This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Set in Silver

Author: Charles Norris Williamson and Alice Muriel Williamson

Release Date: September 30, 2006 [eBook #19412]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SET IN SILVER***

Audrie

With all admiration we dedicate our story

of a tour in the land he loves

"... this little world,

This precious stone, set in the silver sea

That serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England."

I

AUDRIE BRENDON TO HER MOTHER

AT CHAMPEL-LES-BAINS, SWITZERLAND

Rue Chapeau de Marie Antoinette,

Versailles,

July 4th

Darling Little French Mother: Things have happened. Fire-crackers! Roman candles! rockets! But don't be frightened. They're all in my head. Nevertheless I haven't had such a Fourth of July since I was a small girl in America, and stood on a tin pail with a whole pack of fire-crackers popping away underneath.

Isn't it funny, when you have a lot to tell, it's not half as easy to write a letter as when you've nothing at all to say, and must make up for lack of matter by weaving phrases? Now, when I'm suffering from a determination of too many words to my pen, they all run together in a torrent, and I don't know how to make them dribble singly to a beginning.

I think I'll talk about other things first. That's the way dear Dad used to do when he had exciting news, and loved to dangle it over our heads, "cherry ripe" fashion, harping on the weather or the state of the stock-market until he had us almost dancing with impatience.

Yes, I'll dwell on other things first—but not irrelevant things, for I'll dwell on You—with a capital Y, which is the only proper way to spell You—and You are never irrelevant. You couldn't be, whatever was happening. And just now you're particularly relevant, though you're far off in nice, cool Switzerland; for presently, when I come to the Thing, I'm going to ask your advice.

It's very convenient having a French mother, and I do appreciate dear Dad's Yankee cleverness in securing you in the family. You say sometimes that I seem all American, and that you're glad; which is pretty of you, and loyal to father's country, but I'm not sure whether I shouldn't have preferred to turn out more like my mamma. You're so complete, somehow—as Frenchwomen are, at their best. I often think of you as a kind of pocket combination of Somebody's Hundred Best Books: Romance, Practical Common Sense, Poetry, Wit, Wisdom, Fancy Cookery, etc., etc.

Who but a Frenchwoman could combine all these qualities with the latest thing in hair-dressing and the neatest thing in stays? By the way, can one's stays be a quality? Yes, if one's French—even half French—I believe they can.

If I hadn't just got your letter of day before yesterday, assuring me that you feel strong and fresh—almost as if you'd never been ill—I shouldn't worry you for advice. Only a few weeks ago, if suddenly called upon for it, you'd have shown signs of nervous prostration. I shall never forget my horror when you (quite uncontrollably) threw a spoon at Philomene who came to ask whether we would have soup à croute or potage à la bonne femme for dinner!

Switzerland was an inspiration; mine, I flatter myself. And if, in telling me that you're in robust health again, you're hinting at an intention to sneak back to blazing Paris before the middle of September, you don't know your Spartan daughter. All that's American in me rises to shout "No!" And you needn't think that your child is bored. She may be boiled, but never bored. Far from it, as you shall hear.

School breaks up to-morrow—breaks into little blond and brunette bits, which will blow or drift off to their respective homes; and I should by this time be packing to visit the Despards, where I'm supposed to teach Mimi's young voice to soar, as compensation for holiday hospitality; but—I'm not packing, because Ellaline Lethbridge has had an attack of nerves.

You won't be surprised that I stopped two hours over-time to-day to hold the hand and to stroke the hair of Ellaline. I've done that before, when she had a pain in her finger, or a cold in her little nose, and sent you a petit bleu to announce that I couldn't get home for dinner and our happy hour together. No, you won't be surprised at my stopping—or that Ellaline should have an attack of nerves. But the reason for the attack and the cure she wants me to give her: these will surprise you.

Why, it's almost as hard to begin, after all, as if I hadn't been working industriously up to it for three pages. But here goes!

Dearest, you've often said, and I've agreed with you (or else it was the other way round), that nothing I could ever do for Ellaline Lethbridge would be too much; that she couldn't ask any sacrifice of me which would be too great. Of course, one does say these things until one is tested. But—I wonder if there is a "but"?

Of course you believe that your one chick has a glorious voice, and that it's a cruel shame she should be doing nothing better than teaching other people's chicks to squall, whether their voices are worth squalling with or not. Perhaps, though, mine mayn't be as remarkable an organ as we think; and even if you hadn't made me give up trying for light opera, because I received one Insult (with a capital I) while I was Madame Larese's favourite pupil, I mightn't in any case have turned into a great prima donna. I was rather excited and amused by the Insult myself—it made me feel so interesting, and so like a heroine of romance; but you didn't approve of it; and we had some hard times, hadn't we, after all our money was spent in globe-trotting, and lessons for me from the immortal Larese?

If it hadn't been for meeting Ellaline, and Ellaline falling a victim to my modest charms, and insisting upon Madame de Maluet's taking me as a teacher of singing for her "celebrated finishing school for Young Ladies," what would have become of us, dearest, with you so delicate, me so young, and both of us so poor and alone in a big world? I really don't know, and you've often said you didn't.

Of course, if it hadn't been for Ellaline—Madame's richest and most important girl—persisting as she did, in her imperious, spoiled-child way, Madame wouldn't have dreamed of engaging a young girl like me, without any experience as a teacher, no matter how much she liked my voice and my (or rather Larese's) method. I suppose no one would else have risked me; so I certainly do owe to Ellaline, and nobody but Ellaline, three happy and (fairly) prosperous years. To be sure, because of my position at Madame de Maluet's, I have got a few outside pupils; but that's indirectly through Ellaline, too, isn't it?

I'm reminding you of all these things so that you may have it clearly before your mind just how much we do owe Ellaline, and judge whether the payment she now asks is too big or not.

That's the way she puts it, not coarsely or crudely; but I know how she feels.

She sent me a little note yesterday, while I was giving a lesson, to say she'd a horrid headache, had gone to bed, and would I come to her room as soon as I could. Well, I went at lunch time, for I hated to keep her waiting, and thought I could eat later. As it turned out, I didn't eat at all. But that's a detail.

She had on a perfectly divine nighty, with low neck and short sleeves (no girl would be allowed to wear such a thing in any but a French school, I'm sure, even if she were a "parlour boarder") and her hair was in curly waves over her shoulders. Altogether she looked adorable, and about fourteen years old, instead of nearly nineteen, as she is.

"You don't show your headache a bit," said I.

"I haven't got one," said she.

Then she explained that she'd been dying for a chance to talk with me alone, and the headache was the only thing that occurred to her in the circumstances. She doesn't mind little fibs, you know. Indeed, I believe she rather likes them, because any "intrigue," even the smallest, is exciting to her.

You would never guess anything like what has happened.

That dragon of a guardian of hers is coming back at last from Bengal, where he's been governor or something. Not that his coming would matter particularly if it weren't for complications, but there are several, the most formidable of which is a Young Man.

The Young Man is a French young man, and his name is Honoré du Guesclin. He is a lieutenant in the army (Ellaline mentioned the regiment with pride, but I've forgotten it already, there was so much else to remember), and she says he is descended from the great Du Guesclin. She met him at Madame de Blanchemain's—you remember the Madame de Blanchemain who was Ellaline's dead mother's most intimate friend, and who lives at St. Cloud? Ellaline has spent all her holidays there ever since I've known her; but though I thought she told me everything (she always vowed she did), not a word did she ever breathe about a young man having risen over her horizon. She says she didn't dare, because I'm so "queer and prim about some things." I'm not, am I? But now she's driven to confess, as she's in the most awful scrape, and doesn't know what will become of her and "darling Honoré," unless I'll consent to help them.

She met him only last Easter. He's a nephew of Madame de Blanchemain's, it seems; and on coming back from foreign service in Algeria, or somewhere, he dutifully paused to visit his relative. Of course it occurs to me, did Madame de Blanchemain write and intimate that she would have in the house a pretty little Anglo-French heiress, with no inconvenient relatives, unless one counts the Dragon? But Ellaline says Honoré's coming was quite a surprise to his aunt. Anyway, he proposed on the third day, and Ellaline accepted him. It was by moonlight, in a garden, so who can blame the poor child? I always thought if even a moderately good-looking young man proposed to me by moonlight, in a garden, I would say "Yes—yes!" at once, even if I changed my mind next day.

