Miss Connify’s chair and putting a card upon her serviette next to old Arthur.

The four waiters, obeying a direction in dumb-show from Luigi, go out at the door on the left.

Luigi.

A little, dark, active man—viewing the tables with satisfaction. Tables look nice, Mr. Cooling?

71Cooling.

Absorbed. Not bad—not bad—not bad. Luigi follows the waiters. Miss Kato? Moving to another table and laying a card upon a serviette. Gabrielle.

Roper bustles in through the double-door, in high feather.

Roper.

Hul-lo! Cutting a caper. Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, and how are you to-morrow!

Cooling.

Deep in his plan of the tables. Hullo, Lal!

Roper.

Surveying the tables. Splendid! Going from one table to another. Seating ’em, hey?

Cooling.

Mr. Palk—Mr. Palk—Mr. Palk? Placing another card. Albert.

Roper.

Which d’ye make your principal table?

Cooling.

There it is; you’re at it.

Roper.

Ah, yes. Examining the cards. “Miss Lily Parradell—”! His jaw falling. Why, you’ve gone and put the Baron on her right!

72Cooling.

Unconsciously. Well, what’s the objection?

Roper.

Where’s Farncombe? Where’s Lord Farncombe?

Cooling.

On the other side, with Dolly Stidulph and Enid.

Roper.

Rats!

Cooling.

What do you mean by Rats? Advancing to the principal table—nettled. Look heah, Lal——!

Roper.

My dear fellow, Miss Parradell is the heroine o’ the party; the seat next to her is the seat of honour.

Cooling.

That’s why I’ve put the Baron there. With things as they are between England and Germany——

Roper.

If Germany doesn’t like it, she must lump it. Lord Farncombe’s the eldest son of an Earl; you can’t get over that.

Cooling.

Picking up Farncombe’s card. Oh, have it your own way.

73Roper.

Picking up Von Rettenmayer’s card. Besides, the Baron’s sweet on Enid just now; I’m sure he’d prefer— They exchange the cards and rearrange them. thanks, ol’ man. Sorry I was shirty.

Cooling.

Laying down his plan and cards and producing a letter from his breast-pocket. By-the-bye, the fair Lily—the heroine of the party, as you call her—is in a pretty tantrum over the whole business.

Roper.

Tantrum?

Cooling.

Unfolding the letter. Had this from her ten minutes ago. Listen to this. Reading. “My Dressing-room. 11-15. 80 degrees, with the windows open.” In an injured tone. Haw, so I should think!

Roper.

Concerned. What’s amiss?

Cooling.

Reading. “Morrie, you pig.” Roper whistles. “Morrie, you pig. I should feel deeply indebted to you if you would kindly inform me why the devil you went out of your way to deceive me last night. You led me to suppose—and so did that lying worm Lal Roper——” looking at Roper You.

74Roper.

Oh, lord!

Cooling.

Resuming. “—that lying worm Lal Roper——”

Roper.

Testily. All right, all right.

Cooling.

“—you both led me to suppose that this rotten banquet was to be a family gathering of the ladies and gentlemen of the Pandora Theatre, and no outsiders asked. Now I find that only three or four of the men of the Company are invited, and I hear from Nita Trevenna, who has got it from young Kennedy, that several of the Boys are to be laid on for the occasion. The result is you have made me tell a regular whopper to a particular friend of mine with regard to this affair——”

Roper.

Passing his hand over his brow. Nicko Jeyes.

Cooling.

“—which I will never forgive you for, Morris Cooling—neither you nor Lal Roper. As true as I am alive, I have a jolly good mind not to show, but to put on my old rags and go straight home. You are two cads. So take it out of that and believe me, Always yours affectionately, Lil.”

75Roper.

Walking about. Well, I’m blessed!

Cooling.

Returning the letter to his pocket. Haw! Tasty document!

Roper.

Lying worm and a cad! And from Miss Lily Margaret Upjohn! To Cooling. Done anything about it?

Cooling.

No; waited for you. Going on with his arrangements at the tables. You’re responsible. What I did last night was simply to oblige a pal.

Roper.

Irresolutely. I’d better run round to her, and try to smooth her down, hadn’t I?

Cooling.

Perhaps you had. Placing a card. Mr. Stewart Heneage. To Roper. Why you wanted to mislead the girl I can’t understand.

Roper.

Damn it, you agreed that that sulky brute Jeyes ’ud be a wet blanket! You blow hot and cold, you do!

Cooling.

There you go! More filthy temper!

76Roper.

If ever I assist in getting up another party——! As he reaches the door on the left, he encounters Carlton Smythe, who is entering at that moment, and puts on his humourous manner. Hul-lo! Here we are again! All change for Oxford Circus!

Smythe.

A bulky, sleepy-looking man with grey hair, a darker moustache and beard, and a heavy, rolling gait. Ha, Lal!

Roper.

I’m just going to have a word with Lil Parradell.

He disappears and Smythe advances.

Cooling.

Approaching Smythe. How are you to-night, Chief?

Smythe.

A silk hat on the back of his head, an overcoat on his arm—regarding the preparations with disgust. Puh! Here’s a muck and a muddle!

Cooling.

Don’t worry; we’ll clear it away in no time. Shall I tell you who are coming?

Smythe.

No; I shall know soon enough. What was the house to-night?

77Cooling.

Producing a long slip of paper and handing it to Smythe. Big. Smythe scans the paper through half-closed lids and gives a growl of contentment. Haw! And the weather dead against us.

Smythe.

Screwing up the paper, and cramming it into his waistcoat-pocket. There’s no bad weather for a good play. Looking at his hands. I’ll go and have a wash and brush up. Luigi returns, entering at the door on the left, and goes behind the counter. The waiters follow him, carrying some melons lying upon ice in plated dishes. They deposit the dishes upon the counter and Luigi proceeds to cut the melon into slices. Cooling resumes, at a table on the left, the placing of the cards. As Smythe is moving towards the right-hand door at the back, Stewart Heneage and Gerald Grimwood—two exquisitely dressed youths with blank faces—enter from the landing. Smythe shakes hands with them. Ha, Mr. Heneage! Ha, Mr. Grimwood! Heneage and Grimwood murmur some polite expressions. Excuse me; I’m just going to wash my hands. De Castro enters, also at the double-door, and Smythe shakes hands with him. Heneage and Grimwood drift over to Cooling, who hails them warmly. How do, Sam! Back in a moment; just going to wash my hands.

De Castro.

Detaining him. I thay, Carlton.

Smythe.

Eh?

78De Castro.

Lowering his voice. I’ve been in front again to-night. Magnifithent! Marvellouth!

Smythe.

Resignedly. It’ll do; I shall get a couple o’ years out of it.

De Castro.

There’th jutht one little improvement I’d like to thee, if I may thuggetht it.

Smythe.

What’s that?

De Castro.

Linking his arm in Smythe’s. You’re thure you won’t conthider me prethumptuouth?

Smythe.

Of course not; very kind of yer.

De Castro.

In Smythe’s ear. If you could give Gabth—Mith Kato—a tiny bit more to do in the thecond act——!

Smythe.

Nodding. Ah, yes, yes.

De Castro.

She’th a little lump o’ talent, that gal, if you only realithed it; a perfect little lump o’ talent.

79Smythe.

Trying to escape. Er—I’ll think it over.

De Castro.

Will yer! An extra thong! That’th all it need be—an extra thong! Oh, it would be thuch an improvement! Von Rettenmayer enters at the double-door. The waiters now go to the tables and lay a plate with a slice of melon upon it at each cover. Here’th the Baron. We’ve been thitting together to-night, I and the Baron. Wringing Smythe’s hand. Thankth. Joining Cooling and the others on the left as Smythe greets Von Rettenmayer. Hullo, Morrith! Shaking hands with Heneage and Grimwood. Well, boyth!

Smythe.

Shaking hands with Von Rettenmayer. Glad to see yer, Baron.

Von Rettenmayer.

Zo good of you to haf me.

Smythe.

Excuse me; I’m just going to wash my hands.

Von Rettenmayer.

Detaining him. Bardon me—one moment——

Smythe.

Eh?

Von Rettenmayer.

Dropping his voice. May I dake the liberdy of 80 indulging in a liddle griticism on your eggcellent blay?

Smythe.

Certainly.

Von Rettenmayer.

Drawing Smythe away from the tables. Gome here. His mouth close to Smythe’s ear. The zecond aggd!

Smythe.

Second act; what’s the matter with it?

Von Rettenmayer.

The pard where the gharming Miss Barradell is ghanging her gostume——

Smythe.

Yes?

Von Rettenmayer.

That is where the biece reguires lifding— with a gesture lifding.

Smythe.

Lifting?

Von Rettenmayer.

Mr. Davish—Mr. Balk—eggsdremely glever; slipping his arm through Smythe’s but if you could zee your way glear to gif Enid—Miss Mongreiff—anoder dance——

Smythe.

Nodding. Ah, h’m, h’m.

81Von Rettenmayer.

It would remove the zolitary imberfection.

Smythe.

Er—I’ll think it over. Releasing himself. I’m just going to wash my hands. We’ll talk about it later.

Von Rettenmayer.

Schoensten Dank. Going to the men on the left. Aha, Mr. Gooling! My dear Steward—my dear Jerry——!

As Smythe is again making for the door on the left, Mrs. Stidulph enters from the landing with Colonel Stidulph.

Smythe.

To Mrs. Stidulph. Ha, Dolly! Kissing her. How are you, my dear?

Mrs. Stidulph.

A mature but still beautiful woman, gorgeously dressed and wearing showy jewels—with a lofty air. How are you, Carlton?

Smythe.

To Stidulph. How d’ye do, Arthur? Delighted to see yer.

Mrs. Stidulph.

Lucky I’m able to come to you to-night. It’s so difficult to catch me in the season.

82Smythe.

Been in front?

Mrs. Stidulph.

M’yes; in a tone of boredom oh, yes.

Smythe.

What, don’t you like it?

Mrs. Stidulph.

Oh, I don’t say I dislike it; shrugging her shoulders but one can’t forget what one used to do here in the old days.

Stidulph.

An elderly, distinguished-looking man with a meek voice and a courteous but rather nervous manner. I’ve had a most enjoyable evening, Carlton. So bright; so very bright!

Mrs. Stidulph.

To Stidulph, sneeringly. Oh, anything pleases you; you’d laugh at Punch and Judy.

Smythe.

I’m just running away to wash my hands. Looking towards the men on the left. You know Von Rettenmayer?

Mrs. Stidulph.

Know him! Why, he was about in my time! Crossing to Von Rettenmayer, followed by Stidulph. Karl!

83Von Rettenmayer.

My dear lady! Kissing her hand perfunctorily. What bliss! Shaking hands with Stidulph. Golonel!

Mrs. Stidulph.

Shaking hands with de Castro. How are you, Sam?

De Castro.

Ah, Dolly! To Stidulph. Hullo, Arthur!

Cooling.

Presenting Heneage and Grimwood to the Stidulphs. Mr. Stewart Heneage—Mr. Gerald Grimwood——