But Honoré is very good looking (she has his picture in a locket, with such a turned-up moustache—I mean Honoré, not the locket), and so Ellaline didn't change her mind next day.

Not a word was said to Madame de Blanchemain (as far as Ellaline knows), for they decided that, considering everything, they must keep their secret, and eventually run away to be married; because Honoré is poor, and Ellaline's an heiress guarded by a Dragon.

Well, through letters which E. has been receiving at a teashop where she and the other older girls go, rigorously chaperoned, twice a week, it was arranged to do the deed as soon as school should close; and if they could have carried out their plan, Ellaline would have been Madame du Guesclin before the Dragon could have appeared on the scene, breathing fire and rattling his scales. They were going to Scotland to be married (Honoré's idea), as a man can't legally marry a girl under age in France without the consent of everybody concerned. Once she'd got away with him, and had had any kind of hole-in-the-corner wedding, Honoré was of opinion that even the most abandoned Dragon would be thankful to sanction a marriage according to French law; so it could all be done over again properly in France.

I suppose this appealed immensely to Ellaline's love of intrigue and kittenish tricksiness generally. Anyway, she agreed; but young officers propose, and their superiors dispose. Honoré was ordered off for a month's manœuvres before he could even ask for leave; and as he's known to be destitute of near relatives, he couldn't rake up a perishing grandmother as an excuse.

What he did try, I don't know; but anyhow, he failed, and the running away had to be put off. That was blow number one, and could have been borne, without blow number two, which fell in the shape of a letter. It said that the wicked guardian was just about to start for home, and intended to pick up Ellaline on his way to England, as if she were a parcel labelled "to be kept till called for."

She's certain he won't let her marry Honoré if he has the chance to say "no" beforehand, because he cares nothing about her happiness, or about her, or anything else except his own selfish ambitions. Of course, Ellaline is a girl who takes strong prejudices against people for no particular reason, except that she has a "feeling they are horrid"; but she does appear to be right about this man. He's English, and though Ellaline's mother was half French, they were cousins, and I believe her dying request was that he should take care of her daughter and her daughter's money. You would have thought that that must have softened even a hard heart, wouldn't you? But the Dragon's was evidently sentiment-proof, even so many years ago, when he must have been comparatively young—if Dragons are ever young.

He accepted the charge (Ellaline thinks her money probably influenced him to do that; and perhaps he was paid for his trouble); but, instead of carrying out his engagements, like a faithful guardian, he packed the poor four-year-old baby off to some pokey, prim people in the country, and promptly went abroad to enjoy himself. There Ellaline would no doubt have been left to this day, dreadfully unhappy and out of her element, for the people were an English curate and his wife; but, luckily, her mother had stipulated that she was to be sent to the same school in France where she herself had been educated—Madame de Maluet's.

Never once has her guardian shown the slightest sign of interest in Ellaline: hasn't asked for her photograph or written her any letters. They've communicated with each other only through Madame de Maluet, four times a year or so; and Ellaline doesn't feel sure that her fortune has been properly administered, so she says she ought to marry young and have a husband to look after her interests.

When I ventured to hope that the Dragon wasn't quite so scaly and taily as she painted him, she proved her point by telling me that he'd been censured lately in the English Radical papers for killing a lot of poor, defenceless Bengalese in cold blood. Somebody must have sent her the cuttings, for Ellaline hardly knows that newspapers exist. I dare say it was Kathy Bennett, one of Madame's few English pupils. Ellaline has chummed up with her lately. And that news does seem to settle the man's character, doesn't it? He must be a perfect brute.

Ellaline says that she'd rather die than lose Honoré, also that he'll kill himself if he loses her. And now, dearest—now for the Thunderbolt! She vows that the only thing which can possibly save her is for me to take her place for five or six weeks, until her soldier's manœuvres are over and he can get leave to whisk her off to Scotland for the wedding.

You're the quickest-witted darling in the world, and you generally know all that people mean even before they speak. Yet I can see you looking puzzled as well as startled, and muttering to yourself: "Take Ellaline's place? Where—how—when?"

I was like that myself while she was trying to explain. I stared with an owlish stare for about five minutes, until her real idea in all its native wildness, not to say enormity, burst upon me.

She wants to go day after to-morrow to Madame de Blanchemain's, as she'd expected to do before she heard that the Dragon was coming to gobble her up. She wants to stay there quietly until Honoré can take her, and she wants me to pretend to be Ellaline Lethbridge!

I nearly fell off my chair at this point, but I hope you won't do anything like that—which is the reason why I've been working up to the revelation with such fiendish subtlety. Have you noticed it?

Ellaline has plotted the whole scheme out. I shouldn't have thought her capable of it; but she says it's desperation.

She's certain she can persuade Madame de Maluet to let her leave school, to go to the station and meet the Dragon (that's the course he himself suggests: too much trouble even to run out to Versailles and fetch her) with only me as chaperon. I dare say she's right about Madame, for all the teachers will be gone day after to-morrow, and Madame herself invariably collapses the moment school breaks up: she seems to break up with it, and to have to lie in bed for at least half a week to be mended.

Madame has really quite a flattering opinion of my discretion. She's told me so several times. I suppose it's the way I do my hair for school, which does give me a look of incorruptible virtue, doesn't it? Fortunately she doesn't know I always change it (if not too tired) ten minutes after I get home to you.

Well, then, taking Madame's permission for granted, Ellaline points out that all stumbling-blocks are removed, for she won't count moral ones, or let me count them.

I'm to see her off for St. Cloud, and wait to receive the Dragon. "Sir, behold the burnt-offering—I mean, behold your ward!"

And I'm to go on being a burnt-offering till it's convenient for the real Ellaline to scrape my ashes off the smoking altar.

It's all very well to make fun of the thing like that. But to be serious—and goodness knows it's serious enough—what's to be done, little mother? Ellaline has (because I insisted) given me till to-morrow morning to answer. I explained that my consent must depend on your consent. So that's why I haven't had anything to eat since breakfast. I rushed home to write this immense letter to you, and get it off to catch the post. It will arrive in the morning with your coffee and petits pains—how I wish I were in its place! You can take half an hour to make up your mind (I'm sure with your lightning wits you wouldn't ask longer to decide the fate of the Great Powers of Europe) and then telegraph me simply "Yes," or "No." I will understand.

For my own sake, naturally, I should prefer "No." That goes unsaid, doesn't it? I should then be relieved of responsibility; for even Ellaline, knowing that you and I are all in all to each other, could hardly expect me to fly in your face, just to please her. But, on the other hand, if you did think I could do this dreadful thing without thereby becoming myself a Dreadful Thing, it would be a glorious relief to pay my debt of gratitude to Ellaline, yes, and even over-pay it, perhaps. One likes to over-pay a debt that's been owing a long time, for it's like adding an accumulation of interest that one's creditor never expected to get.

When, gasping after the first shock, I pleaded that I'd do anything else, make any other sacrifice for Ellaline's sake, except this one, she flashed out (with the odd shrewdness which lurks in her childishness like a bright little garter-snake darting its head from a bed of violets), saying that was always the way with people. They were invariably ready to do for their best friends, to whom they were grateful, anything on earth except the only thing wanted.

Well, I had no answer to make; for it's true, isn't it? And then Ellaline sobbed dreadfully, clutching at me with little, hot, trembling hands, crying that she'd counted on me, that she'd been sure, after all my promises, I wouldn't fail her. She'd felt so safe with me! Are you surprised I hadn't the heart to refuse? I confess, dear, that if I were quite alone in the world (though the world wouldn't be a world without you) I should certainly have grovelled and consented then and there.

She says she won't close her eyes to-night, and I dare say she won't, in which case she'll be as pathetic as a broken flower to-morrow. I don't think I shall sleep much either, wondering what your verdict will be.

I really haven't the remotest idea whether it will be Yes or No. Usually I imagine that I can pretty well guess what your opinion is likely to be, but I can't this time. The thing to decide upon is in itself so fantastic, so monstrous, that one moment I tell myself you won't even consider it. The next minute I remember what a dear little "crank" you are on the subject of gratitude—your "favourite virtue," as you used to write in old-fashioned "Confession Albums" of provincial American friends when I was a child.

If people do anything nice for you, you run your little high-heeled shoes into holes to do something even nicer for them. If you're invited out to tea, you ask your hostess to lunch or dinner, in return: that sort of thing invariably; and you've brought me up with the same bee in my bonnet. So what will your telegram be?

Whatever you say, you may count on a meek "Amen, so be it," from

Your most admiring subject,

Audrie.

P. S.—Of course, it isn't as if this man were an ordinary, nice, inoffensive human man, is it? I do think that almost any treatment is too good for such a cold-blooded, supercilious old Dragon. And you needn't reprove me for "calling names." With singular justice Providence has ticketed him as appropriately as his worst enemy would have dared to do. They have such weird names in Cornwall, don't they?—and it seems he's a Cornishman. Until lately he was plain Mister, now he's Sir Lionel Pendragon. Somebody has been weak enough to die and leave him a title, and also an estate (though not in Cornwall) which he's returning to England in greedy haste to pounce upon. So characteristic, after living away all these years; though Madame de Maluet has tried to make Ellaline believe he's coming back to settle down because of a letter she wrote, reminding him respectfully that after nineteen it's almost indecent for a girl to be kept at school.

Don't fear, however, if your telegram casts me to the Dragon, that I shall be in danger of getting eaten up. His Dragonship, among other stodgy defects, has that of eminent, well-nigh repulsive, respectability. He is as respectable as a ramrod or a poker, and very elderly, Ellaline says. From the way she talks about him he must be getting on for a hundred, and he is provided with a widowed sister, a Mrs. Norton, whom he has dug up from some place in the country to act as chaperon for his ward. All other women he is supposed to detest, and would, if necessary, beat them off with a stick.

II

AUDRIE BRENDON TO HER MOTHER

Rue Chapeau de Marie Antoinette,

Versailles,

July 5th

My Spartan Angel: Now the telegram's come, I feel as if I'd known all along what your decision would be.

I'm glad you were extravagant enough to add "Writing," for to-morrow morning I shall know by exactly what mental processes you decided. Also, I'm glad (I think I'm glad) that the word is "Yes."

It's afternoon now; just twenty-four hours since I sat here in the same place (at your desk in the front window, of course), trying my best to put the situation before you, as a plain, unvarnished tale.

I stuck the bit of blue paper under Ellaline's nose, and she almost had a fit with joy. If she were bigger and more muscular, she'd have kissed and squeezed the breath of life out of me, which would have been awkward for her, as she'd then have been thrown back upon her own resources.

Oh, ma petite poupee de Mere, only think of it! I go to-morrow—into space. I disappear. I cease to exist pro tem. There will be no me, no Audrie, but, instead, two Ellalines. I've often told her, by the way, that I would make two of her. Evidently I once had a prophetic soul. I only wish I had it still, so I might see beforehand what will happen to the Me-ness of Ellaline in the next few weeks. Anyhow, whatever comes, I expect to be supported by the consciousness that I'm paying a debt of gratitude as perhaps such a debt was never paid before.

Of course I shall have a perfectly horrid time. Not only shall I be wincing under the degrading knowledge that I'm a base pretender, but I shall be wretchedly homesick and bored within an inch of my life. I shall be, in the sort of environment Ellaline describes, like a mouse in a vacuum—a poor, frisky, happy, out-of-doors field-mouse, caught for an experiment. When the experiment is finished I shall crawl away, a decrepit wreck. But, thank heaven, I can crawl to You, and you will nurse me back to life. We'll talk everything over, for hours on end, and I'll be able to abuse the Dragon to my heart's content. I know you'll let me do that, provided I don't use naughty words, or, if any, disguise them daintily in a whisper.

Ellaline and I have discussed plans and possibilities, and if all goes as she expects (I don't see why it shouldn't), I ought to be freed from the unpleasant rôle of understudy in five or six weeks. The instant my chains are broken by a telegram from the bride saying, "Safely married," or words to that effect, I shall do "all my possible" to fold, my tent like an Arab and silently steal—not to say sneak—away from the lair of the Dragon, without his opening a scaly red eye to the dreadful reality, until I'm beyond his power.

It must be either that or the most awful scene with him—a Regular Row. He, saying what he thinks of my deception; me, defending myself and the real Ellaline by saying what I think of his general beastliness. If it came to that, I might in my rage wax unladylike; so perhaps, of the two evils, the lesser would be the sneak act—n'est ce pas? Well, I shall see when the time comes.

In five or six weeks I had thought, in any case, of allowing you to leave Champel-les-Bains, should you grow too restive lacking my society. I thought of proposing by then, if you were sufficiently braced by Swiss air, milk, and honey and Champel douches, that we should join forces at a cheap but alluring farmhouse somewhere.

That idea may still fit in rather well, mayn't it? But if, for any unforeseen reason, I should have to stay sizzling on the sacrificial altar longer than we expect, you mustn't come home to hot Paris to economize and mope in the flat. You must stop in Switzerland till I can meet you in some nice place in the country. Promise that you won't add to my burdens by being refractory.

I'll wire you an address as soon as I am blessed—or cursed—with one. And whatever you do, don't forget that I'm merged in Ellaline Lethbridge. If her identity fits me as badly as her dresses would do it will come about down to my knees and won't meet round the waist.

As soon as I have your letter to-morrow morning, dearest, I'll write again, if only a few lines. Then, when I've seen the Dragon and have gained a vague idea how and where he means to dispose of his prey, I'll scribble off some sort of description of the man and the meeting, even if it's on board the Channel boat, in the midst of a tossing.

Your

Iphegenia.

(Or would Jephtha's daughter be more appropriate? I'm not quite sure how to spell either.)

III

AUDRIE BRENDON TO HER MOTHER

Rue Chapeau de Marie Antoinette,

July 6th. Early Morning

Dearest Dame Wisdom: You ought to be Adviser-in-Chief to Crowned Heads. You'd be invaluable; worth any salary. What a shame you aren't widely known: a sort of public possession! But for my sake I'm glad you aren't, because if you were discovered you'd never have a spare minute to advise me.

Of course, dear, if you hadn't reached your conclusions just as you did about this step you wouldn't have counselled, or even allowed, me to take it. And I will remember every word you say. I'll do exactly as you tell me to do. So now, don't worry, any more than you would if I were an experienced and accomplished young parachutist about to make a descent from the top of the Eiffel tower.

It's eight o'clock, and I've satisfied my soul with your letter and my body with its morning roll and coffee. When I've finished scribbling this in pencil to you, I shall pack, and be ready—for anything.

By the way, that reminds me. What a tangled web we weave when first we practise to deceive, etc.

Won't the Dragon think it queer that his rich ward should make no better toilettes than I shall be able to produce—after living at Versailles, practically in Paris, with a huge amount of spending money—for a schoolgirl?

I thought of that difficulty only last night for the first time, after I was in bed, and was tempted to jump up and review my wardrobe. But it was unnecessary. Not only could I call to mind in the most lively way every dress I have, but, I do believe, every dress I ever did have since my frocks were let down or done over from yours. I suppose that ought to make me feel rather young, oughtn't it? To remember every dress I ever owned? But it doesn't. I'll be twenty-one this month, you know—a year older than you were when your ears were gladdened by my first howl. I'm sure it was unearthly, yet that you said at once to Dad: "The dear child is going to be musical!"

But to return to the wardrobe of the heiress's understudy. It consists of my every-day tailor-made, two white linen coats and skirts, a darned collection (I don't mean that profanely) of summer blouses, and the everlasting, the immortal, black evening dress. Is it three or four years old? I know it was my first black, and I did feel so proud and grown-up when you said I might have it.

You'll be asking yourself: "Where is the blue alpaca she bought in the Bon Marché sale, which was in the act of being made when I left for la Suisse?" Up to now I've concealed from you the tragical fact that that horrid little Mademoiselle Voisin completely spoiled it. I was so furious I could have killed her if she'd been on the spot. There is no rage like the dress rage, is there?

My one hope is that the Dragon may take as little interest in Ellaline's clothes as he has taken in Ellaline's self, or that, being used to the costumes of the Bengalese, which, perhaps, are somewhat sketchy, he may be thankful that his ward has any at all.

You see, I can't tell Ellaline about this, because she couldn't help thinking it a hint for her to supply the deficiency, and I wouldn't let her do that, even for her own credit. Anyhow, there'd be no time to get things, so I must just do the best I can, and carry off the old gray serge and sailor hat with a stately air. Heaven gave me five foot seven and a half on purpose to do it with.

Now I must pack like heat-lightning; and when I've finished I shall send the brown box and the black Gladstone to the Gare de Lyon, where he will arrive from Marseilles. That is rather complicated, as of course we must go to the Gare du Nord for Calais or Boulogne; but he mayn't wish to start at once for England, and in my new character, as his ward, I must be prepared to obey his orders. I hope he won't treat me as he seems to have treated the Bengalese! The luggage of Miss Ellaline Lethbridge obviously can't be called for at the flat of Mrs. Brendon and her daughter Audrie, for there would be questions—and no proper answers. Therefore, when I present myself at the Gare de Lyon, I intend to be "self-contained." All my worldly goods will be there, to be disposed of as the Grand Mogul pleases.

When I've packed I shall hie me to Madame de Maluet's, looking as good and meek as a trained dove, to take charge of Ellaline—and to change into Ellaline.

After that—the Deluge.

Good-bye, darling!

Me, to the Lions!

But I shall have your talisman-letter in my pocket, I can't be eaten, though I do feel rather like

Your

Martyr Child

IV

AUDRIE BRENDON TO HER MOTHER

On Board the Boat, half-Channel over,

July 6th. Night

Mother Dear: The dragon-ness doesn't show at all on the outside.

I expected to meet a creature of almost heraldic grimness—rampant, disregardant, gules. What I did meet—but I'm afraid that isn't the right way to begin. Please consider that I haven't begun. I'll go back to the time when Ellaline and her chaperon (me) started away from school together in a discreet and very hot cab with her trunks.

She was jumpy and on edge with excitement, and got on my nerves so that it was the greatest relief when I'd seen her off in her train for St. Cloud. Just at this point I find another break in my narrative, made by a silly, not at all interesting, adventure.

I'd been waving my hand for the twenty-fifth time to Ellaline, in response to the same number of waves from her. When at last she drew in her head, as the train steamed away, I turned round in a hurry lest she should pop it out again, and bumped into a man, or what will be a man in a few years if it lives. I said, "Pardon, monsieur," as gravely as if it were a man already, and it said in French made in England that 'twas entirely its fault. It was such a young youth, and looked so utterly English, that I smiled a motherly smile, and breathed, "Not at all," as I passed on, fondly thinking to pass forever out of its life at the same time. But, dearest, the absurd little thing didn't recognize the smile as motherly. Perhaps it never had a mother. I had hardly observed it as an individual, I assure you, except as one's sub-conscious self takes notes without permission from headquarters. I was vaguely aware that the creature with whom I had collided was quite nice-looking, though bullet-headed, freckled, light-blue-eyed, crop-haired, and possessing the shadow of a coming event in the shape (I can't call it more) of a moustache. I had also an impression of a Panama hat, which came off in compliment to me, a gray flannel suit, the latest kind of collar (you know "Sissy Williams says, 'the feeling is for low ones this year'!") and mustard-coloured boots. All that sounds hideous, I know, yet it wasn't. At first sight it was rather attractive, but it lost its attractiveness in a flash when it mistook the nature of my smile.

You wouldn't believe that a nice, clean little British face could change so much for the worse in about the eighth part of a second! It couldn't have taken longer, or I shouldn't have seen, because it happened between my smile and my walking on. But I did see. A disagreeable kind of lighting up in the eyes, which instantly made them look full of—consciousness of sex, is the only way I can express it. And instead of being inoffensive, boyish, blue beads, they were suddenly transformed into the sharp, whitey-gray sort that the Neapolitans "make horns" at.

Well, all that was nothing to fuss about, for even I know that misguided youths from Surbiton or Pawtucket, who are quite harmless at home, think they owe it to themselves to be gay dogs when they run over to Paris, otherwise they'll not get their money's worth. If it hadn't been for what came afterward I wouldn't be wasting paper and ink on a silly young bounder. As it is, I'll just tell you what happened and see if you think I was to blame, or whether there's likely to be any bother.

At that change my look slid off the self-conceited face, like rain off a particularly slippery duck's back. He ought to have known then, if he hadn't before, that I considered him a mere It, but I can just imagine his saying to himself: "This is Paris, and I've paid five pounds for a return ticket. Must have something to tell the chaps. What's a girl doing out alone?"

He came after me and said I'd dropped something. So I had. It was a rose. I was going to disclaim it, with all the haughty grace of a broomstick, when suddenly I remembered that it was my carte d'identité, so to speak. The Dragon had prescribed it in his last letter to Madame de Maluet about meeting Ellaline. As there might be difficulty in recognition if she came to the station with a chaperon as strange to him as herself, it would be well, he suggested, that each pinned a red rose on her dress. Then he would look out for two ladies with two roses.

I couldn't make myself into two ladies with two roses, but I must be one lady with one rose, otherwise the Dragon and I might miss each other, and he would go out to Versailles to see what the dickens was the matter. Then the fat would be in the fire, with a vengeance!

You see, I had to say "Yes" to the rose, because there wasn't time to call at a florist's and try to buy another red label before going on to the Gare de Lyon. I put out my hand with a "thank you" that sounded as if it needed oiling, but, as if on second thought the silly idiot asked if he might keep the flower for himself. "It looks like an English rose," said he, with a glance which transferred the compliment to me.

"Certainly not—sir," said I. "I need it myself."

"If that's all, you might let me give you a whole bunch to make up for it," said he.

Then I said, "Go away," which mayn't have been elegant, but was to the point. And I walked on with long steps toward the place where there were cabs. But quite a short man is as tall as a tall girl, and his steps were as long as mine.

"I say," said he, "you needn't be so cross. What's the harm, as long as we're both English, and this is Paris?"

"I'm not English," I snapped. "If you don't go away I'll call a gendarme."

"You will look a fool if you do. A great tall girl like you," said he, trying to be funny. And it did sound funny. I suppose I must have been pretty nervous, after all I'd gone through with Ellaline, for I almost giggled, but I didn't, quite. On the contrary, I marched on like a war-cloud about to burst, and proved my non-British origin by addressing a cabman in the Parisian French I've inherited from you. I hoped that the boy couldn't understand, but he did.

"Mademoiselle, I have to go to the Gare de Lyon, too," he announced, "and it would be a very friendly act, and show that you forgive me, if you'd let me take you there in a taxi-motor, which you'll find much nicer than that old Noah's ark you're engaging."

"I don't forgive you," I said, as I mounted into the alleged ark. "Your only excuse is that you're not grown up yet."

With that Parthian shot I ordered my cocher, who was furtively grinning by this time, to drive on as quickly as possible.

Of course the horrid child from Surbiton or somewhere didn't have to go to the Gare de Lyon; but evidently he regarded me as his last hope of an adventure before returning to his native heath or duckpond; so, naturally, he followed in a taxi-motor, whose turbulent, goodness-knows-what-horse-power had to be subdued to one-half-horse gait. I didn't look behind, but I felt in my bones—my funny bones—that he was there. And when I arrived at the Gare de Lyon so did he.

The train I'd come to meet was a P. and O. Special, or whatever you call it, and it wasn't in yet, so I had to wait.

"Cats may look at kings," said my gay cavalier.

"Cads mayn't though," said I. Perhaps I ought to have maintained a dignified silence, but that mot was irresistible.

"You are hard on a chap," said he. "I tell you what. I've been thinking a lot about you, mademoiselle, and I believe you're up to some little game of your own. When the cat's away the mice will play. You've got rid of your friend, and you're out for a lark on your own. What?"

Oh, wouldn't I have loved to box his ears! But this time I was dignified and turned my back on him. Luckily, the train came puffing into the station, and he ceased to bother me actively, for the time; but the worst is to follow.

Now I think I've got to the part of my story where the Dragon ought to appear.

Suddenly, as the train stopped, that platform of a Paris railway station was turned into a thoroughly English scene. A wave from Great Britain swept over it, a tall and tweedy wave, bearing with it golf clubs and kitbags and every kind of English flotsam and jetsam. All the passengers had lately landed from the foreignest of foreign parts, coral strands, and that sort of remote thing, but they looked as incorruptibly, triumphantly British, every man, woman, and child of them (except a fringe of black or brown servants), as if they had strolled over from across Channel for a Saturday to Monday in "gay Paree." One can't help admiring as well as wondering at that sort of ineradicable, persistent Britishness, can one? I believe it's partly the secret of Great Britain's success in colonizing. Her people are so calmly sure of their superiority over all other races that the other races end by believing it, and trying to imitate their ways, instead of fighting to maintain the right to their own.

That feeling came over me as I, a mere French and American chit, stood aside to let the wave flow on. Everyone looked so important, and unaware of the existence of foreigners, except porters, that I was afraid my particular drop of the wave might sail by on the crest, without noticing me or my red rose. I tried to make myself little, and the rose big, as if it were in the foreground and I in the perspective, but the procession moved on and nobody who could possibly have been the Dragon wasted a glance on me.

Toward the tail end, however, I spied two men coming, followed by a small bronze figure in "native" dress of some sort. One of the two was tall and tanned, and thirty-five or so. The other—I had a bet with myself that he was my Dragon. But it was like "betting on a certainty," which is one of the few things that's dull and dishonest at the same time. Some men are born dragons, while others only achieve dragonhood, or have it thrust upon them by the gout. This one was born a dragon, and exactly what I'd imagined him, or even worse, and I was glad that I could conscientiously hate him in peace.

The other man had the walk so many Englishmen have, as if he were tracking lions across a desert. I quite admire that gait, for it looks brave and un-self-conscious; but the old thing labelled "Dragon" marched along as if trampling on prostrate Bengalese. A red-hot Tory, of course—that went without saying—of the type that thinks Radicals deserve hanging. In his eyes that stony glare which English people have when they're afraid someone may be wanting to know them; chicken-claws under his chin, like you see in the necks of elderly bull dogs; a snobbish nose; a bad-tempered mouth; age anywhere between sixty and a hundred. Altogether one of those men who must write to the Times or go mad. Dost like the picture?

Both these men, who were walking together, looked at me rather hard; and I attributed the Dragon's failure to stop at the Sign of the Rose to the silly vanity which forbade his wearing "specs" like a sensible old gentleman. Accordingly, with laudable presence of mind, I did what seemed the only thing to do.

I stepped forward, and addressed him with the modest firmness Madame de Maluet's pupils are taught in "deportment lessons." "I beg your pardon, but aren't you Sir Lionel Pendragon?"

"I am Lionel Pendragon," said the other man—the quite young man.

Mother, you could have knocked me down with the shadow of a moth-eaten feather!

They both took off their travelling caps. The real Dragon's was in decent taste. The Mock Dragon's displayed an offensive chess-board check.

"Have you come to say—that Miss Lethbridge has been prevented from meeting me?" asked the real one—the R. D., I'll call him for the moment.

"I am——" It stuck in my throat and wouldn't go up or down, so I compromised—which was weak of me, as I always think on principle you'd better lie all in all or not at all. "I suppose you don't recognize me?" I mumbled fluffily.

"What—it's not possible that you're Ellaline Lethbridge!" the R. D. exclaimed, in surprise, which might mean horror of my person or a compliment.

I gasped like a fish out of water, and wriggled my neck in a silly way, which a charitable man, unaccustomed to women, might take for schoolgirl gawkishness in a spasm of acquiescence.

Instantly he put out his hand and wrung mine extremely hard. It would have crunched the real Ellaline's rings into her poor little fingers.

"You must forgive me," he said. "I saw the rose"—and he smiled a wonderfully agreeable, undragonlike smile, which put him back to thirty-two—"but I was looking out for a very different sort of—er—young lady."

"Why?" I asked, losing my presence of mind.

"I—well, really, I don't know why," said he.

"And I was looking for a very different sort of man," I retorted, feeling idiotically schoolgirlish, and sillier every minute.

He smiled again then, even more nicely than before, and followed the example I had set. "Why?" he inquired.

Unlike him, I did know why only too well. But it was difficult to explain. Still, I had to say something or make things worse. "When in doubt play a trump, or tell the truth," I quoted to myself as a precept; and said out aloud that, somehow or other, I'd thought he would be old.

"So I am old," he said, "old enough to be your father." When he added that information, he looked as if he would have liked to take it back again, and his face coloured up with a dull, painful red, as if he'd said something attached to a disagreeable memory. That was what his expression suggested to me; but as I know for a fact that he has not at all a nice, kind character, I suppose in reality what he felt was only a stupid prick of vanity at having inadvertently given his age away. I nearly blurted out the truth about mine, which would have got me into hot water at once, as Ellaline's hardly nineteen and I'm practically twenty-one—worse luck for you.

By this time the Mock Dragon had walked slowly on, but the brown image in "native" dress had glued himself to the platform near by, too respectful to be aware of my existence. While I was debating whether or no the last speech called for an answer, the R. D. had a sudden thought which gave him an excuse to change the subject.

"Where's your chaperon?" he snapped, with a flash of the eye, which was his first betrayal of the hidden devil within him.

"She was called away to visit a relative," I answered, promptly; because Ellaline and I had agreed I was to say that; and in a way it was true.

"You didn't come here alone?" said he.

"I had to," said I.

"Then it's a monstrous thing that Madame de Maluet should have let you," he growled. "I shall write and tell her so."

"Oh, don't, please don't," I begged, you can guess how anxiously. "She really couldn't help it, and I shall be so sorry to distress her." He was still glaring, and desperation made me crafty. "You wouldn't refuse the first thing I've asked you?" I tried to wheedle him.

I hoped—for Ellaline's sake, of course—that I should get another smile; but instead, I got a frown.

"Now I begin to realize that you are—your mother's daughter," said he, in a queer, hard tone. "No, I won't refuse the first thing you ask me. But perhaps you'd better not consider that a precedent."

"I won't," said I. He'd been looking so pleased with me before, as if he'd found me in a prize package, or won me in a lottery when he'd expected to draw a blank; but though he gave in without a struggle to my wheedling, he now looked as if he'd discovered that I was stuffed with sawdust. My quick, "I won't," didn't seem to encourage him a bit.

"Well," he said, in a duller tone, "we'll get out of this. It was very kind of you to come and meet me. I see now I oughtn't to have asked it; but to tell the truth, the thought of going to a girls' school, and claiming you——"

"I quite understand," I nipped in. "This is much better. My luggage is all here," I added. "I couldn't think where else to send it, as I didn't know what your plans might be."

At that he looked annoyed again, but luckily, only with himself this time. "I fear I am an ass where women's affairs are concerned," he said. "Of course I ought to have thought about your luggage, and settled every detail for you with Madame de Maluet, instead of trusting to her discretion. Still, it does seem as if she——"

I wouldn't let him blame Madame; but I couldn't defend her without risking danger for Ellaline and myself, because Madame's arrangements were all perfect, if we hadn't secretly upset them. "I have so little luggage," I broke in, trying to make up with emphasis for irrelevancy. "And Madame considers me quite a grown-up person, I assure you."

"I suppose you are," he admitted, observing my inches with a worried air. "I ought to have realized; but somehow or other I expected to find a child."

"I shall be less bother to you than if I were a child," I consoled him.

This did make him smile again, for some reason, as he replied that he wasn't sure. And we were starting to hook ourselves on to the tail end of the dwindling procession, quite on friendly terms, when to my horror that young English cadlet—or boundling, which you will—strolled calmly out in front of us, and said, "How do you do, Sir Lionel Pendragon? I'm afraid you don't remember me. Dick Burden. Anyhow, you'll recollect my mother and aunt."

I had forgotten all about the creature, dearest; but there he had been lurking, ready to pounce. And what bad luck that he should know Ellaline's guardian, wasn't it?

At first I thought maybe he really had had business at the Gare de Lyon, and that I'd partly misjudged him. And then it flashed into my head that, on the contrary, he didn't really know Sir Lionel, but had overheard the name, and was doing a "bluff" to get introduced to me. Wasn't that a conceited idea? But neither was true. At least the latter wasn't, I know, and I'm pretty sure the first wasn't. What I think, is this: that he simply followed me to the Gare de Lyon for the "deviltry" of the thing, and because he'd nothing better to do. That he hung about in sheer curiosity, to see whom I was meeting; and that he recognized the Dragon as an old acquaintance. I once fondly supposed coincidences were remarkable and rare events, but I've known ever since I've known the troubles of life that it's only agreeable ones which are rare, such as coming across your long-lost millionaire-uncle who's decided to leave you all his money, just as you'd made up your mind to commit suicide or marry a Jewish diamond merchant. Disagreeable coincidences sit about on damp clouds ready to fall on you the minute they think you don't expect them, and they're more likely to occur than not. That's my experience. Evidently the Dragon did remember Dick's mother and aunt, for the first blankness of his expression brightened into intelligence with the mention of the youth's female belongings. He held out his hand cordially, and remarked that of course he remembered Mrs. Burden and Mrs. Senter. As for Dick, he had grown out of all recollection.

"It was a good many years ago," returned the said Dick, hastening to disprove the slur of youthfulness. "It was just before I went to Sandhurst. But you haven't changed. I knew you at once."

"On leave, I suppose?" suggested Sir Lionel.

"No," said Dick, "I'm not in the army. Failed. Truth is, I didn't want to get in. Wasn't cut out for it. There's only one profession I care for."

"What's that?" the Dragon was obliged to ask, out of politeness, though I don't think he cared much.

"The fact is," returned Mr. Burden (a most appropriate name, according to my point of view), "it's rather a queer one, or might seem so to you, and I've promised the mater I won't talk of it unless I do adopt it. And I'm over here qualifying, now."

It was easy to see that he hoped he'd excited our curiosity; and he must have been disappointed in Sir Lionel's half-hearted "Indeed?" As for me, I tried to make my eyes look like boiled gooseberries, an unenthusiastic fruit, especially when cooked. I was delighted with the Dragon, though, for not introducing him.

Having said "indeed," Sir Lionel added that we must be getting on—luggage to see to; his valet a foreigner, and more bother than use. I took my cue, and pattered along by my guardian's side, his tall form a narrow yet impassable bulwark between me and Mr. Dick Burden. But Mr. D. B. pattered too, refusing to be thrown off.

He asked Sir Lionel if he were staying on in Paris; and in the short conversation that followed I picked up morsels of news which hadn't been given me yet. It appeared that the Dragon's sister (who would suspect a dragon of sisters?) had wired to Marseilles that she would meet him in Paris, and he "expected to find her at an hotel." He didn't say what hotel, so it was evident Mr. Dick Burden need not hope for an invitation to call. Apparently our plans depended somewhat on her, but Sir Lionel "thought we should get away next day at latest." There was nothing to keep him in Paris, and he was in a hurry to reach England. I was glad to hear that, for fear some more coincidences might happen, such as meeting Madame de Maluet or one of the teachers holiday-making. Conscience does make you a coward! I never noticed mine much before. I wish you could take anti-conscience powders, as you do for neuralgia. Wouldn't they sell like hot cakes?

At last Mr. Dick Burden had to go away without getting the introduction he wanted, and Sir Lionel was either very absent-minded or else very obstinate not to give it, I'm not sure which; but if I were a betting character I should bet on the latter. I begin to see that his dragon-ness may be expected to leak out in his attitude toward Woman as a Sex. Already I've detected the most primitive, almost primæval, ideas in him, which probably he contracted in Bengal. Would you believe it, he insisted on my putting on a veil to travel with?—but I haven't come to that part yet.

As for Mr. Burden, as I said, he disappeared from our view; but I doubt if we disappeared from his. You may think this is conceited in me, but, as he took off his Panama in saying good-bye, he contrived to peer at me round an unfortified corner of the Dragon, and the look he flung me said more plainly than words: "This is all right, but I'm hanged if I don't see it through," or something even more emphatic to that effect.

Sir Lionel was surprised when he saw my luggage, which we picked up when he'd claimed his own.

"I thought young ladies never went anywhere without a dozen boxes," said he.

"Oh, mamma and I travelled half over Europe with only one trunk and two bags between us," I blurted out, before I stopped to think. Then I wished the floor would yawn and swallow me up.

He did stare!—and his eyes are dreadfully piercing when he stares. They are very nice-looking gray ones; but I can tell you they felt like hatpins.

"I should have thought you were too young in those days to know anything about luggage," said he.

That gave me a straw to clutch. "Madame de Maluet has told me a great deal." (So she has, about one thing or another; mostly my own faults.)

"Oh, I see," he said. It must have seemed funny to him, my saying that about the trunks, as Ellaline's mother died when E. was four.

He hadn't much luggage, either; no golf clubs, or battle-axes, or whatever you play about with in Bengal when you aren't terrorizing the natives. He sent the brown servant off in one cab with our things, and put me in another, into which he also mounted. It did seem funny driving off with him, for when I came to think of it, I was never alone with a man before; but he was gawkier about it than I was. Not exactly shy; I hardly know how to express it, but he couldn't help showing that he was out of his element.

Oh, I forgot to tell you, he'd shaken hands with the Mock Dragon, and shunted him off just as ruthlessly as he did the boy. "See you in London, sooner or later," said he. As if anyone could want to see such a disagreeable old thing! Yet, perhaps, if I but knew, the Mock Dragon's character may be the nobler of the two. If I were to judge by appearances, I should have liked the real Dragon's looks, and thought from first sight that he was rather a brave, fine, high-principled person, even unselfish. Whereas I know from all Ellaline has told me that his qualities are quite the reverse of these.

We were going to the Grand Hotel, and driving there he pumped up a few perfunctory sort of questions about school, the way grown-up people who don't understand children talk to little girls. You know: "Do you like your lessons? What do you do on holidays? What is your middle name?" sort of thing. I was afraid I should laugh, so I asked him questions instead; and all the time he seemed to be studying me in a puzzled, surprised way, as if I were a duck that had just stepped out of a chicken egg, or a goblin in a Nonconformist home. (If he keeps on doing this, I shall have to find out what he means by it, or burst.)

I asked him about his sister, as I thought Bengal might be a sore subject, and he appeared to think that I already knew something of her. If Ellaline does know, she forgot to tell me; and I hope other things like that won't be continually cropping up, or my nerves won't stand it. I shall take to throwing spoons and tea-cups.

He reminded me of her name being Mrs. Norton, and that she's a widow. He hadn't expected her to come over, he said, and he was surprised to get her telegram, but no doubt he'd find out that she'd a pretty good reason. And it was nothing to be astonished at, her not meeting him at the Gare de Lyon, for she invariably missed people when she went to railway stations. It had been a characteristic of hers since youth. When they were both young they were often in Paris together, for they had French cousins (Ellaline's mother's people, I suppose), and then they stopped at the Grand Hotel. He hadn't been there, though, he added, for nearly twenty years; and had been out of England, without coming back, for fifteen. That made him seem old, talking of what happened twenty years ago—almost my whole life. Yet he doesn't look more than thirty-five at most. I wonder does the climate of Bengal preserve people, like flies in amber? Perhaps he's really sixty, and has this unnatural appearance of youth.

"Does Mrs. Norton know about—me?" I asked.

"Why; of course she does," said he. "I wrote her she must come and live with me when I found I'd got to have——" He shut up like a clam, on that, and looked so horribly ashamed of himself that I burst out laughing.

"Please don't mind," said I. "I know I'm an incubus, but I'll try to be as little trouble as possible."

"You're not an incubus," he contradicted me, almost indignantly. "You're entirely different from what I thought you would be."

"Oh, then you thought I would be an incubus?" I couldn't resist the temptation of retorting. Maybe it was cruel, but there's no society for the prevention of cruelty to dragons, so it can't be considered wrong in humane circles.

"Not at all. But I—I don't know much about women, especially girls," said he. "And I told you I thought of you as a child."

"I hope you haven't gone to the trouble of engaging a nurse for me?" I suggested. And if he were cross at being teased, he didn't show it. He said he'd trusted all such arrangements to his sister. He hadn't seen her for many years, but she was good-natured, and he hoped that we would get on. What I principally hoped was that she wouldn't prove to be of a suspicious nature; for a detective on the hearth would be inconvenient, and women can be so sharp about each other! I've found that out at Madame de Maluet's; I never would from you, dear. You weren't a cat in any of your previous incarnations. I think you must have "evoluted" from that neat blending of serpent and dove which eventually produces a perfect Parisienne.

We went into the big hall of the Grand Hotel, where Sir Lionel said in "his day" carriages used to drive in; and suddenly, to my own surprise, I felt gay and excited, as if this were life, and I had begun to live. I didn't regret having to play Ellaline one bit. Everything seemed great fun. You know, darling, I haven't had much "life," except in you and books, since I was sixteen, and our pennies and jauntings finished up at the same time; though I had plenty before that—all sorts of "samples," anyhow. I suppose it must have been the bright, worldly look of the hotel which gave me that tingling sensation, as if a little wild bird had burst into song in my heart.

Although it's out of season for Parisians, the hall was full of fashionable-seeming people, mostly Americans and other foreigners. As we came in, a lady rose from a seat near the door. She was small, and the least fashionable or well-dressed person in the room, yet with the air of being satisfied with herself morally. I saw at once she was of the type who considers her church a "home from home"; who dresses her house as if it were a person, and upholsters herself as if she were a sofa. Of course, I knew it was Mrs. Norton, and I was disappointed. I would almost have preferred her to be catty.

She and her brother hadn't seen each other for fifteen years, but they met as calmly as if they had lunched together yesterday. I think, though, that was more her fault than his, for when he held out his hand she lifted it up on a level with her chin to shake; and of course that would have taken the "go" out of a grasshopper. I suppose it wouldn't have been "good form" to kiss in a hotel hall, but if I retrieved a long-lost brother in any sort of hall, I don't believe I could resist.

Her hair was so plainly drawn back, it was like a moral influence, and her toque sat up high on her head like a bun or a travelling pincushion. The only trimming on her dress was buttons, but there were a large family of them.

Sir Lionel introduced us, and she said she was pleased to meet me. Also, that I was not at all like my mother or father. Then she asked if I had ever been to England; but luckily, before I'd had a chance to compromise myself by saying that I'd lived a few months in London, but had been nowhere else (there's where our money began to give out), her brother reminded her that I was only four when I left England.

"Of course, I had forgotten," said Mrs. Norton. "But don't they ever take them over to see the British Museum or the National Gallery? I should have thought it would be an education—with cheap returns."

"Probably French schoolmistresses believe that their pupils get their money's worth on the French side of the Channel," replied Sir Lionel.

"Oh!" said Mrs. Norton; and looked at me as if to see how the system had answered. I'm sure she approved of the gray serge and the sailor hat more than she approved of the girl in them. You see, I don't think she sanctions hair that isn't dark brown.

We didn't sit down, but talked standing up. Sir Lionel and his sister throwing me words out of politeness now and then. She has a nice voice, though cold as iced water that has been filtered. Her name is Emily. It would be!

He said he was surprised as well as pleased to get her telegram on arriving at Marseilles, and it was very good of her to come to Paris and meet him. She said not at all, it was no trouble, but a pleasure, or rather it would be, if it weren't for the sad reason that brought her.

"Why, is anybody dead?" asked Sir Lionel, looking as if he were running over a list in his head, but couldn't call up a name which concerned him personally.

"There's been a thinning off among old friends lately, I'm sorry to say; I've told you about most of them, I think, in postscripts," replied Mrs. Norton. "But it wasn't their loss, poor dears, which brought me over. It was the fire."

"What fire?" her brother wanted to know.

"Why, your fire. Surely you must have seen about it in to-day's London papers?"

"To-day's London papers won't get to Marseilles till to-morrow, and I haven't been long enough in Paris to see one yet," explained Sir Lionel. "Have I had a serious fire, and what has been burnt?" He spoke as coolly as if it were the question of a mutton chop.

"Part of the house," returned Mrs. Norton, not even trying to break it to him.

"I hope not the old part," said he.

"No, it is the new wing. But that seemed to me such a pity. Such a beautiful bathroom, hot and cold, spray and shower, quite destroyed; and a noble linen closet, heated throughout with pipes, and fully stocked."

"The bathroom may have been early Pullman, and the linen closet late German Lloyd, my dear Emily; but the rest of the house is Tudor, and can't be replaced," said Sir Lionel; and I was sure, as he looked down at his sister, of a thing I'd already suspected: that he has a sense of humour. That's a modern improvement with which you wouldn't expect a dragon to be fitted; but I begin to see that this is an elaborate and complicated Dragon. Some people are Pharisees about their sense of humour, and keep harping on it till you wish it were a live wire and would electrocute them. He would rather be ashamed of his, I fancy, and yet it must have amused him, and made him feel good chums with himself, away out in Bengal.

Mrs. Norton said that Warings had very handsome Tudor dining-rooms in one or two of their model houses, so nothing was irrevocable nowadays; but she was pleased, if he was, that only the modern wing was injured. It had happened yesterday morning, just too late for the newspapers, which must have annoyed the editors; and she had felt that it would be best to undertake the journey to Paris, and consult about plans, as it might make a difference (here she glanced at me); but she hadn't mentioned the fire when wiring, because things seemed worse in telegrams, and besides, it would have been a useless expense. No doubt it had been stupid of her, but she had fancied he would certainly see it in the paper, with all details, and therefore guess why she was meeting him.

"We have nowhere to take Miss Lethbridge," said she, "since Graylees Castle will be overrun with workmen for some time to come. I didn't know but you might feel it would be best, after all, for us to put her again in charge of her old schoolmistress for a few weeks."

If hair could really rise, mine would have instantly cast out every hairpin, as if they were so many evil spirits, and have stood out all around my head like Strumpelpeter's. Yet there was nothing I could say. If I were mistress of a dozen languages, I should have had to be speechless in every one. But I saw Sir Lionel looking at me, and I hastily gave him a silent treatment with my eyes. It had the most satisfactory effect.

"No, I don't think we will take her back to Madame de Maluet's," said he. "Madame may have made other plans for the holiday season. Perhaps she is going away."

"I'm sure she is," said I. "She is going to visit her mother-in-law's aunt."

Sir Lionel was still looking at me, lost in thought. (I forget if I mentioned that he has nice eyes? I haven't time to look back and see if I did, now. I'm scribbling as fast as I can. We shall soon land, and I want to post this at Dover, if I can get an English stamp "off" someone, as "Sissy" Williams, our only British neighbour, says.)

"How would you like a motor-car trip?" Sir Lionel asked abruptly.

The relief from suspense was almost too great, and I nearly jumped down his throat, so, after all, it would have been my own fault if the Dragon had eaten me. "I should adore it!" I said.

"My dear!" protested Mrs. Norton, indulgently. "One adores Heavenly Beings."

"I'm not sure a motor-car isn't a heavenly being," said I, "though perhaps without capitals."

The Dragon smiled, but she looked awfully shocked, and no doubt blamed Madame de Maluet.

"I've a forty-horse Mercédès promised to be ready on my arrival," said Sir Lionel, still reflective. "You know, Emily, the little twelve-horse-power car I had sent out to East Bengal was a Mercédès. If I could drive her, I can drive a bigger car. Everybody says it's easier. And young Nick has learned to be a first-rate mechanic."

I suppose young Nick must be the Dragon's pet name for the bronze image. What fun that he should be a chauffeur! Fancy an Indian Idol squatted on the front seat of an up-to-date automobile. But when you come to think of it, there have been other gods in cars. I only hope, if I'm to be behind him, this one won't behave like Juggernaut. He wears almost too many clothes, for he is the type that would look over-dressed in a bangle.

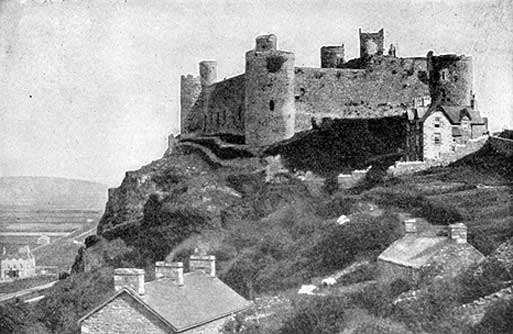

"We might have an eight or ten weeks' run about England," the Dragon went on, "while things are being made straight at Graylees. It would be good to see something of the blessed old island again before settling down."

"One would think you were quite pleased at the fire, Lionel," remarked his sister, who evidently believes it wrong to look on the bright side of things, and right to expect the worst—like an undertaker calling for a client before he's dead.

"What is, is," returned he. "We may as well make the best of it. You wouldn't mind a motor tour, would you, Emily?"

"I would go if it were my duty, and you desired it," she said, looking as if she ought to be on stained glass, with half a halo, "only I am hardly young enough to consider motoring as a pleasure."

"There aren't many years between us," replied her brother, too polite to say whether he were in front or behind, "but I confess I do regard it as a pleasure."

"A man is different," she admitted.

Thank goodness, he is!

Then they talked more about the fire, which, it seems, happened through something being wrong with a flue, in a room where Mrs. N. had told a servant to build a fire on account of dampness. It must be a wonderful old place from what they both let drop. (I told you in another letter how Sir Lionel had inherited it, about the same time as his title, or a little later. The estate, though, comes from the mother's side, and her people were from Warwickshire.) His cool British way of saying and taking things is a good deal on the surface, I think. He would have hated us to see it, but I'm sure he worked himself up to quite a pitch of joyful excitement over the idea of the motor trip, as it developed in his mind. And it is splendid, isn't it, darling?

You know how sorry you were we hadn't been more economical, and made our money last long enough to travel in England, instead of having to stop short after a splash in London. Now I'm going to see bits in spite of all, until I'm "called away," and I'll try my best, in letters, to make you see what I do. Ellaline wouldn't have enjoyed such a tour, for she hates the country, or any place where it isn't suitable to wear high heels and picture hats. But I—oh, I! Twenty dragons on the same seat of the car with me couldn't prevent my revelling in it—though it may be cut short for me at any minute. As for Mrs. Norton——

But the stewardess has just said we shall be in, in five minutes. I had to come down to the ladies' cabin with Mrs. N. Now I haven't time to tell you any more, except that they both (Sir L. and his sister, I mean) wanted to get to England as soon as possible. I know she was disappointed not to fling her brother's ward back to Madame de Maluet, and probably wouldn't have come over to Paris if she hadn't hoped to bring it off; but she resigns herself to things easily when a man says they're best. It was Sir Lionel who wanted particularly to cross to-night, though he didn't urge it; but she said, "Very well, dear. I think you're right."

So here we are. A large bell is ringing, and so is my heart. I mean it's beating. Good-bye, dearest. I'll write again to-morrow—or rather to-day, for it's a lovely sunrise, like a good omen—when we get settled somewhere. I believe we're going to a London hotel. Yes, stewardess. Oh, I ought to have said that to her, instead of writing it to you. She interrupted.

Love—love.

Your Audrie, Their Ellaline.

V

AUDRIE BRENDON TO HER MOTHER

Ritz Hotel, London,

July 8th

Angel: May your wings never moult! I hope you didn't think me extravagant wiring yesterday, instead of writing. I was too busy baking the yeasty dough of my impressions to write a letter worth reading; and when one has practically no money, what's the good of being economical? You know the sole point of sympathy I ever touched with "Sissy" Williams was his famous speech: "If I can't earn five hundred a year, it's not worth while worrying to earn anything"; which excused his settling down as a "remittance man," in the top flat, at forty francs a month.

Dearest, the Dragon hasn't drag-ged once, yet! And, by the way, till he does so, I think I won't call him Dragon again. It's rather gratuitous, as I'm eating his bread—or rather, his perfectly gorgeous à la cartes, and am literally smeared with luxury, from my rising up until my lying down, at his expense.

I know, and you know, because I repeated it word for word, that Ellaline said she thought he must have been well paid for undertaking to "guardian" her, as his hard, selfish type does nothing for nothing; and she has always seemed so very rich (quite the heiress of the school, envied for her dresses and privileges) that there might be temptations for an unscrupulous man to pick up a few plums here and there. But—well, of course Ellaline ought to know, after being his ward ever since she was four, and hearing things on the best authority about the horrid way he treated her mother, as well as suffering from his cruel heartlessness all these years. Never a letter written to herself; never the least little present; never a wish to hear from her, or see her photograph; all business carried on between himself and Madame de Maluet, who is too discreet to prejudice a ward against a guardian. And I—I saw him only day before yesterday for the first time. What can I know about him? I've no experience in reading characters of men. The dear old Abbé and a few masters in the school are the only ones I have a bowing acquaintance with—except "Sissy" Williams, who doesn't count. It's dangerous to trust to one's instincts, no doubt, for it's so difficult to be sure a wish isn't disguising itself as instinct, in rouge and a golden wig.

But then, there's the man's profile, which is of the knight-of-old, Crusader pattern, a regular hook to hang respect upon, though I'd be doing it injustice if I let you imagine it's shaped like a hook. It isn't; it's quite beautiful; and you find yourself furtively, semi-consciously sketching it in air with your forefinger as you look at it. It suggests race, and noblesse oblige, and a long line of soldier ancestors, and that sort of thing, such as you used to say survived visibly among the English aristocracy and English peasantry (not in the mixed-up middle classes) more markedly than anywhere else. That must mean some correspondence in character, mustn't it? Or can it be a mask, handed down by noble ancestry to cover up moral defects in a degenerate descendant?

Am I gabbling school-girl gush, or am I groping toward light? You know what I want to say, anyhow. The impression Sir Lionel Pendragon makes on me would be different if he hadn't been described by Ellaline. I should have supposed him quite easy to read, if he'd happened upon me, unheralded—as a big ship looms over a little bark, on the high sea. I'd have thought him a simple enough, straightforward character in that case. I should have put him in the class with his own Tudor castle—not that I've ever yet seen a Tudor castle, except in photographs or on postcards. But I'd have said to myself: If he'd been born a house instead of a man, he'd have been built centuries and centuries ago, by strong barons who knew exactly what they wanted, and grabbed it. He'd have been a castle, an early Tudor castle, battlemented and surrounded by a moat, fortified, of course, and impregnable to the enemy, unless they treacherously blew him up. He would have had several secret rooms, but they would contain chests of treasure, not nasty skeletons.

Now you understand exactly what I'd be thinking of the alleged Dragon, if it weren't for Ellaline. But as it is, I don't know what to think of him. That's why I describe him as elaborate and complicated, because, I suppose, he must be totally different inside from what he seems outside.

Anyhow, I don't care—it's lovely being at the Ritz. And we're in the newspapers this morning, Emily and I shining by reflected light; mine doubly reflected, like the earth's light shining on to the moon, and from that being passed on to something else—some poor little chipped meteorite strayed out of the Milky Way.

It was Mrs. Norton who discovered the article about Sir Lionel—half a column—in the Morning Post and she sent out for lots of other papers without saying anything to her brother, for—according to her—he "hates that sort of thing."

I didn't have time to tell you in my last that she was sick crossing the Channel (though it was as smooth as if it had been ironed, and only a few wrinkles left in), but apparently she considers it good form for a female to be slightly ill in a ladylike way on boats; so, of course, she is. And as I was decent to her, she decided to like me better than she thought she would at first. For some reason they both seemed prejudiced against me (I mean against Ellaline) to begin with. I can't think why; and slowly, with unconcealable surprise, they are changing their minds. Changing one's mind keeps one's soul nice and clean and fresh; so theirs will be well aired, owing to me.

Emily has become quite resigned to my existence, and doles me out small confidences. She has not a rich nature, to begin with, and it has never been fertilized much, so it's rather sterile; but no noxious weeds, anyhow, as there may be in Sir Lionel's more generous and cultivated soil. I think I shall get on with her pretty well after all, especially motoring, when I can take her with plenty of ozone. She is a little afraid of her brother, though he's five years younger than she (I've now learned), but extremely proud of him; and it was quite pathetic, her cutting out the stuff about him in the papers, this morning, and showing every bit to me, before pasting all in a book she has been keeping for years, entirely concerned with Sir Lionel. She says she will show that to me, too, some day, but I mustn't tell him. As if I would!

But about the newspapers. She didn't order any Radical ones, because she said they were always down on the aristocracy, and unjust as well as stupid; but she got one by mistake, and you've no idea how delighted the poor little woman was when it praised her brother up to the skies. Then she said there were some decent Radicals, after all.

Of course, one knows the difference between "Mirabeau judged by his friends and Mirabeau judged by the people," and can make allowances (if one's digestion's good) for points of view. But there's one thing certain, whether he's angel or devil, or something hybrid between the two, Sir Lionel Pendragon is a man of importance in the Public Eye. I wonder if Ellaline realizes his importance in that way? I can't think she does, or she would have mentioned it, as it needn't have interfered with her opinion of his private character.